1

Introduction

A social instinct is implanted in all [people] by nature. . . .

—Aristotle, Politics, 350 B.C.E., Jowett (2009)

The scientific evidence is convincing. Strong social ties are good for one’s health.

Social isolation (the objective state of having few social relationships or infrequent social contact with others) and loneliness (a subjective feeling of being isolated) are serious yet underappreciated public health risks that affect a significant portion of the population. Approximately one-quarter (24 percent) of community-dwelling Americans aged 65 and older are considered to be socially isolated, and a significant proportion of adults in the United States report feeling lonely (35 percent of adults aged 45 and older and 43 percent of adults aged 60 and older) (Anderson and Thayer, 2018; Cudjoe et al., 2020; Perissinotto et al., 2012). In spite of some challenges related to the measurement of social isolation and loneliness, current evidence suggests that many older adults are socially isolated or lonely (or both) in ways that put their health at risk. For example:

- Social isolation significantly increases a person’s risk of mortality from all causes, a risk that may rival the risks of smoking, obesity, and physical activity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017);

- Being socially connected in a variety of ways is associated with having a 50 percent greater likelihood of survival, with some indicators of social integration being associated with a 91 percent greater likelihood of survival (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010);

- Social isolation has been associated with a 29 percent increased all-cause risk for mortality and a 25 percent increased risk for cancer mortality (Fleisch Marcus et al., 2017; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015);

- Loneliness has been associated with higher rates of clinically significant depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Beutel et al., 2017);

- Loneliness has been associated with a 59 percent increased risk of functional decline and 45 percent increased risk of death (Perissinotto et al., 2012);

- Poor social relationships (characterized by social isolation or loneliness) have been associated with a 29 percent increased risk of incident coronary heart disease and a 32 percent increased risk of stroke (Valtorta et al., 2016a);

- Loneliness among heart failure patients has been associated with a nearly four times increased risk of death, 68 percent increased risk of hospitalization, and 57 percent increased risk of emergency department visits (Manemann et al., 2018); and

- Social isolation has been associated with an approximately 50 percent increased risk of developing dementia (Kuiper et al., 2015; Penninkilampi et al., 2018).

Understanding the full scope and complexity of the influence of social relationships on health is challenging. In addition to the absolute number or extent of social relationships, the quality of such relationships is also important for their impact on health. As such, two aspects of social relationships, social isolation and loneliness, have become most prominent in the scientific literature. While both social isolation and loneliness can affect health throughout the life course, this report focuses specifically on the health and medical impacts of social isolation and loneliness among adults aged 50 and older. Of note, it is incorrect to assume that all older people are isolated or lonely. Rather, older adults are at increased risk for social isolation and loneliness because they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone, the loss of family or friends, chronic illness, and sensory impairments. Over a life course, social isolation and loneliness may be episodic or chronic, depending on an individual’s circumstances and perceptions.

Many approaches have been taken to improve social connections for individuals who are socially isolated or lonely, but finding opportunities to intervene may be most challenging for those who are at highest risk. For example, people who do not have consistent interactions with others (e.g., have unstable housing, do not belong to any social or religious groups, or do not have significant personal relationships) may never be identified in their own communities. However, nearly all persons who are 50 years of age or older interact with the health care system in some way, regardless of where they fall on the social isolation or loneliness continuum, and so this interaction may serve as a touchpoint to identify those who are isolated or lonely. Therefore, this report focuses on the role of the health care system as a key and relatively untapped partner in efforts to identify, prevent, and mitigate the adverse health impacts of social isolation and loneliness in older adults.

STUDY CONTEXT

A systematic and rigorous science of social relationships and their consequences, especially in terms of health, emerged in the latter part of the 20th century as part of a broader recognition of the role of social determinants of health. By the beginning of the 21st century, several aspects of social relationships were being studied systematically in research and identified as potential influences on human health. Only recently have the adverse health effects of social isolation and loneliness received public attention nationally and internationally through governmental initiatives, the work of nonprofit organizations, and mass media coverage (Anderson and Thayer, 2018; Brody, 2017; DiJulio et al., 2018; Frank, 2018; Hafner, 2016; Khullar, 2016). For example, in January 2018, Theresa May, prime minister of the United Kingdom, established and appointed a Minister of Loneliness to develop policies for both measuring and reducing loneliness (Yeginsu, 2018).

