Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand health information, services, and skills needed to make informed health decisions and take action (IOM, 2004). It is a critical skill for engaging in healthy behaviors to reduce disease risk and improve health outcomes across the continuum of cancer care. However, estimates suggest that more than one-third of the U.S. adult population has low health literacy, and nearly half of all patients with cancer have difficulty understanding information about their disease or treatment (Heckinger et al., 2004; Kutner et al., 2006). Low health literacy among patients with cancer is associated with poor health and treatment outcomes, including lower adherence to treatment protocols (Rust et al., 2015; Turkoglu et al., 2018), higher rates of missed appointments (Knolhoff et al., 2016), and an increased risk of hospitalization (Cartwright et al., 2017). Low health literacy can also impede informed decision making, especially as cancer care becomes increasingly complex and as patients and their families take more active roles in treatment decisions.

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of the individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

To examine opportunities to improve communication across the cancer care continuum, the National Cancer Policy Forum collaborated with the Roundtable on Health Literacy to host a workshop, Health Literacy and Communication Strategies in Oncology, July 15–16, 2019, in Washington, DC. The workshop convened diverse participants, including patients, patient advocates, clinicians, and researchers, as well as representatives of health care organizations, academic medical centers, insurers, and federal agencies. The following topics were explored:

- Strategies to enhance communication among diverse populations with varying levels of health literacy and to promote culturally competent communication;

- Opportunities to improve patient–clinician communication across the cancer care continuum;

- Media and public health strategies to build public trust and convey accurate information about cancer;

- Research strategies to promote health literacy and communication;

- Opportunities for health care organizations and insurers to improve communication and support health literacy; and

- Stakeholder perspectives and priorities for communication and health literacy in oncology.

This workshop proceedings highlights suggestions from individual participants regarding ways to improve communication in cancer care and better support individuals across the range of health literacy abilities. These suggestions are discussed throughout the proceedings and are summarized in Box 1. Appendix A includes the Statement of Task for the workshop. The agenda is provided in Appendix B. Speakers’ presentations and the webcast have been archived online.2

HEALTH LITERACY AND COMMUNICATION

Many workshop speakers discussed the challenges of achieving effective communication in cancer care, and specifically the challenges in meeting the diverse health literacy needs of individuals and ensuring clinicians and public health practitioners engage in culturally competent communication. Karen Basen-Engquist, professor of behavioral science at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, noted that the National Action Plan to Improve

___________________

2 See Health Literacy and Communications Strategies in Oncology: A Workshop at http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Disease/NCPF/2019-JULY-15.aspx (accessed September 4, 2019).

Health Literacy outlines two key principles (ODPHP, 2010): (1) All people have the right to health information that enables them to make informed decisions, and (2) health services should be delivered in ways that are understandable to patients and that improve health, longevity, and quality of life.

She added that achieving these principles can be particularly challenging in oncology because of the complexity of cancer care. Michael Paasche-Orlow, professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, added that patients with cancer often face difficult decisions that are dependent on an individual’s clinical and social context. He noted that the key to promoting health literacy and communication is to identify strategies to empower patients and family members to help them make informed health decisions.

Leveraging Media for Cancer Education and Prevention

Elmer Huerta, director of the Cancer Preventorium at Medstar Washington Hospital Center’s Washington Cancer Institute, discussed media strategies to improve cancer education among Spanish-speaking populations. He described his formative experiences in a Peruvian hospital in the 1980s, where he observed that many patients had a limited understanding of their health but were well informed about activities such as sports or television programs with broad media coverage. This motivated him to develop and implement cancer prevention and early detection education programs through the use of broadly accessible media and to create clinics focused on disease prevention.

Huerta said that it is important to understand cancer epidemiology in context; the geographic distribution of cancer depends not only on tumor biology, but also on external factors such as the resources available in the community. “We should not concentrate only on the study of the tumor, but also on the person with the tumor,” Huerta said, adding that patients’ fears, poverty, fatalism, lack of insurance, false beliefs, and lack of information about cancer are just as important for disease etiology as genetic susceptibility. The challenge in addressing many of these factors is conveying the importance of cancer prevention. Thus, Huerta created a culturally relevant, media-based community program based on four principles: (1) consistent and predictable communication that occurs on a regular schedule; (2) comprehensive health education that addresses diverse health topics, not just cancer; (3) use of multiple media channels available to the community, including radio, Twitter, and Facebook; and (4) the building of community trust by ensuring that messages and programming are free from commercial interests.

To complement this media-based cancer education program, Huerta founded a clinic, the Cancer Preventorium, to provide chronic disease prevention, early detection, and patient education services. The Cancer Preventorium has two primary goals: to manage risk factors for chronic diseases, and to

identify and provide early treatment for asymptomatic conditions such as cancer, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Huerta noted that the preventorium model includes community outreach, the clinic itself, and a patient navigation program. He added that this model has been adopted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as part of the curriculum for the Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program.3

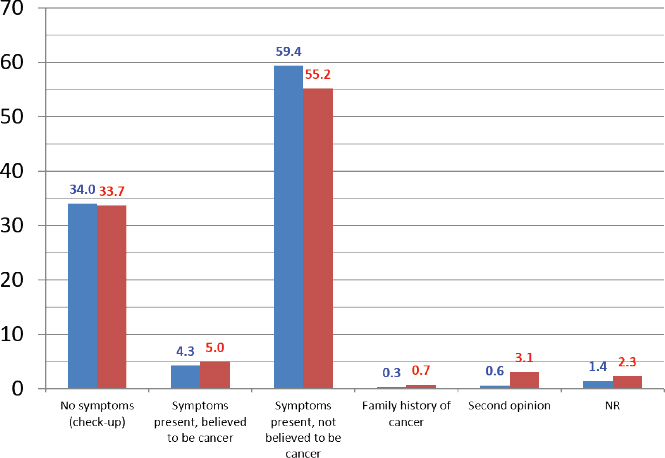

Since the Cancer Preventorium opened in July 1994, more than 37,000 people—30 percent men, 70 percent women, and approximately 95 percent foreign-born Hispanics—have been seen at the facility. Two-thirds of these patients have less than a high school level of education, and the majority do not have health insurance. For individuals who require follow-up care but lack health insurance, the Cancer Preventorium makes referrals to local community clinics for treatment. Huerta noted that the most common ways people learn about the Cancer Preventorium are through the radio or from friends and family. Approximately one-third of the clinic’s patients have no symptoms, and more than half present with symptoms they do not believe are related to cancer (see Figure 1). Huerta noted that approximately 90 percent of the clinic’s patients come for preventive care.

The Role of Culture in Cancer Care and Research

Marjorie Kagawa Singer, research professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, Fielding School of Public Health, discussed culturally informed clinical care, best practices for communicating with multicultural populations, and the importance of incorporating culture in health research. Kagawa Singer said that several factors could contribute to miscommunication, including low health literacy, anxiety about speaking with a doctor, differing expectations of communication etiquette, and language barriers. She stressed that miscommunication impedes progress in reducing health disparities (IOM, 2012).

Culture in Cancer Care and Communication

Kagawa Singer noted a major challenge in achieving effective communication among culturally diverse populations: the majority of health psychology researchers and participants in health psychology research are from WEIRD countries—Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. However,

___________________

3 See Course: Principles and Practice of Cancer Prevention and Control at https://cpfp.cancer.gov/summer-curriculum/course-principles-and-practices-cancer-prevention-and-control (accessed October 25, 2019).

NOTES: This graph shows a total of 774 patients; 45.2 percent are male (blue) and 54.8 percent are female (red). NR = no reply.

SOURCE: Huerta presentation, July 15, 2019.

these WEIRD individuals represent only 12 percent of the world’s population (Henrich et al., 2010a,b). “For those of you who are researchers, every theory you use has likely been standardized on primarily non-Hispanic white populations, and that is not [representative of] the United States. . . . We are a multicultural society with a monocultural approach to health care that denies culture as a complex determinant for health disparities,” said Kagawa Singer. She noted that demographic trends in the United States will continue to exacerbate this challenge, as minority populations will soon constitute the largest share of the overall population (Colby and Ortman, 2014).

