2

The Landscape and Evolution of Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Research in the United States

The complexities of the public health emergency preparedness and response (PHEPR) system and the unique challenges of conducting research on PHEPR practices,1 as discussed in Chapter 1, have impeded efforts to build a cumulative evidence base for the field. This chapter examines how these challenges have been compounded by funding issues and unclear prioritization of research topics. The chapter begins with a description of the state of the evidence in the PHEPR research field, informed by a scoping review and series of evidence maps commissioned by the committee. This discussion is followed by an examination of the evolution of the PHEPR research field. The chapter concludes with an explanation of how the current approach to coordinating, funding, and conducting PHEPR research is inadequate for improving the quality of evidence in the field.

CHARACTERIZING THE RESEARCH ON PHEPR: A MAP OF THE EVIDENCE

An increasing number of PHEPR research studies have been produced over the past two decades, but these studies are often dispersed across topics and sources, and as a result, it is not clear which specific areas need further research. Several scoping reviews of the PHEPR research literature have identified important knowledge gaps and research priorities (Abramson et al., 2007; Acosta et al., 2009; Birnbaum et al., 2017; Challen et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2015; Savoia et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018; Yeager et al., 2010). In general, these scoping reviews have found that the PHEPR evidence base was increasing with respect to the number of articles published but was overwhelmingly descriptive, lacking in objective evaluations and quantitative analyses and unbalanced in focus across the emergency cycle, with a majority of articles being focused on the preparedness and response phases.

___________________

1 The committee defined PHEPR practices broadly as a type of process, structure, or intervention whose implementation is intended to mitigate the adverse effects of a public health emergency on the population as a whole or a particular sub-group within the population.

PHEPR research tends to be reactive and opportunistic—following a disaster, numerous event-specific research articles appear in the literature—and not always coordinated, timely, or focused on answering the most important questions (Elsevier, 2017). This situation does, however, appear to be changing. A review conducted by Savoia and colleagues (2017) found that PHEPR research has evolved over the past two decades, from generic inquiry to a more critical analysis of specific interventions and with an increase in empirical studies.

While all of these scoping reviews have added value in identifying common themes across the evidence base and noting particular knowledge gaps, none of them has focused purposefully on the 15 PHEPR Capabilities, which are fundamental in guiding state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies in assessing, building, and sustaining PHEPR capacity. To address this gap, the committee sought to understand the extent, range, and nature of PHEPR research across the 15 PHEPR Capabilities, with a specific focus on studies that evaluate the impact of PHEPR practices, and commissioned an expert group to visualize these findings using high-level evidence maps (see Appendix D). Evidence maps are a relatively new form of evidence synthesis whose purpose is to identify research gaps and future research needs (Miake-Lye et al., 2016). An understanding of where evidence exists and where little to no evidence exists across the 15 PHEPR Capabilities can help stakeholders interpret the state of the evidence and inform policy decision making and priorities for future research.

Overall Distribution of Articles Within the 15 PHEPR Capabilities

A total of 1,692 articles (published 2001–2019)—consisting of quantitative (comparative and noncomparative) impact, quantitative nonimpact, qualitative, and modeling studies; literature reviews; after action reports (AARs) and case reports; and commentaries—were initially included in the commissioned scoping review.2 Ultimately, the committee was most interested in those studies that could potentially provide evidence regarding the 15 PHEPR Capabilities. Therefore, after this initial classification of all study designs, commentaries and literature reviews were excluded from subsequent analyses, resulting in a total of 1,106 articles for final inclusion.

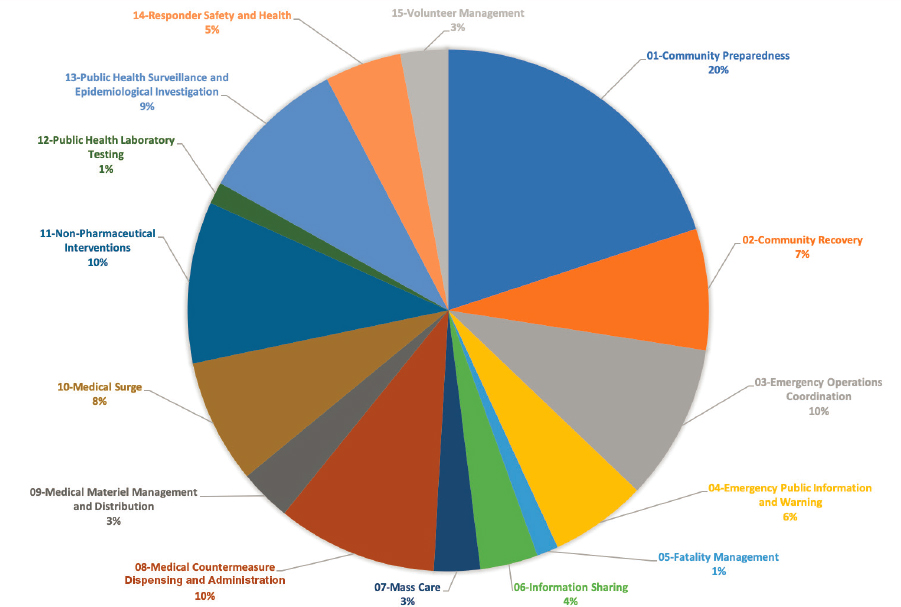

Figure 2-1 displays the distribution of articles across the 15 PHEPR Capabilities. The highest percentage of articles mapped to the Community Preparedness Capability (20 percent of the 1,106 articles), followed by the Emergency Operations Coordination, Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration, and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions Capabilities, each at 10 percent. It is not surprising that the greatest proportion of research addresses the Community Preparedness Capability because it is the broadest of the Capabilities, covering topics from at-risk populations and community partnership building to strengthening of personal preparedness and training and education (CDC, 2018). Furthermore, research on the Capabilities is conducted primarily in nonemergency times. The Capabilities with the lowest percentage of articles include Fatality Management and Public Health Laboratory

___________________

2 The scoping review’s methodology, including search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and limitations, is described in the commissioned paper documenting the review titled “Review and Evidence Mapping of Scholarly Publications Within CDC’s 15 Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities,” by Testa and colleagues (see Appendix D). The task of finding and classifying the body of research underlying all of the 15 PHEPR Capabilities was challenging because of the broad scope, complexity, and nature of the research topics. The evidence maps that resulted from the review certainly do not contain every published study examining PHEPR practices since 2001. The scoping review did not attempt to capture after action reports not published in journals and searchable in bibliographic databases. Future efforts could focus on conducting detailed scoping reviews on specific Capabilities or practices.

Testing, both at 1 percent. Notably, for both of these Capabilities, most of the supporting research would be expected to have occurred outside of the PHEPR field, which may help explain the low numbers of studies. Public Health Laboratory Testing is foundational public health practice, and for Fatality Management, public health agencies often play supporting roles and coordinate with partner organizations and agencies to provide services.

