5

Activating a Public Health Emergency Operations Center

Activating a public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) is a common and standard practice, supported by national and international guidance and based on earlier social science around disaster response. Despite widespread use and minimal apparent harms, there is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of activating a PHEOC or of specific PHEOC components at improving response. This does not mean that the practice does not work or should not be implemented, but that more research and monitoring and evaluation around how and in what circumstances a PHEOC should be implemented are warranted before an evidence-based practice recommendation can be made.

Justification for the Insufficient Evidence Statement

Partly because of its long tenure as a common and standard practice, direct research evidence does not focus on whether PHEOCs should be utilized, but rather how they should be implemented. Experiential evidence from a synthesis of case reports and after action reports (from within and outside of public health emergency preparedness and response [PHEPR]) suggests that PHEOCs are probably effective at improving response and may have few undesirable effects in the short term, and speaks to the confidence in the PHEOC model among experienced practitioners across diverse situations. PHEPR practitioners consider activating a PHEOC to be an acceptable and justifiable practice. The feasibility of this practice is variable, and the evidence highlights several feasibility issues to consider before a PHEOC is activated.

Implementation Guidance

Considerations for when to activate public health emergency operations

![]() A public health emergency is large in size and complex in scope. Such events are likely to exceed the capacity of existing resources and/or the capabilities of the agency

A public health emergency is large in size and complex in scope. Such events are likely to exceed the capacity of existing resources and/or the capabilities of the agency

![]() A novel response may require multiple new tasks or partnerships. Err on the side of activating early to handle new tasks or partnerships that may emerge

A novel response may require multiple new tasks or partnerships. Err on the side of activating early to handle new tasks or partnerships that may emerge

![]() An event occurs that requires public health support functions, large-scale information sharing, or response coordination. Consider activating for planned events and environmental disasters with potential for public health implications

An event occurs that requires public health support functions, large-scale information sharing, or response coordination. Consider activating for planned events and environmental disasters with potential for public health implications

![]() Resource, cost, technological, legal, and logistical constraints need to be overcome. Resource needs change throughout an event and may entail moderate to large resources

Resource, cost, technological, legal, and logistical constraints need to be overcome. Resource needs change throughout an event and may entail moderate to large resources

![]() An incident requires high levels of interagency partnership. Even if a response is small, interagency coordination may require PHEOC activation

An incident requires high levels of interagency partnership. Even if a response is small, interagency coordination may require PHEOC activation

Considerations for when to refrain from activating public health emergency operations

![]() The cost of activating is higher than any potential resource needs for the event

The cost of activating is higher than any potential resource needs for the event

![]() Leadership has minimum experience with PHEOC operations, and staff have minimum PHEOC training. Lack of prior activation experience or training could lead to interagency distrust and chain-of-command disruption

Leadership has minimum experience with PHEOC operations, and staff have minimum PHEOC training. Lack of prior activation experience or training could lead to interagency distrust and chain-of-command disruption

![]() Leadership prioritizes maintaining routine public health functions over response needs

Leadership prioritizes maintaining routine public health functions over response needs

Considerations for how to make the decision to activate public health emergency operations

![]() Respect staff knowledge, and involve staff with past emergency experience in leadership discussions

Respect staff knowledge, and involve staff with past emergency experience in leadership discussions

![]() Ensure strong leadership, even using leaders outside the regular hierarchy

Ensure strong leadership, even using leaders outside the regular hierarchy

![]() Provide support to address the social functioning of the PHEOC

Provide support to address the social functioning of the PHEOC

![]() Resource common operating picture functions to increase shared understanding

Resource common operating picture functions to increase shared understanding

![]() Encourage staff flexibility within the PHEOC

Encourage staff flexibility within the PHEOC

![]() Conduct just-in-time training to minimize disruptions caused by less-experienced staff

Conduct just-in-time training to minimize disruptions caused by less-experienced staff

![]() Continuously monitor and evaluate response functions to ensure and prove utility

Continuously monitor and evaluate response functions to ensure and prove utility

DESCRIPTION OF THE PRACTICE

Defining the Practice

The committee examined the evidence on the circumstances in which activating a public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) is appropriate. It also examined various aspects of public health emergency operations (e.g., how response changes following activation). For the purposes of this review, public health emergency operations is defined as the ability to coordinate, direct, and support response to an event with public health or health care implications by “establishing a standardized, scalable system of oversight, organization, and supervision that is consistent with jurisdictional standards and practices and the National Incident Management System (NIMS)” (CDC, 2018, p. 12). Public health emergency operations fall under Capability 3: Emergency Operations Coordination (EOC Capability) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Capabilities: National Standards for State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Public Health (CDC PHEPR Capabilities). Activating a PHEOC allows for relevant public health expertise to be employed and resources to be used that would improve the efficiency and outcomes of a response relative to a response without public health involved. The EOC Capability is closely linked to other CDC PHEPR Capabilities (see Box 5-1).

Under NIMS guidance, an emergency operations center (EOC) is the central location (physical or virtual) where responsible personnel gather to coordinate operational information and resources for emergency operations. More recently, practitioners have used the term PHEOC to define the central location for the strategic management of public health emergencies (WHO, 2015a). Public health agencies typically, but not always, use an incident command system (ICS) within a PHEOC. An ICS is a “scalable, flexible system for organizing emergency response functions and resources characterized by principles such as standardized roles, modular organization, and unity of command” (Rose et al., 2017, p. S130). Many components go into creating a PHEOC, including plans and procedures, physical infrastructure, information and communication technology, systems, and equipment. In addition to these components are PHEOC leaders and staff. This collection of expertise in close collaboration is deemed a core component of a PHEOC.

The process of activating a PHEOC may include, but is not limited to, the following actions:

- conducting a preliminary assessment to determine the need for and level of activation of public health emergency operations (e.g., whether public health will have a lead, supporting, or no role);

- activating necessary public health functions;

- supporting mutual aid according to the public health role and incident requirements;

- identifying personnel with the skills necessary to fulfill the required incident command for activation; and

- establishing primary and alternative locations for the PHEOC and notifying personnel to report either physically or virtually to the PHEOC (CDC, 2018).

Scope of the Problem Addressed by the Practice

Chaos, poor information flow, unexpected tasks, extreme resource needs—these are the factors that often characterize public health emergencies. Standardized, bureaucratic hierarchies, on the other hand, are designed to perform the same tasks repeatedly. Beyond public health, the EOC model was developed in the period after World War II, as civil defense, to address this mismatch and coordinate emergency management’s response to a wide range of emergencies (Botterell and Griss, 2011).

