1

Advancing Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response System Capabilities to Respond to Increasing Threats

Communities across the nation are increasingly facing complex public health emergencies. State, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies play a vital role in protecting and securing the nation’s health. These agencies routinely make difficult decisions on the front lines of emergency response and recovery and must be prepared to respond effectively to diverse public health threats, including infectious diseases, natural disasters, and human-made events. Yet, little concerted effort has been made to establish a scientific evidence base to guide and inform the actions of SLTT public health agencies, and public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) practitioners in particular. The PHEPR field consequently has been based largely on long-standing rather than evidence-based practice.

PHEPR practitioners require knowledge of evidence-based practices to make effective decisions regarding strategies to mitigate the impact of public health emergencies on the public’s health and to save lives. As the nation approaches two decades since September 11, 2001, this is an opportune time to take stock of the state of the evidence on PHEPR practices and the improvements necessary to move the field forward and to strengthen the PHEPR system. Without efforts to synthesize and evaluate PHEPR research in a coherent, transparent, and rigorous manner, practitioners will continue to implement ineffective or inappropriate practices that waste valuable resources and fail to protect the public’s health, researchers will continue to face difficulty in identifying critical research gaps, and funders will continue to be challenged by deciding where to focus their resources. The PHEPR field needs to be informed by and grounded in robust evidence for what works, where, why, and for whom. This report documents the results of a study undertaken to examine the actions, opportunities, and resources necessary to achieve this vision.

This chapter presents the study charge, the study committee’s conceptual framework for a complex PHEPR system, and the underlying reasons for the current state of the PHEPR evidence base, and explains the importance of a process for the development of evidence-based PHEPR guidelines. It concludes with an overview of the report.

STUDY CHARGE

Recognizing that the research in the PHEPR field has not been synthesized and evaluated in a coherent manner and seeking to ensure the development of an evidence-based culture within the PHEPR field, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) charged the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine with developing the methodology for and subsequently conducting a systematic review and evaluation1 of the evidence for PHEPR practices. The committee was also charged with providing recommendations for future research needed to address critical gaps in evidence-based PHEPR practices, as well as processes needed to improve the overall quality of evidence within the field. The full charge to the committee is presented in Box 1-1. To respond to this charge, the National Academies convened a 20-member ad hoc committee comprised of experts in the fields of PHEPR practice, PHEPR research, quantitative and qualitative evidence review methodology, operations and systems research, and ethics. Biographies of the committee members are presented in Appendix F.

___________________

1 Although the term “comprehensive review” was used in the committee’s Statement of Task (see Box 1-1), the committee uses the field-accepted term “systematic review” throughout this report. The committee applied a mixed-method approach to its systematic review.

- Identify research regarding preparedness and response practices within the prioritized PHEPR Capabilities and functions, and apply the committee’s evidence review methodology to assess the quality of and summarize the body of evidence regarding effectiveness of these practices;

- Develop recommendations for preparedness and response practices within the prioritized areas that communities and state, territorial, local, and/or tribal agencies should or should not adopt, based on evidence demonstrating the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of those practices; and

- Provide recommendations for future research needed to address critical gaps in evidence-based preparedness and response practices, including, as appropriate, additional research on promising but not yet proven practices within the prioritized PHEPR Capabilities and functions, as well as processes needed to improve the overall quality of evidence within the field.

Literature regarding preparedness practices will be included for evaluation only to the extent that there is a measurable and explicit connection to response practices, as determined by the committee. Literature regarding recovery practices is not within the scope of this study, except in the event where initial recovery practices are unable to be distinguished from response practices. Literature regarding practices specific to the Hospital Preparedness Program will also be excluded from this study; however, areas where public health and health care delivery functions intersect may be included as appropriate.

CONCEPTUALIZING THE COMPLEX PHEPR SYSTEM

The Building Blocks of the PHEPR System

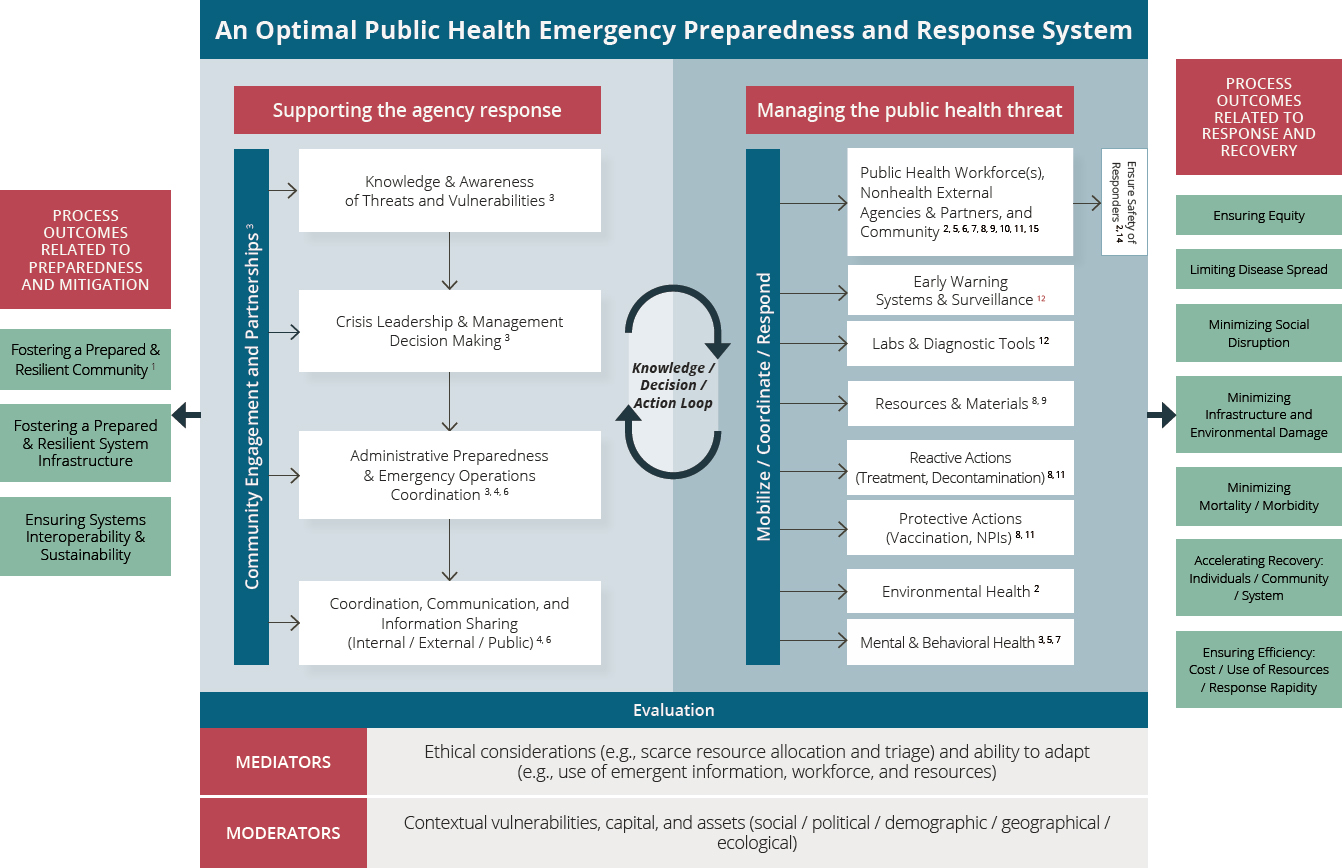

The PHEPR system, with its multifaceted mission to prevent, protect against, quickly respond to, and recover from public health emergencies, is inherently complex, encompassing policies, organizations, and programs (Nelson et al., 2007b). To guide the committee’s approach to its task and ground the committee’s thinking about the PHEPR system as a whole, the committee developed a conceptual framework to explore the complexity and various interdependencies of the current PHEPR system (see Figure 1-1).

Since 2011, 15 foundational capabilities set forth by CDC have guided public health agencies in assessing, building, and sustaining PHEPR capacity (CDC, 2018). Before 2011, there were no standards to guide the PHEPR work of public health agencies. These 15 capabilities, updated in 2018, are defined in the agency’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public Health (PHEPR Capabilities) (CDC, 2018; Martinez et al., 2019) (see Box 1-2). While the committee was charged with reviewing the evidence for practices specifically encompassed within the PHEPR Capabilities, this report is designed to be useful to those who have roles in PHEPR but are guided by different doctrines, such as first responders, health care stakeholders, and emergency management professionals.

