B2

Mixed-Method Review of Activating a Public Health Emergency Operations Center

This appendix provides a detailed description of the methods for and the evidence from the mixed-method review examining the activation of a public health emergency operations center, which is summarized in Chapter 5.1

KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

Activating a public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) is a common and standard practice in response to a public health emergency. The primary question posed by the committee in this review is: “In what circumstances is activating public health emergency operations appropriate?” To further identify evidence of interest, the committee explored several sub-questions related to activation, separate public health emergency operations, changes in response, benefits and harms, and the factors that create barriers and facilitators (see Box B2-1).

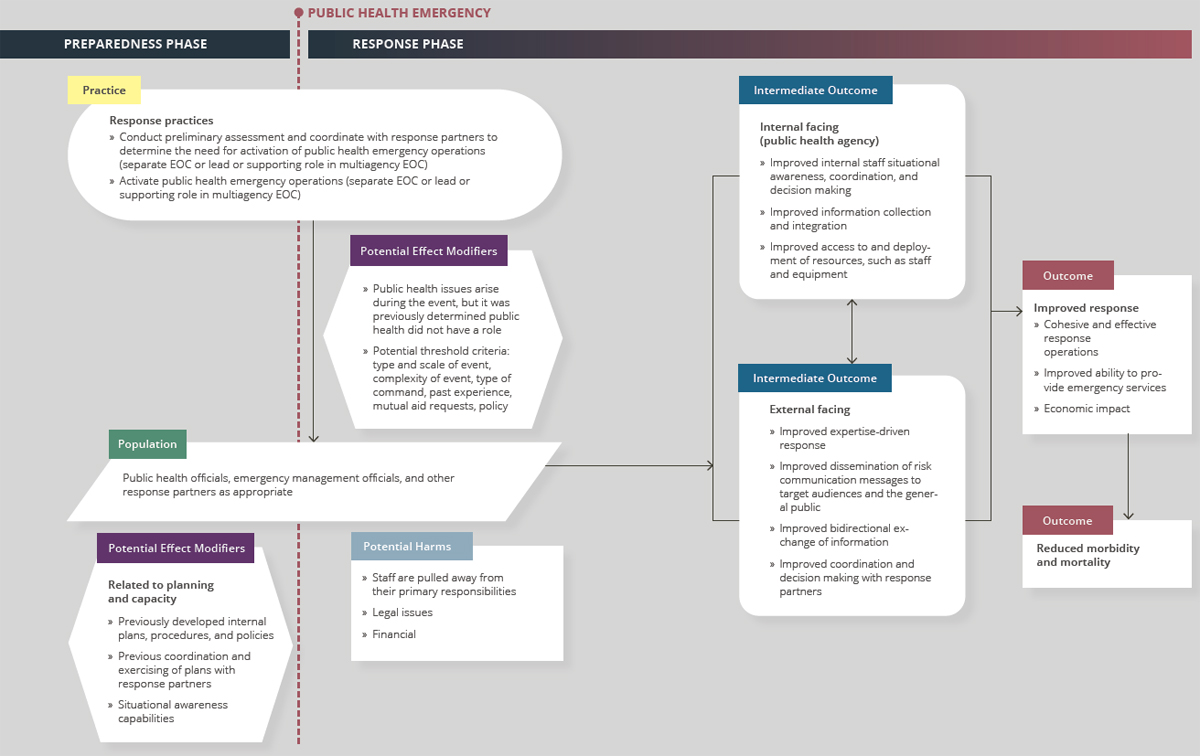

For the purposes of this review, the committee developed an analytic framework to present the causal pathway and interactions between public health emergency operations and its components, populations, and outcomes of interest (see Figure B2-1). The underlying theory is that activating a PHEOC facilitates the coordination of resources and information flow, thereby improving response efforts by increasing the efficiency and timeliness of response (see Figure B2-1).

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION

This section summarizes the evidence from the mixed-method review examining PHEOC activation. It begins with a description of the results of the literature search and then sum-

___________________

1 This section draws heavily on two reports commissioned by the committee: “Public Health Emergency Operations Coordination: Qualitative Research Evidence Synthesis” by Pradeep Sopory and Julie Novak; and “Public Health Emergency Operations Coordination: Findings from After Action Reports and Case Reports” by Sneha Patel (see Appendix C).

marizes the evidence of effectiveness. The committee considered evidence beyond effectiveness, which was compiled using an Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework encompassing balance of benefits and harms, acceptability and preferences, feasibility and public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) system considerations, resource and economic considerations, equity, and ethical considerations. The evidence from each methodological stream applicable to each of the EtD criteria is discussed; a synthesis is provided in Table B2-2 later in this appendix and in Chapter 5. Graded finding statements from evidence syntheses are italicized in the narrative below.

Full details about the study eligibility criteria, search strategy, and processes for data extraction and individual study quality assessment are available in Appendix A. Appendix C links to all of the commissioned analyses informing this review.

Results of the Literature Search

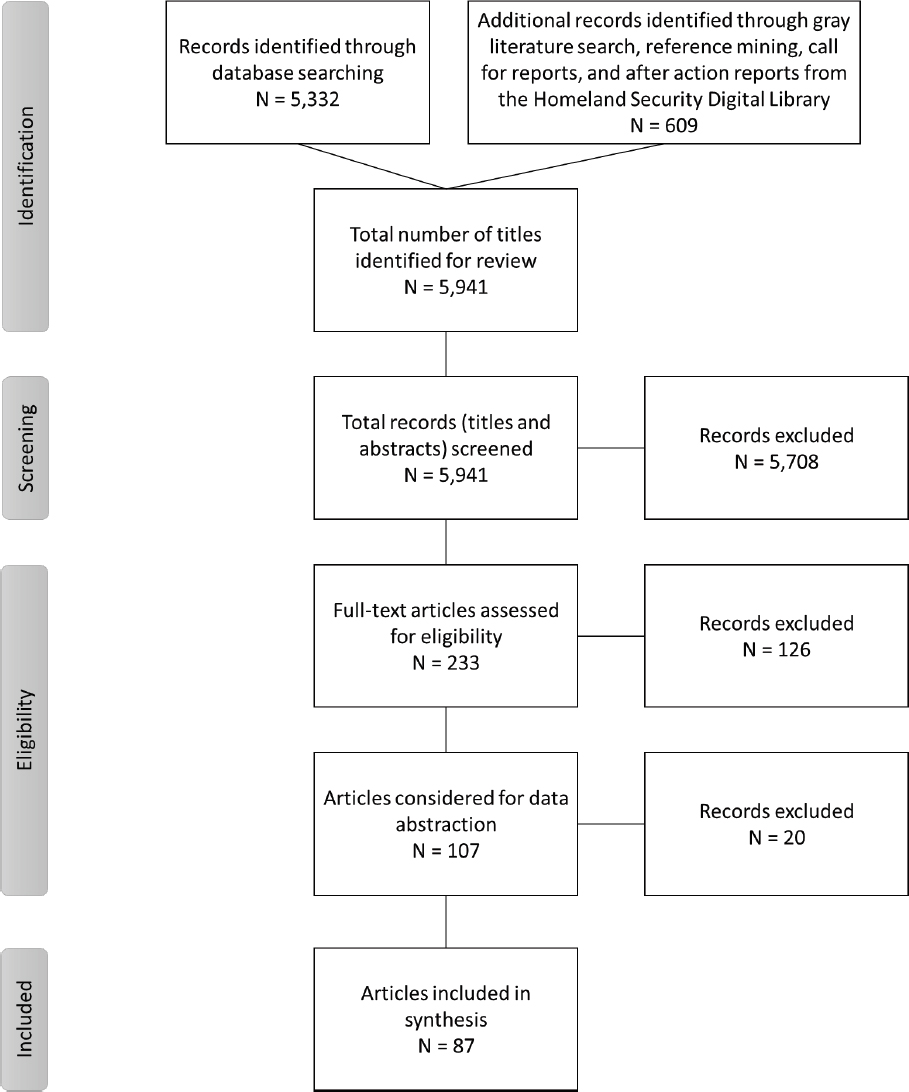

The searches of bibliographic databases (including a separate targeted search conducted through SCOPUS to identify literature in the military, first responder, and transportation disciplines) identified a total of 5,332 potentially relevant citations (deduplicated) for the mixed-method review of PHEOC activation. A search of the gray literature, reference mining, a call for reports, and a search of the Homeland Security Digital Library for after action reports (AARs) contributed an additional 609 articles. All 5,941 citations were imported into EndNote and were included in title and abstract screening. During screening, 5,708 articles were excluded because their abstracts did not appear to answer any of the key questions or they indicated that the articles were commentaries, editorials, or opinion pieces. After the abstracts had been reviewed, 233 full-text articles were reviewed and assessed for eligibility for inclusion in the mixed-method review. The committee considered 106 articles for data extraction and ultimately included 87 articles in the mixed-method review. Figure B2-2