In his keynote address for the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 2019 Annual Educational Conference, Vivek Murthy, the 19th Surgeon General of the United States, spoke of an “epidemic of loneliness” that he recognized during his tenure as Surgeon General, stating,

I see [loneliness] actually as a primary concern, not just a health concern but as a concern as a society. . . . While the negative impact of loneliness cannot be denied, the treatment can be relatively simple. Part of treating loneliness is creating moments for genuine human interaction, which can be achieved on several levels. (ACGME, 2019)

Prevalence of Social Isolation and Loneliness

Understanding the prevalence of social isolation and loneliness is important in two ways. First, the population health impact of any risk factor is a function of the strength of its impact and its prevalence in a population. Second, whether a risk factor is becoming more or less prevalent is an indicator of whether its importance for population health is waxing or waning. However, it is very difficult to measure social isolation or loneliness in any population or to ascertain the degree of increase or decrease. A range of estimates have been made for the prevalence of social isolation and loneliness among different segments of the adult population in the United States. For example:

- Data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study found that 24 percent of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older in the United States were categorized as being socially isolated and 4 percent were severely socially isolated (Cudjoe et al., 2020);

- A 2012 study by Perissinotto and colleagues found that 43 percent of adults aged 60 and older reported feeling lonely. Furthermore, among those who reported at least one symptom of loneliness, 13 percent reported the symptom as occurring “often” (Perissinotto et al., 2012);

- A survey by the AARP Foundation found that more than one-third (35 percent) of adults aged 45 and older in the United States report feeling lonely (Anderson and Thayer, 2018);

- A 2018 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that “more than a fifth of adults [aged 18 and older] in the United States (22 percent) . . . say they often or always feel lonely, feel that they lack companionship, feel left out, or feel isolated from others” (DiJulio et al., 2018);

- A study by Hawkley and colleagues (2017) using data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project found that 19 percent of adults aged 62–91 report frequent loneliness (with an additional 29 percent reporting occasional loneliness); and

- A study by Cigna of adults aged 18 and older found that 46 percent reported “sometimes or always feeling alone” (Cigna/Ipsos, 2018).

Depending on how social isolation or loneliness is measured, the demographic trends contributing to it may include an increase in the number of people living alone, decreased marriage rates, higher rates of childlessness, or decreased community involvement (e.g., volunteerism, religious affiliation) (Holt-Lunstad, 2018b; Putnam, 2001). Social isolation and loneliness may occur unequally across age groups, including within the group of adults 50 years of age and older who are the focus of this report. Furthermore, the oldest adults may not be the most isolated or lonely. For example, the 2018 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 59 percent of the respondents who reported feeling lonely were under age 50 (DiJulio et al., 2018); the Cigna study found that adults aged 18–22 were the loneliest, and that loneliness decreased with age (Cigna/Ipsos, 2018); and a study by Hawkley and colleagues (2019) found that “loneliness decreased with age through the early 70s, after which it increased” (p. 1144).

Aside from looking for differences among various age segments of the adult population, several studies have examined whether there are variations in the prevalence of social isolation or loneliness among subsets of adults related to demographic factors such as socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, gender, educational status, employment status, and marital status. Several studies have found that those who report feeling lonely are more likely than others to report lower incomes and assets, having poorer health, and not being married (Anderson and Thayer, 2018; DiJulio et al., 2018; Hawkley et al., 2017). According to the study from Hawkley and colleagues (2017), “loneliness is not significantly more prevalent in the oldest old adults, nor in minority groups relative to whites, nor in women relative to men” (p. 6) and Anderson and Thayer (2018) found that individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (or queer) (LGBTQ) are more likely to say they are lonely. Cudjoe and colleagues (2020) found that “being unmarried, male, having low education, and low income were all independently associated with social isolation” (p. 107). They further found that “Black and Hispanic older adults had lower odds of social isolation compared with white older adults” (p. 107).

