2

Regulatory Systems, Global Health, and Development

In 1998 the World Health Organization (WHO) first set out a list of essential public health functions, jobs that governments undertake to protect and promote health. These functions have been revisited over the years by different countries and organizations (WHO, 2018a). The various iterations share a common emphasis on health legislation, surveillance, governance, and financing and often on public health regulation and enforcement (WHO, 2018a). Box 2-1 shows one influential iteration of essential public health functions. It should be noted that these essential jobs produce what are described as public goods, meaning that they are both non-excludable (one person’s consumption does not prevent others from consuming it) and non-rival (one person’s consumption does not affect the amount left) (Moon et al., 2017). In general, tax money pays for public goods, making provision of these services difficult when the tax base is small and the needs are great.

Attention to public health and public goods in low- and middle-income countries has been a defining characteristic of the past 20 years, as indicated by the United Nations’ (UN’s) Sustainable Development Goals, and the previous set of international development targets, the Millennium Development Goals (UN, 2015, 2018b). The 2018 World Bank report The Safe Food Imperative pointed out the necessity of food safety for achieving at least seven of the Sustainable Development Goals, especially the goals of ending poverty, ending hunger, and promoting good health (Jaffee et al., 2019). Safe and quality medicines are equally essential for the first three Sustainable Development Goals. Indeed, a functioning regulatory system is related to most of the goals, sometimes indirectly, as a precursor to a

target, or as an outcome of progress in an area. Table 2-1 discusses these relationships.

Although the Sustainable Development Goals, like the Millennium Development Goals before them, emphasize health, they are broader than any one sector. Among the 169 unique targets for the 17 goals, one in particular has commanded an attention eclipsing almost anything else in global health today. Universal health coverage, mentioned as a target under the goal of promoting good health, has been described by Margaret Chan, former director general of the WHO, as “a beacon of hope for a healthier world” and “the most powerful concept that public health has to offer” (Chan, 2015; Chan and Brundtland, 2016; WHO, 2020). Universal coverage was endorsed by the UN General Assembly in 2012 (UN, 2012). Since then, it has been the subject of an ongoing World Bank and World Health Organization collaboration for monitoring (WHO and World Bank, 2015, 2017). Subsequent UN General Assemblies have reaffirmed and supported universal coverage, both as a part of the Sustainable Development Goals and independently; creating, for example, a Universal Health Coverage Day in 2017, and convening a meeting on the topic for heads of state and policy makers in September 2019 (UHC2030, 2019; UN, 2018a). The latter meeting produced a political declaration wherein countries committed to increasing availability of quality, effective medicines, and adequate, healthy food (UN, 2019a). The recent political declaration was also notable for

its mention of “the importance of strengthening regulatory and legislative frameworks” conducive to universal coverage (UN, 2019a).

Part of the appeal of universal coverage as a guiding principle for health is its promise to both improve quality of life and pull people out of poverty. Neglect of preventive services can lead to more serious conditions that are more expensive to treat; unhealthy people are not productive workers, and they have less energy to devote to their families, thereby limiting the potential of the next generation (Frenk and de Ferranti, 2012). Much of the discussion about universal coverage has emphasized the role of catastrophic health expenses in pushing people into poverty (Wagstaff et al., 2018a,b). Policy discussion has been similarly weighted to strategies for pooling funding and improving primary care (Lagomarsino et al., 2012; Moreno-Serra and Smith, 2012; Sachs, 2012). Even the indicators the UN expert working group developed to track progress toward universal coverage, indicators later endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission and the Economic and Social Council, track only measures of health service coverage (e.g., the percentage of health centers screening eligible women for cervical cancer) and financial protection (e.g., the percentage of households reporting catastrophic health expenses) (UHC2030, 2018; UN, 2019b).

Given this context, it is easy to miss the fact that universal coverage, as described in the Sustainable Development Goals, “include[s] financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all” (emphasis added) (UN, 2016). In this definition, quality of medical products is given equal billing with essential services and financial protection, an attention that has not carried over to the policy discussion.

Part of the problem is that monitoring progress depends as much on the likelihood of reliable and straightforward measurement as on construct validity, and measurement has its own challenges (Dunning, 2016). There was much debate on the choice of services used to compute a valid proxy index for access to essential services (Hogan et al., 2018; Schensul, 2016; WHO and World Bank, 2017). Although nobody would deny the role of the regulatory system in reaching universal coverage, the concepts are harder to measure and therefore less amenable to direct, reliable data collection. A recent World Bank report expressed similar reservations regarding the indicators used to measure food safety systems (Jaffee et al., 2019). The 2017 Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines suggested indicators for the performance of regulatory systems including annual publication of risk-based quality surveys, publication of inspection reports, the proportion of manufacturers in a country using international good manufacturing practices, and the presence of a continuously updated agency website (Wirtz et al., 2017).

TABLE 2-1 Relationships Between Regulatory Systems and the Sustainable Development Goals

| SDG | Relevant Targets | Direct or Indirect | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Targets emphasize social protection, access to basic public services and appropriate new technology. | Direct | Safe foods and quality medicines are an essential social protection. Ineffective or unsafe medicines and contaminated food cause illness and disability, which in turn impair children’s capacity to learn, and adults’ ability to work. Access to new technologies is also relevant to this topic; the introduction and control of medical devices and other health technologies are generally in the purview of the drug regulatory agency, though few low- or middle-income countries have regulatory provisions for device safety and performance. |

|

Targets reflect concern with both productivity and market access among small-scale farmers. Other targets call out the role of international cooperation on agricultural research and extension, and the optimal functioning of national and international agriculture markets. | Direct | Food security requires access to safe foods; there is no food secuirty if the food supply is largely unsafe. Market access is related to the ability to meet safety standards, which can pose special challenges for small-scale farmers; cooperation and extension programs can improve productivity and safety, thereby reducing the burden of foodborne disease. |

|

Targets under this goal include universal coverage and reducing deaths from certain causes: maternal, neonatal, and child deaths; deaths from HIV, tuberculosis, or malaria; and premature death from noncommunicable diseases. | Direct | Safe, effective, quality-assured medical products are the cornerstone of a functional health system. Reducing the burden of noncommunicable disease is partly a function of having a safe and wholesome diet. |

|

The quality and availability of higher education are targets, as is ensuring technical, engineering, and scientific skills in the workforce, and the skills that qualify people for employment and running businesses. | Indirect | Jobs in the food and pharmaceutical industries and in food and medicines regulation all require scientific and technical education at the secondary or tertiary level. Deficiencies in technical training were a common gap in the regulatory system, identified in the 2012 report; they persist today. |

|

Targets call out sustainable water use and the problems caused by dumping and hazardous chemicals in the water supply. | Indirect | The suitability of the water supply for agricultural use is a frequent point of collaboration between food and agricultural and environmental agencies. Agricultural use of contaminated water is a common cause of foodborne illness. |

|

Improving economic growth is at the center of this goal. Targets refer to the technological upgrading of industries that create jobs and produce valuable products, bringing more small- and medium-sized producers into the formal economy, and increasing foreign aid for trade. | Direct | Agriculture and medicines formulation are major employers in low- and middle-income countries. For want of investment in these industries, including technological investment, product quality suffers. The regulatory system can make it possible to grow these industries. |

TABLE 2-1 Continued

| SDG | Relevant Targets | Direct or Indirect | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

The first target refers to the regional and international infrastructure that supports economic development and human welfare. Targets mention the ability of small enterprises to participate in the formal economy, increasing scientific research and technical infrastructure in developing countries. | Indirect | Small agricultural producers account for a relatively large market share in low- and middle-income countries, and domestic drug formulation is often done by small and medium-sized businesses. These producers need capital and technical training to meet international standards, new technologies to reduce risk, and a strong testing and distribution infrastructure. A strong regulatory system can encourage competition and innovation, especially when rules are harmonized internationally. |

|

This goal is concerned with, among other things, the use of World Trade Organization agreements to promote development. There are also financial ramifications to Codex standards, making the meaningful participation of developing country representatives in that international forum related to this goal. | Direct | The 2012 report emphasized trade as a tool to raise the floor on food quality in low- and middle-income countries; it also discussed problems with meaningful participation in Codex as a common gap in the food safety system. Inequitable access to quality food and safe medicines impedes social mobility and is a cause of inequality. |

|

A target under this goal calls for a reduction in both deaths and the economic toll of disasters. | Direct | In humanitarian emergencies, access to safe food, vaccines, and medicines reduces loss of life. |

|

Among the targets for responsible consumption are the reduction of food waste all along the supply chain and capacity building among producers in developing countries. | Indirect | The 2012 report discussed the problems of food waste in developing countries, where it is generally between farm and market. Scientific and technical support to producers of food and medical products can help meet responsible production goals. |

|

This goal stresses the development of effective and transparent institutions as well as reduction in corruption and bribery. | Direct | Ensuring quality and safe food and medicines is an essential role of government; the regulatory agency’s responsibility for public health also has economic ramifications, discussed in this report. A predictable, transparent, and functional regulatory agency provides society with public service, promotes fair competition and economic growth, and corrects market asymmetries. |

|

Targets to advance partnerships emphasize the importance of dialogue between the public and private sectors and the need to marshal more money for sustainable development from multiple sources. The role of donor countries to honor development commitments is mentioned, as are building capacity in science and technology, increasing exports, and removing trade barriers in developing countries. | Indirect | The 2012 report suggested trade, particularly the access to lucrative markets in North America, Europe, and Japan, as the incentive needed to raise the floor on product quality in developing countries. While market access is an incentive for some producers, poverty creates markets for inferior products. Enforcement of relevant product safety regulations can improve quality in these markets; greater investment in development can offset the cost of doing so. |

SOURCES: Eze et al., 2019; IOM, 2012; OECD, n.d.; UN, 2018b.