NOTES: Arrows in the framework indicate hypothesized causal pathways between interventions and outcomes. Double-headed arrows indicate feedbac loops. EOC = emergency operations center.

| Evidence Typea | Number of Studies (as applicable)b | |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative comparative | 0 | |

| Quantitative noncomparative (postintervention measure only) | 0 | |

| Qualitative | 21 | |

| Modeling | 0 | |

| Descriptive surveys | 1 | |

| Case reports | 29c | |

| After action reports | 35c | |

| Mechanistic | N/A | |

| Parallel (systematic reviews) | N/A | |

a Evidence types are defined in Chapter 3.

b Note that sibling articles (different results from the same study published in separate articles) are counted as one study in this table. Mixed-method studies may be counted in more than one category.

c A sample of case reports and after action reports were prioritized for inclusion in this review based on relevance to the key questions, as described in Chapter 3.

1. Determining Evidence of Effect

The review identified no quantitative comparative or noncomparative studies or modeling studies eligible for inclusion, but information gleaned from the qualitative evidence synthesis and the case report and AAR evidence synthesis contributed to understanding in what circumstances activating public health emergency operations is appropriate. This is a difficult evidentiary situation; the lack of quantitative studies, in particular, speaks to the committee’s high-level finding that more and improved research is needed in this field. Still, the committee’s overriding goal was to distill the available evidence to give practitioners the best possible guidance. Therefore, the evidence gleaned was used to construct a high-level view of what happened and what appeared to work.

2. Balance of Benefits and Harms

As stated above, no research on the effectiveness of PHEOCs was identified. Therefore, findings from the qualitative evidence synthesis and the case reports and AARs evidence synthesis contributed to an understanding of the benefits and harms and undesirable effects of activating a PHEOC.

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Several qualitative studies found that staff with experience from responding to prior emergency events made faster and better decisions (presumably relative to staff without such experience), implying that this benefit becomes visible only over time in responses to future events (Bigley and Roberts 2001; Buck et al., 2006; Militello et al., 2007). Similarly, some

depicts the literature flow, indicating the number of articles included and excluded at each screening stage. Table B2-1 indicates the types of evidence included in this review.

qualitative studies found that the development of social relations and associated trust across organizations from response to a previous event became manifest in the current event in the form of smoother interorganizational coordination (Buck et al., 2006; Freedman et al., 2013).

Eight qualitative studies examined undesirable impacts associated with PHEOC activation (Bigley and Roberts 2001; Freedman et al., 2013; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Reeder and Turner, 2011; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015; Sisco et al., 2019). The qualitative evidence indicates that activation of public health emergency operations may lead to several undesirable effects, the salient of which are related to staffing deployment, staff stress and burnout, and adaptation-generated interorganizational distrust and chain-of-command disruption (high confidence in the evidence).

With regard to the benefits and harms of PHEOC activation relative to population health, the qualitative evidence generally reflects an assumption, not explicitly stated, as to the benefits of preventing morbidity and mortality in an emergency event. Qualitative studies found two sets of undesirable effects of PHEOC activation on human health: disruption of routine services that may still be needed in an emergency event (Freedman et al., 2013; Reeder and Turner, 2011), which has the potential to negatively impact public health; and negative effects on staff, such as burnout and stress (Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015). Undesirable effects of PHEOC activation on the public health system, such as staff stress and burnout, turnover among professionals, uneven distribution of staff workload, and adaptation-generated interorganizational distrust and chain-of-command disruption, were likely to be present only during the span of an event. There may, however, be situations in which these undesirable effects became embedded in the system and carry over from event to event.

Case Report and AAR Evidence Synthesis

Evidence from the case reports and AARs aligns with the qualitative evidence synthesis findings. Case reports and AARs examined in this review suggest that the efficiency of response improved following PHEOC activation. Situational awareness, interagency coordination, and information sharing were strengthened (Minnesota Department of Health, 2014; Texas Department of State Health Services, 2018; Williams et al., 2014). The timeliness of activities also improved as the result of increased availability of resources and/or capabilities for extended, expanded, or emergent responses (Williams et al., 2014). For instance, PHEOC activation during a 2002 response to West Nile virus in Arkansas led to the initiation of a public hotline to answer questions about the virus and the development of a specially designed website to provide instructions for submitting diagnostic specimens (Fleischauer et al., 2003). Findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) early response to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) show that activating the PHEOC relieved some administrative demands, which meant that the technical staff members could turn their attention to pressing public health issues (CDC, 2013).

Activation has also enabled greater access to subject-matter experts during responses with potential public health implications. During the 2010 Deepwater Horizon response, a public health unit coordinated response efforts across a multistate area of operations. The AAR states that the “formation of this unit allowed for the sharing of public health concerns, needs and requests, and thus more efficient and effective coordination of efforts” (Florida Department of Health, 2010). An unintended consequence of activation, however, was staff fatigue due to overreliance on a few key personnel or insufficient staffing depth to meet response needs.

With respect to the benefits and harms of PHEOC activation relative to system-level changes, the evidence from case reports and AARs indicates that following the decision to

activate, response operations typically became more efficient and capable of responding to emergent needs with greater flexibility because activation can result in standardized structure, greater clarity of roles, improved coordination, and sustained staffing (Boston Public Health Commission, 2013; Branum et al., 2010; CDC, 2013; Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, 2012; Iskander et al., 2017; Massachusetts Emergency Management et al., 2014; Timm and Gneuhs, 2011). Other benefits include the practical experience gained by staff under urgent and emergent conditions (Quinn et al., 2018).

3. Acceptability and Preferences

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

While the set of studies included in the qualitative evidence synthesis does not directly, or even indirectly, address the issue of acceptability and preferences, none of the articles reviewed mention any reluctance on the part of any agency to join emergency response operations for a real event or a preparedness training exercise.

Case Report and AAR Evidence Synthesis

Findings from case reports and AARs suggest that overall, the public health agency workforce values and prefers to use an incident command system (ICS) when a PHEOC is activated. Although some tension is noted with regard to shifting from day-to-day responsibilities or balancing them with response needs, public health agencies appeared to value the use of an ICS to coordinate response operations. This was evident in examples of jurisdictions that previously had not used an ICS but preferred to do so in future responses because of the structure it provides (Adams et al., 2010; Contra Costa Health Services, 2012; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2010). Findings from a case report examining CDC’s use of the ICS model during the 2009 influenza pandemic indicate that the agency preferred to modify the traditional model by including a policy unit to “guide the interpretation, coordination, and adjudication of policy during the response” (Ansell and Keller, 2014). While this is not a standard element of the ICS model, CDC found it better suited the operational context. Public health agencies could consider similar adaptations with the potential to improve public health response operations.

Descriptive Survey Study Evidence

Jensen and Youngs (Jensen, 2011; Jensen and Youngs, 2015) surveyed county emergency managers so as to describe and explain their implementation behavior with respect to the National Incident Management System (NIMS). They found that not all counties considerd NIMS to be well suited to their jurisdiction, and that those views influenced counties that modified the system and failed to implement it as designed. Likewise, Jensen and Youngs (Jensen, 2011; Jensen and Youngs, 2015) found it was critical that counties believed NIMS had the potential to solve real problems, that they perceived it to be clear and specific, that incentives and sanctions were not only provided but likely, and that capacity-building resources were provided.

4. Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Seventeen qualitative studies examined challenges to effective PHEOC activation (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Buck et al., 2006; Freedman et al., 2013; Gryth et al., 2010; Klima et al., 2012; Lis and Resnick, 2018; Mase et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Obaid et al., 2017; Reeder and Turner, 2011; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015; Shipp Hilts et al., 2016; Sisco et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2005; Yanson et al., 2017). Many of these challenges relate to general management practices, and it is important to keep in mind that typically, the opposite or absence of a barrier is a facilitator for effective operations. Challenges to effective public health emergency operations are many. Some of the most salient relate to interorganizational awareness, interorganizational relationships, interorganizational cultural differences, differences in team members’ knowledge and experience, communication technology, rules and regulations, volume of information, and lack of training (high confidence in the evidence).