ICS and EOC

ICSs and EOCs are often conflated in response guidance and training, but it is important to differentiate them in any search for an evidence-based approach to their use.

The ICS model—a generic set of flexible, scalable organization structures designed to facilitate integrated response based on military antecedents—was born out of the response to California wildfires in the 1960s. In 1972, an interagency group representing federal, state, and local agencies was convened to address the problem, and eventually developed the Wildfire ICS (Jensen and Waugh, 2014). In 2004, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security established NIMS to provide a consistent, nationwide response approach for all levels of government (Jensen and Waugh, 2014; Rose et al., 2017). The initial release of NIMS mandated training on the ICS model, fostering its official use across U.S. response agencies.

ICS was developed for direct incident management, and its implementation varies. In his distillation of 40 years of research in the area of incident management, social scientist Enrico Quarantelli (1997) cites a still ongoing debate around the implementation and effectiveness

of the ICS model, especially as applied to public health threats (Jensen and Thompson, 2016; Jensen and Waugh, 2014; Rimstad and Braut, 2015; Rose et al., 2017). As a fundamentally hierarchical model, ICS has drawn criticism from scholars with respect to a lack of flexibility and a rigid command and control mentality (Buck et al., 2006). However, it has often been implemented, especially in recent years, with a more intense focus on collaboration and the networked aspects of incident response (Moynihan, 2009). Regardless, the key purpose of any ICS is the direct management of an emergency situation.

By contrast, NIMS is clear that EOCs are structures designed primarily for incident support, decision making, and coordination across a jurisdiction (FEMA, 2017). They may support multiple ICS structures in different geographic and functional regions; they may or may not direct tactical operations. Quarantelli’s (1997) research review points to a “well-functioning EOC” as a key success factor for disaster response. As he notes:

Organised crisis-time activity in a disaster is clearly aided if responding organizations, local and otherwise, are aware of and represented at a common place or location, such as a fully staffed and adequately equipped EOC. (pp. 51–52)

According to Quarantelli, an EOC needs to be primarily a successful social system (rather than a physical one) in order to function well. On the other hand, he does not identify a particular structure (whether ICS or otherwise) as helpful. Having the right people together, collaborating on the correct functions (e.g., evacuation, risk communication) is the key point, as opposed to any focus on organization. In fact, NIMS currently addresses three potential EOC structures without mandating any one of them: an ICS structure modifed to remove its field components, a variant support model focused on communication and resourcing, and a structure that simply mimics day-to-day relationships among government agencies (FEMA, 2017).

PHEOC

The idea of the PHEOC blurs this ICS–EOC distinction, because in a public health emergency, the PHEOC combines the tactical elements of ICS (e.g., for public health operations) with the coordination and decision making of a jurisdictional EOC. For this reason, as well as some skepticism within the medical community regarding the idea of “command and control,” it took some time for public health agencies to adopt an EOC model, although they were often represented in the jurisdictional EOCs described above. For example, it was not until after the 2001 anthrax attacks that CDC developed a PHEOC model for its own public health emergency responses (CDC, 2019). Used during the 2000s in response to severe acute respiratory syndrome, H5N1 planning, and the Hurricane Katrina response, PHEOCs did not become a national focal point for public health responses until the 2009 H1N1 epidemic. Since then, CDC’s PHEOC has been mobilized for more than 17 distinct incidents, from leading roles in major international disease outbreaks such as Zika and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (in progress as of this writing) to support for the response to such nondisease incidents as oil spills and even a mass influx of unaccompanied immigrant children. CDC has credited its PHEOC model with increasing its ability to respond flexibly, increasing the speed of its resource allocation, and improving its leadership model, among other benefits (Redd and Frieden, 2017).

After its massive Ebola response in 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) retooled its emergency response efforts from the top down, adopting a more stringent PHEOC model and a modified version of the ICS framework for global health emergencies. Crucially, both

CDC and WHO have adopted ICS principles (e.g., scalability, defined positions, rigorous training) without the rigid organizational structures of early ICS models. Both organizations now have integrated ICS frameworks that outline the key concepts and essential requirements for maintaining public health emergency operations in an EOC (Rose et al., 2017; WHO, 2015a). At the same time, their models continue to emphasize the key role that adaptability, partnerships, and clinical expertise must play in these events in ways that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), for example, does not. Rose and colleagues (2017, p. S130) suggest that the main purpose of an ICS in a public health context includes

coordination between functional units or groups of expertise within and across organizations; information collection, integration, and sharing internal to the [ICS] but also external to response partners and other stakeholders; developing and disseminating public information and warning and crisis and emergency risk communication messages to target audiences and the general public; and providing access to and deployment of resources such as staff and equipment to an EOC or the field (including the management and logistical support of surge staff).

This functional model, rather than any organizational doctrine, is key to maintaining a focus on health outcomes during the urgency of an emergency.

The Decision to Activate

Today, EOCs may be established at various jurisdictional levels, ranging from local and regional to national or international (WHO, 2015b). Federal and international guidance indicates that EOCs mitigate the impact of emergencies by facilitating an effective, coordinated response. Without these common structures, agencies would need to redevelop their emergency operations procedures with each new incident. This lack of established procedures would likely place stress on the agency and staff responsible for the response. Also, EOCs enable the consolidated movement of substantial resources, which helps emergency managers address the large-scale impacts of incidents (WHO, 2015a).

At the same time, however, the decision to activate emergency operations necessitates careful deliberation, because maintaining and operating an EOC requires the substantial use of finite resources. FEMA has provided general guidance on when to activate an EOC (FEMA, 2019) (see Box 5-2).

The public health emergency response and preparedness (PHEPR) field adds several unique features to the debate about when to activate a PHEOC. These include an ongoing debate about how PHEOCs relate to jurisdictional EOCs. For example, if a jurisdictional EOC is mobilized for a natural hazard (e.g., a hurricane or snowstorm), should a PHEOC be mobilized as well? Or is it better for public health practitioners to deploy to the jurisdictional EOC? Conversely, during an epidemic when a PHEOC assumes response leadership, how should it relate to a jurisdictional EOC that is used to coordinating emergencies of other types? As abstract and bureaucratic as these questions may appear, they have real consequences for health care resourcing, coordinated decision making, and patient care. Different jurisdictions may answer these questions in different ways, but WHO makes it clear that close collaboration is necessary throughout any system of EOCs (WHO, 2015a).