CONTINUING PROGRESS IN HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT

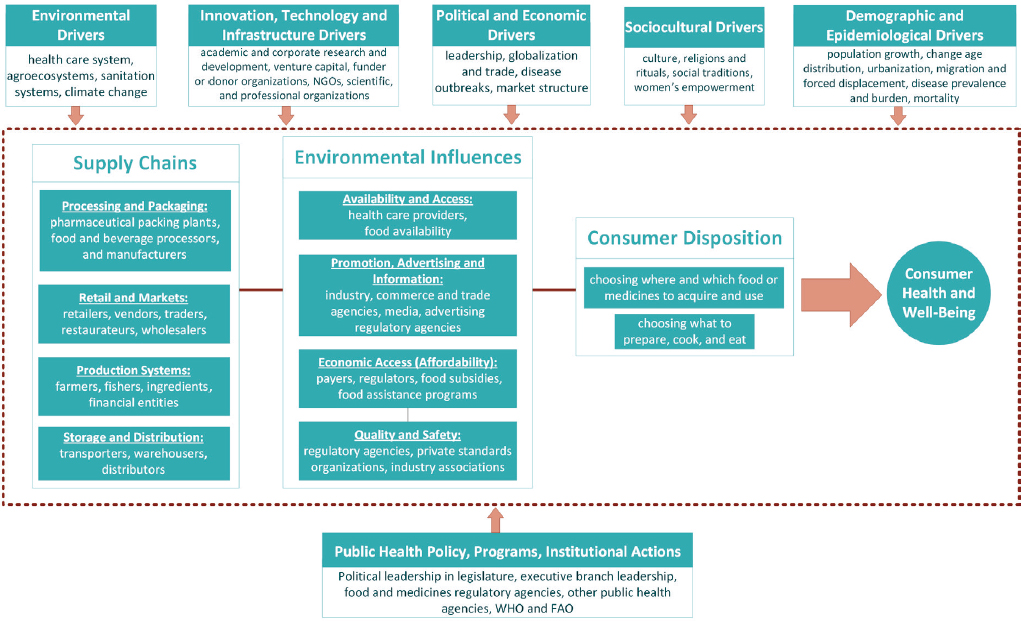

Food and pharmaceutical systems are complicated, but the essential need for safe food and medicines is not. Current trends in global health and development (beyond the Sustainable Development Goals and universal coverage) make attention to the matter of regulatory systems all the more important.

Progress in Health

The last 20 years have seen major health improvement in low- and middle-income countries, with some of the most dramatic gains in children. Between 1990 and 2017, child mortality fell by more than 50 percent, in the least developed countries by over 60 percent (United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, 2018). Neonatal mortality, which accounts for the largest share of child deaths, decreased by half between 1990 and 2017 (Hug et al., 2019). Stunting, a failure to grow reflective of both poor diet and frequent infection in early childhood, is also falling. In an analysis of population surveys from 36 low- and middle-income countries, almost 80 percent found a lower proportion of stunted children in 2012 than in 1990 (Tzioumis et al., 2016).

Similar progress has been made against common infectious diseases. By WHO estimates the treatment for tuberculosis patients averted about 54 million deaths between 2000 and 2017 (WHO, 2018b). The Global Burden of Disease study found HIV and AIDS deaths to be in decline, estimating 19 million years of life saved between 1996 and 2013, 70 percent of them in low- and middle-income countries, a success almost entirely attributable to the HIV medicines donors such as PEPFAR1 and the Global Fund have provided (Murray et al., 2014). Even malaria, a disease that is difficult to treat, especially among pregnant women and young children, the latter accounting for the majority of malaria deaths, has fallen dramatically (Baird, 2013; Cibulskis et al., 2016; Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration, 2016; Murray et al., 2014). By 2016 estimates, 1.2 billion cases of malaria were averted between 2001 and 2015, partly attributable to the use of insecticide-treated nets, residual indoor spraying for mosquitoes, and treatment with artemisinin combination therapy (Cibulskis et al., 2016). Encouraging trends can also be seen in vaccine-preventable diseases. The global program to eradicate polio, after floundering in the early 2000s, made important gains in the early 2010s, culminating in the global eradication of wild poliovirus type 2 in 2015 (Chan, 2017). The following year,

___________________

1 Officially, The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

indigenous measles was eliminated from the Americas (PAHO and WHO, 2016).

Donor organizations, including governments, multilateral organizations, and private philanthropy, deserve a great deal of credit for the health gains of the last 25 years. Maintaining these gains depends heavily on the workforce and infrastructure that support the delivery of health services. A 2014 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report concluded that support for health systems protects donors’ multibillion-dollar investment in programs to fight HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, and can help reduce dependence on foreign aid, which is changing rapidly in both manner and substance (IOM, 2014).

Global Development and Changes in Donor Assistance

Donor aid today may come from more sources than it once did but in smaller amounts, increasing the burden of managing the money in the recipient country (The Economist, 2015, 2016). There are also different strategies for distributing aid, including cash transfers, or payments made directly to the intended beneficiary (in the case of children, to their parents) or to governments for meeting certain targets (The Economist, 2015).

Aid for agriculture has varied over time, increasing sharply in times of global food crisis, as in 2008, and declining during times when other sectors were higher donor priorities (Cohen, 2015). Furthermore, aid to agriculture is often aimed at raising productivity, increasing the profitably of exports, and trade facilitation, making it difficult to disentangle what portion of aid for agriculture or rural development is intended primarily for food safety (ODI, 2012). A recent report on food safety in Africa found that of 518 projects donors funded between 2010 and 2017, the majority were aimed at improving market access for exports to both regional and global markets, with little to no attention given to matters of public health significance to Africans, such as reducing foodborne illness, improving surveillance, consumer education, research on local hazards, or practices in informal markets (GFSP, 2019).

Aid for health, after increasing sharply between 1990 and 2010, has leveled (Dieleman et al., 2016b; Moon and Omole, 2017). The Millennium Development Goals, with their relative emphasis on health, especially child mortality and major infectious diseases, drove much of the early increase in health spending (Dieleman et al., 2016b). As the Sustainable Development Goals, with their longer list of targets, become the motivators for global progress, it is possible that health could lose its relative prominence to donors. Even if it does not, the proportional weight of the donor contribution for health in the recipient countries is changing.

While external assistance makes up about a third of health spending2 in low-income countries, it is far less, between 0.2 and 3.3 percent of health spending, in the middle-income countries that account for three-quarters of the world’s population (Moon and Omole, 2017). The best strategy for foreign aid in middle-income countries, which are often both recipients of assistance and, through the UN system, donors, is debatable (Ottersen et al., 2017). Investments in the institutions that protect and improve health, including the workforce, management, service delivery, monitoring and surveillance, and essential medical products, may be the best use of donor funds in such circumstances (IOM, 2014). Attention to health systems is also seen as a remedy to a historical problem of “excessive emphasis on vertical programs devoted to control specific diseases and … little attention to health systems as a whole” (Frenk et al., 2014).

The burden of disease is also changing in low- and middle-income countries, where malnutrition, infection, and maternal and child deaths are no longer the only, or even the main problems (Frenk et al., 2014). By Global Burden of Disease study estimates, almost three-quarters of all the world’s deaths in 2016 were from noncommunicable diseases (The Lancet, 2017). High blood pressure and smoking are now the leading risk factors for early death and disability around the world (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017). Poor diet, especially one high in sodium or low in whole grains, fruits, and nuts, caused between 10 and 12 million deaths in 2017 alone (Afshin et al., 2019).

