1

Introduction

The Social Security Administration (SSA) administers two programs that provide disability benefits: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. SSDI provides disability benefits to people (under the full retirement age)1 who are no longer able to work because of a disabling medical condition. SSI provides income assistance for disabled, blind, and aged people who have limited income and resources regardless of their prior participation in the labor force (SSA, 2019a). Both programs share a common disability determination process administered by SSA and state agencies as well as a common definition of disability for adults: “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months” (SSA, 2017). Disabled workers might receive either SSDI benefits or SSI payments, or both, depending on their recent work history and current income and assets. Disabled workers might also receive benefits from other public programs such as workers’ compensation, which

___________________

1 Full retirement age had been 65 for many years. However, beginning with people born in 1938 or later, that age gradually increased until it reached 67 for people born after 1959. The 1983 Social Security Amendments included a provision for raising the full retirement age beginning with people born in 1938 or later. Congress cited improvements in the health of older people and increases in average life expectancy as primary reasons for increasing the normal retirement age (https://www.ssa.gov/planners/retire/ageincrease.html [accessed March 16, 2020]).

insures against work-related illness or injuries occurring on the job, but those other programs have their own definitions and eligibility criteria.2

This chapter provides the committee’s task and basic background information about SSA and its programs for adults as related to the committee’s task. It begins with a presentation of general information on SSDI and SSI, which both employ the same disability determination process.3 The chapter also presents information regarding the continuing disability reviews (CDRs), periodic reviews that determine whether disability benefit recipients’ conditions continue to be disabling. SSA must conduct CDRs at least once every 3 years unless a beneficiary’s condition is not expected to improve, in which case SSA will still perform a review once every 7 years. Thus, the frequency of scheduled CDRs is determined by the likelihood of improvement and is closely related to the committee’s task.

It should be noted that the focus of this report is on adults, and considerations of disabilities in children are not examined. Furthermore, the population of interest is those individuals whose condition significantly limits their ability to do basic work (such as lifting, standing, walking, sitting, and remembering) for at least 12 months. If the condition does not meet that requirement (i.e., 12-month minimum disability duration) SSA will find that the individual is not disabled.

The remainder of the chapter discusses the committee’s approach to the task, the evolving concepts of disability, the committee’s conceptualization of disability, and the organization of the entire report.

STATEMENT OF TASK

As SSA seeks to improve its criteria for determining the appropriate point at which it sets a “diary” for a CDR, it has requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) establish a consensus committee to study specific, long-lasting medical conditions for adults that are disabling for a length of time but that typically do not result in permanently disabling limitations, are responsive to treatment, and, after a specific length of time of treatment, improve to a point at which the conditions are no longer disabling.

In response to that request, the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies appointed a committee to conduct the study. Specifically, the National Academies convened a committee to:

___________________

2 There is no federal role in state workers’ compensation. State compensation programs vary widely with regard to coverage, benefits, and administrative practices (Social Security Bulletin, Volume 65, No. 4, 2005).

3 See 20 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 404, Subpart P.

- Identify and define the professionally accepted, standard measurements of outcomes improvement for medical conditions (for example, mortality and effectiveness of care);

- Identify specific, long-lasting (12-month duration or longer) medical conditions for adults in the categories of mental health disorders (such as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder), cancers (such as breast, skin, thyroid), and musculoskeletal disorders (such as disorders of the back, osteoarthritis, other arthropathies) that are disabling for a length of time, but typically (for most people with the condition) do not result in permanently disabling limitations, are responsive to treatment, and, after a specific length of time of treatment, improve to the point at which the conditions are no longer disabling; and

- For the conditions identified in Objective 2 (above):

- Describe the professionally accepted diagnostic criteria, the average age of onset, and the gender distribution for each condition;

- Identify the types of medical professionals involved in the care of a person with the condition;

- Describe the treatments used to improve a person’s functioning, the settings in which the treatments are provided, and how people are identified for the treatments;

- Describe the length of time from start of treatment until the person’s functioning improves to the point of which the condition is no longer disabling and specific ages where improvement is more probable;

- Identify the laboratory or other findings used to assess improvement, and, if patient self-report is used, identify alternative methods that can be used to achieve the same assessment; and

- Explain whether pain is associated with the condition, and, if so, describe the types of treatment prescribed to alleviate the pain (including alternatives to opioid pain management such as non-pharmacological and multimodal therapies).

