3

Global Efforts to Strengthen Regulatory Systems

The recent work of the Food Epidemiology Research Group, the World Bank’s The Safe Food Imperative, and World Health Organization (WHO) publications on falsified and substandard medicines discussed earlier in this report have had the welcome consequence of drawing attention to regulatory systems problems in low- and middle-income countries. Unsafe food kills over 400,000 people a year, disproportionately children, and costs the world’s economy $110 billion in both treatment and lost productivity (Jaffee et al., 2019; WHO, 2015). Falsified and substandard medicines cause about 70,000 excess deaths from childhood pneumonia and account for between 2 and 5 percent of malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa alone (WHO, 2017). These are powerful numbers that put the public health significance of unsafe food and poor quality medicines in context. These problems take a toll on developing countries similar to that of HIV, malaria, or tuberculosis.

Better clarity on the size of a global problem should engender a proportionate, global response. Yet, much of the immediate reaction to these reports has emphasized local solutions from the need for African consumers to demand food safety from their governments to the responsibility of national governments for market surveillance and enforcement of regulations (Crossette, 2019; UN, 2017; Whitworth, 2018). No one could deny the importance of the consumer, the regulator, or the political leader in solving this problem, but their actions cannot reach their full value if the global environment does not foster product safety.

Global health and development organizations, including the United Nations (UN) agencies, development banks, and major donors have

considerable power to influence policy in ways that encourage functional regulatory systems. This chapter recommends actions these organizations1 can take to strengthen product safety systems. It also discusses how circumstances beyond the control of a single country influence local markets for food and medical products.

THE ROLE OF AID

As the previous chapter stated, donor assistance for health now makes up a relatively small piece of total health spending in most of the world, making the effectiveness of the remaining contribution crucial, especially to the donors. Since the 1990s, if not earlier, there has been concern that the manner in which foreign aid is delivered can do unintentional harm in recipient countries. Such problems can be logistical, as when donor contributions are redundant or not in line with local needs. Coordinating donations from multiple sources also adds to the burden on scarce accountants and managers in recipient countries.

Aid effectiveness has been a particular interest of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which convened the 2005 forum that produced the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD, n.d.-a). The Paris Declaration set out a road map for the future of aid, emphasizing coordination among donors, aligning with the host country’s priorities, and the need for donors and recipients of aid to hold each other accountable (OECD, n.d.-a). Subsequent initiatives in the same vein (the 2007 International Health Partnership, the 2008 Accra Agenda for Action, the 2011 Busan Partnership for Effective Cooperation) have reaffirmed these principles and the goal of making aid more predictable, efficient, and useful (Osondu and Yamey, 2019).

Untying Aid and Building Institutions

Aid effectiveness has two features especially relevant to the discussion of regulatory systems. The first is the untying of aid, meaning removing conditions that required aid recipients to procure goods and services through the donor country (OECD, n.d.-b). Such conditions can increase the cost of a project 15 to 30 percent, more if food is procured (Meeks, 2017; OECD, n.d.-b). Procurement conditions in development also limit the usefulness of foreign assistance in building the local economy, something especially shortsighted in the case of food and medical products (Meeks, 2017).

Members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee have committed to untying aid in the least developed countries and in heavily

___________________

1 Described increasingly as “development partners” (Digital Campus Moodle, 2016).

indebted poor countries; progress toward this goal has been consistent and good (OECD, 2019). Despite recent drops, over 87 percent of relevant aid is untied (OECD, 2017). Fully realizing the spirit of the move away from tied procurement, meaning using donor money to build the local economy, will depend on functional regulatory systems to ensure that products produced locally are of good quality (IADB, 2017).

Building regulatory systems is part of a larger question of institution building, mentioned in the Paris Declaration and Accra Agenda (OECD, n.d.-a; UN, n.d.). To better build institutions, donors committed to channeling 55 percent of aid through local financial systems, though this goal has not been met (OECD, 2015).

Despite a theoretical commitment to institution building, donors, especially bilateral donors, continue to spend in ways that, far from supporting institutional development, can undermine it by setting up parallel management and reporting systems for their projects, for example (de Ronzio, 2016). Instead of investing in the long-term development of capacity, something of a fuzzy concept, most aid projects measure outcomes they can realistically expect to change within a few years (de Ronzio, 2016).

Donors, for their part, have understandable reasons for such action. In some ways, ceding control of the taxpayers’ money to a foreign government, especially one not known for strong financial management, could be seen as poor stewardship. An interest in measurable, short-term outcomes, things like the number of bednets delivered or farmers trained in Good Agricultural Practices, comes from a culture of accountability (de Ronzio, 2016). Decision makers in donor countries know that they will have to justify their spending to the public, driving a tension between “results today and capacity tomorrow” (Kenny, 2016). As a World Bank analysis explained, “in their need to show results, donors … shirk on provision of the public sector human and organizational infrastructure essential for the country’s overall long-term development” (Knack and Rahman, 2007).

Benchmarking Regulatory Systems

Recent attention to measuring the capacity of regulatory systems could help adjust the donor calculation to encourage spending on building institutions, specifically on building the institutions that protect the safety of food and medicines, thereby increasing options for local procurement. A valid benchmarking tool can put clear parameters on the otherwise amorphous concept of institutional capacity. There is already good consensus on the jobs regulatory authorities need to do to ensure product quality, as reflected in international assessment tools.

The World Health Organization Global Benchmarking Tool for National Medicines Regulatory Systems

The Global Benchmarking Tool was developed in response to a 2014 World Health Assembly resolution on strengthening regulatory systems for medical products (WHA, 2014). The current iteration of the tool was developed over several years after consultation with WHO member states and with the public, as well as meetings with experts from regulatory authorities around the world (WHO, n.d.-g). The tool can be used to evaluate agencies regulating medicines and biologics; expansion to include devices, diagnostics, blood, and blood products are in development (WHO, n.d.-g).

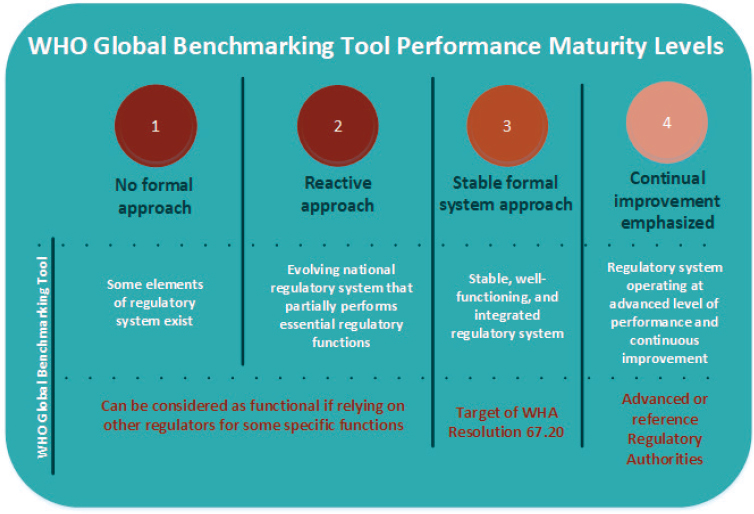

Results of the benchmarking assessment designate medicines and biologics regulatory authorities at one of four maturity levels, a concept carried over from the International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO’s) guidance on quality of organizations. Figure 3-1 describes these levels, linking them to ISO standards, and noting the level 3 cut point that countries are meant to aim for.

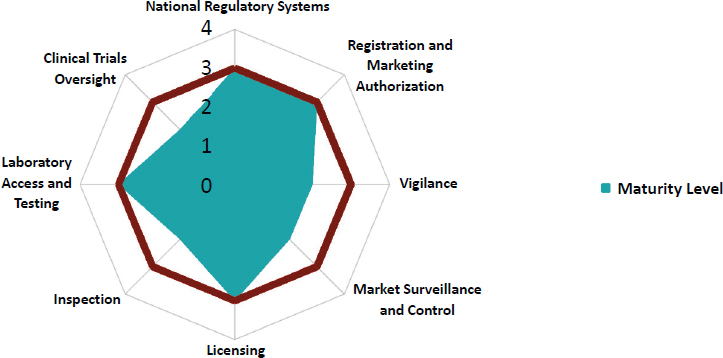

In short, WHO benchmarking identifies the strengths and areas of improvement of regulatory authorities and their overall maturity level. The benchmarking process involves independent assessors’ nine key functions: national regulatory systems (generally dealing with legal provisions and enforcement), registration and market authorization, vigilance, market surveillance and control, licensing of establishments, regulatory inspections, laboratory testing, oversight of clinical trials, and lot release of vaccines.2 During the evaluation, the assessors collect information on 268 indicators of the system’s function, all of which are described in detail on the WHO website (Khadem, 2018; WHO, n.d.-g). The agency’s relative performance in each area gives its leaders indication of where to focus efforts for improvement. Figure 3-2 gives graphical representation of a hypothetical agency’s performance; the red line indicating the level three target, making it easier to visualize the agency’s relative gaps.

