B1

Mixed-Method Review of Strategies for Engaging with and Training Community-Based Partners to Improve the Outcomes of At-Risk Populations

This appendix provides a detailed description of the methods for and the evidence from the mixed-method review examining strategies for engaging with and training community-based partners (CBPs) to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations, which is summarized in Chapter 4.1

KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

The overarching question that guided this review addresses the effectiveness of different strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations after public health emergencies. Engaging with CBPs to meet the needs of at-risk populations may take place in the preparedness, response, and recovery phases of the emergency cycle. Recovery practices were outside the committee’s scope of work, but separate key review sub-questions were formulated for the preparedness and response phases. The committee also posed sub-questions related to documented benefits and harms of CBP engagement and training strategies and the factors that create barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of such strategies (see Box B1-1).

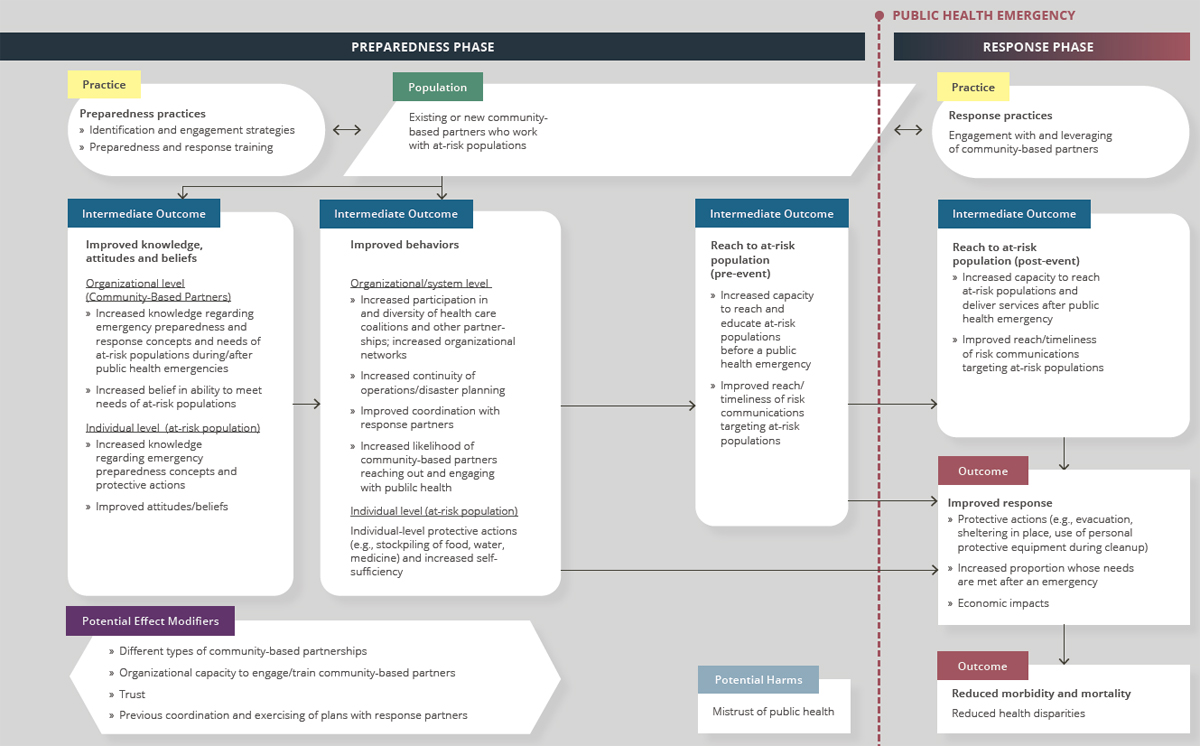

The theory behind this public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) practice is that when public health agencies adequately engage with and train CBPs who have established relationships with and/or serve at-risk populations on preparedness and response knowledge and concepts, the result is an increased capacity to reach at-risk populations before and during a public health emergency and the potential to reduce disaster-associated morbidity and mortality and ameliorate health disparities for those populations.

___________________

1 This appendix draws heavily on three reports commissioned by the committee: (1) “Data Extraction and Quality Assessment: Methodology and Evidence Tables” by the Brown University Center for Evidence Synthesis in Health; “Engaging with and Training Community-Based Partners for Public Health Emergencies: Qualitative Research Evidence Synthesis” by Julie Novak and Pradeep Sopory; and “Engaging with and Training Community-Based Partners to Improve the Outcomes of At-Risk Populations After Public Health Emergencies: Findings from Case Reports” by Sneha Patel (see Appendix C).

Engaging with and training CBPs may improve the outcomes of at-risk populations following a public health emergency through a number of presumed pathways (see the analytic framework in Figure B1-1). Such pathways generally focus on ensuring at-risk individuals’ postdisaster access to critical services and/or resources (e.g., food, medication, information). CBP intermediaries may provide such services and resources directly or may assist public health agencies (or other emergency responders) in reaching at-risk populations to deliver these services and resources before or after an emergency. CBPs also can be well positioned to help ensure the cultural appropriateness of preparedness and response materials, services, and training so that they are functionally accessible (e.g., available in different languages for non-English-speaking individuals) and likely to be well received.

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION

This section summarizes the evidence from the mixed-method review examining strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations. It begins with a description of the results of the literature search and then summarizes the evidence of effectiveness. In formulating its practice recommendation, the committee considered evidence beyond effectiveness, which was compiled using an Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework encompassing balance of benefits and harms, acceptability and preferences, feasibility and PHEPR system considerations, resource and economic considerations, equity, and ethical considerations. The evidence from each methodological stream applicable to each of the EtD criteria is discussed; a synthesis is provided in Table B1-10 later in this appendix and in Chapter 4. Graded finding statements from evidence syntheses are italicized in the narrative below.

Full details about the study eligibility criteria, search strategy, and processes for data extraction and individual study quality assessment are available in Appendix A. Appendix C links to all of the commissioned analyses informing this review.

NOTES: Arrows in the framework indicate hypothesized causal pathways between interventions and outcomes. Double-headed arrows indicate feedbac loops.

