5

The Role of the Regulatory Agency

The two previous chapters in this report considered distal influences on the regulatory system: actions at the global level that can encourage product safety and how decisions made at higher levels of government can affect the ability of the regulatory agency to function. This chapter considers tasks that are, for the most part, within the control of decision makers at the regulatory agency. It also sets out some principles regulators can use to ensure their invariably limited resources are being deployed efficiently.

The strategies put forth in this chapter aim to increase the scientific credibility and efficiency of regulatory agencies. Risk is the best guiding principle to lead the agency to this goal. Chapter 2 described the continuous risk management cycle through which agencies are constantly identifying risks and ranking the risks of varying complexity and certainty (IOM and NRC, 2010a). This chapter discusses a range of risks facing regulatory agencies, especially in low- and middle-income countries, as well as strategies to mitigate these risks.

STRATEGIES FOR MANAGING RISK

A 2010 report from the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council, Enhancing Food Safety: The Role of the Food and Drug Administration, set out the attributes of a risk-based food safety system (see Box 5-1), all of which are sufficiently general that they apply to medical products as well. Reliable data are part of such a system, as is the technical depth at the agency to make good use of data. Without reliable and accurate data, shared promptly and through secure means, no agency can

understand the risks facing it or even begin the iterative process of risk ranking and intervention.

At the same time, the committee recognizes that an over-emphasis on the ideal risk analysis can be a barrier to progress in low- and middle-income countries. In reality, decisions on how to reduce risks, even at the most advanced agencies, are made in the face of uncertainty. When time or resources are constraints, a narrative or qualitative risk analysis may be the best strategy (Paoli, 2010). While the inferences drawn from narrative or even semi-quantitative data are not as strong as probabilistic inferences, less quantitative assessments can be done faster and at lower cost (Paoli, 2010).

Therefore, risk-based approaches are appropriate in low- and middle-income countries’ regulatory agencies, recognizing that the perfect need not be the enemy of the good. While acknowledging that the public sector is often limited in its data and capacity for analysis, regulators can still use a risk-based approach to understanding and making use of the information they have.

Furthermore, the risk-based framework, even when applied with imperfect data, draws attention to the relative vulnerabilities in a country’s system (Babigumira et al., 2018). Understanding these weak spots is essential for the proportional allocation of resources that helps countries transition off donor funding (Babigumira et al., 2018).

Some evidence suggests that the risks facing a country will vary with economic development. For example, increasing income and urbanization bring about new risks as the distance between farm and table grows and diets become more diverse (Jaffee et al., 2019). Microbial contamination, for example, is more of a problem as people eat more animal-source foods requiring refrigeration; as people take more meals outside the home they are exposed to more and different food-handling risks (Jaffee et al., 2019). Different populations within a country can face different risks, especially in middle-income countries, which bear a dual burden of naturally occurring hazards, such as mycotoxins, and those associated with modernizing systems and increased processing, such as microbial and chemical contamination (Jaffee et al., 2019). In considering the medicines market, the relative openness of a country’s borders can affect the risk of falsified or substandard medicines in its market (Babigumira et al., 2018).

Effective Use of Data

The effective use of data is a critical bottleneck to agencies’ scientific rigor and risk-based decision making (IOM, 2012). Part of the challenge in collecting data is knowing how to monitor the market; not all product safety events are equally important to the regulatory agency. In considering how to collect data, it is important to identify risks that occur frequently

enough to produce data; events where past risks are predictive of the future, making them useful for predictive modeling; and where a baseline may be established. Information about foodborne disease outbreaks, inspection reports, and records of previous regulatory action such as recalls would meet these criteria. There are also questions of access, if, for example, data will be entered manually or pulled from automated sources. An important first step to better information management is for the agency to take stock of the data produced in its routine monitoring programs and to assess its usefulness. Then, if necessary, the agency can consider various strategies to improve the data available. For example, 2018 guidance from the Promoting the Quality of Medicines program made the distinction between sporadic quality surveys of medicines in the market, and a predictable, strategic post-market surveillance system (Kaddu et al., 2018).

Epidemiological data are useful for regulatory agencies. They are a direct measure of public health consequences, and there are often at least nascent systems in place to collect it (WHO, 2017b). Expressing health outcomes in terms of quality or disability-adjusted life years allows for valid comparisons to other health programs (Babigumira et al., 2018). At the same time, links between epidemiological data and regulatory problems can be tenuous at best. Foodborne illness in particular is under-reported, even in places with sophisticated surveillance and reporting systems (Jaffee et al., 2019). In the case of poor quality medicines, the relationship between a death or illness and a contaminated product may be even more obscure as medicines are usually given to people who are already sick, clouding the relationship between cause and effect (IOM, 2013).

Over the last few years, the analysis of big data (the large amounts of data produced in digital interactions) has been promoted for its promise to improve health and livelihoods around the world (Bresnick, 2019; Raghupathi and Raghupathi, 2014; Serra, 2016). Big data, which includes information drawn from manufacturing, health services, business, and government agencies (to name a few), has particular promise for low- and middle-income countries, where even estimating the scope of food and medicine safety problems is a challenge (Serra, 2016; Wyber et al., 2015). Most vertical health programs collect considerable information from health workers (Wyber et al., 2015); manufacturing and government records are similarly rich in data.

The promise of technology to reduce the cost of aggregating and collecting data is especially valuable when resources are scarce. In a joint statement on food safety and trade, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Trade Organization (WTO) praised the promise of big data to facilitate trade, improve traceability and safety, and allow the food system to respond to various threats (FAO et al., 2019). Savings on transaction

costs add up, especially for perishable food. A 1 percent savings on transaction costs, when magnified over the supply chain, yields a benefit of $43 billion (FAO et al., 2019). But realizing these benefits requires cooperation within and among countries, as well as cooperation with the private sector and academia (FAO et al., 2019).

Data sharing is an intermediary on the way to realizing the potential of big data. Research on data sharing in low- and middle-income countries is promising; for the most part, scientists support data sharing to advance science and collaboration, as well as for networking and visibility (Bezuidenhout and Chakauya, 2018). This is consistent with the emerging global consensus in favor of data sharing, though this consensus has yet to translate into widespread practice (Bezuidenhout and Chakauya, 2018; Cheah, 2019; Waithira et al., 2019). In places where reliable electricity, connection speed, and processing power cannot be taken for granted, support for data sharing or big data can seem overly ambitious (Bezuidenhout and Chakauya, 2018). Because of problems with management and weak health systems (of which the regulatory system is just one part) the promise of modern data analytics has remained out of reach in low- and middle-income countries (Wyber et al., 2015). The irony of the problem remains: When food and drug safety problems are more common, the tools to understand them are more valuable, but scarce (Waithira et al., 2019). Despite growing support for data sharing, there are “few incentives and multiple barriers” to its implementation (Hajduk et al., 2019). The main obstacles to data sharing in low- and middle-income countries, especially for regulatory agencies, are not clear and may be a question for the proposed Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science (Bezuidenhout and Chakauya, 2018). Research in the United States has found data governance to be the biggest barrier (Poole and Harpel, 2018). It is also possible that the mechanism for data sharing (e.g., the use of automated collection systems or secure online sharing) may be an important barrier in less developed countries. Box 5-2 describes a program that aims to remove such barriers for clinical trials researchers in sub-Saharan Africa.

The private sector is often reluctant to share data; they may fear that information in their internal reports introduce liability or damage their reputation (Narrod et al., 2019b). Concerns about the direct costs associated with data sharing are also common (Narrod et al., 2019a,b). Blinding or aggregating data, possibly with a university or other trusted third-party acting as intermediary, is one way around this barrier (Narrod et al., 2019a).

Another common barrier when sharing information with the private sector is a company policy at odds with that of the regulatory agency. For example, pharmaceutical companies often have their own teams investigate reports of falsified and substandard medicines (Access to Medicine Foundation, 2018). Companies are obliged to confirm cases and report them

to the local regulatory authority or to the WHO within 7 days (Access to Medicine Foundation, 2018). Nevertheless, a 2018 survey of 20 large firms found that only 35 percent followed these guidelines (Access to Medicine Foundation, 2018).