In addition, many public health agencies in the United States are small, and this low-resource status may make PHEOC mobilization difficult, especially since PHEOCs are generally staffed with public health practitioners instead of drawing on multiple agencies, as with jurisdictional EOCs. Thus concerns about resource drain linked to PHEOC mobilization may be especially critical among public health entities. This concern may lead to delayed mobilization of PHEOCs, lessening their utility.

| BOX 5-2 | ACTIVATING AN EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTER |

The jurisdictional policy determines emergency operations center (EOC) activation. The decision-making process for EOC activation should be outlined in a policy. Listed below are possible circumstances that would trigger an EOC activation.

- A Unified Command or Area Command is established.

- More than one jurisdiction becomes involved in a response.

- The Incident Commander indicates an incident could expand rapidly or involve cascading events.

- A similar incident in the past required EOC activation.

- The Chief Executive Officer or similar top executive directs that the EOC should be activated.

- An emergency is imminent (e.g., hurricane warnings, slow river flooding, predictions of hazardous weather, elevated threat levels, major community events).

- Threshold events described in the Emergency Operations Plan occur.

All personnel need to be aware of

- Who makes the decision to activate the EOC.

- What are the circumstances for activation.

- When activation occurs.

- How the level of activation is determined.

SOURCE: Excerpted from FEMA, 2019, p. 1.

Finally, as CDC and WHO have noted, both public health emergencies and the essential practice of public health have unique characteristics that must not be lost during an EOC mobilization (Redd and Frieden, 2017; WHO, 2015b). Clinical and technical expertise, for example, must not be subsumed by bureaucracy. Such key public health functions as prevention services and technical guidance must be represented. Most important, novel public health emergencies are characterized by high levels of uncertainty. The importance of the ability of a PHEOC to adapt both its functions and its structure as new information emerges should never be underestimated. Public health emergency operations must continually evolve, just as the emergencies that they manage do.

OVERVIEW OF THE KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS AND ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

Defining the Key Review Questions

As described above, activating a PHEOC is a common and standard practice in response to a public health emergency. Therefore, the committee approached this review with the objective of better understanding how the PHEPR system interacts with and changes in response to the activation of a PHEOC to inform when and under what circumstances activation should occur. Adopting a systems perspective, the committee posed the following overarching question in this review: “In what circumstances is activating public

health emergency operations appropriate?” To further identify evidence of interest, the committee explored several specific sub-questions related to activation, separate public health emergency operations, changes in response, benefits and harms, and the factors that create barriers and facilitators (see Box 5-3).

Analytic Framework

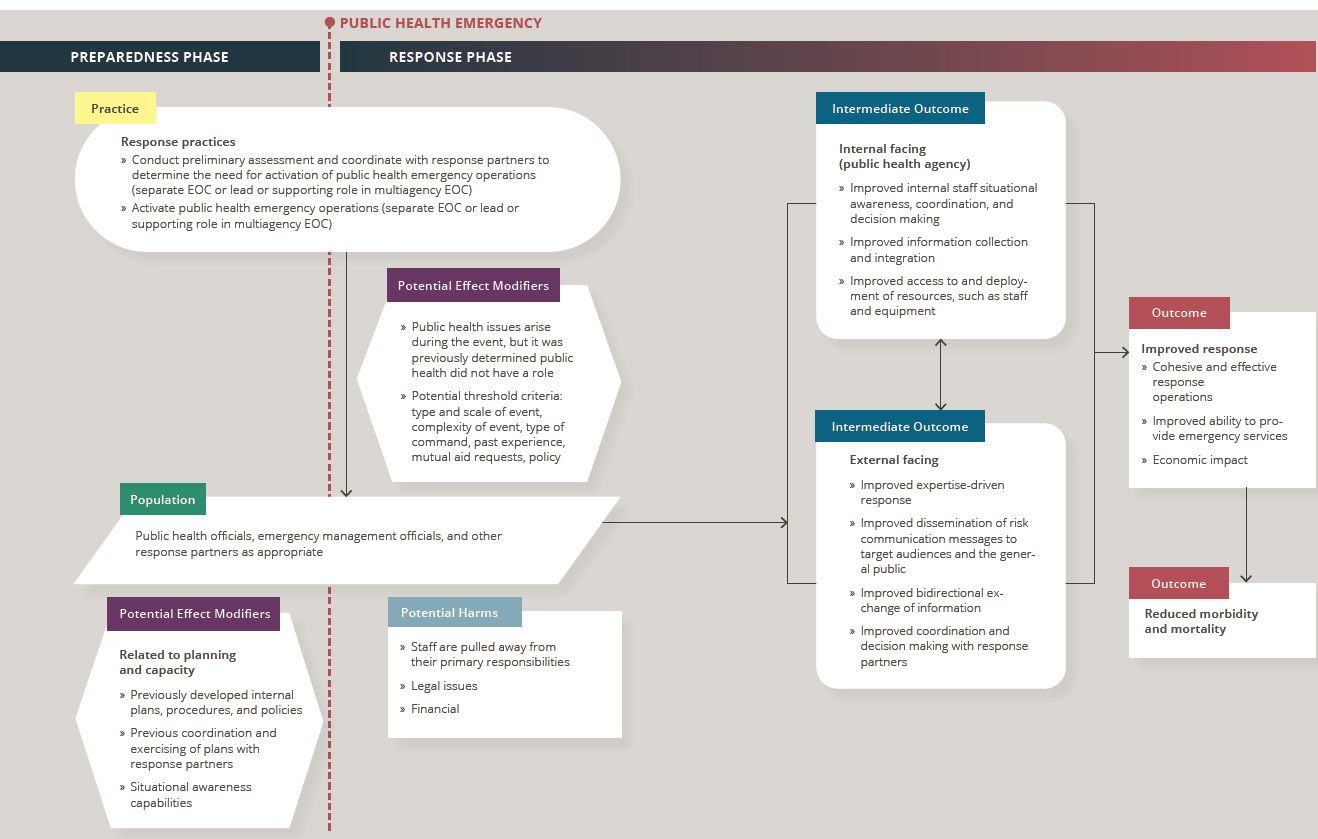

For the purposes of this review, the committee developed an analytic framework to present the causal pathway and interactions between public health emergency operations and its components, populations, and outcomes of interest (see Figure 5-1). The underlying theory is that activating a PHEOC facilitates the coordination of resources and information flow, thereby improving response efforts by increasing the efficiency and timeliness of response (CDC, 2019). As illustrated in the analytic framework, activating a PHEOC or involving public health in multiagency emergency operations should ultimately lead to cohesive and effective response operations and an improved ability to provide emergency services. This improved coordination and more robust service delivery should, in turn, lead to better health outcomes by reducing morbidity and mortality and improving social well-being. Unfortunately, this is a difficult causal pathway to prove.

