1

Introduction

TMD has affected every aspect of my life: physically, emotionally, financially, psychologically, professionally, and it has affected my relationships, my passions, my independence, and at times my dignity. It cut me off at the knees and changed the landscape of my life, and what I imagined my life would be. I have had to accept that, we’ve all had no choice but to accept that.

—Adriana V.

Consider the joints of the human body. What might first come to mind are the hips and knees—the large joints that support us in our mobility—followed by the wrists, ankles, elbows, fingers, and toes—the smaller joints that support nearly everything else. What can be overlooked, although clearly evident in the mirror, is one of the most used, most necessary, and perhaps most misunderstood set of joints—those of the jaw—which are critical to the vital work of human life, including eating, talking, kissing, and even breathing.

This report focuses on temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), a set of more than 30 health disorders associated with both the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and the muscles and tissues of the jaw. TMDs have a range of causes and often co-occur with a number of overlapping medical conditions, including headaches, fibromyalgia, back pain, and irritable bowel syndrome. Both the range of causes and the overlapping conditions contribute to widespread misunderstandings regarding the importance and function of the jaw joints. TMDs can be transient or long lasting and may

be associated with problems that range from an occasional click of the jaw to severe chronic pain involving the entire orofacial region. Often one of the biggest challenges facing an individual with a TMD or TMD-related symptoms is finding the appropriate diagnosis and treatment, particularly given the divide between medicine and dentistry in the United States and much of the world—a divide that profoundly affects care systems, payment mechanisms, and professional education and training.

The national prevalence of TMDs is difficult to estimate due to challenges in conducting clinical examinations on a large scale, such that most prevalence data are based on self-reported symptoms associated with TMDs rather than examiner-verified classification. For example, one analysis of 2018 data found that an estimated 4.8 percent of U.S. adults (an estimated 11.2 to 12.4 million U.S. adults in 2018) had pain in the region of the TMJ that could be related to TMDs (see Chapter 3). Orofacial pain symptoms may or may not be related to TMDs. As discussed throughout this report, TMDs are a set of diverse and multifactorial conditions that can occur at different stages in an individual’s life with a range of manifestations and impacts on quality of life.

This report explores a broad range of issues relevant to improving the health and well-being of individuals with a TMD. To address the study’s Statement of Task (see Box 1-1), the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine appointed an 18-member committee with expertise in public health; pain medicine; basic, translational, and clinical research; patient advocacy; physical therapy; dentistry; self-management; TMDs and orofacial pain; oral and maxillofacial surgery; health care services; internal medicine; endocrinology; rheumatology; law; nursing; psychiatry; and communications. The study was sponsored by the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

The committee held five in-person meetings during the course of its work, including a public workshop in March 2019 during which a number of speakers provided their expertise on study topics and individuals with a TMD provided their insights on living with these disorders. Additionally, the committee heard from speakers at their first meeting (January 2019) and through two public web conference call meetings in June and July 2019 (see agendas in Appendix A). Furthermore, the committee gained many insights from public testimony provided in written format. The committee’s work involved extensive scientific literature searches and the review of a range of materials.

COMPLEXITY OF TMDs

The TMJs and associated structures are critically important to the function of the face, head, and entire human body. Not only do the movements of this joint support the survival functions of eating, drinking, breathing, and speaking, but facial movements are also essential for expressing human feelings and emotions.

The TMJs are among the most frequently used joints in the body, often opening and closing approximately 2,000 times daily (Hoppenfeld, 1976; Magee, 1999). Facial expression is critical for self-esteem and

self-identification as well as for expressing essential human emotions, such as joy or sadness, which form the basis for interpersonal interactions. All of these activities, ranging from the most demanding of chewing to the most subtle of breathing, require healthy functioning of both the TMJs and associated tissues. During joint movement, the two TMJs act through parallel efforts to move the semi-rigid jaw and connect the mandible to the temporal bone of the skull (see Chapter 2 and Appendix D).