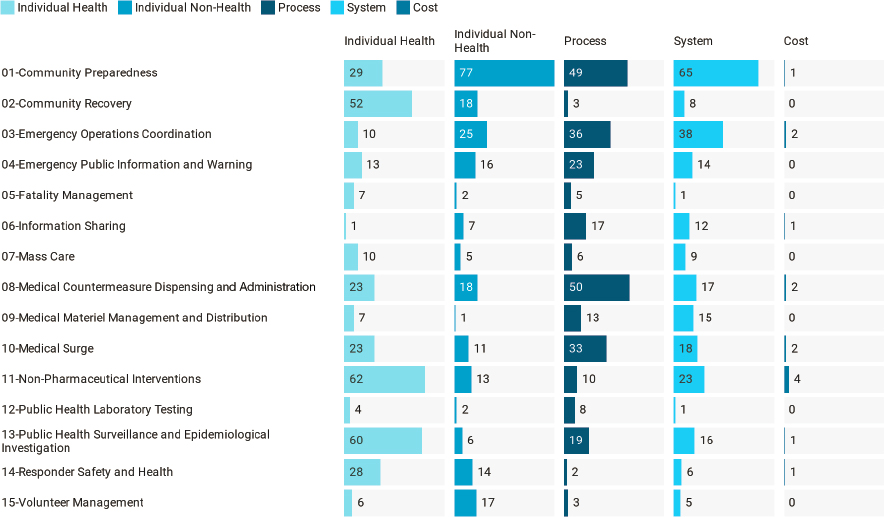

Figure 2-2 shows that overall, the numbers of studies are relatively evenly split across types of outcomes, with the exception of cost outcomes (1 percent of all studies). Individual health outcomes3 are examined in 30 percent of the studies. Capabilities with individual health outcomes as their most common outcome type include Community Recovery, Fatality Management, Mass Care, Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, Public Health Surveillance and Epidemiological Investigation, and Responder Safety and Health. These Capabilities are fundamentally different from those with process outcomes, namely Emergency Public Information and Warning, Information Sharing, Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration, Medical Surge, and Public Health Laboratory Testing. The former set of Capabilities focuses on practices that more directly impact human health and well-being, while the latter set focuses on processes of the PHEPR system (e.g., information dissemination, dispensing, and testing). Individual nonhealth outcomes align most strongly with the Community Preparedness and Volunteer Management Capabilities, which likely reflects the emphasis on planning and training for those two Capabilities. Research that maps to the Emergency Operations Coordination and Medical Materiel Management and Distribution Capabilities most often assesses system-level outcomes.

___________________

3 Individual health outcomes include morbidity-, mortality-, clinical/surgical-, and psychological-related outcomes.

Quantitative Impact Studies Within the 15 PHEPR Capabilities

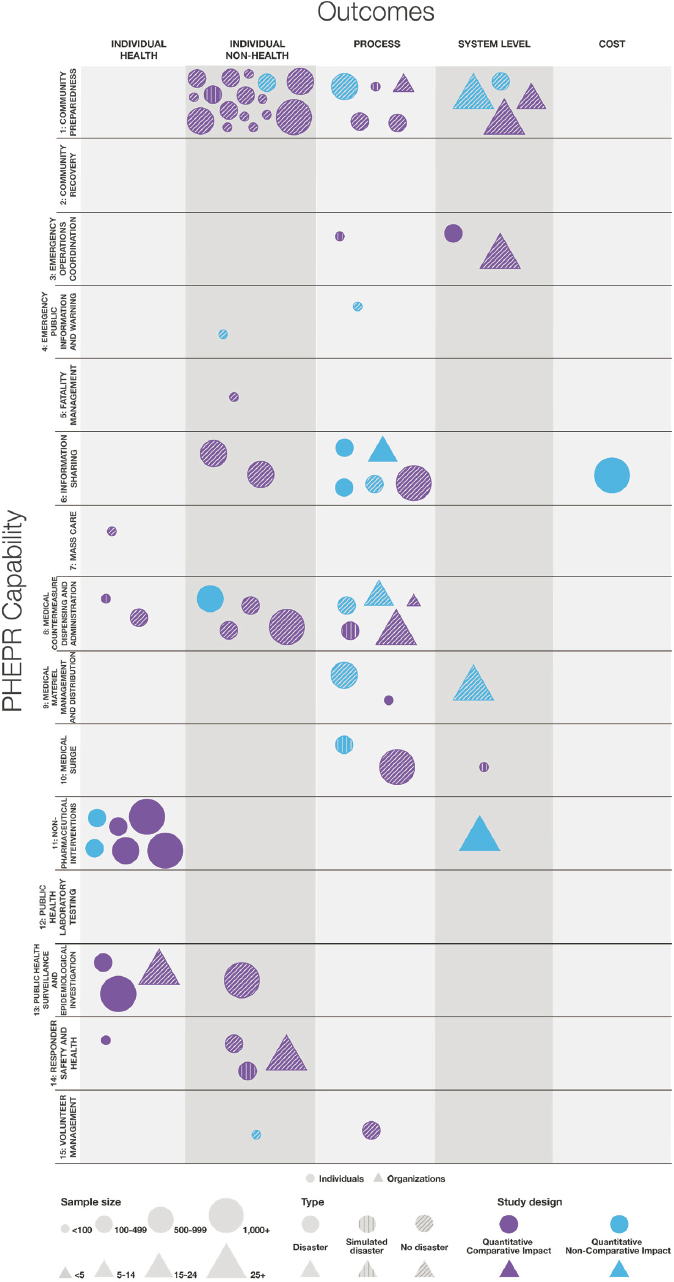

Among the 1,106 evidentiary studies, only 95 (8.5 percent) are categorized as quantitative impact studies—meaning they evaluated specific PHEPR practices.4 Of these 95 studies, 22 are noncomparative and 73 comparative. The majority (72 of 95) are based in the United States. Figure 2-3 illustrates the 72 quantitative impact studies conducted in the United States by outcome (an evidence map for the non-U.S. quantitative impact studies can be found in Appendix D).

It is important to note that the distribution of U.S. quantitative impact studies across the 15 PHEPR Capabilities largely reflects the overall distribution of studies, with the exception of the Emergency Operations Coordination Capability (see Figure 2-1). Emergency Operations Coordination is examined in 10 percent of all studies, equal to the proportions for Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, but has only 3 quantitative impact studies, while the other Capabilities have 11 and 7, respectively. Given that Emergency Operations Coordination comprises largely organizational, behavioral, and management practices, which are likely to be highly context-specific, this Capability, in contrast to Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions, may be better suited to quality improvement

___________________

4 Three types of evidence are defined in evidence-based public health: Type 1 is research that describes risk–disease relations and identifies the magnitude, severity, and preventability of public health problems; Type 2 is research that identifies the relative effectiveness of specific interventions aimed at addressing a problem; and Type 3 is research on the design and implementation of an intervention, the contextual circumstances in which the intervention was implemented, and how the intervention was received. Quantitative nonimpact studies encompass Type 1 evidence, and quantitative impact studies encompass Types 2 and 3 (Rychetnik et al., 2004). All three evidence types result from “evidentiary studies,” which are characterized by some form of systematic data collection and analysis that could provide evidence regarding the PHEPR Capabilities. Nonevidentiary studies include opinion pieces, concept papers, and commentaries, as well as literature reviews.

evaluations relative to research studies aimed at generating generalizable knowledge. This notion is supported by the observation that the three Emergency Operations Coordination quantitative impact studies examine response trainings and processes.

It is unsurprising that there are only one to two quantitative impact studies each for the Capabilities of Fatality Management, Mass Care, and Volunteer Management, and none examining Public Health Laboratory Testing, as only 1 to 3 percent of all included studies fall within these Capabilities. Consistent with the overall distribution of U.S. studies, a majority of the quantitative impact studies map to Community Preparedness, and many of these comparative impact studies are pre-post test studies of trainings and educational programs. No quantitative impact studies examining Community Recovery were identified. A majority of Community Recovery studies are quantitative nonimpact designs, which is not surprising given that a large share of the focus and efforts after public health emergencies consists of assessing, monitoring, and surveilling health, disease, and injury among the impacted community to identify adverse health effects. However, this preponderance of nonimpact designs does demonstrate the significant gap in studies evaluating the impact of PHEPR programs and practices. The paucity of studies for Emergency Public Information and Warning (just two) probably reflects the fact that practices would be expected to be grounded in the risk communication literature more broadly; thus, it is likely that some impact research has occurred outside of the PHEPR field and was not captured in this scoping review.