Kagawa Singer said that the health care community should recognize that there are fundamental differences in cultural constructs and should view cultural differences as assets and sources of strength for patients and their families. Many cultures emphasize interdependence, community welfare, and group consensus over individuality, and acknowledge that suffering is a fact of life. In contrast, cultural constructs in the United States often reflect independence, individualism, autonomy, and happiness. A major challenge in the delivery of culturally competent communication is reconfiguring the health care system and clinicians to respect these cultural differences and foster trust between clinicians and patients, even if they have distinct cultural values and

backgrounds that may initially conflict with the health care staff and agency structure. Kagawa Singer stated that integrating culture into health care helps the patient and family understand their situation and collaboratively create goals for care with their clinicians.

Ivis Sampayo, senior director of programs at SHARE,4 also described the benefits of integrating cultural competence in clinical care and cancer communication. She noted that her organization has the capability to help women who speak any of 19 languages; offers webinars and onsite programs in English, Spanish, and Japanese; provides outreach programs in English and Spanish; and has peer ambassadors to African American and Latino communities. She described LatinaSHARE’s novella program, a communication tool designed to overcome cultural and language barriers by presenting information on breast cancer detection, diagnosis, treatment, and survival using a fictional narrative in a culturally popular comic book format. Since the program’s development in 2010, approximately 150,000 copies of the novella have been distributed. Sampayo noted that, through the use of accessible media such as comic books, even children and teenagers can learn about cancer prevention and can help serve as educators for their families.

Culture in Cancer Research

Kagawa Singer discussed the application of culture in health research. She defined “culture” as a “dynamic, multilayered and multidimensional system comprised of shared beliefs, values, lifestyles, ecologic, social, political, and technical resources and constraints that dynamically changes and adapts to circumstances that its members use [it] to provide safety, security, and meaning for and of life” (Kagawa Singer et al., 2015). She noted that despite the central role of culture in explaining behavior, the construct of culture is woefully understudied, poorly defined, and rarely integrated beyond superficial steps in both research and practice. She said that culture is often operationalized in terms of ethnicity or language, but cautioned against this approach, because neither fully captures the construct and because these are unique constructs that need to be addressed individually in health research.

Instead, Kagawa Singer stressed the need for measurement frameworks that fully integrate salient aspects of each culture with health literacy. These frameworks enable clinicians and researchers to more accurately identify which aspects of culture may affect health outcomes. To address this need, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research funded research to develop a cultural framework for health research

___________________

4 See the SHARE homepage at https://www.sharecancersupport.org (accessed October 25, 2019).

(Kagawa Singer et al., 2015). This framework calls for researchers to answer six questions before designing an intervention with culturally diverse populations:

- Is the rationale for the inclusion of culture clearly articulated in the problem statement?

- Has a definition of culture for the clinical or research objective(s) been articulated?

- Are select theoretical and cultural constructs known?

- Is there correspondence between salient theoretical and cultural constructs?

- Is there a conceptual framework that specifies how salient constructs affect the health issue of focus? (E.g., have independent variables, moderating effects, and mediating effects been identified?)

- Are there cross-culturally equivalent existing measures?

COMMUNICATION ACROSS THE CANCER CARE CONTINUUM

Many workshop participants discussed strategies and best practices to improve patient–clinician communication and meet patients’ health literacy needs across the continuum of cancer care.

Prevention and Screening

Cathy Meade, senior member in the Division of Population Science, Health Outcomes, and Behavior at the Moffitt Cancer Center, discussed the need for effective cancer prevention communication. She noted that almost half of cancer deaths are linked to preventable causes, including tobacco use, obesity, exposure to ultraviolet light, and vaccine-preventable infections (ACS, 2019). She added that prevention science has matured in recent decades, and the World Health Organization has described cancer prevention as the most cost-effective, long-term strategy for cancer control: “National policies and programs should be implemented to raise awareness, to reduce exposure to cancer risk factors and to ensure that people are provided with the information and support they need to adopt healthy lifestyles” (WHO, 2019).

Meade said the cancer community needs to convey the transformative potential of cancer prevention to the general public, noting that adopting a healthy lifestyle can reduce the risk of cancer and other chronic diseases, and improve treatment outcomes and prevent cancer recurrence. However, she said it can be challenging for many people to interpret and apply information about cancer prevention and risk reduction. Adding to the complexity of the challenge is the growing diversity of the U.S. population, which will require

improved emphasis on culture and literacy to inform and advance health equity (Collins and Blige, 2016; Meade, 2005).

Meade suggested that a significant obstacle to communication about cancer prevention is that members of the public may not understand what prevention entails. She described her experience conducting focus groups to develop patient materials about cancer. She found that many participants did not understand the term “prevention.” Meade recounted that one participant asked if prevention was like getting a checkup for a car, which reinforced to Meade the importance of likening cancer prevention activities to common and familiar points of reference. She said that striving for a shared understanding is the ultimate goal of cancer communication.

Meade said it is important to consider the development, delivery, and distribution of messages about cancer prevention. She said materials should be relatable, engaging, actionable, and written for the appropriate level of literacy (Meade et al., 2018). At the same time, messages need to be accurate and scientifically sound. Rigorous formative work—including focus groups, usability testing, and community–academic partnerships—can help to achieve these goals. Meade encouraged researchers to solicit and incorporate feedback on messages from the target audience. Other facets of effective health communication include good presentation, attention-capturing messaging, and the use of multiple modes of delivery to inform diverse members of the population about cancer prevention.

Meade proposed three strategies to achieve effective communication and promote health literacy for cancer prevention: (1) advocate at the national level for policies that enhance access, insurance coverage, and reimbursement for cancer prevention; (2) strengthen the evidence base for the role of health literacy through research that advances the engagement of marginalized, underrepresented, and underserved communities in cancer prevention; and (3) advocate for the creation of a national council or network that engages diverse stakeholders in establishing guidelines, procedures, and tools for communicating evidence-based information about cancer risk, prevention, detection, and treatment to patients, families, and communities.

Cancer Treatment

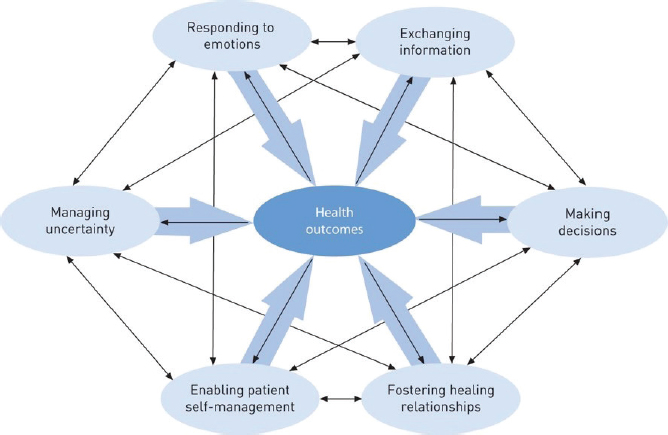

Anthony Back, professor of oncology at the University of Washington School of Medicine and co-director of the Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence, stressed that effective patient–clinician communication is critical, especially as cancer care becomes more complex. Back noted that NCI has identified six domains of patient-centered communication that affect health outcomes (see Figure 2): exchanging information, making decisions, fostering healing relationships, enabling patient self-management, managing

SOURCES: Back presentation, July 15, 2019; Epstein and Street, 2007.

uncertainty, and responding to emotions (Epstein and Street, 2007). Back suggested that all clinicians involved in caring for patients with cancer build skills in these domains.