The outcome of the benchmarking assessment informs a 5-year institutional development plan wherein agencies identify how they can improve on their relative weaknesses (Khadem, 2018; Ward, 2019). This plan should have provisions for annual and semi-annual progress reviews; an assessment team will review progress after about 2.5 years, and after 5 years, the benchmarking exercise will be repeated (Khadem, 2018).

___________________

2 The first eight functions are common to all medical products regulation, but lot release, which applies only to vaccines, is sometimes described as the “non-common” function.

NOTE: ISO = International Organization for Standardization; WHA = World Health Assembly; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: Khadem, 2018.

Food Safety Systems Benchmarking

Assessment of the food safety system is more complicated than the analogous process for medicines, especially in low- and middle-income countries where there may be multiple systems serving different markets. One system is that of the informal market, over which regulators have, almost by definition, no control. (Informal markets are discussed further in Chapter 5.) Many low- and middle-income countries also have a thriving production system for food exports. Between 2001 and 2016, export of high-value foods (animal-source foods, fresh produce, spices, and nuts) from low- and middle-income countries increased four-fold (Jaffee et al., 2019). This thriving market is credited to improvements in production and efficiency, as well as in the management of the export food market, with both the government and the private sector investing in meeting requirements for market access (Jaffee et al., 2019).

SOURCE: Khadem, 2018.

Controls on the domestic food market are less predictable and harder to measure, described in The Safe Food Imperative as “sporadic and reactive, coming in the wake of major outbreaks of foodborne disease or food adulteration scandals” (Jaffee et al., 2019). In some ways, this makes the benchmarking process even more valuable, as the assessment can motivate investment in the food control system. The challenge of using benchmarking to this end is that there is no comprehensive, publicly available, standardized assessment tool relevant to low- and middle-income countries (Jaffee et al., 2019). The Safe Food Imperative commented on this problem, noting that, while detailed assessments of the systems have been done in many low- and middle-income countries, the findings, sometimes even the criteria assessed, are sensitive and not shared, “perhaps because of concerns about how the media or public would react to documented shortcomings” (Jaffee et al., 2019). Assessments of regulatory systems are sensitive, but this committee believes openness about the results is the best course of action. Furthermore, because food safety touches on many different fields, there are a variety of benchmarking tools that touch on different aspects of food safety. A comprehensive food safety benchmark analogous to that provided by the WHO Global Benchmarking Tool is desirable, and may be best approximated by the WHO and the FAO Food Control System Assessment Tool.

The Food Control System Assessment Tool

The WHO and the FAO Food Control System Assessment Tool can provide a useful benchmark for regulatory competence (FAO, 2019). The contents of this tool share many similarities with the Global Benchmarking Tool, including an emphasis on continuous improvement, assessment of key functions, and a final rating for the strength of the system (though this is not a rating for the agency or agencies involved) (Caipo, 2019; FAO and WHO, 2019b).

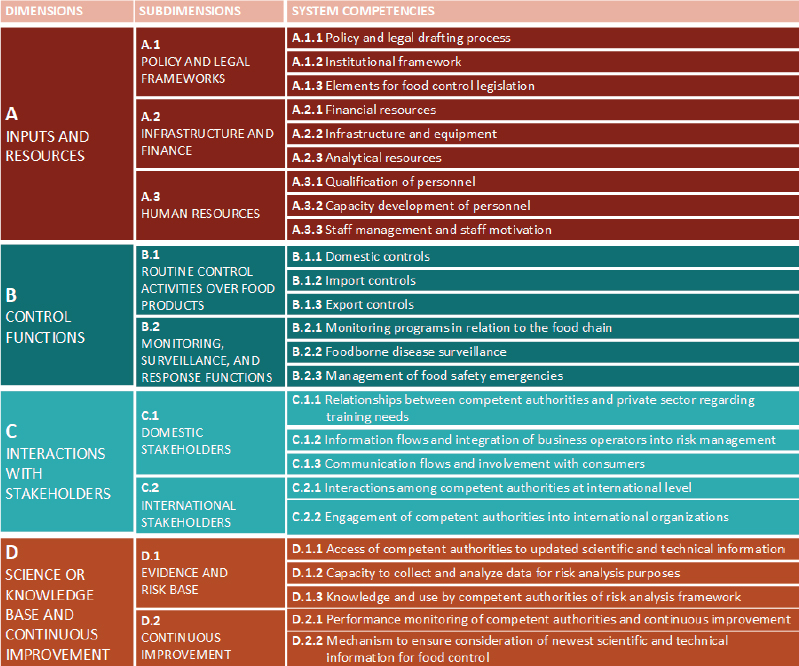

The Food Control System Assessment Tool was developed in 2014, building off publicly available assessment tools from the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture, the World Organisation for Animal Health, and the International Plant Protection Convention (FAO, 2014; FAO and WHO, 2019b). Figure 3-3 shows the four dimensions assessed in the evaluation (inputs and resources, control functions, interaction with stakeholders, science and knowledge base and continuous improvement), as well as the ways these dimensions are subdivided and the competencies assessed. Part of the process relies on self-assessment from people working in the regulatory agency, though assessors from the WHO, the FAO, or both will facilitate the process (Caipo, 2019). As with the Global Benchmarking Tool, scores on the WHO and the FAO food control assessment are meant to help regulators identify weaknesses and develop plans for improvement (FAO, 2019).

The Food Control System Assessment has only been publicly available since July 2019 (FAO and WHO, 2019a). Reports from as early as 2014 indicate that it was pilot tested in the Gambia, Indonesia, Iran, Malawi, Moldova, Morocco, Sierra Leone, Zambia, and Zimbabwe; results of these assessments are confidential, and sharing them is at the discretion of the participating country (FAO, 2014; STDF, n.d.b).3 Coverage of a recent assessment in Indonesia, for example, commented on relative strengths in risk analysis but problems integrating information across different food safety agencies (TEMPO.CO, 2018). Like the Global Benchmarking Tool, the assessment is designed to produce a clear list of priorities and a strategy for improvement, and to give countries a baseline from which to monitor their progress (STDF, n.d.b). This exercise should, in turn, “help governments direct and integrate national investment with donor assistance” (STDF, n.d.b). Repeating the processes on a predictable timeline, every 5 years, for example, can help countries monitor their progress and identify new priorities for improvement.

___________________

3 This text has changed since prepublication release of the report.

Other Food System Evaluations

One advantage of the WHO and the FAO Food Control System Assessment Tool is that it considers the full food safety system in a country. Other evaluations serve similar purposes for parts of the system. Assessment of animal or plant health can, when taken together, give a good picture of the food controls in a country.

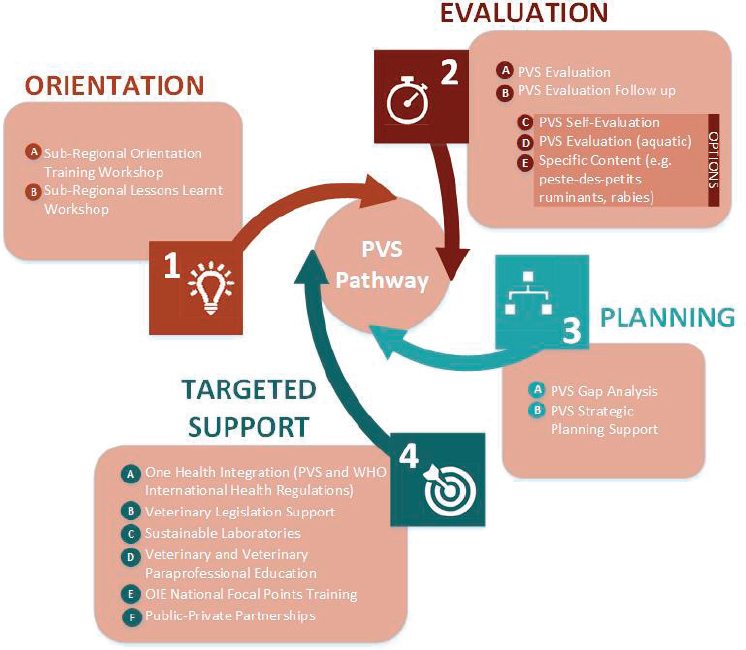

The World Organisation for Animal Health Performance of Veterinary Systems Tool

In 2007 the World Organisation for Animal Health (known by the historical acronym OIE) released its Performance of Veterinary Services Pathway (OIE, 2017). Now in its sixth edition, the tool is published online (OIE, 2019). Though not a total food system assessment, the tool assesses veterinary services and health, which are relevant to the safety of high-risk, animal-source foods (Jaffee et al., 2019). Like other benchmarking assessments it brings external assessors to a country; the assessors evaluate the system, identify key gaps, and return for follow-up evaluations (Jaffee et al., 2019). (Figure 3-4 presents the steps in the evaluation cycle.) The gap analysis is organized according to relevant competencies in trade, animal health, veterinary public health, veterinary laboratories, and management and regulatory services (OIE, n.d.-b). It also facilitates the calculation on an annual budget and a separate budget for exceptional expenses (OIE, n.d.-b).