Given the dearth of research examining cost-related outcomes across all 1,160 studies, it is not surprising that there is only one quantitative impact study (for the Information Sharing Capability) examining cost. Process and systems-level outcomes, combined, are the most predominant outcomes examined in all 1,106 studies; however, it appears that individual-level health (e.g., morbidity and mortality) and nonhealth (e.g., knowledge and behavior) outcomes are more predominant among the quantitative impact studies. As noted, the vast majority of studies examining most of the 15 PHEPR Capabilities were not conducted during a real disaster, the exception being those examining Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions.

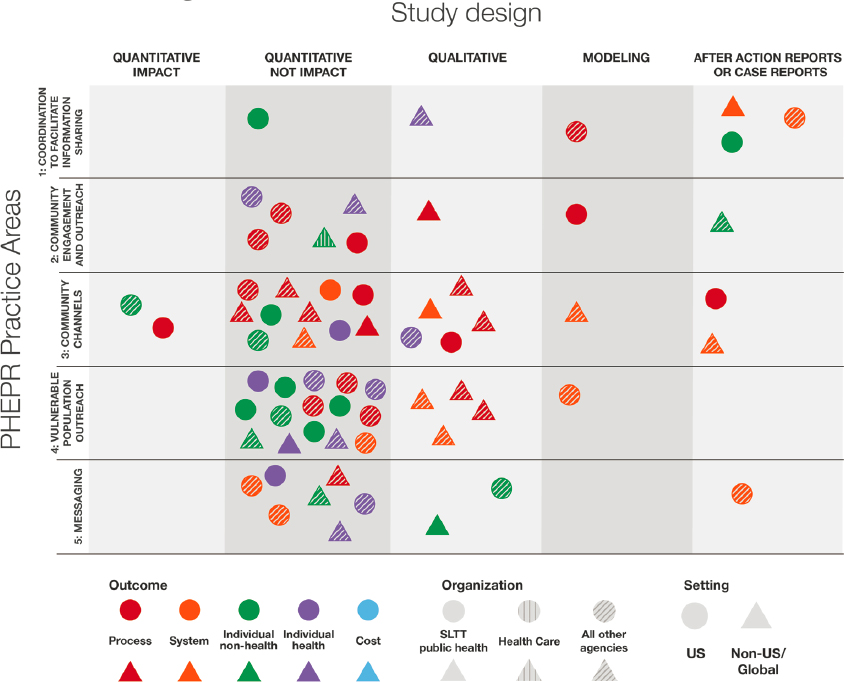

Studies Within Specific Practice Areas of the 15 PHEPR Capabilities

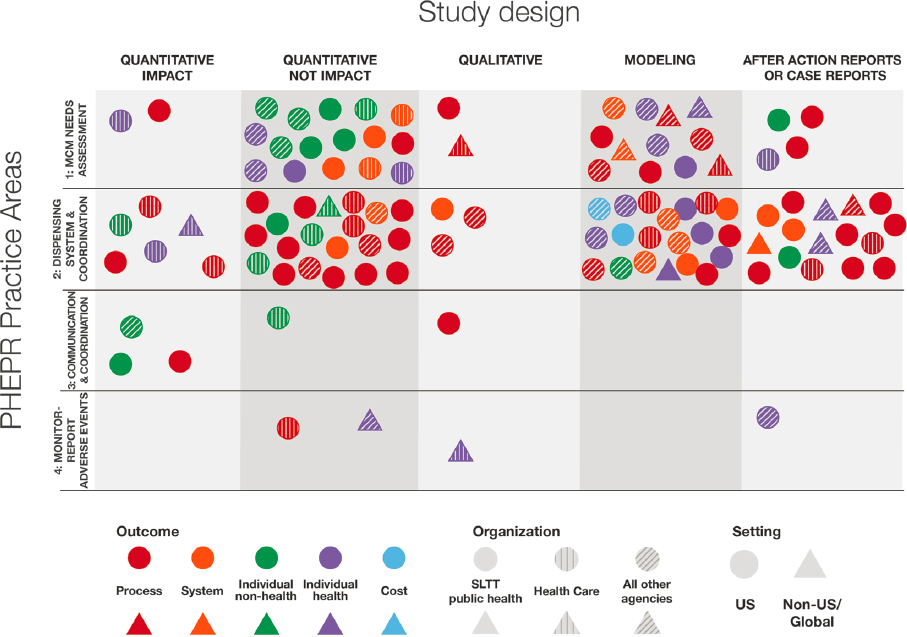

The committee was interested in examining the distribution of studies not only across the 15 PHEPR Capabilities but also across specific PHEPR practice areas within individual Capabilities.5 Evidence maps for each of the 15 PHEPR Capabilities can be found in Appendix D; one is discussed here as an illustrative example. As a whole, however, the maps in Appendix D show that the distribution of quantitative impact studies is uneven, with few (and in some cases no) such studies for the majority of PHEPR practices.

Figure 2-4 shows the characteristics of the 110 studies addressing PHEPR practice areas within the Medical Countermeasure Dispensing and Administration Capability. Notably, there are gaps in the practice areas of communication and coordination for effective dispensing and monitoring of adverse events. The monitoring of adverse events following dispensing of medical countermeasures has previously been highlighted as a gap in the field (NASEM, 2017a). The majority of the studies cluster within the practice area of initiating and managing dispensing systems, such as points of distribution and other modalities for dispensing. This Capability includes the most AARs and case reports among all 15 PHEPR Capabilities (tied with Community Preparedness) and accounts for 87 percent of U.S.-based studies. The predominant

___________________

5 The committee developed a broad list of potential PHEPR practices by breaking the functions and tasks within the PHEPR Capabilities down into topics at a level of resolution for which conclusions about effectiveness could potentially be drawn.

practice area and the numbers of U.S. studies and AARs and case reports are not surprising given that past U.S. preparedness efforts have often focused on enhancing this practice area.

Implications for Future Research and Evidence Reviews

The information gleaned from this scoping review and the series of evidence maps it produced may be useful to policy makers and PHEPR researchers as an important first step for two distinct efforts: (1) clarifying where sufficient evidence may be available for future efforts to synthesize the evidence on the effectiveness of PHEPR practices, and (2) identifying gaps that can inform priorities for future research.

Those practice areas in which quantitative impact studies tend to cluster may be good starting points for considering topics for future evidence reviews, particularly if they can be linked to important knowledge gaps identified by practitioners or policy makers. In a prioritization activity conducted by the committee with 10 PHEPR practitioners, for example, at least 66 percent of the panel indicated that reviews of several topics in Community Preparedness, Emergency Public Information and Warning, and Responder Safety and Health were of highest or high priority (see Appendix A for the full results from this activity). The map of U.S. quantitative impact studies (see Figure 2-3) shows that there is some impact evidence available for each of these three Capabilities. Capability-specific evidence maps provided in Appendix D could help further scope these reviews. For example, the PHEPR practitioner

panel rated effective message formats for information sharing with at-risk populations as a high-priority practice area.

Figure 2-5 illustrates the characteristics of the 66 studies for PHEPR practice areas within the Emergency Public Information and Warning Capability. The map shows no quantitative impact studies for the at-risk population practice area, which may indicate that a review on this topic would yield little in the way of findings on effective practices and suggests that the topic is an important research gap. However, it is important to reiterate that Emergency Public Information and Warning is a broad field, and it is likely that some impact research has occurred outside of PHEPR. Evidence on risk communication practices in other contexts could, for example, be reviewed and synthesized as described in Chapter 3 as “parallel evidence” (i.e., evidence from similar practices used in other fields that could inform determinations of effectiveness).

