2

Evaluating the Evidence for the Impacts of Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Other Aspects of Social Connection on Mortality

Strong social relationships are essential for a good life. The consequences of neglecting this fact become especially apparent in old age. Thus it is urgent that more attention be given to social isolation as a potential killer.

Developing the current understanding of the health impacts of social isolation and loneliness as well as other aspects of social connection has been part of a larger development regarding the importance of social determinants of health (i.e., the recognition that biomedical treatments are actually not, on average, the most significant determinants of the health outcomes of individuals). A major endpoint of this historical trend has been the scientific identification of social isolation as a major risk factor for human mortality, morbidity, and well-being. Loneliness and other aspects of social connection are also emerging potential risk factors for mortality.

This chapter considers the evidence for social isolation, loneliness, and other aspects of social connection as potentially causal risk factors for mortality, while Chapter 3 will do the same for morbidity and well-being. (Unless otherwise specified, mortality in this chapter is defined as all-cause mortality.) Both chapters consider the current evidence for social isolation, loneliness, and other aspects of social connection being risk factors for health and well-being.

The development of any area of scientific inquiry is rarely a simple, logical linear process. Knowing how we have gotten to where we are in any area of science is essential to understanding how and why we know what we do and what we do not. It can also clarify issues such as concepts and their definitions (see Chapter 1), their empirical measurement (see Chapter 6), and the nature of the scientific

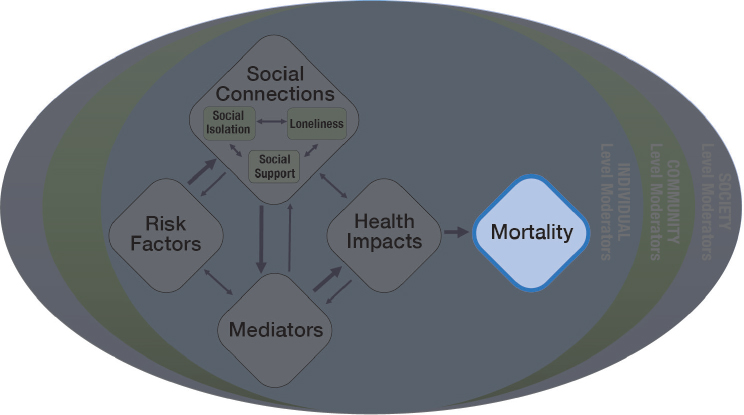

evidence regarding putatively causal relationships. Thus, this chapter begins with an overview of how social factors (e.g., the social determinants of health), including major social disparities and inequalities, have come to be recognized as major determinants of or risk factors for health and especially how and why social isolation and loneliness have come to be particularly pivotal at this point in time. This chapter represents the portion of the committee’s guiding framework related to mortality (see Figure 2-1). Given the complexity of the terminology used in relation to social isolation and loneliness, a reminder of key definitions is provided in Box 2-1.

A HISTORY OF UNDERSTANDING THE CONTRIBUTORS TO HUMAN HEALTH

For most of human history human life was, in the famous words of Thomas Hobbes, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Hobbes, 1965, p. 97). The life expectancy of human individuals and populations never exceeded 30–35 years of age until the beginning of the 18th century, and it was not until the end of the first half of the 20th century that life expectancy increased to about 65 years of age, after which it increased to almost 80 years by the end of the 20th century. The period since the 18th century saw the development of modern biomedical health science as well as such public health advances as the decline in infectious disease between the mid-18th and mid-20th centuries and the decline in rates of smoking in the last half of the 20th century. Thus, it seemed logical to

attribute the dramatic rise of human life expectancy to the application of biomedical science, clinical medicine, and biomedically based public health. Such an attribution continues to dominate much thinking about health policy even to the present day, though its validity has been increasingly challenged, and most health researchers now agree that clinical medicine, public health, and social changes all contributed to this increase in life expectancy (see House, 2015, especially Chapter 4; McGinnis et al., 2002; McKeown, 1976, 1979, 1988; Szreter, 1988, 1997, 2000). This growing appreciation for the impact of public health and social changes on health has given rise to a new appreciation of non-medical (e.g., environmental, health behavior, social and community, psychological, and socioeconomic) factors in health, most often referred to as social determinants of health.