Changes in global patterns of disease and disability are in some way a result of a welcome increase in prosperity. In 2015, the percentage of the world population living in extreme poverty3 fell below 10 percent, while the middle class4 grew to over 3 billion (Kharas, 2017; World Bank, n.d.). The world is approaching a historic milestone: Around 2020 the majority of the world’s population will live in a middle-class household (Kharas, 2017). Members of the middle class live longer, eat better, and use more health services than the poor; they are better educated and have more to invest in the education of their children. There is little to no evidence, however, that public services in much of the world are keeping pace with this change (Kharas, 2017).

Safe food and good-quality medical products are a necessary precursor to improved global health and development. No progress could have

___________________

2 This estimate comes from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and does not include spending on food aid, food security, disaster relief, or water sanitation (Dieleman et al., 2016a).

3 Extreme poverty is defined as living on less than $1.90 a day adjusted for purchasing power parity (World Bank, 2015).

4 Defined by a household income between $10 and $100 a day, adjusted for purchasing power parity (Kharas, 2017).

been made against smallpox, for example, without an effective vaccine; well-nourished children are better able to survive infections and succeed in school. A growing demand for diverse foods and medicines is also a consequence of development. Recent projections show global demand for food increasing 74 percent by 2050 (Valin et al., 2014). The market for medical products is also changing. Drugs and vaccines for tropical diseases, for example, were once of little interest to pharmaceutical companies. In 2017, industry spent over $500 million, about 22 percent of total investment in these diseases, on research and product development (Chapman et al., 2018; WHO, 2019a). Research institutes in Brazil, India, Kenya, and Malaysia now develop new treatments for diseases of immense local importance (WHO, 2017).

Enthusiasm for such changes may be tempered by the realization that commensurate improvements in the institutions that guarantee the safety of food, improve the productivity of farmers, oversee the production of medicines, and test the quality of products on the market have not been forthcoming. It is difficult to even say how much donor aid has gone to strengthening regulatory systems, because this is not a category that is explicitly tracked. To understand the importance of the regulatory system to public health, it is necessary to first clarify the responsibilities of regulatory agencies, the conceptual underpinnings of the systems, and the roles of different stakeholders.

UNDERSTANDING THE REGULATORY PROCESS

The regulation of food and medicines is meant to correct a problem known as information asymmetry, a market failure where buyer and seller have unequal information about the products for sale. A carton of milk that has been contaminated looks identical to one treated hygienically; a vial of water and one of vaccine would be indistinguishable to even a sophisticated consumer. Sellers have little interest to correct market failures because such action would not be in any one player’s market interest (Fagotto, 2013; Narrod et al., 2019). When consumers have incomplete information about safety, they cannot effectively choose safe products and reject unsafe ones. As a result, market incentives for safety are weak, requiring government regulatory action to balance the scales.

Box 2-2 lists the essential responsibilities of the regulatory agency as relates to medical products; Box 2-3 lists the same for foods. As these boxes indicate, there are differences in the regulation of foods and medicines. Food producers can usually enter the market without an external assessment of their product’s safety, while market approval for medicines requires industry to demonstrate safety and effectiveness. At the same time, there are

many similarities, especially the shared responsibility for quality assurance, inspection, and enforcement of laws.

There is also a broad conceptual similarity in the regulation of food and medical products. As the 2012 IOM report Ensuring Safe Foods and Medical Products Through Stronger Regulatory Systems Abroad set it out, there are certain attributes that underpin most good regulatory systems (see Box 2-4). The use of science as a basis for policy and the importance of risk as the grounding for regulatory action are central to a good regulatory system (IOM, 2012).

Risk as the Basis for Decisions

Strengthening regulatory systems for both foods and medicines requires a common approach to the scope of work involved. A common framework allows industry, consumers, and other stakeholders to understand where any particular task falls in the regulatory cycle and to see how it relates to other elements of the system. The cornerstone of the regulatory framework, risk can be a difficult concept to convey; it refers to known or suspected threats to health associated with different causes or agents, and risk assessment is the scientific evaluation of such threats (WHO, n.d.-e). For

regulatory agencies the continuous and iterative assessment of the various risks facing a market is essential.

Reducing risks to health in the most cost-effective and efficient way possible is always the goal of regulatory action as resources are scarce and threats are many (IOM and NRC, 2010). While acknowledging that sometimes unforeseen crises arise, in general, risk assessment is a planned part of the agency’s strategy, depending mostly on data and risk analysis (IOM and NRC, 2010). Though expert opinion may be necessary, ideally, risk ranking is the result of numeric weighting in analytical modeling (IOM and NRC, 2010). This is not to say that other considerations do not enter into the process: Risks are considered in light of the whole system, including the cost and feasibility of different responses, as well as factors such as market impacts, public perception, and cost (IOM and NRC, 2010).

Openness and communication with a range of stakeholders are cornerstones of a risk-based system; this includes openness about the uncertainty and variability in the data that support regulations, and the other considerations taken into account when making decisions (IOM and NRC, 2010). Finally, any actions taken and decisions made are eventually evaluated, with the results of the evaluation feeding into the iterative process of choosing priorities and acting on them (IOM and NRC, 2010).

Choosing priorities from among the various risks facing an agency is a complicated process because it balances the likelihood and severity of different types of threats (Kowalcyk, 2019). Box 2-5 sets out the steps of a risk-based process. This framework could aid the discussion among regulators in setting priorities for food and medicine safety. Going through the process of identifying and ranking risks, and assessing ways to mitigate them, will help agencies to understand which interventions can be taken at the country level and which ones are candidates for international collaborative action. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses can clarify the most effective strategies. Relying on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) technical decisions on new chemical entities, for example, allows many agencies to use their drug regulatory staff and budget for urgent local needs, like inspection.

Donor programs also need to acknowledge the process of risk ranking in their projects. It can be tempting as a donor to offer solutions to product safety problems without first evaluating the risks in country and considering the range of possible interventions, their cost, and their suitability to the context. Donors could help promote the risk basis in regulatory action by going through a scientific analysis of risk with their counterparts, and designing their interventions accordingly.