In terms of research gaps, the evidence maps can aid in determining which areas of research are weakest and strongest. Prioritizing of which areas with little information are most deserving of further research and funding would be most useful if dependent not only on the magnitude of the evidence gaps observed, but also on the type of disaster or emergency and the resources, workforce personnel, and other components of the public health system available to public health agencies.

A LOOK BACK AT PHEPR RESEARCH PROGRAMS

The commissioned scoping review provides a broad overview of the research for the 15 PHEPR Capabilities and specific practice areas within these Capabilities. This section summarizes several of the transformational research programs and initiatives that contributed to the development of this PHEPR knowledge base and advanced PHEPR as a field of study. As a result of these research programs, PHEPR research has evolved in essentially two decades from focusing on program assessment and evaluation, to examining systems and health services, to being conducted during public health emergencies (Carbone and Thomas, 2018). Unfortunately, many of these programs are no longer funded and have been discontinued. As in all areas of public health, ongoing research and evaluation are essential to improving practice in the PHEPR field.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–Funded Academic PHEPR Workforce Development and Research Centers

Centers for Public Health Preparedness

In the PHEPR field, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has long supported academic and practice linkages, particularly with schools of public health (Thielen et al., 2005; Turnock et al., 2010). In 2000, CDC funded four Centers for Public Health Preparedness (CPHPs) within schools of public health. The CPHPs were developed to be practice oriented, and to work closely with public health agencies to assess training needs and deliver competency-based training, education, and technical assistance and provide a nexus for applied research related to workforce development. From 2004 to 2010, CDC expanded the program and provided $134 million to 27 CPHPs to continue enhancing training and education for public health agencies (Baker et al., 2010; Richmond et al., 2010). The CPHPs were instrumental in strengthening academic and practice relationships related to workforce competencies (Wright et al., 2010). Furthermore, the CPHPs set the stage for some of the earliest attempts at developing evidence-based practices for workforce development by evaluating the impact of exercises and trainings and utilizing pre- and posttests to assess knowledge (Alexander et al., 2010; Hoeppner et al., 2010; Kohn et al., 2010; Potter et al., 2010).

Preparedness and Response Research Centers and Learning Centers

It was not until 2006 that provisions in the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA)6 established the need for a research agenda. A 2008 Institute of Medicine (IOM) letter report commissioned by CDC in response to PAHPA drove a focus on four topic areas: enhancing the usefulness of training, improving timely emergency communications, creating and maintaining sustainable response systems, and generating effective criteria and metrics for systems (IOM, 2008). To support the goals of PAHPA, and guided by the 2008 IOM letter report, CDC redirected resources from the CPHP program toward research and established nine Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs) at accredited schools of public health (Turnock et al., 2010). Workforce development activities were continued through 14 Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers (PERLCs).

___________________

6 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act. Public Law 116-22, 116th Cong. (January 3, 2019).

Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers

One of the objectives of the PERRCs was to initiate a PHEPR research enterprise in the form of multidisciplinary centers to conduct research that would enhance PHEPR planning, practices, and policies at the federal, state, local, and tribal levels (Eisenstein et al., 2014; Leinhos et al., 2014). The PERRC program, which was funded from 2008 to 2014, was the first and only U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) program to use a public health systems research approach to investigate and improve the PHEPR system (Qari et al., 2014). Over the 6 years it was funded, $57 million was provided across the PERRC program. The PERRCs supported more than 30 projects, contributed to the development of a group of future public health systems researchers through training for about 200 junior research personnel and more than 30 new investigators (Leinhos et al., 2014), and generated approximately 171 peer-reviewed publications7 (Qari et al., 2019). The observations of Savoia and colleagues (2018) suggest that the PERRCs played a substantial role in the PHEPR research field and that without them, at least half of the existing knowledge base would not have been generated (Savoia et al., 2018).

Many of the PERRCs worked closely with public health agencies and developed their research agendas based on requests from and needs of these agencies, guided by an advisory committee comprising representatives of multiple sectors (Leinhos et al., 2014). The PERRCs engaged an estimated 500 research partners (Savoia et al., 2018). In addition to traditional collaborations within schools of public health, the PERRCs collaborated with nontraditional partners, including academic researchers in schools of engineering, law, and public policy (Eisenstein et al., 2014). For example, systems engineers at the University of North Carolina PERRC applied computer simulation tools to large-scale public health emergencies to demonstrate how modeling can improve public health emergency planning, resource allocation, and decision making (Yaylali et al., 2014).

Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers

The PERLC program, which was funded from 2009 to 2015, also within schools of public health, was built on a decade of activities carried out by its predecessor program, the CPHPs, and carried on the mission of strengthening linkages between academic public health programs and public health practice to improve curriculum development for both workforce development and graduate education for public health students (Richmond et al., 2014). The reduction in the total number of centers (from 27 to 14) and total funding (from $134 million to $34 million) for the PERLCs relative to the CPHPs mirrored reductions in federal funding for state and local health departments for public health preparedness (Qari et al., 2018). The PERLCs were expected to both inform and utilize the work of the PERRCs, and there were several schools where both a PERRC and a PERLC were situated. Similar to the CPHPs, the PERLCs emphasized the evaluation of trainings (Hites et al., 2014). Contributions of the PERLCs to the field include innovative methods for workforce preparedness training (Everly et al., 2014; Griffith et al., 2014; Horney and Wilfert, 2014; McCormick et al., 2014; Olson et al., 2014; Renger and Granillo, 2014; Testa et al., 2014; Uden-Holman et al., 2014; Walkner et al., 2014) and training and preparedness efforts in the community for community coalitions and at-risk populations, including Latino, limited-English-speaking, and tribal populations (D’Ambrosio et al., 2014; Frahm et al., 2014; Levin et al., 2014; Riley-Jacome et al., 2014; Tall Chief et al., 2014; Wiebel et al., 2014). The PERLCs developed more than 800 learning products intended to improve PHEPR workforce readiness and competency (Qari et al., 2018).

___________________

7 A repository of PERRC publications can be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/science/updates.htm (accessed June 23, 2020).

Translation, Dissemination, and Implementation of Public Health Preparedness and Response Research and Training Initiative

To accelerate the translation, dissemination, and implementation (TDI) of promising research findings, tools, and trainings developed by the PERRCs and the PERLCs, CDC provided through the TDI Initiative approximately $9 million in funding for nine awards at schools of public health that previously had hosted the PERRCs or the PERLCs (Qari et al., 2018). As a part of this initiative, awardees developed virtual learning communities, experiential learning approaches, and mechanisms to support the implementation of emergency and response communication tools in public health agencies and of a program to increase use of evidence-based programs in public health agencies (Arora et al., 2018; Baseman et al., 2018; Blake et al., 2018; Documet et al., 2018; Eisenman et al., 2018; Revere et al., 2018; Testa et al., 2018; Van Nostrand et al., 2018). The TDI Initiative revealed several challenges to the translation of research to practice (e.g., understanding of the product and its relevance to practice) and researchers’ efforts to overcome these barriers (NORC at the University of Chicago, 2017). The initiative also demonstrated the need to evaluate the relevance and effectiveness of products developed by the PERRCs and the PERLCs for wider implementation.

Additional CDC Efforts

In addition to the CPHPs, the PERRCs, the PERLCs, and the TDI Initiative, CDC has funded other research awards related to PHEPR. In 2007, CDC’s Office of Public Health Research funded Mentored Research Scientist Development Awards (K01) to provide support for intensive research career development under the guidance of a mentor in areas addressing bioterrorism, other infectious disease outbreaks, and other public health threats and emergencies, among other areas (CDC, 2007). The expectation was that awardees would launch research careers and become competitive for research project grant (R01) funding. Currently, CDC’s Center for Preparedness and Response issues Broad Agency Announcements for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Applied Research to solicit proposals for research funding in several topic areas of interest (CDC, 2018).