SSA specifically directed the committee not to discuss issues related to access to treatment. The following language is in the National Academies contract with SSA:

The committee shall not describe issues with respect to access to treatments. While SSA recognizes people may have difficulty accessing care or particular forms of treatment, some do successfully access those treatments, and the agency receives information about those treatments in the medical records SSA considers when making disability determinations

and conducting continuing disability reviews (CDRs). SSA is interested in receiving information about the types of treatments available, the requirements for receiving the treatments, what receipt of the treatments indicates about the severity of the medical condition, the likelihood of improvement when receiving the treatments, and the period over which the improvement would be expected. SSA understands improvement is not certain in all cases. SSA is interested in learning about conditions that are more likely than not to improve. SSA makes individual decisions on each case based on all the evidence they receive.

SOCIAL SECURITY DISABILITY INSURANCE PROGRAM

The SSDI program was authorized by Title II of the Social Security Act and enacted in 1956 to provide benefits to disabled workers who have paid into the Social Security system and who are younger than the Social Security full retirement age. The goal of SSDI is to replace a portion of a worker’s income in the event of illness or disability in amounts related to the worker’s former earnings. The SSDI program also provides Medicare coverage after a 2-year waiting period. SSDI is financed by the Social Security payroll tax, so any person who qualifies as disabled, according to the SSA definition of disability (inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity), and has paid Social Security taxes long enough to achieve sufficient work credits can receive SSDI. In 2018 there were 2,073,293 applications filed at Social Security field offices, teleservice centers, and electronically on the Internet, and 733,879 awards were granted (SSA, 2020).

About one-third of disabled-worker beneficiaries have musculoskeletal conditions (such as severe arthritis or back injuries) as a primary diagnosis (see Chapter 5). Another one-third has a diagnosis of a mental disorder (see Chapter 4). Others have life-threatening conditions, such as advanced-stage cancer (see Chapter 3), end-stage renal disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (SSA, 2018a).

SOCIAL SECURITY SUPPLEMENTAL SECURITY INCOME PROGRAM

The SSI program, authorized by Title XVI of the Social Security Act and enacted in 1972, is a nationwide federal assistance program administered by SSA. It is funded through general revenues, and, in addition to establishing disability, the applicant must also meet the nonmedical income and resource eligibility requirements, which are based on need. The basic purpose of the SSI program is to ensure a minimal income to people who are blind or disabled and who have limited income and resources. In 2019 the SSI Federal Payment Standard was $771 per month for an individual

and $1,157 per month for a couple. SSI recipients are also eligible to receive Medicaid coverage (without a waiting period as is required with SSDI and Medicare coverage).4

Disability Insurance Under the Social Security Administration

Social Security only pays benefits for total disability; it does not pay benefits for partial disability or for short-term disability. The SSA definition of disability is different from other disability program definitions. To be eligible for benefits, a person must be insured for benefits, be younger than full retirement age, have filed an application for benefits, and have an SSA-defined disability. An applicant must have worked long enough to meet the insured requirement. The number of work credits an applicant needs to qualify depends on the individual’s age. The formal SSA definition of disability is described in Section 223(d)(1) of the Social Security Act. It is an

inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months, or in the case of an individual who has attained the age of 55 and is blind (within the meaning of blindness as defined in section 216(i)(1)), inability by reason of such blindness to engage in substantial gainful activity requiring skills or abilities comparable to those of any gainful activity in which the individual has previously engaged with some regularity and over a substantial period of time.

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION’S DISABILITY DETERMINATION PROCESS