Important Groups and Processes

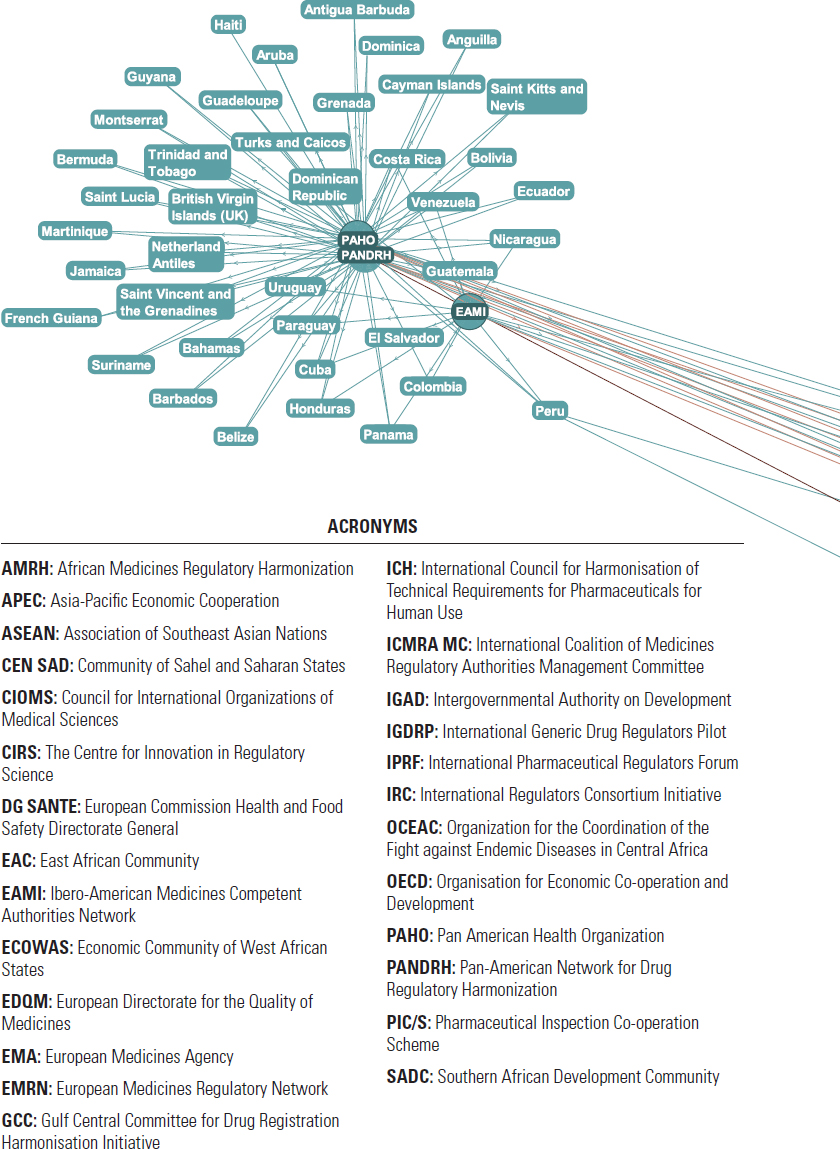

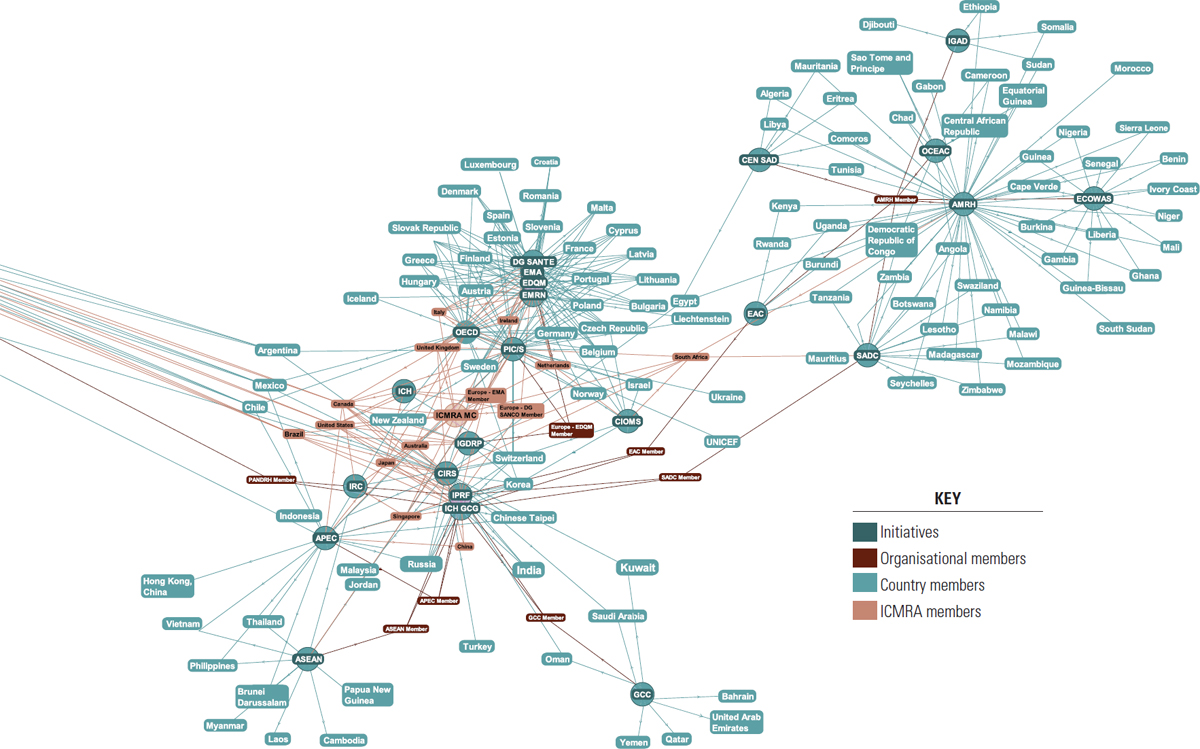

The process of identifying risks and choosing priorities and interventions to counteract them is an iterative process. The process depends, as Box 2-5 makes clear, on data and public consultation. Understanding the nature of such consultation requires an understanding of the main stakeholders regulatory agencies interact with. Figure 2-1 shows relationships among various organizations. Frequent, inclusive interaction with a range of involved parties helps ensure that the regulatory agencies’ priorities reflect the will of society, and that their rules are reasonable and serve the goal of improving access to safe and effective medicines and wholesome foods.

Some parties shown in Figure 2-1 have their own convening power, but more often the onus is on the agency to be open and inclusive with its working groups, scientific meetings, information sessions, and other forums (EFSA, n.d.-b). Such consultation is worth the effort. Over time, the agency’s priorities change, and changing priorities have implications, especially for industry. Regulatory changes may be better accepted when everyone understands the agency’s process and the reasons for its actions. Openness also fosters a respect for the agency’s work. The public cannot value the services regulators provide if they are not aware of them.

Figure 2-1 shows how different parties within a system interact. At the same time, food and medicines are global enterprises, and some important dimensions of the process happen at the global level. One process of particular importance for regulators in low- and middle-income countries is the WHO prequalification of medicines.

WHO Prequalification

Prequalification refers to the assessment, inspection, ongoing re-inspection, and quality control WHO provides for certain essential medical products (WHO, 2013). Vaccine prequalification started in 1987; the medicines program started in 2001 as demand for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria medicines surpassed the production of those manufacturers approved by the FDA and other advanced regulatory authorities (Dellepiane and Wood, 2015; WHO, n.d.-b). In order to give UN agencies and other large procurers a choice of good-quality products for HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis, the WHO provides the equivalent of regulatory assessment for finished medicines, as well as active ingredients and diagnostics; it also maintains 50 labs for quality control (WHO, 2019b, n.d.-b).

Because of prequalification, procurement agencies around the world can be confident they are buying quality-assured medicines, vaccines, diagnostics, and other essential medical products; generic manufacturers have the same safety net in place for their purchase of active ingredients. The

program also has a capacity building element. Regulators from around the world work with WHO staff to review dossiers, evaluate data, and inspect manufacturers together (WHO, 2013). The WHO also provides training and other support to manufacturers and staff at quality control labs (WHO, n.d.-a).

As of early 2019, 546 medicines, the vast majority made in India, have WHO prequalification (WHO, n.d.-c). That designation carries a weight beyond that which licensure from the local regulatory authority would necessarily convey. Although recouping the cost of meeting the international standard can be challenging for some manufacturers, it improves the firms’ standing with international buyers (Huang et al., 2018). Food producers may use certification from independent third parties to a similar end.

Third-Party Certification in Food Safety

Food producers may seek certification of their process by an independent, accredited organization as a way to demonstrate their safety standards, or to verify other features of production, such as animal welfare or worker protections, that might command a price premium or market access (Hatanaka et al., 2005). Such an independent organization, being neither part of government nor part of industry, is often called a “third-party” certifier (Lusk et al., 2011). The certification process will usually involve a preassessment application, as well as review of facilities and operations, and a field audit (Hatanaka et al., 2005).

NOTE: FAO = Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; NGO = nongovernmental organization; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: Adapted from HLPE, 2017.

Like WHO prequalification, third-party certification is a consequence of the need for quality assurance when producers work in multiple countries with widely disparate standards and regulatory capacities (Humphrey, 2008). The larger certification programs put considerable emphasis on harmonization of standards and a common approach to audit, making certification something of a de facto regulatory tool in the global food market (Crandall et al., 2012, 2017). Though the standards set by third-party certifiers do not hold the same legal weight as government regulations, the power of the market can compel implementation (Henson and Humphrey, 2010). Supermarket chains, for example, often require third-party certification from their suppliers (Hatanaka et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2012). Furthermore, governments sometimes adapt and reference third-party certifications in their regulations (Henson and Humphrey, 2010).

On one hand, third-party certification allows farmers in countries with limited food regulatory oversight a chance to access lucrative foreign markets, and many do. Over 100,000 operations in 160 countries are certified through the Global Food Safety Initiative alone (GFSI, 2017). Common standards and protocols help minimize the burden of audits and other compliance measures on producers. Compliance with third-party standards can also encourage upgrades to infrastructure and processes with broad benefits to the market (Henson and Humphrey, 2010).

At the same time, meeting the standards, both for the products and for the hygienic process of production, can be prohibitive for small and medium-sized producers in developing countries, for farmers, and for firms operating further downstream, such as exporters (Humphrey, 2008). A recent analysis of the effects of Global GAP certification (one of the most prominent third-party certifications in agriculture) on exports from low- and middle-income countries was mixed (Fiankor et al., 2017). Though certification can be a boon to some parties, there are factors that influence export competitiveness at levels beyond the farm or processing plant (Fiankor et al., 2017). Reliance on third-party standards, especially if those standards are more exacting than laid out in international agreements, can also undermine the authority of the World Trade Organization to adjudicate trade disputes (Henson and Humphrey, 2010).

Furthermore, while attention to standards with an eye to export markets is understandable and necessary for economic growth, it can distort attitudes toward markets meant for domestic consumers. The estimated $410 billion cumulative donor spending on aid for trade between 2006 and 2017 has brought considerable improvements to agriculture, especially in the least developed countries (OECD and WTO, 2019). Almost 40 percent of aid for trade recipients in low- and middle-income countries, and 61 percent of recipients in the least developed countries, identified agriculture as the sector that has seen the most improvement since 2006 (OECD and

WTO, 2019). Despite such success, there are few if any examples of how to improve the safety of food meant for the domestic market (Grace, 2015). As an evaluation in Kenya explained, investments in aquaculture meant a considerable attention directed to fish for the European market, but that “little effort goes to setting and enforcing domestic-market standards” (Abila, 2003).