The complexity of the varied conditions that are included in the set of disorders known as TMDs has been a challenge for individuals with a TMD, their family members, health care professionals,1 and researchers. Although these disorders have sometimes been lumped together as one entity (with terms such as temporomandibular joint disorder), recent efforts have focused on emphasizing that this is a set of disorders (see Chapter 2), and therefore that there is no one treatment or one care pathway for TMDs—one “size” does not fit all. Upon being diagnosed with a TMD, the goals are for each patient to know the specific type of disorder (or multiple TMDs) that he or she has and to be provided with an appropriate treatment plan specific to that diagnosis. The challenge (as described in Chapter 5) is that the evidence base for matching a specific treatment (or group of treatments) with a specific diagnosis is not yet fully developed so that in some cases, particularly for chronic conditions, much remains to be learned. While a small number of abnormalities of the TMJ require specific surgical operations to correct, the majority of TMDs have diffuse symptoms and may not respond predictably to one specific intervention. As discussed in Chapter 3, much also remains to be learned about the prevalence of specific TMDs.

The committee uses the broad definition of TMDs as a set of diseases and disorders related to alterations in the structure, function, or physiology of the masticatory system and that may be associated with other systemic and comorbid medical conditions. The term “TMDs” is used as an umbrella term to encompass disorders that can range from muscle or joint pain to joint disorders (including hypomobility or hypermobility of the joint) to joint diseases (including osteoarthritis) (see Chapter 2). The pain associated with TMDs can range from none to severe high-impact pain. TMDs can range from a single isolated condition to multi-system involvement and can be associated with other comorbid and systemic disorders and overlapping pain conditions (e.g., fibromyalgia, back pain, headache, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory arthritis). Emphasizing the plurality of conditions is important. TMD is not a single diagnosis, but requires

___________________

1 The committee uses the term “health care professionals” throughout the report to encompass all persons working in multiple health care fields including medicine, dentistry, nursing, physical therapy, dietary health, speech therapy, behavioral health, and complementary and integrative health.

further diagnostic work to identify the specific disease or disorder and the appropriate type of treatment. These issues are expanded on in Chapter 2.

CHALLENGES IN CARE: PATIENT EXPERIENCES

The committee greatly benefited from the input of individuals with a TMD and family members, many of whom face significant day-to-day challenges in living with a TMD. These challenges include difficulties in eating, in personal and social interactions, and in talking, which are often accompanied by severe ongoing pain. The committee received input from more than 110 individuals through in-person and online opportunities to testify at the committee’s public workshop (see Appendix A) and through written submissions to the study’s public access file.2 Among the many issues raised in these testimonies, several focused on the health care system and the care of individuals with a TMD. In particular, many individuals with a TMD or their family members commented on:

- Lack of coordinated care and abandonment—Individuals reported that they were often shuffled back and forth between clinicians in the medical and dental fields with little to no attention paid to a comprehensive approach to coordinated care. Patients also reported being abandoned by their dentists and other clinicians when the treatments did not work, with no referrals or other options provided.

- Over-treatment/harmful treatment—Many patients reported on having endured multiple TMD-related surgeries (in some cases more than 20), often with no resolution to their pain or with worsening symptoms. Other individuals reported that they had not had surgery but had had a removable oral appliance, orthodontic correction of the teeth, replacement of teeth, or some combination of these treatments.

- Impact on quality of life—Individuals with a TMD described how having a TMD has profound impacts on the quality of their day-today lives, from struggling in pain to kiss a loved one to challenges in dining out with friends or simply eating solid foods. Some individuals noted that the disorder affected their ability to work and to care for their families. Many described challenges in dealing with the emotional consequences of their condition and its treatment and with the episodic or ongoing pain that they experience.

- Expense—The financial burden of seeking and receiving care for a TMD was noted by individuals and family members. Some people

___________________

2 The study’s public access file is available through the National Academies Public Access Records Office (paro@nas.edu).

-

said that they had received limited insurance coverage, but for the most part, the coverage was paid out of pocket by the individual at costs of up to tens of thousands of dollars.

- Identifying qualified health care professionals—Individuals with a TMD and their families often expressed their frustration at not knowing where to turn for quality care. Primary care and internal medicine clinicians and general dentists often did not know how to help them locate qualified specialists. Patients were highly aware of the temporomandibular joint implant failures of the 1970s and 1980s and conveyed their concerns about the lack of quality treatment options for TMDs. Additionally, they noted that misleading advertising practices—in which clinicians claim to be experts but do not have the proper experience or evidence-based practices—further complicate access to quality care.

- Comorbidities—Many individuals with a TMD noted challenges with comorbid conditions including fatigue, widespread pain, fibromyalgia, depression, anxiety, and arthritic conditions.

Throughout the report, the committee has included a number of quotes excerpted from the testimony provided both by individuals with a TMD and by family members who consented to share their words in the hopes of moving this field forward and improving the prevention and care of TMDs.