Lack of interorganizational awareness—members of an operations team from an agency not being aware of other agencies (e.g., public health agencies at different levels and outside the traditional public health domain) or sometimes of other teams within their agency—was a major impediment to an effective PHEOC. This lack of awareness took the form of lack of mutual awareness of operations; lack of shared understanding of an event, particularly between organizations not familiar with each other’s domains of expertise and work practices; lack of understanding of role differences; and no common understanding of standard operating procedures among all responding organizations (Buck et al., 2006; Freedman et al., 2013; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007). Challenges involving the relationships among team members from different organizations included core members of a team from one or two organizations not interacting with other team members from different organizations; team members from one organization without prior relationships formed during training sessions with members from other organizations working independently; new members added later than others not forming relationships; mistrust between agencies and disagreement over which was in charge; a wide variety of response organizations; and different interpretations of an emergency event (Freedman et al., 2013; Lis and Resnick, 2018; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Thomas et al., 2005). Another challenge was cultural differences in organizational values of individual team members, cultures of the organizations, or organizational priorities (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Moynihan, 2008).

Communication technology also presented challenges to effective PHEOC activation. These challenges included incompatible communication systems, especially those of civil and military organizations; new technologies for emergency events that were different from those used for routine operations and therefore unfamiliar to users; system and equipment noise in communication channels; inadequate numbers of shared electronic displays; lacking or forgotten knowledge of the use of communication systems; outdated email and phone lists; problems with data entry systems and ticket and request software for interagency assistance; and radio traffic overload and lack of radio discipline (Gryth et al., 2010; Klima et al., 2012; Mase et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Reeder and Turner, 2011; Yanson et al., 2017). Also challenging was the increased volume of information to be processed and integrated resulting from a surge in phone calls, teleconferences, and emails; new, evolving issues generating new information; conflicting information and attempts to resolve it; new guidance and related information; multiple public health roles requiring different streams of information gathering and dissemination; the long duration of

an emergency event and the response; and information flow in the entire network (Chandler et al., 2016; Freedman et al., 2013; Gryth et al., 2010; Mase et al., 2017; Reeder and Turner, 2011; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015; Sisco et al., 2019).

Rules and regulations required for routine public health operations were also found to pose challenges for emergency operations. These included rules leading to bottlenecks during surge at public health laboratories; Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act rules prohibiting access to non–public health staff or secured shared data repositories on individual computers; unclear rules about overtime compensation and working at nonroutine locations; and lack of clarity of rules for information sharing, including with the media and the public (Freedman et al., 2013; Shipps Hilts et al., 2016; Sisco et al., 2019; Yanson et al., 2017).

Differences in team members’ knowledge and experience presented a further challenge to an effective PHEOC. These differences were seen in members’ willingness to enter affected areas, training in command-control environments, level of facility with tools and systems, knowledge of roles and functions, knowledge of medical procedures and equipment, and emergency operations plans (Freedman et al., 2013; Klima et al., 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015).

Case Report and AAR Evidence Synthesis

Many AARs examined for this evidence review focus on the barriers to and facilitators of successful PHEOC activation, likely because jurisdictions often use these reports to evaluate their capabilities so as to improve their response processes. Evidence from the case reports and AARs supports the above qualitative evidence with respect to barriers related to interagency relationships and coordination (Ansell and Keller, 2014; Boston Public Health Commission, 2013; Massachusetts Emergency Management et al., 2014; Moynihan, 2007; Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management, 2013; Phillips and Williamson, 2005; San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2010; Shipp Hilts et al., 2016; Texas Department of State Health Services, 2018; Wiesman et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2014); appropriate and reliable communication technology (Beatty et al., 2006; Boston Public Health Comission, 2013; Buffalo Hospital and Wright County Public Health, 2013; Chicago Department of Public Health et al., 2011; Delaware Division of Public Health, 2010; DuPage County Health Department, 2009; Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, 2012; Kilianski et al., 2014; Moynihan, 2007; Multnomah County Health Department, 2010; Redd and Frieden, 2017); lack of prior staff knowledge and experience with ICS and larger-scale disasters (Logan County Health District, 2015; Moynihan, 2007); lack of clarity with respect to roles and responsibilities (Capitol Region Council of Governments, 2016; Multnomah County Health Department, 2009; New Hampshire Department of Safety and Department of Health and Human Services, 2009a,b); lack of training on NIMS, ICS, partner roles, and job-specific roles (Augustine and Shottmer, 2005; Becker County Community Health, 2013; Boston Public Health Comission, 2013; Chicago Department of Public Health et al., 2011; Fishbane et al., 2012; Florida Department of Health, 2017; Minnesota Department of Health, 2013; Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management, 2013; Williams et al., 2014); and inadequate staffing (Boston Public Health Comission, 2013; Buehler et al., 2017; City of Nashua Department of Emergency Management, 2012; Delaware Division of Public Health, 2010; Klein et al., 2005; Multnomah County Health Department, 2009, 2010; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2010; Posid et al., 2005; Texas Department of State Health Services, 2010; Tri-County Health Department, 2017, n.d.; Wood County Health District, 2017).

Descriptive Survey Study Evidence

Further supporting the above evidence are the findings of a survey of county emergency managers conducted by Jensen and Youngs (Jensen, 2011; Jensen and Youngs, 2015) regarding the implementation of NIMS, which indicated that if interorganizational characteristics are not conducive to the implementation of emergency operations, then regardless of what jurisdictions intend, their actual implementation behavior can be negatively impacted. Additionally, when a county thought it had insufficient personnel to implement all of the components, structures, and processes of the response system, they tended to have weaker implementation intent and behavior, and vice versa.

5. Resource and Economic Considerations

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

The resource, cost, and logistical constraints of PHEOC activation are important considerations for those making the decision to activate. Fourteen qualitative studies examined the types of resources that can facilitate effective public health emergency operations (Freedman et al., 2013; Glick and Barbara, 2013; Gryth et al., 2010; Hambridge et al., 2017; Klima et al., 2012; Lis and Resnick, 2018; Lis et al., 2017; Mase et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Obaid et al., 2017; Reeder and Turner, 2011; Sisco et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2005). These studies found that resources for PHEOCs served as facilitators for effective response. They also found that the need for different types of resources and their amounts changed throughout an emergency event (Sisco et al., 2019); for example, resource needs tended to be greater in the earlier phases of an event when there was a demand surge relative to the later phases. Resources that can facilitate the effectiveness of public health emergency operations can be many. Some of the salient resources include training, databases, supplies, mechanisms for communicating with the public and media, and having a liaison or point-of-contact position. The need for various resources often changes over the course of an event (high confidence in the evidence).

Case Report and AAR Evidence Synthesis

Although the case reports and AARs reviewed do not address resources in detail, some note that activating and sustaining a response to a major public health event required large numbers of staff at various locations (Posid et al., 2005). One jurisdiction dealt with this need by formally communicating the expectation that all divisions within the public health agency were required to provide staffing resources for response efforts (Tri-County Health Department, 2013). In terms of nonhuman resources, AAR findings suggest that jurisdictions should maintain an alternative PHEOC location with the necessary communication infrastructure (Capitol Region Council of Governments, 2017). Significant resources also are required for trainings and exercises to prepare agencies for a public health emergency response. Reports reviewed indicate that such trainings and exercises were worth the time commitment and were an asset in subsequent response operations (Redd and Frieden, 2017; Wisconsin Division of Public Health, 2010). Some reports emphasize the need for continuous federal investment in public health preparedness capacity as that investment has been shown to help state and local agencies achieve federal benchmarks, carry out capacity-building activities, and develop functional capabilities (Davis et al., 2007; Wiedrich et al., 2013). The reviewed reports indicate further that risk assessments were found to be a useful means of weighing

the potential public health impacts of a resource-intensive activation against the cost implications (Quinn et al., 2018).