International Cooperation

A call to strengthen national regulatory agencies is not contrary to the goal of better international cooperation. International cooperation is an essential part of managing the regulatory workload, especially in small or less developed countries. WHO assessments discussed in the next chapter indicated that about three-quarters of WHO member states lack a functional medicines regulatory system (Khadem, 2018). There are no comparable, holistic estimates of the strength of national food control systems, though assessments of different pieces of the system indicate a similar problem. Only about a quarter of low- and middle-income countries have adequately funded veterinary services, for example (Jaffee et al., 2019). Given the regulatory challenges facing every country, cooperation should improve the strength of the national systems.

Even at a cursory level, the diversity and number of stakeholders in food and medicines systems and the global nature of their work make it necessary to cooperate internationally. Agreement on technical guidelines, requirements for registration, and the approach to inspection help lower the burden of regulatory compliance on industry, which in turn can speed market entry and improve access to quality products. These steps also control the burden on the regulatory agency, reducing repetitive work and making more efficient use of staff time. Such efficiency becomes more important when resources are scarce, and most regulatory agencies have considerable strain on their resources (Distrutti and Ramírez, 2018). Even the FDA, perhaps the best supported regulatory agency in the world, has been described as “chronically under-funded” (IOM, 2007). This is why the ability to participate in regional networks and collaborate with other regulators has been cited as one of the minimum functions of a regulatory authority (Rägo and Santoso, 2008).

Some of the best-known examples of regional regulatory cooperation come from Europe. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is a regional agency for the European Union and the European Economic Area; the European Food Safety Authority serves a similar role for food (EFSA, n.d.a; EMA, 2016b). The EMA works with a network of regulatory authorities on market surveillance, clinical trials, supervision of manufacturers, and market authorization. Under this system, companies seeking market

authorization in Europe can apply for a central authorization for all national markets, multiple authorizations in different countries at the same time, or authorization in one country, with the option to apply for recognition in other European countries (EMA, 2016b). Proposals for similar agencies in Latin America and in Africa are promising but face financial and legal barriers, as well as problems with uneven capacity for enforcement or meeting standards (Distrutti and Ramírez, 2018; Ndomondo-Sigonda et al., 2017). Box 2-6 discusses the proposed African Medicines Agency.

At the same time, there are many useful venues for regulatory harmonization and cooperation separate from a formal agency. Industry has initiated some of these networks; others are the product of trade or bilateral relationships. In an effort to understand the extent of bilateral, regional, and global collaboration programs, the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities undertook a mapping exercise in 2014. The project report clarifies that the network mapped in Figure 2-2 fluctuates as some organizations change their scope or membership and as new ones form. It also comments on considerable overlap among a confusing array of programs, complicated by “similar initiatives” having “differently-worded objectives,” making it difficult to analyze the programs’ effectiveness or identify remaining gaps (EMA, 2016a).

There is no analogous mapping for the food systems, perhaps because there is no comparable international coalition for food regulators. This is not to say that similar collaborations for food safety do not happen. The previous chapter described how national and regional food safety labs work together for foodborne disease surveillance through PulseNet, for example. If anything, the collaborations for food safety are more complicated and fractured as they often involve multiple ministries in a single country (e.g., ministries of agriculture, health, and trade). There is also a veterinary component, since food safety includes the health of food-producing animals. Table 2-2 shows examples of some important global and regional food safety organizations and their mandates.

The WHO and the FAO are clear leaders in matters of global health and food safety. The two organizations jointly convene the Codex Alimentarius Commission, the international food standards and guidelines meant to protect health and facilitate trade (FAO, n.d.-a). The agencies also respond to members’ requests for food safety support, as in 2000 when concerns raised at the World Health Assembly led the WHO and the FAO to develop the International Food Safety Authorities Network, called INFOSAN (WHO and FAO, 2011). INFOSAN aims to build food safety networks within and among countries thereby improving outbreak response and facilitating recalls when necessary (see Box 2-7). Participating countries (including, at last count, 97 percent of WHO member states) designate at least one contact for emergency response; they also commit to taking part in various food safety activities with other members (Savelli et al., 2019). While these activities may benefit all parties, recent analysis suggests that the countries with good food safety systems to start with are the most active participants (Savelli et al., 2019). The authors, food safety experts from the WHO and a British university, also commented on, “an abundance of regional [food safety] networks and initiatives at various stages of development and utility” and called for a mapping of the networks and the relationships among them (Savelli et al., 2019).

Modern food production is so complex, and supply chains so vast, that even the people with the best knowledge of the system see only pieces of it. The lack of global mapping of food safety stakeholders is itself unfortunate; it is also symptomatic of a larger problem. Food regulators do not have a standing venue to interact with their counterparts in other countries. In this vacuum, it is not clear that any of the multiple regional cooperative ventures or various well-established technical groups are working to maximum efficiency or avoiding redundant effort.

Convening food regulators in regular meetings is also an investment in emergency response. Without a regular opportunity to come together, communication among regulators during a crisis will be at best ad hoc, reinforcing existing relationships. During the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, for example, the newly formed International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities committed to cooperation among agencies and with the WHO to speed the review of investigation medicines and vaccines for Ebola (ICMRA, 2014; WHO, 2015). In an international crisis affecting the food supply, valuable response time could be wasted identifying responsible parties in different ministries.

Recommendation 2-1: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization should convene biennial meetings for food safety regulators similar to the International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities.

As the UN agencies responsible for global public health and food security, the WHO and the FAO are the best choices to convene the food regulatory meetings suggested. This would be consistent with the agencies’ missions to promote health and nutrition and to support governments on matters related to their health and food systems (FAO, n.d.-d; WHO, n.d.-f, n.d.-g). Together the FAO and the WHO convene the Codex Alimentarius Commission and INFOSAN, as well as an expert working group on food additives (FAO, n.d.-a, n.d.-b; WHO, n.d.-d). Convening food regulators is also consistent with previous statements from both organizations on the value of regulatory collaboration (FAO, n.d.-c; ICDRA, 2018; WHO, 2015). The organizations also have existing relationships with ministries that would be asked to designate participants for this activity.

The committee chose the International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities (ICDRA) as a model for this recommendation but has no desire to be overly prescriptive in doing so. The WHO first convened ICDRA in 1980 to foster consensus building on drug regulatory questions (FAO, n.d.-c). Now the meetings generally have a few days of programming open to any registered participant, as well as several days of sessions for regulators only (FAO, n.d.-c). ICDRA involves regulators from many levels

This page intentionally left blank.

of government, technical staff as well as agency leaders. The International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities, in contrast, involves only heads of agencies and other senior leaders; it is a newer collaboration, and one convened by the leaders themselves (WHO, 2015). Both types of meetings have value. The heads of agencies can best comment on their organizations’ strategic direction; they can also direct relatively quick cooperation when necessary. At the same time, there is value to convening technical experts and people at different levels of the agency, who also benefit from the technical discussion and networking (WHO, 2015). For this reason, ICDRA is a good model, and because self-convening may be less realistic for food regulators. There are often multiple government officials of equal rank overseeing food safety, making diffusion of responsibility for convening them more likely.

Regular meetings give various food safety experts the chance to have a predictable and ongoing discussion about current issues. There may be greater political will to support this international discussion now than there has been in the past, driven in part by the estimates of disease burden and cost of foodborne illness discussed in the previous chapter. An inclusive, international discussion on food safety is one way to take advantage of the current interest in the topic.

The increasing scientific and legal complexity of regulatory work and the interconnected nature of the food supply chain make it necessary for food regulators to have a standing, formal venue for technical exchange and cooperation. This forum would be to the benefit of all parties, especially regulators from small countries who may have limited occasions to build relationships with their counterparts abroad.

The programs shown in Table 2-2 and others like them reflect international response to various food safety problems, some existing for a century or more, others only a few years old. These programs and other, sometimes impromptu, collaborations among food regulators have great value, but an inclusive global convening at regular intervals would help ensure they operate to their maximum effectiveness.

Technical experts and scientists today are often criticized for inadequate sharing of information, for working in so-called silos (Lowrey, 2014; Satell, 2017; Talsma, 2016). Some of this perceived narrowness of focus is a consequence of the complexity of their fields and the amount of knowledge generated. In international work, language and distance can magnify the challenge; there are only so many professional connections anyone can be expected to maintain. This is why the convening power of the WHO and the FAO would be a powerful force for collaboration, and one that is needed for food regulators.