NOTE: The numbers shown on the figure denote the pertinent PHEPR Capabilities:

- Community Preparedness

- Community Recovery

- Emergency Operations Coordination

- Emergency Public Information and Warning

- Fatality Management

- Information Sharing

- Mass Care

- Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration

- Medical Materiel Management and Distribution

- Medical Surge

- Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs)

- Public Health Laboratory Testing

- Public Health Surveillance and Epidemiological Investigation

- Responder Safety and Health

- Volunteer Management

| BOX 1-2 | PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE CAPABILITIES: NATIONAL STANDARDS FOR STATE, LOCAL, TRIBAL, AND TERRITORIAL PUBLIC HEALTH |

The public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) Capabilities are a set of 15 distinct yet interrelated capability standards designed to advance the emergency preparedness and response capacity of state and local public health systems. The PHEPR Capabilities are organized into six domains and two tiers. Tier 1 capability standards form the foundation of PHEPR, and Tier 2 capability standards are cross-cutting. Each capability standard is comprised of functions, and each function encompasses specific tasks that are supported by resource elements.

Community Resilience

- Capability 1 – Community Preparedness (Tier 1)

- Capability 2 – Community Recovery (Tier 2)

Incident Management

- Capability 3 – Emergency Operations Coordination (Tier 1)

Information Management

- Capability 4 – Emergency Public Information and Warning (Tier 1)

- Capability 6 – Information Sharing (Tier 1)

Countermeasures and Mitigation

- Capability 8 – Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration (Tier 1)

- Capability 9 – Medical Materiel Management and Distribution (Tier 1)

- Capability 11 – Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (Tier 2)

- Capability 15 – Responder Safety and Health (Tier 1)

Surge Management

- Capability 5 – Fatality Management (Tier 2)

- Capability 7 – Mass Care (Tier 2)

- Capability 10 – Medical Surge (Tier 2)

- Capability 14 – Volunteer Management (Tier 2)

Biosurveillance

- Capability 12 – Public Health Laboratory Testing (Tier 1)

- Capability 13 – Public Health Surveillance and Epidemiological Investigation (Tier 1)

SOURCE: Excerpted from CDC, 2018.

The PHEPR Capabilities alone do not constitute the PHEPR system; rather, the system comprises the interactions among the Capabilities and the context in which they are operationalized. To develop a deeper understanding of how the PHEPR Capabilities relate to each other and to various contextual factors and interact within the complex PHEPR system, the committee conducted a search for a framework that would help visualize these relationships and interactions. Previous logic models have been developed to depict various aspects of PHEPR (CDC, 2019b; Gibson et al., 2012; Stoto et al., 2017), but these models were inadequate to capture the interconnectedness and complexity of the PHEPR system. More recently, Khan and colleagues (2018) took a complex adaptive systems approach in developing a framework to represent the essential elements and interactions between these

elements for a resilient public health system. While overlap exists between some of the structural elements identified in the Khan and colleagues framework and the PHEPR Capabilities (e.g., surveillance and monitoring), the committee was interested in a framework that could encompass structure, function, context, and outcomes simultaneously. To address this gap, the committee developed the framework depicted in Figure 1-1.2

The committee’s framework is intended to depict an adaptable and scalable PHEPR system. The framework illustrates how the PHEPR Capabilities (denoted throughout the system) fit into a larger system of governmental and nongovernmental actors. The inner rectangle of the framework represents the formal PHEPR system, and is divided into two domains: “supporting the agency response,” which captures the organizational features that ought to be present among responding entities; and “managing the public health threat,” which identifies the practices that may be employed to respond to an event. Each domain influences the other, as indicated by the knowledge, decision, and action loop between them. The framework reinforces that leadership, management, and critical decision making are essential to the optimal operation of a PHEPR system. To the extent possible, strategic and tactical decisions should be governed by evidence and thoughtfulness and built on a robust evidence base.

Each side of the framework yields important preparedness and response outcomes for the PHEPR system. Underlying the framework are system mediators and moderators that account for the various contextual factors that may influence the execution of PHEPR practices. Thus, the committee’s conceptual framework highlights how the components of the PHEPR system are intertwined. Understanding these linkages among actors, actions, and the PHEPR Capabilities is critical to informing how certain practices may interact and affect other practices and outcomes. A PHEPR research enterprise would consider how the system as a whole achieves its desired outcomes, such as equitable response, rapid recovery, and minimized harms, in addition to considering the extent to which each Capability contributes to that outcome. In addition, in viewing the committee’s conceptual framework, it is important to understand the more general and fundamental characteristics that influence how systems work (see Box 1-3).

The PHEPR system consists of a multiplicity of actors from SLTT and federal response systems and organizations, including those responsible for public health, emergency management, public safety, and health care delivery, as well as other governmental and nongovernmental organizations (IOM, 2008). The committee views the PHEPR system (and this framework) as a system nested within many integrated, larger systems. Although different sectors will frequently work in isolation, their interconnectivity is often amplified during a public health emergency. Linkov and colleagues (2014) describe how management strategies for one network (e.g., telecommunications, water, gas, transportation) may be dependent on the functionality of another. Understanding in advance of an event how these different systems will affect one another can save time and effort during the response and recovery phases, and enables researchers and practitioners to consider the trade-offs inherent in operational decisions made in the midst of an event and under conditions of uncertainty.

___________________

2 The committee developed the conceptual framework for an optimal PHEPR system through a consensus process and based on the expert opinion of the committee members. It was intended as a heuristic device to help the committee conceptualize the systemic (interdependent) nature of the PHEPR system, and to consider the pathways through which PHEPR Capabilities may be associated with system-level outcomes. Fundamentally, it is a framing device.

| BOX 1-3 | COMMON SYSTEM CHARACTERISTICS |

- Self-organizing—system dynamics arise spontaneously from internal structure

- Constantly changing—systems adjust and readjust at many interactive timescales

- Tightly linked—the high degree of connectivity means that change in one sub-system affects the others

- Governed by feedback—a positive or negative response that may alter the intervention or expected effects

- Nonlinear—relationships within a system cannot be arranged along a simple input–output line

- History dependent—short-term effects of intervening may differ from long-term effects

- Counterintuitive—cause and effect are often distant in time and space, defying solutions that pit causes close to the effects they seek to address

- Resistant to change—seemingly obvious solutions may fail or worsen the situation

SOURCE: Excerpted from WHO, 2009.

Defining a PHEPR Practice

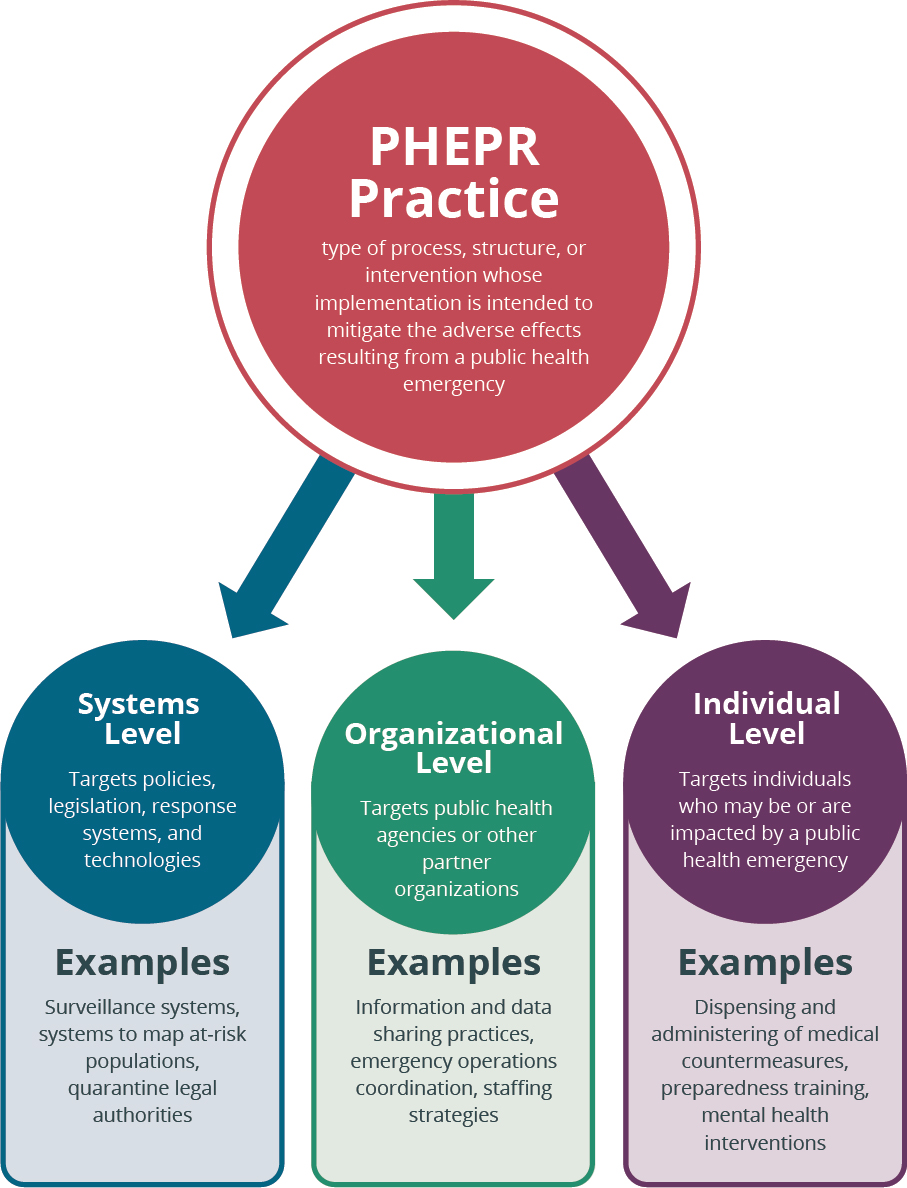

In PHEPR, there is seldom a discrete “intervention” as there is in clinical medicine; therefore, the committee defined a PHEPR practice broadly as a type of process, structure, or intervention whose implementation is intended to mitigate the adverse effects of a public health emergency on the population as a whole or a particular sub-group within the population. Given the heterogeneity, complexity, and multicomponent nature of many PHEPR practices, the committee categorized PHEPR practices based on whether they target the individual and community, organizational, or systems level (see Figure 1-2). In addition to targeting multiple levels, PHEPR practices can be strategic (e.g., long-term planning), tactical (e.g., workflow planning), or operational (e.g., real-time intervention) and be implemented by different public health agencies (federal, SLTT).