The Role of Public Health

The era of the industrial revolution of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries saw the development of a public health approach to ensure “the conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 1988, p. 1). Immunizations, improvements in drinking water and sanitation, increasing food safety, and the pharmacological treatment of infectious diseases resulted in reductions or eradication of many

acute illnesses (CDC, 2001). These public health approaches led to an “epidemiological transition”—a shift from acute to chronic illnesses as the leading causes of death (Omran, 1971). As a result, “public health has shifted its primary focus from addressing infectious disease to tackling chronic disease” (IOM, 2012, p. 3). Understanding the impacts of the physical, chemical, and biological environments on health led to the recognition of a broader set of determinants of health that is beyond clinical medicine, though still largely within the biomedical framework.

The identification of cigarette smoking and other negative health behaviors as major risk factors for mortality and morbidity was pivotal to the movement toward a conception of the broader social determinants of health. The recognition of the danger of tobacco was considered one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century (CDC, 2001). However, in spite of compelling evidence linking cigarette smoking to lung cancer and other causes of death, it took almost a quarter century to move from the strong scientific evidence to an effective comprehensive public health policy and then another quarter century to see major health improvements. The case of cigarette smoking and health gave rise to broader science, policy, and practice regarding the impacts of other health-related behaviors such as excessive consumption of alcohol, overeating, and the lack of physical activity (Berkman and Breslow, 1983). Increasingly, these behaviors joined cigarette smoking as major targets of intervention in both health care and broader public health policy (HHS, 2001, 2010).

Social Disparities in Health

As the understanding of the importance of social determinants of health grew in the last decades of the 20th century, there was also a renewed recognition of the disparities in health by socioeconomic position, race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and various combinations thereof. Most notably, in the late 1970s and early 1980s a commission in the United Kingdom found that differences in mortality by occupational status had not declined at all and perhaps had even grown in the quarter century after the National Health Service had presumably equalized access to health services (Black, 1982). Others found similar trends of differences in mortality by education and income in the United States (Pappas et al., 1993) and Canada (Wilkins et al., 1989). The World Health Organization (WHO) has focused attention on the social injustices that underlie inequities and inequalities in longevity and quality of life. A 2008 report of WHO’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health stated:

These inequities in health, avoidable health inequalities, arise because of the circumstances in which people grow, live, work, and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. The conditions in which people live and die are, in turn, shaped by political, social, and economic forces. (CSDH, 2008)

The identification of social disparities in the prevalence of any or all risk factors for health or in their impact became another major component of the growing science, policy, and practice regarding the social determinants of health.

DISCOVERING SOCIAL CONNECTIONS AS A DETERMINANT OF HEALTH AND LONGEVITY

Despite a long history of suggestions that social connections were integral to human health and well-being, a systematic investigation of social relationships, especially in relation to health, did not emerge until several decades after research on the social determinants of health had begun following World War II. In the mid-1970s, two physician social epidemiologists, John Cassel and Sidney Cobb, independently linked social support to health (Cassel, 1976; Cobb, 1976). Cassel and Cobb each reviewed a wide range of evidence from humans and animals showing that social connections were protective of health, especially in the face of biological and psychosocial risk factors for disease, most notably psychosocial stress, and both emphasized the ability of social support to buffer or moderate the adverse effects of such risk factors to health across a wide range of health outcomes. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, multiple researchers had identified various issues concerning the research on social support and health, including (1) what the causal associations between social support and health were, (2) “whether social relationships and supports [only or mainly] buffered the impact of stress on health or had more direct effects,” and (3) how consequential the effects of social relationships on health really were (House et al., 1988, p. 541).

A number of researchers began to explore existing prospective longitudinal cohort studies for evidence of the long-term impacts of social connection on mortality that would be analogous to the evidence that had been used to identify other major biomedical and behavioral risk factors for mortality. Researchers focused on measures of the presence, extent, and types of social ties or relationships (e.g., marital status, contacts with friends and relatives, membership in—or at least attendance at services or meetings of—religious congregations or other formal and informal voluntary organizations or groups). These types of measures at baseline (individually and, especially, collectively) proved to be highly predictive of mortality, even after controlling for a large number of other predictors of mortality.