TABLE 2-2 A Cross-Section of Multinational Food Safety Programs

| Region or Countries | Role | Website | |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Organizations | |||

| Joint FAO and WHO Food Standards Program | Global | Building capacity to prevent, detect, and manage foodborne risks; promoting safe food handling | http://www.fao.org/food-safety/en https://www.who.int/health-topics/food-safety |

| Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture; Agricultural Health, Safety, and Food Quality Program | The Americas | Promoting productive, competitive, and sustainable agriculture through local, regional, and global markets | https://iica.int/en/programs/agricultural-health |

| Pan America Health Organization Food Safety Regional Program | The Americas | Strengthening national food safety and surveillance systems, risk-based inspection and control systems, and laboratories | https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15241:food-safety-is-everyone-s-business&Itemid=1926&lang=en |

| Caribbean Agricultural Health and Food Safety Agency | Caribbean countries | Supporting national agricultural health and food safety systems in accordance with the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Agreement | https://caricom.org/about-caricom/who-we-are/institutions1/caribbean-agricultural-health-and-food-safety-agency-cahfsa |

| International Standard Setting Bodies | |||

| Codex Alimentarius Commission | Global | Protecting human health from food safety hazards and facilitating trade | http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/en |

| World Animal Health Organization | Global | Improving animal health and facilitating trade | http://www.oie.int |

| International Plant Protection Convention | Global | Improving plant health and facilitating trade | https://www.ippc.int/en |

| National Regulatory Units | |||

| European Food Safety Authority | European Union member states | Supporting members’ food safety agencies and European Commission institutions with scientific advice and communication on food safety risks | http://www.efsa.europa.eu |

| Regional Industry Organization | |||

| Food Safety Asia | Various Asia and Middle East | Harmonizing laboratory practices, establishing a regional laboratory network | http://www.foodsafetyasia.net |

| International Food Safety Capacity Building Organizations or Networks | |||

| World Trade Organization Standard and Trade Development Facility | Global | Improving market access in low- and middle-income countries with attention to sanitary and phytosanitary problems | https://www.standardsfacility.org |

| Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation; Food Safety Cooperation Forum; Partnership Training Institute Network | APEC countries | Engaging industry and academic food safety experts with regulators for capacity building in food safety | http://fscf-ptin.apec.org |

| Food Safety Risk Analysis Consortium | Latin America and the Caribbean | Developing and integrating risk analysis in the Americas | https://www.paho.org/panaftosa/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1771:food-safety-risk-analysis-consortium-fsrisk&Itemid=0 |

| JIFSAN | Global | Research to improve food safety and capacity building | https://jifsan.umd.edu |

TABLE 2-2 Continued

| Region or Countries | Role | Website | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third-Party Auditors | |||

| Global GAP | Global | Quality and safety standards of good agricultural practices tailored to primary agricultural production | https://www.globalgap.org/uk_en |

| Global Aquaculture Alliance Seafood | Global | Promote responsible aquaculture practices through education, advocacy, and demonstration | https://www.aquaculturealliance.org |

| Primus GFS | Global | Auditing of Good Agricultural Practices and Good Manufacturing Practices, as well as Food Safety Management Systems | http://www.primusgfs.com |

| Monitoring and Data-Sharing Efforts | |||

| Emergency Prevention System for Food Safety | Global | Facilitating rapid sharing of information during food safety emergencies through the International Food Safety Authorities Network | http://www.fao.org/food/food-safety-quality/empres-food-safety/en |

| International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN) | Global | Collaborating among food safety authorities for crisis mitigation | https://www.who.int/activities/responding-to-food-safety-emergencies-infosan |

| PulseNet International | ~86 countries worldwide | Public health and food safety laboratory network | http://www.pulsenetinternational.org/international |

| Research or Trade Associations | |||

| International Association for Food Protection | Individual members from more than 50 countries | Professional association for people working in any aspect of food safety (farming, processing, distribution, etc.) | https://www.foodprotection.org/about |

| Global Food Safety Initiative | Global | Food industry collaboration to reduce food safety risks and improve efficiency | https://www.mygfsi.com/about-us/about-gfsi/what-is-gfsi.html |

| Scientific Guidance | |||

| International Commission on Microbiological Specifications of Food | Global | Providing scientific guidance to governments and industry on the microbiological safety of foods | http://www.icmsf.org |

| HACCP Alliance Capacity Building Activities | |||

| International HACCP Alliance | Meat focused USDA FSIS requirements | Providing a uniform program to assure safer meat and poultry products; hosted by Texas A&M University | http://www.haccpalliance.org/sub/index.html |

| Seafood HACCP Alliance* | Global | Training program involving representation from FDA, USDA, U.S. Department of Commerce | http://www.afdo.org/page-1186198 |

| Food Safety Preventive Controls Alliance* | U.S. requirement for market access with global implications | Assisting companies producing human and animal food in complying with the U.S. preventive control regulations | https://www.ifsh.iit.edu/fspca |

| Produce Safety Alliance* | U.S. requirement for market access with global implications | Training and outreach to assist producers and companies with produce safety, public–private partnership hosted by Cornell University | https://producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/food-safety-modernization-act/produce-safety-rule |

| Produce Safety Rule-Produce International Partnership* | U.S. requirement for market access with global implications | Building capacity for the produce safety rule internationally | https://jifsan.umd.edu/training/international/courses/pip/description |

TABLE 2-2 Continued

| Region or Countries | Role | Website | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprout Safety Alliance* | U.S. requirement for market access with global implications | Training sprouts producers to enhance understanding and implementation of best practices for improving sprouts safety | https://www.ifsh.iit.edu/ssa |

| Private Sector Initiatives | |||

| SSAFE | Food companies | Promoting public–private partnerships for food safety and standards | http://www.ssafe-food.org/about-ssafe |

| Food Industry Asia | Food companies in Asia | Enhancing the industry’s role as a partner in the development of scientific food policy in the region | https://foodindustry.asia/home |

| Regional Networks (including Public and Private Sector) | |||

| African Food Safety Network | Africa Union member states | Collaborating among food safety stakeholders in Africa for public health and trade | https://www.africanfoodsafetynetwork.org |

| ASEAN Food Safety Network | Southeast Asia | Exchanging information among ASEAN member states | https://www.aseanfoodsafetynetwork.net |

* Affiliated with Association of Food and Drug Officials.

REFERENCES

Abila, R. O. 2003. Food safety in food security and food trade—case study: Kenyan fish exports. 2020 Vision Focus 10.

African Union. 2019a. List of countries which have signed, ratified/acceded to the treaty for the establishment of the African Medicines Agency. https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36892-sl-TREATY%20FOR%20THE%20ESTABLISHMENT%20OF%20THE%20AFRICAN%20MEDICINES%20AGENCY.pdf (accessed August 5, 2019).

African Union. 2019b. The republic of Madagascar signed the treaty for the establishment of the African Medicine Agency (AMA), edited by M. Agama-Anyetei. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union.

Afshin, A., P. J. Sur, K. A. Fay, L. Cornaby, G. Ferrara, J. S. Salama, E. C. Mullany, K. H. Abate, C. Abbafati, Z. Abebe, M. Afarideh, et al. 2019. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet 393(10184):1958–1972.

Allam, M., N. Tau, S. L. Smouse, P. S. Mtshali, F. Mnyameni, Z. T. H. Khumalo, A. Ismail, N. Govender, J. Thomas, and A. M. Smith. 2018. Whole-genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes sequence type 6 isolates associated with a large foodborne outbreak in South Africa, 2017 to 2018. Genome Announcement 6(25).

Baird, J. K. 2013. Malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax: Recurrent, difficult to treat, disabling, and threatening to life—the infectious bite preempts these hazards. Pathogens and Global Health 107(8):475–479.

Chan, M. 2015. Universal health coverage: A pro-poor pillar of sustainable development. Paper presented at International Conference on Universal Health Coverage in the New Development Era, Tokyo, Japan.

Chan, M. 2017. The power of vaccines: Still not fully utilized. In Ten years in public health, 2007–2017. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Chan, M., and G. H. Brundtland. 2016. Universal health coverage: An affordable goal for all. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/commentaries/2016/universal-health-coverage/en (accessed May 15, 2019).

Chapman, N., A. Doubell, L. Oversteegen, P. Barnsley, V. Chowdhary, G. Rugarabamu, M. Ong, and J. Borri. 2018. Neglected disease research and development: Reaching new heights. G-FINDER Report.

Cibulskis, R. E., P. Alonso, J. Aponte, M. Aregawi, A. Barrette, L. Bergeron, C. A. Fergus, T. Knox, M. Lynch, E. Patouillard, S. Schwarte, S. Stewart, and R. Williams. 2016. Malaria: Global progress 2000–2015 and future challenges. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 5(1):61.

Cohen, M. J. 2015. U.S. aid to agriculture: Shifting focus from production to sustainable food security. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 3(2).