Regulatory agencies should give special attention to their data policies (Waithira et al., 2019). This includes the models they will use (options range from online open databases to managed access via application), their confidentiality restrictions, and processes for resolving disputes (Poole and Harpel, 2018; Waithira et al., 2019; Wyber et al., 2015). Clarity regarding the rules for data sharing can encourage more stakeholders to be comfortable with it, ultimately building relationships, especially with the industry stakeholders whose participation is vital (Poole and Harpel, 2018). At the same time, there are circumstances where industry representatives will

object to information sharing because of confidentiality concerns. It is important to provide industry with both reasons for sharing and a motivation to do so (Narrod et al., 2019b). Regulators can prepare for a potential conflict by highlighting in the data-sharing policy their standards for public transparency, making clear that the health of the public takes precedence over any commercial interests.

Scarce resources are valuable, and data used to monitor food and medical product safety can be scarce, especially for regulatory agencies. Data sharing can help overcome this scarcity. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget’s recent direction to heads of agencies and departments framed data sharing and management as stewardship of the taxpayers’ money, encouraging them to harness existing information to answer policy questions (Vought, 2019). This first step in this process may be taking stock of which other agencies or private-sector organizations might already have the information they need, and if they are willing to share it. When food safety responsibilities are divided between the ministries of health and agriculture, as in the United States, a strategy for cooperation can help avoid redundant work and maximize the value of information. Businesses also collect valuable information from across their supply chains, information that would help regulators identify potential risks and areas to concentrate their resources (Harkins, 2016). As Malcolm Harkins explained in Managing Risk and Information Security, “Because threats spread so quickly and the threat landscape is so complex, it is hard for any single organization to gain a clear view of all potential vulnerabilities, threats, and attacks. External partnerships can help. They provide additional intelligence that we can use to improve our [security]” (Harkins, 2016).

But sharing sensitive information is difficult for all parties. Public–private partnerships can be effective means for data sharing (Narrod et al., 2019b). Novel information-sharing technologies, though not a substitute for building trust, also have potential to help overcome this problem (Knowledge@Wharton, 2018).

Distributed Ledger Technology

Distributed ledger technologies (of which blockchain is one type) are databases that are synchronized across different computers, with certain participants in the system having the authority to update the entire network (Pisa and McCurdy, 2019). Systems can be described as either permissioned or permission-less, depending on the authorization for updating them (Pisa and McCurdy, 2019). These databases hold more information, more securely than other data management systems (Verhoeven et al., 2018). And, because there is no central database or single person in charge of the system,

the administrative costs of collecting and managing data are greatly reduced (Verhoeven et al., 2018).

Distributed ledgers have particular promise for managing complicated supply chains. Tracing ingredients through a supply chain could allow for quick pinpointing of where contamination occurs; it could be used to verify label claims, or to better understand patterns of supply and demand, helping procurement officers avoid shortages or waste (Pisa and McCurdy, 2019). But there are still questions as to what range of network sophistication lends itself to distributed ledgers (Knowledge@Wharton, 2018). Experts have cautioned against the overuse or novelty appeal of such technology, especially in low- and middle-income countries where the cost of distraction could be high (Knowledge@Wharton, 2018). At the same time, the IBM Food Trust is using blockchain technology to allow farmers, processors, or any food supplier to share data with their networks (IBM, 2019; Knowledge@Wharton, 2018). Through the use of an online app that feeds into a blockchain system, farmers can send information about their produce to buyers, reducing the time needed to trace a supply chain from about a week to seconds (Knowledge@Wharton, 2018).

The realities of modern manufacturing have made supply chain traceability a priority for regulatory agencies around the world, but traceability programs produce massive amounts of data that can be difficult to manage (Pisa and McCurdy, 2019). It is important to set the groundwork now to make use of those data. An investment in data and their management will pay off in better knowledge of vulnerabilities in the supply chain and information on waste, surplus, supply, and demand. (Box 5-3 describes how advanced data analytics helped the U.S. Department of Agriculture target its food inspections.) These are the same data that inform procurement and should therefore be especially high priority in the middle-income countries projected to graduate from multilateral procurement over the next 20 years (Pisa and McCurdy, 2019; Silverman, 2018).

Assessing Health and Economic Effects of Regulation

A strong regulatory system protects public health and also has positive spillovers for the economy. A poorly designed system obviously has disastrous implications for health; it can also lower growth, create market confusion, and reduce competition. Nevertheless, estimating these effects is challenging. There are many intermediaries between a good regulatory practice, say public consultation on rules, and gross domestic product growth (Parker and Kirkpatrick, 2012). Even measuring the health effects is not direct. Except in crises, when a product safety failure has caused obvious illness or worse, it is difficult to say what portion of health improvement or economic growth can be credibly attributed to the regulatory

system. This presents a dilemma for regulators, because that is precisely the analysis that would be most compelling to their ministers.

There is a time lag between a regulatory policy going into effect and measurable changes taking place (Narrod et al., 2019b). Analysis of the casual chain between a policy and its health or other effects is one tool to overcome this gap (Parker and Kirkpatrick, 2012). Cost-benefit analysis—the estimating of direct and indirect costs and benefits associated with regulatory policies—can be helpful (Parker and Kirkpatrick, 2012). The problem remains, however, that the technical skill to perform such economic evaluations will not always be available in-house at a regulatory agency. The proposed Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science could take on these analyses when necessary. The regulatory agency can also facilitate good analysis by clearly stating in the goal of regulatory policy the evidence that will be evaluated and sources of this evidence, as well as indicating how the effects of a policy might influence various sub-populations (Jessup, 2013). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) guidance on Regulatory Impact Analysis will be a valuable resource in setting up such assessment, as is the U.S. government primer on the topic (OECD, n.d.-b; Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, 2011). Useful examples of such analyses can also be found on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website (FDA, 2019).

Public–private partnerships are another important means to build capacity for food and medicine safety; such partnerships have potential to ease data sharing and build trust among various partners. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation’s Partnership Training Institute Network involves regulators and private sector participants in trainings to advance a shared goal of improving food safety (APEC, 2018). The World Bank’s Global Food Safety Partnership (GFSP) also brings together government, industry, and academic experts to build capacity for food safety (GFSP, n.d.). GFSP and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization recently began an extensive capacity building program for managing downstream food suppliers in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East (UNIDO, 2016). Research pharmaceutical companies are also increasingly involved in capacity building and in partnerships for research in low- and middle-income countries, with the goal of increasing access to medicines (Hogerzeil et al., 2014; Stevens et al., 2017).

Communication

A unique challenge facing regulatory agencies is that their job, when done well, is invisible. Effective medicines are not praised in stemming an outbreak any more than a restaurant critic would laud food for being uncontaminated. In the inevitable balancing against other flashier pieces of the health system, the regulatory agency stands to lose. For this reason, regulators need to advocate the importance of their work—to their ministers, to industry, and to the public. It is difficult during quiet times to explain to these audiences why support for regulatory agencies is so important. Therefore, crises present an important opportunity for education and advocacy.

Classically characterized by “a threat, a short decision time, and surprise,” more modern definitions of crisis emphasize a threat “to the basic structures or fundamental values of a system” (Boin et al., 2005; Hermann, 1969). By either definition, crises affecting food and medical products have hit all countries in the last decade, raising fundamental questions about the adequacy of government regulatory efforts. Contaminated spinach, toothpaste, blood thinners, infant formula, peanut products, and compounded medicines have raised alarm in the United States and abroad (Andrews, 2012; Bloomberg News, 2019; Browne, 2018; Greenemeier, 2008; Harris, 2006; Reuters, 2007). Other crises are based more on fear than actual evidence of harm, as when the FDA had to address the safety of apple juice

after low, naturally occurring levels of arsenic were identified (Anderson, 2011).

There are serious economic consequences to product safety crises that reach the level of a recall. Grocery Manufacturers Association estimates put the direct cost of a food recall around $10 million to the company alone (Ostroff, 2018). Estimates of the cost of medical product recalls are harder to come by, but a recent study by McKinsey & Company found that medical device recalls could cost a company between $250 and $600 million (Fuhr et al., 2013). Such estimates do not even begin to account for the cost to a company’s reputation or to the damage to markets wrought by loss of confidence in public institutions.