6. Equity

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Two qualitative studies examined the needs of at-risk populations in the context of emergency operations (Chandler et al., 2016; Sisco et al., 2019). The response to vulnerable populations is an important aspect of an effective PHEOC. Yet, pre-event planning for these operations may not always explicitly include consideration of the needs of such groups. Pre-event establishment of an interagency task force that includes community organizations to plan specifically for meeting those needs can greatly facilitate such responses (Sisco et al., 2019). Such a task force, among other things, can ensure the creation of needed databases; the provision of care in shelters, as well as staff availability for specialized services; the availability of medical equipment and medications; alternative sources of power during outages and refueling for such sources; and the availability of regular and specialized transportation (Chandler et al., 2016, Sisco et al., 2019). The response of public health emergency operations to the needs of at-risk populations can be facilitated by interagency planning that, among other things, addresses establishing a task force, creating needed databases, providing care in shelters, ensuring access to medications, dealing with power outages, and meeting transportation needs (low confidence in the evidence).

Case Report and AAR Evidence Synthesis

Few case reports and AARs address equity issues associated with PHEOC activation. Recommendations in AARs, however, suggest some consideration of equity during the planning and response phases. For instance, one report notes the inclusion of interpreters and on-site physician consultants during a mass influenza clinic (Phillips and Williamson, 2005). The inclusion of interpreters helped ensure that language barriers would not impede the provision of services. Findings from the response to the Boston Marathon bombing indicate that creating demographic profiles of health care organizations can help in understanding the unique challenges associated with particular neighborhoods and populations (Boston Public Health Commission, 2013).

Another approach highlighted in this evidence stream is including community representatives in the PHEOC for joint decision making (Wiesman et al., 2011), although it is important to ensure that these representatives are well trained in response operations. Also important is considering equity issues internal to the PHEOC. One case report briefly touches on the need to avoid gender bias in training, “given the fact that there is a much greater proportion of women within emergency relevant organizations than in emergency mission organizations” (Lutz and Lindell, 2008). Additional research is needed to better understand how biases or inequities internal to a PHEOC relate to equitable response outcomes.

7. Ethical Considerations2

The section on equity above addresses ethical considerations in PHEOC operations related to the principle of justice or fairness. In addition, the primary ethical principle underlying the initiation of a PHEOC is that of stewardship of limited resources. This principle, often framed as a duty to produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people as efficiently as possible, is seen as particularly important during public health emergencies, when resources typically are limited and need to be allocated with care. As a result, ethical concerns with respect to implementing a PHEOC are centered primarily on the pragmatic benefits and harms of doing so—namely, the possibility that implementing a PHEOC will waste resources and generate harms through the neglect of other programs while team members are reassigned to PHEOC operations. Some of the procedural principles in play can include transparency, which is supported when a PHEOC improves communication; and proportionality (acting only in proportion to need, or using the least restrictive means to achieve a desired outcome), which is supported when having an activated PHEOC improves situational awareness and therefore averts unnecessary implementation of interventions.

TABLE B2-2 Evidence to Decision Summary Table for Activation of Public Health Emergency Operations

| In what circumstances is activating public health emergency operations appropriate? | |

|---|---|

| Balance of Benefits and Harms No quantitative research on the effectiveness of public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) activation was identified. The evidence from qualitative studies and from case reports and after action reports (AARs) indicates that activation generally results in more efficient response operations and improved ability to respond to emergent needs with greater flexibility, and as a result may have implicit benefits in relation to improving population health during a public health emergency. The timeliness of response activities also improves because of the increased availability of resources and/or capabilities. Moreover, activation may enable greater access to subject-matter experts during responses with potential public health implications. A long-term benefit of activation is the accumulation of institutional knowledge of what does and does not work (i.e., practical experience) gained by the public health agency under urgent or emergent conditions. Important factors in deciding whether activating a PHEOC will lead to any harms include the potential need for more intensive staffing due to long hours and the need to continue routine public health services, as well as the potential for adaptation-generated interorganizational distrust and chain-of-command disruption. These harms are likely to be present only during an event and not to persist postevent for any appreciable length of time. In some cases, however, such harms may become embedded in the public health system and carry over from event to event (e.g., if a negative interpersonal relationship forms that creates barriers to future successful collaboration). Simply activating a PHEOC is not a comprehensive solution; public health agencies must be ready to manage them effectively, and without that readiness, more harms may be experienced. |

Sources of Evidence

|

___________________

2 Ethical considerations included in this section were generated through committee discussions, drawing on the ethical principles laid out in Box 3-4 in Chapter 3 and key ethics and policy texts, including the 2009 Institute of Medicine letter report on crisis standards of care (IOM, 2009), the 2008 CDC white paper “Ethical Guidance for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response: Highlighting Ethics and Values in a Vital Public Health Service” (Jennings and Arras, 2008), Emergency Ethics: Public Health Preparedness and Response (Jennings et al., 2016), and The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics (Mastroianni et al., 2019).

| Acceptability and Preferences Public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) practitioners generally find their roles in participating in emergency operations acceptable and are amenable to the resulting changes in work patterns. PHEPR practitioners prefer to use an incident command system (ICS) but appreciate the ability to modify the structure to better suit their operational context and jurisdiction. Furthermore, to facilitate the implementation of public health emergency operations, practitioners must believe that implementation of the National Incident Management System (NIMS)/ICS has the potential to solve real problems and is clear and specific, that incentives and sanctions are not only provided but likely, and that capacity-building resources are being provided. Ongoing support for meaningful work is important, and PHEOCs that provide this support are therefore likely to be more successful. |

Sources of Evidence

|

| Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations Many barriers impact the feasibility of successful PHEOC activation, and these barriers are often related to challenges involving general management practices. These challenges include interorganizational awareness, relationships, and cultural differences; differences in team members’ knowledge and experience; adequate staffing to implement the activation with all of its components, structures, and processes; communication technology; rules and regulations; the volume of information; and a lack of training in NIMS/ICS, partner roles, and job-specific roles. If these interorganizational characteristics are not conducive to implementation, actual implementation behavior can be negatively impacted regardless of what jurisdictions intend. |

Sources of Evidence

|

| Resource and Economic Considerations The resource, cost, and logistical constraints of PHEOC activation are important considerations in deciding whether to activate. These considerations often change over the course of an event and may be sizable depending on the scope of the event. Salient resources include training; databases; supplies; and mechanism(s) for communicating with the public and media, among which is the creation of liaison or point-of-contact positions. These resource needs may dictate the level at which the public health emergency operations should be coordinated (e.g., local, regional, state, and/or national). Baseline PHEOC operations require an infusion of resources beyond normal operations, in general, and public health agencies need to be prepared to manage those costs, ideally with support from other levels of government. |

Sources of Evidence

|

| Equity Inequities in the implementation of public health emergency operations for different populations due to variability in the availability of resources, infrastructure, and funding likely exist among state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies (and are also related to the resource and economic considerations discussed above). Activating a PHEOC can help ensure that the needs of particular at-risk populations are addressed during the response to an event. Accomplishing this requires interagency planning based within the PHEOC that entails establishing a task force to help these population(s), creating a database to collect relevant risk information, providing targeted care in shelters, ensuring access to medications, and addressing specific medical needs caused by power outages and unique transportation requirements. Another approach involves welcoming community representatives into the PHEOC for more inclusive decision making. Additional research is needed to better understand how biases or inequities internal to a PHEOC relate to equitable response outcomes. PHEOCs likely reflect the implicit biases of their decision makers and will support equity more or less well based on the perspective of those individuals. |

Sources of Evidence

|

| Ethical Considerations The section on equity above addresses ethical considerations in a PHEOC related to the principle of justice or fairness. In addition, the primary ethical principle underlying the initiation of a PHEOC is that of stewardship of limited resources. This principle, often framed as a duty to produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people as efficiently as possible, is frequently seen as particularly important during public health emergencies, since resources in emergencies are typically limited and need to be allocated with care. As a result, ethical concerns related to implementing a PHEOC are centered primarily on the pragmatic benefits and harms of doing so: namely, the possibility that implementing a PHEOC will waste resources and generate harms due to the neglect of other programs while team members are reassigned to PHEOC operations. Some of the procedural principles in play can include transparency, which is supported when a PHEOC improves communication, and proportionality (acting only in proportion to need, or using the least restrictive means to achieve a desired outcome), which is supported when having an activated PHEOC improves situational awareness and therefore averts unnecessary implementation of interventions. |

Source of Evidence

|

|

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The following considerations for implementation were drawn from the synthesis of qualitative research studies, the synthesis of case reports and AARs, and descriptive surveys.

8. Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Seven qualitative studies report on factors in determining when to activate a PHEOC (Freedman et al., 2013; Glick and Barbara, 2013; Lis and Resnick, 2018; Lis et al., 2017; Obaid et al., 2017; Sisco et al., 2019; Yanson et al., 2017). The qualitative evidence indicates that public health emergency operations are fully activated, as support or lead, when an emergency event is large in size and complex in scope, or when the hazards it poses impact primarily or only human health as opposed to natural or built environments, as is the case, for example, with disease outbreaks. The activation may also include activation of a liaison officer and may precede the onset of an event through advance activation of interagency protocols and memorandums of understanding. Overall aspects of activation include determination of specific thresholds for activation and time to the activation decision (moderate confidence in the evidence).

As noted above, the scope of an emergency event is associated with the activation of a PHEOC. Measures of scope include the depletion of resources and the imposition of a high burden on operations, used to create a threshold for determining whether public health emergency operations should be activated. Determination of the critical point or specific threshold that elicits an activation decision is thus an essential aspect of activation. Findings from health care settings are informative in this regard. For example, an emergency event can lead to a surge in demand for health care services. Standards of care fall on a continuum ranging from conventional to contingency to crisis care. The triggers and indicators that signal the need to transition to crisis standards of care are characterized by insufficient resources to meet the increased demand for care during an emergency event (Lis et al., 2017). Five factors have been found to influence the time taken to activate a PHEOC: previous knowledge and

experience; the degree to which an emergency event is atypical; the amount, speed, and quality of situation data available; integration of the data to build a picture of the situation; and the perception of urgency to make a decision (Glick and Barbara, 2013).

Case Report and AAR Evidence Synthesis

Findings from the case reports and AARs reviewed support the above qualitative evidence, suggesting that it was helpful to activate for more complex and multijurisdictional responses that presented threats to public health and to do so early, even if the event’s size and scope were initially unknown (Cruz et al., 2015). There was often a period of initial uncertainty as to the need to activate, particularly regarding exposure to infectious and novel diseases (Cole et al., 2015). New Hampshire was able to respond successfully to a 2012 Nor’easter, for example, because the state activated an ICS ahead of the storm and prepared to respond to a winter weather emergency even though it was predicted to be an average snowstorm. The advance decision to activate allowed for rapid escalation of response operations when needed (City of Nashua Department of Emergency Management, 2012). Other case reports and AARs show that as the demands of an incident extended beyond the capacity of existing resources, activating an ICS enabled an effective surge in capacity (County of San Diego, 2018; Wiedrich et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2014). A typical example is a 2017 hepatitis A outbreak in San Diego during which the number of cases continued to rise, leading to the need for additional vaccination, sanitation, and education measures (County of San Diego, 2018).

The case reports and AARs also reveal that activation triggers were useful in determining when to activate, reactivate, or deactivate response operations. During disease outbreaks, use of the number of cases as a trigger informed the decision to activate and the level at which to do so (Williams et al., 2014). It is important to note that while triggers have been defined in advance of an event, novel diseases have required the development of new triggers, as was the case when CDC developed new triggers for activating a PHEOC for MERS-CoV given the uncertainty of the epidemiology of the disease. Findings from the case reports and AARs indicate further that it is best for predefined triggers to remain flexible, as the adequacy of resources to meet response needs at a given time also plays an important role in the decision to activate. It may be useful as well to consider having flexible triggers at the local level that do not necessarily rely on a state’s declaration of an emergency, as response needs can overburden local resources even in the absence of a formal state emergency declaration. Additionally, as was learned from New Hampshire’s 2009 H1N1 response, it can be helpful to define standardized triggers among response agencies for physical activation of a regional multiagency coordinating entity (MACE) location (New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2009a). Some regions had physically opened a MACE, whereas others simply had one person answering phone calls and sending emails for activation, resulting in a disconnect between state and local expectations for the response.

Findings from the case reports and AARs indicate that local public health agencies activated and benefited from activating PHEOCs to lead local responses to a public health emergency (Branum et al., 2010; Porter et al., 2011). Activation allowed local jurisdictions to keep pace with the response and improved interagency coordination if other agencies were involved (Capitol Region Council of Governments, 2016; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2010). Activation at the local level was also found to be beneficial in support of reponse to state-level public health threats (New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2010). A recurring issue raised in AARs is the need to clarify the role of state versus local

PHEOCs (New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2009b, 2010; Ohio Department of Health, 2010; Texas Department of State Health Services, 2010, 2018). Noted as particularly important is ensuring clear chains of command and decision-making authority during a response. Regardless of the structure established, public health agencies across levels could thereby better integrate their functions.

Public health agencies led multiagency EOCs in response to public health threats (e.g., infectious disease outbreaks) when coordination and information sharing among response agencies were critical to meeting objectives, a finding that supports those from the qualitative evidence synthesis. Activation helped clarify roles among the supporting response agencies (e.g., emergency management, police, fire, school officials). Numerous AARs and case reports also describe the benefits of public health support functions during planned events or incidents with potential for public health implications (Boston Public Health Commission, 2013; Buehler et al., 2017; Capitol Region Council of Governments, 2016, 2017; Contra Costa Health Services, 2012; Fleischauer et al., 2003; Florida Department of Health, 2010; Hunter et al., 2012; Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency et al., 2014; Wisconsin Division of Public Health, 2010). During the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, for instance, public health agencies helped facilitate family reunification (Boston Public Health Commission, 2013). During a 2011 tsunami threat in California, public health agencies “activated surveillance and epidemiology, environmental health and mental health and psychological support functions” (Hunter et al., 2012). Public health agencies also participated in mass care and the management and distribution of medical supplies. AARs on environmental disasters with the potential for short- and/or long-term public health impacts (e.g., oil spills, refinery fires) likewise note the importance of including public health in multiagency activations.

9. Other Implementation Considerations

The following conceptual findings inform the perspectives and approaches one should consider when implementing a PHEOC.

Leverage Strong, Decisive Leadership and Create Shared Understanding in Response

Qualitative evidence synthesis

Nine qualitative studies examined the use of mental models in public health emergency operations (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Glick and Barbara, 2013; Gryth et al., 2010; Lis et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015; Sisco et al., 2019). According to these studies, knowledge of different aspects of public health emergency operations, including situational awareness of an event, is cognitively represented through mental models, and building this knowledge base, especially the situational awareness of an event, is critical to emergency operations. When leaders and staff of public health and other agencies undergo preparedness training for an emergency event or act as “eyes and ears” for monitoring of an ongoing event, they are, in fact, creating cognitive representations of the event in the form of mental models. The full representation of all aspects of an event may be within the mind of one leader, although more often, understanding of the different aspects of an event is distributed across multiple leaders and staff (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Moynihan, 2008; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015). These mental models evolve, and for some people, they may initially be incorrect (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Gryth et al., 2010). Therefore, one way to think about coordination among members of a group involved in emergency operations is to view it as coordination of the varying mental models held by staff and leaders within

and across agencies. Mental models may serve as the basis for activation decisions. Leaders and commanders rarely have all available information about an ongoing event, but experienced personnel often make rapid decisions based on their mental models of prior events (Glick and Barbara, 2013; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015). Effective coordination of emergency operations depends to some extent on the degree to which accurate mental models are shared among members of the groups involved, leading to a shared understanding of an emergency event, as well as of interagency functions (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Sisco et al., 2019). Knowledge of different aspects of public health emergency operations, and especially situational awareness of ongoing events, can be seen as cognitively constituted through mental models that are distributed across leaders and staff and that may be based on less-than-complete information. Viewing shared understanding of public health emergency operations overall in terms of mental models can help in understanding the functioning of activation and coordination activities (moderate confidence in the evidence).

Case report and AAR evidence synthesis

Case reports and AARs implicitly highlight the need for strong leadership willing to be decisive despite uncertainties inherent in emergencies. Leaders need to have the ability to receive new, sometimes unexpected information and to revise objectives as necessary (Redd and Frieden, 2017). Leaders also need to work to promote trust by creating a shared sense of purpose and recognizing the contributions of different network members (Moynihan, 2007).