Crandall, P., E. J. Van Loo, C. A. O’Bryan, A. Mauromoustakos, F. Yiannas, N. Dyenson, and I. Berdnik. 2012. Companies’ opinions and acceptance of global food safety initiative benchmarks after implementation. Journal of Food Protection 75(9):1660–1672.

Crandall, P. G., A. Mauromoustakos, C. A. O’Bryan, K. C. Thompson, F. Yiannas, K. Bridges, and C. Francois. 2017. Impact of the global food safety initiative on food safety worldwide: Statistical analysis of a survey of international food processors. Journal of Food Protection 80(10):1613–1622.

Dellepiane, N., and D. Wood. 2015. Twenty-five years of the WHO vaccines prequalification programme (1987–2012): Lessons learned and future perspectives. Vaccine 33(1):52–61.

Dieleman, J., C. J. L. Murray, K. C. Margot, M. Campbell, A. Chapin, E. Eldrenkamp, T. Matyasz, A. Micah, A. Reynolds, N. Sadat, M. Schneider, and R. Sorensen. 2016a. Methods annex. In Financing global health 2016: Development assistance, public and private health spending for the pursuit of universal health coverage, edited by IHME. Seattle, WA.

Dieleman, J. L., M. T. Schneider, A. Haakenstad, L. Singh, N. Sadat, M. Birger, A. Reynolds, T. Templin, H. Hamavid, A. Chapin, and C. J. Murray. 2016b. Development assistance for health: Past trends, associations, and the future of international financial flows for health. The Lancet 387(10037):2536–2544.

Distrutti, M., and I. Ramírez. 2018. Would a regional regulatory agency for health technologies be feasible? In Gente Saludable. IDP.

Dunning, C. 2016. 230 indicators approved for SDG agenda. In Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/230-indicators-approved-sdg-agenda (accessed December 7, 2019).

EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). n.d.-a. How we work. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/about/howwework (accessed October 4, 2019).

EFSA. n.d.-b. Stakeholder engagement. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/partnersnetworks/stake-holder (accessed July 16, 2019).

EMA (European Medicines Agency). 2016a. Connecting the dots towards global knowledge of the international medicine regulatory landscape: Mapping of international initiatives.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/connecting-dots-towards-global-knowledge-international-medicine-regulatory-landscape-mapping_en.pdf (accessed September 5, 2019).

EMA. 2016b. The European regulatory system for medicines: A consistent approach to medicines regulation across the European Union. London, UK: European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/european-regulatory-system-medicines-european-medicines-agency-consistent-approach-medicines_en.pdf (accessed September 11, 2019).

Eze, S., W. Ijomah, and T. C. Wong. 2019. Accessing medical equipment in developing countries through remanufacturing. Journal of Remanufacturing 9(3):207–233.

Fagotto, E. 2013. Private roles in food safety provision: The law and economics of private food safety. European Journal of Law and Economics 32.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2003. Elements of a national food control system. http://www.fao.org/3/y8705e/y8705e04.htm (accessed May 24, 2019).

FAO. n.d.-a. About Codex Alimentarius. http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/about-codex/en (accessed July 16, 2019).

FAO. n.d.-b. Chemical risks and JECFA. http://www.fao.org/food/food-safety-quality/scientific-advice/jecfa/en (accessed July 15, 2019).

FAO. n.d.-c. Collaboration between countries. http://www.fao.org/ag/againfo/programmes/en/empres/gemp/empres/emp3/3510-countries.html (accessed July 16, 2019).

FAO. n.d.-d. What we do. http://www.fao.org/about/what-we-do/en (accessed July 15, 2019).

Fiankor, D., I. Flachsbarth, A. Masood, and B. Brummer. 2017. Does GlobalGAP certification promote agricultural exports? Paper presented at 19th Annual European Study Group Conference, July 27, Florence, Italy.

Frenk, J., and D. de Ferranti. 2012. Universal health coverage: Good health, good economics. The Lancet 380(9845):862–864.

Frenk, J., O. Gomez-Dantes, and S. Moon. 2014. From sovereignty to solidarity: A renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. The Lancet 383(9911):94–97.

GFSI (Global Food Safety Initiative). 2017. GFSI on strategic partnerships to enhance the safety of imported foods. https://mygfsi.com/2017/02/21/gfsi-on-strategic-partnerships-to-enhance-the-safety-of-imported-fods (accessed February 13, 2020).

GFSP (Global Food Safety Partnership). 2019. Food safety in Africa: Past endeavors and future directions. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration. 2016. Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: Findings from the global burden of disease 2013 study. JAMA Pediatrics 170(3):267–287.

Grace, D. 2015. Food safety in low and middle income countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12(9):10490–10507.

Hatanaka, M., C. Bain, and L. Busch. 2005. Third-party certification in the global agrifood system. Food Policy 30(3):354–369.

Henson, S., and J. Humphrey. 2010. Understanding the complexities of private standards in global agri-food chains as they impact developing countries. The Journal of Development Studies 46(9):1628–1646.

HLPE (High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2017. Nutrition and food systems: A report by high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Hogan, D. R., G. A. Stevens, A. R. Hosseinpoor, and T. Boerma. 2018. Monitoring universal health coverage within the sustainable development goals: Development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. The Lancet Global Health 6(2):e152–e168.

Huang, Y., K. Pan, D. Peng, and A. Stergachis. 2018. A qualitative assessment of the challenges of WHO prequalification for anti-malarial drugs in China. Malaria Journal 17(1):149.

Hug, L., M. Alexander, D. You, and L. Alkema. 2019. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: A systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health 7(6):e710–e720.

Humphrey, J. 2008. Private standards, small farmers and donor policy: EUREPGAP in Kenya,. London, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

ICDRA (International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities). 2018. Smart safety surveillance: A life-cycle approach to promoting safety of medical products. Paper read at 18th International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities, Dublin, Ireland.

ICMRA (International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities). 2014. Consolidated joint ICMRA statement Ebola.http://www.icmra.info/docs/Consolidated_Joint_ICMRA_statement_Ebola.pdf (accessed February 19, 2020).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2017. Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. Seattle, WA: IHME.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2007. Challenges for the FDA: The future of drug safety: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2012. Ensuring safe foods and medical products through stronger regulatory systems abroad. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Investing in global health systems: Sustaining gains, transforming lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC (National Research Council). 2010. Enhancing food safety: The role of the Food and Drug Administration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jaffee, S., S. Henson, L. Unnevehr, D. Grace, and E. Cassou. 2019. The safe food imperative : Accelerating progress in low- and middle-income countries. Agriculture and food series. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Khadem, A. 2018. Building regulatory capacity in countries to improve the regulation of health products. https://www.who.int/medicines/technical_briefing/tbs/TBS2018_RSS_Capacity_Building_CRSgroup.pdf?ua=1 (accessed February 13, 2020).

Kharas, H. 2017. The unprecedented expansion of the global middle class: An update. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Kowalcyk, B. 2019. Developing a risk-based framework for food safety decision-making in low and middle income countries. Paper presented at Stronger Food and Drug Regulatory Systems Abroad, April 3, Washington, DC.

Lagomarsino, G., A. Garabrant, A. Adyas, R. Muga, and N. Otoo. 2012. Moving towards universal health coverage: Health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in africa and asia. The Lancet 380(9845):933–943.

Lee, J., G. Gereffi, and J. Beauvais. 2012. Global value chains and agrifood standards: Challenges and possibilities for smallholders in developing countries. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(31):12326–12331.

Lowrey, A. 2014. World Bank revamping is rattling employees. The New York Times, May 27, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/28/business/international/world-bank-revamping-is-rattling-employees.html?login=smartlock&auth=login-smartlock (accessed February 13, 2020).

Lusk, J. L., J. Roosen, J. F. Shogren, J. A. Caswell, and S. M. Anders. 2011. Private versus third party versus government labeling. In The Oxford handbook of the economics of food consumption and policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moon, S., and O. Omole. 2017. Development assistance for health: Critiques, proposals and prospects for change. Health Economics, Policy, and Law 12(2):207–221.

Moon, S., J. A. Rottingen, and J. Frenk. 2017. Global public goods for health: Weaknesses and opportunities in the global health system. Health Economics, Policy, and Law 12(2):195–205.

Moreno-Serra, R., and P. C. Smith. 2012. Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? The Lancet 380(9845):917–923.

Murano, E. 2018. Listeria in South Africa: Lessons learned. In Food Safety Net Services. http://fsns.com/news/listeria-in-south-africa (accessed December 7, 2019)

Murray, C. J., K. F. Ortblad, C. Guinovart, S. S. Lim, T. M. Wolock, D. A. Roberts, E. A. Dansereau, N. Graetz, R. M. Barber, J. C. Brown, H. Wang, H. C. Duber, et al. 2014. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. The Lancet 384(9947):1005–1070.