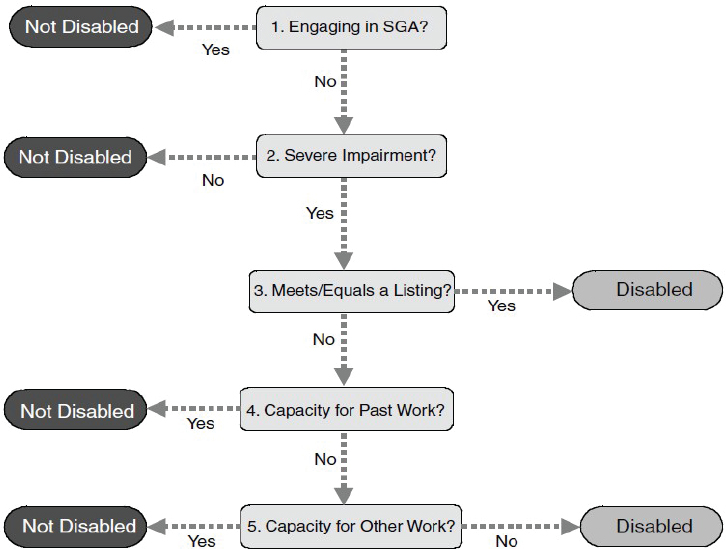

SSA has a five-step sequential evaluation process (see Figure 1-1) to determine whether someone is medically eligible for SSDI or SSI benefits.5 At the first step, SSA determines whether the applicant is currently engaging in substantial gainful activity (SGA), defined as earning more than the SGA threshold, which in 2019 was set at $1,220 per month for non-blind people and $2,040 per month if a person is blind (SSA, 2019c). If the applicant is currently engaging in SGA, SSA will find that the applicant is not disabled.

___________________

4 Some states have a separate process for determining Medicaid eligibility, but all states are required to offer Medicaid to disabled SSI beneficiaries. According to SSA, in “most states, if you are an SSI beneficiary, you might be automatically eligible for Medicaid; an SSI application is also an application for Medicaid. In other states, you must apply for and establish your eligibility for Medicaid with another agency. In these states, SSA will direct you to the office where you can apply for Medicaid” (SSA, 2019b).

5 20 CFR § 404.1520.

NOTES: In 2019, substantial gainful activity (SGA) is defined as earning $1,220 or more per month from working, or $2,040 for blind people. If SSA determines that an individual is working at the SGA level, he or she is ineligible for benefits.

SOURCES: 20 CFR § 404.1520 and 416.920.

At the second step, the disability examiner considers the medical severity and expected duration of the applicant’s impairment. If the applicant’s impairment or combination of impairments is not severe or has not lasted or is unlikely to last at least 12 months, SSA will find that the applicant is not disabled. At the third step, the disability examiner determines whether the impairment “meets” or “medically equals” one of the items on the Listing of Impairments (discussed in detail in the next section). If SSA finds that the applicant’s impairment meets or medically equals a listing, then SSA will find that the applicant is disabled and allowed benefits.

Otherwise, the examiner moves on to the fourth step, at which point the disability examiner assesses the applicant’s “residual functional capacity” (the maximum level of physical or mental performance that the applicant can achieve, given the functional limitations resulting from his or her medical impairment[s]) and determines whether the applicant is able to

engage in any of his or her past relevant work; if so, the applicant will be found not to be disabled.6

At the fifth and last step, SSA will determine whether the applicant can perform any work in the national economy on the basis of the assessment of residual functional capacity and the applicant’s age, education, and work experience. If the applicant can make an adjustment to other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy, SSA will find that the person is not disabled; otherwise, SSA will find that he or she is disabled.7Figure 1-1 provides a visual model of the steps involved in the evaluation.8

Finally, SSA notes that it is committed to providing benefits quickly to applicants whose medical conditions are so serious that they obviously meet SSA’s disability standards. Thus, SSA has two different fast-track processes—compassionate allowances (CALs) and Quick Disability Determination (QDD)—that enable SSA to expedite review and decisions for some applications. The CAL process incorporates technology to quickly identify diseases and other medical conditions that, by definition, meet SSA’s standards for disability benefits. Those conditions include certain cancers, adult brain disorders, and a number of rare disorders that affect children (SSA, 2019d). The QDD process uses a computer-based predictive model to screen initial applications and identify cases in which a favorable disability determination is highly likely and medical evidence is readily available in an effort to fast-track a (positive) determination (SSA, 2019e). Those fast-track processes are only used to arrive at positive decisions; an applicant will be found not disabled only after SSA fully develops the evidence in the case and applies the full sequential evaluation process.

The Listing of Impairments

The third step of the sequential evaluation process relies on the Listing of Impairments9 (hereafter Listings) to identify cases that can be allowed regardless of the applicant’s age, education, or work experience. The Listings are organized by 14 body systems for adults (see Box 1-1) and, for each system, include impairments that SSA considers severe enough to prevent an adult from performing any gainful activity. According to the SSA Office of Inspector General (OIG) (2015), “the Listings help ensure that disability determinations are medically sound, claimants receive equal

___________________

6 CFR § 404.1560(b).

7 CFR § 404.1560(c).

8 For additional details on the types of medical evidence considered in the disability determination process and on the training and credentials required of disability examiners and medical/psychologic consultants, refer to The Promise of Assistive Technology to Enhance Activity and Work Participation (NASEM, 2017).