Other Federal Disaster Research Programs

Numerous other agencies and departments in the federal government have sponsored disaster research more broadly, some of which relates to PHEPR. In the absence of any single overarching research agenda across these federal efforts, each agency independently identified issues of concern and knowledge gaps to be addressed. In the early 2000s, for example, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which focuses on evidence-based health care, funded PHEPR research related to bioterrorism, vaccine distribution, health care system preparedness and surge capacity, and pediatric disaster preparedness (AHRQ, 2011). This program was discontinued in 2011. Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) funded 4 universities and 45 community partners to conduct research related to the disaster’s impacts (Guidry, 2016) on maternal and child health (Peres et al., 2016), mental health (Rung et al., 2016), and community resilience (Mayer et al., 2015). Other sources of federal disaster-related research funding include the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). Along the same lines, the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, housed within the Uniformed Services University, was founded as a collaboration by five federal agencies—HHS, DoD, DHS, the U.S. Department

of Transportation, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs—to conduct health education and research efforts related to domestic and international disasters (NCDMPH, 2020). As Table 2-1 demonstrates, the system for funding disaster research is highly fragmented and complicated, with each federal stakeholder supporting different aspects of issues related to PHEPR. Furthermore, the diversity and breadth of the federal stakeholders who conduct or support disaster research can make it challenging to coordinate efforts, especially when many of these stakeholders do not have public health as their primary mission.

Specific Efforts to Enhance the Conduct of Research During Public Health Emergencies

Recent years have seen increased recognition of critical opportunities to conduct research during response and recovery that could lead to improved assistance to those affected by the event and inform future PHEPR policy, planning, and practice (Carbone and Wright, 2016). Specific efforts to strengthen the conduct of research during public health emergencies have

TABLE 2-1 Key Federal Stakeholders in Conducting or Supporting Disaster Research

| Federal Stakeholder | Role in Conducting or Supporting Disaster Research |

|---|---|

| Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) | Whole-community preparedness, personal disaster preparedness, protective actions |

| Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) | Access to health care; enhancing health systems for geographically, economically, and medically vulnerable populations |

| National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) | Responder safety and health |

| National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) | Built environment, infrastructure, communities, hazards, standards |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | Environmental health, natural disasters, biodefense |

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) | Natural disasters |

| National Science Foundation (NSF) | Social sciences, engineering, natural hazards, built environment |

| Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) | Regional disaster health response, health security, medical countermeasure enterprise, science preparedness |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) | Food and agriculture safety, antimicrobial resistance, climate change |

| U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) | Epidemiology, medical countermeasure development, biodefense |

| U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) | Counterterrorism, homeland security, critical infrastructure, preparedness, and resilience |

| U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) | Community resilience, housing and community development |

| U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) | Natural disasters |

| U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) | Emergency medical services safety, innovation, and infrastructure |

| U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) | VA facilities and veterans’ health affected by disasters |

| U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | Medical countermeasure law and science |

| U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) | Natural hazards, emergency management, environmental health |

been spearheaded largely by CDC, the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), and NIEHS (Carbone and Wright, 2016; Lurie et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2016).

In 2011, the National Biodefense Science Board (NBSB), at the behest of ASPR, issued a call to action to include scientific investigations as an integral component of disaster planning and response (NBSB, 2011). NBSB provided recommendations to establish a research office under ASPR, a separate Emergency Support Function for research, and a disaster institutional review board (see Box 2-1). In 2012, ASPR convened a workshop, “Scientific Preparedness and Response for Public Health,” to discuss efforts to build the infrastructure necessary to rapidly mobilize relevant research expertise and technology in the context of a public health emergency. Continued progress toward many of these recommendations, which are still critical and relevant today, has been lacking (ASPR, 2012).

Following Hurricane Sandy, HHS secured funding for grants from the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 20138 to conduct research on factors related to individual and community resilience, health care system function, and adverse mental health outcomes (Carbone and Wright, 2016). Around the same time, NIEHS, the National Library of Medicine (NLM), CDC, and ASPR, in collaboration with the National Academies’ Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Disasters and Emergencies, hosted a public workshop to examine strategies and diversified partnerships for enabling methodologically and ethically sound public health and medical research during future emergencies (IOM, 2015). This group also rapidly convened experts during the 2014 Ebola and 2016 Zika outbreaks to develop research priorities (IOM and NRC, 2014; NASEM, 2016). During a 2017 workshop focused on a preliminary examination of the key research findings from the Hurricane Sandy grants, it became apparent that more opportunities were needed to discuss how PHEPR research could best be conducted, interpreted, and implemented (NASEM, 2017b).

Currently, efforts to advance the conduct of research during response and recovery are sustained primarily under the Disaster Response Research (DR2) program, a partnership between NIEHS and NLM (with an interagency working group) (Miller et al., 2016). The DR2 program provides tools, protocols, researcher networks, and training exercises to support the conduct of research in response to public health emergencies as an approach to building capacity in preparedness and response.

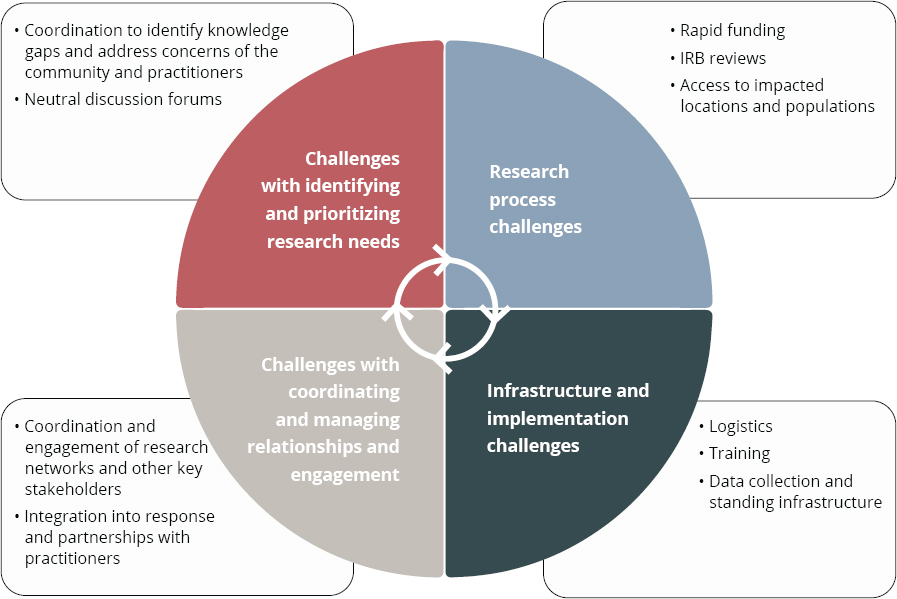

LIMITATIONS OF PHEPR RESEARCH PROGRAMS

As previously noted, the research programs and findings that developed to inform the field over the past two decades have contributed to enhancing the PHEPR knowledge base. Unfortunately, however, the establishment of these programs did not provide a comprehensive solution to the dearth of evidence-based practices for preparing and responding to public health emergencies. This short-lived, uncoordinated approach to funding PHEPR research had several implications for the PHEPR field, discussed below, and left a number of challenges to the conduct of such research unaddressed (see Figure 2-6).