Differences in findings among many studies on the prevalence of social isolation and loneliness may be due, in part, to the challenges of defining and measuring social isolation and loneliness, including the use of different measures to assess different aspects of social isolation and loneliness in various groups that may differ by various demographic factors. Despite the variance in measurement, there are clearly a vast number of people who are socially isolated or lonely. Furthermore, the implications of these findings for physical or mental health, morbidity, and mortality underscore the urgency surrounding these issues and render them topics of highest concern to both public health and clinical health care.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

With support from the AARP Foundation, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) formed the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults in fall 2018. The committee’s charge essentially consisted of two parts. First, the committee was asked to examine how social isolation and loneliness affect health and quality of life in adults aged 50 and older, particularly among low-income, underserved, and vulnerable subpopulations. Second, the committee was charged to identify and recommend opportunities specifically for clinical settings of health care to help reduce the incidence and adverse health impacts of social isolation and loneliness (such as clinical tools and methodologies, professional education, and public awareness) and to examine avenues for translation and dissemination of information targeted to health care practitioners (see Box 1-1).

The committee was asked to focus on adults aged 50 and older. Social connections are considered to be a fundamental human need and thus are vital across the lifespan. The committee acknowledges the importance of social connection at all ages and recognizes that social processes at earlier ages influence the trajectory of risk as one ages. For example, there is evidence that social disruptions (e.g., adverse childhood experiences) at early ages can place individuals on a worse health trajectory (Anda et al., 2006; Uchino, 2009a). However, for the purposes of this study and the specific task, the committee did not examine the evidence base related to the health impacts on younger generations or interventions aimed at those populations. Furthermore, the committee notes that studies of both the health impacts of social isolation or loneliness and of potential interventions also often include different segments of the population over age 50, which can make comparisons across studies challenging.

While this report focuses on the specific role of the health care system (and the role of clinicians and clinical care in particular), the committee emphasizes that the health care system alone cannot solve all of the challenges related to social isolation and loneliness; rather, the health care system needs to connect with the

broader public health and social care communities. Furthermore, the committee recognizes that in the larger context of addressing social isolation and loneliness, the most effective interventions may not require the participation of the health care system. However, the committee argues that this does not mean that the health care system should not strive to help improve the health and well-being of those who suffer the adverse health impacts of social isolation and loneliness. In fact, health care providers may be in the best position to identify individuals who are at highest risk for social isolation or loneliness—individuals for whom the health care system may be their only point of contact with their broader community. In this way, the health care system can help those individuals to connect

with the most appropriate care, either inside or outside the health care system. Therefore, the health care system has the potential to be a critical component of a much larger solution. As noted by Lisa Marsh Ryerson, president of the AARP Foundation, in an open session of the committee’s first meeting:

We have been working in the space of social isolation and loneliness among older adults since 2010 and we have been working on advancing a variety of solutions as well as funding and examining the research. But for us this study fills an important research and recommendation gap because from our point of view we will not make measurable significant steps toward solving [social isolation and loneliness] unless we figure out the path for health care.

RELEVANT NATIONAL ACADEMIES REPORTS

The National Academies have produced many reports related to the social determinants of health, and several of them are directly relevant to this current study. The work, conclusions, and recommendations of the current committee reinforce, extend, and elaborate on the work, conclusions, and recommendations of prior National Academies committees. Box 1-2 provides some examples of previous National Academies work related to the work of this committee.

STUDY APPROACH

The Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults consisted of 15 members with expertise in bio-informatics, economics, epidemiology, geriatrics, health care, health care administration, medicine, nursing, psychiatry, psychology, public health, rural health, social work, and sociology. (See Appendix B for the biographies of the committee members.)

A variety of sources informed the committee’s work. The committee met in person five times, and during three of those meetings it held public sessions to obtain input from a broad range of relevant stakeholders, including the sponsor. (See Appendix A for the public meeting agendas with topics and speakers listed.) In addition, the committee conducted extensive literature reviews, reached out to a variety of public and private stakeholders, and commissioned one paper.

To address its charge, the committee set the following parameters

- Created a guiding framework that highlighted the role of the health care system

- Addressed relevant definitions

- Defined the scope of health care providers and settings

- Identified the populations at risk and age groups to be studied

- Considered the quality of the existing evidence base

Guiding Framework

Pursuant to its charge, the committee focused heavily on the clinical health care setting. This focus also seemed appropriate as clinical care is itself an aspect of, or an intervention related to, social connection. Clinical settings offer major opportunities for identifying problems related to social isolation and loneliness and for advancing interventions to alleviate these problems either within the clinical care setting itself or by mobilizing broader social and policy resources that may be needed for effective intervention.