9 Found at 20 CFR Part 404, Subpart P.

treatment based on the specific criteria, and disabled individuals can be readily identified and awarded benefits, if appropriate.” Applicants whose impairments do not meet or medically equal a Listing can still be determined to be disabled at step 5 of the sequential evaluation process on the basis of the combination of their residual functional capacity, age, education, and work experience.

Although there has been an established “listing of medical impairments” since the disability program began in 1956, SSA did not publish the Listings in its disability regulations until 1968.10 Since then it has revised the Listings periodically to reflect recent advances in medical knowledge. In 2003 SSA implemented a new process for revising the Listings, which was designed to ensure regular updates and monitoring of the Listings about every 3–4 years (OIG, 2009). Seven body systems were last updated in the Listings between 2009 and 2015. The SSA OIG recommended that by the end of fiscal year 2020, SSA should ensure that all Listings updates are less than 5 years old and that SSA continue to update them as needed to reflect current medical knowledge and advances in technology (OIG, 2015). Four more body systems (respiratory, neurologic, mental, and immune system disorders) were updated between 2016 and 2017.

___________________

10 See https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0434101005 (accessed January 15, 2019) for an explanation of the Listings before 1968 (SSA, 1990).

After a body system is updated, SSA begins the process of identifying the necessary revisions again. The process begins with information gathering both within the agency (e.g., analyzing data, conducting a literature review, and obtaining feedback from adjudicators) and outside the agency (e.g., discussions with the public including medical experts and soliciting comments from the public via an advance notice of proposed rulemaking). SSA develops proposed changes to the body system(s) based on its information gathering and case reviews and drafts a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM). The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as well as other federal agencies (e.g., the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs) review and comment on the draft NPRM. SSA obtains OMB approval and publishes the NPRM in the Federal Register for public comment. SSA reviews and responds to public comments, revises the proposed rule as needed, and drafts a final rule. OMB reviews the final rule, and SSA obtains OMB approval and publishes the final rule in the Federal Register.

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION’S CONTINUING DISABILITY REVIEW

Individuals receiving SSDI benefits or SSI payments (based on disability or blindness) must continue to meet the disability requirements of the law. SSA periodically reviews the cases of SSDI beneficiaries and SSI recipients to determine whether the individuals continue to be disabled. That review is called a CDR. If SSA determines that an individual is no longer disabled (or blind), benefits will stop. The Social Security Act requires that SSA perform a CDR at least once every 3 years for beneficiaries with an impairment in which medical improvement is possible and more frequently if SSA determines that an individual has a medical condition that is expected to improve sooner. Even in the case of medical conditions that are not expected to improve, SSA will still review each claimant’s case once every 7 years. Furthermore, income, resources, and living arrangements will also be reviewed during the CDR (SSA, 2019f).

If an individual is not engaging in SGA and does not meet or equal a listing in the current Listings, SSA determines whether medical improvement has occurred in the individual’s impairment(s). SSA defines “medical improvement” as any decrease in the medical severity of a physical or mental condition that was present at the time of the person’s most recent favorable medical decision when he or she was disabled or continued to be disabled. A determination that there has been a decrease in medical severity must be based on an improvement in the symptoms, signs, or laboratory findings associated with the person’s medical condition.

SSA considers two categories of medical improvement to enable a careful consideration of all factors related to whether a person continues to receive SSDI or SSI:

- Medical improvement not related to ability to do work: Medical improvement is deemed to be not related to an individual’s ability to work if there has been a decrease in the severity of the impairment(s) present at the time of the most recent favorable medical decision but the individual still meets or equals the listing, or any subsection of the listing, that that person met at his or her most recent favorable decision or there has been no increase in the individual’s functional capacity to do basic work activities. If there has been any medical improvement in the individual’s impairment(s), but it is not related to the person’s ability to do work and none of the exceptions apply, that individual’s benefits will be continued.