This brief overview highlights only some of the challenges that continue to be faced by individuals with a TMD and by clinicians in diagnosing TMDs and identifying appropriate care for them. A part of the history of the treatment of TMDs centers on the synthetic implants often used from the late 1960s to early 1990s to replace the condyle, fossa, and articular disc of the TMJ (Myers et al., 2007). Many of these implants were either recalled by the Food and Drug Administration or voluntarily withdrawn from the market after they caused a range of adverse health outcomes including severe pain and functional joint impairment (see Chapter 5).

Patients have played and continue to play a major role in bringing attention to the need to advance the understanding of and ability to treat TMDs. The TMJ Association was founded in 1986 and is the major patient advocacy organization working on these issues and advocating for further research efforts and improvements in care in addition to providing support for individuals with a TMD and their family members (The TMJ Association, 2019a). The TMJ Association has worked with patients, federal agencies, researchers, clinicians, and manufacturers to develop and implement the TMJ Patient-Led RoundTable, a public–private collaboration working through the Medical Device Epidemiology Network (Kusiak et al., 2018), and it has organized a series of scientific conferences (The TMJ Association, 2019b). Other patient advocacy groups working on chronic pain issues

include the American Chronic Pain Association, U.S. Pain Foundation, and Chronic Pain Research Alliance.

IDENTIFYING THE APPROPRIATE MODEL FOR TMD CARE AND RESEARCH

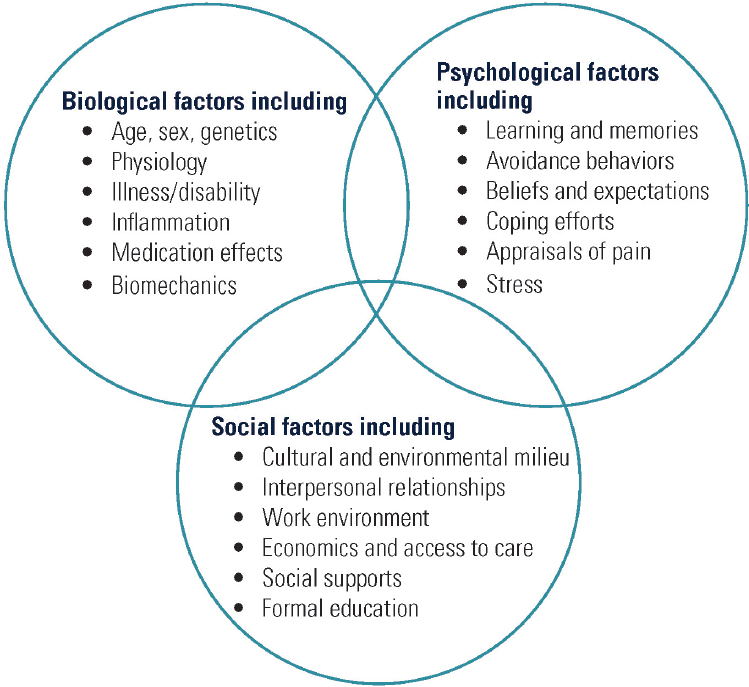

Because TMDs are not one disorder or disease, patients vary considerably in their initial complaints and in the type of health care professional from whom they first seek care. Also for this reason, neither the dental nor the medical model of care alone truly fits the needs of many TMD patients. The committee supports a biopsychosocial model of TMDs that is interdisciplinary and can be used across medicine and dentistry to focus on the total person’s health and well-being (see Chapter 6). The biopsychosocial model of pain provides a comprehensive heuristic for understanding and managing pain (Gatchel et al., 2007). It assumes that pain and its associated disability are the result of complex and dynamic interactions among physiological, psychological, and social factors that can maintain and amplify pain and disability. The use of a biopsychosocial model (see Figure 1-1) brings together the biological, psychological, and social influences and determinants of health and aims for a comprehensive approach to patient care (Engel, 1977). This model highlights the range of factors and interactions that may need to be considered in the care of individuals with a TMD. The diversity of concerns and symptoms often means that an interprofessional approach spanning dentistry and multiple fields of medicine is required to ensure that a TMD receives appropriate diagnosis and treatment. While many disorders and conditions benefit from a biopsychosocial model, TMDs provide a unique opportunity to explore the bridging of medical and dental models of care to benefit individuals.