- PHEPR practices may be aimed at individuals through emergency risk communication efforts, dispensing and administering of medical countermeasures, preparedness education and training initiatives, and mental health interventions during emergencies.

- PHEPR practices may be aimed at the organizational level through information and data sharing and situational awareness practices, administrative preparedness practices, emergency operations coordination, modules and programs for training and exercising staff, and strategies to ensure a fully staffed response.

- PHEPR practices may be aimed at the systems level through the conduct of jurisdictional risk assessments; mapping of the locations of at-risk populations; surveillance systems; and policies related to funding, staffing, and resources.

Consistent with the charge shown in Box 1-1, the committee took as its starting point for identifying PHEPR practices the 15 PHEPR Capabilities (see Box 1-2). CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public Health does not define PHEPR practices per se. Instead, each

___________________

4 Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act. Public Law 116-22, 116th Cong. (January 3, 2019).

Capability standard comprises Capability “functions” that must occur to achieve the standard. Specific “tasks” (or action steps) are identified for each function. The committee considered whether the Capability functions and/or tasks translated well to the concept of a PHEPR practice with the level of specificity for which an evidence review could be conducted. In many (but not all) cases, the Capability functions were too broad and the tasks too tactical to be appropriate for such a review. For example, a function within the Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) Capability is “Implement nonpharmaceutical interventions,” and a task is “Implement NPIs in designated locations” (CDC, 2018). As the effectiveness of different NPIs is likely to differ, a specific NPI would need to be identified as the PHEPR practice to be reviewed. Ultimately, the committee developed a comprehensive list of potential PHEPR practices that was generated by breaking down the functions and tasks within the PHEPR Capabilities into topics at a level of resolution for which conclusions about effectiveness could potentially be drawn.3

UNDERLYING REASONS FOR THE CURRENT STATE OF THE PHEPR EVIDENCE BASE

Since the events of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent anthrax events, PHEPR practitioners have responded to countless emergencies, and the United States has invested billions of dollars and immense amounts of human capital to develop and enhance PHEPR infrastructure, systems, and science (Watson et al., 2017). These research investments, however, have been skewed toward more traditional biomedical research, such as the research and development of medical countermeasures for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear emergencies. For example, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provides $1.6 to $1.8 billion per year in funding for basic and applied research to support the development of medical countermeasures (Watson et al., 2017). However, there has been no equivalent investment in research to examine how to improve the epidemiology of biological incidents, communicate the risks, manage the distribution of medical countermeasures, or mitigate long-term consequences. Total 10-year research funding levels (2008–2017) for the Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration Capability was estimated at just over $100,000 (Keim et al., 2019). This imbalance creates significant challenges for effective response by PHEPR practitioners.

The modern PHEPR research enterprise can be traced back to the CDC-funded Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs) and the Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers (PERLCs). The PERRCs and the PERLCs represented the first and only major federal investment in public health systems research aimed at addressing PHEPR knowledge gaps (Savoia et al., 2018). In 2006, the Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA)4 articulated the need to define the existing knowledge base and establish a research agenda for PHEPR. Therefore, at the request of CDC, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a letter report in 2008 identifying four near-term priority research areas for PHEPR: (1) enhancing the usefulness of training, (2) improving timely emergency communications, (3) creating and maintaining sustainable response systems, and (4) generating effectiveness criteria and metrics (IOM, 2008). Guided by PAHPA and the 2008 IOM letter report on PHEPR research priorities, CDC invested $57 million in research grants through

___________________

3 The comprehensive list of potential PHEPR practices is included in the commissioned paper documenting the scoping review, titled “Review and Evidence Mapping of Scholarly Publications Within CDC’s 15 Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities,” by Testa and colleagues (see Appendix D).

the PERRCs and $34 million in grants for workforce preparedness development through the PERLCs (Maddock et al., 2018; Qari et al., 2018). In addition to CDC, many other federal research programs made investments in PHEPR research in the years following September 11, 2001. The evolution of the PHEPR research field is discussed further in Chapter 2.

Despite past investments in PHEPR research, however, it has repeatedly been observed that the PHEPR evidence base is not proportionate to the considerable human and financial investments made in better preparing the nation for public health emergencies, and furthermore, that it is overly reliant on anecdotal and descriptive reports or studies with limited validity and generalizability (Carbone and Thomas, 2018; Khan et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2008; Siegfried et al., 2017). Acosta and colleagues (2009) note a lack of cumulative knowledge across the field because very few studies have developed and tested clear hypotheses based on existing evidence. Several aspects of the current PHEPR field, detailed below, help explain why the development of a robust evidence base for PHEPR practices has been challenging:

- a rapidly evolving PHEPR system,

- the increasing complexity of public health emergencies and the PHEPR system,

- methodological challenges for PHEPR research,

- a poorly organized approach to PHEPR research and implications for the PHEPR researcher pipeline, and

- a well-documented gap between PHEPR research and practice.

A Rapidly Evolving PHEPR System

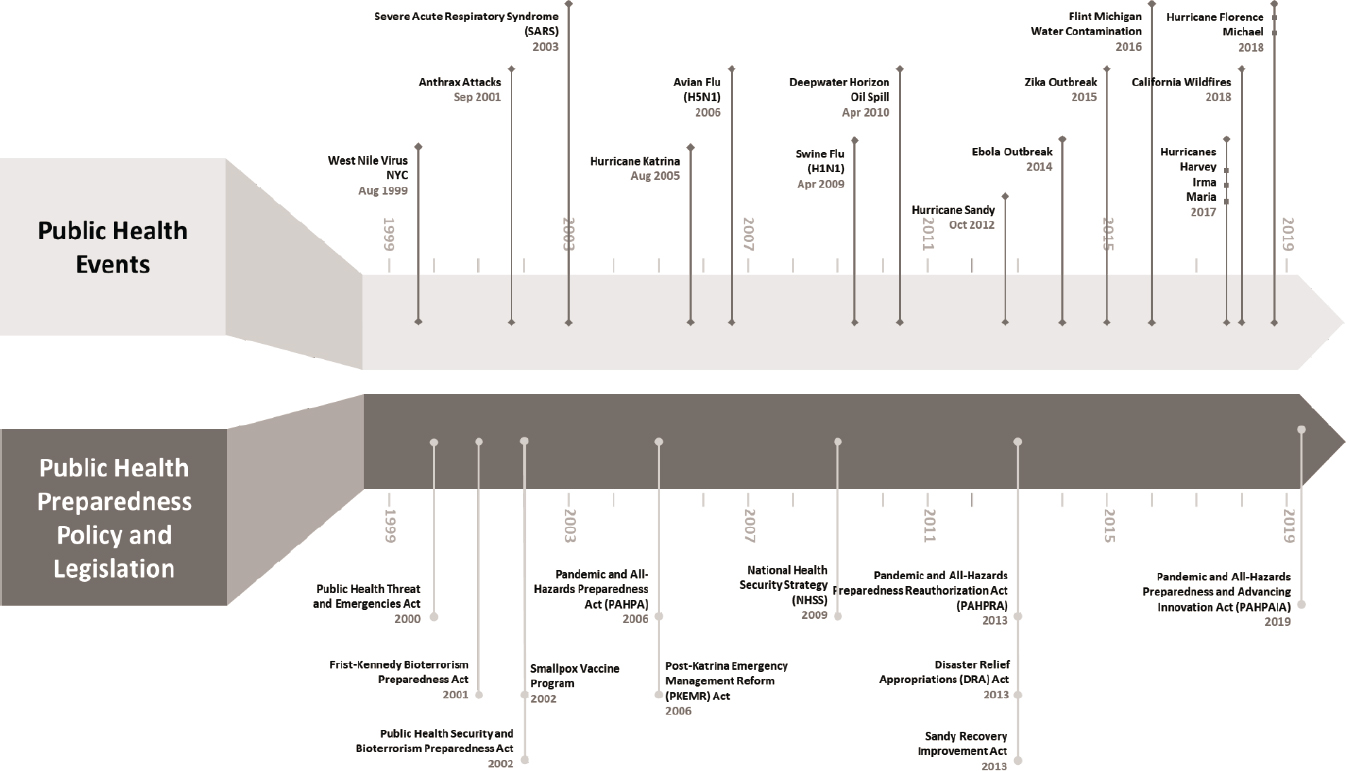

PHEPR is a relatively young field that has evolved rapidly over the past two decades. Immediately following the 2001 anthrax events, Congress and the executive branch rapidly and collaboratively developed legislation, Presidential Directives, and appropriations that shaped the modern PHEPR system (see Figure 1-3). The trajectory of funding sources and mechanisms has had a dramatic effect on both the scope of and infrastructure for PHEPR (Horney et al., 2019). During this time, changes in policy and practice have been driven more by reactions to public health emergencies (such as the 2001 anthrax attacks and the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]) than by systematic primary research.