Results of the Literature Search

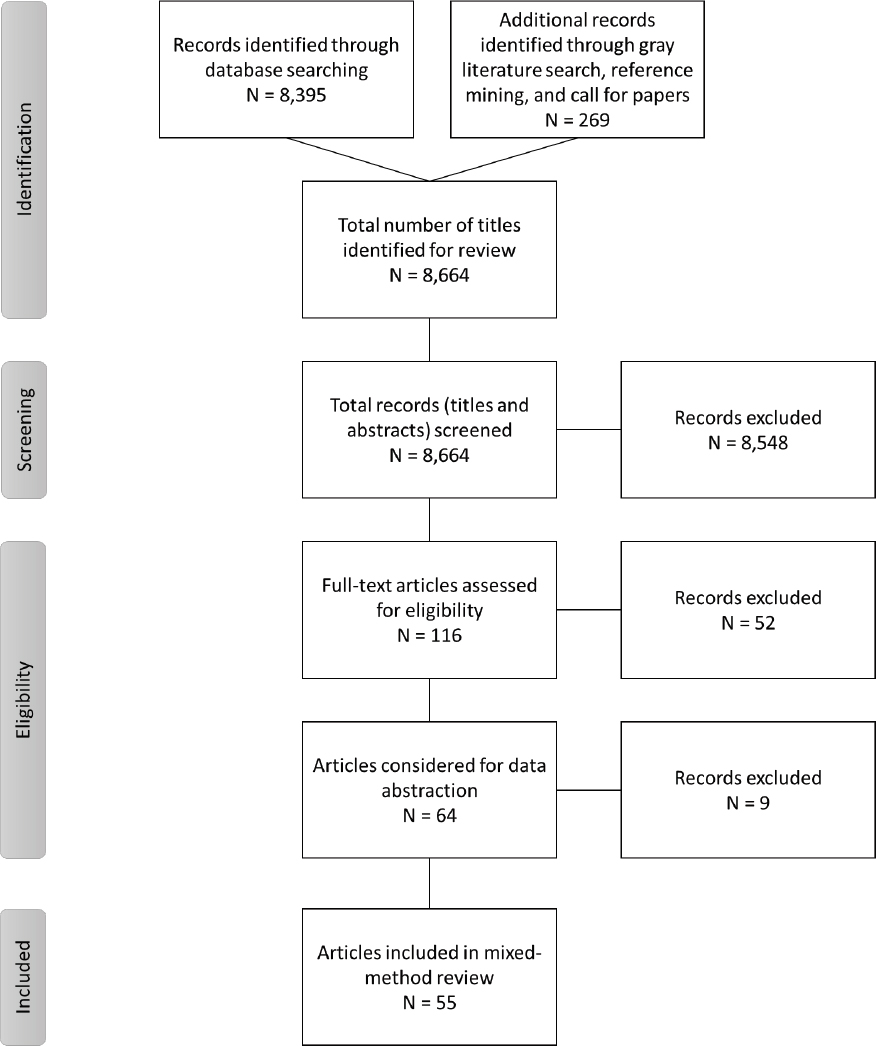

The searches of bibliographic databases identified a total of 8,395 potentially relevant citations (deduplicated) for the mixed-method review of strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations. A search of the gray literature, reference mining, and a call for reports contributed an additional 269 articles. All 8,664 citations were imported into EndNote and were included in title and abstract screening. During screening, 8,548 articles were excluded because their abstracts did not appear to answer any of the key questions or they indicated that the articles were commentaries, editorials, or opinion pieces. After the abstracts had been reviewed, 116 full-text articles were reviewed and assessed for eligibility for inclusion in the mixed-method review. The committee considered 64 articles for data extraction and ultimately included 55 articles in the mixed-method review. Figure B1-2 depicts the literature flow, indicating the number of articles included and excluded at each screening stage. Table B1-1 indicates the types of evidence included in this review.

A separate targeted search was conducted to identify relevant systematic reviews of the effectiveness of community engagement strategies and cultural tailoring of interventions from outside the PHEPR context. This search was conducted in Google Scholar, PubMed, the Office of Minority Health Knowledge Center, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Think Cultural Health Resource Library. This parallel evidence (as described in Chapter 3) was considered in determining the certainty of the evidence (COE) for strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations. The search was limited to systematic reviews published in the past 5 years (2015–2019). Reviews of interventions implemented only in low- and middle-income countries were excluded. Search terms included systematic, meta-analysis, community engagement, community partner, vulnerable, minority, marginalized, indigenous groups, disabilities, community intervention, intervention review, intervention evaluation, cultural tailoring, cultural targeting, community engagement, and cultural competency. Additionally, the seminal report Principles of Community Engagement (NIH et al., 2011) was reference mined. The targeted search yielded 13 systematic reviews that the committee considered.

1. Determining Evidence of Effect

Seven quantitative comparative and four quantitative noncomparative studies directly addressed the overarching key question regarding the effectiveness of different strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations after public health emergencies. All 11 studies examined strategies for engaging with or training CBPs before a public health emergency (preparedness phase). The committee found no quantitative research studies addressing the key question regarding the effectiveness of strategies for engaging with and leveraging existing CBPs during a public health emergency (response phase). Ten of these 11 studies evaluated strategies that involve both engaging and training CBPs.

Strategies identified by the committee in the body of evidence fall into two broad categories: (1) those aimed at training and/or engaging individual CBPs, with a goal of reaching particular at-risk populations (training programs may be targeted solely to CBPs or to both CBPs and members of the at-risk populations they serve); and (2) those aimed at engaging multiple CBPs in a coalition or other multistakeholder partnership. From these two categories, three strategies for training and/or engaging CBPs were identified and evaluated separately:

___________________

2 The committee uses the term “culturally tailored” to describe an intervention that is targeted and/or tailored to ensure that it meets the unique needs of the target group by incorporating their experiences and norms and values.

| Evidence Typea | Number of Studies (as applicable)b | |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative comparative | 7 | |

| Quantitative noncomparative (postintervention measure only)c | 4 | |

| Qualitative | 23 | |

| Modeling | 0 | |

| Descriptive surveys | 7 | |

| Case reports | 15d | |

| After action reports | N/A | |

| Mechanistic | N/A | |

| Parallel (systematic reviews)e | 13 | |

a Evidence types are defined in Chapter 3.

b Note that sibling articles (different results from the same study published in separate articles) are counted as one study in this table. Mixed-method studies may be counted in more than one category.

c Quantitative noncomparative studies were considered separately for the purpose of evaluating evidence of effect but were included in the case report evidence synthesis (or qualitative evidence synthesis in the case of mixed-method studies) to identify themes relevant to the Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework.

d A sample of case reports was prioritized for inclusion in this review based on relevance to the key questions, as described in Chapter 3.

e Parallel evidence for the purposes of this review was derived from existing systematic reviews of similar practices from outside the PHEPR context.

- implementation of culturally tailored preparedness2 training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve,

- engagement of CBPs in preparedness outreach activities targeting at-risk populations, and

- engagement and training of CBPs in coalitions addressing public health preparedness/ resilience.

A meta-analysis of the evidence for the effectiveness of these strategies was not feasible, so the committee conducted a synthesis without meta-analysis (as described in Chapter 3). Consistent with the methods described in Chapter 3, in making its final judgment on the evidence of effectiveness for strategies for engaging with and training CBPs to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations, the committee considered other types of evidence that could inform a determination of what works for whom and in which contexts, ultimately reaching consensus on the COE for each outcome. Including forms of evidence beyond quantitative comparative studies is particularly important when assessing evidence in settings where controlled studies are challenging to conduct and/or other forms of quantitative comparative data are difficult to obtain. As discussed in Chapter 3, descriptive evidence from real-world implementation of practices offers the potential to corroborate research findings or explain differences in outcomes in practice settings, even if it has lesser value for causal inference. Moreover, qualitative studies can complement quantitative studies by providing additional useful evidence to guide real-world decision making, because well-conducted qualitative studies produce deep and rich understandings of how interven-

tions are implemented, delivered, and experienced. Other forms of evidence considered for evaluation of effectiveness included quantitative data reported in case reports of real disasters or public health emergencies, and parallel evidence from systematic reviews on community engagement and cultural tailoring of interventions outside the PHEPR context. The parallel evidence was considered recognizing that the engagement and training of CBPs to better reach and improve outcomes for individuals with social vulnerabilities has much broader application in public health beyond the PHEPR context, and the committee believes this broader body of evidence may have some applicability to the PHEPR practices evaluated in this review.

Implementation of Culturally Tailored Preparedness Training Programs for CBPs and At-Risk Populations They Serve

Evidence from quantitative research studies

Five quantitative comparative studies examined the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve. Three of these studies employed a train-the-trainer approach whereby CBP representatives were trained in emergency preparedness concepts and skills and subsequently trained at-risk populations. Outcomes of interest reported by the authors include PHEPR knowledge of CBP representatives, attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives regarding their preparedness to meet needs of at-risk individuals, and CBP disaster planning. Additionally, for studies in which training programs also targeted at-risk populations, outcomes of interest include knowledge of trained at-risk populations regarding PHEPR and protective actions, attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations regarding their preparedness, and preparedness behaviors of at-risk populations.

