Summary1

Communities across the nation are facing increasingly complex public health emergencies that are responsible for loss of life, disruption of the social fabric of society, and unprecedented damages and costs. State, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies routinely make difficult decisions about how to respond effectively to a wide range of public health threats (e.g., infectious disease epidemics, natural and human-made disasters) and prepare for worst-case scenarios, including chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear events. Yet, the existing scientific evidence base that informs the actions of SLTT public health agencies in preparing for and responding to these emergencies is sparse and uneven, and fails to meet the needs of public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) practitioners for clear and accessible guidance. This deficiency impedes the efforts of these dedicated professionals who work tirelessly to protect the lives and health of the people of this country and threatens the nation’s health security. This report calls for a transformation in the infrastructure, funding, and methods of PHEPR research to ensure that PHEPR practice is grounded in robust evidence for what works, where, why, and for whom.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

Study Charge

In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent anthrax bioterrorism attacks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other governmental and nongovernmental organizations together invested billions of dollars and immeasurable human capital to develop and enhance PHEPR infrastructure, systems, and science. Since 2011, 15 foundational Capabilities—defined in CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public

___________________

1 This Summary does not include references. Citations for the discussion presented in the Summary appear in the subsequent report chapters.

Health—have guided public health agencies in building and sustaining robust systems to prevent, protect against, quickly respond to, and recover from public health emergencies. The PHEPR Capabilities alone do not constitute the PHEPR system; rather, the system comprises the interactions among the Capabilities and the context in which they are operationalized. As a result, those PHEPR practices2 that fall within the PHEPR Capabilities are often complex, are generally implemented simultaneously with an array of other practices, and may target multiple levels (i.e., individual, community, organizational, or systems levels). Thus, it is critical to understand and appreciate the underlying characteristics and relationships of the PHEPR system and to apply this understanding to the design and evaluation of PHEPR practices.

As the nation approaches two decades since the events of September 11, 2001, this is an opportune time to take stock of the state of the evidence on PHEPR practices and the improvements necessary to move the field forward and to strengthen the PHEPR system. Therefore, CDC charged the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine with developing the methodology for and conducting a systematic review3 and evaluation of the evidence for selected PHEPR practices that fall within CDC’s 15 PHEPR Capabilities. The committee was also charged with making recommendations for future research needed to address critical gaps in evidence-based PHEPR practices, as well as processes needed to improve the overall quality of evidence within the field. The full charge to the committee is presented in Chapter 1 of this report.

How This Report Is Organized and Intended to Be Used

Throughout this report, the committee seeks to guide practitioners, researchers, policy makers, funding organizations, and other stakeholders in understanding and using the available evidence to inform their decision making. It also seeks to demonstrate for methodologists and other researchers interested in the field of evidence synthesis and guideline development the application of a mixed-method approach to evidence synthesis and the challenges associated with evaluation of complex interventions, such as those the committee reviewed.

The report is organized around the two distinct aspects of the committee’s charge, each of which comes with its own set of recommendations: (1) recommendations for evidence-based PHEPR practices based on reviews of the evidence for their effectiveness, carried out using the committee’s customized methodology; and (2) recommendations for future research needed to address critical gaps in evidence-based PHEPR practices and processes to improve the overall quality of evidence within the field. The latter set of recommendations, which will be of greatest interest to policy makers and researchers, is presented in Chapter 8, which considers the role that funders, researchers, and practitioners can play in advancing the evidence base. For the four selected PHEPR practices reviewed by the committee, evidence-based practice recommendations and implementation guidance are presented in Chapters 4–7, respectively. These four chapters are oriented to practitioners and include high-level evidence summaries for the four PHEPR practices; each of these chapters opens with a two-page action sheet pro-

___________________

2 In PHEPR, in contrast to clinical medicine, there is seldom a discrete “intervention”; therefore, the committee defined PHEPR practice broadly as a type of process, structure, or intervention whose implementation is intended to mitigate the adverse effects resulting from a public health emergency on the population as a whole or a particular sub-group within the population. PHEPR practices fall within the 15 PHEPR Capabilities.

3 Although the term “comprehensive review” was used in the committee’s Statement of Task (see Box 1-1), the committee uses the field-accepted term “systematic review” throughout this report. The committee applied a mixed-method approach to its systematic review.

viding key takeaways for practitioners. For those audiences seeking additional, more detailed information, each of these four chapters has an associated appendix (see Appendixes B1–B4) containing a comprehensive description of the evidence base for the respective PHEPR practice. To facilitate the linkage between the evidence summaries in the four chapters and the detail in the corresponding appendixes on the body of studies from which the chapter findings were generated, each of the four chapters references specific numbered sections in the respective appendix. Chapter 3 describes the committee’s proposed methodology for reviewing and evaluating the evidence for PHEPR practices and is likely to be most relevant for methodologists and others interested in applying or adapting the methodology.

