1

Introduction

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was established more than a century ago in response to growing public concern with quack remedies, unhygienic food production, and the adulteration of food and medicines (FDA, 2018b). Commerce was also a driving force in the agency’s creation; legitimate food and medicine producers found it difficult to comply with myriad conflicting standards promulgated by state authorities (FDA, 2018b). The agency continues to serve the same basic purpose today. A public health agency, the FDA sets a bar for a market of $2.5 trillion every year, accounting for 20 cents of every dollar the U.S. consumer spends (FDA, 2018a).

Over its history, the FDA has changed in response to various threats and crises. The sulfanilamide crisis of 1937 led to the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which authorized premarket approval of drugs for safety (Sharfstein, 2018). The thalidomide scare led to the 1962 amendments that set standards for drug efficacy (Sharfstein, 2018). More recently, adulterated heparin made under unhygienic conditions in China caused hundreds of allergic reactions, some ending in death, in the United States (Pew Health Group, 2011). The crisis, occurring at the same time as well-publicized food safety scandals in China, brought to light liabilities in modern, multinational supply chains (Pew Health Group, 2011). (Some more recent product safety crises not otherwise mentioned in this report are shown in Table 1-1.)

The FDA’s response included a reorganization, creating a deputy commissioner for Global Regulatory Operations and Policy (Alliance for a Stronger FDA, 2012). The agency also opened foreign offices, where the staff could work more closely with partners overseas (GAO, 2010). With

TABLE 1-1 Product Safety Crises Around the World

| Incident | Country | Date of Incident or Publication | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant formula contaminated with melamine sickens almost 300,000 babies | China | 2008 | Xiu and Klein, 2010 |

| More than 200 deaths and 1,000 hospitalizations from contaminated heart medication | Pakistan | 2011 | WHO, 2013 |

| More than 3,800 cases and 54 deaths from Shiga-toxin on sprouts | Germany | 2011 | Frank et al., 2011 |

| Over 750 people in 20 states contract fungal meningitis from contaminated steroid injections, resulting in 64 deaths | United States | 2012 | CDC, 2015 |

| Between 4 and 16 percent of anti-tuberculosis drugs sampled from pharmacies fail quality testing | Angola, Brazil, China, DR Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Kenya, Nigeria, Russia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, and Zambia | 2013 | Bate et al., 2013 |

| Almost a third of emergency contraceptives fail quality testing | Peru | 2014 | Monge et al., 2014 |

| Aflatoxicosis outbreak with 68 cases and 20 deaths | Tanzania | 2016 | Kamala et al., 2018 |

| Between 72,000 and 169,000 child pneumonia deaths a year because of substandard and falsified antibiotics | Low- and middle-income countries | 2017 | Campbell and Theodoratou, 2017 |

| Poor quality antimalarials cause between 8,500 and 19,800 deaths a year a | Sub-Saharan Africa | 2017 | Goodman and Yeung, 2017 |

| 1,060 people sickened and at least 216 killed in listeria outbreak | South Africa | 2017–2018 | Whitworth, 2018 |

| Substandard vaccine for diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus administered to between 215,000 and 615,000 children | China | 2018 | The Lancet, 2018 |

| Cyclosporiasis linked to Fresh Express salad mix sold at McDonald’s restaurants; 511 confirmed cases in 16 states | United States | 2018 | CDC, 2018 |

| Contaminated formula causes 32 cases of salmonella in infants and young children | Belgium, France, and Luxembourg | 2018–2019 | European Center for Disease Prevention and Control and European Food Safety Authority, 2019 |

| About 1,700 confirmed cases of cyclosporiasis in 33 states | United States | 2019 | CDC, 2018 |

a Based on WHO estimates of 435,000 malaria deaths a year, 93 percent in Africa (WHO, 2019).

increasing international involvement comes an increasing workload. FDA staff overseas influence product decisions affecting the U.S. consumer. More broadly, their job includes building capacity in their host countries, working with their counterparts in foreign governments and with industry and academic representatives (GAO, 2010).

The goal of capacity building was at the center of the agency’s commission, in 2011, of a consensus study report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The committee’s report, published in 2012, emphasized trade, work sharing, and training as tools to improve food and medical product safety in the United States and around the world (IOM, 2012). The report gave a strategy, discussed later in this chapter, for the FDA and other global health and development organizations to consider in their work, mostly limited to a 3- to 5-year action plan.

The world has changed since the 2012 release of Ensuring Safe Foods and Medical Products Through Stronger Regulatory Systems Abroad. The FDA has also changed, so has donor assistance for health in low- and middle-income countries. In light of these developments, the FDA asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene a committee to revisit the topic of strengthening food and drug regulatory systems (hereafter, regulatory systems). Box 1-1 shows the task the agency gave the committee. More information about the committee members answering this charge can be found in Appendix A.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO ITS CHARGE

The committee met four times; a delegation of committee members and staff also had a public meeting in San Jose, Costa Rica, the site of an FDA regional office. Agendas for public workshops are shown in Appendix B.1 In closed session, the committee discussed the information presented at the public workshops in January, February, and April 2019. They also reviewed relevant literature as cited in this report. Members of the public submitted articles and written testimony for the committee’s consideration, available upon request from the National Academies’ Public Records Office (paro@nas.edu).

To better understand how emerging technologies can be used at regulatory agencies, the committee put out a call for comments. This call, shown in Appendix C, was published on the study webpage and shared with regulatory systems experts at the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); it was

___________________

1 Please note revisions to the listed agendas. For example, speakers from the FDA and the USAID were not able to attend the first meeting because of the federal government shutdown. The sponsor briefed the committee on its charge via a conference call on February 5, 2019.

also advertised on the National Academies’ social media, with the National Academies’ global health and food and nutrition listservs, and through the committee members’ networks. Responses to the call for information are included in the public access file for this project.

In its deliberations and during the sponsor orientation to the project, the committee clarified the intended audience for this report. The study sponsors at the FDA are a primary audience, as are other U.S. government agencies that work in the field, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), as well as global health organizations such as the WHO and the FAO, and the

development banks. Producers of food and medical products are an audience for this report, both individually and through their trade groups, as are consumer organizations. Regulators in low- and middle-income countries are another audience for this report. More broadly, this document should be of interest to anyone with a stake in global health, development, or international affairs.