To begin with, a preliminary assessment in coordination with response partners is required to determine the need for and level of activation, as well as whether public health should assume a lead role, a supporting role, or no role in the emergency operations (CDC, 2018). Deciding whether to activate a PHEOC requires consideration of assigned or recruited staff who may be pulled away from their primary responsibilities, legal issues, and the resources and costs of running the operation. As with many interventions in the PHEPR field, the effectiveness of a response intervention is often measured by intermediate outcomes rather than health outcomes. The committee hypothesized the following intermediate outcomes:

| BOX 5-3 | KEY REVIEW QUESTIONS |

In what circumstances is activating public health emergency operations appropriate?

- What factors (e.g., type and scale of event, type of command, complexity, past experience, mutual aid requests, policy) are useful for determining when to activate public health emergency operations?

- In what circumstances should public health agencies activate a separate public health emergency operations center (PHEOC), lead a multiagency PHEOC, or play a supporting role in a multiagency PHEOC based on identified or potential public health consequences?

- How does the response change following the activation of public health emergency operations?

- What benefits and harms (desirable and/or undesirable impacts) of activation of public health emergency operations have been described or measured?

- What are the barriers to and facilitators of successful public health emergency operations using an incident command center?

NOTES: Arrows in the framework indicate hypothesized causal pathways between interventions and outcomes. Double-headed arrows indicate feedback loops. EOC = emergency operations center.

-

Internal-facing (i.e., public health agency) intermediate outcomes

- Improved internal staff situational awareness, coordination, and decision making

- Improved information collection and integration

- Improved access to and deployment of resources, such as staff and equipment

- External-facing intermediate outcomes

- Improved expertise-driven response

- Improved dissemination of risk communication messages to target audiences and the general public

- Improved bidirectional exchange of information

- Improved coordination and decision making with response partners

OVERVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION1

This section summarizes the evidence from the mixed-method review examining PHEOC activation. Following the summary of the evidence of effectiveness, summaries are presented for each element of the Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework (encompassing balance of benefits and harms, acceptability and preferences, feasibility and PHEPR system considerations, resource and economic considerations, equity, and ethical considerations), which the committee considered in formulating its practice recommendation. Full details on the review strategy and findings can be found in the appendixes: Appendix A provides a detailed description of the study eligibility criteria, search strategy, data extraction process, and individual study quality assessment criteria; Appendix B2 provides a full description of the evidence, including the literature search results, evidence profile tables, and EtD framework for activating a PHEOC; and Appendix C links to all the commissioned analyses that informed this review. Table 5-1 shows the types of evidence included in this review.

Effectiveness

The review identified no quantitative comparative or noncomparative studies or modeling studies eligible for inclusion, but information gleaned from the qualitative evidence synthesis and the case report and after action report (AAR) evidence synthesis contributed to the committee’s understanding of the circumstances in which activating a PHEOC is appropriate. This is a difficult evidentiary situation; the lack of quantitative studies, in particular, speaks to the committee’s high-level finding that more and improved research is needed with respect to this practice. Still, the committee’s overriding goal was to distill the available evidence so as to provide practitioners with the best possible guidance. Therefore, the evidence gleaned was used to construct a high-level view of what happened and what appeared to work. (Refer to Section 1, “Determining Evidence of Effect,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Balance of Benefits and Harms

As stated above, no quantitative research on the effectiveness of PHEOC activation was identified. The evidence from qualitative studies and from case reports and AARs indicates that activation generally results in more efficient response operations and improved ability to

___________________

1 To enhance readability for an end user audience, this section does not include references. Citations supporting the findings in this section appear in Appendix B2.

| Evidence Typea | Number of Studies (as applicable)b |

|---|---|

| Quantitative comparative | 0 |

| Quantitative noncomparative (postintervention measure only) | 0 |

| Qualitative | 21 |

| Modeling | 0 |

| Descriptive surveys | 1 |

| Case reports | 29c |

| After action reports | 35c |

| Mechanistic | N/A |

| Parallel (systematic reviews) | N/A |

a Evidence types are defined in Chapter 3.

b Note that sibling articles (different results from the same study published in separate articles) are counted as one study in this table. Mixed-method studies may be counted in more than one category.

c A sample of case reports and after action reports was prioritized for inclusion in this review based on relevance to the key questions, as described in Chapter 3.

respond to emergent needs with greater flexibility, and as a result may have implicit benefits in relation to improving population health during a public health emergency. The timeliness of response activities also improves because of the increased availability of resources and/or capabilities. Moreover, activation may enable greater access to subject-matter experts during responses with potential public health implications. A long-term benefit of activation is the accumulation of institutional knowledge of what does and does not work (i.e., practical experience) gained by the public health agency under urgent and/or emergent conditions.

Important factors in deciding whether activating a PHEOC will lead to any harms include the potential need for more intensive staffing due to long hours and the need to continue routine public health services, as well as the potential for adaptation-generated interorganizational distrust and chain-of-command disruption. These harms are likely to be present only during an event and not to persist postevent for any appreciable length of time. In some cases, however, such harms may become embedded in the public health system and carry over from event to event (e.g., if a negative interpersonal relationship forms that creates barriers to future successful collaboration). Simply activating a PHEOC is not a comprehensive solution; public health agencies must be ready to manage them effectively, and without that readiness, more harms may be experienced. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 2, “Balance of Benefits and Harms,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Acceptability and Preferences

PHEPR practitioners generally find their roles in participating in emergency operations acceptable and are amenable to the resulting changes in work patterns. PHEPR practitioners prefer to use an ICS but appreciate the ability to modify the structure to better suit their operational context and jurisdiction.