Product safety crises offer a chance to strengthen regulatory infrastructure. The distinction between the sort of crisis that undermines the agency and that which causes people to rally behind it are not always clear, but it seems that strong, effective public communication can make the difference between an embarrassing debacle and grateful support for the agency. For example, when an antimicrobial agent called the Elixir Sulfanilamide was found to be contaminated in 1937, the FDA sent inspectors across the country to track down and dispose of the dangerous product. Instead of blaming the FDA for letting the crisis happen in the first place, the public cheered the agency’s dogged pursuit of risky medication. Momentum from the agency’s success led to the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act the next year (Sharfstein, 2018).

Effective communication during a crisis requires preparation. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Crisis and Emergency Risk Communications manual sets out a series of capabilities needed for accomplishing these goals effectively (CDC, 2014). The FAO has a similar handbook for communicating food risks (FAO and WHO, 2016). Key principles include understanding the audience and the stress the crisis situation has wrought as well as simple, honest messages, including a frank assessment of any uncertainty (CDC, 2014; FAO and WHO, 2016). It is important that crisis communication start as soon as the problem becomes evident, with trained staff clearly and publicly explaining what is known and unknown about the situation, ideally including concrete recommendations as to how people can protect themselves.

Social media are an important route for these communications. Agencies can participate in popular social networks, such as Twitter, with accounts designed for information about recalls and other emergencies. The FDA Twitter account @FDArecalls is an example of such an account (FDA, 2008). Agencies should also respond to misinformation on social media within the same channel, so that someone who sees misleading information on Facebook, for example, can access the correct information from the agency on the same site.

Crises present a unique opportunity because they bring a spotlight onto the regulatory agency. The tragedy of the product safety failure is only compounded if the agency fails to use that spotlight as impetus for change. For example, in 2010 there was a salmonella outbreak from contaminated eggs in the United States (CDC, 2010). FDA leaders, by virtue of careful preparation and knowledge of their risks, were able to segue the attention from the outbreak into support for the Food Safety Modernization Act (Sharfstein, 2018). Internal preparation, and continued, ongoing communication regarding the risks facing the agency can help an agency’s leaders prepare for such a situation.

An agency’s crisis communication plan is, in many ways, an outgrowth of its routine communication. An outreach strategy during an outbreak must start from a routine communication strategy, drawing on existing relationships. Routine communication on the agency’s work, through public consultations, for example, encourages connection with industry and with private citizens (OECD, 2016, n.d.-a; WBG, 2010). Regulators need to recognize the value of public consultations by responding to comments received and explaining the rationale for accepting or rejecting them (OECD, 2016). Such ordinary communication creates a culture of openness that is even more important given the challenges of misleading information circulating via the Internet and social media.

The Internet and social media are invaluable for outreach and education, both critical responsibilities of the regulatory agency. Agencies now have access to a wide range of tools to inform the public about everything from how to cook a chicken safely to where to file an adverse event report. These different platforms are important to integrated health promotion strategies, as is coordination with other public health agencies. Agencies can also choose to receive information from the public through text messages, Twitter, and other platforms. Such communication has a democratizing effect on both knowledge and engagement.

At the same time, social media can be a vehicle for misinformation (Meserole, 2018). Agencies are increasingly called upon to combat such misinformation and may need to work through the same networks spreading the falsehoods (Jaffee et al., 2019; Larson, 2018; Lau et al., 2012).

Furthermore, a great deal of regulatory work is highly technical and complicated, itself a barrier to public appreciation for it. Good manufacturing practices, critical control points, and quality specifications are not usually defined in ways that are easy to understand. As a result, the media, legislators, and the public may not appreciate the need for greater investment in the regulatory agency as a way to protect and promote health.

Given the challenges currently affecting regulatory agencies, it is necessary to re-evaluate the risks facing them. When regulators do this, they should give particular attention to the data systems that help them manage

risks, the work they share with international partners, building internal capacity, and communication.

Recommendation 5-1: National regulatory authorities should take a risk-based approach to the regulation of food and medicines. This includes:

- Developing effective data systems to systematically identify areas of greatest risk;

- Participating in research, data-sharing, technology adoption, and training activities with international partners;

- Growing capacity to assess the health and economic impacts of regulation, and using this information to inform actions to protect public health;

- Communicating about risks, including the uncertainty around them, especially during a crisis; and

- Communicating the ways regulation improves quality, safety, and access, using different strategies to convey this information to government leaders, regulated industry, and the public.

Every agency has to make different determinations about the risks confronting it; those determinations are based both on data and on an understanding of the will of society. To this end, every agency needs access to information and a strategy to communicate with government leaders, the public, and regulated industry, both to solicit their input and to convey the risks facing the agency.

Identifying and ranking risks depend on data and analytic skills. For this reason, the WHO Global Benchmarking Tool is designed with sub-indicators in each of the nine key functions relating to risk management. Analysis of these indictors can give some insight into an agency’s ability to identify and rank the risks facing it (WHO, n.d.). The WHO and the FAO Food Control System Assessment Tool also emphasizes “capacity to collect and analyze data for risk analysis” (Caipo, 2019). As more countries undergo these assessments, it may be possible to say with more precision how many regulatory agencies can properly use risk to inform decision making.

Furthermore, neither frank communication with the public nor crisis management is easy in places where there is not a certain level of media openness or diversity of sources (OECD, 2016). Nonetheless, effective communication is essential to garnering the support necessary for the regulatory mission. Most regulatory agencies can use cases where serious harm has been averted to their advantage. One famous instance of harm averted is the FDA’s denial of market authorization to thalidomide in the 1960s (FDA, 2018b). There are many examples from low- and middle-income countries as well. For example, in 2017, the Tanzania Food and Drug Authority

began a program of soliciting reports of suspicious products from doctors, pharmacists, and other health workers using smartphones. The successful implementation of this program led to the recall of substandard malaria diagnostic kits (WHO, 2017a).

More mundane regulatory work is also an opportunity for communication. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India’s webpage Success Stories, for example, advertises the agency’s work, including programs to improve the safety of street food (FSSAI, n.d.). Press releases, website announcements, blogs, and smartphone apps are all channels the agency can use to reach the public with messages about the value of newly approved medicines or seasonal food safety warnings. There is also value to publicizing more controversial actions the agency takes to protect public health, such as revocations of licenses or sanctions, before the aggrieved manufacturer does. Using a diversity of tools ensures a wider reach; it also helps the agency stay in control of competing narratives concerning regulatory action.

A good communication strategy considers the type of audience targeted, the tools used to reach them, and clarity of presentation. (Materials intended for health professionals, for example, are written at a different level than those meant for all parents of young children.) A plan to evaluate the effectiveness of the communication materials and areas for improvement should also be articulated early (FDA, n.d.). Such evaluations can measure how aware consumers are of the agency’s work and how far its communications tools reach, especially considering reach in vulnerable communities. These evaluations can guide periodic reshaping of the communication strategy. For example, an evaluation of the FDA’s system for reporting possible adverse events associated with prescription medicines found that posting on early signals may have increased alarm unnecessarily (Chakraborty and Lofstedt, 2012). Regulators may also need to assess this type of sentiment and reshape their strategies in response.

Information on the effects of regulatory action can be especially valuable. Box 5-4 describes how regulatory action can influence diet, for example. If developments at the regulatory agency stand to grow the economy, this too should be publicized. While acknowledging that the price of medicines is influenced by many factors, the agency should be willing to comment on its contribution to economic gains. In El Salvador, for example, revisions to the national medicines law made it easier for quality-approved generics to enter the market, contributing to a 20 to 25 percent reduction in the price of medicines (Yamagiwa, 2015). In Mexico, concerted attention to eliminating the application backlog greatly increased the number of registered generics between 2011 and 2016 and brought down the cost of medicines by about 50 percent on average (Arriola Penalosa et al., 2017).

Finally, in considering the risks facing the regulatory agency, decision makers would do well to remember the importance of organizational culture. A major risk to many agencies is the inability to retain technical staff (IOM, 2012; OECD, 2016). Incentives such as good work–life balance and a career ladder with advancement opportunities can go far to correct this problem, even if government salaries cannot compete with those of the private sector (OECD, 2016).