Discussions with the study sponsor also helped the committee set its analytic strategy, in recognition of the wide range of technical areas the Statement of Task introduces. Food safety and the safety and quality of medical products are clearly relevant but are dealt with broadly and positioned as they are relevant to trends in global health and development. Matters of governance and management are central to this report; these are topics that are important to regulators but are not necessarily the technical evaluation, compliance, or enforcement matters that command their attention day to day. This report does deal with some questions of special interest to regulators, such as the underpinning of a risk-based system and the challenges of informal markets, communication, and data management. Nevertheless, the balance of the material presented in this report is concerned with common principles related to both food and medicines regulation, and the relationship of the field to global health and development.

To this end, the report is not divided along interests of food, medicines, and other medical products, but is roughly organized against the Statement of Task shown in Box 1-1. This chapter deals with the 2012 report and with the changes affecting regulatory systems in the last 8 years. The next chapter gives an overview of the broader health and development context affecting demand for food and medicines and support for regulatory systems. It also introduces risk-based decision making and other key concepts in modern product safety, along with the main stakeholders and some of the relationships among them. Chapter 3 discusses how regulatory systems could be better incorporated into global health and development programming, highlighting the role of development finance and long-term investment in regulatory agencies, ways to expand the WHO prequalification program, and other strategies to advance regulatory science. Chapter 4 moves to the national level in considering a conducive environment for regulatory systems and the pros and cons of different organizational and financing strategies. Chapter 5 turns to internal matters at regulatory agencies, suggesting ways to improve scientific rigor and make work more manageable.

Core principles of regulation apply to both food and medical products. There are other similarities, such as a diverse set of manufacturers, the value of preventive controls, and the importance of surveillance. Because this report is concerned with regulatory systems and product safety, much of

the discussion applies broadly to both sectors. For those points that apply to just one field, this is noted in the discussion.

This report recognizes the responsibility national regulators have for the products in their markets. At the same time, these agencies do not operate in a vacuum. With this in mind, the report gives considerable emphasis to actions at the global and national level that foster the ability of the regulatory agency to function. The recommendations start at the global level, then move to changes at the country level beyond those in the control of the regulatory agency or agencies. The last group of recommendations suggests actions at the level of regulatory agencies.

Understanding the committee’s task also requires some attention to those topics that are outside the scope of this report. The problem of falsified and substandard medicines is not a primary focus of this report, insomuch as it is one of the challenges facing medicines regulators. Similarly, this report does not contain detailed analysis of trade policy or original data collection. While food safety is a topic of this report, the related topic of agricultural development is only tangentially relevant.

GLOBALIZATION AND REGULATORY SYSTEMS

The FDA Office of International Programs commissioned Ensuring Safe Foods and Medical Products Through Stronger Regulatory Systems Abroad at a time when several high-profile product safety lapses had called into question the extent to which the United States, or any country, could reasonably guarantee the safety of food and medicines produced and distributed through expansive global supply chains. The idea that food or medicines could be poisoned and the source never come to light scared the American public. But at the root of the heparin scandal was a more vexing, if mundane, problem: The agency charged with regulating global supply chains did not have the authority or the resources to work outside of the United States (Senak, 2008).

Food and medical products are produced outside the United States because globalization changed the way companies do business. It changed government too, though perhaps more slowly. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released its first ever global strategy, a document that highlighted how the health of Americans was intertwined with the health of people around the world (HHS, 2012; Sullivan, 2018). Securing supply chains was a main objective of this strategy, which cited risk analysis and strengthening of partnerships with other regulatory agencies as essential means to product safety (HHS, 2012). Across all its goals, the strategy emphasized how improving the health of Americans requires working outside of the United States, and also working outside of what would typically be seen as health, on economic and infrastructure problems

sometimes at the root of disease and early death (Daulaire, 2012; HHS, 2012).

The 2012 Report Recommendations

This position was consistent with the strategy outlined in the 2012 report on regulatory systems. The Statement of Task for the report, shown with its recommendations in Appendix D, asked the committee to identify core elements of regulatory systems and priority areas for FDA engagement, with special consideration given to certain emerging markets. As Appendix D shows the report’s recommendations were divided into domestic and international actions; it also sets out the committee’s assessment of the main gaps in regulatory systems in developing countries, and its summary of the essential elements of regulatory systems. In its advice to the FDA and other U.S. organizations, the committee encouraged the agency to make risk the guiding principle for all the agency’s operations. The committee recognized that the most pressing risks facing the agency may be in foreign producers, and that the FDA’s authorizing legislation might need to be changed if it were to redirect substantial attention abroad (thereby assuring the safety of ingredients and products imported to the United States). Considering the challenges of monitoring products and tracking disease in developing countries, the report also recommended that various U.S. government agencies give more support to surveillance systems in low- and middle-income countries, both post-market surveillance for medicines and foodborne disease surveillance (through the PulseNet program, for example).

As Appendix D shows, several of the 2012 report’s recommendations dealt with securing multinational supply chains. The report also recognized that, while globalization of supply chains had caused some of the problems facing the agency, it also held the promise to solve them (IOM, 2012). For example, the scale of foreign manufacturing exceeds the reach of the FDA’s inspectorate, but the sharing of inspection reports from other advanced regulatory agencies can help close the gap. The committee encouraged the agency to move to paperless systems to improve efficiency and to facilitate work sharing among other advanced regulatory agencies, and recommended sharing of inspection reports as a goal for both governments and industry associations.

Similarly, global trade and telecommunications have made the world more connected. In response, governments of both developed and emerging economies have, since 1999, come together in the G20, an economic forum that aims to promote international financial stability (Ramachandran, 2015). The 2012 report identified the G20 as the ideal venue to promote the importance of strengthening regulatory systems. It also explored ways

the private sector and academia might be better included in the discussion about food and drug safety. In an effort to direct private sector and academic research at developing technologies suitable for use in low- and middle-income countries, the report suggested that the FDA and the USDA implement Cooperative Research and Development Agreements for fraud detection, tracking, and verification technologies. It also suggested ways for regulatory agencies in developing countries to draw on the technical depth in their countries’ private industries and universities.

One of the main messages in the 2012 report concerned the training and retention of quality staff in the regulatory agencies. The committee stressed the value of training for regulators in low- and middle-income countries, as a means both to improve the regulatory process and to build professionalism and morale at agencies. To this end, it recommended that the FDA invest in training for staff at its counterpart agencies overseas (IOM, 2012).