A community-based randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Eisenman and colleagues (2009) evaluated the effect on household disaster preparedness of participation in a program with promotoras (community health workers), who, after being trained in disaster preparedness, held face-to-face discussions about disaster preparedness with low-income Latino participants in Los Angeles County, California (Platica group). The media control group received culturally tailored mailings with preparedness information. Among participants who did not have disaster preparedness plans at baseline, household preparedness had significantly increased in both groups 3 months after the intervention, but those in the Platica group (N = 87) were more likely to increase household preparedness as measured by having a communication plan (p = 0.002) and a supply of numerous specific household preparedness items, including food (p = 0.013) and water (p = 0.003), relative to those in the media control group (N = 100). However, there were some concerns about the potential for social desirability bias and the generalizability of the study. Overall, the study (and each outcome) was deemed to be of moderate methodological quality.

Eisenman and colleagues (2014) also evaluated a train-the-trainer emergency preparedness program that was developed for and in consultation with adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs). Clients (with IDDs) of a community-based organization (CBO) in Los Angeles, California, that serves adults with IDDs were trained as peer mentors. In an RCT, adults with IDDs who received the peer-mentored emergency preparedness training (N = 42) reported statistically significantly greater improvements in disaster preparedness behaviors (p = 0.003) and marginally better earthquake preparedness knowledge (p = 0.052) at 1-month follow-up relative to those in a waitlist (delayed intervention) control group (N = 40). Adults with IDDs in the experimental group increased preparedness activities by 19 percent and preparedness knowledge by 8 percent (as compared with 5 percent and 1 percent in the control group, respectively). The measures were not validated, and there

was some concern about social desirability bias. Overall, the study (and each outcome) was deemed to be of moderate methodological quality.

The Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services (2008) evaluated an intervention similar to that examined by Eisenman and colleagues (2009) using a prospective pre-post design (a single group study for which outcome data are available pre- and postintervention). After receiving training in emergency preparedness, six experienced Vías de la Salud health promoters conducted group educational sessions with Latino residents in Montgomery County, Maryland. Statistical analyses are not reported, but among the health promoters, knowledge improved from baseline immediately after their training and after the community education sessions regarding emergency plans, emergency shelters, evacuation, emergency preparation, and emergency supply kits. Except for knowledge about evacuation, promoters’ knowledge (N = 5–6) was stable (mostly at 100 percent correct) from immediately after training until after the community education sessions. Among community members who participated in the educational sessions (N = 29–39), compared with before the course, there were improvements in feelings regarding their preparedness (from 8 percent before the educational sessions to 69 percent after completing all three sessions) and in self-reported household preparedness practices (e.g., having an emergency plan and stockpiling emergency supplies). After the third educational session, 100 percent of participants reported having an emergency plan (as compared with 23 percent before the training), and stockpiling of food and water had been completed by 93 percent and 97 percent, respectively (as compared with 21 percent and 10 percent at baseline). There were concerns about the validity of the study’s outcomes. Overall, the study (and each outcome) was deemed to be of moderate methodological quality.

Hites and colleagues (2012) evaluated the effectiveness of a culturally tailored training program (for CBPs only) using a prospective pre-post study design. This program, adapted for community health representatives who serve tribal populations in the Navajo Nation (in Arizona), was shown to increase PHEPR-related knowledge as measured by scores for six Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–defined bioterrorism competencies. Compared with testing prior to training, the community health representatives (N = 83) scored statistically significantly better after the training on five of the six competencies, although the median number of correct answers rose by only one or two questions (out of one to seven questions per competency). The outcome was not validated, and overall, the study (and each outcome) was deemed to be of moderate methodological quality.

McCabe and colleagues (2014a,b) examined companion training interventions—implemented though a partnership comprising an academic health center, local health departments, and faith-based organizations (FBOs)—aimed at improving mental health preparedness and community resilience. The authors used a prospective pre-post design to assess the outcomes of sequential 1-day workshops in psychological first aid (PFA) and guided preparedness planning (GPP). FBO partners recruited members of their congregation and local communities (rural and urban) to receive PFA training, and subsequently designated small teams to represent their FBO in GPP and to develop draft disaster plans for their organization and community. Statistically significant improvements were observed after the training in objectively measured knowledge, as well as self-reported knowledge, skills, and some measures of attitudes (e.g., perceived self-efficacy, willingness to deliver PFA during an emergency) for PFA and GPP trainees (including at-risk rural cohorts). On average, approximately 80 percent of teams representing their FBO submitted a same-day draft of disaster plans following GPP, with average completeness scores ranging from 83.5 to 98.7 (out of 100).

At 1-year follow up, greater than 80 percent of respondent trainees were willing and confident in their ability to provide PFA following a disaster or public health emergency,

and approximately 20 percent had provided PFA at least once following a disaster or other public health emergency (nearly two-thirds had provided it to someone experiencing a personal crisis). Because FBO representatives and community members were trained together (approximately 70 percent of participants were community members) and outcomes were not measured separately for these different populations, the study findings could not be applied to the outcomes related to knowledge and attitudes and beliefs for CBP representatives. With the trained FBO representatives themselves considered to be members of the at-risk population (residents of rural areas), the study was deemed to be applicable to at-risk population outcomes (knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, behavior). For the GPP component of the intervention, trained teams were selected by FBOs to generate disaster plans for their organization. Consequently, the committee also deemed the study results applicable to the CBP disaster planning outcome. There were concerns about measures that were not validated and about self-reporting for some outcomes. Methodological quality was moderate for the outcomes of objectively measured knowledge and completion of disaster plans and poor for all other outcomes.

In addition to the quantitative comparative studies described above, four cross-sectional studies (postintervention measurements only) addressed questions related to the effectiveness of culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve. In a pilot of the earlier-described PFA training program implemented by McCabe and colleagues (2014a,b), the study team used a train-the-trainer model to provide culturally tailored PFA training to clergy members from urban areas in Maryland with large African American and Latino populations (McCabe et al., 2008). Self-reported self-efficacy with PFA among clergy following the training was high, ranging from 77.1 to 91.5 percent, depending on the evaluation item (e.g., accessing psychosocial and psychiatric resources, recognizing signs and symptoms of stress and acute stress disorder).

In a subsequent iteration of the culturally tailored PFA training program, the study team evaluated PFA training in a mixed cohort of FBO representatives and community residents from four rural counties in Maryland (McCabe et al., 2011). Following the training, 97–99 percent of trainees agreed or strongly agreed that training objectives related to acquisition of knowledge about the principles and practices of disaster mental health, PFA, at-risk populations, and self-care had been met. Additionally, 93–98 percent of trainees agreed or strongly agreed that their perceived self-efficacy for applying PFA techniques in a real-world disaster setting had improved. Immediately following the workshop, 31.5 percent of trainees submitted applications to be members of the Maryland Medical Professional Volunteer Corp, indicating a willingness to respond as a PFA provider.

McCabe and colleagues (2013) also trained FBO representatives and community members from the same rural Maryland counties in GPP. Following the training, 93–98 percent of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the program objectives had been met, core planning concepts had been learned, and the course had been a valuable experience. Depending on the evaluation item, 90–100 percent of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they had a better understanding of knowledge and skills required to create a disaster mental health plan following the training. Ninety-five percent of individual participants reported enhanced confidence (perceived self-efficacy) in their ability to execute disaster planning strategies and techniques (McCabe et al., 2013). All participants were able to generate partial disaster plan drafts by the end of the training, and by the end of the project, 15 out of 100 FBOs (all from a single county) had submitted completed disaster plans on behalf of their organizations and communities.