This Summary and the preceding Abstract are oriented to policy makers who will be responsible for implementing the committee’s recommendations. To facilitate a focus on the key policy issues, the recommendations in the Abstract and Summary are presented in a different sequence from that used in the report chapters. Specifically, Recommendations 1 and 2 are presented after Recommendation 7 in this Summary.

IMPROVING AND EXPANDING THE EVIDENCE BASE FOR PHEPR

State of the Evidence and Underlying Reasons

The findings from the committee’s four PHEPR practice evidence reviews (described below) and a broader scoping review of the evidence for the PHEPR Capabilities (discussed in Chapter 2) are generally consistent with previously published reviews of the PHEPR research landscape. Despite an increase in published empirical studies over the past two decades, attributable in part to the investments made in preparedness and response research centers after September 11, 2001, and the subsequent anthrax attacks, the body of PHEPR research remains overwhelmingly descriptive, lacking in objective evaluations using validated measures that are capable of supporting conclusions on practice effectiveness. Existing PHEPR research also is notably uneven across the 15 Capabilities, with few (and in some cases no) impact studies for the majority of PHEPR practices evaluated in the committee’s commissioned scoping review. The picture that emerges is that of a field based on longstanding rather than evidence-based practice.

Currently, the PHEPR field is relying on fragmented and largely uncoordinated research efforts. PHEPR research funding, and the field as a whole, moves from one disaster to the next with little continuity, and with investments generally inversely proportional to the time since the last event. The lack of stable funding for PHEPR research creates inefficiencies as the field rebuilds and then deconstructs its research infrastructure and workforce capacity with each new emergency. Moreover, research investments related to mitigating the effects of public health emergencies have been skewed toward more traditional biomedical research. For example, annual federal investments in research and development for medical countermeasures have ranged from $1.6 to $1.8 billion since 2004. In contrast, total 10-year research funding (2008–2017) for the Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration Capability was estimated at just over $100,000 in one recent study. This extreme imbalance positions public health emergency response for failure, as practitioners lack fundamental knowledge regarding how to best distribute the countermeasures the nation invested billions of dollars to produce.

Overall, the committee concluded that the science underlying the nation’s response to public health emergencies is seriously deficient, hampering the nation’s ability to respond to emergencies most effectively to save lives and preserve well-being. Significant advances are needed to improve and expand the evidence base for PHEPR practices.

Developing a National PHEPR Science Framework

In the absence of a system to support coordination and collaboration in the conduct of PHEPR research, academic researchers will continue to face numerous barriers to the conduct of this research, and much of the evidence base for PHEPR practices will continue to reflect a series of one-off studies that lack the comparability necessary to address knowledge gaps important to policy makers and practitioners. Addressing those knowledge gaps will require sustained lines of research, with multiple studies addressing similar research questions in different contexts and populations. An enduring national framework is needed to establish goals and objectives for improving coordination, integration, and alignment among existing but often fragmented PHEPR research efforts, and specifically to direct and coordinate available research funding to address prioritized PHEPR knowledge gaps most effectively (see Figure S-1). Through the development of such a national framework, the com-

mittee proposes steps to ensure the systematic and continuous development of knowledge in the PHEPR field and sets forth the aspirations for high-quality, rigorous PHEPR research and evaluation that can in turn guide practice.

Given the complexity of the PHEPR research landscape, strong leadership at all levels, but especially at the federal level, is central to the framework and essential to support systems-level change and mobilize relevant agencies to transform the way PHEPR research is coordinated, funded, and conducted. An interagency and multidisciplinary effort, led by CDC, will be necessary to develop and implement the proposed National PHEPR Science Framework; establish an authority and process for supporting high-quality, rigorous, and sustainable research before, during, and after public health emergencies; and ensure that adequate research funding, capacities, and infrastructure are in place. CDC is the funding agency with the primary mission responsibility in PHEPR, and it is important that the agency responsible for supporting PHEPR planning and implementation also lead efforts to increase the scientific evidence base that supports the execution of that responsibility. However, the committee acknowledges that no one agency can accomplish this transformation of the PHEPR research enterprise, and it will be necessary to leverage the strengths of different partners, including funding partners, in these efforts. A critical component of the committee’s proposed framework is the development of a research agenda to galvanize the PHEPR research enterprise to meet the needs and respond to the concerns of PHEPR practitioners and society at large. The process for establishing research priorities should be both top down and bottom up and needs to recognize the transdisciplinary nature of this unique discipline. An important consideration is for the process to be inclusive of governmental, nongovernmental, private, and academic organizations, as well as broad public input from practitioners, policy makers, researchers, and communities.