Investing in safe food and good-quality medical products abroad is one of the best examples of development assistance being in the enlightened self-interest of the donor. Around and after the release of the 2012 report on strengthening regulatory systems, more donor and international organizations took an interest in a previously neglected piece of health systems. Without overstating the relationship between the 2012 report and subsequent developments, a brief review of progress in the field is necessary.

Major Changes in the Field

The last 10 years have seen increasing recognition of the interconnectedness of regulatory systems, meaning that regulatory failures in one market can have consequences somewhere else. This recognition, combined with an increased demand for medical products and safe foods (discussed in the next chapter), has spurred interest in strengthening regulatory systems. It is important to note that this interest has been a gradual evolution. Even when considering progress since the previous report, an observer might raise the valid observation that the root problems are largely the same today as they were in 2012. Factors such as weak institutions or limited technical capacity are, though improving, still relevant underlying conditions.

Key programs may have discrete start times, but they are representative of a broader change happening slowly. Nevertheless, some orientation to important changes since 2012 is necessary to understand the field today. Given its role as the global standard setting body in health, and its work with governments around the world on health and health systems, the WHO has had a role in many of these efforts (WHO, n.d.-c).

Efforts to Build Medical Products Systems

One of the most prominent examples of the WHO’s involvement in regulatory systems is in action against falsified and substandard medicines. In 2012, WHO member states passed a resolution against falsified and substandard medicines2 (WHO, 2017a, n.d.-b). The immediate work plan under this mechanism included strengthening national regulatory authorities and quality control labs, and collaborating on surveillance and monitoring of the drug supply (WHO, 2012). To this end, the WHO launched a global surveillance and monitoring system for unsafe medicines in 2013 (WHO, 2017c, n.d.-a). Part of the system includes training regulators, including inspectors, quality control technicians, and experts in surveillance and enforcement (WHO, n.d.-a). Reporting suspect medicines to central authorities in Geneva via electronic rapid alert is also an important part of the process (WHO, n.d.-a). Regulators can then check their reports against a secure international database of compromised products and work with WHO staff to determine if the same problem is showing up in multiple markets (WHO, n.d.-a).

Global coordination on falsified and substandard medicines has exponentially grown the muscle of regulatory agencies in low- and middle-income countries. Through central reporting, places that once had little to no capacity to monitor markets now have information from around the world at their fingertips, making it easier to identify global patterns. Almost 1,500 falsified or substandard products were reported to the WHO between 2013 and 2017 (WHO, 2017c). The first report from the Global Surveillance and Monitoring team acknowledged that finding problems depends more than anything on active market surveillance, as well as on staff at the national regulatory authority reporting the problems to the central WHO team. Even so, their data suggest that inexpensive, lifesaving medicines—anti-malarials, antibiotics, and painkillers (including anesthetics)—are commonly compromised (WHO, 2017b).

Earlier research on the problem of falsified and substandard medicines commented on the irony of the problem: that the very data that would compel greater attention to medicines regulatory systems are unavailable when the systems do not work (Buckley et al., 2013; IOM, 2013). The WHO programing on falsified and substandard medicines has improved the situation. With more attention directed to identifying poor quality medicines in the market, donors and governments have better reason to invest in fighting them. Two years after the World Health Assembly’s first resolution against falsified and substandard medicines, it passed another resolution on

___________________

2 The resolution referred to “substandard, spurious, falsely-labelled, falsified, counterfeit” medicines, a descriptor used at the time, and since rejected in favor of the clearer “falsified and substandard.”

strengthening regulatory systems, urging member states to invest in their regulatory systems, to pool resources for essential jobs when necessary, and to take stock of the strengths and weaknesses in their systems so to create useful institutional development plans (WHO, 2014). The resolution also affirmed support for the WHO to evaluate the performance of regulatory systems, something discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 (WHO, 2014).

Whether the 2014 WHO resolution, with its emphasis on pooling resources, was the cause or an effect of greater interest in regulatory cooperation internationally cannot be said, but international harmonization of regulatory requirements has improved considerably in the last 5 years. For example, the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), a group that brings together medicines regulators, industry associations, and other stakeholders to facilitate harmonization, has grown considerably in the last 5 years. At its founding in 1990, the ICH included the regulatory authorities of the European Commission, Japan, and the United States, and three associations representing innovator pharmaceutical companies (ICH, n.d.-a). Ten years later, ICH members included those countries that conduct new molecule review, representing about 15 percent of the world’s population (WHO, 2002). Today, in addition to the three founding members, ICH members and observers include over 20 countries and 6 regional harmonization groups, as well as an expanding list of industry associations and other organizations involved in regulatory policy or procurement, or otherwise affected by regulatory harmonization (ICH, 2018). New observers in the ICH include the East African Community, the Southern African Development Community, and the Pan American Network of Drug Regulatory Authorities (ICH, 2018). The changing, more global composition of the ICH allows medicines regulators in small or low-income countries to have a say in the harmonization process, including the consensus building process for new guidelines, and to build valuable relationships with their counterparts in foreign agencies (ICH, n.d.-b).

Harmonization for medical device regulation has a shorter history; the medical device group analogous to the ICH, the International Medical Device Regulators Forum, was founded in 2011 to promote regulatory convergence for devices (IMDRF, n.d.-b). The forum involves regulatory authorities from nine countries and the European Union, as well the WHO and several regional affiliates (IMDRF, n.d.-a). In an effort to reduce the regulatory burden on both device manufactures and industry, members developed a single audit system that would meet requirements of all participating regulators (FDA, 2019b). The FDA and other regulatory agencies, including those of China, Brazil, and Russia, now accept these audit reports, allowing them to perform far fewer inspections (FDA, 2019b).

Other venues for regulatory collaboration stem directly from the WHO’s interest in the topic. Since 2012, the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities has brought together the heads of agencies for strategic discussions about common problems (ICMRA, 2017a,c). Twenty-four regulatory agencies are members; the shared priorities identified at coalition meetings give some insight into the challenges facing them, including crisis management, pharmacovigilance, and supply chain integrity (ICMRA, 2017b).

Efforts to Build Food Safety Systems

Food safety is also the subject of growing international interest. In 2015, the WHO released the results of an 8-year investigation on the global burden of foodborne disease (WHO, 2015a). While acknowledging serious limitations in the data, mostly because of problems with surveillance and laboratory capacity, the report estimated 600 million cases of foodborne illness in 2010, causing over 400,000 deaths (WHO, 2015a). Children under 5, though accounting for only about 9 percent of the world’s population, accounted for almost a third of these deaths, or 125,000 a year (WHO, 2015a,b).