Laborde and colleagues (2013) similarly describe the results of a cross-sectional study evaluating a pilot disaster mental health training program, which was implemented as a

train-the-trainer program tailored to black community leaders and clinical providers in rural and coastal areas of North Carolina with high poverty levels. The mean posttest knowledge score for CBO leaders was 61 percent, and individual competency scores ranged from 42 to 82 percent (pretest scores were not measured).

Other evidence that may inform effectiveness

As noted earlier, in addition to the above direct evidence on tailored strategies for engaging with and training CBPs, the committee considered parallel evidence consisting of systematic reviews of community engagement and culturally tailored interventions used outside the PHEPR context to improve the outcomes of at-risk or disadvantaged populations (primarily populations of low socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic minorities).

The search for relevant systematic reviews yielded four broad reviews (all from the health field but not specific to a single population or health condition)—three on community engagement models (Cyril et al., 2015; O’Mara-Eves et al., 2015; Viswanathan et al., 2004) and one on cultural competence and tailoring of health care interventions (Butler et al., 2016). There was minimal overlap in primary studies across these four systematic reviews. Taken together, the systematic reviews provide promising evidence of a beneficial effect of community engagement and cultural tailoring on the outcomes that were evaluated, including knowledge of health risks and mitigation strategies, health behaviors (e.g., physical activity, healthy eating, smoking cessation, cancer screening), and health-related outcomes (e.g., hypertension, mental health conditions). The outcomes from the systematic reviews related to knowledge of health risks and health behaviors align reasonably with the outcomes related to PHEPR knowledge of trained populations and preparedness behaviors in the present review. Despite the beneficial effects described in the systematic reviews, however, authors of two of the four broad reviews—one on community engagement (Viswanathan et al., 2004) and one on culturally tailored interventions (Butler et al., 2016)—concluded that they could not determine the effectiveness of these broad classes of interventions, in part because of the heterogeneity of the included studies and the challenges of attributing the observed effects to one component of what is usually a multicomponent intervention.

In addition to the four broad systematic reviews, the committee’s search captured nine population- and health condition–specific systematic reviews of culturally tailored interventions targeting at-risk populations—many of which were educational—that were published after those broader reviews (DeRose and Rodriguez, 2019; Florez et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2016; McCall et al., 2019; McCallum et al., 2017; McCurley et al., 2017; Nasir et al., 2016; Schroeder et al., 2018; Shommu et al., 2016). All but one of these nine reviews (McCall et al., 2019) involve engagement of CBOs, FBOs, or community health workers. Overall, the more specific systematic reviews focus on adult populations of low socioeconomic status and/or racial and ethnic minorities. The majority address community-based participatory research intervention models utilizing cultural tailoring and community partnership methodology. Relevant outcomes discussed in these nine systemic reviews include knowledge of health risks (DeRose and Rodriguez, 2019; Kim et al., 2016; McCallum et al., 2017; Nasir et al., 2016; Shommu et al., 2016), health behavior (DeRose and Rodriguez, 2019; Florez et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2016; McCurley et al., 2017; Shommu et al., 2016), and health conditions (DeRose and Rodriguez, 2019; Florez et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2016; McCall et al., 2019; McCallum et al., 2017; McCurley et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2018; Shommu et al., 2016). All of the reviews report beneficial effects for at least some outcome measures. The authors of the reviews generally offer conclusions similar to those of the four broader systematic reviews described above: that community engagement and cultural tailoring are promising intervention methods, but that further rigorous study—including more RCTs, better

measurement of health outcomes and effect sizes, and more consistent study populations to reduce bias—is needed to provide higher-quality evidence with which to compare and contrast engagement methods.

One challenge when looking at these systematic reviews as parallel evidence on strategies for engaging with and training CBPs in PHEPR stems from the breadth of community engagement strategies covered in the reviews, not all of which involve CBPs as the committee has defined them. For example, some engagement strategies involve assembling a community advisory board comprising individual community members, which may not be comparable to a model whereby CBPs are engaged in co-designing and co-delivering interventions. Moreover, the authors of the reviews could not always distinguish the contribution of CBP engagement to the intervention effects. Additionally, the committee recognized that the motivation of at-risk populations to improve knowledge and behavior related to known health risks (e.g., diabetes, obesity) may not reflect their motivation to address risks from low-probability public health emergencies. As a result, the committee considered parallel evidence to be supportive3 rather than very supportive.

Summary of the evidence: PHEPR knowledge of CBP representatives

The committee concluded that there is low COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve improve PHEPR knowledge of CBP representatives. Two of the five quantitative comparative studies (Hites et al., 2012; Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008) and one of the four cross-sectional (postintervention) studies (Laborde et al., 2013) provide low COE regarding the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs on PHEPR knowledge of trained CBP representatives (see Table B1-2). Despite supportive parallel evidence (described above) and the absence of studies with discordant results, the weight of the evidence was insufficient to upgrade the COE.

___________________

3 As described in Chapter 3, the committee reviewed other evidence that informed the COE (e.g., mechanistic evidence, experiential evidence from case reports and after action reports, qualitative evidence) for coherence with the findings from the quantitative research studies and classified that evidence as very supportive, supportive, inconclusive (no conclusion can be drawn on coherence, either because results are mixed or the data are insufficient), or unsupportive (discordant with the findings from the quantitative research studies). The distinction between supportive and very supportive is based on the magnitude of the reported effect and the directness of the evidence to the question of interest.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 3 |

| Study Infomation | Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008 Prospective pre-post, moderate methodological quality (▲) Hites et al., 2012 Prospective pre-post, moderate methodological quality (▲) Laborde et al., 2013 Cross-sectional (postintervention), poor methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not serious | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Not serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | Large effect (Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008) | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Low |

| Other Evidence | Supportive parallel evidence, no discordant studies | |

| COE | Low (improves PHEPR knowledge of CBP representatives) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Summary of the evidence: Attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives

The committee concluded that there is very low COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve improve attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives regarding their preparedness to meet needs of at-risk individuals. One cross-sectional (postintervention) study (McCabe et al., 2008) provides very low COE regarding the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs on attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives (see Table B1-3), and no supporting evidence from other sources was identified.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 1 |

| Study Infomation | McCabe et al., 2008 Cross-sectional (postintervention), poor methodological quality (▲) | |

| Risk of Bias | Very serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not applicable | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | No | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Very low |

| Other Evidence | No | |

| COE | Very low (improves preparedness attitudes and beliefs of CBP representatives) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Summary of the evidence: CBP disaster planning

The committee concluded that there is very low COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve increase CBP disaster planning. One quantitative comparative study (McCabe et al., 2014a,b) and one cross-sectional (postintervention) study (McCabe et al., 2013) provide very low COE regarding the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs on CBP disaster planning (see Table B1-4), and no supporting evidence from other sources was identified.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 2 |

| Study Infomation | McCabe et al., 2014a,b Prospective pre-post, moderate methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2013 Cross-sectional (postintervention), moderate methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not serious | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Not serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | No | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Very low |

| Other Evidence | No | |

| COE | Very low (increases CBP disaster planning) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Summary of the evidence: PHEPR knowledge of trained at-risk populations

The committee concluded that there is moderate COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve improve the PHEPR knowledge of trained at-risk populations. Two quantitative comparative studies (Eisenman et al., 2014; McCabe et al., 2014a,b) and two cross-sectional (postintervention) studies (McCabe et al., 2011, 2013) provide moderate COE regarding the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs on PHEPR knowledge of trained at-risk representatives (see Table B1-5). Despite supportive parallel evidence (described above) and the absence of studies with discordant results, the weight of the evidence was insufficient to upgrade the COE.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 4 |

| Study Infomation | Eisenman et al., 2014 Randomized controlled trial (RCT), moderate methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2014a,b Prospective pre-post, moderate methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2011 Cross-sectional (postintervention), poor methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2013 Cross-sectional (postintervention), poor methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not serious | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Not serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | No | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Moderate |

| Other Evidence | Supportive parallel evidence, no discordant studies | |

| COE | Moderate (improves PHEPR knowledge of at-risk populations) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Summary of the evidence: Preparedness attitudes and beliefs of trained at-risk populations