Misaligned and Unclear Research Priorities

The PERRC and the PERLC funding awards were announced before the 2011 publication of the CDC PHEPR Capabilities, which created a misalignment between research and practice. Although the research findings that emerged from the PERRCs and the PERLCs appeared retrospectively to align with the Capabilities, a formal focused and dedicated research agenda with clear goals and measurable objectives aimed at building the evidence base to support the Capabilities was never articulated (Leinhos et al., 2014; Turnock et al., 2010). Furthermore, because a formal research agenda was lacking, researchers often duplicated or recycled similar content (e.g., repeated incident command system trainings), and did not always use appropriate study designs for the research questions being asked. Moreover, the focus on research topics has been uneven, with more than half of the CDC PHEPR Capabilities receiving little to no funding (Keim et al., 2019).

In addition, much of the funding for academic programs (e.g., the CPHPs and the PERLCs) was directed at workforce development, specifically with a charge to develop, deliver, and evaluate trainings instead of conducting research (Kelliher, 2018; Richmond et

___________________

8 Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013. Public Law 113-2, 113th Cong. (January 29, 2013).

NOTE: IRB = institutional review board.

SOURCE: Adapted from Miller et al., 2016.

al., 2014). It was acknowledged that an improved evidence base likely would not emerge from these practice-oriented collaborations (Turnock et al., 2010).

Lack of Infrastructure to Support the Conduct of Quality PHEPR Research

While attempts have been made to advance the conduct of research before, during, and after public health emergencies, continued and sustained progress toward building a research infrastructure to support this approach is lacking. Inadequate infrastructure and supporting mechanisms for the conduct of PHEPR research still encompass a lack of coordination and the inability to prioritize research needs before and during response, varying institutional review board restrictions, Office of Management and Budget issues related to the Paperwork Reduction Act for surveys and user research, lack of a sustainable and rapid funding platform for this type of work, challenges with data collection and rapid mobilization of researchers, and barriers to accessing impacted locations and populations (IOM, 2015; Miller et al., 2016).

Furthermore, the response community remains hesitant to accept researchers within public health emergency settings because of cultural differences between the practice and research fields, and research is not standard practice within the given operational response structure. In a public health emergency, the first priority for a public health agency is to respond and ensure that individuals are removed from harm and continue to receive public

health services (IOM, 2015). Monitoring or assisting in research can strain the resources of a public health agency and its ability to respond. The staff of public health agencies frequently lack the infrastructure or training needed to conduct such research; may lack the time, resources, incentives, or support to collect the necessary data; and may not be authorized to take part in some types of PHEPR research.

Lack of Coordination Across Funders and Shortcomings of Research Funding

The array of federal and nonfederal organizations supporting PHEPR research is highly diverse and complicated, and changes according to the phase of the disaster management cycle on which the research is focused (e.g., preparedness, response, recovery, or mitigation), as well as the type of disaster or hazard (Kirsch and Keim, 2019). This fragmentation further exacerbates the siloed nature of the topics, interests, and goals of PHEPR research, especially in the absence of an overarching national strategy or framework; at the same time, by contrast, PHEPR practice has become a more integrated system after years of collaboration across sectors through diverse responses. Most PHEPR research funding is directed or circumscribed by mission agencies, such as CDC and ASPR, and there are often barriers to using supplemental or programmatic funding for research from such agencies. This situation contributes to discontinuities in funding to support ongoing, sustainable research in the field. Furthermore, the CPHPs, the PERRCs, the PERLCs, and the TDI Initiative were collaborations limited to accredited schools of public health. Although the centers funded by these programs partnered with other disciplines, this approach potentially limited the opportunities for contributions to the evidence base by other relevant disciplines.

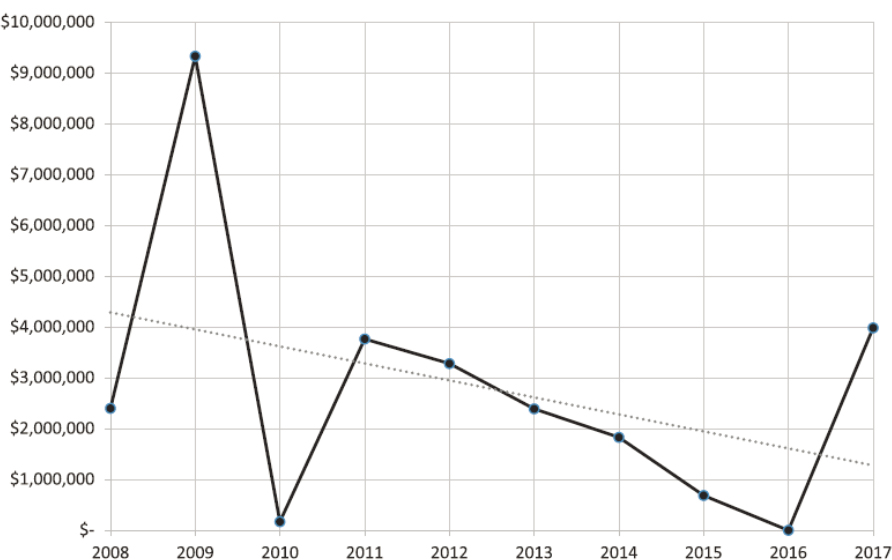

Research follows clear funding streams, and the more durable and long-lasting such funding is, the more focused and extensive is the research. Funding for PHEPR research has historically been short lived, repeatedly stopping and restarting, and has often been reactionary and overly focused on an immediate threat (Keim et al., 2019). The result has been an evidence base comprising one-off interventional studies (i.e., lacking the repetition needed to support strong conclusions about effectiveness). Little funding has been provided for academic PHEPR programs since the end of the PERRCs in 2015, the exception being the Broad Area Announcement for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Applied Research of CDC’s Center for Preparedness and Response. Substantial time and resources were invested in the PERRCs and the PERLCs to advance relationship building and research project development between academia and practitioners. Ultimately, much of that investment was lost when funding cycles were discontinued. Overall, funding for PHEPR research has declined substantially since 2009 (see Figure 2-7). Keim and colleagues (2019) determined that annual funding for research and development for the CDC PHEPR Capabilities from 2008 to 2017 averaged $2.8 million.

Another aspect of PHEPR funding is related to rapid and sustained funding mechanisms for research during public health emergencies (IOM, 2015). Some rapid funding mechanisms are in place (as discussed earlier in this chapter in the section on other federal disaster research programs), but barriers remain, including the narrow focus of research on infrastructure or environmental health, the time required to disburse the funding to researchers, the size of the awards, and the timeframe to complete the research.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Keim et al., 2019.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

To advance the use of evidence-based practices in PHEPR, those agencies responsible for supporting PHEPR planning and implementation will have to take steps to advance the scientific evidence base for these practices. The absence of an overarching framework has contributed to a shortage of coordinated and centralized funding and infrastructure for PHEPR research and a dearth of appropriately trained researchers. Existing PHEPR research funding mechanisms do not align with how a research enterprise is normally coordinated and funded, and there are few incentives to engage in PHEPR research and many barriers to entry into the field, including limited funding opportunities. Should the field continue to be inadequately structured and supported, the PHEPR research enterprise will struggle to improve the quality of research and to address those knowledge gaps depicted in the evidence maps presented earlier in this chapter.

Research needs to become the expectation, not the exception, in the PHEPR field such that individuals are resourced and incentivized to conduct and participate in this research. As new threats emerge and response contexts evolve and become increasingly complex, it is imperative that the PHEPR system be flexible, responsive, and based on evidence to improve practice and save lives in future public health emergencies. Recommendations for ways to improve and expand the evidence base for PHEPR are presented and discussed in Chapter 8.