It is hard to overstate the importance of the WHO report and the work of the Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group. It has been long accepted that foodborne disease is underreported, and even when it is reported, the source of the infection is often difficult to pinpoint (Bettencourt, 2010). The WHO report, for the first time, put numeric parameters on the scope of the problem. As the report explained, foodborne disease, which is most common in the world’s poorest countries, can impair people’s ability to work, thereby aggravating the cycle of poverty (WHO, 2015a). When magnified over the population, this pattern holds back economic development and also damages local industries dependent on safe food, such as tourism (WHO, 2015a). Agriculture, a field that employs almost 60 percent of the work force in the least developed countries, and about a third in all low- and middle-income ones, stands to be particularly hurt (World Bank, 2019).

At the same time, there are limitations to the WHO report that influence countries’ ability to respond to it. Despite citing goals of improving assessment and response to foodborne illness at the national level, results from the study were published in regional aggregates, partly because of methodological limitations in the way the data were derived (Havelaar, 2016; Havelaar et al., 2015; WHO, 2015a). This means that no country can reference its results to monitor its performance over time or relative to other countries, and no regulatory agency can use the results to advocate for increased investment in food safety.

Another challenge in controlling foodborne outbreaks has always been identifying the contaminated food and knowing when the pathogen entered the supply chain. A powerful tool to answer these questions came on the market in the late 2000s, when the cost and time needed for genome sequencing fell dramatically (Stevens et al., 2017). By sequencing the genomes of pathogens drawn from a restaurant, processing plant, or farm and comparing patient samples, it is possible to identify the source of an outbreak quickly, making it easier to remove the source from the food supply before more people get sick. Such is the idea behind GenomeTrakr, a program the FDA started in 2012 (Timme et al., 2018). The program brings together different food safety laboratories, including those at the FDA field offices, state and local health departments, and universities, to sequence the genomes of pathogens from patients and environmental sources (restaurants, farms, etc.) (Timme et al., 2018). The laboratories then report the sequences to a public database. Labs around the world can participate in GenomeTrakr, allowing for international outbreak investigation and identification of relationships between geographically disparate samples, something necessary in a global food supply chain (FDA, 2019a).

But the promise of whole genome technology remains out of reach for many countries. All of the 20 GenomeTrakr labs outside the United States are in high-income countries. The laboratory analysis necessary to support genome sequencing is often unavailable in developing countries, where more routine testing for chemical and biological hazards is challenging (Vipham et al., 2018). Other equipment and consumables needed to run a modern food laboratory can be prohibitively expensive or hard to find, and their use depends on human capacity for laboratory analysis, another major limitation (FAO, n.d.; Vipham et al., 2018).

Building capacity for food safety is a focus of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FDA, 2013). Passed in 2011, this law shifted the FDA’s emphasis from reaction to prevention so, as then deputy commissioner for Foods Michael Taylor described it, “prudent preventive measures will be systematically built into all parts of the food system” (Taylor, 2011). For example, under the act, food companies are required to identify the points in processing when contamination is most likely, and put preventive measures in place at those steps (Olson, 2011). This emphasis on prevention is part of a global trend in food regulation, moving away from a “strict policing function of government,” and involving greater partnership with the private sector (Jaffee et al., 2019).

Globalization of the food supply was a key impetus for the Food Safety Modernization Act, which put requirements on food importers to guarantee that foreign producers they work with meet the requirements for the U.S. market (Olson, 2011). To this end, it formalized recognition of third-party

accreditation, allowing producers with certain recognized certifications3 improved access to U.S. markets (FDA, 2018c). It also mandated more frequent inspections of producers abroad. Increasing inspections puts greater demand on the FDA, although the budget necessary to support such inspections has not been forthcoming (Olson, 2011). The agency’s Food Safety Dashboard posts information about the private sector’s compliance with the new requirements (FDA, n.d.).

Work Sharing and Capacity Building

The increase in inspections required of the FDA is a function of the increased complexity of modern manufacturing systems. In an effort to adapt to these changes and simultaneously improve efficiency, the agency has recently entered into agreements to allow the agency to recognize the procedures, especially the inspections, of European authorities (FDA, 2017a). Mutual recognition agreements allow the United States and its counterpart European agencies to avoid duplicating work and to spend their inspection resources more efficiently (FDA, 2018d). The mutual recognition agreements currently in force with the FDA pertain to inspections of medicine and biologics producers, as well as organizations conducting clinical trials (EMA, n.d.). A recent National Academies committee concluded that, given the complex, global nature of modern drug supply chains, work sharing with other regulatory authorities is an essential part of modern good regulatory practice (NASEM, 2020).

The movement to greater collaboration among regulatory agencies allows the participating agencies to work more efficiently. By reducing duplication, it also eases the regulatory burden on industry. By making market entry fairer and more predictable for all firms, it facilitates trade. But maximizing the return on regulatory collaboration depends on the agency’s ability to employ and retain competent staff, a problem discussed at length in the 2012 report (IOM, 2012).