The committee concluded that there is low COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve improve attitudes and beliefs of trained at-risk populations regarding their preparedness. Two quantitative comparative studies (McCabe et al., 2014a,b; Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008) and one cross-sectional (postintervention) study (McCabe et al., 2011) provide low COE regarding the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs on preparedness attitudes and beliefs of trained at-risk representatives (see Table B1-6), and no supporting evidence from other sources was identified.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 3 |

| Study Infomation | Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008 Prospective pre-post, moderate methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2014a,b Prospective pre-post, poor methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2011 Cross-sectional (postintervention), poor methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not serious | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Not serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | Large effect (Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008) | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Low |

| Other Evidence | No | |

| COE | Low (improves attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Summary of the evidence: Preparedness behaviors of trained at-risk populations

The committee concluded that there is moderate COE that culturally tailored preparedness training programs for CBPs and at-risk populations they serve improve preparedness behaviors of trained at-risk populations. Four quantitative comparative studies (Eisenman et al., 2009, 2014; McCabe et al., 2014a,b; Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008) provide moderate COE regarding the effects of culturally tailored preparedness training programs on preparedness behaviors of trained at-risk representatives (see Table B1-7). Despite supportive parallel evidence (described above) and the absence of studies with discordant results, the weight of the evidence was insufficient to upgrade the COE.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 4 |

| Study Infomation | Eisenman et al., 2009 Randomized controlled trial (RCT), moderate methodological quality (▲) Eisenman et al., 2014 RCT, moderate methodological quality (▲) Montgomery County Department of Health and Human Services, 2008 Prospective pre-post, moderate methodological quality (▲) McCabe et al., 2014a,b Prospective pre-post, poor methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not serious | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Not serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | No | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Moderate |

| Other Evidence | Supportive parallel evidence, no discordant studies | |

| COE | Moderate (improves preparedness behaviors of at-risk populations) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Engagement of CBPs in Preparedness Outreach Activities Targeting At-Risk Populations

Evidence from quantitative research studies

One quantitative comparative study examined the effect of engaging CBPs in preparedness outreach activities targeting at-risk populations. The study conducted by Coady and colleagues (2008) used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to engage CBPs in the design and implementation of a community-based intervention aimed at increasing interest in influenza vaccination in economically disadvantaged, difficult-to-reach populations (e.g., substance abusers, undocumented immigrants) residing in urban settings. Although the intervention was implemented in the context of seasonal influenza, it was developed with the intent that it could be used to increase vaccination rates during a pandemic influenza scenario, and the committee mapped interest in influenza vaccination to its analytic framework for this practice (see Figure B1-1) as a measure of at-risk population attitudes toward preparedness behaviors. In addition to CBPs’ engagement in the design of the rapid vaccination intervention, CBP venues were leveraged during implementation as sites for information dissemination and vaccination to increase access to difficult-to-reach populations (vaccination and informa-

tion dissemination also occurred door to door and at street-based venues). The study, which used a nonconcurrent nonrandomized comparative design (the same individuals were not sampled before and during the intervention), showed that interest in vaccination was higher in populations queried during the program (N = 3,082) compared with interest levels in the population (N = 3,744) queried prior to the program (adjusted odds ratio 2.69, 95 percent confidence interval 2.17 to 3.33) (Coady et al., 2008).

Other evidence that may inform effectiveness

Although the committee considered parallel evidence, the studies included in the systematic reviews of community engagement strategies generally did not address outcomes related to improved attitudes and beliefs. Therefore, this evidence could not be applied to the assessment of the effect of CBP engagement in preparedness outreach activities on attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations. The committee also considered evidence from a single case report addressing the effects of CBP inclusion in outreach activities on at-risk population attitudes toward preparedness behaviors (vaccination). Plough and colleagues (2011) describe the development of partnerships with CBPs in Los Angeles County, California, to address low vaccination rates among African American populations during the H1N1 outbreak and associated trust issues. The authors indicate that 31,166 vaccinations were administered at 580 vaccination outreach events conducted by the public health department and community partners. CBPs also provided information and referred 6,000 clients to free or low-cost vaccination providers. There were no studies with discordant results.

Summary of the evidence: Engagement of CBPs in preparedness outreach activities targeting at-risk populations

The committee concluded that there is very low COE that CBP engagement in preparedness outreach activities improves the attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations toward preparedness behaviors. One quantitative comparative study (Coady et al., 2008) provides very low COE regarding the effect of CBP engagement in preparedness outreach activities on the attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations (see Table B1-8), and the evidence from the single very supportive case report (Plough et al., 2011) was insufficient to upgrade the COE.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 1 |

| Study Infomation | Coady et al., 2008 Nonrandomized comparative study (NRCS), poor methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Very serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not applicable | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | No | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Very low |

| Other Evidence | One very supportive case report, no discordant studies | |

| COE | Very low (improves attitudes and beliefs of at-risk populations) | |

NOTE: Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

Engagement and Training of CBPs in Coalitions Addressing Public Health Preparedness/Resilience

Evidence from quantitative research studies

One quantitative comparative study examined the effect of engaging multiple CBPs in coalitions and training them in PHEPR concepts on system-level outcomes related to improving outcomes for at-risk populations. Williams and colleagues (2018) describe results from an RCT in which 16 community coalitions in Los Angeles County, California, were randomized to use and receive training in either community resilience or enhanced standard preparedness as an organizing frame for engagement activities. The trial was conducted starting in 2013–2014 and followed for 1–2 years through 2015.

Over the course of the trial, various apparently post hoc analyses were conducted. Reported outcomes of interest include size and diversity of coalitions and coordination among coalition members. Differences in coalition diversity (number of sectors represented) and size favored the resilience group, but the difference was not statistically significant for coalition size. Process activities decreased and integrated activities (greater degree of coordination among coalition members) increased over the first year for both coalition types, although the effect was greater for the preparedness group (no statistical analysis) (Williams et al., 2018). A separately published article on the study shows that both types of coalitions pursued activities focused on reaching and educating vulnerable populations, another outcome of interest, although there is no statistical analysis to support conclusions regarding the relative effects of the two training strategies on this outcome. As evidenced by frequency count data, resilience coalitions focused more on intensive but lower-reach trainings, while

preparedness coalitions relied more on “low-touch” fairs. The resilience coalitions conducted five times as many trainings for vulnerable groups (20 versus 4) (Bromley et al., 2017).

Other evidence that may inform effectiveness

There was no supporting evidence from other sources for this practice.