THE RISKS OF INFORMAL MARKETS1

Data sharing, capacity building, and regulatory cooperation programs all have promise to make regulators work more efficiently, but these tools are all most effective in dealing with the formal, orderly operations of known producers and distributors. In low- and middle-income countries, considerable sale of food and medical products happens outside such channels. These informal markets are often a risk to public health, but steps to mitigating such risk are challenging; regulatory sanctions are, almost by definition, not an effective deterrent to producers who operate outside of the formal market (Jaffee et al., 2019). In such cases, regulators may need to give more attention to strategies to drive consumer preference to the best feasible option and to increase the reach of safe, good-quality options in the market.

Informal Markets for Food

Informal food markets are important in low- and middle-income countries, accounting for about 80 percent of food sold, possibly more in sub-Saharan Africa (Jaffee et al., 2019; Roesel and Grace, 2014). Urbanization contributes to the importance of informal markets, as city dwellers cannot produce their own food. Poor consumers in cities are not likely to have refrigeration, making daily food shopping necessary (Resnick, 2017). The International Livestock Research Institute estimates that poor and middle-class consumers buy almost all their nutritionally dense, animal-source foods in informal markets (Grace, 2015a; ILRI, 2010b). Animal-source foods are important for health; they are also high risk for microbial contamination. Market conditions in informal retail and wholesale are often lacking in refrigeration; safe storage and handling are never assured (Grace, 2015a; Grace et al., 2014; Jaffee et al., 2019; WHO, 2006).

It is often difficult for governments to know how to handle informal food markets. Attempts to arrest and fine informal sellers, destroy their marketplaces, or confiscate their wares are not uncommon, especially in Africa (Resnick, 2017). Such measures can have disastrous consequences for food security and livelihoods; it is not clear that they improve the underlying food safety problems either (Resnick, 2017). Enforcement alone is not likely to have any effect on the underlying market demand for the products informal sellers supply. Softer regulatory tools, such as consumer education, can help nudge consumer preference toward a safer alternative (Baldwin, 2014). Steps to professionalize the management of informal

___________________

1 In this discussion, informal markets refers to “markets which escape effective health and safety regulation” (ILRI, n.d.).

markets can be helpful. For example, informal food markets in Zambia are managed by boards composed of consumers, vendors, and local authorities (Abrahams, 2009; Resnick, 2017). Involving vendors in the management of the markets made them more amenable to paying market fees to improve market sanitation (Abrahams, 2009; Resnick, 2017).

Research across a range of low- and middle-income countries has found consumers to be aware of the risks of microbial contamination in animal-source foods and produce (Alcorn and Ouyang, 2012; Grace, 2015a; ILRI, 2010b; Lapar and Toan, 2010). As a result, the demand for safer foods in domestic markets is predicted to grow over the next 20 years, as the middle class expands and education levels rise (Ortega and Tschirley, 2017). It is not clear what actions would increase consumer demand in such markets, however, or how consumer preferences affect producers (Ortega and Tschirley, 2017). One role for food regulators is to encourage demand for safety and to inform consumers about steps they can take to minimize the risks facing them.

On average, consumers in low- and middle-income countries are willing to pay a modest premium (by some estimates about 5 to 15 percent more) for safe foods (Roesel and Grace, 2014). Education and experience may influence willingness to pay. Research in rural Kenya found that shoppers who understood the danger of aflatoxins were willing to pay a higher premium for maize labeled “clean [of aflatoxin] and tested” (De Groote et al., 2016). This is consistent with research indicating the willingness to pay comes mostly from cities and wealthier shoppers; it increases with rising income, education, and exposure to media (Grace, 2015b; ILRI, 2010a,c; Ortega and Tschirley, 2017). It stands to reason that consumer education mass media are a necessary part of any food safety strategy (Morse et al., 2018). The Safe Food Imperative emphasized the role for consumer engagement, including education toward understanding various food quality indicators (Jaffee et al., 2019).

Evidence on the effectiveness of education to improve safe food practices at the level of farmers and food handlers is less clear (Grace et al., 2019; Jaffee et al., 2019). Although training can improve food safety in the short term, the benefits are not sustainable without continued institutional support (Grace et al., 2019). Since education alone does not necessarily transfer into safer food handling, strategies at the handling and processing levels can include certification or other measures to professionalize food handlers (Jaffee et al., 2019). There is also a role for research to identify methods that are effective for a given country’s markets, bring them to scale, and adapt them to similar contexts. This is an area where the proposed Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science could make useful contributions.

In most low- and middle-income countries, agriculture and food production are characterized by a great many small producers and large,

informal markets complemented by a few very large firms; the structure of the market described sometimes as “elephants and mice” (Grace, 2015a). Given the logistical challenges of reaching all the players in informal food markets, it can be most efficient to introduce controls at aggregating points on the supply chain; the slaughterhouse, the dairy plant, and the wholesale market, for example (Grace et al., 2019). Other risks, such as chemical contamination from pesticides, are better managed at the farm (Jaffee et al., 2019). Working with small farmers on problems such as manure management and safe pesticide use are steps with health and environmental benefits even beyond food safety (Jaffee et al., 2019).

Informal Markets for Medicines

The informal medicines market is also a feature of medicine production and distribution in low- and middle-income countries, though less is known about its size or reach. Research from sub-Saharan Africa suggests that while pharmacies have good reach in cities, they are scarce in rural areas (Wafula et al., 2012). The vendors who operate in their stead are often not qualified for dispensing medicines, and the quality of the stock is uncertain (Wafula et al., 2012). Although the pharmacies in affluent, urban areas stock effective products, they charge accordingly, pricing out poor patients (Wafula et al., 2012). As with the informal food market, informal drug sellers meet a market demand for convenient and accessible sales at a low price (Goodman et al., 2007). And, as with foods, the poorest consumers are the ones most likely to use informal sellers (Bloom et al., 2014).

Regulatory agencies may be more likely to consider aggressive enforcement as a tool to shut down informal vendors in the medicines than food market, as there are not the same concerns about disrupting livelihoods. Closing illegal pharmacies and tightening control over the supply chain have been effective at reducing trade in falsified medicines in Rwanda and Cambodia (El-Jardali et al., 2015; Hamilton et al., 2016). It is not clear that this strategy is as effective in larger countries, however. After a series of raids on informal markets, warehouses, and shipments in the early 2000s, the Nigerian authorities concluded that the regulatory agency alone would not be able to put the informal sellers out of business (Chinwendu, 2008). More recent efforts to promote good distribution practices have promise to reduce the infiltration of falsified products into the supply chain; they also protect against accidental damage to good-quality products through inappropriate storage or handling (Fatokun, 2016; NAFDAC, 2016). Nevertheless, in Nigeria, as in many low- and middle-income countries, the large informal medicines market is a response to a demand for medicines that exceeds supply (NASEM, 2018). It is therefore necessary to increase the supply of affordable, good-quality alternatives.

The demand for medicines is predicted to grow, especially as countries move toward universal coverage (Pisani, 2019). By 2011 estimates, medicines accounted for two-thirds of government spending on health in some countries, a share that is only predicted to increase as the burden of paying for medicines slowly shifts from patients to governments (Lu et al., 2011; Pisani, 2019; Wagner et al., 2014). In the meantime, patients in much of the world will have to make purchasing decisions about medicines in a confusing market where the distinctions between good and bad quality are not clear.

Mobile technology used at the point of purchase can help motivated consumers verify the authenticity of products, usually by checking information on the package or by comparing a mobile photograph to an authentic image (Mackey and Nayyar, 2017). Such technology can be empowering to patients; it can also help engage the public in identifying breaches in the medicines supply chain (Mackey and Nayyar, 2017). For these reasons, the Nigerian regulatory authority is requiring mobile authentication on medicines packaging (PharmaSecure, n.d.); similar measures have been proposed in India (Sinha, 2011). Since the majority of adults in low- and middle-income countries have a mobile phone, these tools could be powerful (Dulli, 2019; Silver et al., 2019).

As in informal food markets, regulators have to use the tools available to them to direct consumers to the good-quality products and to educate society on the risks of shopping outside of regulated channels. Accreditation programs, as described in Box 5-5, hold particular promise for improving the reach of good-quality medical products.