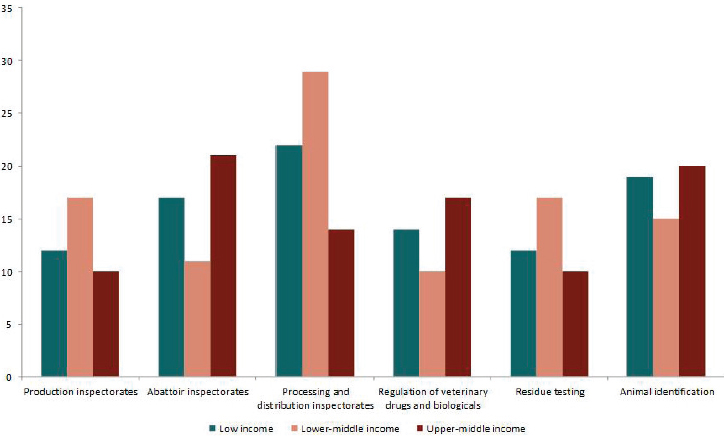

The OIE tool positions veterinary services as a global public good, necessary for both social and economic well-being (OIE, 2019). Final assessments are not public documents, though a growing list of countries has authorized the OIE to publish their gap analyses (Jaffee et al., 2019; OIE, n.d.-a). Development partners may also have access to the assessments, as the World Bank did, reporting on some aggregate information in the 2019 The Safe Food Imperative (Jaffee et al., 2019). Their analysis concluded that, across low- and middle-income countries, surveillance for disease and food safety is deficient, and traceability is negligible (Jaffee et al., 2019). As Figure 3-5 indicates, a large share of upper-middle-income countries perform adequately in key functions but still have strong capacity in only a minority of areas (Jaffee et al., 2019).

The International Plant Protection Convention’s Phytosanitary Capacity Evaluation

The International Plant Protection Convention (a treaty overseen by the FAO) has a plant health evaluation called the Phytosanitary Capacity Evaluation Tool that may be analogous to the OIE tool. This evaluation differs from the FAO and the OIE assessments discussed previously in that,

SOURCE: OIE, 2019.

although it involves an external facilitator, the process and substance of the evaluation are left largely to the participating country, even in determining what pieces of the national plant health system to evaluate (FAO, 2017a). As with the other assessments, the results are confidential. The items assessed are also not public, out of concern that applying the evaluation without proper facilitation would lead to invalid conclusions (FAO, 2017a). Broadly speaking, the tool has 13 modules, each one dealing with a different aspect of a national plant health system, including its legislative protections; resources; surveillance and reporting capacity; import regulatory system; and export, re-export, and transit systems (FAO, 2017a).

SOURCE: Jaffee et al., 2019.

Assessment Results and Planning

The results of benchmarking assessments, be they those discussed in this chapter or others, are valuable to many stakeholders. First, they give the regulatory agencies, and the citizens to whom they are accountable, an idea of how well the system works. These results also allow for comparison between regulatory authorities. Such comparison can be especially useful for countries pursuing work sharing. By giving a common set of criteria and functions to aim for, benchmarking can facilitate harmonization (Ndomondo-Sigonda et al., 2017). The results also send a signal about an agency’s ability to ensure quality food and drugs for domestic and international use.

In 2018, about a quarter of WHO member states had medicines regulatory authorities functioning at level three or higher (Khadem, 2018). Roughly the same proportion were at level two; half were at level one (Khadem, 2018). Less is known about the results of various food control assessment tools. Still, a review of FAO assessments in South and Southeast Asia identified common problems, including lack of clarity on which standards are voluntary and which are mandatory; laboratories not being accredited; poor coordination and overlapping mandates among food regulatory agencies; laws and processes not made with attention to risk; and a lack of reliable data (Jaffee et al., 2019).

Countries need to know how their regulatory systems are performing relative to other countries’ agencies and over time. But simply measuring performance will not encourage progress in itself. Benchmarking should also fit into a larger institutional development plan. The assessment is the first step; strengths and weaknesses identified in this assessment inform the next step: drafting of an institutional development plan. This is a short-term (roughly 5-year) strategy that breaks down the tasks needed for an agency into specific steps and priorities. This plan should set out terms for monitoring and for corrective actions when targets are not met on time.

The results of the benchmarking assessment, as well as the budget and the institutional development plans they inform, should then be shared with a coalition of interested partners, including both public- and private-sector partners who can help with capacity building. The WHO has pilot projects using a coalition model to support regulatory agencies in Bangladesh and in sub-Saharan Africa (WHO, 2019a,d). The weaknesses identified in the assessment are the areas donors can target their support. For example, if a country was short of meeting the Global Benchmarking Tool’s level three cut point in inspection and vigilance, then those functions would be the target of donor funding.

Recommendation 3-1: Development partners, including multilateral and bilateral donors and private philanthropic organizations, should encourage countries’ participation in regulatory benchmarking assessments, the development of institutional development plans, and reports on progress against those plans. To this end, assistance should be targeted to priorities identified in benchmarking assessments and the related institutional development plans.

Benchmarking of regulatory systems is a valuable process in itself. It brings external assessors to a system and gives the agency’s leaders a time to reflect on priorities and think strategically about improvement. The results of the assessment facilitate harmonization and allow for comparison among agencies and within the same agency over time. The tools also translate the daunting and sometimes vague concept of regulatory performance into concrete tasks, and provide for regular checks on progress (Roth et al., 2018a). Benchmarking also has a valuable self-assessment component. The international team responsible for the Global Benchmarking Tool evaluation also facilitates the participating agency’s staff to make institutional development plans (Branigan, 2019).

None of these benefits can be realized, however, unless countries choose to participate in the assessment. This is precisely why an incentive in the form of donor assistance would be valuable. Donors can encourage participation by tying their support to the agency’s institutional development

plan. This strategy would magnify the value of the donor contribution, by using it to influence recipient countries to go through a benchmarking assessment. It would also help ensure that the aid provided is in line with local priorities. The point of the institutional development plan, after all, is to identify priority actions that can improve the agency in the next 5 years. Incorporating the results of the benchmarking assessment into a concrete and time-bound plan can also help drive progress, raising the visibility of the regulatory agency within government (Kaddu et al., 2018). Ministers of health and agriculture have many competing priorities, after all. Measurement, assessment, and re-assessment of regulatory gaps can help keep up momentum for investing in regulatory systems even in the face of other demands.

An additional and desirable level of accountability would come from making the results of the assessment public, something none of the assessments require. The committee recognizes the reasons why agencies might resist disclosing their results. Food and medicines regulation can be highly sensitive topics, and agencies might have reasonable concerns about how any shortcomings would be perceived in the press (Jaffee et al., 2019). The organizations conducting the benchmarking assessment, for their part, cannot compel sovereign governments to share information with the public. However, the global expectation of transparency—and support from key donors—could create significant pressure on governments to do so.

A strong argument for making benchmarking assessments public is that transparency can influence policy (Hale and Held, 2011). The process can help governments develop functioning, integrated regulatory systems that benefit their citizens and consumers around the world (Jaffee et al., 2019). Donors can use their influence to encourage this process. For example, countries that may resist sharing their results might be persuaded to allow partial public access or access to certain intermediaries. Development partners such as the World Bank have selective access to the OIE veterinary assessments, for example, as this information can inform the Bank’s investments in a country (Jaffee et al., 2019). In the same way, the committee envisions donors, acting individually or as a coalition, using the gaps identified through benchmarking and the related institutional development plans as a roadmap for their support. Working together toward progress on the institutional development plans also gives donors a chance to encourage their host country counterparts to publicize progress and eventually to make results public.