Summary of the evidence: Engagement and training of CBPs in coalitions

The committee concluded that there is very low COE that CBP engagement and training in coalitions addressing public health preparedness/resilience increases the diversity of coalitions, the coordination of CBPs with other response partners, or the capacity to reach and educate at-risk populations before an emergency. One quantitative comparative study (results described in Bromley et al., 2017, and Williams et al., 2018) provides very low COE regarding the effects of engagement and training of CBPs in preparedness/resilience coalitions on diversity of coalitions, coordination of CBPs with response partners, and the capacity to reach and educate at-risk populations (see Table B1-9), and no supporting evidence from other sources was identified.

| Quality Assessment | Number of Studies | 1 |

| Study Infomation | Bromley et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2018 Randomized controlled trial (RCT), poor methodological quality (▲) |

|

| Risk of Bias | Very serious | |

| Inconsistency | Not applicable | |

| Indirectness | Not serious | |

| Imprecision | Serious | |

| Publication Bias | Unlikely | |

| Upgrade for Large Effect, Dose Response, Plausible Confounding | No | |

| Summary of Findings | Initial Certainty of the Evidence (COE) | Very low |

| Other Evidence | No | |

| COE | Very low (increases diversity of coalitions, coordination of CBPs with response partners, or capacity to reach at-risk populations) | |

NOTES: For each outcome, the effects for the two interventions evaluated in the two randomized controlled trial study arms were considered together given the similarity of the interventions (preparedness and resilience training). Effect direction: upward arrow (▲) = improvement/beneficial effect; downward arrow (▼) = harm/negative effect; sideways arrows (◄►) = no effect; up and down arrows (▲▼) = mixed effect/conflicting findings.

2. Balance of Benefits and Harms

Synthesis of Evidence of Effect

Engagement and culturally tailored training of CBPs may have benefits related to improved PHEPR-related knowledge among CBP representatives, particularly knowledge related to at-risk populations (low COE). Training of at-risk populations by or alongside CBP representatives may in turn improve the PHEPR knowledge of those populations (moderate COE) and may prompt at-risk individuals to engage in protective behaviors (e.g., stockpiling critical supplies, developing a communication plan, expanding social networks) (moderate COE). Such training may also improve the attitudes and/or beliefs of at-risk populations regarding their preparedness (low COE). However, there is little evidence linking preparedness phase outcomes (e.g., improved knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and preparedness behaviors) with health and other outcomes for at-risk populations after an event. No evidence of harms is reported in the quantitative studies.

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Twenty qualitative studies (Andrulis et al., 2011; Bromley et al., 2017; Cha et al., 2016; Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Cordasco et al., 2007; Cuervo et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016, 2018; Hipper et al., 2015; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Kamau et al., 2017; Laborde et al., 2011; Messias et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2015; Peterson et al., 2019; Rowel et al., 2012; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Shih et al., 2018; Stajura et al., 2012) supported a finding that engagement of community-based partners corresponded almost entirely to collaborations (coalitions and partnerships). The effectiveness of such collaborations appears to depend on inclusive membership—which helps members manage capacity constraints—and cooperative and shared goals (high confidence in the evidence). Collaborations with CBPs facilitate (1) inclusion of community organizations (formal or informal) in emergency preparedness and response efforts (Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Gagnon et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2018; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Miller et al., 2015); and (2) awareness and appreciation of the varied community and cultural perspectives and operating characteristics of those organizations (including language, leadership, and decision-making styles) (Bromley et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2019; Rowel et al., 2012; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013). Expanding the number and/or size of collaborations through the inclusion of diverse CBPs better embeds their perspectives in community efforts and strengthens commitments to improving outcomes for all community members, including traditionally at-risk populations (Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Cordasco et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2015; Peterson et al., 2019; Stajura et al., 2012). Engaging those CBPs traditionally underrepresented in community collaborations also helps extend the reach of response partners to some of the highest-risk populations (Ingham and Redshaw, 2017). Inclusive and purposeful collaborations prompted by goals for community-wide emergency preparedness and response may achieve additional benefits, such as cultural sensitivity and appropriateness and shared ownership of community efforts (Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Cordasco et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2015; Peterson et al., 2019). Inclusive approaches to CBP engagement may also serve to enhance trust in government initiatives (Cordasco et al., 2007; Gin et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2019; Rowel et al., 2012).

A frequently noted perceived benefit of collaborations is improved awareness among public health departments of the CBPs in the community and the services they provide, as well as improved understanding among CBPs of the services and activities of public health agencies (Bromley et al., 2017; Cuervo et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016;

Laborde et al., 2011; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Shih et al., 2018). Collaborations appear to provide all members with a means of learning and understanding each other’s roles during routine operations. Such shared knowledge in turn provides the basis for leveraging and coordinating existing services when emergency events occur. Similarly, such knowledge is foundational for identifying and developing strategies for covering gaps in services, which may improve preparedness and coordination of response related to community-wide public health emergencies (high confidence in the evidence). This finding is supported by nine qualitative studies (Andrulis et al., 2011; Bromley et al., 2017; Cuervo et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2018; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Laborde et al., 2011; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Shih et al., 2018). Collaborations may also help CBPs integrate preparedness efforts into their core services (Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Shih et al., 2018).

Collaborations with CBPs provide an opportunity for relationship building for nonemergency purposes. Collaborations appear to nurture relationships developed through preparedness efforts that may not lead immediately to leveraging or developing services, but may assist with informal and emergent responses during an emergency (Bromley et al., 2017; Cha et al., 2016; Cuervo et al., 2017, Gin et al., 2016; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Shih et al., 2018; Stajura et al., 2012). Successes experienced by collaborations may foster ongoing and new multisectoral collaborative efforts, as well as member commitment (Gagnon et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Peterson et al., 2019).

Participatory approaches to CBP engagement may improve the capacity of stakeholders (Andrulis et al., 2011; Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Gagnon et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2015). For example, collaborations may be effective at finding ways to bypass administrative constraints experienced by CBPs or may assist with obtaining funding using collective rather than competing strategies among members (Gagnon et al., 2016; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017). These are likely to be perceived and experienced as benefits.

At the same time, the body of qualitative studies notes several potential harms and/or undesirable impacts of CBP engagement. Participatory approaches to CBP engagement may be risky in that implicit biases may surface as explicit biases. Miller and colleagues (2015) report that this occurred when discussion included “issues that often go unsaid in communities,” and some typically marginalized members challenged assumptions that may privilege certain populations or perspectives over others. Although some may welcome the opportunity to confront this terrain, the process involved in addressing such biases constructively is often difficult and resisted (Miller et al., 2015). When approaches are less than participatory, foundational elements of what is valued, what is considered knowledge, what is considered actionable knowledge, and who is in control remain uncontested. This observation, which emerged from the body of qualitative studies (both directly and as an analytic interpretation), represents both a barrier to working together and a perceived harm of preparedness efforts (Andrulis et al., 2011; Cordasco et al., 2007; Gin et al., 2016; Hipper et al., 2015; Kamau et al., 2017; Laborde et al., 2011; Messias et al., 2012; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Stajura et al., 2012).

Negative experiences from past collaborative relationships may pose barriers to future engagement efforts if potential members think that collaborations do not result in constructive relationships or seldom produce desired results (Stajura et al., 2012). Past failures may be attributed to poor cultural sensitivity within collaborations or conflicts over decision-making principles (notably hierarchical versus consensus approaches) (Andrulis et al., 2011; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017). CBPs may perceive that certain members tend to experience more recognition than others (Laborde et al., 2011; Stajura et al., 2012) or do not provide evidence-based, honest, or reliable information (Andrulis et al., 2011; Charania and Tsuji, 2012); exhibit “egos” and form “gangs” (Cha et al., 2016; Stajura et al., 2012); or are not

trustworthy (Cha et al., 2016). Also noted as a concern is the potential for engagement efforts to be token rather than substantive when collaboration is mandated by external government standards or funders (Gin et al., 2016).

Collaborative partners may express frustration when they perceive a short-term rather than sustained focus on emergency preparedness. It needs to be acknowledged that collaboration building is usually a slow process, one complicated by ongoing personnel changes (and resulting loss of institutional memory) within CBPs (Cha et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016; Hipper et al., 2015; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Peterson et al., 2019; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013). Although Charania and Tsuji (2012) observe that collaborative work is not always a long-term endeavor, in most instances, the often limited and short-term funding provided for this work impedes building and sustaining collaborations, and may result in unintended consequences and harms such as collaboration fatigue, which may also exacerbate trust and confidence issues (Gin et al., 2016, 2018; Peterson et al., 2019; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013).