Conclusion: Funding for and prioritization of research before, during, and following public health emergencies are currently fragmented and disorganized, spread across multiple funding agencies, inconsistent, and do not encourage the progression of quality

research or the sustainable development of research expertise. This situation has contributed to a field based on long-standing rather than evidence-based practice.

Conclusion: With the increasing complexity of both public health emergencies and the PHEPR system, policy makers and practitioners have a crucial need for access to guidance based on robust evidence to support their decisions on practices, policies, and programs for saving lives during future public health emergencies. Therefore, a coordinated and comprehensive approach to prioritizing and aligning research efforts and ensuring that research is relevant and consistently connected to practice, along with investments in research infrastructure, is necessary to strengthen the PHEPR evidence base, thereby ensuring that PHEPR practitioners have the scientific evidence they need to guide and inform their actions. At the same time, PHEPR practitioners will require incentives to base their practices, policies, and programs on evidence.

REFERENCES

Abramson, D. M., S. S. Morse, A. L. Garrett, and I. Redlener. 2007. Public health disaster research: Surveying the field, defining its future. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1(1):57–62.

Acosta, J. D., C. Nelson, E. B. Beckjord, S. R. Shelton, E. Murphy, K. L. Leuschner, and J. Wasserman. 2009. A national agenda for public health systems research on emergency preparedness. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2011. Public health emergency preparedness archive. https://archive.ahrq.gov/prep (accessed February 13, 2020).

Alexander, L. K., J. A. Horney, M. Markiewicz, and P. D. M. MacDonald. 2010. Ten guiding principles of a comprehensive internet-based public health preparedness training and education program. Public Health Reports 125(Suppl 5):51–60.

Arora, M., B. Granillo, T. K. Zepeda, and J. L. Burgess. 2018. Experiential adult learning: A pathway to enhancing medical countermeasures capabilities. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S378–S380.

ASPR (Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response). 2012. ASPR workshop: Scientific preparedness and response for public health emergencies. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/Documents/scientific-prepreport.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

Baker, E. L., M. Y. Lichtveld, and P. D. M. MacDonald. 2010. The Centers for Public Health Preparedness program: From vision to reality. Public Health Reports 125(Suppl 5):4–7.

Baseman, J., D. Revere, H. Karasz, and S. Allan. 2018. Implementing innovations in public health agency preparedness and response programs. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S369–S371.

Birnbaum, M. L., S. Adibhatla, O. Dudek, and J. Ramsel-Miller. 2017. Categorization and analysis of disaster health publications: An inventory. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 32(5):473–482.

Blake, S. C., J. N. Hawley, A. G. Henkel, and D. H. Howard. 2018. Implementation of Florida long term care emergency preparedness portal web site, 2015–2017. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S399–S401.

Carbone, E. G., and E. V. Thomas. 2018. Science as the basis of public health emergency preparedness and response practice: The slow but crucial evolution. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S383–S386.

Carbone, E. G., and M. M. Wright. 2016. Hurricane Sandy recovery science: A model for disaster research. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 10(3):304–305.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2007. CDC Mentored Public Health Research Scientist Development award (K01). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-CD-07-003.html#PartII (accessed February 13, 2020).

CDC. 2018. Research funding opportunity for 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/research/fundingopportunity.htm (accessed February 13, 2020).

Challen, K., A. C. Lee, A. Booth, P. Gardois, H. B. Woods, and S. W. Goodacre. 2012. Where is the evidence for emergency planning? A scoping review. BMC Public Health 12(542).

D’Ambrosio, L., C. E. Huang, and T. Sheng Kwan-Gett. 2014. Evidence-based communications strategies: NWPERLC response to training on effectively reaching limited English-speaking (LEP) populations in emergencies. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S101–S106.

Documet, P. I., B. L. McDonough, and E. V. Nostrand. 2018. Engaging stakeholders at every opportunity: The experience of the emergency law inventory. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S394–S395.

Eisenman, D. P., R. M. Adams, C. M. Lang, M. Prelip, A. Dorian, J. Acosta, D. Glik, and M. Chinman. 2018. A program for local health departments to adapt and implement evidence-based emergency preparedness programs. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S396–S398.

Eisenstein, R., J. R. Finnegan, Jr., and J. W. Curran. 2014. Contributions of academia to public health preparedness research. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 4):5–7.

Elsevier. 2017. A global outlook on disaster science. https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/538091/ElsevierDisasterScienceReport-PDF.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

Everly, G. S. J., O. Lee McCabe, N. L. Semon, C. B. Thompson, and J. M. Links. 2014. The development of a model of psychological first aid for non–mental health trained public health personnel: The Johns Hopkins RAPID-PFA. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S24–S29.

Frahm, K. A., P. J. Gardner, L. M. Brown, D. P. Rogoff, and A. Troutman. 2014. Community-based disaster coalition training. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S111–S117.

Griffith, J. M., S. Kay Carpender, J. A. Crouch, and B. J. Quiram. 2014. A public health hazard mitigation planning process. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S69–S75.

Guidry, V. 2016. Deepwater Horizon research consortia wrap up projects. https://factor.niehs.nih.gov/2016/4/community-impact/deepwater/index.htm (accessed March 5, 2020).

Hites, L. S., M. M. Sass, L. D’Ambrosio, L. M. Brown, A. M. Wendelboe, K. E. Peters, and R. K. Sobelson. 2014. The preparedness and emergency response learning centers: Advancing standardized evaluation of public health preparedness and response trainings. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S17–S23.

Hoeppner, M. M., D. K. Olson, and S. C. Larson. 2010. A longitudinal study of the impact of an emergency preparedness curriculum. Public Health Reports 125(Suppl 5):24–32.

Horney, J. A., and R. A. Wilfert. 2014. Accelerating preparedness: Leveraging the UNC PERLC to improve other projects related to public health surveillance, assessment, and regionalization. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S76–S78.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2008. Research priorities in emergency preparedness and response for public health systems: A letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Enabling rapid and sustainable public health research during disasters: Summary of a joint workshop by the Institute of Medicine and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC (National Research Council). 2014. Research priorities to inform public health and medical practice for Ebola virus disease: Workshop in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Keim, M., T. D. Kirsch, and A. Lovallo. 2019. A comparison of U.S. federal government spending for research and development related to public health preparedness capabilities, 2008–2017. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1–8.

Kelliher, R. 2018. Academic and practice partnerships: Building an effective public health system focusing on public health preparedness and response. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S353–S354.

Khan, Y., G. Fazli, B. Henry, E. de Villa, C. Tsamis, M. Grant, and B. Schwartz. 2015. The evidence base of primary research in public health emergency preparedness: A scoping review and stakeholder consultation. BMC Public Health 15(432).

Kirsch, T. D., and M. Keim. 2019. US governmental spending for disaster-related research, 2011–2016: Characterizing the state of science funding across 5 professional disciplines. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 13(5–6):912–919.

Kohn, S., D. J. Barnett, C. Galastri, N. L. Semon, and J. M. Links. 2010. Public health-specific national incident management system trainings: Building a system for preparedness. Public Health Reports 125(5 Suppl):43–50.

Leinhos, M., S. H. Qari, and M. Williams-Johnson. 2014. Preparedness and emergency response research centers: Using a public health systems approach to improve all-hazards preparedness and response. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 4):8–18.

Levin, K. L., M. Berliner, and A. Merdjanoff. 2014. Disaster planning for vulnerable populations: Leveraging community human service organizations direct service delivery personnel. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S79–S82.

Lurie, N., T. Manolio, A. P. Patterson, F. Collins, and T. Frieden. 2013. Research as a part of public health emergency response. New England Journal of Medicine 368(13):1251–1255.