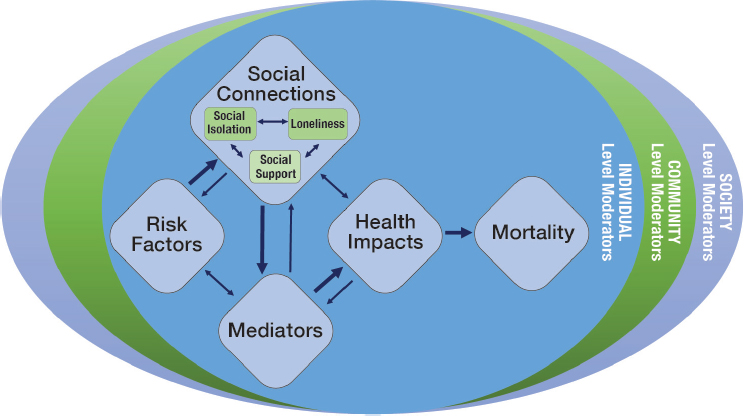

To guide its deliberations, the committee developed a conceptual framework to better understand the relationships among several aspects of social connections

and how they are embedded in the overarching public health focus on social determinants of health (see Figure 1-1). The framework in Figure 1-1 has a presumed causal flow (indicated by the thicker unidirectional arrows) from risk factors (for social connections and other variables in the framework) through social connections (i.e., social isolation and loneliness and other aspects of social connection such as social support, considered both independently and in relation to each other) to mediators (e.g., medical, biological, behavioral, social, and psychological pathways) through which social isolation or loneliness affect health outcomes and, potentially, mortality.

In this report and more generally, variables or boxes that intervene between a presumed causal factor and any subsequent variables or boxes that the cause is presumed to affect are termed mediators of that causal effect. Mediators (i.e., mechanisms or pathways) are the factors that help explain how social isolation or loneliness affects health outcomes. Most notably, variables in the box labeled pathways are hypothesized to mediate the effect of risk factors or social connections on health impacts, which in turn usually mediate these effects on mortality. Any of the variables in Figure 1-1, as well as other variables not specified there, may also act as moderators of any of the relationships between variables in the framework. Moderators are the factors that can influence the magnitude or direction of the effect of social isolation or loneliness on health. For example, the existence, nature, or strength of any empirical relationship hypothesized in Figure 1-1 may vary as a function of age, sex/gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic position, geographic location, or pre-existing health status.

Many of the relationships in the model are potentially bi-directional, as indicated by the thinner arrows. For example, social isolation and loneliness do causally affect health, but they, in turn, may also be affected by health status. That is, a chronic condition, for example, can be both a risk factor for or a consequence of social isolation or loneliness. The committee recognizes that separating discussions of health impacts (see Chapter 3) from risk and protective factors (see Chapter 4) can be challenging and confusing given that the same health condition is often discussed in both chapters, albeit for different reasons. Similarly, factors that mediate the relationship between social isolation/loneliness and health can also serve as moderators of those relationships. Therefore, the committee emphasizes

that the conceptual framework serves in part to highlight the complexity of all of these interrelationships. Individual elements of this framework will be discussed in more detail throughout the first half of this report. Specifically, the different aspects of social connections are discussed later in this chapter, mortality is discussed in Chapter 2, health impacts are discussed in Chapter 3, and risk (and protective) factors are discussed in Chapter 4. Chapter 5 discusses the potential role of many variables as mediators or moderators of the relationships among variables in the Figure 1-1 framework. All of these concepts and pathways offer opportunities for intervention (both directly and indirectly) by the health care system as a way of improving the ultimate health outcomes.

Finally, all of these relationships fit within a typical ecological model of health wherein factors contributing to social isolation and loneliness at the individual level are also potentially affected by the broader contextual factors at the levels of the community and society. Factors that influence social isolation and loneliness at the community level may include factors such as availability of transportation, broadband access, natural disasters, gentrification, and housing displacement. Factors that influence social isolation and loneliness at the society level may, for example, include racism, ageism, changes in family structure (e.g., lower rates of intergenerational living, higher rates of divorce and childlessness), trends in use of technology, and broader laws and policies that may affect social isolation and loneliness.