The dental model of care is focused primarily on the physical restoration of the normal anatomy and movement of the facial structures, teeth, and bite. In the past TMDs were often viewed by patients and health care professionals as primarily within the scope of dental practice. Consequently, alterations to the occlusion as well as intraoral appliances (often termed mouth guards or oral splints) have frequently been the starting point in dentistry for addressing pain or other concerns related to TMDs. Patients who do not experience relief with these measures may be referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for an escalation of care. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons are dental specialists, often with medical degrees and extensive surgical training, with a focus on the surgical restoration of facial anatomy and function. Historically, however, this referral pathway within dentistry has led to a focus on interventions intended to restore altered facial joint anatomy. An improved understanding of TMDs has led to the realization that an expanded care model is necessary to provide the

holistic treatment that is often required to treat this disorder effectively and that non-intrusive treatments are considered the first approach in most cases.

The biomedical model of care generally focuses on assessing for a possible pathophysiology of the disease or disorder and identifying a treatment or care plan to alleviate or fix that problem. For TMDs, primary care clinicians may be less sure about the diagnostic approaches and the array of disorders requiring referrals to a specialist or specialists depending on the specific disorder. Orthopedics and rheumatology are among the specialties to which joint disorders are typically referred, for example, but historically patients with TMDs have generally not been referred to these specialty

areas. There is not a specific medical home for TMD care, particularly for individuals with complex cases. Many health fields are relevant for the care of patients with a TMD, including pain management, physical therapy, behavioral health and clinical psychology, chiropractic care, and integrative medicine. Specific dental and medical specialties need to take or share the lead in TMD care (see discussion in Chapter 6).

KEY THEMES

The committee’s work focused on a set of key themes (listed below) that have as their basis the core goals of health care developed in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) 2001 report Crossing the Quality Chasm: The New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001; see Box 1-2). The committee also drew on the work of the IOM’s 2011 report Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and

Research (IOM, 2011), the National Pain Strategy (HHS, 2016), and the Federal Pain Research Strategy (IPRCC, 2017).

For this report on TMDs, the committee focused on the following key themes:

- Recognize the spectrum of TMDs across medicine and dentistry. TMDs are a complex, heterogeneous, multifactorial set of disorders with varying treatments depending on the specific disorder. Depending on the specific type of TMD and its course, an interdisciplinary approach to care is often needed that includes multiple health care clinicians across medicine, dentistry, physical therapy, behavioral health, and integrative health.

- Emphasize person-centered care. The complexity of TMDs and the frequency of other comorbid health conditions necessitates an approach to care that focuses on the total health and well-being needs of each individual; accomplishing that principle requires adequate time for assessment and discussion with the patient.

- Ensure careful diagnosis and avoid harm. Diverse opinions and approaches to practice within the dental community and the lack of widely adopted evidence-based care pathways3 have led to poor treatment outcomes and overly aggressive treatment for many individuals with a TMD. Despite the best intentions of many dentists, this lack of applying non-intrusive treatment methods as the first step in treatment has often harmed individuals. Due to the complexities of TMDs, the committee urges an emphasis on prevention strategies, correct diagnosis, and thoughtful evidence-based treatment approaches.

- Foster an interdisciplinary approach to TMD care. Many areas of medicine, dentistry, nursing, behavioral health, physical therapy, and integrative health, as well as other health fields, contribute to TMD research and care of individuals with a TMD. Going beyond traditional silos and bridging the gaps between professions will be the key to making progress, as will be education and training for those individuals in TMD research and care.

- Explore the numerous research horizons. Significant opportunities are available for research across many fields of medicine, dentistry, other health sciences, and other areas of science to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying TMDs, develop an evidence base for care, and improve the implementation of best practices of care for individuals with a TMD.

___________________

3 In this report, evidence-based care is defined as care that uses current best evidence from well-designed studies, clinician expertise, and patient values and preferences in the care of individual patients and the delivery of health care services.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