- Support meaningful partnerships between PHEPR practitioners and researchers, and develop strategies to better ensure that PHEPR research is relevant to practice.

- Prioritize sustainable strategies and mechanisms for the translation, dissemination, and implementation of PHEPR research.

RECOMMENDATION 4: Ensure Infrastructure and Funding to Support Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (PHEPR) Research

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with other relevant funding agencies, should ensure adequate and sustained oversight, coordination, and funding to support a National PHEPR Science Framework and to further develop the infrastructure necessary to support more efficient production of and better-quality PHEPR research. Such infrastructure should include

- sustained funding for practice-based and investigator-driven research that allows for the progression from exploratory to effectiveness to scale-up research and encourages researcher diversity;

- support for partnerships (e.g., with academic institutions, hospital systems, and state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies) to facilitate collaboration in research on the preparedness, response, and recovery phases of a public health emergency;

- development of a rapid research funding mechanism and interdisciplinary rapid response teams with applied research expertise (similar to CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service) for deployment to conduct just-in-time studies related to the implementation of PHEPR practices at the time of events; and

- enhanced mechanisms to enable routine, standardized, efficient data collection with minimal disruption to delivery of services (including preapproved, adaptable research and institutional review board protocols and a research arm within the response structure).

Supporting Methodological Improvements to PHEPR Research and Practice Evaluation

Improving and expanding the evidence base as envisioned through the proposed National PHEPR Science Framework will require incentives for PHEPR researchers and practitioners. As discussed further in Chapter 8, other disciplines (e.g., education) have improved the quality and usefulness of the evidence base by setting priorities and standards for research and using them to guide funding decisions. Similar improvements could be achieved in the PHEPR field if the experiences of these other fields can be leveraged to implement policies and practices that can improve how PHEPR research is conducted, disseminated, and translated into practice. The goal should be to ensure that scarce evaluation dollars are used most productively to advance the evidence available to inform policy and practice. Achieving this goal will necessitate the careful balancing of several factors: the importance of the questions studied, the rigor with which those questions can and will be studied, the timeliness of the research findings, and the accessibility and usability of those findings.

Going forward, there is a need for clear guidelines for evaluation methods and study designs that will produce credible answers to various types of questions important to the PHEPR field. Though important for causal inference, experimental study designs are not the only method for exploring what works in PHEPR (and when, why, and for whom). Well--

crafted guidance will incorporate the full range of research and evaluation methods, from exploratory case studies to randomized controlled trials and modeling studies. Qualitative research methodologies (e.g., ethnographic observations, interviews, and focus group discussions) can inform why and how PHEPR practices may or may not be effective, which may help explain study results or inform intervention design, and can also be useful in generating theories that can be tested empirically. As PHEPR research is transdisciplinary, design methodologies used in such fields as public health services and systems research, operations research, organizational research, and quality improvement can also provide evidence for understanding PHEPR practices. Behavioral and social science approaches may be particularly useful in elucidating contextual factors (social, political, cultural, historical, psychological) that may facilitate or constrain specific PHEPR outcomes. Simulation-based methods (e.g., exercises), systematic expert opinion methodologies (e.g., Delphi’s), and systems science approaches (e.g., social network analyses, causal process diagrams, adaptive systems theories, modeling, machine learning, and big data analyses) can provide insight on systems-level outcomes and the interdependent relationships among the many components of the PHEPR system. Moreover, comprehensive guidance will include suggestions for strategically mixing methods to enhance understanding of the findings, including their breadth and limitations. The PHEPR research community would also be strengthened by the development of a unified taxonomy of research methods, accompanied by guidelines for judging the credibility of study findings intended to address various types of questions. Needed as well are guidelines for reporting the design and results of evaluations of the effectiveness of PHEPR practices to promote the transparency and reproducibility of research, as well as to facilitate implementation in practice settings. Federal funding agencies, professional associations, and journals all have important roles in the adoption of and commitment to reporting standards.

Public health agencies and PHEPR practitioners also need incentives to contribute to expanding the quality of the evidence base. Much of the available PHEPR evidence related

to effectiveness and implementation is currently practice-based evidence that is largely descriptive and generated from evaluations in real-world contexts, such as after action reports (AARs).4 It is vital to determine how to best use this type of evidence for informing practice in the immediate future and to improve its evidentiary value. In particular, though imperfect, AARs have the potential to offer rich information about what works, why, and how, and their use to advance the science could be greatly facilitated if the data they contain were increasingly reliable and capable of being analyzed in a systematic and rigorous manner. To help ensure that future AARs result in more useful and meaningful information for the evaluation of PHEPR practices (including the establishment of credible baselines for evaluation), it will be necessary to focus on strengthening methodological approaches, establishing mechanisms for analysis and dissemination of lessons learned from the reviews, and fostering a culture of improvement.