It is in the best interest of all development partners that regulatory systems in low- and middle-income countries perform better. Investing in these institutions is a worthy priority for donors and one entirely in line with principles of aid effectiveness. It would also contribute to more vigorous

local markets in low- and middle-income countries, something that would benefit everyone.

Considerations in Procurement

The Paris Declaration emphasis on untying of aid was meant to improve efficiency and value for money (Clay et al., 2009). The more recent move toward universal coverage makes these concerns even more pressing. Countries, including those middle-income countries transitioning away from multilateral funding, are, because of universal coverage, now responsible for the purchase of more and varied types of medicines (Silverman et al., 2019; Tatay and Torreele, 2019; Wagner et al., 2014).

Procurement poses many challenges for buyers in low- and middle-income countries. Regulatory hurdles, such as the process required for registration in a country, can make procurement less efficient (Silverman et al., 2019). Registering more and different types of medicines puts a burden on the regulatory agency, often far exceeding its capacity in low- and middle-income countries (Roth et al., 2018a).

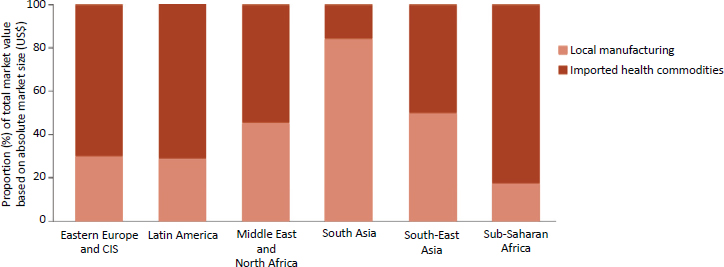

Modern manufacturing can also make it difficult to weigh the essential procurement question of value for money. As Figure 3-6 shows, some parts of the world (South Asia for instance) have considerable local manufacturing, while most medical products used in sub-Saharan Africa are imported (Silverman et al., 2019). Ensuring quality for imported products is challenging for any regulatory agency, and especially so for ones with fewer resources.

As the previous chapter explained, the WHO Prequalification Program provides assessment, inspection, and ongoing re-inspection of manufacturers and consistency testing and quality control for certain vaccines, medicines, and other medical products. As such, it can be a boon to procurement agencies, acting as a proxy regulatory approval, something especially valuable in managing the combination of limited regulatory capacity and foreign suppliers. To be clear, however, the WHO does not act as a supra-national regulatory agency through prequalification (Stahl, 2013). Prequalification does not provide the key regulatory responsibility of market authorization, though some countries may use it for that purpose (Stahl, 2013).

The Prequalification Program is also one of the best tools for building capacity in medicines regulation. Every step of the prequalification assessment, including dossier review and site inspections, is conducted by teams made up of WHO staff, regulators from advanced agencies, and regulators from the countries where the prequalified products will be used (WHO, n.d.-a). This allows for hands-on training by conducting the reviews, a valuable exercise for the regulators involved. Furthermore, regulators in the

NOTE: CIS = Commonwealth of Independent States.

SOURCE: Silverman et al., 2019.

home country of the manufacturer applying for prequalification can join prequalification inspections, even if they are not part of the assessment team (Stahl, 2013). Regulators from developing countries can also participate in a three-month rotating position at WHO headquarters to get experience of prequalification and deeper knowledge of other areas that influence medicines regulation (‘t Hoen et al., 2014).

Capacity building also extends to WHO’s prequalification of quality control labs, which provides technical assistance and management audits to help ensure the labs can operate to international standards (WHO, n.d.-e). The program also has been found to have positive spillover effects on manufacturing, with production lines for both prequalified and non-prequalified products benefiting from manufacturers’ participation in the program (WHO, 2019b).

WHO prequalification started in 1987 as a check on the quality of vaccines procured through UNICEF or other UN agencies (Dellepiane and Wood, 2015; WHO, 2013). In 2001 the program expanded to include medicines for HIV procured through UNAIDS and other UN agencies; it quickly expanded to include treatments for tuberculosis and malaria (Stahl, 2013). Today about 1,700 products have prequalification, including treatments for hepatitis and diarrheal disease. Some neglected tropical diseases are included in prequalification, as are various vector control products, diagnostic kits, immunization devices, and reproductive health products (WHO, 2019b). By 2019 estimates, the Prequalification Program enables a market of about $3.5 billion annually, allowing an additional 340–400

million people to access treatment they might not otherwise have had (WHO, 2019b, n.d.-d).

As of late 2019, there were 553 medicines on the WHO prequalified list, the vast majority treatments for HIV, tuberculosis, or malaria (WHO, n.d.-b). The types of products listed for prequalification reflect the demand of the program’s main clients: UN agencies, the Global Fund, and large donors. There is room to make the program more useful to other large buyers of medical products, including low- and middle-income country governments and the private businesses that do a great deal of procurement in those countries (Silverman et al., 2019). To this end, the Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines recommended the expansion of WHO prequalification to include more medicines (Wirtz et al., 2017). The most recent meeting of the International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities called for the same, citing the program’s ability to improve access to quality-assured medicines, and its role in meeting the increasing demands of universal coverage (ICDRA, 2018). If given the option of buying from prequalified suppliers, large procurement agencies could reliably use their purchasing power to promote medicines quality.

Recommendation 3-2: The World Health Organization should expand prequalification to include treatments for cancer, diabetes, and other diseases with a high global burden.

The WHO Prequalification Program provides a global public good. It also improves health, increasing the supply of good-quality, affordable medical products in low- and middle-income countries (Unitaid, n.d.). A larger list of reputable, quality-assured medicines would give procurement officers a tool to navigate an otherwise murky market. Expanding the list of prequalified products to be more in line with the burden of disease in aid recipient countries would also help countries ensure their medicines budgets are going to reliable products. As the move to universal coverage increases the burden on this budget, the question of value for money will be even more important. Ultimately, good procurement protects the population from the risk posed by poor quality medicines.

Prequalification is also a proven investment in building capacity for medicines regulation (Dellepiane and Wood, 2015; WHO, 2013). Through its design the program takes advantage of technical depth at advanced regulatory agencies (those benchmarked at level four or higher), without duplicating their work, though products approved by these agencies are given an abridged review in the prequalification process (Rägo, 2012). The Global Fund guidance on procurement also allows procurement of products approved for use by advanced regulatory agencies (The Global Fund, 2018).

Expanding WHO prequalification could also help ensure a vigorous market for quality-assured generics. Prequalified companies increase their chances of international procurement; they may also expand their local markets. This is a potential benefit; uncertain demand is difficult for honest manufacturers to manage. High variability impedes efficiency and scale; it also makes for higher transaction costs that are then passed along to consumers (Silverman et al., 2019). A 2019 assessment found that every dollar spent in running prequalification returns 30 to 40 times that amount in savings during procurement and by leveling the playing field to allow good manufacturers in low- and middle-income countries entry to international markets (WHO, 2019b).

In its 5-year plan to help build regulatory systems, the WHO cited strengthening and expansion of prequalification as a strategic priority (WHO, 2019a). To this end, the 5-year plan discussed ways to improve awareness of the program, especially the capacity building piece that regulators might not be aware of, and the spillover benefits to local manufacturing (WHO, 2019a). Regarding the expansion of the prequalification list, the 5-year plan highlighted in vitro diagnostics and vector control products (WHO, 2019a). The committee supports this plan and sees this recommendation as part of a global consensus on the value of the program (ICDRA, 2018; Wirtz et al., 2017). At the same time, it encourages WHO authorities to look beyond products associated with HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, and reproductive health. As of late 2019, only about 17 percent of products on the WHO Model Essential Medicines List have even one prequalified supplier.4

The choice of medicines and the order at which they are added to the program is a topic for further discussion. The information available in the Global Burden of Disease reports regarding both the prevalence and relative harm of different conditions would be part of this discussion (IHME, n.d.). Products for smaller but important markets, such as neglected diseases, should also be considered. There is also clear demand for any product where a third or more of the total market by volume is subject to global procurement. Medicines that present a particular challenge to regulators because of the complexity of manufacturing would also be good candidates (‘t Hoen et al., 2014), as would anti-infectives since the risk of drug resistance makes the quality of these products a global public good.