Although Congress has passed several forms of supporting legislation, the largest health-focused program since 2002 is CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) Cooperative Agreement, which allocates federal funds to each state, the four largest U.S. cities, and eight U.S. territories and freely associated states for a total of 62 awardees nationwide (CDC, 2020). The 15 PHEPR Capabilities provide the framework for all PHEP program recipients, and PHEP recipients are required to build or sustain the elements identified in Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public Health (CDC, 2019b). Similarly, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services oversees the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP), which supports regional health care system preparedness and provides funding for health care coalitions (ASPR, 2019). The HPP is also guided by a set of specific capabilities (ASPR, 2016). While the PHEP Cooperative Agreement and HPP have been instrumental in the development of preparedness and response capacity for many jurisdictions, the past two decades have seen the emergence of additional initiatives and agencies that also have influenced the PHEPR system, including the following:

- CDC’s Cities Readiness Initiative (CRI)—a federally funded program designed to enhance preparedness in the nation’s largest population centers. State and large metropolitan public health departments use CRI funding to develop, test, and maintain plans for quickly receiving medical countermeasures from the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) (see below) and distribute them to local communities (CDC, 2019a).

- ASPR’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority—established to support the transition of medical countermeasures (e.g., vaccines, drugs, diagnostics) from research through advanced development toward consideration for approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and incorporation into the SNS (HHS, 2020).

- The SNS—established to hold the nation’s supply of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies for use in a public health emergency when local supplies are exhausted and SLTT responders request federal assistance to support their response efforts (HHS, 2019b).

- The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP)—established to support the building, sustainment, and delivery of core capabilities essential to achieving the National Preparedness Goal of a secure and resilient nation. HSGP comprises three programs—the State Homeland Security Program, the Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI), and Operation Stonegarden (FEMA, 2020).

Initially, planning in PHEPR followed a pattern whereby SLTT public health agencies received overall guidance and direction from CDC to develop disease-specific plans. These plans included wide-area anthrax release response plans (2001), followed by smallpox plans (2002), SARS plans (2003), pandemic influenza plans (2004), Ebola response plans (2013). The PHEPR system was also heavily influenced by principles and practices from other disciplines, such as emergency management and public safety (Rose et al., 2017). Adding to the challenge was expansion of the roles and expectations of public health workers to include emergency response (VanDevanter et al., 2010). In an effort to introduce some standardization and fundamental expectations, CDC developed the PHEPR Capabilities in 2011 (updated in 2018) to help guide SLTT preparedness and response planning. Even as the PHEPR system has matured, however, determining how to implement the practices that fall within these overarching Capabilities effectively continues to be an iterative and challenging process.

The structure of funding for the PHEPR system and the funding reductions that have occurred over the years have created challenges for SLTT public health agencies in developing and maintaining the workforce and capacity to implement PHEPR practices, as well as for the monitoring and evaluation of implemented practices (Watson et al., 2017). Funding streams typically have been siloed with respect to their priorities or their targeted end users and focused on a singular disease or planning function, hampering collaboration across sectors and actors. Moreover, legislation and funding typically reflect or respond to the most recent past events, and this reactive prioritization has resulted in planning efforts that fit the needs of the last disaster rather than those of the underlying system.

Conclusion: A PHEPR system based on discrete, reactive funding streams will fail to meet the critical needs of advancing the development and use of evidence to optimize public health emergency response. As the PHEPR research field continues to evolve and mature, the committee asserts that a rigorous evidence base is the crucial foundation for future changes in policy and practice.

The Increasing Complexity of Public Health Emergencies and the PHEPR System

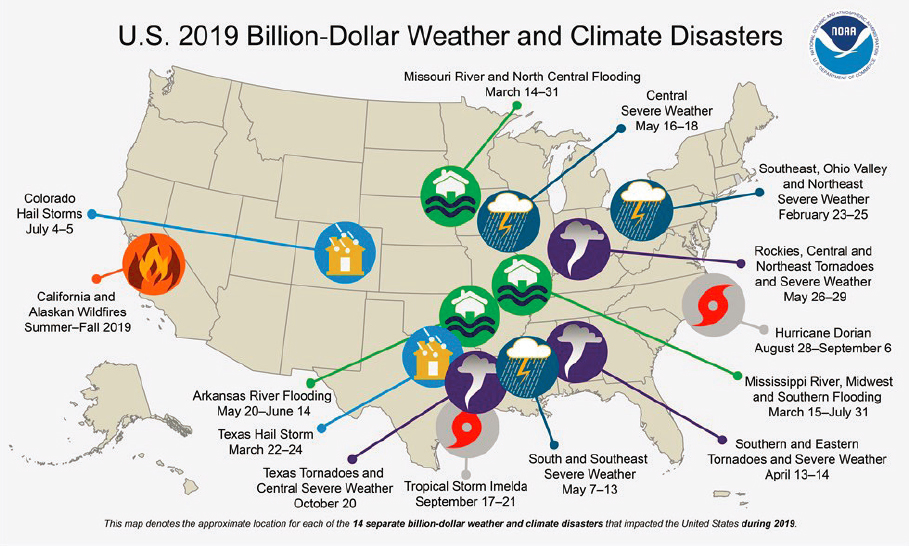

The knowledge gaps and paucity of high-quality evidence that currently characterize PHEPR reflect in part the inherent complexity of the PHEPR system (see Figure 1-1 earlier in this chapter) and the complexity of PHEPR practices themselves. PHEPR practices feature multiple interacting components that target multiple levels (e.g., individual and community, organizational, and systems), are implemented with an array of other practices (both public health oriented and non–health related), and often require tailoring to local conditions. Lastly, and perhaps most important, contextual factors are creating an increasingly intense and diverse threat environment (HHS, 2019a). Such factors as global migration, accelerating population density, increased proportions of unvaccinated individuals, and climate change are increasing the number, severity, and complexity of public health emergencies. In 2019 alone, 14 weather and climate disaster events resulting in losses of more than $1 billion each occurred across the United States (see Figure 1-4).

At the same time, the increased use of and dependence on technologies and the interconnectedness of supply chains mean that even local public health emergencies can have global consequences (Bunnell et al., 2019). Thus, the systemic complexities of PHEPR cannot be addressed in isolation, but are always affected by (and affecting) the broader global risk environment. Conducting research on the highly complex PHEPR system in the context of an increasingly complex environment, with many unknown public health threats, will require a comprehensive approach to transform how PHEPR research is coordinated, sustainably funded, and conducted.

SOURCE: NOAA, 2020.

Methodological Challenges for PHEPR Research

The PHEPR field has generally relied on observational and quasi-experimental research designs, such as before–after studies, because more rigorous experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are often difficult and costly to develop and conduct given the unpredictability and dynamic context of public health emergencies. Because PHEPR often requires rapid decision making, such events typically allow little or no time to plan and prepare for evaluations or rapidly mobilize researchers. A number of practical issues that arise from the generally unpredictable nature of public health emergencies—such as those related to funding, ethical review, and data collection—add another layer of complexity to the conduct of research during such events. Outcomes that are more easily measurable, such as response times, are often not clearly linked to health outcomes or improved response or recovery (Nelson et al., 2007a). These challenges have impeded demonstrations of causal relationships among preparedness structures, response activities, and outcomes (Abramson et al., 2007; Asch et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 2007a).

Further differentiating PHEPR from other research fields is the inclusion of both traditional public health interventions (i.e., those aimed at improving population health outcomes) and those targeted toward improving systems and processes, such as improving the flow of information sharing, coordinating activities among response partners, or optimizing the acquisition and positioning of resources for a response. System changes often do not result in discrete outcomes but rather in adaptations within the system (Petticrew et al., 2019). While the overall aim of these system changes is to protect and improve the health of individuals and communities, their immediate effects may be shifts within the system, and it may be difficult if not impossible to attribute downstream outcomes, such as reduced mortality, to the changes with any certainty.