Training and Supporting the PHEPR Practitioner and Researcher Workforce

Expanding and improving the PHEPR evidence base will depend on developing and supporting PHEPR researchers and practitioners with the skills necessary to ensure the conduct of quality PHEPR research and program evaluation, respectively, and on strengthening

___________________

4 AARs are documents created by public health authorities and other response organizations following an emergency or exercise, primarily for the purposes of quality improvement. They contain narrative descriptions of what was done, but may also contain “lessons learned” (i.e., what was perceived to work well and not well) and recommendations for future responses.

the implementation capacity of SLTT public health agencies. PHEPR practitioners often lack opportunities to develop and maintain research and evaluation skills. Moreover, not everyone is equally suited or professionally able to be both a practitioner and a researcher. It is therefore necessary to develop stronger systems, infrastructure, and norms around the notion of an integrated PHEPR research and practice system that includes both those focused on advancing the science and those applying this knowledge. Such enhancements of workforce capacity, which have the potential to bridge the traditional divide between practice and research, could be achieved through a combination of training, technical assistance, peer networking, and sustainable practitioner–researcher partnerships. On the research side, there has been virtually no investment in the development of a researcher pipeline, a gap that also reflects the relative dearth of funding opportunities for PHEPR research. Ensuring a diverse, adequately trained, and sufficiently available interdisciplinary cadre of disaster researchers will require investment in improved researcher training programs and grants (e.g., career development awards), particularly those aimed at increasing PHEPR research capacity to evaluate complex interventions and present findings in a succinct and accessible manner.

DEVELOPING AN EVIDENCE-BASED PROCESS TO INFORM PHEPR DECISION MAKING

The research and other evidence generated by the proposed National PHEPR Science Framework will be useful to PHEPR practitioners only if it can be synthesized and translated into evidence-based practices. Systems for evaluating the evidence supporting given practices and interventions are a valued resource for practitioners, policy makers, and others

who seek to use the best available evidence for decision making, but who lack the time, resources, or expertise needed to review and interpret a large and potentially inconsistent body of evidence. In response to its charge and to support PHEPR practitioners’ decision making, the committee developed a transparent process for systematically reviewing and evaluating PHEPR evidence and for understanding the balance of benefits and harms of PHEPR practices.

Developing and Applying an Evidence Review and Evaluation Methodology

In developing its methodology, the committee considered ways to address a number of challenges that characterize the PHEPR evidence base. The PHEPR system is an inherently complex one that encompasses policies, organizations, and programs. Its complexity also stems in part from the nature of public health emergencies, which are often unpredictable, may evolve rapidly, and are highly heterogeneous in terms of setting and type (e.g., weather events, disease outbreaks, terrorist events). “Setting” in this context is not limited to geographic location, but also encompasses the sociocultural and demographic environment and the characteristics of the communities and the responding agencies (e.g., organizational structure, managerial experience, capabilities, and resources). PHEPR practices themselves may also be complex, featuring multiple interacting components that target multiple levels (e.g., individual, population, system), and implementation is often tailored to local conditions. Consequently, a considerable challenge when reviewing evidence to determine the effectiveness of PHEPR practices and implementation strategies relates to the often convoluted and uncertain links between practices and important health outcomes (morbidity and mortality), as well as other potential outcomes of interest (e.g., organizational, economic, or social).

Because of these characteristics and based on a review of the literature and discussions with experts,5 the committee concluded that none of the evidence evaluation frameworks it reviewed were sufficiently flexible, by themselves, to be universally applicable to all of the questions of interest to PHEPR practitioners and researchers without adaptation. Nor would existing methods be ideally suited to the context-sensitive nature of PHEPR practices and the diversity of evidence types and outcomes of interest, many of which are at the level of organizations or systems and thus often difficult to measure. Therefore, the committee developed a fit-for-purpose, mixed-method review methodology, drawing on—and in some cases adapting—elements of existing frameworks and approaches that were deemed most applicable to PHEPR, including those of the Community Preventive Services Task Force and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE), as well as GRADE-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) for qualitative evidence. This approach enabled the committee to use the appropriate methodology to answer different types of questions of interest to PHEPR stakeholders.

The committee’s approach also was informed by more recently developed and evolving methods for the review and evaluation of interventions that are complex or implemented within complex systems, methods that focus on the integration of diverse and heterogeneous types of evidence. The PHEPR system draws on a broad evidence base, ranging from randomized controlled trials to surveys, modeling studies, and AARs, and the committee’s methodology needed to accommodate that diversity. In addition to both quantitative and qualitative research-based evidence, the approach makes use of experiential evidence from

___________________

5 The committee held a 1-day public workshop on evidence evaluation frameworks used in health and nonhealth fields, which is documented separately in a Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (see Appendix E).