- Medical improvement that is related to ability to do work: Medical improvement is related to an individual’s ability to work if there has been a decrease in the severity of the impairment(s) present at the time of the most recent favorable medical decision and that person no longer meets or equals the listing, or any subsection of the listing, that the individual met at his or her most recent favorable decision or, if that person did not meet a listing at his or her most recent favorable decision, there has been an increase in his or her functional capacity to do basic work activities. A determination that medical improvement is related to an individual’s ability to do work has occurred does not necessarily mean that the person’s disability will be found to have ended unless it is also shown that that person is currently able to engage in substantial gainful activity (see CFR § 404.159).

Social Security Administration Policy for the Frequency of Continuing Disability Reviews

As noted above, when SSA initially finds a person disabled, it sets a “diary” for an appropriate time at which to conduct a CDR. Under the law, SSA must review all disability beneficiaries at least once every 3 years (unless the beneficiary is permanently disabled). The frequency of the review is based on the likelihood of improvement. Thus, the diary is based on when, or if, SSA expects medical improvement. Categories of review schedules are briefly summarized below (see SSA [2018b] for a thorough description of this policy).

Medical Improvement Expected

SSA will schedule a review of an individual with an impairment expected to improve at intervals from 6 to 18 months following the most recent determination or decision that the individual is disabled or that disability is continuing. The review category, medical improvement expected (MIE), applies to individuals with impairments, which at the time of initial entitlement or after further review are expected to improve sufficiently to permit the individuals to engage in SGA. An MIE schedule is set when the individual will “probably” or “almost certainly” meet the medical improvement standard and be able to work or else “is in the process of a full recovery or is experiencing significant, sustained, and progressive improvement” (SSA, 2015). This category is not used when an impairment is chronic or progressive.

Medical Improvement Not Expected

SSA schedules reviews of an individual with an impairment not expected to improve no less frequently than once every 7 years but no more frequently than once every 5 years. These medical improvement not expected (MINE) reviews apply to individuals with impairments at initial entitlement or after further review in which any improvement is not expected. These are extremely severe impairments shown, on the basis of administrative experience, to be at least static but more likely to be progressively disabling of themselves or by reason of impairment complications. The individual is unlikely to engage in SGA. SSA considers the interaction of the individual’s age, impairment consequences, and the lack of recent attachment to the labor market in determining whether an impairment is expected to improve. A MINE schedule is generally set when an individual is 54.5 years or older, has certain case characteristics found to infrequently result in cessation, or “when the case facts clearly demonstrate that cessation under the MIRS [medical improvement review standard] is not medically possible” (SSA, 2009).

Medical Improvement Possible

SSA will schedule a review (at least once every 3 years) of an individual with an impairment in which any improvement is possible, but which cannot be accurately predicted within a given period of time, referred to as medical improvement possible (MIP). The review is applicable to individuals with impairments at the time of initial entitlement or after subsequent review in which SSA considers any improvement possible but not probable within 3 years. In such cases improvement may occur, so that an individual

might return to SGA, but SSA cannot predict improvement with any accuracy based on current experience and the facts of the particular case. Generally this category is the catch-all for any individual who does not fit in the MIE or MINE categories.

APPROACH TO THE TASK

A 15-member committee was formed to address the task. Members with diverse backgrounds and expertise were appointed to focus on the different aspects of the task. Specifically, the members have expertise in various branches of clinical medicine (mental health, oncology, and musculoskeletal disorders) as well as in biostatistics and epidemiology, health care policy, and health outcomes research.

The committee organized itself into three groups: cancer, mental health, and musculoskeletal. Each group had experts in the specific disease category that was being studied in addition to a health outcomes researcher or a biostatistician and epidemiologist. Each group considered the specific disease categories listed in the Statement of Task and identified the diseases within those categories that they would study. Each disease outcome chapter provides additional information about the diseases chosen, but in general the committee considered the burden of the disease or the possibility for improvement, or both.

The committee met five times. It sponsored two open meetings, which enabled SSA representatives and the committee members to interact directly and discuss the committee’s charge. In support of the committee’s discussions and deliberations, the committee instructed the staff to conduct targeted literature searches and to gather information from relevant texts, scientific journals and professional societies, and federal sources.