Past “evaluation” efforts in the PHEPR field have focused primarily on assessing the overall preparedness of the field and developing performance metrics, both of which are necessary, but differ from efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of specific PHEPR practices. For example, the National Health Security Preparedness Index was developed in an attempt to better understand the state of preparedness across SLTT agencies (RWJF, 2020). In a review of preparedness evaluation instruments, Asch and colleagues (2005) found that most of these instruments rely on subjective measures that have not been empirically validated (e.g., turnaround time for identification of pathogens in the laboratory; number of partner agencies that work together on a planning committee). Different benchmarks and performance measures have been developed and proposed over the years. For example, Khan and colleagues (2019) identified and defined a set of 67 PHEPR indicators, using a three-round modified Delphi technique, to advance performance measures for use by local and regional Canadian public health agencies in assessing readiness and measure improvement.

In the past, it has generally been held that the relative rarity of public health emergencies hinders the development of an evidence base for PHEPR. But it is becoming increasingly clear based on recent events—from hurricanes and wildfires to outbreaks of measles and the novel coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic—that this is no longer the case. The nation now is frequently facing public health emergencies that present opportunities to observe and learn and to conduct real-time research through which to develop a strong empirical and analytical evidence base for PHEPR practices. Furthermore, there is an ever-increasing array of research and evaluation approaches for complex interventions and systems, as well as opportunities to adapt methods from complementary scientific fields, such as anthropology and operations research. The wide range of existing research and evaluation designs (discussed further in Chapter 8) has yet to be fully brought to bear on the issues facing PHEPR practitioners.

A Poorly Organized Approach to PHEPR Research and Implications for the PHEPR Researcher Pipeline

As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 2, several transformational research programs and initiatives have advanced PHEPR as a field of study and contributed to the development of a PHEPR knowledge base. However, many of these programs are no longer funded and have been discontinued. Moreover, in the absence of a formal and clearly articulated research agenda, past research funding initiatives have largely been uncoordinated and limited by event, topic, and agency. As funding for PHEPR research has repeatedly stopped and restarted since the early 2000s, many of the interventional studies produced have been one-off (i.e., lacking the repetition needed to support strong conclusions about effectiveness), and the progression of an appropriately trained research workforce has stagnated (Keim et al., 2019). Consequently, the numbers of PHEPR researchers are insufficient to address the numerous knowledge gaps in the field.

A Well-Documented Gap Between PHEPR Research and Practice

The PHEPR field is driven by a culture of response, of which research is currently not an integral component. There is a notable cultural gap between responders, who are often focused on ending an emergency quickly and mitigating its effects, and researchers, who are driven to understand the science behind these events and the proposed courses of action (McNutt, 2015). In contrast with their counterparts in other fields, PHEPR researchers are often not practitioners, which contributes to the disconnect between practice and research. Moreover, administrative or quasi-legal boundaries often preclude researchers’ access to the response environment, limiting both their objective study of those environments (and hence the ability to produce useful research) and their ability to better understand the needs of practitioners through direct observation. Bridging the gap between research and practice is a daunting challenge, but PHEPR practitioners do not have decades to shift to evidence-based practices.

Furthermore, it is not clear that PHEPR practitioners have translated the evidence that does exist into their preparedness and response practices (Carbone and Thomas, 2018). Practitioners’ ability to successfully implement evidence-based practices is impeded by numerous barriers, such as lack of access to research, insufficient support and time, and resource constraints. One study found that information needs and awareness of existing research-based information differed between local and state public health departments, with the former expressing a greater need for information (Siegfried et al., 2017). Thus, barriers to translating research into practice may be greater for smaller, less well-resourced local health departments. Other barriers to translation of research into practice involve gaps between the studies that researchers conduct and the information needs of PHEPR practitioners, characteristics of a practice (e.g., high resource requirements or lack of adaptability), features of a particular setting, and failure of the research design to evaluate relevant implementation information (Glasgow and Emmons, 2007). Finally, decisions to implement evidence-based practices may be influenced by the perceived generalizability or applicability of research evidence to the diverse array of PHEPR practice contexts (e.g., emergency types, settings). PHEPR practices tend to be context sensitive, meaning that although a practice may have been shown to be effective in the specific context examined in a research study, the research findings do not necessarily translate to other practice settings.

THE IMPORTANCE OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE AND GUIDELINES

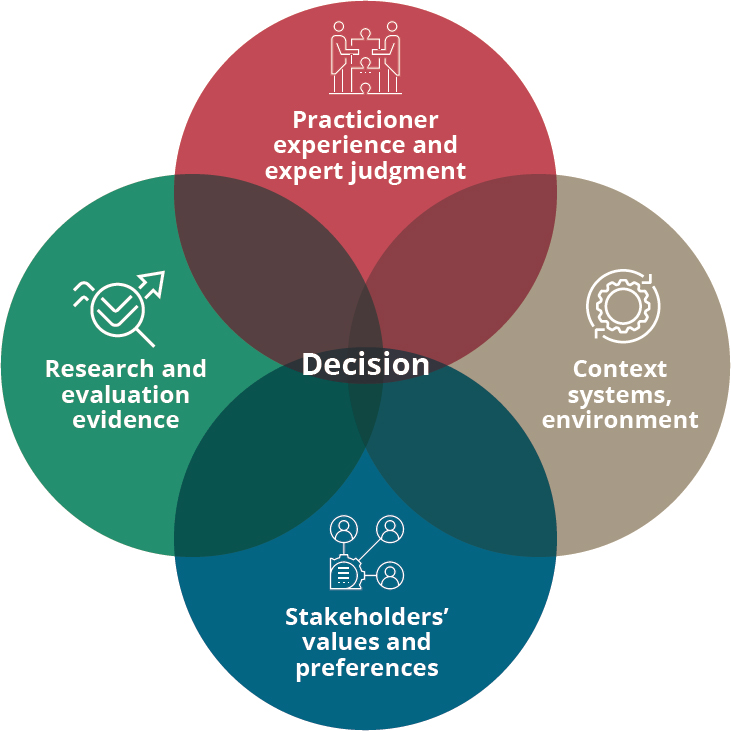

This report describes a process for synthesizing evidence on PHEPR practices to improve the accessibility of research and other evidence and its utility for evidence-informed decision making. Synthesizing the evidence from research is only one aspect of evidence-informed decision making. Evidence-informed decision making is the process of distilling and disseminating the best available evidence from research and evaluation; context, systems, and environment; stakeholders’ values and preferences; and practitioner experience and expert judgment and using that evidence to inform and improve practice and policy (Brownson et al., 2018) (see Figure 1-5). Figure 1-5 captures the various inputs to the evidence-informed decision-making process, and it is important to note that the nature of these inputs may be changing continuously during public health emergency response.

The direct and indirect benefits of identifying and using evidence-based practices are manifold, ranging from increasing the quality of information on which policies are based to greater workforce productivity, increased accountability, and more efficient use of resources (Brownson et al., 2009). In a recent Delphi study focused on improving the science and evidence base of disaster response, respondents agreed that the full range of review types should be used in a standardized way to synthesize evidence to inform contextually specific evidence of effectiveness in disaster response (Jillson et al., 2019).

SOURCE: Adapted from Barends et al., 2014.

The Emergence of Evidence-Based Guidelines and Policies to Promote Evidence-Based Practice

Outside of PHEPR, research in other fields has been translated into policy and practice through the establishment of task forces and clearinghouses that evaluate evidence and make recommendations for practice. For example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which uses evidence reviews to make recommendations on clinical preventive services, has been successful in identifying both effective and ineffective practices (e.g., screenings that are both unnecessary and potentially harmful) (Guirguis-Blake et al., 2007; HHS, 2010). Similarly, The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide) provides guidance on public health interventions and programs with the aim of promoting evidence-based practice in public health (Truman et al., 2000), using methods developed and implemented by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, convened by CDC. National and international organizations, such as Cochrane and the World Health Organization (WHO), regularly conduct robust evidence reviews that produce guidelines and recommendations (AHRQ, 2020; Cochrane, 2020; WHO, 2014). Evidence synthesis to support the uptake of evidence-based practices and policy also has spread beyond health care; other fields have adopted similar evidence review processes. Clearinghouses, such as the What Works Clearinghouse at the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institute of Justice’s CrimeSolutions program, evaluate evidence and make recommendations on evidence-based practices and policies (NIJ, 2013; WWC, 2017). Historically, however, many of these guideline groups have focused more on the effectiveness of specific interventions and less on the effectiveness of systems and policies or their implementation.

The move to evidence-based practice and policy in the United States is increasingly being driven by federal policy, including the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018.5 That act directed federal agencies to build evidence to support policy making and programs through the development of evidence plans (to include key research questions, data needs, and planned activities), the prioritization of evaluation activities, and the development of baseline information about the resources available for evidence building. More recently, Section 201(a) of the 2019 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act6 called for an evaluation of evidence-based benchmarks and objective standards in PHEPR.