Recommendation 5-2: National regulatory agencies should use evidence to guide strategies to reduce the risk posed by informal markets. Strategies to consider include accreditation or licensing to formalize sellers, consumer education, and increasing competition from regulated products.

In considering regulatory tools to combat informal markets, it is important to note what tools for change are realistically available to the regulatory agency. For instance, national price controls are not within the purview of the regulator, nor is the scope of the national medicines benefit package. A shortage of pharmacists might be remedied by task shifting, the process of delegating some to work to less trained staff, as described in Box 5-5. If professional practice laws disallow such shifts, however, the regulatory agency alone cannot change this. The role of the regulator is to improve access to safe, quality-assured products, but not to formalize the economy. Therefore, this recommendation is mainly concerned with ways

to work with other actors in a decentralized system to encourage consumer behaviors that benefit health and stimulate a competitive market.

There is promise for market mechanisms to improve product safety in the food market, but the process will be slow (Jaffee et al., 2019). In the meantime, regulators have to choose their strategies to improve food safety in a way that promotes food security and rural livelihoods. Success depends a great deal on local context, making it difficult to identify transferable strategies (Grace, 2015a; Jaffee et al., 2019). The recent World Bank publication The Safe Food Imperative emphasized better engagement of consumers, tools to help consumers become “partners in food safety,” and educational materials including education on understanding the various signals of quality in the markets, such as certification programs (Jaffee et al., 2019). Strategies that improve food safety should be inclusive to small farmers, many of whom are women who stand to lose in a rapid modernization of food systems (Grace, 2015a).

Translating food safety knowledge into behavior is often difficult (Zanin et al., 2017). Checklists can be a powerful tool for behavior change; sharing inspection checklists with food vendors, perhaps in simplified form, is one strategy to improve their observance of code (Jaffee et al., 2019). As with the informal medicines market, training and certification of vendors can help (FAO, 2016). Research in Kenya, India, and South Africa has shown that efforts to professionalize street vendors through a combination of training and incentives to be successful in improving food hygiene (FAO, 2016).

Consumer education is another invaluable tool for controlling risks of informal markets. The WHO’s Five Keys to Safer Foods tool has been useful in reaching audiences from food vendors to home cooks and schoolchildren; it is available in 87 languages and has been used in 146 countries (Fontannaz-Aujoulat et al., 2019). Research in Cambodia, Ghana, and Vietnam has found the tool helpful in changing household and vendor behavior, Its success is often attributed to simple, clear messages, and explanations of the reasoning behind the behaviors promoted (Fontannaz-Aujoulat et al., 2019).

Education is a similarly important starting point for controlling informal medicines markets, described in a recent WHO report as, “the first step in preventing the use of substandard and falsified medicines” (WHO, 2017a). Anti-fraud packaging and point of use verification can help identify unsafe products at the point of purchase (Aminu et al., 2017; Hamilton et al., 2016), though these strategies may be most effective among fairly sophisticated consumers. Regulators may use media to direct business away from unlicensed vendors to safer ones, such as the accredited outlets described in Box 5-5. In choosing what strategies to promote, however, it is important to consider the agency’s ability to follow through. Licensing

vendors, for example, is not effective unless supported by inspection and enforcement tools (El-Jardali et al., 2015).

COOPERATION AT VARIOUS LEVELS

Steps taken to mitigate the risks of informal markets can be expected to have a disproportionate return to regulators in low- and middle-income countries because they depend on knowledge of local markets and local risks. Consumer education on safe food storage, for example, will be a successful strategy only if the messages are tailored to local problems and presented in a format accessible and salient to the intended audience. Activities where attention from the regulatory agency improves the safety of products on the market beyond the baseline comparison point should be priorities for regulatory agencies in low- and middle-income countries (Ahonkhai et al., 2016; Roth et al., 2018). The question that remains is how to manage the workload to enable regulators to devote more attention to the so-called value added activities.

Regulatory Reliance

The use of limited resources to add value requires prioritizing those tasks that elucidate risks, tasks such as market surveillance, inspecting distributors, and routine quality testing (Roth et al., 2018). There are also a great many regulatory responsibilities that do not pay off in terms of better understanding of local risks. These jobs are best approached with an eye toward maximizing efficiency and making use of the work of other, trusted organizations (OECD, 2018; Roth et al., 2018). For example, it is often prohibitively expensive to train staff to review new molecules in low- or middle-income countries, or even in many high-income ones. Since FDA or EMA approval is a global signal on the safety and efficacy of a new drug, it may be wise to defer these assessments (Moon et al., 2017). Staff time and funding can then be redirected to market surveillance (sometimes called “phase 4 studies”) that clarify the risks of a drug in the population, adverse reactions, and interactions with other exposures (Cancer Research UK, 2019; HHS, n.d.).

Unilateral acceptance of the FDA or the EMA decisions is an example of regulatory reliance, the process by which an agency “take[s] into account or give[s] significant weight to work performed by another regulator or other trusted institution in reaching its own decision” (WHO, 2018). Reliance agreements allow authorities to make use of shared information, but retain the authority for regulatory decisions (Luigetti et al., 2016). Such reliance, especially in areas where a small agency’s work adds little to no value, should be sought. Reliance agreements can be a boon to any

agency looking to make more efficient use of available resources (Roth et al., 2018). Other benefits include improved scientific rigor, as decisions pull from more expertise and evidence; more opportunities for training and exchange; better clarity to regulated industry, which can encourage a more innovative private sector and a more predictable business environment; and increased networking with other regulatory experts.

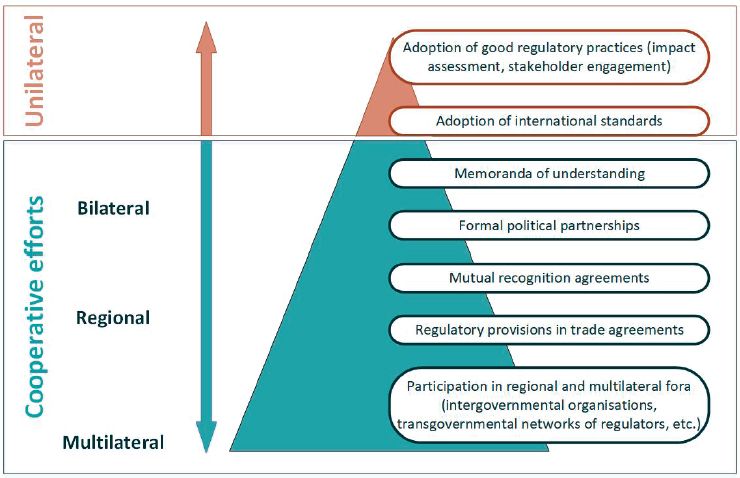

Regulatory cooperation programs often draw on existing economic or political blocs, as in the East African Community and Association of Southeast Asian Nations examples mentioned in the previous chapter. Similarities in language or culture and existing trade relationships make these regional groupings obvious starting points for cooperation, but they need not be the only venue regulators pursue. As Figure 5-1 shows, there are a range of tools available for regulatory cooperation, some of which can be co-opted unilaterally (OECD, 2018; WHO, 2018). Unilateral reliance for some tasks can be a useful strategy while working on the longer-term goal of regional convergence (Roth et al., 2018).

Other Tools for Improving Efficiency

For most agencies, making good use of various tools for regulatory cooperation should be a priority. For some, this means taking advantage of

SOURCES: OECD, 2018, based on OECD, 2013.

the work United Nations (UN) agencies do. The suggested expansion to the WHO prequalification program, recommended in Chapter 3, for example, is only meaningful if procurement agencies make use of the program. Reliance on prequalification saves national authorities time and money on dossier reviews, inspections, and other vetting of suppliers. Nonetheless, prequalified products still must be approved for use by each national regulatory authority, ensuring that registration being sought is for the identical product, dosage form, company, and manufacturer as the one listed with the WHO. The Collaborative Registration Procedure can ease the process of local registration for prequalified products and for products approved by advanced regulatory agencies2 (WHO, 2016a,b). Since its launch in 2013, collaborative registration has expanded to over 30 countries (WHO, 2019). The program is also credited with significantly improving the registration process in participating countries; about half of collaborative registrations take 90 days or less (WHO, 2019).