Staff initially reviewed more than 1,157 titles and abstracts; those were narrowed to about 528 studies, which the committee members carefully reviewed for relevance to the committee’s task. The review began with a search of online databases for U.S. and international English-language literature from 2008 through 2018. This search covered PubMed, Scopus, and Proquest as well as the SSA and the National Academies Press websites. A second search of the same databases was conducted for the years 2008–2018 to capture systematic reviews and meta-analyses for key words not previously included in the first search. All of the searches performed were specifically related to the committee’s chosen disorders and to those references that were most relevant to long-term disability with the potential to return to work. In the case of several disorders, for which there were a limited number of systematic reviews or meta-analyses, additional searches were carried out for reviews broadened to include randomized controlled trials. Committee members and project staff identified additional literature

and information using traditional academic research methods and online searches throughout the course of the study.

The committee used a variety of resources to supplement its review of the literature. The committee examined systematic reviews, when available, for the medical conditions being studied, and also relied on published guidelines, particularly if they had been through an external review process. The committee notes, however, that a major limitation of the studies it reviewed is the lack of data on return to work. Additionally, it should be noted that the terms “disability,” “function,” and “impairment” are used differently by the various authors in the many studies and reports reviewed, and the committee did not attempt to harmonize or reinterpret the different uses of those terms.

EVOLVING CONCEPTS OF DISABILITY

The focus of this section is the evolution of the concept of disability, including its definitions and different disability frameworks. Disability has many different definitions depending on whether it is being discussed in a political/policy, societal, or medical setting. Disability is defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “a physical, mental, cognitive, or developmental condition that impairs, interferes with, or limits a person’s ability to engage in certain tasks or actions or participate in typical daily activities and interactions.”11

In the context of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), “disability” is a legal term rather than a medical one. The ADA’s definition of disability is different from how it is defined in the dictionary and under various laws, such as those for SSDI-related benefits. The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity. It includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. In enacting the ADA, Congress recognized that physical and mental disabilities in no way diminish a person’s right to fully participate in all aspects of society, yet many people with physical or mental disabilities have been precluded from doing so because of prejudice and the failure to remove societal and institutional barriers. While the ADA definition of disability focuses on a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, SSA’s definition of disability (as noted above) is based on one’s ability to work, specifically the “inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result

___________________

11 See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disability (accessed March 16, 2020).

in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”12

Conceptual Frameworks of Disability

Conceptual frameworks and definitions of disability have evolved over the years from a “medical” model to a broader social model. For many years the prevailing model of disability was the medical model, in which disability was considered to be a result of impairment of body functions and structures, including the mind, and caused by disease, injury, or health conditions. As such, any disability was viewed primarily as an individual’s medical problem in need of treatment (Goering, 2015; Haegel and Hodge, 2016). However, the medical model has limitations, including not accounting for comorbid conditions or symptoms; people with more comorbid conditions generally have more functional limitations (Hung et al., 2012). Furthermore, the medical model does not recognize that there is not a direct correspondence between disability (as measured by functional status) and the presence of disease. Most people with chronic disease have no reported disability, for instance (Reichard et al., 2015). Conversely, some people with a loss of function have no active disease as the cause of their loss of function, or their disease might be difficult to measure objectively in a medical setting (e.g., chronic pain). Impairment due to a specific loss of function caused by a specific disease does not capture a person’s overall ability to function, which is likely affected by many other factors. Thus, disease and function might overlap, but not in a consistent way, and the overlap is likely to be different for each disease or existing comorbid conditions and diseases. The relationships between different diseases and disability have changed over time and likely parallel changes in treatment, life expectancy, comorbid conditions, and other factors (Hung et al., 2012).

According to the conceptual framework of disability developed by sociologist Saad Nagi (1965), disability is the expression of a physical or a mental limitation in a social context. Nagi specifically viewed the concept of disability as representing the gap between a person’s capabilities and the demands created by the social and physical environments (Nagi, 1965, 1976, 1991).

Similarly, in Disability in America (IOM, 1991) it is noted that people with medically determinable functional limitations are not inherently disabled, that is, incapable of carrying out their personal, familial, and social roles, but rather it is the interaction of their physical or mental limitations with social and environmental factors that determine whether they have a disability. Thus, it is important to have a conceptual framework for

___________________

12 42 U.S. Code § 423.

understanding disability not only as a series of consequences of disease or injury, but also as a consequence of people’s relationship with their environments—environments that might be supportive of participation in society or that might present obstacles to such participation.