Specifically with regard to training, when there are no opportunities to deliberatively practice learning obtained through training, training becomes an isolated event with no transfer to the workplace, whether for routine or emergency operations (Cuervo et al., 2017). These factors not only create barriers to assessing the effectiveness of training and knowledge transfer, but likely cause harm by potentially creating disenchantment with the usefulness of any training.

Case Report Evidence Synthesis

While case reports included in this review address only benefits of engaging CBPs, unintended consequences may have occurred but not been known or described. Overall, however, case report findings indicate positive impacts of engaging partners, many of which align with the findings on benefits from other evidence types. These reported benefits include the development of new partnerships, enhanced coordination, the potential for surge staffing during an emergency, and improved preparedness and readiness to serve at-risk populations. In support of the qualitative evidence synthesis findings, case reports suggest that engagement and training of direct service personnel, FBOs, and other community partners also present opportunities for leveraging the distinctive capabilities of each, as well as for capacity development. In Philadelphia, an outreach model that included training, education, bidirectional communication via dissemination of quarterly health bulletins to CBOs serving vulnerable populations, and inclusion of evaluation practices was found to increase preparedness and local capacity to prepare for and respond to the needs of vulnerable populations during an emergency (Klaiman et al., 2010). Another case report describes how a statewide tribal public health emergency preparedness network was perceived to have been strengthened as the result of a training collaboration among statewide tribal partners; the Arizona Department of Health Services; and the College of Public Health at the University of Arizona (Peate and Mullins, 2008), which tailored trainings to the unique public health concerns of the tribal communities.

Case reports suggest further that new and strengthened partnerships with CBPs developed through engagement and training efforts can support increased reach to underserved communities before and during a public health emergency. For example, targeted outreach to key community leaders aimed at increasing H1N1 vaccination of African Americans in Los Angeles County resulted in new partnerships with CBPs that were well positioned to extend the reach of public health messaging within the African American community and expanded locations willing to allow on-site vaccinations (Plough et al., 2011). Los Angeles County’s experience indicates that integration of public health preparedness within routine

prevention messages and community engagement strategies can maximize both effectiveness and efficiency, as well as build trust prior to a public health emergency.

Another benefit of engaging CBPs is improved cultural competency and alignment with the needs of underserved populations. Review findings suggest that including underserved populations in emergency planning, training, and exercises can increase understanding of the needs and expectations of these populations (Chandra et al., 2015; Cripps et al., 2016; Howard et al., 2006; Klaiman et al., 2010; Levin et al., 2014; McCabe et al., 2011; Peate and Mullins, 2008). Case reports also describe improved trust resulting from ongoing engagement. Several case reports emphasize the importance of building trust with CBPs prior to emergencies, as they are often the trusted sources of information for underserved communities (Klaiman et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2013). Some communities may have an underlying historical mistrust of government services, necessitating more rigorous outreach efforts (Plough et al., 2011, 2013).

Including vulnerable populations in planning processes can raise the level of respect for, trust in, and acceptance of emergency plans among underserved communities. Trust may also be built by developing connections with populations that are not formally served by an agency or provider. Such connections can result from reaching out to neighborhood and grassroots groups, including FBOs and limited-English-speaking communities (Klaiman et al., 2010). Trusted leadership and organizational relationships can also be built by providing safe and supportive environments for bidirectional learning (Kiser and Lovelace, 2019). This is important as the lack of preexisting or fully functional relationships among emergency preparedness agencies, CBOs, and vulnerable communities hinders effective engagement in emergency situations (Cripps et al., 2016; Gebbie et al., 2009; McCabe et al., 2011; Plough et al., 2013). Moreover, a lack of strong relationships may lead to confusion around the roles of CBPs, which can serve as an additional barrier to effective engagement (Koh et al., 2006). Case reports also mention opportunities for shared learning and dissemination of best practices through the development of multilevel networks of learning communities, collaborative exercises, and the establishment of trusted relationships that may allow for more rigorous evaluation methodologies and quality improvement (Chandra et al., 2015; Kiser and Lovelace, 2019; Klaiman et al., 2010). Finally, outcomes may be improved by engaging trusted local networks that share a commitment to eliminating health disparities; using a framework of strengths and assets; and providing a safe, supportive, multilevel learning community (Kiser and Lovelace, 2019; McCabe et al., 2011, 2013).

3. Acceptability and Preferences

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

The body of qualitative studies indicated that CBPs were generally supportive of community preparedness goals and strategies for engagement and training, valuing both representation (inclusion) and involvement (shared ownership). Pushback was most often attributable to issues of nonparticipatory approaches or capacity. CBPs emphasized their everyday roles in serving at-risk individuals and stated that they would continue providing those services during emergencies (Messias et al., 2012). Accordingly, they stressed the need to be involved in planning and preparedness for emergencies at the community level—which also would help with coordination efforts—and the need to identify and strengthen services that could be leveraged during emergency responses (Andrulis et al., 2011; Bromley et al., 2017; Cha et al., 2016; Charania and Tsuji, 2012; Cordasco et al., 2007; Cuervo et al., 2017; Eisenman et al., 2009; Gin et al., 2016; Hipper et al., 2015; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Kamau et

al., 2017; Miller et al., 2015; Peterson et al., 2019; Rowel et al., 2012; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Stajura et al., 2012).

Leadership support has been found to influence acceptability. Leaders are crucial to establishing the importance of preparedness and commitment to participation in preparedness efforts (Cuervo et al., 2017). Four qualitative studies (Bromley et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016; Hipper et al., 2015; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013) indicate that collaborations are more likely to be effective when CBPs have their leaders’ support for cooperative engagement (moderate confidence in the evidence). Two qualitative studies (Hipper et al., 2015; Laborde et al., 2011) similarly support a finding that when participating in training, CBP employees and volunteers are more likely to engage when they have the unambiguous support of their leadership and organizational culture (moderate confidence in the evidence).

Case Report Evidence Synthesis

None of the case reports reviewed for this report addresses in detail acceptability and preferences related to engagement strategies. As with the evidence from qualitative studies, the case report evidence suggests that participatory, collaborative approaches for ensuring the participation of key stakeholders early on in planning processes may facilitate effective engagement. For instance, stakeholder engagement in the development of accessible culturally appropriate emergency preparedness messages has been noted as an important facilitator of effective engagement (Bouye et al., 2009; Cripps et al., 2016; Klaiman et al., 2010; Levin et al., 2014; McCabe et al., 2013; Peate and Mullins, 2008; Wells et al., 2013). A commitment to transparency can also help build the trust needed for effective engagement (Kiser and Lovelace, 2019; Wells et al., 2013).

Case reports address as well the role of organizational culture in facilitating effective engagement (Plough et al., 2013; Wells et al., 2013). For instance, public health departments may need to undergo an internal culture change to both embrace and align with a community-partnered approach. Additionally, emergency preparedness staff may need to develop new skill sets that go beyond traditional individual- and family-focused preparedness efforts to better encompass community coordination, neighborhood planning, and integration with nonemergency community-based activities. Reframing public health emergency preparedness practices to include a commitment to leveraging existing community health activities, along with a strong emphasis on health equity in all activities, can facilitate this organizational shift toward collaborative strategies and community preparedness (Plough et al., 2013).