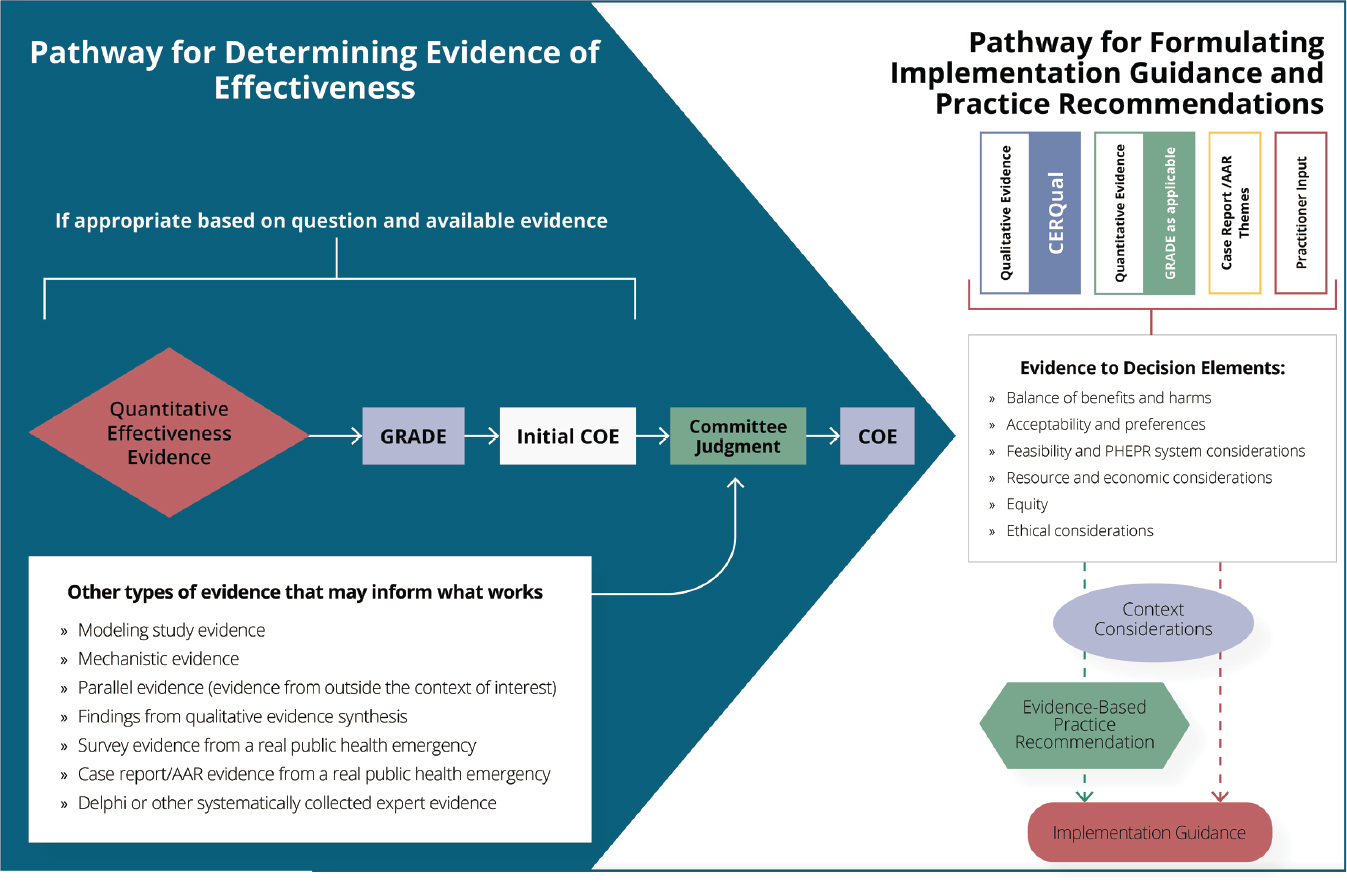

past response scenarios. This feature of the committee’s approach offers the potential for validation of research findings in practice settings, as well as improved understanding of context effects, trade-offs, and the range of implementation approaches or components for a given practice. In applying this approach, nonempiric evidence was mapped onto research findings from quantitative and qualitative syntheses to consider the coherence of evidence from across methodological streams (including evidence from quantitative impact studies, cross-sectional surveys, modeling studies, qualitative studies, case reports, and AARs, as well as parallel and mechanistic evidence6), and thereby to assess the certainty of the evidence (COE) of effectiveness for a practice (refer to the left side of Figure S-2) and develop summary findings for each element of the committee’s Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework (refer to the right side of Figure S-2). The EtD framework enabled the committee to take into account systematically the balance of benefits and harms of a practice, the acceptability of the practice and stakeholder preferences, feasibility and PHEPR system considerations, resource and economic considerations, equity, and ethical issues in decisions regarding practice recommendations.