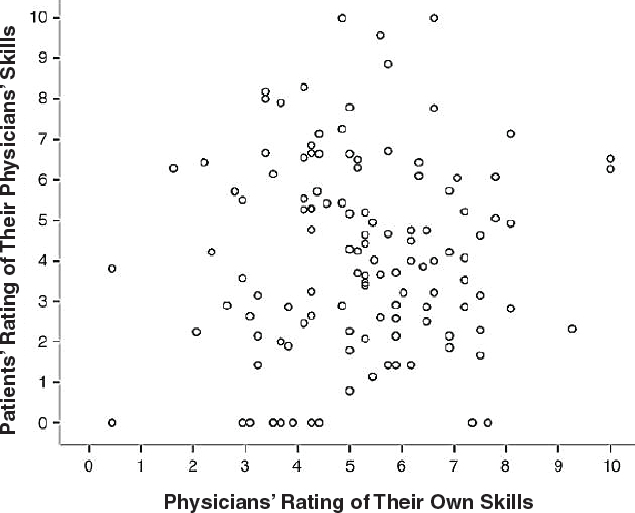

Back noted that clinicians are often poor judges of their communication skills, with a misalignment between patients’ reporting of their clinicians’ communication abilities and clinicians’ self-reporting (Dickson et al., 2012) (see Figure 3). In a national physician survey, 99 percent of practicing physicians agreed that having conversations about advance care planning and goals of care are “important” or “very important,” but only 14 percent reported holding and documenting these conversations (PUR/C, 2016). Physicians reported various reasons for not holding these conversations, including a lack of formal training, inadequate time, and uncertainty about how to broach these challenging conversations with patients.

Back said that supporting communication competencies among clinicians is critical for achieving high-quality cancer care (Bernacki et al., 2019; Paladino et al., 2019): “Having these conversations improves patient outcomes,” said Back. He added that these conversations are associated with a higher likelihood of goal-concordant care, higher patient-rated care experiences, lower likelihood of aggressive care near the end of life, increased length of hospice care, and less depression and anxiety among bereaved family members (Curtis et al., 2018; Detering et al., 2010; Gade et al., 2008; Mack et al., 2010, 2012; Wright et al., 2008). Additionally, patients are more trusting of clinicians

SOURCES: Back presentation, July 15, 2019; Dickson et al., 2012.

with strong communication skills, which improves patient care (Tulsky et al., 2011). “This is not about just being a nice doctor,” said Back. “It is really about a skill set that every oncology clinician should have.”

Back noted that communication is a learned skill (Langewitz et al., 1998) and that appropriate training can help clinicians be more empathetic, ask more questions, and actively recognize patients’ values (Back et al., 2007). What is missing, said Back, is the ability of every practicing clinician to receive such training. To address this, Back founded VitalTalk.org,5 a nonprofit organization that uses an evidence-based learning model to teach clinicians how to more effectively discuss serious illness with patients (Arnold et al., 2017). In 3 years, VitalTalk has trained more than 500 faculty members, who have subsequently held more than 600 workshops that enable clinicians to practice newly learned skills.

Back identified several strategies to improve clinician communication skills. First, develop better cognitive tools and protocols for communication that invite two-way, person-centered exchange (Back et al., 2009). One such

___________________

5 See the VitalTalk homepage at https://www.vitaltalk.org (accessed October 25, 2019).

tool is the REMAP framework, which teaches clinicians to reframe situations, expect emotions, map important values, align with patients and families, and plan treatment to uphold values (Childers et al., 2017). Additional strategies include promoting non-punitive learning cultures that reinforce deliberate, positive communication practice, and fostering peer learning to generate a network of informal mentoring.

Back emphasized that the tools to improve clinician communication are ready to scale, but policies are needed to support their implementation. He suggested widely disseminating evidence-based communication training programs and embedding clinician-educators within health systems to facilitate skills acquisition and maintenance (Back et al., 2019; Gilligan et al., 2017). He added that payers could create incentives for clinicians and health care organizations to build communication skills and that performance metrics could help to foster accountability (Back et al., 2019).

Mandi Pratt-Chapman, associate center director for patient-centered initiatives and health equity at The George Washington University Cancer Center, agreed that effective communication is essential for facilitating informed and shared decision making. Pratt-Chapman suggested using plain language and avoiding medical jargon (Schwartzberg et al., 2007). She also supported providing patients with specific advice, such as “increase your physical activity by five minutes three times a week,” rather than using ambiguous language, such as “get more exercise.” She added that using the teach-back method can help confirm that patients understand the information they receive.6 Pratt-Chapman also described the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Ask Me 3 technique,7 which helps focus patient–clinician conversations on identifying primary health concerns, discussing interventions to address them, and ensuring that patients understand the plans for their care.

Deborah Collyar, founder and president of Patient Advocates in Research, emphasized that all patients and families, no matter their level of education, experience shock when they receive a cancer diagnosis, which can impede effective communication. Collyar suggested that decision-making tools and templates be developed for clinicians to use during cancer care, particularly during enrollment for clinical trials. She added that the NCI Clinical Trials Network could employ an iterative process of designing and testing these materials, in partnership with patient communities.

___________________

6 In the teach-back method, clinicians ask patients to repeat medical information in their own words to ensure comprehension.

7 Additional information is available at http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Ask-Me-3-Good-Questions-for-Your-Good-Health.aspx (accessed August 21, 2019).

Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer

Gwendolyn Quinn, Livia Wan M.D. Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology in the Department of Population Health and the Center for Medical Ethics at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine, discussed patient–clinician communication issues among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Every year, approximately 70,000 people ages 15 to 39—collectively referred to as adolescents and young adults (AYA)—are diagnosed with cancer (NCI, 2018). The AYA category also includes adult survivors of pediatric cancer, who often suffer lifelong effects from cancer and its treatment.8 Quinn noted that the AYA population has numerous psychosocial and health concerns after a cancer diagnosis, such as treatment side effects, finances, fertility, self-esteem, and career and education prospects.

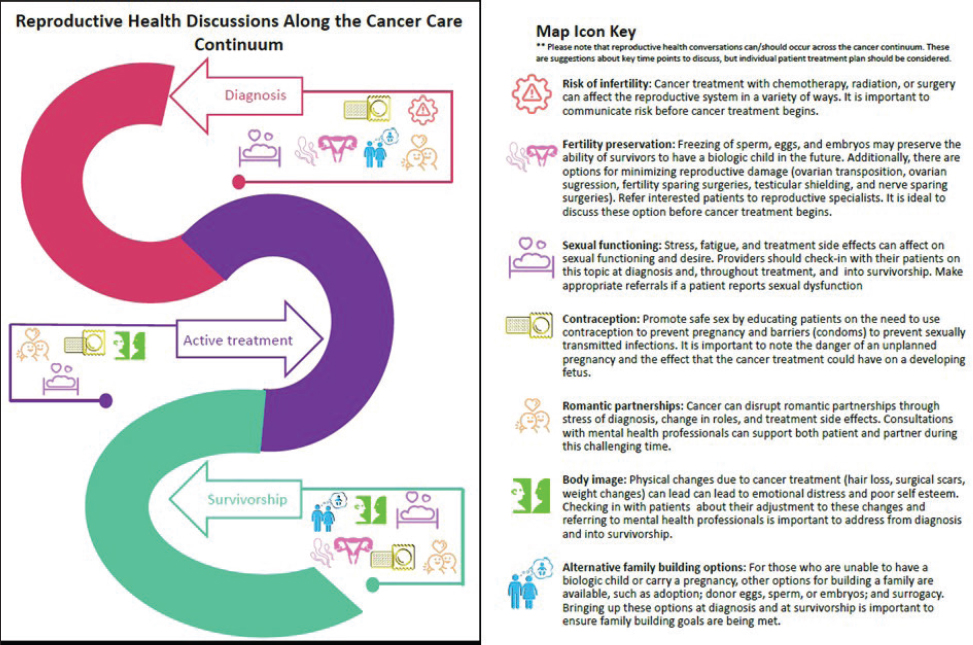

Guidelines from several cancer advocacy and research organizations describe the importance of conveying information about reproductive health to adolescents and young adults with cancer (Coccia et al., 2018; Oktay et al., 2018). Quinn noted that reproductive health concerns in oncology extend beyond infertility and fertility preservation to include romantic partnering, friendships, body image, sexuality, sexual identity and orientation, contraception, and psychosexual adjustment. These concerns are relevant at various times throughout the continuum of cancer care (see Figure 4). However, cancer clinicians often do not broach these topics with AYA patients. In a national study of oncologists, Quinn and her colleagues found that the primary reasons oncologists do not talk about reproductive health or infertility with their AYA patients is that they do not have time and were not trained to do so (King et al., 2008a,b; Vadaparampil et al., 2007). She noted that clinicians were willing to accept responsibility for engaging AYA patients in conversations about reproductive health, but only if trained and empowered to do so (Quinn and Vadaparampil, 2009; Quinn et al., 2007, 2008).