Furthermore, to facilitate the implementation of public health emergency operations, practitioners must believe that implementation of the NIMS and ICS has the potential to

solve real problems and is clear and specific, that incentives and sanctions are not only provided but also likely, and that capacity-building resources are being provided. Ongoing support for meaningful work is important, and PHEOCs that provide this support are therefore likely to be more successful. (Evidence source: case report and AAR evidence synthesis and descriptive survey study evidence. Refer to Section 3, “Acceptability and Preferences,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations

Many barriers impact the feasibility of successful PHEOC activation, and these barriers are often related to challenges involving general management practices. These challenges include interorganizational awareness, relationships, and cultural differences; differences in team members’ knowledge and experience; adequate staffing to implement the activation with all of its components, structures, and processes; communication technology; rules and regulations; the volume of information; and a lack of training in NIMS and ICS, partner roles, and job-specific roles. If these interorganizational characteristics are not conducive to implementation, actual implementation behavior can be negatively impacted regardless of what jurisdictions intend. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis, case report and AAR evidence synthesis, and descriptive survey study evidence. Refer to Section 4, “Feasibility and PHEPR System Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Resource and Economic Considerations

The resource, cost, and logistical constraints of activating a PHEOC are important considerations in deciding whether to activate. These considerations often change over the course of an event and may be sizable depending on the scope of the event. Salient resources include training; databases; supplies; and mechanism(s) for communicating with the public and media, among which is the creation of liaison and point-of-contact positions. These resource needs may dictate the level at which the public health emergency operations should be coordinated (e.g., local, regional, state, and/or national). Baseline PHEOC operations require an infusion of resources beyond normal operations, in general, and public health agencies need to be prepared to manage those costs, ideally with support from other levels of government. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 5, “Resource and Economic Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Equity

Inequities in the implementation of public health emergency operations for different populations due to variability in the availability of resources, infrastructure, and funding likely exist among state, local, tribal, and territorial public health agencies (and are also related to the resource and economic considerations discussed above). Activating a PHEOC can help ensure that the needs of particular at-risk populations are addressed during the response to an event. Accomplishing this requires interagency planning based within the PHEOC that entails establishing a task force to help these population(s), creating a database to collect relevant risk information, providing targeted care in shelters, ensuring access to medications, and addressing specific medical needs caused by power outages and unique transportation requirements. Another approach involves welcoming community representa-

tives into the PHEOC for more inclusive decision making. Additional research is needed to better understand how biases or inequities internal to a PHEOC relate to equitable response outcomes. PHEOCs likely reflect the implicit biases of their decision makers and will support equity more or less well based on the perspective of those individuals. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 6, “Equity,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Ethical Considerations

The section on equity above addresses ethical considerations in PHEOC operations related to the principle of justice or fairness. In addition, the primary ethical principle underlying the initiation of a PHEOC is that of stewardship of limited resources. This principle, often framed as a duty to produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people as efficiently as possible, is frequently seen as particularly important during public health emergencies, because resources in emergencies are typically limited and need to be allocated with care. As a result, ethical concerns related to implementing a PHEOC are centered primarily on the pragmatic benefits and harms of doing so: namely, the possibility that implementing a PHEOC will waste resources and generate harms due to the neglect of other programs while team members are reassigned to PHEOC operations. Some of the procedural principles in play can include transparency, which is supported when a PHEOC improves communication, and proportionality (acting only in proportion to need, or using the least restrictive means to achieve a desired outcome), which is supported when having an activated PHEOC improves situational awareness and therefore averts unnecessary implementation of interventions. (Evidence source: committee discussion drawing on key ethics and policy texts. Refer to Section 7, “Ethical Considerations,” in Appendix B4 for additional detail.)

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The following considerations for implementation were drawn from the synthesis of qualitative research studies, the synthesis of case reports and AARs, and descriptive surveys, the findings of which are presented in Appendix B2. Note that this is not an exhaustive list of considerations; additional implementation resources need to be consulted.

Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC

Establishment of Pre-Event and Ad Hoc Activation Triggers

An essential element of activation of PHEOC activation is determination of the critical point or specific threshold that elicits an activation decision. Having predefined activation triggers is useful in determining when to activate, reactivate, or deactivate response operations. These triggers can be defined in interagency protocols and memoranda of understanding before an emergency event occurs, thus facilitating rapid activation. It is important for such predefined triggers to be flexible and not necessarily rely on a state’s declaration of an emergency, as response needs can still overburden resources in the absence of such a formal declaration. In certain circumstances, particularly novel diseases, new, ad hoc triggers may need to be developed. Five factors may influence the time required to activate a PHEOC:

- previous knowledge and experience;

- the degree to which an emergency event is atypical;

- the amount, speed, and quality of the situation data available;

- the integration of data into building a picture of the situation; and

- perception of the urgency of making a decision.

Triggers can help overcome the hesitation sometimes inherent in PHEOC mobilization based on resource concerns among executive leadership, especially given the finding that practitioners generally consider early PHEOC activation more useful. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 8, “Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Determination of Separate, Lead, or Support Public Health Emergency Operations

Public health agencies appropriately lead a multiagency EOC in response to acute public health threats (e.g., infectious disease outbreaks) when coordination and information sharing among response agencies are critical to the achievement of response objectives. Public health agencies appropriately support a multiagency EOC during planned events or incidents with potential public health implications (e.g., environmental disasters such as oil spills or refinery fires). During such events, public health agencies can help with

- family reunification;

- surveillance and epidemiology, environmental health, and mental health and psychological support functions; and

- mass care and management and distribution of medical supplies.

It is less clear from the evidence when public health agencies should activate fully separate public health emergency operations, although many public health agencies engage in this practice for relatively small epidemics. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 8, “Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Events That Are Large in Size, Complex in Scope, and Novel

It is helpful to activate a PHEOC for multijurisdictional responses to events that are large in size and complex in scope when the event poses threats to public health; it is also helpful to activate early even if the size and scope of an event are initially unknown. There is often a period of initial uncertainty about size and complexity, particularly with regard to novel diseases or events. Risk assessments and foresight can be useful in carefully weighing the potential public health impacts against the cost implications of a resource-intensive activation. In general, the larger, more rapidly developing, and more novel an incident, the more likely it is that a PHEOC structure will benefit a public health agency. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 8, “Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Need for Effective Surge

Understanding the burden of operations required can assist in deciding whether to activate a PHEOC by helping to determine the necessary scope of the activation. If the needs imposed by the incident go beyond the capacity of existing resources, activating public health emergency operations can provide a means for an effective surge response. This is

especially true if public health agencies use the PHEOC mobilization to involve public and private partners that can bring additional resources to bear quickly. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 8, “Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Need for Coordination Among Federal, State, and Local Public Health Agencies

PHEOC activation at the local level is beneficial to support state-level response to public health threats. Activation allows local jurisdictions to keep pace with the response and improves interagency coordination if other agencies are involved. Public health agencies need to clarify the respective roles of the state and local PHEOCs. Doing so is particularly important to ensure clear chains of command and decision-making authority during a response. Regardless of the structure established, public health agencies across the federal, state, and local levels need to work to integrate their functions. In particular, cross-staffing PHEOCs with personnel from public health agencies at all three levels can aid cohesion, as can joint strategic sessions involving leadership at these levels. (Evidence source: case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 8, “Factors in Determining When to Activate a PHEOC,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Other Implementation Considerations

The following conceptual findings inform the perspectives and approaches to be considered when implementing public health emergency operations.