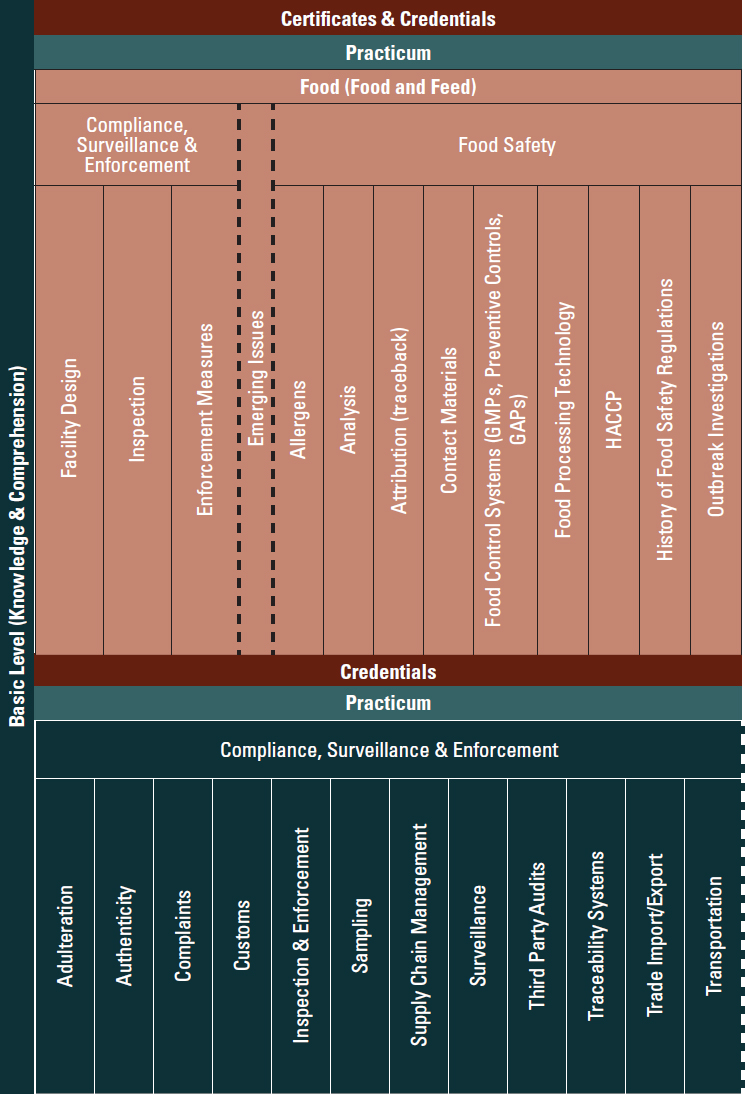

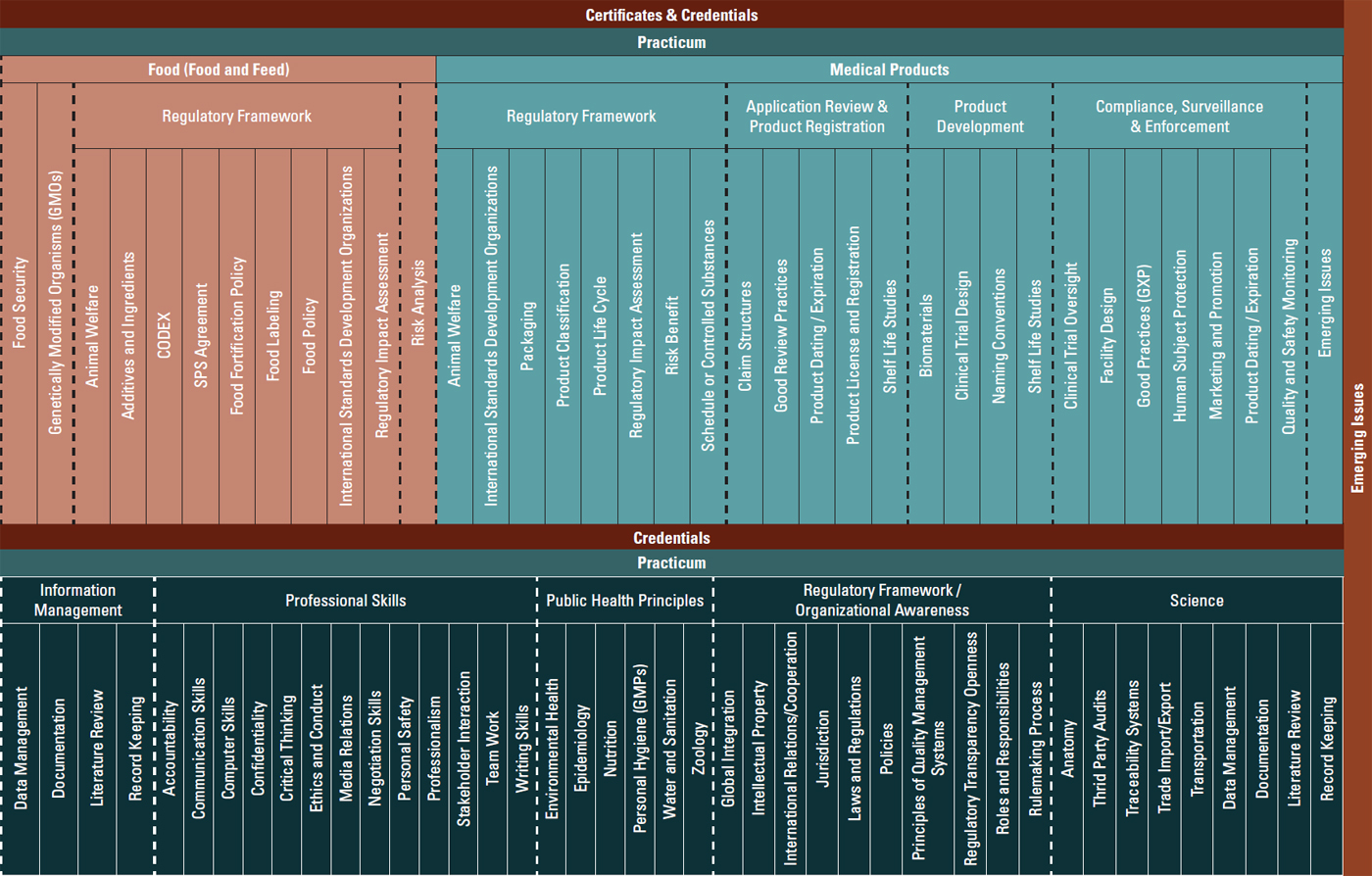

As part of the implementation of the aforementioned report, the FDA worked with the International Food Protection Training Institute, the Regulatory Affairs Professional Society, and the WHO to articulate the necessary skills for government regulatory jobs in low- and middle-income countries (PAHO, 2016; Preston et al., 2013). Figure 1-1 shows the framework developed, highlighting the basic skills regulators need to work well, skills that align with ongoing WHO benchmarking reviews discussed at length in Chapter 3 (PAHO, 2016).

___________________

3 To date, the American National Standards Institute, the American National Standards Institute–ASQ National Accreditation Board, and International Accreditation Services, Inc., are the only recognized accreditation bodies (FDA, 2019a).

The Need for More Progress

The last 5 years have been a time of advancement for regulatory systems, characterized by growing technical capacity, especially in middle-income countries, and increased global cooperation on problems such as falsified and substandard medicines and foodborne disease control. Some of the leadership has come from obvious stakeholders such as the FDA, the European Union regulatory authorities, and the ICH. It is encouraging to note that a broader cross-section of organizations is taking an interest in the topic; the WHO, the FAO, development banks, and bilateral donors are investing in regulatory systems, as are international donors such as Gavi4 and Global Fund.5 Such progress is encouraging for anyone in global health or health systems.