A later Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Enabling America (IOM, 1997), relied on the conceptual framework found in Disability in America (IOM, 1991) but made some refinements to clarify the interaction between the person and the environment and the dynamics of the “enabling/disabling” process. The two IOM reports included quality of life as an important concept in understanding the impact of health conditions, impairments, functional limitations, and disabilities on people’s sense of well-being in relation to their personal goals and expectations.

The World Health Organization developed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),13 a framework for describing and organizing information on functioning and disability. The ICF provides a standard language and a conceptual basis for the definition and measurement of health and disability, integrates the major models of disability, and recognizes the role of environmental factors in the creation of disability as well as the relevance of associated health conditions and their effects. Furthermore, it provides a standardized, internationally accepted language and conceptual framework to facilitate communication across national and disciplinary boundaries. Similar to previous disability frameworks, the ICF attempted to provide a comprehensive view of health-related states from biologic, personal, and social perspectives (see Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF [WHO, 2002]).

In contrast to the medical model, the social model of disability relies on a sharp distinction between impairment and disability (Goering, 2015). The social model takes into consideration the role of the environment and societal factors in the concept of disability. As noted in Patel and Brown (2017), disability is based on the fact that, by itself, any functional impairment at an individual level might not create disability, but sociocultural expectations combined with the built environment limit a person’s ability to engage in a productive role. As researchers and practicing clinicians have recognized the important limitations of the medical model of disability, the conceptualization of disability has shifted toward a social model of disability, which does not consider the cause of the loss of a specific functional ability but rather the ability of the individual to function in a specific environment (Goering, 2015; Palmer and Harley, 2012). As noted by the

___________________

13 The ICF was endorsed in May 2001 by the World Health Assembly as a member of the family of International Classifications, the best known of which is the International Classification of Diseases.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2019), disability is viewed as how people with disability interact with their environment:

Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others (Article 1).

Similarly, and as noted above, the ICF measures disability and includes multiple dimensions of human functioning, synthesizing biologic, psychologic, and social and environmental aspects (Kostanjsek, 2011; Palmer and Harley, 2012; Üstün et al., 2010).

Thus, there are different models of disability, and different agencies and organizations have defined disability in different ways for various purposes. However, most definitions include the concept of a physical or mental impairment combined with the inability to fulfill social roles or expectations. The definition used by SSA incorporates a length of time and whether a person can perform work (i.e., “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months”).

The Committee’s Conceptualization of Disability

The committee members considered the issue of general medical improvement versus functional improvement, as they are keenly aware that disability models have expanded beyond a linear conception of medical conditions as the sole determinants of disability. Contemporary models now include the potent social, economic, and environmental factors that determine the extent to which an individual can meet his or her functional requirements. Those models conceptualize disability as a co-created entity that reflects an aggregate of individual, societal, and environmental factors. More specifically, an individual may be severely limited in one context but able to maintain independence and gainful employment in another. The committee strongly endorses the social model of disability and acknowledges that social and environmental factors greatly affect health outcomes. However, the committee focused on the medical model in this report, given the Statement of Task’s focus on medical and functional improvement and its request that the committee “shall not describe issues with respect to access to treatments.”

As has been amply and comprehensively highlighted in the 2019 National Academies report Functional Assessment for Adults with Disabilities, correlations between medical and functional outcomes, even when driven by a common disease process, are moderate at best. As a consequence, inferences about an individual’s work capability made solely on the basis of his or her medical outcomes are vulnerable to inaccuracies. Functional outcomes reflect the aggregate effects of physical and cognitive impairments as well as medical morbidities. As such they often align more closely than medical outcomes with the capabilities required for gainful employment. Additionally, when these outcomes accurately measure global functioning, they have the potential to reflect the net disabling effects of an individual’s multiple impairments and comorbidities. That potential is notable because these latter processes are frequently dynamic, relapsing and remitting, and affected by treatments and toxicities in a manner that is imperfectly captured in health records.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Chapter 2 briefly examines issues that overlap across the three disease categories, such as pain, comorbidities, and toxicities of therapies. Chapter 3 focuses on cancers and cancer-related impairments that might improve with treatment, Chapter 4 focuses on mental health disorders, and Chapter 5 concentrates on musculoskeletal conditions. Each of those chapters attempts to address all of the questions in the Statement of Task related to the specific medical condition being studied; however, the formats of the chapters are not identical. Chapters 3 to 5 each have their own internal organization that is specific to the condition discussed. There is an appendix to provide the reader with additional details relevant to the mental health disorders chapter.