A key element of the committee’s task was to develop and apply criteria for the selection of PHEPR practices to include in the systematic reviews. Rather than using a sequential approach involving the development of the evidence review and evaluation methodology in the abstract and then applying this methodology to the PHEPR practices selected for review, the committee selected the practices with the intent of using them to simultaneously develop and test the methodology through a highly iterative process, the steps of which are described in detail in Chapter 3. The practice selection criteria, therefore, were developed with the aim of yielding a set of PHEPR practices that would be diverse with respect to both the research and evaluation methodologies used to generate the evidence base for them and their characteristics, such as the type and scope of event in which a practice is implemented, the practice setting, whether the practice is complex or simple, whether it is within the direct purview of public health agencies, and whether it is preparedness or response oriented. This process was intended to result in a methodology that would be applicable across the full range of PHEPR practices. The committee also engaged with stakeholders (PHEPR practitioners and policy makers)7 and referred to published literature identifying practitioners’ research needs to inform the selection of practices to review. This selection process, which is depicted in Figure 3-1, yielded the following four practices8 as the focus of the committee’s review and this report:

- engaging with and training community-based partners to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations9 after public health emergencies (falls under Capability 1, Community Preparedness);

___________________

6 For the purposes of this report, the committee defined mechanistic evidence as evidence that denotes relationships for which causality has been established—generally within other scientific fields, such as chemistry, biology, economics, and physics—and that can reasonably be applied to the PHEPR context through mechanistic reasoning, defined as “the inference from mechanisms to claims that an intervention produced” an outcome.

7 Stakeholder engagement occurred through the committee’s public meetings and through discussions with SLTT PHEPR practitioner consultants appointed to advise the committee on the systematic literature review process. The Delphi-like practitioner engagement activity described in Appendix A was conducted after the committee’s four evidence review topics had been selected and therefore did not inform the selection process. The activity was intended to inform priorities for future PHEPR evidence reviews.

8 The review topics were selected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

9 For the purposes of this report, the committee defined at-risk populations as comprising individuals with social and/or structural vulnerabilities whose access and functional needs may not be fully met by traditional service providers or who feel they cannot comfortably or safely use the standard resources offered during preparedness, response, and recovery efforts. A more comprehensive description of at-risk populations is provided in Box 4-1 in Chapter 4.

NOTES: This framework is intended for those interested in the details of the committee’s methodology for evaluating evidence for PHEPR practices. Depicted are two interconnected pathways. The lefthand panel (blue) shows the committee’s process for integrating evidence from quantitative impact studies with other evidence that may inform what works to determine the certainty of the evidence (COE) of effectiveness for a given outcome. The COE (for all relevant outcomes) feeds into the righthand panel (white), which shows the pathways for integrating diverse evidence for various elements (evidence to decision elements) that, along with context considerations, may inform the formulation of evidence-based practice recommendations and implementation guidance. In cases in which the review is focused on implementation and not on determining the effectiveness of a practice, it is possible to follow the pathway depicted in the righthand panel without assessing the COE as shown in the lefthand panel. Other types of evidence that may inform what works may be used to examine coherence with direct quantitative effectiveness evidence or may be used to inform committee judgment in the absence of direct quantitative evidence. AAR = after action report; CERQual = Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research; COE = certainty of the evidence; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; PHEPR = public health emergency preparedness and response.

- activating a public health emergency operations center (Capability 3, Emergency Operations Coordination [EOC]);

- communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency (Capability 6, Information Sharing); and

- implementing quarantine to reduce or stop the spread of a contagious disease (Capability 11, Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions).