Such cooperation with the WHO has tangible benefits to public health. When the WHO prequalified a meningococcal conjugate vaccine from Serum Institute of India, for example, it worked with regulatory authorities in Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal to introduce the vaccine, resulting in a roughly 90 percent reduction in risk of meningitis (Ahonkhai et al., 2016; Cooper et al., 2019; Daugla et al., 2014). The FAO and the WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission produces tools for food safety: Codex guidelines and standards are a good starting point for regulators looking to harmonize their national food laws (Halabi and Lin, 2017).

There are also a great many private organizations whose work can ease the task of regulatory cooperation. The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) produces technical guidelines to facilitate medicines registration, including a common format for regulatory review (ICH, n.d.). This format is now widely used, even in countries that are not ICH members, reducing unnecessary work for both government and industry (Garg et al., 2017).

Food regulation is arguably even more of a public–private operation, with certification now embedded into food laws in the United States, Europe, and parts of Asia (Halabi and Lin, 2017). The Euro-Retailer Produce Working Group protocol on good agricultural practices and the Global Food Safety Initiative standards discussed in Chapter 2 are other prominent examples of the so-called co-regulation of food safety, meaning a hybrid regulatory model with shared government and private sector responsibilities (Garcia Martinez et al., 2007). Table 5-1 shows how different types of food standards can be used by government or private-sector stakeholders.

___________________

2 Meaning agencies benchmarked at level four, formerly described as “stringent regulatory agencies.”

TABLE 5-1 Different Types of Public and Private Standards

| Type of Standard | Source of Standard | Authority for Adoption | Implementation | Conformity Assessment | Enforcement | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulations—Public, mandatory standards | Government | Legislation or regulatory agency | Private firms | Government inspector | Criminal or administrative courts | The regulatory authority’s published rules |

| Public voluntary standards—Standards created by public bodies but whose adoption is voluntary | Government | Legislation or regulatory agency Private firms or organizations | Private firms | Auditor, can be government or private | Certification body; can be government or private | The French Ministry of Agriculture’s “Label Rouge” for products meeting stringent quality standards |

| Private standards referenced in regulation—Standards developed by the private sector that governments then reference | Private body—commercial or noncommercial | Legislation or regulatory agency | Private firms | Private or government auditor | Criminal or administrative courts | The U.S. Food Safety Modernization Act references approved third-party certifications |

| Voluntary private standards—Standards developed and adopted by private bodies. Often business-to-business standards | Private body—commercial or noncommercial | Private firms or organizations | Private firms | Private auditor | Private certification body | British Retail Consortium standards |

SOURCES: Adapted from Garcia Martinez et al., 2013; Henson and Humphrey, 2010.

The use of third-party standards for food safety regulation is relatively common, partly because enforcement of food safety laws can be challenging given international supply chains (ACUS, 2012; Garcia Martinez et al., 2007). On one hand, compliance with third-party standards can help producers in low- and middle-income be competitive in more lucrative markets (Henson and Humphrey, 2010). At the same time, such standards are exacting and may block small farmers from market entry, though the evidence supporting such exclusion is mixed (Faour-Klingbeil and Todd, 2018; Henson and Humphrey, 2010).

Voluntary standards can be valuable tools for food suppliers looking to expand market access. Proof of animal welfare or environmental measures, as the Label Rouge certification referenced in Table 5-1 provides, can command a premium in certain market segments (Synalaf, 2013). Such standards should serve as a complement to, not as a substitute for, the core food safety protections regulatory agencies provide.

When viewed as a way to save on enforcement costs and increase the acceptability of regulatory policies, co-regulation can be a useful strategy for food regulators (Garcia Martinez et al., 2013). Because it involves a shift of emphasis from more reactive methods of regulation to prevention, it can also be appealing as a way to triage public resources (Rouvière and Caswell, 2012). Especially in food safety, the preventive approach, and one that makes good use of the wealth of information in internal inspections and process audits, is increasingly favored (Lin, 2014; Rouvière and Caswell, 2012). Perhaps for these reasons, voluntary certification schemes are gaining popularity in low- and middle-income countries (Jaffee et al., 2019). It may be too early to know how well these tools are working, but support from regulators, in the form of consumer education or endorsement of scientific certification schemes for example, could help these tools realize their maximum value (Jaffee et al., 2019). As FAO guidance on voluntary standards explained, the public sector has a responsibility to coordinate these standards so that they stimulate a market for safe foods, rather than serve as a barrier to entry, especially for small producers (UNEP and FAO, 2014).

As with regulatory cooperation, countries can share the infrastructure that supports quality. The Southern Africa Development Community, for example, has a regional accreditation body (SADCAS, n.d.-a). Established by the WTO’s Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement, the program aims to improve laboratory services including testing, calibration, and medical laboratories in the region (Mutasa, 2014; SADCAS, n.d.-b). Accreditation from the regional authority provides an assurance of technical competence that many participating countries would not otherwise have, and it advances longer-term shared goals of protecting health and facilitating trade (Mutasa, 2014; SADCAS, n.d.-b).

The private sector also has an accreditation infrastructure in place that can enrich national training and compliance activities. At the same time, the private sector does not have the same motivators as government, and its prominence in regulation is controversial, seen to increase the already sizable power of large firms in the food market (ACUS, 2012; Garcia Martinez et al., 2007, 2013). For these reasons, co-regulation may work better in places where sophisticated understanding of regulatory goals is common in private firms (Garcia Martinez et al., 2013). To serve the goal of maximizing the value of staff time and resources, regulators should look for ways to make use of other organizations’ work. Without wishing to set up a false equivalence between the resources available through UN agencies and those of the private sector, the committee encourages regulators to consider both as a starting point for establishing standards and monitoring quality.

Recommendation 5-3: National regulatory authorities should take advantage of global tools to support regulatory actions. Resources from United Nations agencies, including World Health Organization prequalification and Codex standards, are examples of such tools, as are the third-party standards increasingly used in food and agriculture.

Given the inevitable shortage of resources and the complicated, international nature of food and medicines production, there is an onus on the regulatory authority to seek the most efficient way to ensure product quality. There is valuable, credible information in third-party certification programs, as there is in the WHO prequalification assessment. Regulators can make use of these tools, as well as the publicly available Codex standards and guidelines in their work. An efficient use of such information can allow agencies in low- and middle-income countries more time and resources to combat risks unique to their contexts.

The committee recognizes that there is room for misuse or misunderstanding in implementing this recommendation. Even the relatively straightforward WHO prequalification program could be misused if regulators understood prequalification of one product as a transferable imprimatur to a manufacturer’s entire product line. Particularly in its application to food safety, the potential for third-party tools to advantage larger businesses should be considered. The Administrative Conference of the United States recommends that, before deciding to use a third-party program to assess compliance, governments assess the capacity of the agency and the relative costs of the program, as well as the extent to which such programs may be unfair to small businesses. It encourages the regulatory agency to oversee third-party programs to ensure that they continue to advance the government’s goals (as opposed to the market expansion goals of large companies) (ACUS, 2012).

Since third-party standards vary widely, it is difficult to comment on their likelihood of helping or harming small- and medium-sized producers in developing countries; research on such effects is mixed (Henson and Humphrey, 2010). The inclusion of experts from low- and middle-income countries on the governing boards and technical committees of standard-setting organizations, since they are in the Codex committees and the private Global GAP, is one strategy thought to promote inclusion (Henson and Humphrey, 2010).