At the same time, there is still considerable work to be done. In Africa, for example, all but one country has a medicines regulatory agency, though only seven of these agencies have the legal mandate for essential regulatory functions (Ndomondo-Sigonda et al., 2017; WHO, 2010). This means that even some basic medicines regulatory jobs such as market authorization, inspection, and quality control are neglected in a part of the world with serious health needs and demand for medical products. The situation is no better in many larger countries. In India, which produces 20 percent of the world’s generic medicines, core responsibilities are shared among several federal and state-level agencies, so standards for even basic functions such as licensing can vary widely (Gupta et al., 2017). Medicines registration, perhaps the most basic responsibility of the regulatory agency, is also a problem in China; at its peak in 2015 the registration backlog was about 22,000 applications (Xu et al., 2018).

The state of food regulatory systems is often much less clear. This is partly because evaluations of the sort cited in the previous paragraph, taking stock of the food safety systems across countries, do not exist for most developing countries, and evaluations that have been done are not often publicly available (Jaffee et al., 2019). The evidence suggests, however, that the cost of unsafe food to the domestic economy in low- and middle-income countries is 15 to 20 times higher than the estimated costs of forgone trade (Jaffee et al., 2019). Furthermore, as the recent World Bank report explained, the gaps between a population’s needs and the existing food safety infrastructure tend to depend most on the country’s development level, with the greatest need in lower-middle-income countries, particularly the large ones (Jaffee et al., 2019). Across developing countries, it is especially difficult to design food safety systems that reach the poorest people.

___________________

4 Officially, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

5 Officially, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

This page intentionally left blank.

Subsistence farmers have little choice regarding their water source, animal bedding, or crop inputs; traditional markets are, almost by definition, not operating to modern hygiene standards. An increased emphasis on meeting international standards in certain market segments can also do unintended harm to the most vulnerable, when food that fails to meet standards for export or chain-market retail is then redirected to places the poorest people shop (Jaffee et al., 2019).

Keeping Pace with Innovative Technology

It is not surprising that countries with fewer resources and weaker institutions have problems with regulatory systems. Even the most advanced agencies are facing the limits of what they can reasonably accomplish. Part of the challenge is that new technologies strain regulatory systems that were designed for conceptually simpler products (Califf et al., 2019). The regulatory approvals process for biosimilars, the generic equivalents of large-molecule, biologically active medicines, is one example of this challenge. Complex biologic medicines, used increasingly since the early 2000s, work in the immune system in novel ways, complicating comparisons between the innovator and biosimilar products (Falit et al., 2015). The regulatory review process for small-molecule generics is therefore not entirely transferable to biosimilars, but an unnecessarily onerous process creates a barrier to market entry, thereby limiting access, driving up costs, and encouraging confusion among prescribers (Falit et al., 2015). The health of many people, and millions of dollars, depend on getting the regulatory framework right.

The computer algorithms used to support health also present regulatory challenges. Mobile apps, for example, might claim to diagnose melanomas at an early stage; internet genetic counseling might offer genome interpretation for a fee. Such technology has vast potential to improve health, and an equally vast potential for quackery (JASON, 2017). It is not yet clear what revisions to the regulatory review process for such technologies might best protect public health without impeding scientific progress. Even if staff time were not a rate-limiting step in the review process, artificial intelligence has forced regulators to confront the Collingridge dilemma: the problem of understanding how to make policies that govern technology when the technology is still developing (Genus and Stirling, 2018). By acting too soon, regulators risk taking actions that hold back science, in this case by forcing artificial intelligence into an unsuitable review process but, by waiting too long, they miss the window to act, let snake oil salesmen prosper, or both.

Gene therapy is another field unfolding faster than the policy to regulate it. Gene editing technology, and the gene drivers that can spread a trait in wild populations, have great potential in health and agriculture and could be used to eliminate dengue or malaria from mosquitoes, for example

(Dooley, 2018). It can be difficult to balance this potential against ecological concerns, especially given uncertainty about how modified genes might spread in the wild (Dooley, 2018).

Other technologies challenge quality assurance systems. In the last few years, regulators in the United States and Europe have grappled with enforcement of good manufacturing practices when devices are made on 3D printers, and with ensuring the safety of robotic devices in a way that controls the risk to patients and still encourages creativity on the part of industry (Califf et al., 2019; FDA, 2017b; Leenes et al., 2017).

All these questions require new and different kinds of skills among regulators (Slikker et al., 2018). And, as the 2012 report made clear, recruiting and retaining staff who understand novel technology to the regulatory agency is difficult; government cannot offer the same salaries as the private sector, and prospective employees may fear losing skills by taking work that removes them, even briefly, from the technological frontlines (IOM, 2012).

As the regulatory agencies in developed countries confront the limits of their processes, it is timely to consider ways these systems might be adapted to today’s markets. In places where the regulatory infrastructure is new or, in the case of medical devices, sometimes nonexistent, there is an opportunity to design a system with the benefit of hindsight. One option is to change laws to allow recognition of foreign review or registration, or to allow for work sharing with neighboring countries. Changing legislation may be a slow process, however, and politicians may balk at any ceding of sovereignty, real or perceived. When the process is designed with an emphasis on efficiency, that calculation can change.

This report sets out a cross-cutting strategy to support good-quality, wholesome food, and quality, safe, effective medical products around the world. The goal of this report is to build on the momentum for strengthening regulatory systems developing over the last 10 years and to set a course for continued progress.

REFERENCES

Alliance for a Stronger FDA. 2012. The FDA as a global actor: A summary report. https://strengthenfda.org/2012/10/02/the-fda-as-a-global-actor-a-summary-report (accessed April 29, 2019).

Bate, R., P. Jensen, K. Hess, L. Mooney, and J. Milligan. 2013. Substandard and falsified anti-tuberculosis drugs: A preliminary field analysis. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 17(3):308–311.

Bettencourt, L. A. 2010. A complex mystery: Finding the sources of foodborne disease outbreaks. https://www.foodsafety.gov/blog/complexmystery.html (accessed May 9, 2019).

Buckley, G., J. Riviere, and L. O. Gostin. 2013. What to do about unsafe medicines? BMJ 347:f5064.

Califf, R. M., M. Hamburg, J. E. Henney, D. A. Kessler, M. McClellan, A. C. von Eschenbach, and F. Young. 2019. Seven former FDA commissioners: The FDA should be an independent federal agency. Health Affairs 38(1):84–86.