The diverse developmental stages in AYA populations present an additional challenge in patient–clinician discussions about reproductive health. “The way you would talk about potential loss of fertility and sexual function to a 15-year-old who may never have had a sexual experience would be very different than how you would talk to a 35-year-old who has been in a partnered relationship for a time,” explained Quinn. As a result, it can be challenging for health care professionals to determine appropriate language and strategies to mitigate patients’ discomfort with the topic. Quinn noted that the heteronormativity of most patient education materials is also a concern when

___________________

8 The unique communication and health literacy needs of children were not a focus of this workshop, but discussions throughout this proceedings may help inform strategies for pediatric populations.

SOURCE: Quinn presentation, July 15, 2019.

discussing reproductive health with AYAs. In response, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients with cancer are starting to create their own support and information networks.

To address patient–clinician communication challenges among AYA patients with cancer, Quinn suggested that institutional policies have a key role in establishing guidelines for appropriate communication. She suggested that health care organizations caring for AYA patients with cancer develop a readiness checklist that includes

- Referral pathways to reproductive specialists and mental health professionals,

- A documentation system,

- Communication training for clinicians,

- Psychological support for reproductive health services and access to financial support if reproductive health services are elected,

- Psychosocial support services, and

- Patient education materials.

Survivorship Care

Frank Penedo, associate director for cancer survivorship and translational behavioral sciences at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine’s Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, discussed challenges in communicating health information among the growing population of cancer survivors.9 He noted that as of 2019, there were more than 16.9 million Americans living with a history of cancer, a number projected to reach more than 26.1 million by 2040 (Bluethmann et al., 2016). Cancer survivors face ongoing chronic and debilitating health and psychosocial challenges, such as adverse effects from cancer and its treatment, comorbidities, functional limitations, and complex care needs, as well as life disruptions and financial burdens. Penedo said that approximately 30 percent of cancer survivors experience clinically elevated levels of psychological distress, particularly anxiety and depression (Mehnert et al., 2014).

Penedo noted that the report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition found insufficient emphasis on the needs of cancer survivors (IOM, 2003, 2006; NASEM, 2017, 2018b). Penedo highlighted essential focus areas of high-quality survivorship care: addressing lifestyle factors and comorbidities, ensuring continuity of care, and conducting ongoing symptom monitoring and management. Penedo stressed that survivorship care plans

___________________

9 The term “cancer survivor” has been defined as “an individual affected by cancer, from the time of diagnosis through the balance of his or her life.” See https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics/definitions.html (accessed September 20, 2019).

(SCPs)10 are a key tool for ensuring effective patient–clinician communication in survivorship care. He noted that creating and discussing SCPs engages patients as active partners in their ongoing care. SCPs also promote continuity in the transition between oncology and primary care (IOM, 2006). According to guidelines from the American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer, survivorship care plans should contain both a summary of the patient’s disease and treatment (e.g., clinicians’ contact information, diagnosis and stage, description of treatment, and description of ongoing toxicities) and a detailed plan for follow-up care (e.g., the need for ongoing therapy, schedule of upcoming visits and tests, symptoms of recurrence, and psychosocial concerns) (Mayer et al., 2014). Although the Commission on Cancer has recently revised their accreditation requirements to recommend but not require SCPs, Penedo said that these documents can help promote continuity of care by effectively communicating clinical care information that may otherwise not be available to the patient and the patient’s other clinicians.

Penedo discussed the importance of patient-centered communication in survivorship care, including responding to emotions, managing uncertainty, exchanging information, and enabling self-management (Economou and Reb, 2017) (see Table 1). He added that clinicians should incorporate patient-reported outcomes in their assessments, noting that patient-reported outcomes in survivorship care can enhance communication between patients and clinicians, facilitate shared decision making, and help patients assess their progress over time. Collyar agreed, adding that patient-reported outcomes can also help measure important aspects of patient experience that extend beyond disease symptomatology.

Penedo described the design and implementation of a program to monitor survivors’ patient-reported outcomes via the patient portal at the University of Miami Health System. Patients are asked to respond to questions that capture their experiences during and after care encounters. Many of the questions are based on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System,11 a set of short, well-validated, computerized questions that can be used to evaluate and monitor key domains, including pain, fatigue, physical functioning, and emotional well-being, as well as practical needs, such as transportation, child care, and nutrition. Some responses trigger automatic alerts to social work or nursing staff.

___________________

10 Survivorship care plans include a comprehensive summary of oncology care and a follow-up plan, and serve to facilitate communication between patients and their care teams after discharge from cancer treatment (IOM, 2006).

11 Additional information is available at http://www.healthmeasures.net/exploremeasurement-systems/promis (accessed August 12, 2019).

TABLE 1 Patient-Centered Communication Strategies for Cancer Survivors

| Function | Domains |

|---|---|

| Responding to emotions |

|

| Managing uncertainty |

|

| Exchanging information |

|

| Enabling self-management |

|

SOURCES: Penedo presentation, July 15, 2019; Economou and Reb, 2017.

Palliative and End-of-Life Care

Nina O’Connor, chief of palliative care for the University of Pennsylvania Health System and chief medical officer for Penn Medicine Hospice, defined “palliative care” as specialized medical care for patients with serious illnesses, such as cancer, that provides expert pain and symptom management, emotional support and assistance with coping, advance care planning, and end-of-life discussions (Ferrell et al., 2018). Palliative care is provided in partnership with the patient’s care team and is available any time during cancer care, regardless of the other treatments a patient receives (see Figure 5).

O’Connor noted that a key challenge in patient–clinician communication about palliative care is countering the inaccurate belief that palliative care is

| Function |

|---|

|

|

|

|

available only to patients who forego active treatment. Clinicians may also find it difficult to broach the topic of palliative care and advance care planning without training, because they fear it may take away a patient’s hope. However, “there are many ways we can teach health care providers to talk about palliative care while maintaining hope,” said O’Connor. She said that few clinicians have received formal training in discussing palliative care and advance care planning (Horowitz et al., 2014), and time pressures can create barriers to these discussions.

O’Connor added that there is a national workforce shortage of palliative and hospice care physicians (Lupu, 2010). O’Connor said that to help address this challenge, all oncology clinicians should be trained in basic palliative care

SOURCES: O’Connor presentation, July 15, 2019; Center to Advance Palliative Care.

skills, with select clinicians receiving additional training from palliative care specialists so they can serve as local resources. This would enable the limited pool of available palliative care specialists to consult on complex cases and train other clinicians. “Only through a model like this are we actually going to be able to meet all of the patients’ needs,” she said. O’Connor also spoke in favor of the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act12—a bill that has passed in the U.S. House of Representatives and is pending in the U.S. Senate—that would create training centers to expand the palliative care workforce. It would also fund research on best practices for palliative care and a public awareness campaign about palliative care.

To ensure that every University of Pennsylvania Health System patient with serious illness at has a conversation about advance care planning, O’Connor and her colleagues employ a strategy developed by Ariadne Labs and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and tested at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.13 This strategy provides a set of tools to help clinicians, patients, and families engage in productive conversations about serious illness care. It also includes a 3-hour clinician training course and coaching for 1 additional month, as well as various system tools to assess program implementation. O’Connor stated that patients who have had these conversations at University of Pennsylvania Health System cancer centers have provided positive feedback. “Patients really want to have these conversations,” said O’Connor. “They are waiting for these conversations, and they feel much closer to their clinician when we have these conversations.”

___________________

12 See H.R. 1676—Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act at https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1676 (accessed October 25, 2019).