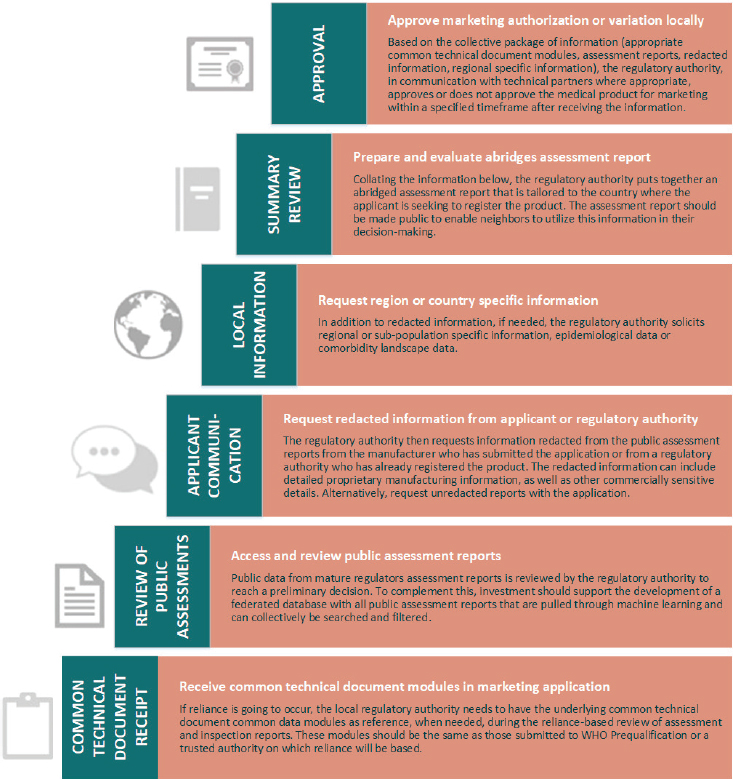

This strategy also has implications for the way regulators approach their work. Most agencies, especially those in low- or middle-income countries, need good generalists, regulators with broad knowledge of the field who can make use of and judge the credibility of a range of technical documents (e.g., inspection reports, public assessments, and international guidelines such as those produced by Codex or the ICH). Small countries in particular rely on critical assessments of information produced abroad (Fefer, 2012). For example, Figure 5-2 shows how reliance might work for medicines registration, referencing the use of publicly available data from other agencies and the ICH Common Technical Document. The breadth of knowledge required makes the work challenging, and also unlike that of regulators in Europe or North America. Training and credentialing programs should reflect this distinction, and might be an area for the proposed Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science to explore.

Efficiency and Delegating

The purpose of collaboration, co-regulation, and work sharing is to increase countries’ efficiency, as well as to reduce restrictions on the movement of food and medicines internationally. Sparing resources allows agencies to attend to key local activities that others cannot perform, such as local inspections and controls on high-risk products sold in informal markets. But realizing the benefits of work sharing requires consideration of the full range of work sharing options, identifying those tasks that are best shared among different national governments and those that can be devolved to lower levels of government. In short, core policy work of the agency cannot be devolved to municipal or provincial authorities, though jobs may be delegated to the national agency that retains ultimate authority.

The risk-based framework described earlier in this report can be used to guide countries in identifying tasks suitable for the national agency, those better delegated to state or local authorities, and those candidates for international sharing. For example, a country may have data that allow the ranking of food safety risks based on disability-adjusted life years, or, as is more likely the case in low- and middle-income countries, it may rely on aggregate regional data on the same risks. New medicines approval may

SOURCE: Roth et al., 2018.

rely on a country’s own review, a joint review with neighboring countries, or the acceptance of a trusted foreign authority’s review.

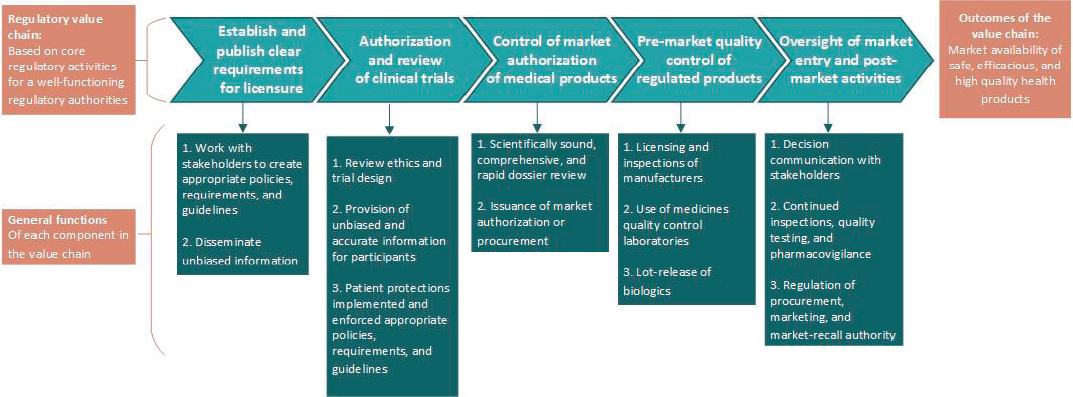

The idea of a regulatory value chain can also be useful in organizing work sharing and delegation (Chahal et al., 2016). Figure 5-3 shows core regulatory activities in the top band; those further to the left are candidates for regional regulatory cooperation or the unilateral acceptance of a trusted authority’s work. Those post-market tasks on the right of the band, including communication with the public, testing, and issuing recalls, are essentially domestic jobs, with some elements of them ripe for delegation to provincial or municipal authorities.

SOURCE: Adapted from Chahal et al., 2016.

Regulatory agencies often work at multiple levels of government (Jaffee et al., 2019; Kaddu et al., 2018). There is no universal blueprint for making the public sector more efficient, but communication among government agencies, both at the level of the national government and at various subnational levels, will always be crucial (Curristine et al., 2007). In terms of managing food and medicines, there are tasks such as the inspection of pharmacies and restaurants that lend themselves to oversight at provincial or municipal levels. When more than one level of government is responsible for advancing larger policy objectives, considerable coordination among those levels becomes important (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009).

A 2009 analysis for the OECD found “duplication of rules, overlapping and low-quality regulations, and uneven enforcement” to be the most common problems when sharing regulatory responsibilities at different levels of government (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009). Capacity is often not as strong at sub-national levels, especially for technical work (Smoke, 2015). Partly because of financial limitations, it is difficult for subnational levels of government to maintain the staff or other resources, such as laboratories (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009).

Research in Malawi found the food inspection services at the district and city levels to be severely understaffed and noted confusion regarding guidelines, standards, and enforcement, problems only complicated by the variety of ministries with food safety responsibilities (e.g., agriculture, tourism, health) (Morse et al., 2018). It may stand to reason that in countries with a more federal system of government, the pathway for delegation would be more clear, but it is not necessarily so. Medicines regulation in India, for example, is shared between the central and state governments (Gupta et al., 2017). The state authorities have sole responsibility for distribution and sale, as well as most of the authority for licensing and inspecting manufacturers (exceptions are made for high-risk products, WHO manufacturing inspections, and certain federal jurisdictions) (Chowdhury et al., 2015). In practice, regulatory implementation varies widely among states (Chowdhury et al., 2015; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2003). In some places, licensing works well, but others have problems (Chowdhury et al., 2015). Managing the uneven quality of the state authorities is a significant challenge for the national agency.

Inspectors may fear for their safety in places were unscrupulous manufacturers have ties to organized crime; the inspectors’ obligation to appear in court can compound the problem and takes time away from inspecting (Chowdhury et al., 2015). Quality testing is also problematic; in some states in India central testing labs lack the equipment for the full range of assays (Chowdhury et al., 2015). In India, as in much of the world, there can be an emphasis on putting the national system in place, forgetting that

a lot of the pieces depend on effective work at sub-national levels (Morse et al., 2018).

Recommendation 5-4: National regulatory authorities should determine which functions are most effectively and efficiently carried out directly by the agency and which can be delegated to state or local authorities; collaboration and data sharing among domestic agencies should be part of any delegation plan.

Analyses of devolution programs in low- and middle-income countries have found that when decentralization happens quickly, there may be confusion over roles and conflict among staff (Cobos Munoz et al., 2017; Nxumalo et al., 2018). Sufficient funding for the increased burden on district and local offices is important, as is taking time to train staff for their new roles (Nxumalo et al., 2018). Fostering good relationships across levels and coordinating policies to avoid overlap or conflicting roles should be a priority in any delegation or devolution plan (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009).