In the seminal study of this type, Berkman and Syme (1979) analyzed four measures collected in the Alameda County Study: (1) marital status, (2) frequency of contacts with other friends and relatives, (3) membership and frequency of participation in voluntary organizations, and (4) frequency of attendance at religious services. They found that all four of these factors predicted mortality over the succeeding 9 years in multivariate analyses that controlled for self-reports of physical health, socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity,

and the use of preventive health services. A “social network index” combining all four factors produced a relative risk ratio for all-cause mortality of about 2.0 for the socially isolated versus the more socially integrated—that is, socially isolated individuals were twice as likely to die in any given year as those who were more socially integrated (Berkman and Syme, 1979). A similar analysis in the Tecumseh Community Health Study that added biomedical baseline measures (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol, respiratory function, electrocardiograms) to a similar set of self-reported controls at baseline obtained similar results (House et al., 1982). Further replicating studies came from the United States (Schoenbach et al., 1986) and Europe (Orth-Gomer and Johnson, 1987; Tibblin et al., 1986; Welin et al., 1985), and in 1988 House and colleagues summarized these data and other experimental and quasi-experimental evidence from animals and humans as follows:

[S]ocial relationships, or the relative lack thereof, constitute a major risk factor for health—rivaling the effect of well established health risk factors such as cigarette smoking, blood pressure, blood lipids, obesity, and physical activity. (House et al., 1988, p. 541)

The conclusions of House et al. (1988) have remained valid over the succeeding three decades, and research on the mortality impacts of lack of social relationships or connections, increasingly called “social isolation,” have continued. Furthermore, the number of studies has expanded tremendously. The remainder of this chapter summarizes the current state of the evidence in terms of overall magnitude of the effect on mortality of different aspects of social connection (e.g., social isolation, loneliness, social support) and why these may be causal effects.

THE CURRENT STATE OF THE EVIDENCE ON IMPACTS OF SOCIAL ISOLATION, LONELINESS, AND SOCIAL SUPPORT ON MORTALITY

As described in Chapter 1, the scientific evidence concerning social isolation and loneliness is based on a variety of different related conceptual and measurement approaches that all characterize related aspects of social relationships. To describe this evidence as accurately as possible, when the evidence does not differentiate among several related terms or perhaps combines them this report uses the term “social connection” (or “connectedness”) as an umbrella term to refer to the structural, functional, and quality aspects of social relationships (Holt-Lunstad, 2018a,b; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017). Social isolation and loneliness are common indicators of low social connection, while social support is a common indicator of high social connection. (See Chapter 1 for additional indicators of high and low social connection.) This report uses the specific terms “social isolation,” “loneliness,” and “social support” only when the data are specific to these terms.

The following sections summarize the evidence from meta-analyses and systematic reviews that synthesize the overall evidence for the mortality impacts of social isolation, loneliness, and social support across many studies as well as data from important individual studies.

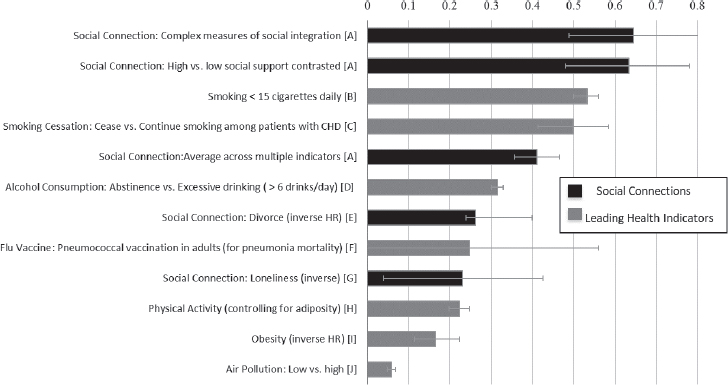

Evidence Establishing Social Isolation as a Major Risk Factor for Mortality

A comprehensive meta-analysis by Holt-Lunstad and colleagues (2010) has been widely cited and influential in refocusing attention on the impacts of social connections on mortality. This analysis included 148 prospective studies that measured the structural (e.g., social integration,1 network size, marital status, living alone), functional (e.g., perceived support, received support, perceived loneliness), or combined aspects (e.g., complex social integration) of social relationships and that followed participants over time (an average of 7.5 years) to determine the predictive association with mortality. This analysis, which examined studies with data from more than 300,000 participants, found that having a stronger social connection was associated with 50 percent greater odds of survival. Furthermore, these findings were consistent across age, gender, cause of death, and country of origin. Since this publication, several additional prospective studies and meta-analyses have replicated these findings (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2012; Rico-Uribe et al., 2018; Shor and Roelfs, 2015; Tanskanen and Anttila, 2016). Figure 2-2 provides their estimates, as well as more recent estimates, of the odds of decreased mortality of various indicators of social connection and other major risk factors for health.