Moving Beyond the Traditional Evidence Hierarchy for Evaluating the Effectiveness of PHEPR Practices

In the evaluation of interventions to improve health, the traditional hierarchy of evidence places systematic reviews of RCTs at the top (strongest evidence) and expert opinion at the bottom (weakest evidence). However, the traditional evidence hierarchy has limited applicability in such fields as PHEPR for a number of reasons. First, RCTs are likely to be unethical or infeasible for some PHEPR practices because of a lack of equipoise (genuine scientific uncertainty as to which randomization arm is best for participants) and the logistical challenges inherent in performing a randomized experiment in the context of an emergency (Durrheim and Reingold, 2010). Additionally, reductionist approaches like RCTs are not well suited to understanding the context-specific effects and interactions of systems and pro-

___________________

5 Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018. Public Law 115-435, 115th Cong. (January 14, 2019).

6 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2019. Public Law 109-417, 116th Cong. (June 24, 2019).

cesses (Rychetnik et al., 2002), which, as discussed earlier, are inherent in much of PHEPR. Thus, evidence from such research studies may have limited relevance with respect to its application in the field (Green and Glasgow, 2006). In contrast, well-controlled observational studies may be appropriate for answering many PHEPR research questions, especially those focused on how an intervention works rather than whether it works (Petticrew, 2003). Likewise, operational research and simulation studies may have more relevance than more experimental approaches to the everyday needs of PHEPR practitioners.

As noted previously, recent years have seen the development of new research disciplines, such as implementation science, and new methodologies for evidence synthesis that consider the complexity of systems and practices and make use of diverse sources of evidence, including that derived from qualitative and process evaluation research (Dixon-Woods et al., 2016; Harden et al., 2018; Lewin et al., 2018). These methods are being adopted by international guideline bodies, including WHO, and continue to be refined (Langlois et al., 2018; Swaminathan, 2019; Wieringa et al., 2018). This report builds on these developing methods to propose an evidence review and evaluation process that is suited to the PHEPR field (see Chapter 3).

ABOUT THIS REPORT

Study Approach and Scope

In developing this report and the recommendations presented herein, the committee deliberated for more than 2 years (from January 2018 through March 2020), holding 10 in-person meetings during that period. The meetings held in January 2018, April 2018, July 2018, and January 2019 included public information-gathering sessions that allowed the committee to hear from the study sponsor (CDC) and other experts and stakeholders (all public meeting agendas can be found in Appendix D). To supplement the stakeholder input received at these public meetings, a group of PHEPR practitioners were appointed as consultants to assist in refining the committee’s conceptual approach and to ensure that its recommendations would be grounded in practice.

As specified in the Statement of Task for this study (see Box 1-1), the committee was charged with selecting PHEPR practices to review from within the CDC PHEPR Capabilities (practices specific to the HPP were not within this study’s scope). Recognizing the considerable challenges inherent in this study, CDC did not constrain this review to a specific number of Capabilities and did not attempt to identify the Capabilities to be included in the review a priori. The Capabilities encompass a large number of PHEPR practices and potential evidence review questions. Given time and resource constraints, the committee recognized early on that it would be able to review only a very limited number of PHEPR practices and that this report would therefore represent a proof of concept rather than a comprehensive resource for PHEPR practitioners.

This report focuses primarily on SLTT public health agencies, while recognizing that these agencies do not exist in isolation and are part of a larger preparedness and response system that includes first responders, emergency management, and health care partners, among others. The committee understands that its findings may be applicable to other disciplines and, to increase the usefulness of this report to PHEPR stakeholders, considered the evidence in the context of all hazards.

The committee began by scoping the literature in the PHEPR field (see Chapter 2) to gain a sense of the nature of the evidence base and potential challenges related to evaluating the effectiveness of PHEPR practices. The committee then explored evaluation methodologies

that are used in health and other fields to synthesize and rate the strength of evidence. As discussed further in Chapter 3, there was no best-fit approach to evaluating PHEPR evidence, which does not fit easily into traditional, biomedical evidence review evaluations (Carbone and Thomas, 2018). Thus, the committee determined that a novel evidence evaluation methodology was necessary for PHEPR. The approach used to develop this proposed methodology is described in detail in Chapter 3.

Consistent with its charge, the committee applied its methodology to selected review topics to demonstrate how the methodology could accommodate different types of PHEPR practices and review questions. The committee used a careful topic selection process (described in Chapter 3 and in greater detail in Appendix A) to select four review topics, which represented diverse types of practices that require a flexible approach and different kinds of evidence to evaluate. The committee solicited literature on each of the selected PHEPR practices through a call for papers (discussed in more detail in Appendix A). The four practices the committee selected for review were

- engaging with and training community-based partners to improve the outcomes of at-risk populations after public health emergencies (falls under Capability 1, Community Preparedness);

- activating a public health emergency operations center (Capability 3, Emergency Operations Coordination [EOC]);

- communicating public health alerts and guidance with technical audiences during a public health emergency (Capability 6, Information Sharing); and

- implementing quarantine to reduce or stop the spread of a contagious disease (Capability 11, Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions).

The core set of terms used throughout the report are those used routinely by policy makers, practitioners, researchers, and the public. Yet, while these terms are commonly used, their definitions are nuanced and can vary depending on the particular context and user. Box 1-4 presents the committee’s definitions for these core terms. In addition to these terms, other important terms are defined throughout the report alongside the relevant discussion.

Report Audiences and Uses

In developing its evidence review methodology, the committee understood the nature of decision making required in responding to a public health emergency and the need for clear, accessible, and adaptable guidance on evidence-based practices. Throughout this report, the committee seeks to guide practitioners, policy makers, and other stakeholders in understanding and using the available evidence to inform their decision making. Accordingly, this report is intended to inform a wide range of audiences and has different potential uses for each, including the following:

- Policy makers can use the report to build a sustainable process with the necessary oversight and support for ongoing evaluation of the PHEPR literature to identify evidence-based practices and critical knowledge gaps that need to be addressed through future research initiatives. They can also identify other strategies for strengthening the PHEPR evidence base, for example, by incentivizing the routine evaluation of practices through quality improvement approaches, supporting the continued development of PHEPR as a unique academic discipline, and better integrating PHEPR practice and research.

| BOX 1-4 | CORE TERMS USED THROUGHOUT THE REPORT |

Evidence-based interventions: “Public health practices and policies that have been shown to be effective based on evaluation research. Often, lists of evidence-based interventions are identified through systematic reviews, but they sometimes need adaptation to unique or varied settings, populations, or circumstances” (Brownson et al., 2018, p. 3.2).

Evidence-informed decision making: “The process of distilling and disseminating the best available evidence from research, context, and experience (political, organizational) and using that evidence to inform and improve public health practice and policy” (Brownson et al., 2018, p. 3.2).

Mixed-method evidence synthesis: An evidence synthesis approach involving the integration of quantitative, mixed-method, and qualitative evidence in a single review (Petticrew et al., 2013).

Public health emergency: For the purposes of this report, defined as a situation with health consequences whose scale, timing, or unpredictability threatens to overwhelm routine capabilities (Nelson et al., 2007b).

Public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR): “The capability of the public health and health care systems, communities, and individuals to prevent, protect against, quickly respond to, and recover from health emergencies, particularly those whose scale, timing, or unpredictability threatens to overwhelm routine capabilities” (Nelson et al., 2007b, p. S-9).

Public health emergency preparedness and response practice: A type of process, structure, or intervention whose implementation is intended to mitigate the adverse effects of a public health emergency on the population as a whole or a particular sub-group within the population.

Public health systems research: “A field of study that examines the organization, financing, and delivery of public health services within communities and the impact of these services on public health” (Mays et al., 2003, p. 180).

- PHEPR researchers can find information regarding key elements of research design and reporting that would strengthen the quality of evidence supporting PHEPR practices and improve the usefulness of their research. They can also find detailed information about critical gaps in the PHEPR evidence base that are priority areas for further exploration.

- Methodologists and other researchers interested in the field of evidence synthesis and guideline development can gain a deeper understanding of mixed-method approaches to evidence synthesis and the challenges associated with evaluation of complex interventions.

- SLTT public health agencies, and specifically PHEPR practitioners, can learn of strategies for engaging in the evidence review process and for implementing evidence-based practices in their own organizations, as well as ways to improve the capture of evidence from real-world practice experience. And as previously emphasized, in addition to public health agencies, this information should be useful to those who have roles in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from public health emergencies, such as first responders, health care stakeholders, and emergency management professionals.

- Organizations that fund PHEPR research (i.e., federal or other national agencies and nongovernmental organizations and foundations) can find information to help organize and guide their decisions about investments in PHEPR research and evaluation, as well as strategies that can be used to incentivize improvements in the quality of research.

- Professional associations that represent the PHEPR community, public health accreditation bodies, and journals can learn of ways to support and promote the generation, dissemination, and adoption of evidence-based PHEPR practices.