Expansion of the prequalification program would improve access and reduce costs of whole families of important products (e.g., antidiabetics and cancer treatments). It would also have other helpful effects. The use of poor quality antimicrobials, for example, contributes to resistance, a problem of serious public health consequence around the world (IADB, 2017). Prequalification of those antimicrobials at high risk for quality problems,

___________________

4 Percentage calculated from WHO, 2019c,e.

beta-lactams for example, might also be a strategy for reducing resistance (Fair and Tor, 2014; Kelesidis and Falagas, 2015).

One important feature of the Prequalification Program is its ongoing quality control efforts, including re-inspection, quality monitoring, field sampling and testing, and monitoring of quality control laboratories (WHO, n.d.-c). The expansion envisioned in this report would give considerable attention to these measures taken after listing. Such post-approval quality control is not emphasized as part of the expansion of prequalification described in the WHO’s recent strategy document, although there is attention to building capacity for post-market surveillance in general (WHO, 2019a).

Critics of this strategy might maintain that prequalification was meant to be an interim solution as countries develop their regulatory and procurement systems (Dellepiane and Wood, 2015). Nevertheless, today the program fills an important void, not just in the assessment and quality control for certain drugs, but in capacity building for both regulators and manufacturers. Therefore, the committee concurs with the Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines, that more types of products be included in prequalification, “at least until … the global generic market has developed sufficient capacity” to meet the increased demand universal coverage will bring (Wirtz et al., 2017).

The development of capacity is central to the Prequalification Program and to this recommendation. One aspect of capacity building is increasing ability—that of regulators, of manufacturers, of procurement programs—to operate well. WHO prequalification has, by design, considerable emphasis on this aspect of capacity building, as discussed earlier in this section. It is important to remember, however, that building capacity also refers to improving the total resources available for a job. For some agencies, this increase in capacity comes mainly from sharing information to avoid duplication of work; international harmonization and regulatory convergence (discussed later in this report) are tools to the same end. Prequalification of medicines provides a global public good, even beyond its staff development component. Expansion of the program would increase the public good and allow regulatory and procurement agencies to work more efficiently.

The committee recognizes that the products on the prequalification list to date are those procured by international agencies, whereas procurement of medicines for cancer and other chronic diseases are mostly domestic responsibilities. National procurement cannot command the same negotiating power as major donors placing pooled orders (Tatay and Torreele, 2019). At the same time, there is growing interest in helping countries respond to the challenges of noncommunicable diseases. The Defeat NCD Partnership,

for example, is a group of governments; civil society; academic, philanthropic, and research organizations; private businesses; and multilaterals committed to fighting noncommunicable disease, especially in the 49 least developed countries (The Defeat-NCD Partnership, n.d.-a, n.d.-c). Its financing facility aims to help countries create fiscal space for related efforts, with additional donor funding, bonds, and other tools (The Defeat-NCD Partnership, n.d.-b). The donor initiative Resolve to Save Lives is similarly committed to expanding access to anti-hypertensives globally (Vital Strategies, n.d.). Some of these programs are still in early stages, and expanded prequalification might better position them to procure large orders as the Global Fund does.

Expanding prequalification also puts a burden on the WHO and other participants in the program. Some of that burden will come in the form of increased demand for expertise. Prequalification review depends on the contributed short-term expertise from regulators from advanced agencies5 (WHO, n.d.-f). Expansion of prequalification will increase the demand for such service, meaning more regulators asking for time away from their routine duties. The FDA and other level four agencies may need to adjust their staffing projections to ensure they can do their part to meet this demand.

There is also a direct financial burden on the WHO. Manufacturers are charged user fees to participate in prequalification; before user fees were introduced (in 1999 for vaccines, 2008 for diagnostics, and 2013 for medicines) the only donors to the program were UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Unitaid (WHO, n.d.-h). In an effort to improve the program’s sustainability, the WHO revised its fee structure in 2017 (WHO, n.d.-h). Under the new structure user fees are meant to cover about half of the program’s operating costs, with fees waived for important products with small markets (WHO, n.d.-h). The use of fees to support prequalification also brings challenges, especially for products with small markets and for which the volume under global procurement is small.

Ideally, this report and the wider consensus about global public goods of which it is a part, would encourage the United States and other rich countries to pay their full assessed contributions to the WHO, thereby alleviating some of the financial strain of this recommendation. Advanced regulatory agencies (those benchmarked at WHO level four) also have a role in increasing resources for prequalification. Staff from these agencies support prequalification by taking part in the dossier reviews and inspections. As much as possible, they should advocate for more support for it from their agencies and from their countries’ aid organizations.

___________________

5 Those performing at level four or higher on the Global Benchmarking Tool assessment.

Data and Standards

Expanding WHO prequalification and benchmarking regulatory systems both serve the goal of improving efficiency and access to good-quality products, something of crucial importance to under-resourced agencies. These recommendations, if implemented, could bring new products into low- and middle-income country markets, new opportunities for capacity building, and a new, impartial analysis of the regulatory system. There are also ways to improve product safety by making better use of some of the information already collected.

The routine operations of governments, businesses, and nonprofits today produce a great deal of information (Marvin et al., 2016). Unlocking the potential in this information, particularly its potential for public health, remains a challenge, however. Especially in low- and middle-income countries, the systems and skills needed to manage data exceed local capacity (Mathauer et al., 2017). There can also be obstacles in the form of an organizational culture that does not encourage sharing, or even generating, information (Mathauer et al., 2017).

Such reticence is understandable. There is a cost to disclosing information, both directly, in terms of staff time or technical upgrades, and indirectly. Data sharing can be technically difficult because different organizations have different ways of collecting and managing the same or similar information; their data systems are not likely to be interoperable without deliberate attention (Gascó et al., 2018). The decision to share data requires participants to overcome the fear that information could be used against them (Gascó et al., 2018).

At the same time, large datasets can be useful to regulators. The post-market surveillance of medicines, for example, could be made easier by using the information in electronic medical records or the copious, unreported data collected in clinical trials (IRPCV, 2018; Ross, 2014). Making use of these data can be difficult, though. Advanced regulatory authorities are struggling with adjustments to their legal authority and guidelines brought about by so-called big data (EMA, 2019; Martin, 2017).

The idea of big data is applied to food safety less frequently, partly because the information, while just as vast, is scattered among more and disparate sources (Marvin et al., 2016). Simply identifying and linking relevant information from across these sources presents a challenge (Marvin et al., 2016). The technology exists to trace food through the supply chain, with tremendous potential to control foodborne disease. For farmers, especially small farmers in low- and middle-income countries, access and ability to use powerful handheld technology for data collection can be a barrier to traceability, though the best incentives to encourage data collection and sharing at the level of the small farmer are not necessarily clear (Gascó et al., 2018).

Sharing data could change the way regulators work with their counterparts in other countries (EMA, 2019). Regulatory inspections, for example, are a considerable staff burden on both regulators and industry (Rönninger et al., 2017). There is wide consensus that collaboration and joint inspection help control this burden (FDA, 2018d; ICDRA, 2016; IOM, 2012a; WHO, 2012). Similar data standards could help translate this and other principles of regulatory cooperation into action.

Box 3-1 explains what data standards are and why they are important. Common rules on how to collect and store data help industry manage risks (Davidson, 2016). Data standards are also the foundation of the regulatory agency’s public health risk ranking. The development of tools to rank and assess risks is central to a risk-based regulatory system (IOM and NRC, 2010). Information about risks also facilitates work sharing among regulators, a topic discussed more in Chapter 5.

When resources are scarce, the imperative to make good use of what is available increases. For regulatory agencies this means facilitating the sharing of data among different government agencies and industry. Sharing data means organizing a vast amount of information. There are tradeoffs when collecting such information, between accuracy, ease and speed of collection, and the expense of the undertaking (Martin, 2017). Donor funding could minimize the technical obstacles and expense of data sharing, helping to tip the balance of tradeoffs in favor of openness.

Recommendation 3-3: Development partners, including multilateral and bilateral donors and private philanthropic organizations, should support countries and regional organizations in pursuing greater collaboration for regulating food and medical products. This collaboration can include harmonization and mutual recognition of data or standards, equivalence agreements, and regulatory reliance.

Information sharing “is key to reaping the public value from all kinds of data” (Gascó et al., 2018). Particularly in food safety, no one organization has enough information to ensure traceability through the supply chain (Susha et al., 2019). Data sharing also produces a public good. The information generated can inform public policy and risk-to-benefit analysis; it can be used to answer valuable research questions (Gascó et al., 2018). Box 3-2 describes one such data-sharing program, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Global Branded Food Products Database.