Mayer, B., K. Running, and K. Bergstrand. 2015. Compensation and community corrosion: Perceived inequalities, social comparisons, and competition following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Sociological Forum 30(2):369–390.

McCormick, L. C., L. Hites, J. F. Wakelee, A. C. Rucks, and P. M. Ginter. 2014. Planning and executing complex large-scale exercises. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S37–S43.

Miake-Lye, I. M., S. Hempel, R. Shanman, and P. G. Shekelle. 2016. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic Reviews 5(1):28.

Miller, A., K. Yeskey, S. Garantziotis, S. Arnesen, A. Bennett, L. O’Fallon, C. Thompson, L. Reinlib, S. Masten, J. Remington, C. Love, S. Ramsey, R. Rosselli, B. Galluzzo, J. Lee, R. Kwok, and J. Hughes. 2016. Integrating health research into disaster response: The new NIH disaster research response program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13(7). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 (accessed June 17, 2020).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Potential research priorities to inform public health and medical practice for domestic Zika virus: Workshop in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2017a. Building a national capability to monitor and assess medical countermeasure use during a public health emergency: Going beyond the last mile: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2017b. Exploring the translation of the results of Hurricane Sandy research grants into policy and operations: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NBSB (National Biodefense Science Board). 2011. Call to action: Include scientific investigations as an integral component of disaster planning and response. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/boards/nbsb/Documents/nbsbrec14.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

NCDMPH (National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health). 2020. National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health. https://www.usuhs.edu/ncdmph (accessed February 23, 2020).

NORC at the University of Chicago. 2017. Evaluation of the translation, dissemination, and implementation of public health preparedness response research and training project. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ASPPH_Media_Files/Docs/CDC_Preparedness_Evaluation_Report (accessed March 3, 2020).

Olson, D. K., A. Scheller, and A. Wey. 2014. Using gaming simulation to evaluate bioterrorism and emergency readiness training. Public Health Reports 20:S52–S60.

Peres, L. C., E. Trapido, A. L. Rung, D. J. Harrington, E. Oral, Z. Fang, E. Fontham, and E. S. Peters. 2016. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill and physical health among adult women in southern Louisiana: The Women and Their Children’s Health (WaTCH) study. Environmental Health Perspectives 124(8):1208–1213.

Potter, M. A., K. R. Miner, D. J. Barnett, R. Cadigan, L. Lloyd, D. K. Olson, C. Parker, E. Savoia, and K. Shoaf. 2010. The evidence base for effectiveness of preparedness training: A retrospective analysis. Public Health Reports 125(Suppl 5):15–23.

Qari, S., D. M. Abramson, J. A. Kushma, and P. Halverson. 2014. Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers: Early returns on investment in evidence-based public health systems research. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 4):1–4.

Qari, S. H., M. R. Leinhos, T. N. Thomas, and E. G. Carbone. 2018. Overview of the Translation, Dissemination, and Implementation of Public Health Preparedness and Response Research and Training Initiative. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S355–S362.

Qari, S. H., H. R. Yusuf, S. L. Groseclose, M. R. Leinhos, and E. G. Carbone. 2019. Public health emergency preparedness system evaluation criteria and performance metrics: A review of contributions of the CDC-funded Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 13(3):626–638.

Renger, R., and B. Granillo. 2014. Lessons learned in testing the feasibility of evaluating transfer of training to an operations setting. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S30–S36.

Revere, D., S. Allan, H. Karasz, and J. Baseman. 2018. Expanding methodologies to identify high-priority emergency preparedness tools for implementation in public health agencies. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S372–S374.

Richmond, A., L. Hostler, G. Leeman, and W. King. 2010. A brief history and overview of CDC’s centers for Public Health Preparedness Cooperative Agreement program. Public Health Reports 125(5 Suppl):8–14.

Richmond, A. L., R. K. Sobelson, and J. P. Cioffi. 2014. Preparedness and emergency response learning centers: Supporting the workforce for national health security. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S7–S16.

Riley-Jacome, M., B. A. G. Parker, and E. C. Waltz. 2014. Weaving Latino cultural concepts into preparedness core competency training. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S89–S100.

Rung, A. L., S. Gaston, E. Oral, W. T. Robinson, E. Fontham, D. J. Harrington, E. Trapido, and E. S. Peters. 2016. Depression, mental distress, and domestic conflict among Louisiana women exposed to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the WaTCH study. Environmental Health Perspectives 124(9):1429–1435.

Rychetnik, L., P. Hawe, E. Waters, A. Barratt, and M. Fommer. 2004. A glossary for evidence based public health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 58:538–545.

Savoia, E., L. Lin, D. Bernard, N. Klein, L. P. James, and S. Guicciardi. 2017. Public health system research in public health emergency preparedness in the United States (2009–2015): Actionable knowledge base. American Journal of Public Health 107(S2):e1–e6.

Savoia, E., S. Guicciardi, D. P. Bernard, N. Harriman, M. Leinhos, and M. Testa. 2018. Preparedness Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs): Addressing public health preparedness knowledge gaps using a public health systems perspective. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S363–S365.

Smith, E. C., F. M. Burkle, P. Aitken, and P. Leggatt. 2018. Seven decades of disasters: A systematic review of the literature. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 33(4):418–423.

Tall Chief, V., T. P. Burton, J. Campbell, D. T. Boatright, and A. Wendelboe. 2014. The Southwest Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Center and the Oklahoma Intertribal Emergency Management Coalition: A unique partnership. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S107–S110.

Testa, M. A., M. L. Pettigrew, and E. Savoia. 2014. Measurement, geospatial, and mechanistic models of public health hazard vulnerability and jurisdictional risk. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S61–S68.

Testa, M. A., E. Savoia, M. Su, and P. D. Biddinger. 2018. Social media learning collaborative for public health preparedness. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S375–S377.

Thielen, L., C. S. Mahan, A. R. Vickery, and L. A. Biesiadecki. 2005. Academic centers for public health preparedness: A giant step for practice in schools of public health. Public Health Reports 120(Suppl 1):4–8.

Turnock, B. J., J. Thompson, and E. L. Baker. 2010. Opportunity knocks but twice for public health preparedness centers. Public Health Reports 125(5 Suppl):1–3.

Uden-Holman, T., J. Bedet, L. Walkner, and N. H. Abd-Hamid. 2014. Adaptive scenarios: A training model for today’s public health workforce. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S44–S48.

Van Nostrand, E., N. Pillai, and A. Ware. 2018. Interjurisdictional variance in U.S. workers’ benefits for emergency response volunteers. American Journal of Public Health 108(S5):S387–S393.

Walkner, L., D. Fife, J. Bedet, and M. DeMartino. 2014. Using a digital story format: A contemporary approach to meeting the workforce needs of public health laboratories. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S49–S51.

Wiebel, V., C. Welter, G. S. Aglipay, and J. Rothstein. 2014. Maximizing resources with mini-grants: Enhancing preparedness capabilities and capacity in public health organizations. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20:S83–S88.

Wright, K. S., M. W. Thomas, D. P. Durham, Jr., L. M. Jackson, L. L. Porth, and M. Buxton. 2010. A public health academic-practice partnership to develop capacity for exercise evaluation and improvement planning. Public Health Reports 125(Suppl 5):107–116.

Yaylali, E., J. S. Ivy, and J. Taheri. 2014. Systems engineering methods for enhancing the value stream in public health preparedness: The role of Markov models, simulation, and optimization. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 4):145–153.

Yeager, V. A., N. Menachemi, L. C. McCormick, and P. M. Ginter. 2010. The nature of the public health emergnecy preparedness literature 2000–2008: A quantitative analysis. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 16(5):441–449.

This page intentionally left blank.