Descriptive Survey Study Evidence

Two descriptive surveys support the finding from the qualitative evidence synthesis that CBPs generally are supportive of engagement in PHEPR activities and are willing to collaborate with public health, although social desirability bias may influence their reported willingness to collaborate. Baezconde-Garbanati and colleagues (2006) report that 70 percent of surveyed CBOs and nongovernmental organizations serving the Hispanic community across 12 U.S. states were willing to provide services to their community during a large-scale emergency, and most were willing to establish linkages with other organizations to help them become better integrated into emergency planning and management at the local level (74 percent preferred to link with public health agencies), given proper coordination and resources. Agencies were also willing, contingent on funding, to offer additional services to help prepare for an emergency, including the dissemination of information to Hispanic communities through formal and informal channels, which the majority believed public health

departments could not accomplish adequately because of a lack of cultural proficiency and language resources. Ablah and colleagues (2010) surveyed local health departments (LHDs) and community health centers (CHCs) in 23 states and found that roughly 97 percent of respondents were willing to collaborate with their neighboring LHD or CHC in emergency preparedness or response activities.

Three descriptive surveys support the findings from the qualitative evidence synthesis that leadership support is an important facilitator for the acceptability of PHEPR-related engagement and training. Wineman and colleagues (2007) found that 22 percent of CHCs cited lack of strong leadership and poor coordination of efforts among stakeholders as barriers to their integration into community preparedness activities. Chi and colleagues (2015) report that 11 percent of Los Angeles County Department of Public Health staff cited lack of leadership support as a challenge to building partnerships with community partners, and 10 percent indicated that partnership building did not align with a program priority. Although not specific to CBP engagement, a national survey of LHDs found that higher-intensity community engagement in PHEPR more broadly was associated with having a formal community engagement policy, funds being allocated for community engagement, receiving strong support from CBOs, and having a coordinator with prior community engagement experience (Schoch-Spana et al., 2015).

4. Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

The body of qualitative studies suggests that participatory collaborations and targeted, tailored training are feasible. Although collaborations and trainings can in fact alleviate capacity concerns in some cases, there remain perceived capacity limits, likely to be exacerbated in an emergency (Hipper et al., 2015; Stajura et al., 2012), that serve as a barrier to engagement.

In qualitative studies, CBPs often reported capacity concerns with respect to the delivery of routine services. Nearly all worried about emergencies because such events would increase needs, with concomitant increases in demand for services, and stated that an emergency would stress already stretched human and nonhuman resource capacities (Andrulis et al., 2011; Gin et al., 2016, 2018; Hipper et al., 2015). The more poorly funded a community partner was, the sooner and more deeply these constraints would be felt (Gagnon et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017). Because it is the less well-funded community partners (often those that are more grassroots, faith based, volunteer based, and emergent) that often serve the most vulnerable populations, they may be the first to experience overwhelmed capacities (Andrulis et al., 2011; Gin et al., 2018; Laborde et al., 2011; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013).

The move toward increasing collaborations frequently runs up against CBPs’ concerns over competing priorities (routine versus emergency) and overextended capacities (Cha et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016; Hipper et al., 2015; Shih et al., 2018). Moreover, large collaborative efforts may be considered too expensive, as well as labor intensive (Charania and Tsuji, 2012). Staff turnover, funding limits, and unrealistic expectations for quick successes compound these challenges (Cha et al., 2016; Gin et al., 2016; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Peterson et al., 2019; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013). However, a few studies found that collaborations served as a forum for identifying strategic opportunities. When collaboration members improved their understanding of other CBPs’ services, leveraging and coordination of services could expand rather than stress capacities (Cuervo et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016;

Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Laborde et al., 2011). Collaborations may expand capacities through coordination, and may help identify new funding and new opportunities, such as working with emergent groups (high confidence in the evidence). This finding is supported by seven qualitative studies (Bromley et al., 2017; Cuervo et al., 2017; Gagnon et al., 2016; Ingham and Redshaw, 2017; Messias et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2015; Peterson et al., 2019).

Specifically with regard to training, when possible, sponsorship of trainings and provision of monetary incentives may encourage participation and engagement in training activities while minimizing accessibility barriers due to affordability issues (Bromley et al., 2017; Cha et al., 2016; Cuervo et al., 2017; Gin et al., 2016; Hipper et al., 2015; Kamau, 2017; Laborde et al., 2011, 2013).

Case Report Evidence Synthesis

Few case reports address the feasibility of their engagement strategies, although two cite the successful recruitment of CBPs and their willingness to participate in collaborations as evidence of the feasibility of engagement and training initiatives (McCabe et al., 2011, 2013). Still, many note that limited capacity, time, and resources of CBOs, such as CHCs and tribal organizations, can impede engagement because of issues of understaffing, employee turnover, and competing priorities (Chandra et al., 2015; Gebbie et al., 2009; Klaiman et al., 2010; Koh et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2014; Peate and Mullins, 2008). With regard to leveraging FBOs, legal issues regarding separation of church and state are also noted as a potential area for concern (Kiser and Lovelace, 2019; McCabe et al., 2013; Plough et al., 2011). Guidelines in accordance with the U.S. and state constitutions that include nondiscriminatory requirements, separation of public health services and religious activities, and no furthering of religious activities may be helpful in addressing this issue (Kiser and Lovelace, 2019).

Descriptive Survey Study Evidence

Five descriptive surveys support the finding from the qualitative evidence synthesis regarding capacity constraints (e.g., human resources, funding) as a commonly cited barrier to engagement and training (raised by both the CBPs and public health agencies). Baezconde-Garbanati and colleagues (2006) report that among Hispanic-serving CBOs that had recently participated in an emergency response, 50 percent said their resources and capabilities had been exceeded when responding, and 96 percent of those surveyed indicated they received little or no funding for public health emergency preparedness. Regarding commonly experienced barriers to integration into community preparedness activities, a national sample of CHCs cited a number of resource and capacity limitations, including staff limitations and time constraints (70 percent), lack of funding for training and equipment (59 percent), and lack of reimbursement (20 percent), as well as the perception that the role of the CHC is not understood by community emergency planners (57 percent) (Wineman et al., 2007).

Adams and colleagues (2018) surveyed LHD preparedness directors nationally and used a multiple linear regression model to identify characteristics of LHDs that enhance collaborations with CBOs and FBOs for emergency preparedness and response. The survey results highlight the importance of LHD staff capacity. Bevc and colleagues (2014) found that with regard to barriers to establishing and maintaining partnerships, 60 percent of LHD respondents reported lack of resources to train community partners, 41 percent cited concerns about high staff turnover, and 37 percent reported lack of skilled and/or experienced staff. When identifying challenges to partnership building with CBPs, staff of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health cited lack of training on engagement (23 percent),

burden of maintaining relationships (12 percent), capacity limitations of CBPs (15 percent), perception of lack of trust by CBPs (5 percent), and lack of interest from the community (10 percent) or the public health staff (14 percent) (Chi et al., 2015).

5. Resource and Economic Considerations

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

As discussed above, CBPs may perceive participation in collaborations and training related to PHEPR as doing more with no concomitant increase in resources or funding (Cha et al., 2016). This dynamic often discourages collaboration and, to a lesser degree, participation in trainings. It is therefore important to leverage current practices and frame preparedness efforts as an adaptation of existing activities rather than as additional services (Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Stajura et al., 2012).

Importantly, the qualitative studies included in this review indicate that building and maintaining collaborations requires long-term investment (Cha et al., 2016; Schoch-Spana et al., 2013; Stajura et al., 2012). If federal policy makers decide to embrace and promote collaborations and training, they will need to do so with an understanding of the need for longitudinal funding and appropriate outcome evaluations (Gin et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2019; Stajura et al., 2012), which also require dedicated financial support (Kamau et al., 2017).

Case Report Evidence Synthesis