Key findings and practice recommendations for each of these four review topics are presented in Table S-1. A summary of the review findings supporting the practice recommendations and/or implementation guidance for each of these four practices are presented in Chapters 4–7, respectively. The four chapters each begin with a two-page action sheet summarizing key review findings, recommendations, and guidance for practitioners; detailed descriptions of the evidence are provided in Appendixes B1–B4. Despite the limitations of the evidence base—which was often sparse and characterized by a predominance of descriptive reports and studies with notable shortcomings in their design or conduct—and challenges in the application of GRADE to practices that are dependent on context and implementation fidelity, the committee’s mixed-method, layering approach enabled the development of practice recommendations for three of the four review topics. For the fourth topic (activating a public health emergency operations center), the committee was able to draw on qualitative and experiential evidence to identify specific considerations to guide decision making regarding EOC activation, thus demonstrating the utility of the methodology for answering operational questions of interest to PHEPR practitioners concerning implementation even in the absence of evidence of effect.

| Review Topic | Key Review Findings | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Engaging with and training community-based partners to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations after public health emergencies | Culturally tailored preparedness training programs for community-based partners (CBPs) and at-risk populations they serve improve the public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) knowledge (moderate certainty of the evidence [COE]) and preparedness behaviors (moderate COE) of trained at-risk populations. CBPs appear to support and value engagement and training, particularly when implemented using a participatory approach, but capacity limitations for both CBPs and public health organizations should be considered when selecting specific strategies. |

Practice Recommendation: Engaging and training CBPs serving at-risk populations is recommended as part of state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies’ community preparedness efforts so that those CBPs are better able to assist at-risk populations they serve in preparing for and recovering from public health emergencies. Recommended CBP training strategies include

CBP engagement and training should be accompanied by targeted monitoring and outcome evaluation or conducted in the context of research when feasible so as to improve the evidence base for engagement and training strategies. |

| Review Topic | Key Review Findings | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Activating a public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) | Partly because of its long tenure as a common and standard practice, direct research evidence does not focus on whether a PHEOC should be utilized, but rather on how it should be implemented. Experiential evidence from a synthesis of case reports and after action reports (from within and outside of PHEPR) suggests that PHEOCs are probably effective at improving response and may have few undesirable effects in the short term, and speaks to the confidence in the PHEOC model among experienced practitioners across diverse situations. PHEPR practitioners consider activating public health emergency operations to be an acceptable and justifiable practice. The feasibility of this practice is variable, and the evidence highlights several feasibility issues to consider before public health emergency operations are activated. | Activating a PHEOC is a common and standard practice, supported by national and international guidance and based on earlier social science around disaster response. Despite widespread use and minimal apparent harms, there is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of activating a PHEOC or of specific PHEOC components at improving response. This does not mean that the practice does not work or should not be implemented, but that more research and monitoring and evaluation around how and in what circumstances a PHEOC should be implemented are warranted before an evidence-based practice recommendation can be made. |

| Communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency | Electronic messaging systems, such as email, fax, and text messaging, are effective communication channels for increasing technical audiences’ awareness of public health alerts and guidance during a public health emergency (moderate COE). Technologies employed as electronic messaging systems for communicating public health alerts and guidance to technical audiences during a public health emergency to increase awareness and appropriate guidance use have differing impacts. However, the available data are insufficient to support a conclusion as to what technology is best for which audiences in which scenarios. Reported harms are not related to the particular medium, but to how communication strategies are implemented (e.g., alert fatigue/information overload, leaving people out of the messaging loop, guidance not aligning with what is feasible). | Practice Recommendation: Inclusion of electronic messaging channels (e.g., email) is recommended as part of SLTT public health agencies’ multipronged approach for communicating public health alerts and guidance to technical audiences in preparation for and in response to public health emergencies. The practice should be accompanied by targeted monitoring and evaluation or conducted in the context of research when feasible so as to improve the evidence base for strategies used to communicate public health alerts and guidance to technical audiences. |

| Implementing quarantine to reduce or stop the spread of a contagious disease |

Quarantine can be effective at reducing overall contagious disease transmission in the community in certain circumstances (high COE), but can be associated with harms, including

Concerns about undesirable effects and harms may make this practice unacceptable to some communities. Implementing quarantine effectively, especially at a large scale, is very challenging and resource intensive, and the evidence highlights several feasibility issues with respect to implementation. |

Practice Recommendation: Implementation of quarantine by SLTT public health agencies is recommended to reduce disease transmission and associated morbidity and mortality during an outbreak only after consideration of the best available science regarding the characteristics of the disease, the expected balance of benefits and harms, and the feasibility of implementation. |

Enduring Support for Ongoing PHEPR Evidence Reviews

In developing the systematic review and evidence evaluation methodology described above, the committee aimed for a process with sufficient flexibility not only to accommodate the diversity of evidence for the four selected PHEPR practices but also to be applied and adapted as needed to support future PHEPR evidence reviews. While the committee acknowledges that tools other than systematic review methods may be useful in addressing the evidentiary needs of PHEPR practitioners and policy makers, there remains a clear need for an ongoing process that can be used to generate evidence-based PHEPR recommendations and guidelines. Given the time and resource requirements associated with conducting systematic reviews, the committee was limited to reviewing only the small selection of PHEPR practices described in Table S-1 as proof of concept. Hundreds of such reviews could be conducted to guide practitioners in operationalizing the CDC PHEPR Capabilities. Moreover, the evidence base for PHEPR practices is continually evolving with the field. As new studies and reports are published, it will be essential to have a sustained mechanism for capturing and analyzing new evidence over time and for updating prior reviews as needed. In addition to guiding PHEPR practice and decision making, such a mechanism has the potential to drive improvements in the evidence base over time and guide the research agenda through the identification of evidence gaps.