Ensure Simultaneous Rigidity and Flexibility in a PHEOC

Qualitative evidence synthesis

Seven qualitative studies examined simultaneously ensuring rigidity and flexibility in a PHEOC (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Buck et al., 2006; Chandler et al., 2016; Freedman et al., 2013; Hambridge et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Moynihan, 2008). PHEOCs may be characterized only in terms of their rigid command and control structures, with the potential flexibility of the operations being downplayed. A more accurate overall conceptualization, however, is that these operations entail both command and control functions and preplanned adjustments and ad hoc improvisations (Chandler et al., 2016; Freedman et al., 2013; Hambridge et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Moynihan, 2008). The often changing, complex, and dynamic environment of an emergency event generates unique demands to which available command and control procedures do not fully apply, necessitating the emergence of new organizational structures and responses (Buck et al., 2006; Chandler et al., 2016; Freedman et al., 2013). Formal structures may be reconfigured through such strategies as structure elaboration, role switching, and authority migration so as to enhance organizational flexibility and thus reliability (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; McMaster and Baber, 2012). Similarly, professionals, especially those with experience, may not follow established procedures strictly, but make adjustments and use creative problem solving as required to respond to an evolving event (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Freedman et al., 2013; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015). Emergency operations can be conceptualized and operationalized not just as rigid command and control functions but also as flexible adaptations and improvisations. Taking both perspectives on public health emergency operations can help in designing effective activation and coordination activities (high confidence in the evidence).

Case report and AAR evidence synthesis

While indicating that flexibility is crucial, case reports and AARs also stress the importance of adhering to basic principles. While juris-

dictions acknowledged the value of an ICS, lack of adherence to basic principles also led to inefficiencies in some instances. For example, the lack of incident action plans (IAPs), response objectives, and routine briefings was reported to hinder response operations (Florida Department of Health, 2010, 2017; Metropolitan Medical Response System, 2016; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2009b; Ohio Department of Health, 2010). Likewise, the absence of routine updates to the incident commander inhibited well-informed and timely decision making (Logan County Health District, 2015), and an ongoing lack of communication through the chain of command led to delayed emergency notification and mutual aid and impeded timely resource requests (Lyons et al., 2009). Conversely, the inclusion of operations briefings, debriefs, situational reports (SitReps) and IAPs with response objectives, and job action sheets contributed to the success of response (Boston Public Health Comission, 2013; Capitol Region Council of Governments, 2016; Florida Department of Health, 2017; Logan County Health District, 2015; New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Safety, 2009b; San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2010).

View Public Health Emergency Operations Teams as Social Groups

Qualitative evidence synthesis

Seven qualitative studies examined viewing public health emergency operations teams as social groups (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Buck et al., 2006; Freedman et al., 2013; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007; Moynihan, 2008; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015). To take this view is to acknowledge that these teams are likely to face issues of differing values, power struggles, and political machinations (Bigley and Roberts, 2001). Also recognized are cultural differences among staff from different organizational cultures, such as those that are strictly hierarchical versus those that value judgment and discretion (Moynihan, 2008), as well as preexisting social power differentials and economic and political interests in the impacted communities during the response and recovery phases of an emergency event (Buck et al., 2006). Recognized as well are issues of affect and emotion, such as fear and concern about personal safety among staff members. Once these intensely social phenomena have been acknowledged, they can be dealt with productively, thereby improving the functioning of emergency operations (Buck et al., 2006; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015). Seeing work teams as social groups improves their functioning in other ways as well. Pre-event training across agencies creates informal relationships and a sense of social closeness and collegiality, which in turn fosters creativity and adaptation in response activities, trust, cohesion, and shared goals linked inextricably to the development of social relations and group formation (Buck et al., 2006; Freedman et al., 2013; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Militello et al., 2007). Public health emergency operations teams, especially those involving multiple agencies, can be viewed as social groups in their functioning. A history of informal social relationships through prior training leads to familiarity and trust across differences in organizational cultures that can reduce power struggles and political maneuvering and enhance cooperation and coordination (moderate confidence in the evidence).

Understand How Response Changes Following PHEOC Activation

Qualitative evidence synthesis

Five qualitative studies examined how response changes following PHEOC activation (Chandler et al., 2016; Lis et al., 2017; McMaster and Baber, 2012; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015; Sisco et al., 2019). Studies considered several typologies for understanding these changes, but the changes are best described in terms of the Dynes typology, which can be used to classify responses into four categories: established organized

response (regular old-task structural arrangements), expanding organized response (regular new-task structural arrangements), extending organized response (nonregular old-task structural arrangements), and emergent organized response (nonregular new-task structural arrangements) (Chandler et al., 2016; Dynes, 1993, 1994). This typology helps clarify how public health agencies navigate their responses by carrying out both regular and irregular tasks while also functioning within both old and new structural arrangements. Response changes can be judged in terms of their adaptation to the emergency event as a deviation from the planned, established responses. At a minimum, response changes can be seen as exhibiting no, some, or a great deal of adaptation, depending on the phase of the emergency event, with a great deal of adaptation being most likely in the event’s earliest phases (McMaster and Baber, 2012; Rimstad and Sollid, 2015; Sisco et al., 2019). Response changes following activation of public health emergency operations can be seen in terms of the degree of adaptation (none, some, a great deal) of established responses. The type of response change may depend on the phase of the emergency event (high confidence in the evidence).

Leverage Staff with Past Response Experiences

Case report and AAR evidence synthesis

Case reports and AARs indicate that lessons learned from decisions not to activate a PHEOC during previous events influenced decisions to activate during subsequent public health emergencies (Adams et al., 2010; Wiedrich et al., 2013). In 1999, for instance, Nassau County, New York, decided not to activate in response to West Nile virus, a new disease of unknown magnitude (Adams et al., 2010). In 2008, however, when the threat reemerged, the decision to activate was made, given the complexities involved and the recognized need for resources. Thus, looking to past experience can be a practical means of determining whether to activate.

Furthermore, staff’s level of familiarity with the ICS model represented either a barrier to or facilitator of successful response operations. Numerous AARs indicate that the previous knowledge and experience of staff enabled positive outcomes (Moynihan, 2007; Quinn et al., 2018; San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2010; Wisconsin Division of Public Health, 2010), whereas a lack of familiarity with ICS or limited experience with larger-scale disasters was a barrier to effective response operations (Logan County Health District, 2015; Moynihan, 2007). In some instances, the use of experienced staff and subject-matter experts early on in the response to a novel outbreak is recommended (Multnomah County Health Department, 2010), although overreliance on a few key personnel can lead to staff fatigue (Delaware Division of Public Health, 2010).

REFERENCES FOR ARTICLES INCLUDED IN THE MIXED-METHOD REVIEW

Qualitative Studies

Bigley, G. A., and K. H. Roberts. 2001. The incident command system: High-reliability organizing for complex and volatile task environments. Academy of Management Journal 44(6):1281–1299.

Buck, D. A., J. E. Trainor, and B. E. Aguirre. 2006. A critical evaluation of the incident command system and NIMS. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 3(3).

Chandler, T., D. M. Abramson, B. Panigrahi, J. Schlegelmilch, and N. Frye. 2016. Crisis decision-making during Hurricane Sandy: An analysis of established and emergent disaster response behaviors in the New York Metro Area. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 10(3):436–442.

Freedman, A. M., M. Mindlin, C. Morley, M. Griffin, W. Wooten, and K. Miner. 2013. Addressing the gap between public health emergency planning and incident response lessons learned from the 2009 H1N1 outbreak in San Diego County. Disaster Health 1(1):13–20.

Glick, J. A., and J. A. Barbara. 2013. Moving from situational awareness to decisions during disaster response: Transition to decision making. Journal of Emergency Management 11(6):423–432.

Gryth, D., M. Radestad, H. Nilsson, O. Nerf, L. Svensson, M. Castren, and A. Ruter. 2010. Evaluation of medical command and control using performance indicators in a full-scale, major aircraft accident exercise. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine 25(2):118–123.

Hambridge, N. B., A. M. Howitt, and D. W. Giles. 2017. Coordination in crises: Implementation of the national incident management system by surface transportation agencies. Homeland Security Affairs 13.

Klima, D. A., S. H. Seiler, J. B. Peterson, A. B. Christmas, J. M. Green, G. Fleming, M. H. Thomason, and R. F. Sing. 2012. Full-scale regional exercises: Closing the gaps in disaster preparedness. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 73(3):592–597; discussion 597–598.