These influences at the level of the community and society are key to understanding risk for social isolation and loneliness and often have a reciprocal relationship with risk and protective factors at the individual level. For example, a key lifestyle feature of Blue Zones (geographic areas characterized by populations with low levels of chronic disease and long lifespans) is social connection. This may be in part due to how the overall social norms of these communities impact individual-level factors for social isolation and loneliness; Blue Zones are often characterized by living in proximity to one’s family, belonging to a faith-based community, and supporting healthy behaviors (e.g., healthy diets and exercise). These ideas are captured in the person-environment fit theory which “focuses on the interaction between the characteristics of the individual and the environment, whereby the individual not only influences his or her environment, but the environment also affects the individual” (Holmbeck et al., 2008, p. 33). This may be particularly important for individuals with disabilities for whom their social and physical environments influence participation, engagement, inclusion, and social relationships. Chapter 4 provides some insight for the contextual factors at the levels of the community and society, but an extensive discussion of all of these broader concepts and the bio-psycho-social model of health, is beyond the scope of this report.

This report focuses on social isolation, loneliness, and several related concepts, each of which contributes to health. However, because social isolation and loneliness are seldom included together in the same study as predictors of health outcomes, the evidence concerning the impact of each on health largely exists in parallel literature bases. Social isolation and loneliness need to continue to be

independently examined as potential predictors of the other related aspects of social connection as well as of health outcomes. More importantly, they need to be examined together (1) to discover potential pathways by which one may be operating through, or in combination with, the other in determining health outcomes; and (2) to better estimate the relative strength of their impacts on health outcomes and mortality.

Defining Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Related Aspects of Social Relationships

The broad, interdisciplinary scientific fields that together form the modern science of social relationships have used a variety of terms (e.g., social isolation, social connection, social networks, social integration, social support, social exclusion, social deprivation, social relationships, loneliness) to refer to empirical phenomena related to social relationships. Although there are important distinctions among these terms concerning what they describe or measure, they are often, incorrectly, used interchangeably. Some of the key terms that will be used throughout this report are presented in Box 1-3.

Social Isolation and Loneliness

Social isolation and loneliness represent distinct phenomena. Social isolation typically refers to the objective lack of (or limited) social contact with others, and it is marked by an individual having few social network ties, having infrequent social contact, or, potentially, living alone. Markers of social isolation objectively and quantitatively establish a dearth of social contact and network size. Loneliness refers to the perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely that “occurs when there is a significant mismatch or discrepancy between a person’s actual social relations and his or her needed or desired social relations” (Perlman and Peplau, 1998, p. 571). While loneliness is subjective, there are measurement tools that can help to quantify the degree of loneliness (see Chapter 6). Although those who lack social contact may feel lonely (Yildirim and Kocabiyik, 2010), social isolation and loneliness are often not highly correlated (Coyle and Dugan, 2012; Perissinotto and Covinsky, 2014). Thus, it is important to distinguish between social isolation and loneliness.