REFERENCES

Goering, S. 2015. Rethinking disability: The social model of disability and chronic disease. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 8(2):134–138.

Haegele, J. A., and S. Hodge. 2016. Disability discourse: Overview and critiques of the medical and social models. Quest 68(2):193–206.

Hung, W. W., J. S. Ross, K. S. Boockvar, and A. L. Siu. 2012. Association of chronic diseases and impairments with disability in older adults: A decade of change? Medical Care 50(6):501–507.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1991. Disability in America: Toward a national agenda for prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1997. Enabling America: Assessing the role of rehabilitation science and engineering. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kostanjsek, N. 2011. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems. BMC Public Health 11(Suppl 4):S3.

Nagi, S. Z. 1965. Some conceptual issues in disability and rehabilitation. In Sociology and rehabilitation, edited by Sussman, M. B., pp. 100–113. Washington, DC: The American Sociological Association.

Nagi, S. Z. 1976. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Health and Society 54(4):439–467.

Nagi, S. Z. 1991. Disability concepts revisited: Implications for preventions. In Disability concepts revisited: Implications for prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Functional assessment for adults with disabilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

OIG (Office of Inspector General). 2009. The Social Security Administration’s listing of impairments. A-01-08-18023 SSA. https://oig.ssa.gov/sites/default/files/audit/full/html/A-01-08-18023_7.html (accessed January 3, 2020).

OIG. 2015. The Social Security Administration’s listing of impairments. A-01-15-50022 SSA. https://oig.ssa.gov/sites/default/files/audit/full/pdf/A-01-15-50022.pdf (accessed January 3, 2020).

Palmer, M., and D. Harley. 2012. Models and measurement in disability: An international review. Health Policy and Planning 27(5):357–364.

Patel, D. R., and K. A. Brown. 2017. An overview of the conceptual framework and definitions of disability. International Journal of Child Health and Human Development 10(3):247–252.

Reichard, A., S. P. Gulley, E. K. Rasch, and L. Chan. 2015. Diagnosis isn’t enough: Understanding the connections between high health care utilization, chronic conditions and disabilities among U.S. Working age adults. Disability and Health Journal 8(4):535–546.

SSA (Social Security Administration). 1990. Program operations manual system (POMS). https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0434101005 (accessed January 15, 2019).

SSA. 2009. Program operations manual system—DI 26525.040—the mine or mine-equivalent diary—general. https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0426525040 (accessed November 15, 2019).

SSA. 2015. Program operations manual system (POMS)—DI 26525.020 the MIE diary—general. https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0426525020 (accessed November 15, 2019).

SSA. 2017. Disability evaluation under Social Security listing of impairments—adult listings (part A). https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/AdultListings.htm (accessed January 12, 2019).

SSA. 2018a. Annual statistical report on the Social Security Disability Insurance program, 2017. No. 13-11826 SSA. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2017/di_asr17.pdf (accessed January 12, 2019).

SSA. 2018b. Program operations manual system (POMS). https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0428001020 (accessed January 15, 2019).

SSA. 2019a. Understanding Supplemental Security Income (SSI) eligibility requirements—2019 edition. https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-eligibility-ussi.htm (accessed January 12, 2019).

SSA. 2019b. Understanding Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and other government programs—2019 edition. https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-other-ussi.htm (accessed January 15, 2019).

SSA. 2019c. Substantial gainful activity. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/COLA/sga.html (accessed May 1, 2019).

SSA. 2019d. Compassionate allowances. https://www.ssa.gov/compassionateallowances (accessed May 1, 2019).

SSA. 2019e. Quick disability determinations (QDD). https://www.ssa.gov/disabilityresearch/qdd.htm (accessed May 1, 2019).

SSA. 2019f. Understanding Supplemental Security Income continuing disability reviews—2019 edition. https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-cdrs-ussi.htm (accessed January 15, 2019).

SSA. 2020. Selected data from Social Security’s disability program. https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/STATS/dibStat.html (accessed January 28, 2020).

UN (United Nations). 2019. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)—Article 1 Purpose. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-1-purpose.html (accessed November 17, 2019).

Üstün, T. B., World Health Organization, N. Kostanjsek, S. Chatterji, and J. Rehm. 2010. Measuring health and disability: Manual for WHO disability assessment schedule WHODAS 2.0. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2002. Towards a common language for functioning, disability, and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.