The strongest results come from studies that used complex measures of social integration (which essentially correspond to the absence of social isolation). One example of such a measure is the Berkman–Syme Social Network Index, which is now included in several ongoing national surveys and recommended for inclusion in electronic medical records by a prior Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee (IOM, 2014). Low scores on this measure are often used as an indicator of social isolation. The measure has been and can be varied modestly across epidemiologic studies and could also be adapted slightly for clinical use. (See Chapters 6 and 7 for more on the use of the Berkman–Syme Social Network Index and other measures in clinical settings.)

In sum, more than four decades of research has produced robust evidence that lacking social connections has been associated with significantly increased risk for premature mortality—and this is strongest among measures of social isolation. Furthermore, in spite of a variety of challenges in the definitions and

___________________

1 While social integration can describe high social connection, low scores on measures of social integration (e.g., the Berkman–Syme Social Network Index) are frequently used to measure social isolation. Thus, the term social isolation will also be used to represent these data.

NOTES: Odds (InOR) or Hazards (InHR). Effect size of zero indicates no effect. The effect sizes were estimated from meta-analyses: A = Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; B = Shavelle et al., 2008; C = Critchley and Capewell, 2003; D = Holman et al., 1996; E = Shor et al., 2012; F = Fine et al., 1994; G = Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; H = Katzmarzyk et al., 2003; I = Flegal et al., 2013; J = Schwartz, 1994.

SOURCE: Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017.

subsequent measurement of both social isolation and loneliness, there is some evidence that the magnitude of the effect on mortality risk may be comparable to or greater than other well-established risk factors such as smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity (which also have their own challenges in terms of determining causality). Importantly, this effect is independent of age and initial health status, which argues against reverse causality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Rico-Uribe et al., 2018; Shor and Roelfs, 2015). (See later in this chapter for a discussion of causality using Bradford Hill criteria.)

Evidence on Loneliness as a Risk Factor for Mortality, Considered Independently and in Relation to Social Isolation

In addition to the compelling evidence regarding social isolation as a major risk factor for mortality, evidence is emerging on the association between mortality and loneliness. Attention to loneliness grew because of two main factors: (1) the development of the concept and measurement of loneliness as a cognitive/emotional personality state or trait, and (2) the development of social neuroscience. Russell and colleagues (1980) developed the concept and the still-dominant measure of loneliness, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, while a related

scale was developed in the Netherlands (de Jong Gierveld and Kamphuis, 1985). (See Chapter 6 for more on the measurement of social isolation and loneliness in research.) Many researchers have explored a causal link between loneliness and health, and, as a result, a growing number of predictive associations of loneliness with mortality have been found (e.g., Drageset et al., 2013; Luo and Waite, 2014; Perissinotto et al., 2012). In a recent meta-analysis focused exclusively on the association between loneliness and mortality, which included 35 prospective studies with 77,220 participants, the researchers concluded that loneliness significantly increases the risk for all-cause mortality—by 22 percent—independent of depression (Rico-Uribe et al., 2018). The authors did note that the variability in the instruments used to measure loneliness among the studies may be a limitation of interpreting the results. However, the finding was consistent with a previous meta-analysis that found that loneliness was associated with a 26 percent increased risk for premature mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Thus the predictive effect of loneliness on mortality (independent of depression) appears to be replicable, if smaller than that for social isolation.

Evidence on Social Isolation and Loneliness Considered Together

While substantial research has documented the risk of premature mortality posed by both social isolation and loneliness, most studies have examined these factors separately. And because only a handful of studies have examined both loneliness and social isolation in the same sample, there is currently limited ability to explore and compare their effects on mortality as independent or joint factors or to explore the degree to which loneliness is more a mediator of the health impacts of social isolation. Among studies that have examined both social isolation and loneliness in the same sample, most have tested which had the most important unique contribution—in essence, pitting social isolation and loneliness against each other. The strongest study that contained good measures of both social isolation and loneliness was done in a large nationally representative sample in the United Kingdom, which found that both social isolation and loneliness were associated with mortality when considered independently and with limited control variables. The effect of loneliness though was not independent of demographic factors such as age or health problems and did not increase the risk associated with social isolation. Therefore the subjective experience of loneliness, which may be the psychological manifestation of social isolation, appears not to be the primary mechanism explaining the association between social isolation and mortality in this study (Steptoe et al., 2013).