The technical costs of data sharing, while by no means the only barrier, are a serious obstacle to regulatory collaboration. By providing an interoperable infrastructure and data standards, donors could help overcome the initial cost of data sharing, magnifying the value of their contribution.

Sharing information also depends on strong relationships among collaborators (Gascó et al., 2018). Providing data standards and a common platform could also help build trust among regulators and advance the long-term goal of regulatory harmonization.

THE ROLE OF COMMERCE

The World Trade Organization (WTO) describes trade as, “an engine for inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction” and a force for sustainable development (UN, n.d.). Trade in medical products, and especially in food, can be important in low- and middle-income countries where the domestic market alone cannot stimulate industry or support manufacturing at a sufficient scale to be efficient (Elliott, 2019). In such cases, trade has the potential to improve both livelihoods and the quality of products in the market.

Trade associations have an interest in strong, fair regulatory systems for products their members produce. They can spur interest in strengthening these systems. In Colombia, for example, political interest in free trade agreements translated into increased appropriations to the Invima (the food and drug regulatory agency) starting around 2012 (Guzman, 2019). In 2016, WHO benchmarking established Invima at level four, thereby increasing the market for Colombian products around Latin America (Guzman, 2019). As the former agency head explained, “Invima, as a reference agency of the Americas, is now leading the government efforts to open new

markets for products manufactured in Colombia and improve the country’s competitiveness” (Pharma Boardroom, 2017).

At the same time, movement of food and drugs across borders can aggravate the information asymmetry already inherent in these markets. Inspection and assessment from an independent party can help correct this imbalance, as the WHO Prequalification Program does. Food production, in contrast to medicines, has far more sprawling and complicated supply chains, with multiple, legitimate markets in the same places. As the previous chapter discussed, quality certifications from external third parties are important in food and agriculture, but the balance of benefits and harms, especially to small producers in poor countries, is not always clear (Henson and Humphrey, 2010).

The ability of food producers to comply with international standards, be they Codex standards or the sometimes more exacting private ones, can be used as a proxy indicator of the capacity in a country for managing safety and quality (Jaffee et al., 2019). This capacity does not necessarily permeate the domestic market, however. Certain conditions encourage so-called positive spillovers: when the exported food is also widely consumed locally, for example, or when its production is widespread and not consolidated, when the leading processing companies produce for both domestic and export markets, and when modern retail is common and well developed (STDF, n.d.a). These conditions are not often met in low- or middle-income countries.

Therefore, despite the potential for international food standards to improve food safety, evidence supporting such effects is limited and mixed, probably because the export and domestic food markets in low- and middle-income countries are fairly segregated (Jaffee et al., 2019; STDF, n.d.a). On one hand, some research has found that products failing to meet standards for supermarkets or chain retail are dumped to informal markets (Roesel et al., 2014). The quality of food in informal markets is a concern, since they are the main source of animal-source foods for people in Africa and Asia (Grace et al., 2014). They are also crucial to the economy of low- and middle-income countries. Informal, international trade employs between 20 and 70 percent of sub-Saharan Africa, disproportionately women (FAO, 2017b).

The challenge remains to encourage producers to meet international standards, and to do so in a way that benefits all consumers. Technical assistance can be valuable, and may encourage broad changes to production, such as better farm management (Unnevehr and Ronchi, 2014). But it is difficult to say how much technical assistance for meeting standards helps producers in low- and middle-income countries because so much depends on prevailing market conditions, which can change abruptly (Unnevehr and Ronchi, 2014). Compliance with international standards has a cost,

though the cost can be regained through wider market access (Unnevehr and Ronchi, 2014).

Investing in Safety and Quality

Regulatory enforcement is one means to improve products, but the regulator’s power to change manufacturing practices is limited if the market is not supporting standards. A complete strategy for global action to improve food safety and drug quality must consider the role of market incentives. Large market actors can use their influence to raise product standards. The previous chapter discussed the role of supermarket chains to compel their suppliers to meet third-party standards; the power of large procurement agencies on the medicines market is similar. Market incentives can also be used to encourage producers to invest in quality for the domestic market, as in the Twiga Foods example discussed in Box 3-3.

Investing in quality brings new markets and other opportunities to grow businesses; it can even improve cost-efficiency. The switch from batch processing to continuous manufacturing, for example, allows for a greater volume produced and carries fewer opportunities for contamination (Chatterjee, 2012; Comerford, 2018). Such benefits are not always clear to the people in a position to change business practices. Even when they are, the cost of the capital available from local banks and capital markets in low- and middle-income countries may be too high to make the investment viable (Papadavid, 2017).

Banks in emerging markets usually have especially limited products available to small- and medium-sized businesses, because the credit assessment and costs of making the loan drive up its cost (Abraham and Schmukler, 2017; Abuka et al., 2019; GFSI, 2018). As a result, the small- and medium-sized business owners in developing economies cite access to capital as one of their biggest obstacles (IFC, n.d.-b).

Nevertheless, the private sector in low- and middle-income countries is growing. Private financing to sub-Saharan Africa, for example, has grown in the last decade, but most of this growth has been directed to extractive industries, with two countries (Nigeria and Ethiopia) receiving about two-thirds of all private-sector financing in the region (Tyson, 2017). Only about 12 percent of foreign investment in sub-Saharan Africa is for manufacturing and 2 percent for agriculture (Tyson, 2017). This is unfortunate, as investments in agribusiness and manufacturing have some of the best effects on poverty reduction (Karim and Buckley, 2015). In general, investments in agribusiness and infrastructure have been catalytic in low- and lower-middle-income countries, whereas support for industry and infrastructure has benefited the upper-middle-income countries the most (Massa, 2011).

Development banks and bilateral development finance organizations can lower the cost of equity and make investments in quality more profitable for businesses in low- and middle-income countries. The organizations may do this through concessional financing, meaning loans with considerably more generous terms (in interest or repayment periods or both) than the market would offer (OECD, 2003). They also provide advisory services to companies regarding how to meet international best practices, and how to enter new markets, attract investors, and improve performance (IFC, n.d.-a). It is important to note that capital supplied through development finance is additional to what the market would otherwise supply (FMO, 2016, 2018). And World Bank research has found that, as countries’ incomes increase, the private sector may be able to supply more capital, making their advisory services and support for development of global public goods more prominent (WBG, 2018).There is a role for both types

of products in making improvements to agribusiness and medicines manufacturing in low- and middle-income countries.

Recommendation 3-4: Development finance institutions such as the United States International Development Finance Corporation, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the UK CDC Group, and the European development finance banks should create vehicles to finance producers, distributors, and retailers in low-and middle-income countries interested in meeting regulatory standards. This would involve advisory services and, when appropriate, concessional financing.

Development banks and bilateral development finance organizations increasingly emphasize how well their investments contribute to the poverty reduction, social welfare, and the Sustainable Development Goals (FMO, 2016; Massa, 2011). Investing in quality manufacturing of essential medicines and the safe production of food is in line with these goals and is becoming more common. Box 3-3 describes an IFC program in Kenya to increase farmers’ access to markets. The IFC also offers short-term working capital to food producers certified through the Global Food Safety Initiative as part of its programming to improve food safety and efficient production (GFSI, 2018). Through its MedAccess program, CDC Group, the British development finance agency has lowered the risk to market entry for suppliers of medical products in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (CDC Group, n.d.). MedAccess gives suppliers of certain high-quality medical products a safety net as they introduce new products in their markets, by contracting maximum prices in return for guaranteed sales; if actual sales fall short of the set threshold, MedAccess pays the supplier the difference (MedAccess, n.d.). The committee commends such innovative strategies and encourages wider user of investment vehicles to improve medicines and food safety in low- and middle-income countries. These investments should be evaluated to assess their contributions to product safety and quality; results of such evaluations could be used to make future investment programs more efficient.

This recommendation is concerned with both the advisory services and the lending functions of development finance. First, the organizations can help producers, distributors, and retailers along the supply chain identify future revenue and growth opportunities that could be realized by internalizing higher quality standards. When analysis of future revenue does not favor the change to higher standards, concessionary finance could adjust that calculation.

Tools for Quality Assurance

There are also global companies that are active in quality testing, but are not necessarily expanding in low- and middle-income countries. Food safety testing for pathogens and chemical substances is projected to grow rapidly in Asia over the next 5 years (Global Industry Analysts, 2019), though expansion potential in Africa and Latin America is less clear. Investing in these companies’ expansion into underserved markets could also be a role for development finance.