Campbell, H., and E. Theodoratou. 2017. Childhood pneumonia. In A study on the public health and socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. Multistate outbreak of fungal meningitis and other infections. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis.html (accessed November 11, 2019).

CDC. 2018. Multistate outbreak of cyclosporiasis linked to Fresh Express salad mix sold at McDonald’s restaurants—United States, 2018: Final update. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2018/b-071318/index.html (accessed October 3, 2019).

Daulaire, N. 2012. The global health strategy of the Department of Health and Human Services: Building on the lessons of PEPFAR. Health Affairs (Millwood) 31(7):1573–1577.

Dooley, C. 2018. Regulatory silos: Assessing the United States’ regulation of biotechnology in the age of gene drives. Georgetown International Environmental Law Review 30:547–568.

EMA (European Medicines Agency). n.d. United States. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/international-activities/bilateral-interactions-non-eu-regulators/united-states (accessed May 3, 2019).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and European Food Safety Authority. 2019. Multi-country outbreak of Salmonella Poona infections linked to consumption of infant formula. Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Falit, B. P., S. C. Singh, and T. A. Brennan. 2015. Biosimilar competition in the United States: Statutory incentives, payers, and pharmacy benefit managers. Health Affairs (Millwood) 34(2):294–301.

FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations). n.d. Strengthening laboratory services. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/agns/pdf/factsheets/StrengtheningLaboratoryServices.pdf (accessed October 4, 2019).

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2013. FDA’s international food safety capacity-building plan: Food Safety Modernization Act 305. Washington, DC: HHS, FDA.

FDA. 2017a. Frequently asked questions/The mutual recognition agreement. https://www.fda.gov/media/103391/download (accessed May 3, 2019).

FDA. 2017b. Technical considerations for additive manufactured medical devices. https://www.fda.gov/media/97633/download (accessed May 9, 2019).

FDA. 2018a. Fact sheet: FDA at a glance. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-basics/fact-sheet-fda-glance (accessed April 29, 2019).

FDA. 2018b. FDA’s evolving regulatory powers. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/history-fdas-internal-organization/fdas-evolving-regulatory-powers (accessed April 29, 2019).

FDA. 2018c. FSMA final rule on accredited third-party certification. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-final-rule-accredited-third-party-certification (accessed Septmeber 9, 2019).

FDA. 2018d. Mutual recognition agreement (MRA). https://www.fda.gov/international-programs/international-arrangements/mutual-recognition-agreement-mra (accessed May 3, 2019).

FDA. 2019a. Accredited third-party certification program: Public registry of accredited third-party certification bodies. https://www.fda.gov/food/importing-food-products-united-states/accredited-third-party-certification-program-public-registry-accredited-third-party-certification (accessed October 3, 2019).

FDA. 2019b. GenomeTrakr fast facts. https://www.fda.gov/food/whole-genome-sequencing-wgs-program/genometrakr-fast-facts (accessed May 3, 2019).

FDA. n.d. FDA data dashboard. https://datadashboard.fda.gov/ora/index.htm (accessed October 3, 2019).

Frank, C., D. Werber, J. P. Cramer, M. Askar, M. Faber, M. an der Heiden, H. Bernard, A. Fruth, R. Prager, A. Spode, M. Wadl, A. Zoufaly, S. Jordan, M. J. Kemper, P. Follin, L. Müller, L. A. King, B. Rosner, U. Buchholz, K. Stark, and G. Krause. 2011. Epidemic profile of shiga-toxin–producing Escherichia coli o104:H4 outbreak in Germany. New England Journal of Medicine 365(19):1771–1780.

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2010. Food and Drug Administration: Overseas offices have taken steps to help ensure import safety, but more long-term planning is needed. GAO 10-960: Report to the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives September 2010.

Genus, A., and A. Stirling. 2018. Collingridge and the dilemma of control: Towards responsible and accountable innovation. Research Policy 47(1):61–69.

Goodman, S., and S. Yeung. 2017. Malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. In A study on the public health and socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Gupta, M., M. Shridhar, G. N. Singh, and A. Khadem. 2017. Regulatory systems in India: An important global hub for medical products and technologies. WHO Drug Information 31(3).

Havelaar, A. 2016. The global burden of foodborne disease: Overview and implications. https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2018-11/Prof%20Havelaar.pdf (accessed December 10, 2019).

Havelaar, A., M. D. Kirk, P. R. Torgerson, H. J. Gibb, T. Hald, R. J. Lake, et al. 2015. World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Medicine 12(12):e1001923.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2012. The global strategy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/hhs-global-strategy.pdf (accessed April 29, 2019).

ICH (International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use). 2018. Current members and observers. https://www.ich.org/about/members-observers.html (accessed April 29, 2019).

ICH. n.d.-a. History. https://www.ich.org/about/history.html (accessed April 29, 2019).

ICH. n.d.-b. Value of membership. https://www.ich.org/about/value-of-membership.html (accessed April 29, 2019).

ICMRA (International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities). 2017a. History of ICMRA. http://icmra.info/drupal/history (accessed May 3, 2019).

ICMRA. 2017b. ICMRA membership country/region and regulatory authority’s website. http://www.icmra.info/drupal/participatingRegulatoryAuthorities (accessed April 29, 2019).

ICMRA. 2017c. International coalition of medicines regulatory authorities (ICMRA). http://www.icmra.info/drupal/en (accessed April 29, 2019).

IFPTI (International Food Protection Training Institute). 2015. Global food and medical product framework. http://ifpti.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/FINAL-GLOBAL-CURRICULUM-FRAMEWORK.pdf (accessed May 9, 2019).

IMDRF (International Medical Device Regulators Forum). n.d.-a. About IMDRFhttp://www.imdrf.org/about/about.asp (accessed May 3, 2019).

IMDRF. n.d.-b. International Medical Device Regulators Forum. http://www.imdrf.org (accessed April 29, 2019).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Ensuring safe foods and medical products through stronger regulatory systems abroad. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Countering the problem of falsified and substandard drugs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jaffee, S., S. Henson, L. Unnevehr, D. Grace, and E. Cassou. 2019. The safe food imperative: Accelerating progress in low- and middle-income countries. Agriculture and food series. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

JASON. 2017. Artificial intelligence for health and health care. McClean, VA: The MITRE Corporation.