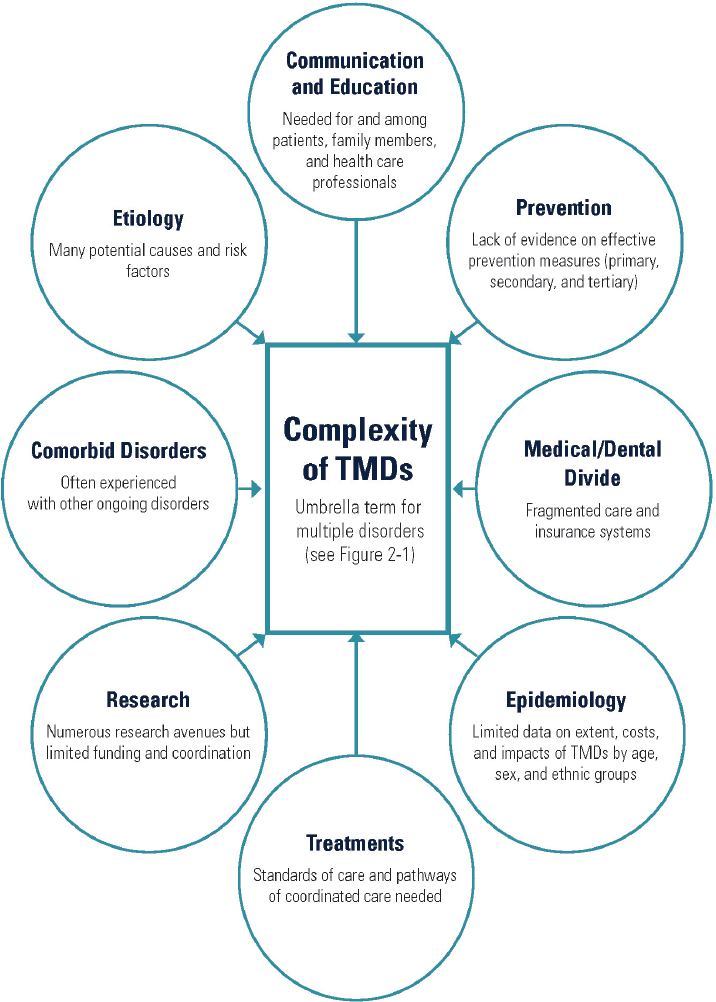

This report covers the breadth of the committee’s Statement of Task and the multiple aspects of the complexity of TMDs (see Figure 1-2).

In Chapter 2 the committee explores the definition and scope of TMDs, and in Chapter 3 it delves into what is known about the burden and costs of TMDs, with a focus on population-based studies. The broad scope and spectrum of research on TMDs is discussed in Chapter 4, including discussions on new horizons for TMD research. In Chapters 5 and 6 the care of individuals with TMDs is the focus, with discussions specific to improving the quality, access, and value of TMD care. Professional education and training are discussed in depth in Chapter 6, with an emphasis on health professional education. Raising awareness and increasing knowledge about TMDs for patients and for the general public is the focus of Chapter 7, with key messages identified. The report concludes in Chapter 8 with the committee’s recommendations for the short- and long-term actions that are needed to improve the health and well-being of individuals with a TMD.

REFERENCES

Engel, G. L. 1977. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 196(4286):129–136.

Gatchel, R. J., Y. B. Peng, M. L. Peters, P. N. Fuchs, and D. C. Turk. 2007. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychological Bulletin 133(4):581–624.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2016. National pain strategy: A comprehensive population health-level strategy for pain. https://www.iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHSNational_Pain_Strategy_508C.pdf (accessed October 3, 2019).

Hoppenfeld, S. 1976. Physical examination of the cervical spine and temporomandibular joint. In Physical examination of the spine and extremities. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange. Pp. 105–132.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: The new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2011. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IPRCC (Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee). 2017. Federal pain research strategy. https://www.iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/iprcc/FPRS_Research_Recommendations_Final_508C.pdf (accessed October 3, 2019).

Kusiak, J. W., C. Veasley, W. Maixner, R. B. Fillingim, J. S. Mogil, L, Diatchenko, I. Belfer, M. Kaseta, T. Kalinowski, J. Gagnier, N. Hu, M. Reardon, C. Greene, and T. Cowley. 2018. The TMJ Patient-Led RoundTable: A history and summary of work. http://mdepinet.org/wp-content/uploads/TMJ-Patient-RoundTable-Briefing-Report_9_25_18.pdf (accessed September 4, 2019).

Magee, D. J. 1999. Temporomandibular joint. In Orthopedic physical assessment. D. J. Magee, ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Co. Pp. 224–251.

Myers, S., S. Kaimal, J. Springsteen, J. Ferreira, C-C. Ko, and J. Fricton. 2007. Development of a national TMJ implant registry and repository: NIDCR’s TIRR. Northwest Dentistry 86(6):13–18.

The TMJ Association. 2019a. TMJ Association. http://www.tmj.org (accessed September 6, 2019).

The TMJ Association. 2019b. TMJA science meetings. http://www.tmj.org/Page/53/34 (accessed September 6, 2019).