Lis, R., and A. T. Resnick. 2018. Coordinated communications and decision making to support a regional severe infectious disease response. Health Security 16(3):158–164.

Lis, R., V. Sakata, and O. Lien. 2017. How to choose? Using the Delphi method to develop consensus triggers and indicators for disaster response. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 11(4):467–472.

Mase, W. A., B. Bickford, C. L. Thomas, S. D. Jones, and M. Bisesi. 2017. After-action review of the 2009-10 H1N1 influenza outbreak response: Ohio’s public health system’s performance. Journal of Emergency Management 15(5):325–334.

McMaster, R., and C. Baber. 2012. Multi-agency operations: Cooperation during flooding. Applied Ergonomics 43(1):38–47.

Militello, L. G., E. S. Patterson, L. Bowman, and R. Wears. 2007. Information flow during crisis management: Challenges to coordination in the emergency operations center. Cognition, Technology and Work 9(1):25–31.

Moynihan, D. P. 2008. Combining structural forms in the search for policy tools: Incident command systems in U.S. crisis management. Governance 21(2):205–229.

Obaid, J. M., G. Bailey, H. Wheeler, L. Meyers, S. J. Medcalf, K. F. Hansen, K. K. Sanger, and J. J. Lowe. 2017. Utilization of functional exercises to build regional emergency preparedness among rural health organizations in the U.S. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine 32(2):224–230.

Reeder, B., and A. M. Turner. 2011. Scenario-based design: A method for connecting information system design with public health operations and emergency management. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 44(6):978–988.

Rimstad, R., and S. J. M. Sollid. 2015. A retrospective observational study of medical incident command and decision-making in the 2011 Oslo bombing. International Journal of Emergency Medicine 8(1):1–10.

Shipp Hilts, A., S. Mack, M. Eidson, T. Nguyen, and G. S. Birkhead. 2016. New York State public health system response to Hurricane Sandy: Lessons from the field. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 10(3):443–453.

Sisco, S., E. M. A. Jones, E. K. Giebelhaus, T. Hadi, I. Gonzalez, and F. Lee Kahn. 2019. The role and function of the liaison officer: Lessons learned and applied after Superstorm Sandy. Health Security 17(2):109–116.

Thomas, T. L., E. B. Hsu, H. K. Kim, S. Colli, G. Arana, and G. B. Green. 2005. The incident command system in disasters: Evaluation methods for a hospital-based exercise. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine 20(1):14–23.

Yanson, A., A. S. Hilts, S. Mack, M. Eidson, T. Nguyen, and G. Birkhead. 2017. Superstorm Sandy: Emergency management staff perceptions of impact and recommendations for future preparedness, New York State. Journal of Emergency Management 15(4):209–218.

Descriptive Survey Studies

Jensen, J. 2011. The current NIMS implementation behavior of United States counties. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 8.

Jensen, J., and G. Youngs. 2015. Explaining implementation behaviour of the National Incident Management System (NIMS). Disasters 39(2):362–388.

Case Reports

Adams, E. H., E. Scanlon, J. J. Callahan, 3rd, and M. T. Carney. 2010. Utilization of an incident command system for a public health threat: West Nile virus in Nassau County, New York, 2008. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 16(4):309–315.

Ansell, C., and A. Keller. 2014. Adapting the incident command model for knowledge-based crises: The case of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government.

Augustine, J., and J. T. Schoettmer. 2005. Evacuation of a rural community hospital: Lessons learned from an unplanned event. Disaster Management & Response 3(3):68–72.

Beatty, M. E., S. Phelps, M. C. Rohner, and M. I. Weisfuse. 2006. Blackout of 2003: Public health effects and emergency response. Public Health Reports 121(1):36–44.

Branum, A., J. E. Dietz, and D. R. Black. 2010. An evaluation of local incident command system personnel in a pandemic influenza. Journal of Emergency Management. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2010.0031.

Buehler, J. W., J. Caum, and S. J. Alles. 2017. Public health and the Pope’s visit to Philadelphia, 2015. Health Security 15(5):548–558.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2013. CDC’s emergency management program activities—Worldwide, 2003–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(35):709–713.

Cole, D., M. Peninger, S. Singh, J. Tucker, C. Douglas, and S. Kiernan. 2015. Measles emergency response: Lessons learned from a measles exposure in an 800-bed facility. American Journal of Infection Control 43(6 Suppl 1):S14–S15.

Cruz, M. A., N. M. Hawk, C. Poulet, J. Rovira, and E. N. Rouse. 2015. Public health incident management: Logistical and operational aspects of the 2009 initial outbreak of H1N1 influenza in Mexico. American Journal of Disaster Medicine 10(4):347–353.

Davis, M. V., P. D. MacDonald, J. S. Cline, and E. L. Baker. 2007. Evaluation of public health response to hurricanes finds North Carolina better prepared for public health emergencies. Public Health Reports 122(1):17–26.

Fishbane, M., A. Kist, and R. A. Schieber. 2012. Use of the emergency incident command system for school-located mass influenza vaccination clinics. Pediatrics 129(Suppl 2):S101–S106.

Fleischauer, A. T., S. Williams, D. R. O’Leary, T. McChesney, W. Mason, S. Falk, L. Gladden, S. Snow, F. L. Clark, P. Terebuh, and F. W. Boozman. 2003. The West Nile virus epidemic in Arkansas, 2002: The Arkansas Department of Health Response. Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 100(3):94–99.

Hunter, J. C., A. W. Crawley, M. Petrie, J. E. Yang, and T. J. Aragón. 2012. Local public health system response to the tsunami threat in coastal California following the Tohoku earthquake. PLOS Currents 2012(4). http://doi.org/10.1371/4f7f57285b804.

Iskander, J., D. A. Rose, and N. D. Ghiya. 2017. Science in emergency response at CDC: Structure and functions. American Journal of Public Health 107(S2):S122–S125.

Kilianski, A., A. T. O’Rourke, C. L. Carlson, S. M. Parikh, and F. Shipman-Amuwo. 2014. The planning, execution, and evaluation of a mass prophylaxis full-scale exercise in Cook County, IL. Biosecurity & Bioterrorism 12(2):106–116.

Klein, K. R., M. S. Rosenthal, and H. A. Klausner. 2005. Blackout 2003: Preparedness and lessons learned from the perspectives of four hospitals. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine 20(5):343–349.

Lutz, L. D., and M. K. Lindell. 2008. Incident command system as a response model within emergency operation centers during Hurricane Rita. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 16(3):122–134.

Lyons, W. H., F. M. Burkle, Jr., D. L. Roepke, and J. E. Bertz. 2009. An influenza pandemic exercise in a major urban setting, part I: Hospital health systems lessons learned and implications for future planning. American Journal of Disaster Medicine 4(2):120–128.

Moynihan, D. P. 2007. From forest fires to Hurricane Katrina: Case studies of incident command systems. Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government.

Phillips, F. B., and J. P. Williamson. 2005. Local health department applies incident management system for successful mass influenza clinics. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice 11(4):269–273.

Porter, D., M. Hall, B. Hartl, C. Raevsky, R. Peacock, D. Kraker, S. Walls, and G. Brink. 2011. Local health department 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination clinics—CDC staffing model comparison and other best practices. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice 17(6):530–533.

Posid, J. M., S. M. Bruce, J. T. Guarnizo, M. L. Taylor, and B. W. Garza. 2005. SARS: Mobilizing and maintaining a public health emergency response. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 11(3):208–215.

Quinn, E., T. Johnstone, Z. Najjar, T. Cains, G. Tan, E. Huhtinen, S. Nilsson, S. Burgess, M. Dunn, and L. Gupta. 2018. Lessons learned from implementing an incident command system during a local multiagency response to a legionnaires’ disease cluster in Sydney, NSW. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 12(4):539–542.

Redd, S. C., and T. R. Frieden. 2017. CDC’s evolving approach to emergency response. Health Security 15(1):41–52.

Shipp Hilts, A., S. Mack, M. Eidson, T. Nguyen, and G. S. Birkhead. 2016. New York State public health system response to Hurricane Sandy: An analysis of emergency reports. Disaster Medicine & Public Health Preparedness 10(3):308–313.

Timm, N. L., and M. Gneuhs. 2011. The pediatric hospital incident command system: An innovative approach to hospital emergency management. Journal of Trauma—Injury, Infection and Critical Care 71(5 Suppl 2):S549–S554.