Similarly, the UK Biobank cohort study, which included 479,054 men and women, found that social isolation, but not loneliness,2 predicted increased mortality

___________________

2 In this study the authors used a two-item scale to measure loneliness (i.e., “Do you often feel lonely?” and “How often are you able to confide in someone close to you?”).

in those with a history of acute myocardial infarction (Hakulinen et al., 2018). Thus, it appears that social isolation has an independent influence on the risk for mortality, which remains significant even when adjusting for loneliness, but the same is not true for loneliness.

Ong et al. (2016) reached similar conclusions in a review focused specifically on older adults that considered broader indicators of health as well as mortality:

Although there is growing interest in studying the prevalence and detrimental effects of loneliness in later life . . . [q]uestions remain about whether the associations between loneliness and health reflect the effects of loneliness, the effects of objective social isolation, or the effects of unmeasured variables. Thus longitudinal and experimental studies addressing the direct, indirect [mediating], and moderating effects of social isolation and loneliness on health are urgently needed. (Ong et al., 2016, pp. 448–449)

A 20-year prospective study with a nationally representative sample of more than 4,800 middle-aged and older adults in Germany suggests there may be synergistic effects of social isolation and loneliness (Beller and Wagner, 2018a). The evidence indicates that the greater the social isolation, the larger the effect of loneliness on mortality and that the greater the loneliness, the larger the effect of social isolation (Beller and Wagner, 2018a,b).

To summarize, there is a large literature of studies that examine social isolation and loneliness separately as predictors of premature mortality; however, to date only five published studies have examined both social isolation and loneliness within the same sample. These five studies are all large population-based studies, but none were conducted within the United States. While these studies confirm their respective effect on risk for premature mortality, they also begin to elucidate more complex findings when considering their joint contributions. When social isolation and loneliness are considered together, social isolation has remained a robust predictor of mortality, but loneliness appears more tenuous.

Evidence Regarding Social Support and Mortality

Social support is one of the three major components of social connection, and it has been extensively studied in relation to health. Among the 148 studies included in the meta-analysis by Holt-Lunstad and colleagues (2010) on mortality risk, roughly half included measures of social support, and its role as a major independent risk factor for mortality has substantial support. However, the term “social support” has many different specific meanings and measures. For example, support may be instrumental, emotional, or informational; it may also be received, perceived3 (as helpful or available if needed), or provided

___________________

3 Perceived social support is conceptually similar to loneliness.

to others. When the effect of social relationships on mortality was broken down by measurement approach, perceived support and received support were found to have different effects. Perceived social support significantly predicted 35 percent increased odds of survival, which is stronger than the effect of loneliness (see Figure 2-2). However, the effect of received support, which was in the moderate range, was non-significant (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Uchino (2009a,b) and Uchino et al. (2011) have discussed multiple possible reasons why received support may be less predictive than perceived support (or other indicators of social connection).

Research on social support as a construct has also been distinct from the literature on social isolation, although the two are intimately intertwined. Thus, we do not know the degree to which these may overlap (e.g., those who are isolated or lonely may perceive low social support). As with loneliness, more research in this area is needed.

Evidence of the Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on Specific Causes of Mortality

While all-cause mortality provides the most compelling evidence of the impact of social isolation and potentially loneliness, these two factors are also necessarily associated with the elevation of certain specific major causes of death. For example, individuals who are socially isolated or lonely and have a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke have been shown to be at increased risk of death (Hakulinen et al., 2018). Among nearly 15,000 patients with chronic heart disease, living alone was related to a higher risk of cardiovascular death, while being married (compared to being widowed) was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular death (Hagström et al., 2018). Among heart failure patients, those reporting high levels of loneliness had a nearly four times greater risk of death than patients who self-reported low levels of loneliness (Manemann et al., 2018). (See Chapter 3 for a discussion of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.)