Quality verification along the supply chain is essential for manufacturers monitoring their processes and outputs; it can also be important further down the supply chain. The assigning of unique identifiers at every step in the food distribution system is essential for traceability (Fernandez, 2019). Barcode serialization in medicines serves a similar goal (Rasheed et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the costs of such measures can be prohibitive for manufacturers, processors, and distributors in low- and middle-income countries (Pisa and McCurdy, 2019).

There are also ways to verify products already in circulation, often at point of entry or point of use (Lalani et al., 2017). Such testing is not a substitute for regulatory checks, or for a full quality assurance process in manufacturing, but is important to the system. In countries with weak regulatory capacity, screening technologies have a complementary role in improving quality (Jahnke, 2018; Lalani et al., 2017). They also provide regulators with much-needed tools for monitoring and can reduce the burden on the central testing laboratories (Roth et al., 2018b). Results from rapid screening assessments can also give regulators a sense of the types of problems common in their markets (Roth et al., 2018b).

Measuring the burden of falsified and substandard medicines, for example, depends on an analytical workflow that can be challenging in low- and middle-income countries (Fernandez et al., 2011). Screening technologies can help manage this workflow. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Counterfeit Detection devices, which can be used to compare the fluorescence of tablets, coating, packaging, food, or other regulated products to a verified sample, are one example of useful screening technologies (Batson et al., 2016; Platek et al., 2016). A European Commission consortium recently developed a handheld scanner that can detect falsified products using radiofrequency (Chen et al., 2016). Other technologies depend on physical, chemical, and microbiological analysis (Ellis et al., 2015; IOM, 2013; Kovacs et al., 2014).

The uptake of these tools at scale in low- and middle-income countries has been limited, however (Nayyar et al., 2015). A recent survey of regulators, manufacturers, distributors, and pharmacists in ten mostly low- or middle-income countries identified, “a technology gap in the development

of affordable, easy to use, and precise screening technologies” (Roth et al., 2018b). The main reasons for this gap include the cost of training to use new technological tools, the cost of equipment and consumable materials, the management of supplies and reagents, and information about the relative strengths and weaknesses of the different methods (Roth et al., 2018b).

There is need for inexpensive, field-ready screening technologies to detect possible food or medicines fraud or contamination, as well as a need to decrease the cost, both direct and associated, with existing technologies (Petersen et al., 2017). Real-time polymerase chain reaction, handheld Raman, and near-infrared, all technologies with great potential to detect medicines fraud, have not been manufactured or distributed at large scale (Batson et al., 2016; Ellis et al., 2015; Fernandez et al., 2011; Hajjou et al., 2013). As a result, the process for manufacturing these technologies and distributing at scale in low- and middle-income countries has not been optimized. Because the market for such screening tools is small, the companies that make them have little incentive to invest in production. A small market also prevents companies from developing a distribution system through which equipment and consumable supplies could be imported. Lack of optimal manufacturing or an infrastructure for distribution creates a vicious cycle where small market size leads to weak incentives to invest, which keeps the market small.

Recommendation 3-5: The United States International Development Finance Corporation, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the UK CDC Group, and the European development finance banks should provide advisory services and concessional financing to manufacturers of quality and safety screening technologies to optimize manufacturing and create stronger distribution systems in low- and middle-income countries.

Quality laboratories will always be an essential part of any product safety system. Rates of false negatives and false positives can vary for different analytic methods, and the use of rapid screening technologies should always take into account their accuracy (Lalani et al., 2017; Pan and Ba-Thein, 2018). At the same time, the promise of rapid technologies is not being realized in the parts of the world that need them most. Improvements to manufacturing and distribution systems for these technologies would foster a stronger market. The strong market would, in turn, help keep the cost of consumables and equipment competitive.

The committee also recognizes that there is still a need for more field-ready, inexpensive screening tools for food safety and medicine quality. Further investment in these tools, especially from the major scientific research funders, both private and governmental, would be welcome. Strong

distribution systems and manufacturing capacity help break the cycle of small markets and weak incentives to invest; they also improve the reach of the many useful tools already developed.

More rigorous assessments of the cost-effectiveness of various screening strategies would also improve the ability of financers and manufacturers to invest in products with the best potential. Research on the cost-effectiveness of screening tools is not as well developed as for medical products, making it impossible to comment on a cost-effectiveness threshold for technologies. Furthermore, a full accounting of cost-effectiveness considers not just the technology but the strategy in which it is deployed. Therefore, a cheap tool might prove cost-ineffective if the associated costs (e.g., staff time, transportation, consumables) are high or if it is deployed inefficiently. Research on the cost-effectiveness of various tools and strategies for their use is needed and would help in determining what screening tools are better suited to different settings.

EXPANDING THE EVIDENCE BASE FOR REGULATORY POLICY

As the previous chapter discussed, regulation of food and medicines corrects a market failure and provides a public good. The agency’s ability to do this job well depends on its ability to use another public good: knowledge. But regulatory science, defined as “the science of developing new tools, standards, and approaches to assess the safety, efficacy, quality, and performance of … regulated products,” is not well-studied (Adamo et al., 2015). Developing methods for understanding risk is a part of regulatory science; it also includes tools for understanding the social and cultural aspects of regulatory decisions and the tradeoffs regulators are obliged to make (IOM, 2012b). The best practices, particularly those suited to small countries, regional consortia, or low- and middle-income countries, are not always clear. For example, the previous section discussed the use of portable screening tools to detect unsafe products in the marketplace. A recent systematic review of these tools found that while there are over 41 portable devices available for field testing of medicines, there is no research commenting on the cost-effectiveness of the various tools or where in the supply chain they should be deployed, the very questions regulators would most want answered (Vickers et al., 2018).

In preparing this report, the committee discussed advances in regulatory science, strategies for capacity building, the balance of work sharing among small or neighboring countries, optimal delegation of tasks from federal to local levels, and the ideal mix of revenue for an agency, all topics discussed further in Chapters 4 and 5. Consistently, it found that evidence to inform specific policy actions was not available. This gap can and should

be corrected. Many of the regulatory agencies in the Americas for example, are less than 25 years old (Barbano, 2019). Formal, regional regulatory collaborations are even newer; the African Medicines Agency is only now forming, and the Caribbean Regulatory System Initiative started in 2014 (Cargill, 2016; IFPMA, 2018). When agencies are new, there is opportunity to start fresh with a system suitable to the context. It would be unfortunate if any of these agencies were to transfer inefficient or outdated practices, either from earlier systems or from advanced agencies, simply because no better options have been identified.

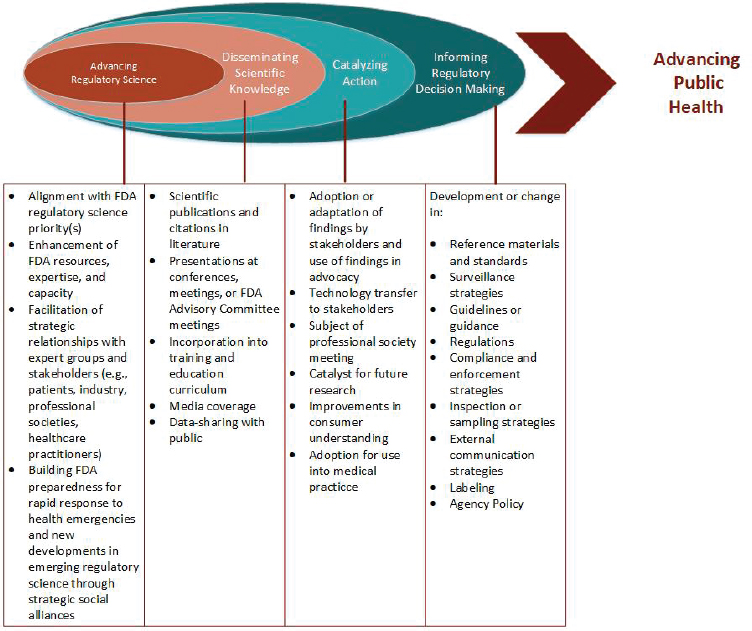

When well-resourced, established agencies face similar knowledge gaps, they have ways to collaborate with academia to advance the science they need. The FDA Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation is a good example of such collaboration. Since 2011, these four centers, based at universities, research priorities identified in the agency’s strategic plan. They also provide a venue for regulatory staff and other experts in the field to work together on topics of shared interest (FDA, 2016, 2018a). Though occasionally criticized for being overly broad, research topics have included drug compounding, pharmacovigilance, the sharing of research data, and the use of computational modeling to understand drug metabolism (FDA, 2016, 2018a,c; Fishburn, 2014). The FDA evaluates the research produced on the basis of how well it informs the agency’s decisions and, ultimately, advances public health (see Figure 3-7).