Leverage Strong, Decisive Leadership

During emergencies, strong, decisive leadership is essential despite uncertainties associated with the event. Information will always be imperfect, but indecision that results in taking no action is generally undesirable, because the speed of an emergency magnifies the impact of delay. In addition, leadership needs to have the ability to receive new, sometimes unexpected information and the flexibility to revise objectives as needed. Leadership needs to promote trust by creating a shared sense of purpose and highlighting the contributions of different network members. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Other Implementation Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Create Shared Understanding in Response

A key consideration in the activation of a PHEOC is its ability to aid in building a shared understanding of the incident at hand, as well as the organizational response structure. Flexibility will be successful only if there is a shared understanding of the nature of the response throughout the response structure. Otherwise, staff are likely to reject change, especially when it is rapid.

Cognitively, any time practitioners are involved in a preparedness exercise or an ongoing event, they are creating a shared understanding. Although the picture (or “mental model”) that results from such involvement may exist fully in the mind of one leader, the understanding of the different aspects of an event more often is distributed across multiple leaders and staff. These mental models evolve, and during the chaos of an emergency, they may be quite

different for different aspects of the response. Reality is strained under this kind of chaos, and the mental models of some staff may not reflect the reality of any part of the emergency at all. This is not their fault, but may be due to limited or incorrect information.

One way to think about coordination, then, is to see it as coordination of the varying mental models of staff and leaders within and across agencies. Sharing accurate mental models can lead to a shared understanding of key roles, missions, and needed outcomes, and staff in one location working toward defined objectives can more easily share understanding relative to disparate staff in different locales working under different structures. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Other Implementation Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Ensure Simultaneous Rigidity and Flexibility in a PHEOC

Standard roles and functions likely help increase understanding; however, response decisions must be flexible based on context. This apparent contradiction is, in fact, necessary, and it is important to conceptualize public health emergency operations as command and control functions with the potential to necessitate adjustments to plans and ad hoc improvisations. The often changing, complex, and dynamic environment of an emergency creates unique demands, and preplanned command and control functions may not apply in their entirety. In these situations, it is essential to encourage new organizational structures and functions to meet new needs. Many methods have been used to reconfigure formal structures in emergencies—for example, structure elaborating (building out rapid new organizations such as call centers), role switching (switching to new leadership for new strategic direction), and authority migrating (formally reassigning large portfolios of work suddenly during emergencies). The goal is always to enhance organizational flexibility and reliability (or its perception) during a high-consequence event. At the same time, however, the basic, well-trained PHEOC (or ICS) structures that help to keep the shared understanding operational within the response must remain locked in order to maintain cohesion. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis and case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Other Implementation Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

View Public Health Emergency Operations Teams as Social Groups

To help balance these different demands, it is important to see public health emergency operations teams not just as task groups but also as social groups. Focusing on their social dynamics can help improve relationships and decision-making affinities across different aspects of the response. This social cohesion is a critical factor when a situation is moving too rapidly for the hierarchies involved in standard bureaucratic structures. During the preparedness phase, it can be improved through joint training and exercises and such collaborative activities as planning. However, PHEOCs that can address these social issues during response tend to be more successful as well. For instance, a useful strategy can entail recognizing cultural differences among staff from different organizational cultures and working to bridge those differences. So, too, can being transparent about preexisting social, economic, and political power differentials and addressing them respectfully. In addition, emotional issues, such as the personal safety concerns of staff members, tend to be overlooked during the urgency of an emergency. Encouraging staff to share concerns and then addressing those concerns when possible will improve cohesion. In short, ensuring that a PHEOC will be able to support the social group it creates is an important consideration for successful implementation. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Other Implementation Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Understand How Response Changes Following PHEOC Activation

It is clear from the above discussion that activating a PHEOC will change the response to an event, potentially for both good and ill. Understanding the nature of these changes is an important implementation consideration. Metrics for gauging these changes are thus helpful in determining whether and when to activate.

The Dynes typology, drawn from the emergency management literature, offers one such set of metrics. Organized by tasks and structure, it can be used to classify emergency response into four categories: established organized response (regular task–old structural arrangements), expanding organized response (regular task–new structural arrangements), extending organized response (nonregular task–old structural arrangements), and emergent organized response (nonregular task–new structural arrangements). Building an understanding of how a public health agency’s response might change following PHEOC activation can inform decision-making processes. Coupling that understanding with a tool such as the Dynes typology that delineates adaptation types will likely improve success. It is important to remember that the likelihood of adaptation is highest in the earliest phases of an event, an argument that supports early consideration of PHEOC activation. (Evidence source: qualitative evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Other Implementation Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

Leverage Staff with Past Response Experience

Leveraging the knowledge and experience of staff regarding prior emergencies can be a practical means of determining whether to activate in a particular situation, providing more context than can be gleaned from any written plan and facilitating positive outcomes. This experience can also be helpful during the preparedness phase in the development of effective, context-driven activation triggers. Ensuring that experienced staff participate in activation discussions, even those generally limited to higher-ranking executives, can thus help foster improved decision making. While it is helpful to leverage experienced staff and subject-matter experts early on in an event, it is also important to recognize that overreliance on a few key personnel can lead to staff fatigue. (Evidence source: case report and AAR evidence synthesis. Refer to Section 9, “Other Implementation Considerations,” in Appendix B2 for additional detail.)

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATION, JUSTIFICATION, AND IMPLEMENTATION GUIDANCE

Insufficient Evidence Statement

Activating a public health emergency operations center (PHEOC) is a common and standard practice, supported by national and international guidance and based on earlier social science around disaster response. Despite widespread use and minimal apparent harms, there is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of activating a PHEOC or of specific PHEOC components at improving response. This does not mean that the practice does not work or should not be implemented, but that more research and monitoring and evaluation around how and in what circumstances a PHEOC should be implemented are warranted before an evidence-based practice recommendation can be made.