A FURTHER NOTE ON SOCIAL ISOLATION, AND SOCIAL CONNECTION MORE GENERALLY, AS A POTENTIAL CAUSAL RISK FOR MORTALITY

Substantial evidence supports an association between social connection (across varied measurement approaches) and both better health and a reduced risk for mortality; there is also substantial evidence for an association between a lack of social connection (especially social isolation) and poorer health and an increased risk of mortality. However, some may ask whether, in the absence of randomized control trials, this can truly be said to be a causal association. Causality is difficult to determine experimentally in this case because one cannot randomly assign individuals to be socially isolated. Furthermore, as discussed previously,

there is uncertainty related to the different definitions of and measures for various aspects of social connection and so measurement uncertainties can make it difficult to determine causality with certainty. Table 2-1 outlines the Bradford Hill criteria, a framework for determining causality in epidemiology studies, and applies them to social isolation, including whether the criteria have been met, and

TABLE 2-1 Applying the Bradford Hill Criteria to Consider the Causal Influence of Social Isolation on Mortality

| Guideline | Description of Guideline | Evidence | Evidence That the Guideline Has Been Satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Is there experimental evidence? | Experimental evidence in animals shows that isolation increases mortality. Humans randomly assigned to loneliness induction, exclusion, or support conditions show different health-relevant physiological responses. | |

| Strength | Is the effect size greater than combined effect of confounders? | Overall magnitude of effect (risk ratio) is about 2.0, which is strong and comparable to or greater than other accepted risk factors. | |

| Temporality | Does the cause occur before the effect? (temporal precedence) | Prospective evidence establishes direction of effect. Poor social connection precedes mortality and poor health. | |

| Biological gradient | Is there a dose–response effect? | Animal and human evidence demonstrates a dose–response effect. | |

| Biological plausibility | Are there plausible mechanisms of action? | Established biological, behavioral, and cognitive pathways (see Chapter 5 for details). | |

| Coherence | Is the evidence coherent with (does not contradict) other known mechanisms? | Coheres with animal and human studies showing that increasing care support for children and neonates improves their health. | |

| Replicability | Can the effect be repeated across multiple studies? | Many studies in 2010 meta-analysis plus several more now have replicated these findings. | |

| Similarity | Do similar studies show consistent results? | Across the varied measurement approaches of social isolation and other aspects of social connection, there is converging evidence. |

SOURCE: Adapted from Howick et al., 2019.

also provides a summary of the evidence that satisfies each criterion. By adapting the Bradford Hill criteria for social connections in general, evidence is found to support a potential causal link between social isolation and mortality.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

- Social isolation has been associated with a significantly increased risk of premature mortality from all causes.

- There is some evidence that the magnitude of the effect of social isolation on mortality risk may be comparable to or greater than other well-established risk factors such as smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity.

- While there is evidence of a significant association between loneliness and mortality, existing evidence does not yet approach the cumulative weight of evidence of the association between social isolation and mortality. Further research is needed to establish the strength and robustness of the predictive association of loneliness with mortality in relation to social isolation and to clarify how social isolation and loneliness relate to and operate with each other (as well as other aspects of social connection, such as social support).

NEXT STEPS AND RECOMMENDATION

In today’s society social isolation and loneliness are as prevalent as many other well-established risk factors for health, yet limited resources and attention have been paid to better understanding social isolation and loneliness and their individual and collective impacts on health. To enhance the role of the health care sector in addressing the impacts of social isolation and loneliness among older adults, the committee identifies the following goal:

GOAL: Develop a more robust evidence base for effective assessment, prevention, and intervention strategies for social isolation and loneliness.

Achieving this goal will require increasing funding for basic research on social isolation and loneliness. The body of evidence for the association of social connection (particularly of social isolation) with all-cause mortality is strong, and the magnitude of this association may rival that of other risk factors that are widely recognized and acted upon by the public health and health care systems (e.g., smoking, obesity, physical inactivity). However, given this evidence, current funding for social isolation and loneliness is not adequate. The committee concludes that in particular, further research is needed to establish the strength and robustness of the predictive association of loneliness with mortality in relation to social isolation and to clarify how social isolation and loneliness relate to and

operate with each other in order to inform effective clinical interventions. Therefore, the committee recommends:

RECOMMENDATION 2-1: Major funders of health research, including the government (e.g., the National Institutes of Health, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute), foundations, and large health plans should fund research on social isolation and loneliness at levels that reflect their associations with mortality.