13 See Serious Illness Care Program Study at https://www.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/03/SI-DFCI-Outcomes-fact-sheet-2019-03-12c.pdf (accessed October 25, 2019).

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES TO BUILD PUBLIC TRUST AND COUNTER INACCURATE INFORMATION

Many workshop participants discussed strategies for improving health literacy among the general public and building trust with the public health community. Workshop speakers also discussed the emergence of misinformation about cancer and the associated public health threat, and suggested opportunities for various stakeholders to counter inaccurate information.

Addressing Online Health Misinformation

Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou, program director in the Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch at NCI, defined “health misinformation” as “a health-related claim of fact that is currently false due to a lack of scientific evidence” (Chou et al., 2018). She said that addressing the high prevalence of false information on social media is key to engaging the public in effective communication about cancer. Although social media platforms can offer social support and an accessible venue for peer-to-peer sharing of health information, she said they can also serve as an echo chamber that enables the rapid spread of misinformation. Chou added that dissemination of misinformation is facilitated by the viral nature of social media, the vulnerability of patients and their families, low public trust in expertise, and the limited health literacy skills of individuals.

Chou discussed opportunities to assess and proactively address cancer-related health misinformation (Chou et al., 2018; Southwell et al., 2019). She said that the first step is to identify the consequences of exposure to misinformation, as well as the level of exposure that produces adverse effects. Next, she said, the cancer community needs to increase surveillance on health communication and misinformation. “We need to do a better job collecting longitudinal, spatial, and network information [and] thinking about not just explicit forms of misinformation, but implied and implicit misinformation.” She added that the public health community, in partnership with trusted community leaders, also needs to conduct outreach efforts to build public trust, raise awareness, and promote education about important health-related topics. Finally, she said, new interventions are needed that address and mitigate misinformation and that are respectful of the identities, emotions, and values of the intended audiences.

Chou described two NCI initiatives to promote research on public communication and strategies to address misinformation in cancer. The first is a funding opportunity to develop innovative approaches to studying cancer communication across the continuum of cancer care in the evolving media

environment.14 The second is a collaboration with the American Journal of Public Health to produce a special issue on health misinformation on social media,15 including articles characterizing misinformation, describing the health consequences of exposure to misinformation, and proposing strategies to mitigate the effects and limit the spread of misinformation. Chou noted that there are clear opportunities for health care organizations, community partners, and communication practitioners to assess and address misinformation about cancer and reduce its adverse effects on public health. She suggested that the public health community partner with social media platforms to promote the dissemination of accurate health information.

James Hamblin, writer and senior editor at The Atlantic, suggested that the public health community participate actively in social media to disseminate credible information and counter misinformation. “There are so many different platforms out there and so many different styles of communication. . . . [T]here is something for everyone,” he said. “It requires a little dedication and commitment to figuring out how that platform works, what your target audience is, and what you are trying to do, whether it is activate, inform, or just generally engage.” Hamblin noted that social media provides health care professionals and scientists the opportunity to reach large portions of the public, and to disseminate health information directly and in plain language so that messaging is relevant and broadly accessible.

Opportunities for Local and State Governments

Shalewa Noel-Thomas, chief of the Cancer and Chronic Disease Bureau at the District of Columbia (DC) Department of Health, noted three important health literacy concerns: health insurance benefits literacy, health care system literacy, and health behavior literacy. Health insurance benefits literacy enables patients to navigate insurance options, identify covered services, and understand their financial responsibilities for health care. Noel-Thomas noted that health insurance literacy can be challenging even for individuals with otherwise high levels of literacy. Health systems literacy requires understanding different types of care (e.g., primary care versus specialty care), how to access care, and how to navigate the health care system. Health behavior literacy considers health education and health promotion, and requires understanding

___________________

14 See Department of Health and Human Services: Part 1. Overview Information at https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/par-16-249.html (accessed September 23, 2019).

15 See APHA Call for Proposals: Special Issues about Health Misinformation on Social Media at https://ajph.aphapublications.org/pb-assets/downloads/CFP_HealthMisinformation_Full.pdf (accessed September 23, 2019).

principles of disease management and the association between health behaviors and health outcomes.

Noel-Thomas described how the DC Department of Health approaches health education interventions for populations with varying levels of health literacy. For those with high health literacy, the department focuses on activities such as distributing brochures or engaging in mass media campaigns (e.g., an ongoing smoking cessation campaign that places advertisements on the sides of buses). For individuals with moderate health literacy, a more involved approach is needed, such as one-on-one counseling or health education classes. The DC Department of Health’s Thriving and Surviving workshop series, for example, includes seven weekly 2.5-hour sessions on self-management and communication skills led by cancer survivors or caregivers. For those with low health literacy, she said that more intensive services are warranted, including involvement of community health workers, as well as patient navigation for people diagnosed with cancer.

Noel-Thomas noted that she and her colleagues have assessed health literacy among local residents using mixed methods approaches that include web-based surveys and focus groups. These assessments found that DC residents’ health insurance coverage is among the highest in the nation and that residents have high self-efficacy for identifying a clinician to address a particular medical need.16 Participants were very active in chronic disease self-management, sought care at regular intervals, and were engaged in informed decision making. The evaluation also identified various challenges, such as long wait times for appointments. Respondents also reported fragmentation of care, particularly a lack of communication among clinicians. Navigating the health system was also difficult for many DC residents, and residents voiced frustration with the way health information was conveyed to them. Finally, residents reported low health literacy regarding their medications.

Noel-Thomas said that the recommendations from this evaluation included increasing the use of technology for clinician communication; using telehealth more extensively to reduce appointment wait times, particularly for specialty care; and increasing patient assistance programs, such as patient navigation. Other recommendations included reducing administrative barriers (e.g., the process for obtaining a referral) and providing a digital health management tool to enable patients to ask questions of their peers.

___________________

16 “Self-efficacy” refers to “an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments.” See Teaching Tip Sheet: Self-Efficacy at https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/education/self-efficacy (accessed September 24, 2019).

Conveying Accurate and Accessible Information to the Public

Richard Wender, chief cancer control officer at the American Cancer Society (ACS), spoke about ACS’s role in communicating accurate and accessible information about cancer. He noted that members of the public, as well as professional organizations, expect ACS to serve as a trusted source for information about cancer; to convene and provide leadership in the fields of cancer research and policy; to embrace health equity; and to meet the needs of patients, caregivers, and the general public. Wender said that ACS views its mission as a “360 degree effort” across a variety of activities and venues (e.g., online chat, call centers, personal guidance, and scientific articles) to meet the diverse needs of individuals and organizations. He added that Cancer.org, ACS’s website, is the most accessed cancer website in the world, logging approximately 120 million visits in 2018.

Wender stated that all information provided by ACS needs to be evidence based and comprehensive, and presented in a way that is easily understood. ACS is also attentive to acknowledging when there is insufficient evidence to make definitive statements. Everyone at the organization, he added, is responsible for providing information. He noted that ACS’s content development team includes two oncologists, nurses, and social workers, and also draws on subject matter experts throughout the organization. All of the organization’s materials for the public are available in both English and Spanish.

Wender said that ACS is very aware of its reputation as a trusted organization that has been in existence for more than 100 years. He stressed that the organization needs to re-earn that trust every day by communicating accurate, scientifically grounded information: “When you are facing marketing pressures and fundraising pressures, having that anchor of what we believe scientifically is truth is very important.” He noted that the organization is perceived by the public as a definitive source for cancer information, and multiple departments are involved in maintaining the accuracy of the information it disseminates. He added that there are substantial challenges to this responsibility, including challenges in addressing questions of causality in cancer etiology and in the use of ACS information in a variety of contexts (e.g., in controversial policy debates, lawsuits, or media coverage).

ACS responds to both national and local media inquiries daily, Wender noted, and the organization strives to engage experts throughout the organization rather than responding with prepared statements. “Anybody can read an official position on cancer.org, but our experts add value. They try to communicate with the media in ways that can be understood and synthesized,” Wender said. He noted that the organization will respond to almost any question on almost any topic, though he also understands that in the current media landscape, ACS’s efforts to convey science-based information may not

always be conveyed appropriately. “The reporter is not the one who writes the headlines, which often highlight where controversy is, and that is a challenge,” said Wender.