Wiedrich, T. W., J. L. Sickler, B. L. Vossler, and S. P. Pickard. 2013. Critical systems for public health management of floods, North Dakota. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice 19(3):259–265.

Wiesman, J., A. Melnick, J. Bright, C. Carreon, K. Richards, J. Sherrill, and J. Vines. 2011. Lessons learned from a policy decision to coordinate a multijurisdiction H1N1 response with a single incident management team. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice 17(1):28–35.

Williams, H. A., R. L. Dunville, S. I. Gerber, D. D. Erdman, N. Pesik, D. Kuhar, et al. 2014. CDC’s early response to a novel viral disease, middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), September 2012–May 2014. Public Health Reports 130(4):307–317.

AARs3

Becker County Community Health. 2013. People & Stuff 2013—HSEM Region 3 logistics exercise after action report/improvement plan. Becker County, MN. December 6, 2013.

Boston Public Health Commission. 2013. 2013 Boston Marathon emergency support function F8 (ESF-8) public health and medical planning, response, and recovery operations (April 15–April 16). https://delvalle.bphc.org/mod/wiki/view.php?pageid=63 (accessed April 3, 2020).

Buffalo Hospital and Wright County Public Health. 2013. Buffalo hospital closed pod after-action report/improvement plan. Buffalo, NY. November 21, 2013.

Capitol Region Council of Governments. 2016. Ebola virus disease functional exercise after action report. Hartford, CT. May 18, 2016.

Capitol Region Council of Governments. 2017. Ebola Virus Disease Full Scale Exercise After Action Report. Hartford, CT. May 19, 2017.

Chicago Department of Public Health, Illinois Department of Public Health, and Metropolitan Chicago Healthcare Council. 2011. Illinois hospitals pediatric full-scale exercise after action report. Chicago, IL. May 21, 2011.

City of Nashua Department of Emergency Management. 2012. October Nor’easter after action report. Nashua, NH. March 2, 2012.

Contra Costa Health Services. 2012. Chevron Richmond refinery fire of August 6, 2012: After action report based on medical/health debriefing. Martinez, CA. December 6, 2012.

County of San Diego. 2018. Hepatitis A outbreak after action report. May 2018. San Diego, CA. https://www.sandiegocounty.gov/content/dam/sdc/cosd/SanDiegoHepatitisAOutbreak-2017-18-AfterActionReport.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

Delaware Division of Public Health. 2010. Novel H1N1 influenza Delaware response April 2009 to March 2010: After action report/improvement plan. Dover, DE. June 1, 2010. https://dhss.delaware.gov/DHSS/DPH/php/files/h1n1aar.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

DuPage County Health Department. 2009. 00.10 H1N1 after action report (AAR)—improvement plan (IP). Wheaton, IL. April 26, 2009–May 11, 2009.

Florida Department of Health. 2010. 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill response: ESF 8 after action report and improvement plan. Tallahassee, FL. April 30, 2011. http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/emergency-preparedness-and-response/training-exercise/_documents/deepwater-aar.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

Florida Department of Health. 2017. 2017 statewide hurricane full scale exercise. Tallahassee, FL. September 19, 2017. http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/emergency-preparedness-and-response/trainingexercise/_documents/2017-statewide-hurricane-fse.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

Governor’s Office of Homeland Security & Emergency Preparedness. 2012. Hurricane Isaac after action report & improvement plan. Baton Rouge, LA. December 31, 2012.

Logan County Health District. 2015. Logan County Health District 2015 full scale exercise. Bellefontaine, OH. June 9–10, 2015. http://loganhealth.org/documents/2015LCHDAARfinaldraft_06_24_2015.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, City of Boston, City of Cambridge, Town of Watertown, Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Transit Police Department, and M. S. P. Massachusetts National Guard. 2014. After action report for the response to the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings. https://www.policefoundation.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/05/after-action-report-for-the-response-to-the-2013-boston-marathon-bombings_0.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

Metropolitan Medical Response System. 2016. CT region 3 ESF-8 Ebola preparedness & response: After action report. Falls Church, VA. October 29, 2015.

Minnesota Department of Health. 2013. Operation Loon Call 2013: After-action report/improvement plan. St. Paul, MN. June 11, 2013.

___________________

3 These AARs were retrieved from the Homeland Security Digital Library at https://www.hsdl.org/c (accessed June 10, 2020); they may be accessed and downloaded there.

Minnesota Department of Health. 2014. DOC FE flash floods 2014: After-action report/improvement plan 2014. St. Paul, MN. May 29, 2014.

Multnomah County Health Department. 2009. “Swine flu Multco” Spring 2009 H1N1 response of April 27–May 12, 2009: After action report/improvement plan. Portland, OR. December 28, 2009.

Multnomah County Health Department. 2010. H1N1 Fall 2009–Multco Aug 4–5, 2009–December 8, 2009: After action report/improvement plan. Portland, OR. May 4, 2010.

New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and New Hampshire Department of Safety. 2009a. 2009 spring H1N1 response: After action report/improvement plan. Concord, NH. September 22, 2009.

New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and New Hampshire Department of Safety. 2009b. Cities ready initiative operation rapid RX full-scale exercise: After action report. Concord, NH. October 16, 17, 24, 2009.

New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services and New Hampshire Department of Safety. 2010. New Hampshire July 1, 2009–March 30, 2010 H1N1 response: After action report/improvement plan. Concord, NH.

Ohio Department of Health. 2010. Fall 2009 H1N1 response: ICS operations conducted through September 21, 2009–Febuary 4, 2010: After action report—Improvement plan. Columbus, OH. June 29, 2010.

Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management. 2013. Earth, wind, and fire 2013: After-action report/corrective action plan. Oklahoma City, OK. November 14, 2013.

San Francisco Department of Public Health. 2010. Fall/winter 2009–2010 H1N1 swine flu response: San Francisco, California: September 28, 2009–March 9,2010: After action report/improvement plan. August 20, 2010. https://www.sfcdcp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/H1N1-AAR-Executive-Summary.Fall-Winter-2009-2010-id639.pdf (accessed January 23, 2020).

Texas Department of State Health Services. 2010. Texas Department of State Health Services response to the novel H1N1 pandemic influenza (2009 and 2010): After action report. The Litaker Group LLC. Austin, TX. August 30, 2010.

Texas Department of State Health Services. 2018. Hurricane Harvey response: After-action report. Austin, TX. May 30, 2018.

Tri-County Health Department. 2013. PHIMT NACCHO model practice award application. Greenwood Village, CO.

Tri-County Health Department. 2017. Public health emergency dispensing exercise (PHEDX) after action report and improvement plan. Greenwood Village, CO. June 15–17, 2017.

Tri-County Health Department. n.d. Public health incident management team (PHIMT). Greenwood Village, CO.

Wisconsin Division of Public Health. 2010. 2009 H1N1 influenza response after action report and improvement plan. Madison, WI. July 2010.

Wisconsin Hospital Emergency Preparedness Program. 2010. After action report (AAR) for H1N1 influenza. Madison, WI. April 24, 2009–Spring 2010.

Wood County Health District. 2017. 2017 regional functional/full-scale exercise: After-action report/improvement plan. Bowling Green, OH. June 12, 2017.

Ethics and Policy Text

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Guidance for establishing crisis standards of care for use in disaster situations: A letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Jennings, B. and J. Arras. 2008. Ethical guidance for public health emergency preparedness and response: Highlighting ethics and values in a vital public health service. https://www.cdc.gov/od/science/integrity/phethics/docs/white_paper_final_for_website_2012_4_6_12_final_for_web_508_compliant.pdf (accessed February 23, 2020).

Jennings, B., J. D. Arras, D. H. Barrett, and B. A. Ellis. 2016. Emergency ethics: Public health preparedness and response. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mastroianni, A. C., J. P. Kahn, and N. E. Kass, eds. 2019. The Oxford handbook of public health ethics. New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190245191.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190245191 (accessed June 3, 2020).

ARTICLES NOT FORMALLY INCLUDED IN THE MIXED-METHOD REVIEW

Dynes, R. R. 1993. Disaster reduction: The importance of adequate assumptions about social organization. Sociological Spectrum 13:175–192.

Dynes, R. R. 1994. Community emergency planning: False assumptions and inappropriate analogies. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 12:141–158.