Related Aspects of Social Relationships

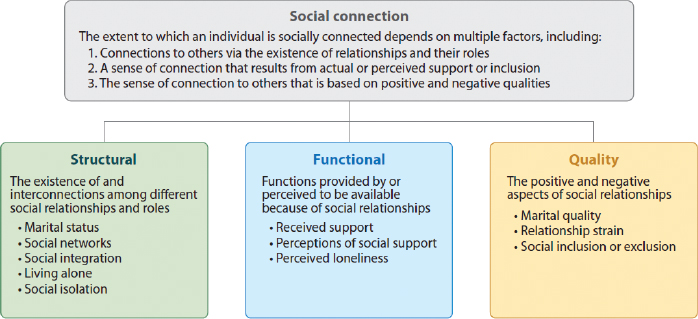

“Social relationships” is arguably the most common term for the connections and intersections among human beings, and it derives from and is employed in broader common usage. The term “social networks” has been used for some time as a similarly broad rubric for the connections among human beings and also other creatures, but it is also used more specifically to refer to the structure and way of analyzing relationship data (Scott, 1988). Berkman and Syme (1979) documented the powerful impact of social relationships on all-cause mortality and hence life expectancy, using the terms “social networks” and also “social integration” to denote the broad pattern of social relationships that they were examining; these terms are now part of the concept of social isolation. Beginning before the Berkman and Syme study and continuing over the succeeding four decades, the study of social relationships and health came to focus on social support. Social support is defined as the actual or perceived availability of resources (e.g., informational, tangible, emotional) from others, typically one’s social network (Cohen and Wills, 1985). While each of these terms used to describe social relationships have been linked to important health outcomes, they are not highly correlated, suggesting that each may influence health through different pathways (Cohen et al., 2000). Thus, the literature often refers to organizing themes—the structure, functions, and quality of our social relationships—that categorize the broader class of terms that have been termed social relationships by sociologists and epidemiologists or social connection by psychologists (Berkman et al., 2000; Holt-Lunstad, 2018b; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017; House et al., 1988). “Social connection” is an umbrella term that some have proposed using to encompass the different conceptual and measurement approaches represented

SOURCE: Holt-Lunstad, 2018a. Reproduced with permission from the Annual Review of Psychology, Volume 69 © 2018 by Annual Reviews, http://www.annualreviews.org.

in the scientific literature. (Holt-Lunstad, 2018a). According to Holt-Lunstad et al. (2017), social connection encompasses the variety of ways one can connect to others socially—through physical, behavioral, social–cognitive, and emotional channels. The extent to which an individual is socially connected takes a multifactorial approach, including (1) [structural aspects] connections to others via the existence of relationships and their roles; (2) [functional aspects] a sense of connection that results from actual or perceived support or inclusion; and (3) [qualitative aspects] the sense of connection to others that is based on positive and negative qualities. Figure 1-2 shows the three categories of indicators of social connection (i.e., structural, functional, and quality indicators) and provides examples of such indicators.

When considering risk factors and protective factors for social isolation and loneliness, having indicators of high social connection is typically considered protective while having indicators of low social connection is typically considered detrimental. Social isolation and loneliness are examples of low social connection, with social isolation being a structural aspect and loneliness a functional aspect. Some indicators of social connection are more stable than others, and the acute or chronic nature of these indicators will influence the degree of risk or protection.

The committee recognizes that the literature on social isolation and loneliness uses all of these terms. To describe the evidence base as accurately as possible, when the evidence does not differentiate among or combines several related terms, this report uses the term “social connection” to refer to the various structural, functional, and quality aspects of social relationships. This report uses

the specific terms “social isolation,” “loneliness,” or other terms when the data are specific to these terms.1

The Health Care System and Its Providers

For the purposes of this study, the committee examined the potential role of the formal health care system and settings where health care services are provided in reducing the impacts of social isolation and loneliness in older adults. The committee considered health care settings broadly to include not just hospital and professional offices, but also other community-based settings where clinical health care services are provided (e.g., homes, long-term care settings). In accordance with discussions with the sponsor in open session at the committee’s first meeting, the committee agreed to consider the settings of care broadly, but to focus on the provision of clinical care by qualified clinicians and health care workers (not including family caregivers). Therefore, the committee used the lens of the health care system itself on the role of health care professionals (e.g., nurses, physicians, social workers), direct care workers (e.g., home health aides, nurse aides, personal care aides), and others involved in the delivery of health care (e.g., community health workers, health care administrators, health information technology professionals). While the committee recognizes the vital importance of family caregivers (the family, friends, and others who provide care, sometimes called informal caregivers) to the delivery of health care as well as their role in mitigating the social isolation and loneliness of their family members, the committee and sponsor agreed that the focus for this study was to gain a comprehensive understanding of how social isolation and loneliness affect the individual and then explore the role of the formal health care system as described above.

The committee also limited its examination largely to literature from the United States. The committee based this approach not only on the likely differences among different countries that can affect social isolation and loneliness (e.g., societal norms, cultural expectations, and family structures), but also on the fact that the health care systems in other countries are markedly different from the U.S. health care system, and could make comparisons of clinical approaches quite challenging. However, the committee did review and include notable examples from other countries wherever relevant.