Justification for the Insufficient Evidence Statement

Partly because of its long tenure as a common and standard practice, direct research evidence does not focus on whether PHEOCs should be utilized, but rather on how they should be implemented. Experiential evidence from a synthesis of case reports and after action reports (AARs) (from within and outside of public health emergency preparedness and response [PHEPR]) suggests that PHEOCs are probably effective at improving response and may have few undesirable effects in the short term, and speaks to the confidence in the PHEOC model among experienced practitioners across diverse situations. PHEPR practitioners consider activating a PHEOC to be an acceptable and justifiable practice. At the same time, the feasibility of this practice is variable, and the evidence highlights several feasibility issues to consider before a PHEOC is activated.

The evidence reviewed demonstrates coverage across multiple agencies and disciplines, strengthening the conclusion that the evidence is likely applicable to agencies beyond those in which PHEOC activation has been evaluated. However, it is important to note that no studies have examined PHEOCs activated by tribal or territorial public health agencies. Additionally, there is concern about the applicability of studies conducted during an exercise to real-world decision making.

Implementation Guidance

While the available evidence does not address whether PHEOCs should be implemented, it does address how PHEOCs should be implemented. The committee offers a set of implementation considerations based on the evidence from qualitative studies and experiential evidence from case reports and AARs to support planning. Based on this evidence, public health agencies should consider the following factors to make more successful decisions regarding the activation of public health emergency operations.

Considerations for when to activate public health emergency operations:

- A public health emergency is large in size and complex in scope. Such events are likely to exceed the capacity of existing resources and/or the capabilities of the agency.

- A novel response may require multiple new tasks or partnerships. Given high uncertainty, an agency should err on the side of activating early to handle new tasks or partnerships that may emerge. Public health emergency operations can always be scaled back.

- An event occurs that requires public health support functions, large-scale information sharing, or response coordination. Such events include, for example, environmental disasters with the potential for short-term and/or long-term public health impacts. In these incidents, the focus should be on providing support and leadership to the jurisdictional EOC. Activation of emergency operations should also be considered for planned events with potential for public health implications.

- Resource, cost, technological, legal, and logistical constraints need to be overcome. Resource needs often change throughout an event and may entail moderate to large resource requirements, depending on the size and scope of the event.

- An incident requires high levels of interagency partnership. Even if a response is small, interagency coordination may require PHEOC activation, especially if a partner agency has mobilized its own EOC structure. An agency should focus on ensuring that other agencies coordinate within the PHEOC to achieve the most shared understanding.

Considerations for when to refrain from activating public health emergency operations:

- The cost of activating is higher than any potential resource needs for the emergency.

- Leadership has minimum experience with PHEOC operations, and staff have minimum PHEOC training. Lack of prior PHEOC activation experience or training could lead to interagency distrust and chain-of-command disruption, which in turn could negatively impact the success of the response.

- Leadership prioritizes maintaining routine public health functions over the needs of the emergency response. A key aspect of this consideration is leadership’s willingness to allow staff to work at or with the PHEOC, possibly for long hours.

Considerations for how to make the decision to activate public health emergency operations:

- Respect staff knowledge, and involve staff with past emergency experience in leadership discussions.

- Ensure strong leadership, even using leaders outside the regular hierarchy if necessary, or switching out established leaders for newer leaders better suited to the flexibility in decision making needed in emergency response.

- Provide support to address the social functioning of the PHEOC.

- Resource common operating picture functions to increase shared understanding across the PHEOC.

- Create an environment that encourages staff flexibility within the PHEOC.

- Conduct just-in-time training to minimize disruptions caused by less-experienced staff.

- Continuously monitor and evaluate response functions to ensure and prove utility.

EVIDENCE GAPS AND FUTURE RESEARCH PRIORITIES

A significant limitation of the evidence for this practice was the lack of quantitative evidence on the effectiveness of activating a PHEOC, a gap that could be addressed if activation were accompanied by targeted monitoring and evaluation (M&E) when feasible. M&E for a PHEOC involves establishing a system for consistently reviewing how a PHEOC is progressing, what needs to be improved, and whether the response goals are being met. This process entails the regular and systematic collection and analysis of data (quantitative, process, or output data, as well as qualitative data) and assessment of the degree to which anticipated outcomes are met (Gossip et al., 2017; USAID, 2020; WHO, 2015a). Ongoing monitoring is critical to generate information for use in evaluations and AARs.

M&E systems, capacities, and capabilities are best created in the preparedness phase to ensure rapid activation in the event of a public health emergency. Establishing an M&E system for a PHEOC, whether within an agency (at a minimum) or at the national level, can enable standard data collection across different events and aid in conducting analyses over time. Quasi-experimental designs could make use of these data to evaluate the effectiveness of PHEOCs. To guide public health agencies (from low resourced to high resourced) in conducting rigorous M&E, future research could initially focus on identifying the key components of a formalized M&E system for a PHEOC. For example, PHEOCs manage public health emergencies via objectives meant to improve population health outcomes. Keim (2013) notes that these objectives can be standardized across responses, which makes it possible to develop objective-driven performance measures that can be adapted and implemented across jurisdictions during public health emergencies. The importance of addressing this gap was also confirmed during the committee’s prioritization of review topics with 10 PHEPR practitioners, at least half of whom indicated that resources and tools are needed to capture

critical information during an emergency that involves public health (see Appendix A for the full results of this prioritization activity).

The committee was unable to identify any quantitative research on the effectiveness of activating a PHEOC. Future research could take advantage of the heterogeneity inherent in the response to a public health emergency and use natural experiments to evaluate PHEOCs (e.g., examining cases in which one agency activates and another does not, or looking at different activations within the same agency). Matched comparison group studies are an example of such a methodology. Additional examples are presented in Tables 8-2 and Annex 8-1 in Chapter 8.

Because there was no quantitative research on the effectiveness of PHEOC activation, the committee relied on other types of evidence, including evidence from qualitative studies, case reports, and AARs, to inform its work on this practice. It will be important for future efforts to focus on ways of ensuring that evaluators adhere to rigorous protocols for data collection, analysis, and interpretation for these types of evidence because they can be useful in particular for topics such as this. Such research could be strengthened through the use of more robust methods, such as qualitative comparative analyses (Baptist and Befani, 2015) and data collection (e.g., routine data captured in a future M&E system). A qualitative comparative analysis is a comparative method that allows evaluators to identify and understand what different combinations of factors are most important for a given outcome and the influence of context on that outcome.