In sum, the report collectively defines a framework for a system that together practitioners, researchers, and policy makers can implement to address current gaps in PHEPR practitioners’ access to information on evidence-based PHEPR practices.

Organization of the Report

This report is organized around the following two distinct aspects of the committee’s Statement of Task (see Box 1-1), each of which comes with its own set of recommendations:

- developing the methodology for and subsequently conducting a systematic review and evaluation of the evidence for PHEPR practices and making recommendations on adoption of PHEPR practices based on evidence of effectiveness (bullets 1–4 in the Statement of Task); and

- providing recommendations for future research needed to address critical gaps in evidence-based PHEPR practices, as well as processes needed to improve the overall quality of evidence within the field (bullet 5 in the Statement of Task).

Review Methodology, Evidence Reviews, and Recommendations for Evidence-Based PHEPR Practices

Chapter 3 describes the committee’s proposed methodology for reviewing and evaluating the evidence for PHEPR practices. So as to focus the chapter on the original aspects of the committee’s methodology, details related to processes that are fairly standard in systematic reviews (i.e., the selection of review topics, the literature searches, and the data extraction and quality assessment of individual articles) are included in Appendix A. An evidence-based practice center (EPC) was commissioned to conduct the data extraction and quality assessment of individual quantitative studies. Appendix C contains a link to the EPC’s report, which describes the EPC’s methods and includes tables containing the extracted data and quality assessments.

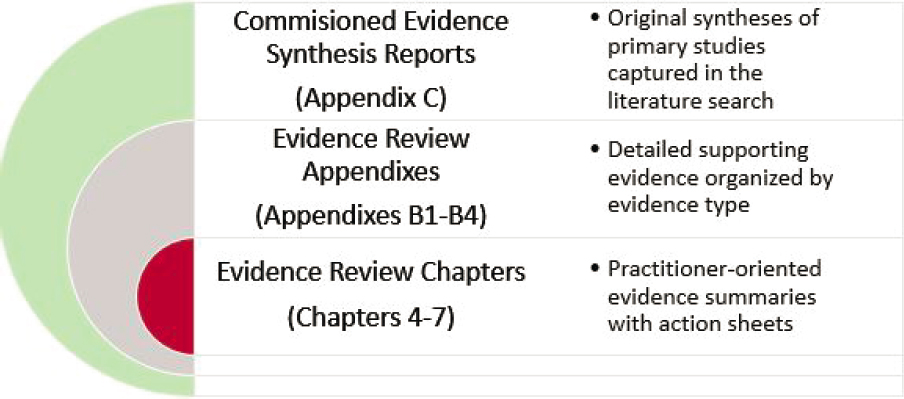

As it was expected that different report audiences would be interested in different levels of detail on various topics, the committee took a layered approach to presenting the findings of its four evidence reviews (see Figure 1-6). Chapters 4–7 are oriented toward PHEPR practitioners and, respectively, present high-level summaries of the evidence for the four PHEPR practices selected for review (as detailed earlier) in a user-friendly format. Each of these chapters provides the following:

- a two-page action sheet at the front of the chapter that presents PHEPR practitioners and other users with the key takeaways from the review;

- background information on the practice, including a definition, an analytic framework with the hypothesized links between the practice and the outcomes of interest, and a description of the scope of the problem addressed by the practice;

- an overview of the evidence base, including evidence of effectiveness, benefits and harms, acceptability and preferences, feasibility and PHEPR system considerations, resources and economic considerations, equity, and ethical considerations;

- the practice recommendation (when supported by sufficient evidence), along with a justification and specific implementation guidance; and

- priorities for future research to improve the evidence base for the practice.

For those audiences seeking additional, more detailed information, each review chapter has an associated appendix (see Appendixes B1–B4) containing a comprehensive description of the evidence base for the respective PHEPR practice. To facilitate the linkage between the evidence summaries in Chapters 4–7 and the body of studies from which the findings were generated, summaries in the evidence review chapters reference specific numbered sections in the appendixes.

Of note, external experts were commissioned to carry out some components of the committee’s evidence reviews: the syntheses of the bodies of qualitative evidence, the syntheses of the experiential-based evidence from case reports and after action reports, and the synthesis of a selection of modeling studies for one of the evidence reviews. The main findings from these commissioned reports were incorporated in the detailed evidence reviews presented in Appendixes B1–B4, but for those audiences who would like to review the commissioned authors’ descriptions and findings, Appendix C includes links to each of the commissioned reports.

Processes Needed to Improve the Overall Quality of Evidence Within the Field

The remaining two chapters of the report focus on the second main aspect of the committee’s task—identifying and recommending processes needed to improve the overall quality of evidence within the field. Chapter 2 begins with a high-level overview of the state of PHEPR research based on the results of a commissioned scoping review for the 15 PHEPR Capabilities and associated evidence maps identifying key gaps and limitations in

the PHEPR evidence base (Appendix D contains an excerpt from the commissioned authors’ report and the evidence maps). The chapter then examines the evolution of the PHEPR research enterprise and the underlying reasons for the current state of the evidence. Finally, Chapter 8 presents the committee’s overarching recommendations for improving the quality of PHEPR research, including the role that funders, researchers, and practitioners can play in advancing the evidence base.

Other Appendixes

Appendix E provides the agendas for the committee’s public meetings and links to the committee’s Workshop Proceedings—in Brief, which summarizes a public workshop on evidence evaluation methodologies and is available online through the National Academies Press. Appendix F presents biographical sketches of the committee members.

REFERENCES

Abramson, D. M., S. S. Morse, A. L. Garrett, and I. Redlener. 2007. Public health disaster research: Surveying the field, defining its future. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1(1):57–62.

Acosta, J. D., C. Nelson, E. B. Beckjord, S. R. Shelton, E. Murphy, K. L. Leuschner, and J. Wasserman. 2009. A national agenda for public health systems research on emergency preparedness. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2020. Research findings. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/index.html (accessed February 19, 2020).

Asch, S. M., M. Stoto, M. Mendes, R. B. Valdez, M. E. Gallagher, P. Halverson, and N. Lurie. 2005. A review of instruments assessing public health preparedness. Public Health Reports 120(5):532–542.

ASPR (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response). 2016. 2017–2022 health care preparedness and response capabilities. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/reports/Documents/20172022-healthcare-pr-capablities.pdf (accessed May 14, 2020).

ASPR. 2019. Hospital preparedness program. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/Pages/default.aspx (accessed March 27, 2020).

Barends, E., D. M. Rousseau, and R. B. Briner. 2014. Evidence-based management: The basic principles. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Center for Evidence-Based Management. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Evidence-Based-Practice-The-Basic-Principles.pdf (accessed March 2, 2020).

Brownson, R. C., J. E. Fielding, and C. M. Maylahn. 2009. Evidence-based public health: A fundamental concept for public health practice. Annual Review of Public Health 30:175–201.

Brownson, R. C., J. E. Fielding, and L. W. Green. 2018. Building capacity for evidence-based public health: Reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annual Review of Public Health 39(1).

Bunnell, R. E., Z. Ahmed, M. Ramsden, K. Rapposelli, M. Walter-Garcia, E. Sharmin, and N. Knight. 2019. Global health security: Protecting the United States in an interconnected world. Public Health Reports 134(1):3–10.

Carbone, E. G., and E. V. Thomas. 2018. Science as the basis of public health emergency preparedness and response practice: The slow but crucial evolution. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S383–S386.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2018. Public health emergency preparedness and response capabilities: National standards for state, local, tribal, and territorial public health. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/capabilities.htm (accessed February 19, 2020).

CDC. 2019a. Cities readiness initiative. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/mcm/cri.html (accessed February 19, 2020).

CDC. 2019b. Public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement: CDC-RFA-TP19-1901. https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/view-opportunity.html?oppId=310318 (accessed May 14, 2020).

CDC. 2020. Public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/phep.htm (accessed March 3, 2020).

Cochrane. 2020. About us. https://www.cochrane.org/about-us (accessed February 19, 2020).

Dixon-Woods, M., S. Bonas, A. Booth, D. R. Jones, T. Miller, A. J. Sutton, R. L. Shaw, J. A. Smith, and B. Young. 2016. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research 6(1):27–44.

Durrheim, D. N., and A. Reingold. 2010. Modifying the grade framework could benefit public health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 64(5):387.

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2020. Homeland security grant program. https://www.fema.gov/homeland-security-grant-program (accessed February 19, 2020).

Gibson, P. J., F. Theadore, and J. B. Jellison. 2012. The common ground preparedness framework: A comprehensive description of public health emergency preparedness. American Journal of Public Health 102(4):633–642.

Glasgow, R. E., and K. M. Emmons. 2007. How can we increase translation of research into practice? Types of evidence needed. Annual Review of Public Health 28(1):413–433.

Green, L. W., and R. E. Glasgow. 2006. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: Issues in external validation and translation methodology. Evaluation and the Health Professions 29(1):126–153.