Finally, the committee considered general public health principles, including connection to the community and other public health partners, to be considered a part of comprehensive clinical care, especially given that the Statement of Task calls for the committee to consider “opportunities that can be incorporated into health care environments” (e.g., education, tools, public awareness). While the

___________________

1 While social integration can describe high social connection, low scores on measures of social integration (e.g., on the Berkman–Syme Social Network Index) are frequently used as an indication of social isolation. Thus, the term “social isolation” will also be used to represent these data.

committee’s ultimate recommendations are not all explicitly directed to health care professionals and other health care workers, the committee asserts that its recommendations are the ones that would be most helpful in reaching the ultimate goal of improving the role of individuals involved in clinical care in particular to help mitigate the negative health impacts of social isolation and loneliness.

Identifying Populations at Risk

Pursuant to its charge, the committee primarily focused its efforts on addressing the health and medical dimensions of loneliness and social isolation as they pertain to adults aged 50 and older. The committee’s work was necessarily limited by the available research on this population. Also in response to the charge, the committee sought to include relevant research pertaining to low-income, underserved, or vulnerable populations. To address these subpopulations of older adults, the committee included available research on specific populations as defined by race, geographic area (e.g., rural versus urban), immigration status, sexual orientation, and other characteristics. Although the research on many of these subpopulations is sparse, examinations of studies focusing on these subpopulations are included throughout the report as part of the evidentiary data for each topic area. A separate section specifically addressing particular subpopulations (i.e., gay, lesbian, and bisexual populations; minorities; immigrants; and victims of elder abuse) is included in Chapters 4 and 5. However, the committee emphasizes that the literature base specific to at-risk populations is quite sparse, and much more research is needed to determine the risks, impacts, and appropriate interventions for a variety of at-risk subpopulations.

Quality of Available Evidence

A significant and robust literature demonstrates the impact of social isolation and loneliness on health and well-being (see Chapters 2 and 3). However, the literature on effective interventions, particularly for the role of the health care system, is less robust. The existing studies of interventions vary in their terminology, measures, and measured outcomes. While this variability made comparing the studies and their overall conclusions quite challenging for the committee, the variability can also be a strength in the sense that it makes it possible to look for convergent validity (i.e., robustness of the empirical relationships among conceptual variables even in the face of some variation in measures and study designs; see Lykken, 1968) in establishing the effect of social isolation and loneliness on health and well-being.

The committee prioritized the available literature according to known principles of evidence-based health research intended to reduce the risk of bias affecting study conclusions (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Important factors include how participants are allocated to different types of interventions, the comparability of

study populations, controls for confounding factors, how outcomes are assessed, how representative the study group is of the older U.S. population, and the degree to which statistical analyses help reduce bias.

OVERVIEW OF THE COMMITTEE’S REPORT

The work of the current committee reinforces, extends, and elaborates on the work of prior National Academies committees. Chapter 2 examines the history and context of how social isolation in particular (and loneliness to a lesser extent) came to be recognized as a factor influencing mortality and how social support came to be recognized as a protective factor. Chapter 3 summarizes the evidence base for the impacts of social isolation and loneliness on morbidity and quality of life, while Chapter 4 summarizes the evidence base for the factors that put people at risk for social isolation and loneliness. Chapter 5 discusses the moderators and mediators of the relationships of social isolation and loneliness with health. Chapter 6 presents a brief overview of the tools used for measurement and assessment in research settings as well as of the use of information technology to identify individuals at risk for social isolation or loneliness. Chapter 7 discusses the role of the health care system specifically in addressing social isolation and loneliness. Chapter 8 considers the importance of education and training of the general public and the health care workforce, particularly in raising awareness of the health impacts of social isolation and loneliness. Chapter 9 presents an overview of interventions for social isolation and loneliness, focusing on approaches that are most applicable to health care providers and settings. Chapter 10 reflects on the principles of dissemination and implementation in order to explore avenues for translating research into practice. The citations for all chapters have been merged into a single reference list that follows Chapter 10. Appendix A provides the agendas of the committee’s open sessions, including the topics and speakers. Appendix B contains the biographical sketches of the committee members and project staff.

This page intentionally left blank.