Community Engagement and Health Communication

Lisa Fitzpatrick, founder of Grapevine Health and lecturer at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at The George Washington University, started to think about opportunities to engage the public with effective health communication when she was asked by an audience member at a presentation how to find answers to health questions outside of clinician office visits. Years later, Fitzpatrick secured a small grant from The Commonwealth Fund to evaluate the potential for broadly disseminating accessible health information through digital media. The study found that mobile phone ownership was nearly ubiquitous, but few used digital health tools. However, there was interest, if such tools could be designed in an engaging way.

The study also found that participants were more trusting of health information received from family and friends than health information received from clinicians. Through a series of focus groups, she found that the primary driver for this mistrust is that clinicians speak in a manner that is not easily understood. She said that low trust in clinicians contributes to avoidance of the health care system, even among individuals who need medical care.

Fitzpatrick noted that another key lesson she has learned through her engagement with community members is that building trust requires showing up and engaging people where they live. “We cannot keep expecting them to come to us,” said Fitzpatrick, adding that people often find health care buildings cold and unfriendly and that staff can sometimes be disrespectful. By moving out of the clinic and engaging people where they live, she and her colleagues have identified and begun to counteract many common misconceptions about cancer. She said this community-based outreach is critical to building trust and improving the health of individuals and communities.

Fitzpatrick noted that it is crucial to train each person within a health organization on strategies to address the health literacy needs of patients and their families. This training needs to emphasize the importance of speaking in a language that community members can understand, with the goal of demystifying cancer treatment and research. Fitzpatrick also suggested that organizations assess barriers to the use of social media and consider opportunities to use social media to disseminate health messages. Health care organizations also need to ask for patient and community member input to build trusting relationships.

High-Quality Health Journalism

Ivan Oransky, vice president of the editorial department at Medscape, distinguished writer in residence at New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, and co-founder of Retraction Watch, described the current state of health communication in news media. He stressed that health journalism is often undersupported in media outlets, which can contribute to oversimplified or inaccurate health news content. A study in 2008 that evaluated the content of 500 health-related news media items found that many did not meet several criteria for quality reporting (Schwitzer, 2008) (see Table 2). These deficiencies are important, he explained, because a large proportion of the population seeks health information from online media; in a 2010 poll surveying 1,066 adults, 88 percent reported looking for health information online (Harris Poll, 2010).

Oransky said that only 8 percent of health reporters have a background in biology, and as few as 3 percent are medical doctors (Viswanath et al., 2008). He added that many health reporters work at specialized media outlets, and few are well resourced. A small number of reporters are responsible for producing large volumes of content. Barriers to quality journalism include a lack of time and knowledge, competition for audience, complex terminology,

TABLE 2 Quality of Reporting in Health Journalism: Results from a Sample of 500 News Stories

| Quality Criteria (Did the Story Adequately . . . ?) | % Satisfactory |

|---|---|

| Discuss costs | 23% |

| Quantify benefits | 28% |

| Quantify harms | 33% |

| Discuss existing alternative options | 38% |

| Seek independent sources and explore conflicts of interests in sources | 56% |

| Avoid disease-mongering | 70% |

| Discuss quality of the evidence | 35% |

| Establish the true novelty of the approach | 85% |

| Discuss the availability of the new approach | 70% |

| Go beyond a news release | 65% |

SOURCES: Oransky presentation, July 15, 2019; Schwitzer G (2008) How Do US journalists cover treatments, tests, products, and procedures? An Evaluation of 500 Stories. PLoS Med 5(5): e95. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050095.

difficulty in identifying and using reputable sources and independent experts, and editors who were not trained in critical appraisal of medical news and commercialism (Larsson et al., 2003).

Oransky noted that the prevalence of misleading health information can also be attributed in part to public relations communications within academic medical centers. For example, one study found that in a random sample of press releases from academic medical centers, 74 percent of the releases based solely on research conducted in test tubes or on animal models made explicit claims regarding relevance to human health (Woloshin et al., 2009). Of the 95 press releases about clinical research, 23 percent omitted the study size and 34 percent did not quantify effect size. Another study found that 40 percent of academic medical center press releases contained exaggerated advice, one-third contained exaggerated causal claims, and 36 percent contained exaggerated inferences to human health from animal research (Sumner et al., 2014). This study also found that exaggeration in press releases was strongly correlated with overstatement in resulting news stories.

To address these challenges in health journalism, Oransky suggested that reporters should produce fewer stories about single studies, and that health and medical journal editors make a concerted effort to publish and disseminate information about studies with null results, which are useful for advancing scientific progress but are often unreported and usually receive less news coverage. He also recommended that scientists review institutional press releases for accuracy and clarity, and that the health science community contact journalists when additional evidence is published that either supports or contradicts findings that have previously been reported in the news.

RESEARCH STRATEGIES

Many workshop participants discussed ongoing research in the fields of health literacy and communication in oncology, as well as avenues for future research, such as communication about cancer genetics, visual design strategies in messaging, and health insurance literacy.

National Cancer Institute’s Research Portfolio and Priorities for Future Research

April Oh, program director of the NCI Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch, said that addressing health literacy and its contributions to health disparities is a major NCI research priority. NCI’s priorities for health literacy research include assessing the effects of tailored and targeted communication, understanding the digital divide and its impact on health disparities, developing strategies for communicating uncertainty and

complex cancer information to diverse populations and those with limited health literacy, and applying mixed method approaches to investigate challenges associated with limited health literacy.

Oh noted that in 2016, NCI decided to integrate health literacy into funding announcements across the institute, rather than maintaining it as a separate program. This change reflects the understanding that health literacy cuts across a wide range of health issues and is fundamental to achieving health equity.

An internal review of NCI’s portfolio of health literacy research found that grant applications with aims related to health literacy primarily focused on the development or evaluation of interventions within particular racial or ethnic populations and addressed cancer screening, informed and shared decision making, or patient–clinician communication. Oh noted that achieving the goal of equity in health communication will require multilevel, multicomponent interventions that emphasize reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance (Glasgow et al., 1999).

The research portfolio review also found that many of the NCI-funded health literacy projects addressed the intersection between health literacy and technology: between 2010 and 2013, the proportion of applications that considered technology increased from 58 percent to 78 percent. Oh noted that although access to mobile phones is now almost ubiquitous, there is still a divide in how people use information from the Internet (Robinson et al., 2015; van Deursen and van Dijk, 2019).

Oh noted that future NCI priorities for health literacy and communication research include

- Reducing communication inequalities, especially at the intersection of health literacy and digital health;

- Developing multilevel and multicomponent interventions;

- Evaluating participatory methods to develop health literacy interventions across patient, clinician, and organizational contexts;

- Examining health literacy in dissemination and implementation research and iterative approaches to understand behavior change; and

- Studying settings and contexts in which the research is occurring, to ensure that interventions are not unintentionally exacerbating health inequalities and disparities.

Oh urged investigators to work across disciplinary boundaries and consider implementation strategies for their interventions. “While you may not think of yourself as a dissemination or implementation scientist, you have a voice in that process,” she said. “We have to think about disseminating these interventions and tools . . . and about how to better design our interventions to be ready for implementation.”

Effective Communication About Cancer Genetics

Galen Joseph, professor in the Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); member of the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center; and affiliate faculty at the Center for Vulnerable Populations at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, noted that genetics play an important role across the cancer continuum. However, there are ongoing challenges for integrating genetics in cancer care. One of these challenges is the under-representation of minority populations in genomic databases, which creates barriers to high-quality care for diverse populations (Smith et al., 2016). For example, genome-wide association studies have largely been conducted on individuals of European descent (Popejoy and Fullerton, 2016). As a result, genetic risk scores are less accurate for people of color in the United States. Underrepresentation of minorities also complicates the interpretation of test results for hereditary cancers. Many genetic variants that are more common in minority populations are missing from genomic databases, making it difficult to determine their associated risk. Joseph noted that expanding the diversity of genomic databases is a critical component of the research program funded by NIH called All of Us,17 as well as other NIH initiatives, including the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research consortium (CSER).18 She noted that the funding announcement for CSER’s second phase includes a requirement that at least 60 percent of the population be composed of underrepresented groups (Amendola et al., 2018).