One of the main challenges of cooperating across levels of government is in information sharing. Local offices may have extensive information on small parts of a problem, but this information needs to be shared and managed across levels (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009). Furthermore, the availability of technology at subnational levels of government is less likely in low- and middle-income countries, making even data collection more difficult (Brack and Castillo, 2015). Technological limitations, while challenging, can be an opportunity. Chatham House recommends putting the basic foundation for data literacy in place before implementing a data policy that may be unsuitable to the local context (Brack and Castillo, 2015). Especially in places where data sharing is new, it is also important to articulate a clear and compelling argument for data sharing, framing it in terms of the benefits accrued to society at large and to individual stakeholders (Brack and Castillo, 2015).

Another common obstacle to work sharing is having sufficient funding for all jobs delegated to provincial or municipal authorities (Cobos Munoz et al., 2017). The central government always has an advantage in collecting revenue (Smoke, 2015). When sub-national governments do not have reliable income, transfer from the federal government might be necessary (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009). There are also strategies the national government can take on to pool resources and help subnational levels build economies of scale (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009). The Food Emergency Response Network, for example, gives various state, local, and tribal food safety laboratories protected surge capacity during large-scale outbreaks (FDA, 2018a). During an emergency, the national network coordinator schedules increased testing across various network laboratories, speeding

response time; the program also supports some sites to develop new analytic methods (FDA, 2018a; ICLN, n.d.).

Delegation and work sharing also require capacity building, both in increasing technical capacity, mostly at the lower levels, and in increasing governance capacity—meaning developing the skills and protocols that allow the levels to work together—at all levels (Smoke, 2015). Clarity in the division of work can go far to improving cooperation (Curristine et al., 2007; Smoke, 2015). Programs that build networks and bring regulators from different levels together can also improve governance capacity, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle of cooperation and capacity building (Charbit and Muichalun, 2009).

There is a mutual dependence among levels of government. In delegating or sharing work among those levels it is important to be clear about who answers to whom and that everyone answers to someone (Nxumalo et al., 2018). District and local regulators may feel greater accountability to local authorities, but even in highly decentralized systems, there is usually also some degree of accountability to the central government; balancing the priorities and accountability among these levels can be challenging (Nxumalo et al., 2018). Some evidene suggests that good professional relationships among staff at different levels can build accountability, causing people to feel that they are all on the same team (Nxumalo et al., 2018).

The national regulatory authority has a responsibility to set the subnational offices up for success, taking stock of the risks facing the country and setting priorities accordingly. In India, for example, where medicines manufacturing is the main driver of the market, inspection against good manufacturing practices will take precedence (Chowdhury et al., 2015). The national government may also need to give grants to states to help them upgrade their facilities (Chowdhury et al., 2015).

REFERENCES

Abrahams, C. 2009. Transforming the region: Supermarkets and the local food economy. African Affairs 109(434):115–134.

Access to Medicine Foundation. 2018. Access to medicines index 2018. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Access to Medicine Foundation.

ACUS (Administrative Conference of the United States). 2012. Administrative conference recommendation 2012–7: Agency use of third-party programs to assess regulatory compliance. https://www.acus.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Recommendation%202012-7%20%28Third-Party%20Programs%20to%20Assess%20Regulatory%20Com-pliance%29.pdf (accessed August 29, 2019).

Ahonkhai, V., S. F. Martins, A. Portet, M. Lumpkin, and D. Hartman. 2016. Speeding access to vaccines and medicines in low- and middle-income countries: A case for change and a framework for optimized product market authorization. PLoS One 11(11):e0166515.

Alcorn, T., and Y. Ouyang. 2012. China’s invisible burden of foodborne illness. The Lancet 379(9818):789–790.

Aminu, N., A. Sha’aban, A. Abubakar, and M. S. Gwarzo. 2017. Unveiling the peril of substandard and falsified medicines to public health and safety in Africa: Need for all-out war to end the menace. Medicine Access @ Point of Care 1:maapoc.0000023.

Anderson, R. 2011. Apple juice is still safe, FDA says. Food Safety News. https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2011/11/apple-juice-is-still-safe-fda-insists (accessed August 20, 2019).

Andrews, J. 2012. 2009 Peanut butter outbreak: Three years on, still no resolution for some. Food Safety News.https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2012/04/2009-peanut-butter-outbreak-three-years-on-still-no-resolution-for-some (accessed August 20, 2019).

APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation). 2018. APEC food safety capacity building initiative: Update to the mid-term review. http://fscf-ptin.apec.org/docs/2018/2018_Independent_Review_of_APEC_FSCF_PTIN_Food_Safety_Capacity_Building_Report.pdf (accessed August 20, 2019).

Arriola Penalosa, M. A., R. Cavazos Cepeda, M. Alanis Garza, and M. M. Lumpkin. 2017. Optimized medical product regulation in Mexico: A win-win for public and economic health. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 51(6):744–750.

Babigumira, J. B., A. Stergachis, T. Kanyok, L. Evans, M. Hajjou, P. O. Nkansah, V. Pribluda, J. Louis P. Garrison, and J. I. Nwokike. 2018. A risk-based resource allocation framework for pharmaceutical quality assurance for medicines regulatory authorities in low- and middle-income countries. Rockville, MD: USAID.

Baldwin, R. 2014. From regulation to behaviour change: Giving nudge the third degree. The Modern Law Review 77(6):831–857.

Bezuidenhout, L., and E. Chakauya. 2018. Hidden concerns of sharing research data by low/middle-income country scientists. Global bioethics = Problemi di bioetica 29(1):39–54.

Bloom, G., S. Henson, and D. H. Peters. 2014. Innovation in regulation of rapidly changing health markets. Global Health 10(1):53.

Bloomberg News. 2019. China’s lethal milk scandal reverberates a decade later.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-21/china-s-lethal-milk-scandal-reverberates-a-decade-later (accessed August 20, 2019).

Boin, A., P. ‘t. Hart, E. Stern, and B. Sundelius. 2005. The politics of crisis: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brack, M., and T. Castillo. 2015. Data sharing for public health: Key lessons from other sectors. London, UK: Chatham House, The Royal Institute for International Affairs. https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/data-sharing-public-health-key-lessons-other-sectors (accessed December 8, 2019).

Bresnick, J. 2019. Is healthcare any closer to achieving the promises of big data analytics?https://healthitanalytics.com/news/is-healthcare-any-closer-to-achieving-the-promises-of-big-data-analytics (accessed August 16, 2019).

Browne, D. 2018. Fixing a crisis of confidence in drug compounding. Washington Examiner.https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/fixing-a-crisis-of-confidence-in-drug-compounding (accessed February 13, 2020).

Caipo, M. 2019. FAO/WHO Food Control System Assessment Tool. Paper presented to Committee on Stronger Food and Drug Regulatory Systems Abroad, February 25, San Jose, Costa Rica.

Cancer Research UK. 2019. Phases of clinical trials. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/aboutcancer/find-a-clinical-trial/what-clinical-trials-are/phases-of-clinical-trials#phase4 (accessed August 28, 2019).

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010. Multistate outbreak of human Salmonella enteritidis infections associated with shell eggs (Final update). https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/2010/shell-eggs-12-2-10.html (accessed August 20, 2019).

CDC. 2014. CERC manual. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/manual/index.asp (accessed August 20, 2019).

Chahal, H. S., F. Kashfipour, M. Susko, N. S. Feachem, and C. Boyle. 2016. Establishing a regulatory value chain model: An innovative approach to strengthening medicines regulatory systems in resource-constrained settings. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 39(5):299–305.

Chakraborty, S., and R. Lofstedt. 2012. Transparency initiative by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER): Two qualitative studies of public perceptions. European Journal of Risk Regulation 3(1):57–71.

Chalker, J. C., C. Vialle-Valentin, J. Liana, R. Mbwasi, I. A. Semali, B. Kihiyo, E. Shekalaghe, A. Dillip, S. Kimatta, R. Valimba, M. Embrey, R. Lieber, E. Rutta, K. Johnson, and D. Ross-Degnan. 2015. What roles do accredited drug dispensing outlets in Tanzania play in facilitating access to antimicrobials? Results of a multi-method analysis. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control 4(1):33.

Charbit, C., and M. Muichalun. 2009. Mind the gaps: Managing mutual dependence in relations among levels of government. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance No. 14. Paris, France: OECD.