Guirguis-Blake, J., N. Calonge, T. Miller, A. Siu, S. Teutsch, E. Whitlock, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2007. Current processes of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Refining evidence-based recommendation development. Annals of Internal Medicine 147(2):117–122.

Harden, A., J. Thomas, M. Cargo, J. Harris, T. Pantoja, K. Flemming, A. Booth, R. Garside, K. Hannes, and J. Noyes. 2018. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series-paper 5: Methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 97:70–78.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Evidence-based clinical and public health: Generating and applying the evidence: Secretary’s advisory committee on national health promotion and disease prevention objectives for 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/EvidenceBasedClinicalPH2010.pdf (accessed March 2, 2020).

HHS. 2019a. National health security strategy 2019–2022. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/authority/nhss/Documents/NHSS-Strategy-508.pdf (accessed March 2, 2020).

HHS. 2019b. Strategic national stockpile. https://www.phe.gov/about/sns/Pages/default.aspx (accessed February 19, 2020).

HHS. 2020. Biomedical advanced research and development authority. https://www.phe.gov/about/barda/Pages/default.aspx (accessed February 19, 2020).

Horney, J. 2019 (unpublished). The public health emergency preparedness and response system: A comprehensive review. Paper commissioned by the Committee on Evidence-Based Practices for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response.

Horney, J., E. G. Carbone, M. Lynch, C. J. Shuang, and T. Jones. 2019. How public health agencies use the public health emergency preparedness capabilities. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2019.133.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2008. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems: A letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jillson, I. A., M. Clarke, C. Allen, S. Waller, T. Koehlmoos, W. Mumford, J. Jansen, K. McKay, and A. Trant. 2019. Improving the science and evidence base of disaster response: A policy research study. BMC Health Services Research 19(1):274.

Keim, M., T. D. Kirsch, and A. Lovallo. 2019. A comparison of us federal government spending for research and development related to public health preparedness capabilities, 2008–2017. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1–8.

Khan, Y., G. Fazli, B. Henry, E. de Villa, C. Tsamis, M. Grant, and B. Schwartz. 2015. The evidence base of primary research in public health emergency preparedness: A scoping review and stakeholder consultation. BMC Public Health 15(432).

Khan, Y., T. O’Sullivan, A. Brown, S. Tracey, J. Gibson, M. Généreux, B. Henry, and B. Schwartz. 2018. Public health emergency preparedness: A framework to promote resilience. BMC Public Health 18(1344).

Khan, Y., A. D. Brown, A. R. Gagliardi, T. O’Sullivan, S. Lacarte, B. Henry, and B. Schwartz. 2019. Are we prepared? The development of performance indicators for public health emergency preparedness using a modified Delphi approach. PLOS ONE 14(12).

Langlois, E. V., K. Daniels, and E. A. Akl. 2018. Evidence synthesis for health policy and systems: A methods guide. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/publications/Alliance-evidencesynthesis-MethodsGuide.pdf?ua=1 (accessed March 3, 2020).

Lewin, S., A. Booth, C. Glenton, H. Munthe-Kaas, A. Rashidian, M. Wainwright, M. A. Bohren, Ö. Tunçalp, C. J. Colvin, R. Garside, B. Carlsen, E. V. Langlois, and J. Noyes. 2018. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implementation Science 13(1):2.

Linkov, I., T. Bridges, F. Creutzig, J. Decker, C. Fox-Lent, W. Kroger, J. H. Lambert, A. Levermann, B. Montreuil, J. Nathwani, R. Nyer, O. Renn, B. Scharte, A. Scheffler, M. Schreurs, and T. Thiel-Clemen. 2014. Changing the resilience paradigm. Nature Climate Change 4:407–409.

Maddock, J. E., S. A. Payne, S. Jett, and M. Kellman. 2018. Translation, dissemination, and implementation of public health preparedness research and training: Introduction and contents of the volume. 108(S5):S349–S350.

Martinez, D., T. Talbert, S. Romero-Steiner, C. Kosmos, and S. Redd. 2019. Evolution of the public health preparedness and response capability standards to support public health emergency management practices and processes. Health Security 17(6):430–438.

Mays, G. P., P. Halverson, and F. D. Scutchfield. 2003. Behind the curve? What we know and need to learn from public health systems research. Journal of Public Health Management Practice 9(3):179–182.

McNutt, M. 2015. A community for disaster science. Science 348(6230):11.

Nelson, C., N. Lurie, and J. Wasserman. 2007a. Assessing public health emergency preparedness: Concepts, tools, and challenges. Annual Review of Public Health 28(1):1–18.

Nelson, C., N. Lurie, J. Wasserman, and S. Zakowski. 2007b. Conceptualizing and defining public health emergency preparedness. American Journal of Public Health 97(S1):S9–S11.

Nelson, C. D., E. B. Beckjord, D. J. Dausey, E. Chan, D. Lotstein, and N. Lurie. 2008. How can we strengthen the evidence base in public health preparedness? Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2(4):247–250.

NIJ (National Institute of Justice). 2013. Crimesolutions.gov practices scoring instrument. https://www.crimesolutions.gov/pdfs/PracticeScoringInstrument.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2020. Billion-dollar weather and climate disasters: Overview. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions (accessed Febuary 12, 2020).

Petticrew, M. 2003. Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: Horses for courses. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 57(7):527–529.

Petticrew, M., E. Rehfuess, J. Noyes, J. P. T. Higgins, A. Mayhew, T. Pantoja, I. Shemilt, and A. Sowden. 2013. Synthesizing evidence on complex interventions: How meta-analytical, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches can contribute. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 66(11):1230–1243.

Petticrew, M., C. Knai, J. Thomas, E. A. Rehfuess, J. Noyes, A. Gerhardus, J. M. Grimshaw, H. Rutter, and E. McGill. 2019. Implications of a complexity perspective for systematic reviews and guideline development in health decision making. BMJ Global Health 4:e000899. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000899.

Qari, S. H., M. R. Leinhos, T. N. Thomas, and E. G. Carbone. 2018. Overview of the translation, dissemination, and implementation of public health preparedness and response research and training initiative. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S355–S362.

Rose, D. A., S. Murthy, J. Brooks, and J. Bryant. 2017. The evolution of public health emergency management as a field of practice. American Journal of Public Health 107(S2):S126–S133.

RWJF (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). 2020. National health security preparedness index. https://nhspi.org (accessed May 20, 2020).

Rychetnik, L., M. Frommer, P. Hawe, and A. Shiell. 2002. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56(2):119–127.

Savoia, E., S. Guicciardi, D. P. Bernard, N. Harriman, M. Leinhos, and M. Testa. 2018. Preparedness emergency response research centers (PERRCs): Addressing public health preparedness knowledge gaps using a public health systems perspective. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S363–S365.

Siegfried, A. L., E. G. Carbone, M. B. Meit, M. J. Kennedy, H. Yusuf, and E. B. Kahn. 2017. Identifying and prioritizing information needs and research priorities of public health emergency preparedness and response practitioners. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 11(5):552–561.

Stoto, M. A., C. Nelson, E. Savoia, I. Ljungqvist, and M. Ciotti. 2017. A public health preparedness logic model: Assessing preparedness for cross-border threats in the European region. Health Security 15(5):473–482.

Swaminathan, S. 2019. How to shape research to advance global health. Nature 569(7754):7.

Truman, B. I., C. K. Smith-Akin, A. R. Hinman, K. M. Gebbie, R. C. Brownson, L. F. Novick, R. Lawrence, M. Pappaioanou, J. E. Fielding, C. Evans, F. A. Guerra, M. Vogel-Taylor, C. Mahan, M. Fullilove, S. Zaza, and The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2000. Developing the guide to community preventive services: Overview and rationale. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 18:18–26.

VanDevanter, N., P. Leviss, D. Abramson, J. M. Howard, and P. A. Honoré. 2010. Emergency response and public health in Hurricane Katrina: What does it mean to be a public health emergency responder? Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 16(6):E16–E25.

Watson, C. R., M. Watson, and T. K. Sell. 2017. Public health preparedness funding: Key programs and trends from 2001 to 2017. American Journal of Public Health 107(S2):S165–S167.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2009. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44204/9789241563895_eng.pdf;jsessionid=F75F0B4C38F0CA8AD59F8B7446D8B916?sequence=1 (accessed March 3, 2020).

WHO. 2014. WHO handbook for guideline development, 2nd ed. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714 (accessed February 19, 2020).

Wieringa, S., D. Dreesens, F. Forland, C. Hulshof, S. Lukersmith, F. Macbeth, B. Shaw, A. van Vliet, T. Zuiderent-Jerak, and AID Knowledge Working Group of the Guidelines International Network. 2018. Different knowledge, different styles of reasoning: A challenge for guideline development. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 23(3):87–91.

WWC (What Works Clearinghouse). 2017. What Works Clearinghouse standards handbook, version 4.0. Washington, DC: Institute of Education Sciences.