The most pressing questions in regulatory science in low- and middle-income countries are not necessarily the same as those for the FDA. Nevertheless, the model of dedicated centers or consortia to research priority questions is transferable around the world. These centers, run in collaboration with universities or consortia in low- or middle-income countries, would research product safety needs in their respective regions, as well as public policy questions related to running a regulatory agency, or strategies to improve local manufacturing or quality control. As with the centers in the United States, the dissemination of the knowledge produced would also be an important component of the work.

Recommendation 3-6: The National Institutes of Health, in collaboration with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Agency for International Development, should develop a network of Global Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science for research and capacity building to identify and address the challenges of ensuring food and drug safety in low- and middle-income countries.

In some ways, the FDA would be the more suitable agency to implement this recommendation. It has relevant experience designing extramural collaborations to advance regulatory science; it also has a meaningful stake

SOURCE: FDA, 2018b.

in the cause. The agency has existing connections with regulators in other parts of the world, both because of its involvement in international regulatory networks and through its offices in China, Europe, India, and Latin America. The National Center for Toxicological Research, for example, is a research division of the FDA that encourages collaboration with government, academic, and industry experts in the United States and abroad (FDA, 2019). The FDA also organizes an annual Global Summit on Regulatory Science to discuss the application of basic science for regulatory uses and innovative technologies affecting regulators’ work (FDA, 2019). Still, a 2015 evaluation acknowledged that the agency is not generally a research funder and “has very limited funding to apply to regulatory science research and training,” even domestically (FDA, 2016).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is a research funder; its role as such is part of its strategic reason to invest in Global Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science. Promoting regulatory science is a way to protect the

NIH’s considerable investment in global health. To put it in perspective, between 2017 and 2019 the NIH spent about $200 million a year on malaria research (separate from the almost $60 million a year on malaria vaccine), between $100 and $150 million a year on foodborne illness, and from $470 to over $550 a year on antimicrobial resistance (NIH, 2019). The agency supports about $2.5 billion a year in vaccine development, including malaria, tuberculosis, and AIDS-related vaccines (NIH, 2019). This research has generated considerable knowledge for humanity, much of it intended to improve health in low- and middle-income countries. Regulatory system failures prevent this investment from realizing its full value. If a regulatory authority cannot manage lot releases of a vaccine, for example, these products will fail to reach some intended recipients. The best knowledge about treating or preventing any illness will remain mostly academic without good-quality food and medical products on the market.

The NIH also has some experience in promoting regulatory science. Its Clinical and Translational Science Awards group has a regulatory science subgroup that, in 2014, developed a list of core thematic areas and skills for regulators; it also promoted the consortium model as well suited to a multidisciplinary field (Adamo et al., 2015). The translational science group is also active in a network of medical research institutions around the United States that collaborate on translational research, tools, and processes (NIH, 2018a). Another NIH and FDA partnership produced the Common Fund Regulatory Science Program, “a collaborative effort to accelerate the development and use of new tools, standards, and approaches” to the regulation of medical products (NIH, 2018b). There is also precedent for the NIH’s involvement in Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science. The NIH supports these centers in the United States, working with the FDA and other agencies to create more financial leverage for the programs and for other intramural projects that draw on expertise from a variety of stakeholders (FDA, 2011). The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) also has an interest in promoting operational research and translating that into practice in its partner countries. The agency has some experience with Centers of Excellence already; a recent program in Egypt set up partnerships between Egyptian and U.S. universities in energy, agriculture, and water (USAID, 2019d). The Center of Excellence in Agriculture, for example, is expected to “increase the quality and quantity of applied research projects that transform agricultural business” and to produce the type of research the government can use in policy making (USAID, 2019e). The investment in regulatory science would also be complementary to the agency’s work in food and agriculture, as an implementer of the PEPFAR6 program and the President’s Malaria Initiative and treatment of other infectious diseases (USAID, 2019a,b,c).

___________________

6 Officially, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Research in low- and middle-income countries can be criticized for being “extractive” or characterized by insufficient attention to working with researchers in the host country on local priorities (Chu et al., 2014). The committee envisions that the research priorities for the proposed centers would depend on the local needs. One way to ensure the usefulness of the research produced can be adapted from the WHO’s Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. In this model, policy makers from low- and middle-income countries serve as co-principal investigators, helping to design and conduct studies (Langlois et al., 2017). This strategy helps ensure there is demand for the research produced; it can also improve implementation and scale-up (Langlois et al., 2017). The proposed Centers of Excellence should work in a similar way, involving experts from the regulatory agencies in their target country or region to ensure the research generated targets practical questions of local priority.

It is also important to emphasize that, while the centers may have a training element, they are not training centers. This distinguishes the centers proposed from existing programs, such as the Regional Centers of Regulatory Excellence affiliated with the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (AUDA-NEPAD, n.d.). The main role of these centers is training regulators, at universities and through exchange programs, as well as through practicum with industry, with operational research being a lower priority (AUDA-NEPAD, n.d.). The centers envisioned in this report, in contrast, are primarily operational research centers.

In implementing this recommendation, the agencies might draw valuable lessons on collaborative centers from the Joint Institute for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, a partnership between the University of Maryland and the FDA to increase good-quality research on food safety and human, animal, and plant health (JIFSAN, n.d.-a). Some collaborations, such as one on spice safety in India, have required partnership with the host-country government, as well as with spice farmers and processors and Indian universities (JIFSAN, n.d.-b; Narrod et al., 2018). Local experts run the trainings and act as advocates for the work, mobilizing local funding and developing ways to monitor and evaluate the results of their work (JIFSAN, n.d.-b). Similar work with the Bangladesh Shrimp and Fish Foundation has helped ensure that information about safe aquaculture has reached as large an audience as possible (JIFSAN, n.d.-a). The common thread to both programs is the emphasis on local ownership. In both settings, the training of trainers approach helped improve reach, while tools such as demonstration farms can be used for teaching long after the program ends (Narrod et al., 2018; Spices Board India, 2015).

There are also transferable lessons to be drawn from USAID’s Global Innovation Labs, especially the Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research piece of these labs. Like the centers proposed, the Global

Innovation Labs support scientists in developing countries to conduct research in areas important to the USAID. These partnerships draw on investments from other U.S. government agencies, including the NIH and the USDA (USAID, 2018). For example, the program supported researchers in Tanzania and North Carolina who mapped the geographical distribution of certain viruses that affect cassava, allowing district governments in Tanzania to issue effective quarantines, thereby protecting susceptible crops (USAID, 2018).

Several places in this report highlight research gaps that affect regulators. These may be questions the proposed Centers of Excellence would take on but, to be clear, any center’s research agenda would be tailored to local demand. An initial assessment of needs and scope, involving both funders in the United States and research and policy experts in low- and middle-income countries, would be part of the implementation of this recommendation.

REFERENCES

Abraham, F., and S. L. Schmukler. 2017. Addressing the SME finance problem. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group.

Abuka, C., R. K. Alinda, C. Minoiu, J.-L. Peydró, and A. F. Presbitero. 2019. Monetary policy and bank lending in developing countries: Loan applications, rates, and real effects. Journal of Development Economics 139:185–202.

Adamo, J. E., E. E. Wilhelm, and S. J. Steele. 2015. Advancing a vision for regulatory science training. Clinical and Translational Science 8(5):615–618.

AUDA-NEPAD (African Union Development Agency-New Partnership for Africa’s Development). n.d. Regional centres of regulatory excellence (RCORES). https://www.nepad.org/publication/what-regional-centres-regulatory-excellence-rcores (accessed November 6, 2019).

Avant, S. 2018. Building a one-stop system for food data. https://agresearchmag.ars.usda.gov/2018/mar/food/#printdiv (accessed November 25, 2019).

Barbano, D. B. 2019. ANVISA—Brazil’s national health surveillance agency. Paper read at Committee on Stronger Food and Drug Regulatory Systems Abroad, January 25, 2019, Costa Rica.

Batson, J. S., D. K. Bempong, P. H. Lukulay, N. Ranieri, R. D. Satzger, and L. Verbois. 2016. Assessment of the effectiveness of the CD3+ tool to detect counterfeit and substandard anti-malarials. Malaria Journal 15(1):119.