Given the complexity of the committee’s review methodology, the implications for the multidisciplinary group of experts who will need to be involved in future reviews, and the importance of practice guidelines being issued by an authoritative source with the trust of the PHEPR community and the ability to disseminate this guidance widely, the committee concludes that a centralized approach supported by CDC is the best model for a process for ongoing evidence reviews of PHEPR practices. A sustainable evidence-based review process for PHEPR practices will require organizational support and leadership; multifaceted capabilities; adequate funding; and a functional, coordinated system. The committee believes CDC should create an independent task force that would oversee methods development, topic selection, and evidence reviews; ensure appropriate external input; and generate recommendations. Importantly, as reviewers gain more experience with the evaluation of PHEPR evidence and as review methodologies continue to evolve, it will be important to assess and refine the committee’s proposed methodology to ensure that it is consistent with current review and guideline development practice and is meeting the needs of PHEPR stakeholders.

BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN PHEPR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

While there is a clear need to strengthen the evidence base for PHEPR practices through improvements in research and evaluation, an equally pressing challenge is the translation, dissemination, and implementation of the evidence to practice. It is essential for evidence-based practices to reach the hands of the policy makers and practitioners who need them most, in the most timely manner. Impediments to the uptake of evidence-based practices begin with the disconnect between PHEPR practitioners and researchers, who operate within distinct disciplines in a system that poses numerous barriers to collaboration and integration. Additional barriers include varying awareness of the existing evidence base among practitioners and a lack of guidance on how to implement evidence-based practices successfully, inadequate capacity and incentives to implement proven practices, and the failure of most studies to engage practitioners early and often. The complex nature of public health emergencies often makes it difficult to identify core practice components that are applicable across the range of such events, and additional research to identify the core components of PHEPR practices could therefore enable researchers and practitioners to better operationalize interventions in various settings. The often daunting gap between research and practice can be narrowed through such sustainable strategies and mechanisms as ensuring that research is demand-driven and training specialists in translation and implementation science, particularly for the PHEPR field. Creating a shared agenda for research and implementation is vitally important to the development and implementation of evidence-based PHEPR practices. Changes to federal programs and policy—such as asking Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreement grantees to use evidence-based practices when available and if not, to justify why, and leveraging such accreditation processes as that of the Public Health Accreditation Board—could facilitate the use of evidence-based practices by public health agencies.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

It is essential for research and continuous learning to become the expectation, not the exception, for the PHEPR field such that individuals are resourced and incentivized to conduct and participate in research, and engagement and partnerships among practitioners, communities, and researchers are promoted and maintained to build insight and trust. In short, research needs to be embedded within the PHEPR system, conducted for the PHEPR system, and applied by the PHEPR system. Grounding PHEPR practice in evidence will require transformation of both the research and practice fields. Practitioners will have to turn routinely to PHEPR research when making important decisions or implementing practices, and PHEPR researchers will have to produce research that is relevant to practitioners.

The committee is aware that the PHEPR field is relatively young and has been evolving rapidly over the past two decades. During this time, changes in policy and practice have been driven by and shaped in reaction to unexpected and often traumatic events, and rarely have been influenced by research or evidence. However, the evidence examined by the committee for this study shows a field that is maturing and will no longer be deterred by the oft-cited refrain that the relative rarity of public health emergencies prohibits the development of an evidence base for PHEPR. The nation is increasingly facing public health emergencies that present opportunities to observe and learn and conduct real-time research in order to develop a strong empirical and analytical evidence base. Most recently, the emergence of COVID-19 has highlighted critical evidence gaps and lost opportunities to expand the PHEPR evidence base. As discussed in the “Note on COVID-19” included in the Preface to this report, the COVID-19 pandemic reinforces the critical, ongoing need to have processes and programs in place to perform research and evaluation, even in real time, to better inform future decisions. Without such efforts, practitioners will continue to implement ineffective or inappropriate practices that risk wasting valuable resources and failing to protect the public’s health, and the ultimate result will be the needless loss of lives during this and future public health emergencies. As this report demonstrates, it is clear that, while challenging, strategies exist for remedying the lack of an established scientific evidence base in the PHEPR field. As the PHEPR research field continues to evolve and mature, it is the committee’s assertion that such an evidence base represents the essential foundation of future policy and practice changes.