Another challenge for integrating genetics into cancer care is the low level of genomic literacy in the United States (Hurle et al., 2013), which is further complicated by the complexity and uncertainty of genomic information. She said this is true not only for patients, but also for clinicians, who increasingly need to interpret genetic testing results (Ha et al., 2018). “We know that we need to improve genomic literacy in order to realize the promise of genomic medicine,” said Joseph.

Joseph said that a study assessing the quality of communication in genetic counseling for patients at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancers in safety net clinics found a communication disconnect between genetic counselors and patients (Joseph et al., 2017). While counselors are trained in communication and think of themselves as skilled communicators, patients said they were confused by complex terminology and perceived that counselors provided too much information that was not always relevant for them. Moreover, patients reported that counselors unintentionally inhibited dialogue and

___________________

17 See the All of Us homepage at https://allofus.nih.gov (accessed October 25, 2019).

18 See the CSER homepage at https://cser-consortium.org (accessed October 25, 2019).

engagement by overloading them with information, but reported that there was insufficient information about recommendations for subsequent care.

To address the challenge of achieving effective communication among patients who have limited health literacy, Joseph and her colleagues developed an intervention based on four principles: (1) The clinician, not the patient, is responsible for effective communication; (2) All patients may benefit from plain language, known as the health literacy universal precautions;19 (3) Patient comprehension can—and should—be verified; and (4) Adapting content to meet the health literacy and numeracy needs of individual patients requires commitment, flexibility, and practice.

Working with genetic counselors who participated in the initial study, Joseph’s team developed and conducted a 4.5-hour training program on strategies to apply these four principles. The intervention also included a component on best practices for collaborating with interpreters to improve communication among genetic counselors and individuals who have limited English proficiency. Results from a pilot study demonstrated that genetic counselors successfully implemented these strategies and that patients were able to sufficiently understand the results and implications of their genetic tests (Joseph et al., 2019).

Joseph stressed that graduate education for genetic counselors should embed communication training and relationship building across all curricula. She added that clinicians should strive for clarity and conciseness when communicating complex health information, even if this simplification reduces precision.

Visual Design Strategies to Improve Cancer Communication

Allison Lazard, assistant professor in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and associate member of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, said that cancer communication needs to be engaging and relevant for the intended audience: “We need to know what they think and feel, how they behave, and once we have an understanding of those [things], we can turn to the objective designs.” Lazard added that effectively conveying health information requires consideration and assessment of subjective user experiences through an iterative process of testing and refinement.

Lazard noted that individuals evaluate the quality of health information in the first few milliseconds of exposure, which suggests that messages are

___________________

19 See the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit at https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/index.html (accessed August 16, 2019) for an example of a universal precautions toolkit.

judged on their design rather than on their content (Lazard et al., 2016). She noted that the health communications literature often recommends the use of effective design, but often fails to identify the objective properties, principles, or strategies of effective design. Lazard proposed the following five principles for effective, clear, and patient-centered design:

- Image relevance: select images relevant to the intended audience. This can be accomplished through pilot testing that asks members of the intended audience to view potential images and identify those that resonate most with the proposed messaging (Lazard et al., 2017).

- Information cues: present information so it can be interpreted at a glance. Audiences prefer designs that present qualitative information supported by contextual cues, even if the simplification reduces precision (Byron et al., 2018; Lazard et al., 2019a).

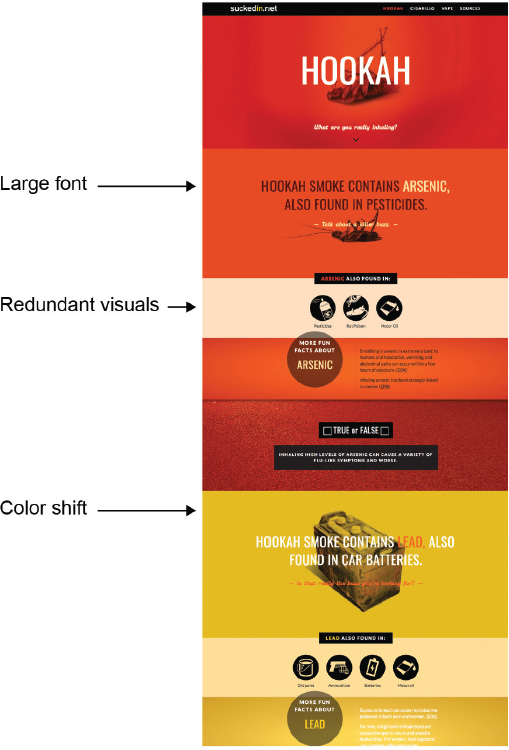

- Visual hierarchy: use design to guide users’ attention. Design elements—such as large font size and redundant visuals—can be used to direct readers to the most salient information, while color shifts can be used to indicate the introduction of new topics (Lazard et al., 2019b) (see Figure 6).

- Social presence: elicit the feelings of a social experience. In the absence of face-to-face communication, design cues such as human imagery and chat functions can facilitate improved user attention, as well as the perceived trustworthiness and usefulness of the message.

- Mental models: understand the audience’s expectations for the message and interface. Designing effective health messages requires understanding and meeting users’ expectations and preferences for communication, even if they differ from those of the public health community.

The Role of Health Insurance Literacy in Reducing Patient Financial Burden

Mary Politi, professor in the Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, noted that selecting among health insurance plans requires advanced numeracy skills and comprehension of complex and unfamiliar concepts. However, lack of adequate insurance is associated with serious health and financial consequences; patients with inadequate coverage are more likely to avoid necessary care and to face large financial burdens associated with care (Smith et al., 2018; Tipirneni et al., 2018). Politi noted that patients with cancer are particularly vulnerable to these outcomes. The high costs of cancer care, including patients’ cost-sharing requirements for their care, are associated with missed medical appointments and rationing of prescriptions, even among

SOURCE: Lazard presentation, July 15, 2019.

patients who have private insurance (Bouberhan et al., 2019; Casilla-Lennon et al., 2018; Dusetzina et al., 2014; Nipp et al., 2016). Politi added that the high financial burden associated with cancer care extends beyond medical consequences; for example, patients with cancer who face high care costs report low quality of life and high levels of medical debt (Banegas et al., 2016; Kale and Carroll, 2016; Ramsey et al., 2013).

Politi said that one opportunity to mitigate financial burdens of care involves clinicians openly discussing treatment costs with patients. She said a survey found that 50 percent of patients reported a desire to discuss costs of

care with their clinicians (Bestvina et al., 2014). These conversations enable patients to make informed decisions about their care and can also help to lower costs with or without making treatment modifications, such as helping a patient enroll in co-pay assistance or switching to a generic medication (Zafar et al., 2015). Politi stressed that clinicians should be proactive in discussing costs of care with patients, rather than avoiding the conversation until financial distress motivates a patient to initiate this discussion. She added that improved clinician training on how to engage patients in these discussions is needed to facilitate and support these important conversations.

Politi described the development and implementation of a web-based, mobile-friendly tool to help patients choose between health insurance plans, called Improving Cancer Patients’ Insurance Choices (I Can PIC). This tool helps patients to (1) understand health insurance and how to use it to manage care, (2) talk to providers about care costs, and (3) identify resources to help offset care costs. The tool also includes a cost calculator that can estimate how much money an individual is likely to spend on their health insurance and care, given their age, gender, type of cancer, type of insurance, and health conditions. In an assessment of I Can PIC, patients who used the tool had more knowledge about health insurance and more confidence in their understanding of insurance terms than patients who did not use the tool. Users were also able to accurately describe complex trade-offs between insurance plans’ costs and coverage.

PROCEDURES, POLICIES, AND PROGRAMS TO ASSESS AND ADDRESS HEALTH LITERACY NEEDS

Many workshop participants described procedures, policies, and programs that health care organizations can employ to assess and address the health literacy needs of patients and their families.