Kamala, A., C. Shirima, B. Jani, M. Bakari, H. Sillo, N. Rusibamayila, S. De Saeger, M. Kimanya, Y. Y. Gong, and A. Simba. 2018. Outbreak of an acute aflatoxicosis in Tanzania during 2016. World Mycotoxin Journal 11(3):311–320.

Leenes, R., E. Palmerini, B.-J. Koops, A. Bertolini, P. Salvini, and F. Lucivero. 2017. Regulatory challenges of robotics: Some guidelines for addressing legal and ethical issues. Law, Innovation and Technology 1–44.

Monge, M. E., P. Dwivedi, M. Zhou, M. Payne, C. Harris, B. House, Y. Juggins, P. Cizmarik, P. N. Newton, F. M. Fernandez, and D. Jenkins. 2014. A tiered analytical approach for investigating poor-quality emergency contraceptives. PLoS One 9(4):e95353.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2020. Regulating medicines in a globalized world: The need for increased reliance among regulators. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ndomondo-Sigonda, M., J. Miot, S. Naidoo, A. Dodoo, and E. Kaale. 2017. Medicines regulation in Africa: Current state and opportunities. Society of Pharmaceutical Medicine 31(6):383–397.

Olson, E. D. 2011. Protecting food safety: More needs to be done to keep pace with scientific advances and the changing food supply. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(5):915–923.

PAHO (Pan American Health Organization). 2016. Global regulatory curriculum—A joint effort. Paper read at VIII Conference of the Pan American Network on Drugs Regulatory Harmonization, October 19–21, 2016, Mexico City.

Pew Health Group. 2011. After heparin: Protecting consumers from the risks of substandard and counterfeit drugs. Washington, DC: Pew Health Group.

Preston, C., S. Azatyan, T. Bell, K. Bond, J. Bradsher, M. Brumfield, G. Buckley, T. Hughes, S. Kane, S. Keramidas, M. Miller, M. Morrison, L. Rago, J. Riviere, M. L. Valdez, and G. Wojtala. 2013. Developing a global curriculum for regulators. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

Ramachandran, J. 2015. G20 finance ministers committed to sustainable development. http://www.ipsnews.net/2015/09/g20-finance-ministers-committed-to-sustainable-development (accessed May 9, 2019).

Senak, M. 2008. Heparin at the center of the storm. American Health & Drug Benefits 1(6):23–24.

Sharfstein, J. M. 2018. The public health crisis survival guide: Leadership and management in trying times. New York: Oxford University Press.

Slikker, W., Jr., T. A. de Souza Lima, D. Archella, J. B. J. de Silva, T. Barton-Maclaren, L. Bo, D. Buvinich, Q. Chaudhry, P. Chuan, H. Deluyker, G. Domselaar, M. Freitas, B. Hardy, H. G. Eichler, M. Hugas, K. Lee, C. D. Liao, L. H. Loo, H. Okuda, O. E. Orisakwe, A. Patri, C. Sactitono, L. Shi, P. Silva, F. Sistare, S. Thakkar, W. Tong, M. L. Valdez, M. Whelan, and A. Zhao-Wong. 2018. Emerging technologies for food and drug safety. Regulatory Toxicology Pharmacology 98:115–128.

Stevens, E. L., R. Timme, E. W. Brown, M. W. Allard, E. Strain, K. Bunning, and S. Musser. 2017. The public health impact of a publically available, environmental database of microbial genomes. Frontiers in Microbiology 8:808.

Sullivan, T. 2018. HHS global health strategy 2012. https://www.policymed.com/2012/03/hhs-global-health-strategy-2012.html (accessed May 9, 2019).

Taylor, M. R. 2011. Will the Food Safety Modernization Act help prevent outbreaks of foodborne illness? New England Journal of Medicine 365(9):e18.

The Lancet. 2018. Vaccine scandal and confidence crisis in China. The Lancet 392(10145):360.

Timme, R. E., H. Rand, M. Sanchez Leon, M. Hoffmann, E. Strain, M. Allard, D. Roberson, and J. D. Baugher. 2018. GenomeTrakr proficiency testing for foodborne pathogen surveillance: An exercise from 2015. Microbial Genomics 4(7):e000185.

Vipham, J. L., B. D. Chaves, and V. Trinetta. 2018. Mind the gaps: How can food safety gaps be addressed in developing nations? Animal Frontiers 8(4):16–25.

Whitworth, J. 2018. Experts say consumers must demand improved food safety in Africa.https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2018/09/experts-say-consumers-must-demand-improved-food-safety-in-africa (accessed July 25, 2019).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2002. The impact of implementation of ICH guidelines in non-ICH countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2010. Assessment of medicines regulatory systems in Sub-Saharan African countries: An overview of findings from 26 assessment reports. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2012. WHA65.19 Substandard/spurious/falsely-labelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products. https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/mechanism/WHA65.19_English.pdf (accessed April 29, 2019).

WHO. 2013. Deadly medicines contamination in Pakistan. https://www.who.int/features/2013/pakistan_medicine_safety/en (accessed September 20, 2019).

WHO. 2014. Regulatory system strengthening for medical products. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21456en/s21456en.pdf (accessed April 29, 2019).

WHO. 2015a. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: Foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2015b. WHO’s first ever global estimates of foodborne diseases find children under 5 account for almost one third of deaths. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-12-2015-who-s-first-ever-global-estimates-of-foodborne-diseases-find-children-under-5-account-for-almost-one-third-of-deaths (accessed May 3, 2019).

WHO. 2017a. Review of the member state mechanism on substandard/spurious/falselylabelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2017b. A study on the public health and socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2017c. WHO global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2019. Malaria. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria (accessed November 18, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-a. WHO global surveillance and monitoring system.https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/surveillance/en (accessed December 23, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-b. WHO role. https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/role/en (accessed April 29, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-c. Working for better health for everyone, everywhere. https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/who-brochure (accessed April 29, 2019).

World Bank. 2019. Employment in agriculture (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sl.agr.empl.zs?end=2018&name_desc=false&start=1991&view=map (accessed May 3, 2019).

Xiu, C., and K. K. Klein. 2010. Melamine in milk products in China: Examining the factors that led to deliberate use of the contaminant. Food Policy 35(5):463–470.

Xu, L., H. Gao, K. I. Kaitin, and L. Shao. 2018. Reforming China’s drug regulatory system. Nature Reviews: Drug Discovery 17(12):858–859.