It is important to note that one of the review findings was supported by evidence from only case reports and AARs, which could indicate an issue that has arisen in practice but has not been examined within the context of a research study. This finding was related to the interaction among different PHEOCs at the federal, state, and local levels. The case reports and AARs briefly discuss the importance of activating a PHEOC at the local level to support state-level responses and to improve coordination among the different levels and agencies. The field could benefit from research exploring what is known about the interactions and coordination among various EOCs. Large-scale implementation of PHEOCs is already under way. Therefore, greater investment in implementation science methods and approaches is needed. Implementation science is a rapidly advancing field that is used to help bridge the divide between research and practice. One focus of implementation science is the core components of an intervention. In thinking about adopting a PHEPR practice for implementation in different contexts, identifying its core components can help determine what should remain intact and what can be modified without jeopardizing outcomes. The core components of a PHEOC have not been adequately examined. The lack of a sufficient narrative describing a PHEOC in the corpus of qualitative studies, case reports, and AARs made it difficult for the committee to determine the impact of PHEOC activation. Furthermore, the lack of uniform terminology and insufficient reporting and articulation of methodology hampered consistency in searching and reviewing the literature, especially when the committee was attempting to review public health emergency operations, which involves a fairly new terminology. For example, one jurisdiction’s PHEOC may be another’s command center or ICS. Because public health emergency operations are complicated in that a public health agency may activate separately, lead a multiagency effort, or play a supporting role in a multiagency effort, and are context-specific depending on the jurisdiction, this level of detail and the use of common terminology are critical to future evaluations. Also related to implementation science, no studies examined PHEOCs activated by tribal or territorial public health agencies, a gap the committee believes to be significant in understanding the effectiveness of activating a PHEOC in these contexts. Future research needs to make a point of seeking out best practices in these areas.

More broadly, the committee acknowledges the limitations of its evidence review methodology in reviewing the practice of PHEOC activation. Methods used in other fields, such as the behavioral, organizational, structural, and quality improvement fields, could be employed to better understand PHEOC functioning. Decision trees, systems dynamics, systematic expert opinion methodologies such as Delphi, and other methods could be beneficial in informing those circumstances in which to activate a PHEOC. At the time of this writing, the COVID-19 pandemic was occurring, and many public health agencies had activated PHEOCs at differing times and levels to respond. The COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity to examine the timing of PHEOC activations and compare the benefits and harms of differing activation approaches. Several key gaps in current research and practice could immediately be observed: (1) the need for evidence on the impact of sustaining activation for a long period, (2) the importance of having an M&E system in place prior to an emergency to enable the collection of data on PHEOCs during an actual emergency, and (3) the need to understand the interrelationships of activation and scalability. In a true catastrophe, the question is not just mobilization of a PHEOC, but the scale at which that mobilization occurs and the PHEOC’s ability to improvise new functions as needed in response to shifts in the situation. During and following the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be crucial to coordinate research efforts to ensure that priority questions related to public health emergency operations are answered with appropriate and rigorous methods (see Chapter 8 for additional detail regarding methodological improvements).

REFERENCES

Baptist, C., and B. Befani. 2015. Qualitiative comparative analysis: A rigorous qualitative method for assessing impact. Coffey International. https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Qualitative-Comparative-Analysis-June-2015%20(1).pdf (accessed March 12, 2020).

Botterell, A., and M. Griss. 2011. Toward the next generation of emergency operations systems. Paper read at the 8th International Information Systems for Crisis Response And Management (ISCRAM) Conference, Lisbon, Portugal.

Buck, D. A., J. E. Trainor, and B. E. Aguirre. 2006. A critical evaluation of the incident command system and NIMS. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 3(3).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2018. Public health emergency preparedness and response capabilities: National standards for state, local, tribal, and territorial public health. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/capabilities.htm (accessed March 12, 2020).

CDC. 2019. CDC Emergency Operations Center. https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/eoc.htm (accessed March 22, 2020).

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). 2017. National Incident Management System: Third edition. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1508151197225-ced8c60378c3936adb92c1a3ee6f6564/FINAL_NIMS_2017.pdf (accesed May 20, 2020).

FEMA. 2019. Lesson 7: Activating and deactivating the EOC. https://emilms.fema.gov/IS2200/groups/323.html (accessed April 1, 2020).

Gossip, K., H. Gouda, Y. Y. Lee, S. Firth, R. I. Bermejo, W. Zeck, and E. J. Soto. 2017. Monitoring and evaluation of disaster response efforts undertaken by local health departments: A rapid realist review. BMC Health Services Research 17(450).

Jensen, J., and S. Thompson. 2016. The incident command system: A literature review. Disasters 40(1):158–182.

Jensen, J., and W. L. Waugh. 2014. The United States’ experience with the incident command system: What we think we know and what we need to know more about. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 22(1):5–17.

Keim, M. E. 2013. An innovative approach to capability-based emergency operations planning. Disaster Health 1(1):54–62.

Moynihan, D. 2009. The network governance of crisis response: Case studies of incident command systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19(4):895–915.

Quarantelli, E. L. 1997. Ten criteria for evaluating the management of community disasters. Disasters 21(1):39–56.

Redd, S. C., and T. R. Frieden. 2017. CDC’s evolving approach to emergency response. Health Security 15(1):41–52.

Rimstad, R., and G. S. Braut. 2015. Literature review on medical incident command. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 30(2):205–215.

Rose, D. A., S. Murthy, J. Brooks, and J. Bryant. 2017. The evolution of public health emergency management as a field of practice. American Journal of Public Health 107(S2):S126–S133.

USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development). 2020. Unit 9: Monitoring and evaluation. https://sbccimplementationkits.org/sbcc-in-emergencies/lessons/unit-9-monitoring-and-evaluation (accessed May 20, 2020).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015a. Framework for a public health emergency operations centre. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/196135/9789241565134_eng.pdf;jsessionid=931A229892C8BD19F6B995B37FE0325F?sequence=1 (accessed March 12, 2020).

WHO. 2015b. Summary report of systematic reviews for public health emergency operations centres: Plans and procedures; communication technology and infrastructure; minimum datasets and standards; training and exercises. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/197379/9789241509787_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed March 12, 2020).