Strategies for Health Care Organizations to Address Low Health Literacy

Urmimala Sarkar, professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at UCSF and associate director of the UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations, described the vision for a health-literate health care organization: it is one where everyone—members of the health care team, the patient, and family members—has the same information, which enables seamless communication and helps patients and clinicians engage in shared decision making.

Sarkar said current communication efforts fall short of this goal and used SCPs as an example of suboptimal communication in health care. She noted

that SCPs are intended to travel with patients after they complete cancer treatment because they contain critical information to guide their subsequent care. Sarkar noted that the effectiveness of SCPs has not been firmly established and their use is hindered by suboptimal implementation (Mendelsohn et al., 2016; Tevaarwerk and Sesto, 2018). Sarkar and her colleagues assessed whether the use of SCPs by health care organizations included the SCP elements recommended in the report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition (IOM, 2006), and whether SCPs met patient usability standards, as measured by the Suitability Assessment of Materials.20 They collected 16 SCP documents from safety net hospitals, community hospitals, academic medical centers, and integrated care delivery systems in California and found that most of the plans did not include the recommended elements, and that their language was too complex for patient comprehension. Furthermore, only one SCP document exceeded the “adequate” rating for cultural appropriateness. She noted that SCPs are traditionally created to communicate care information to both patients and their primary care clinicians, but the information needs of these groups may be too disparate to be met with a single document. Sarkar concluded that as currently developed, SCPs are not an optimal strategy for communicating post-treatment information for survivorship care.

Sarkar suggested that health care organizations fundamentally redesign their SCPs, noting that the utility of the documents will evolve as interoperability of electronic health records (EHRs) is achieved. Sarkar described EHR interoperability as a “policy imperative” and stressed the importance of clinicians being able to directly view records from other health care organizations. She stressed that communication among primary care clinicians and oncologists should not be the responsibility of patients. “That is not to say that patients do not absolutely need to have a treatment summary, but the level of detail that is necessary for patients to have in their hands is not the same as what I need as the primary care physician,” said Sarkar. Sarkar said that to provide better survivorship care, primary care clinicians need to have access to their patients’ oncology records.

Patient Navigation Programs

Pratt-Chapman noted that 80 million Americans have trouble understanding and using health information, which can contribute to a lack of

___________________

20 The Suitability Assessment of Materials rates written materials across six domains: content, literacy demand, graphics, layout and type, learning stimulation and motivation, and cultural appropriateness. See SAM: Suitability Assessment of Materials for Evaluation of Health-Related Information for Adults at http://aspiruslibrary.org/literacy/SAM.pdf (accessed September 26, 2019) for additional information.

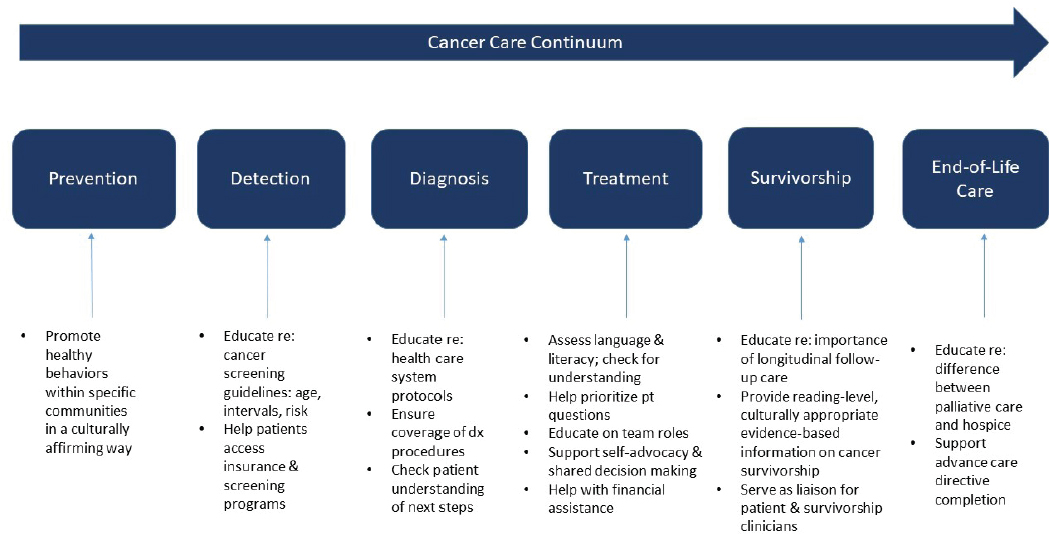

preventive care, reduced adherence to treatment regimens, increased hospitalization, lower health status, and higher mortality (Berkman et al., 2011). Pratt-Chapman stressed that patient navigation programs can be a key strategy for reducing the adverse effects of health literacy limitations, noting that navigators can help coordinate patients’ care, assess and address barriers to care, and promote healthy behaviors and effective coping strategies (NASEM, 2018a). She added that navigation services can help support patients’ health literacy and communication needs across the continuum of cancer care (Pratt-Chapman et al., 2015) (see Figure 7).

Pratt-Chapman said that patient navigation services should be targeted to address particular patient needs within an organization or community (Willis et al., 2013) and that navigation services need to be sensitive to the contextual barriers to effective care delivery. She proposed that navigation services and providers be tailored to meet specific health objectives: for example, she said that community health workers would be most appropriate to deliver health promotion interventions, while nurse navigators would be most appropriate to provide symptom management during active cancer care.

Pratt-Chapman said that it is often difficult to secure and sustain funding for patient navigation services, and she proposed several opportunities to make the business case for patient navigation and improving sustainability:

- Document the value of patient navigation, both for improving patient care and for reducing health care expenditures (Kline et al., 2019). She noted that metrics such as patient satisfaction, patient engagement, time to diagnosis and treatment, patient adherence, reduced acute encounters, greater efficiency, and cost savings can be used to demonstrate the value of navigation programs. Pratt-Chapman also noted that navigation can serve as a cost-saving measure under both value-based and fee-for-service reimbursement models. For example, patient navigators at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, a value-based system, saved $781.29 per navigated patient through reduced emergency department, intensive care unit, and unplanned hospital admissions (Kline et al., 2019). At the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which operates on a fee-for-service basis, patients with navigation support were 10 percent more likely to stay in the health system and receive multiple treatment modalities (Kline et al., 2019).

- Provide health systems with up-front investments and ongoing financial support for team-based cancer care. Pratt-Chapman noted that the Oncology Care Model,21 a demonstration project of the Centers

___________________

21 Additional information is available at https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care (accessed August 16, 2019).

NOTES: While education on palliative care, hospice care, and advanced care planning are included in this diagram as a component of end-of-life care, they are important across the continuum of cancer care (IOM, 2013b). dx = diagnosis; pt = patient.

SOURCES: Pratt-Chapman presentation, July 16, 2019; Pratt-Chapman et al., 2015. Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. Pratt-Chapman, M, Willis A, and Masselink L. Core competencies for oncology patient navigators. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2015;6:16–21. © Green Hill Healthcare.

- for Medicare & Medicaid Services, provides oncology practices with $160 per patient per month and requires the use of patient navigation. Although Pratt-Chapman questioned whether $160 per patient per month is sufficient, she supported the use of payment incentives for care coordination as a potentially viable model to support patient navigation. She added that the 2018 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Policy Summit working group also recommended coding mechanisms to reimburse team-based care and that several proposed congressional bills would facilitate team-based reimbursement under Medicare and Medicaid.

- Promote the use of flexible budgeting to correct misaligned incentives and enable all participants to share in the financial benefits of improving the quality and reducing the costs of care. She noted that with navigation services, there is often misalignment between those that fund and provide navigation services and those that financially benefit, and that navigation programs may increase a health care organization’s costs in the short term. Pratt-Chapman suggested that flexible budgeting could be used to reduce these barriers (Nichols and Taylor, 2018). Pratt-Chapman said the key is to use a trusted broker to share cost savings among all participants involved.

Supporting Patient Self-Management in Oncology