Narrod, C., A. Stumpf, and X. Dou. 2019 (unpublished). Harnessing public–private partnerships for data sharing to measure the impact of food safety capacity building.

National Institute for Communicable Diseases. 2018. Listeriosis update. http://www.nicd.ac.za/listeriosis_update (accessed June 26, 2019).

Ndomondo-Sigonda, M., J. Miot, S. Naidoo, A. Dodoo, and E. Kaale. 2017. Medicines regulation in Africa: Current state and opportunities. Society of Pharmaceutical Medicine 31(6):383–397.

Ndomondo-Sigonda, M., M. Agama-Anyetei, G. Mahlangu, and H. Mkandawire. 2018. African Medicines Agency Establishment Treaty adopted by African ministers of health. Global Forum 10(7).

NEPAD (New Partnership for Africa’s Development). 2019. AUDA-NEPAD and WHO, joint secretariat of the African Medicines Regulatory Harmonisation initiative. http://www.nepad.org/news/auda-nepad-and-who-joint-secretariat-african-medicines-regulatory-harmonisation (accessed July 15, 2019).

ODI (Overseas Development Institute). 2012. Measuring aid to agriculture and food security.https://www.odi.org/publications/6328-aid-agriculture-food-security-measurement (accessed December 7, 2019).

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). n.d. Regulatory reform and innovation. https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/2102514.pdf (accessed November 18, 2019).

OECD and WTO (World Trade Organization). 2019. Aid for trade facts and figures. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/aid4trade19_facts_e.pdf (accessed September 30, 2019).

Ottersen, T., S. Moon, and J. A. Rottingen. 2017. The challenge of middle-income countries to development assistance for health: Recipients, funders, both or neither? Health Economics, Policy, and Law 12(2):265–284.

PAHO (Pan American Health Organization). 2002. Public health in the Americas: Conceptual renewal, performance assessment, and bases for action. Washington, DC: PAHO.

PAHO and WHO (World Health Organization). 2016. Region of the Americas is declared free of measles. https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=12528:region-americas-declared-free-measles&Itemid=1926&lang=en (accessed November 25, 2019).

Rägo, L., and B. Santoso. 2008. Drug regulation: History, present and future. In Drug benefits and risks: International textbook of clinical pharmacology, revised 2nd edition, edited by C. J. van Boxtel, B. Santoso, and I. R. Edwards. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press.

Sachs, J. D. 2012. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. The Lancet 380(9845):944–947.

Salama, P. J., P. K. B. Embarek, J. Bagaria, and I. S. Fall. 2018. Learning from Listeria: Safer food for all. The Lancet 391(10137):2305–2306.

Satell, G. 2017. Breaking down silos is a myth, do this instead: Horizontal connections are what’s important. https://www.inc.com/greg-satell/breaking-down-silos-is-a-myth-do-this-instead.html (accessed July 15, 2019).

Savelli, C. J., A. Bradshaw, P. Ben Embarek, and C. Mateus. 2019. The FAO/WHO international food safety authorities network in review, 2004–2018: Learning from the past and looking to the future. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease 16(7):480–488.

Schensul, D. 2016. SDG 3: Target 3.8: Indicator 3.8.1 definitions, metadata, trends, work plan, and challenges. Paper presented at Regional Meeting: Enhancing capacity for the integration of the ICPD agenda into SDG adaptation and review processes in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, November 2–4, Geneva, Switzerland.

Talsma, T. 2016. Eliminating silos in regionally distributed organizations to encourage knowledge sharing. Senior project paper 8. Allendale, MI: Grand Valley State University.

The Economist. 2015. It’s not what you spend; how to make aid to poor countries work better. https://www.economist.com/international/2015/05/23/its-not-what-you-spend (accessed May 24, 2019).

The Economist. 2016. Misplaced charity: Aid is best spent in poor, well-governed countries. That isn’t where it goes. https://www.economist.com/international/2016/06/11/misplaced-charity (accessed May 24, 2019).

The Lancet. 2017. Life, death, and disability in 2016. The Lancet 390(10100):1083.

Thomas, D. 2019. African pharma: A prescription for success. https://africanbusinessmagazine.com/sectors/health-sectors/african-pharma-a-prescription-for-success (accessed June 25, 2019).

Tzioumis, E., M. C. Kay, M. E. Bentley, and L. S. Adair. 2016. Prevalence and trends in the childhood dual burden of malnutrition in low- and middle-income countries, 1990–2012. Public Health and Nutrition 19(8):1375–1388.

UHC2030 (Universal Health Coverage). 2018. SDG indicator 3.8.1: Measure what matters. https://www.uhc2030.org/news-events/uhc2030-news/sdg-indicator-3-8-1-measure-what-matters-465653 (accessed May 16, 2019).

UHC2030. 2019. The UN high-level meeting (UN HLM) on universal health coverage, 23 September 2019, New York. https://www.uhc2030.org/un-hlm-2019 (accessed May 15, 2019).

UN (United Nations). 2012. 67/l.36 Global health and foreign policy. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/67/L.36 (accessed May 15, 2019).

UN. 2015. Millennium development goals. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals (accessed May 15, 2019).

UN. 2016. Final list of proposed sustainable development goal indicators. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11803Official-List-of-Proposed-SDG-Indicators.pdf (accessed May 16, 2019).

UN. 2018a. International Universal Health Coverage Day 12 December. https://www.un.org/en/events/universal-health-coverage (accessed May 15, 2019).

UN. 2018b. Sustainable development goals. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed May 15, 2019).

UN. 2019a. Political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage “universal health coverage: Moving together to build a healthier world.”https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/05/UHC-Political-Declaration-zero-draft.pdf (accessed May 15, 2019).

UN. 2019b. SDG indicators: Metadata repository. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata (accessed May 16, 2019).

United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. 2018. Levels & trends in child mortality: Report 2018, estimates developed by the un inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

Valin, H., R. D. Sands, D. van der Mensbrugghe, G. C. Nelson, H. Ahammad, E. Blanc, B. Bodirsky, S. Fujimori, T. Hasegawa, P. Havlik, E. Heyhoe, P. Kyle, D. Mason-D’Croz, S. Paltsev, S. Rolinski, A. Tabeau, H. van Meijl, M. von Lampe, and D. Willenbockel. 2014. The future of food demand: Understanding differences in global economic models. Agricultural Economics 45(1):51–67.

Wagstaff, A., G. Flores, J. Hsu, M. F. Smitz, K. Chepynoga, L. R. Buisman, K. van Wilgenburg, and P. Eozenou. 2018a. Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health 6(2):e169–e179.

Wagstaff, A., G. Flores, M. F. Smitz, J. Hsu, K. Chepynoga, and P. Eozenou. 2018b. Progress on impoverishing health spending in 122 countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health 6(2):e180–e192.

Whitworth, J. 2018. South Africa declares end to largest ever Listeria outbreak. https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2018/09/south-africa-declares-end-to-largest-ever-listeria-outbreak (accessed June 24, 2019).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2003. Effective medicines regulation: Ensuring safety, efficacy and quality. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2013. Prequalification of medicines by WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/prequalification-of-medicines-by-who (accessed June 19, 2019).

WHO. 2014. WHO support for medicines regulatory harmonization in africa: Focus on East African community. WHO Drug Information 28(1):11–15. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2015. Regulatory collaboration, the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA). WHO Drug Information 29(1):3–6. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2017. Integrating neglected tropical diseases into global health and development: Fourth WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2018a. Essential public health functions, health systems and health security: Developing conceptual clarity and a WHO roadmap for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2018b. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2019a. Distribution of R&D funding flows for neglected diseases (g-finder), by source and type of funding. https://www.who.int/research-observatory/monitoring/inputs/neglected_diseases_source/en (accessed May 28, 2019).

WHO. 2019b. WHO list of prequalified quality control laboratories: 47th editon. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/sites/default/files/documents/PQ_QCLabsList_27.pdf (accessed October 2, 2019).

WHO. 2020. Universal health coverage day. https://www.who.int/life-course/news/events/uhc-day/en (accessed January 16, 2020).

WHO. n.d.-a. Capacity building. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/content/capacity-building-0 (accessed July 16, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-b. Key facts about the WHO prequalification project. https://www.who.int/3by5/prequal/en (accessed July 16, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-c. Medicines/finished pharmaceutical products. https://extranet.who.int/prequal/content/prequalified-lists/medicines (accessed February 13, 2020).

WHO. n.d.-d. Responding to food safety emergencies (INFOSAN). https://www.who.int/activities/responding-to-food-safety-emergencies-infosan (accessed July 15, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-e. Risk assessment. https://www.who.int/foodsafety/micro/riskassessment/en (accessed May 29, 2019).

WHO. n.d.-f. What we do. https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do (accessed July 15, 2019).