3

DOE SBIR/STTR Processes

This chapter describes the DOE processes for selecting SBIR/STTR topics, reviewers, and award winners within the 12 program offices that participate in the SBIR/STTR program,1 as described by each office’s topic and portfolio managers. It also considers the impact of DOE processes on the participation of woman-owned firms and firms owned by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals. The principal sources of data for this chapter were discussions, carried out by members of the committee, with topic and portfolio managers (and sometimes other staff involved in the SBIR/STTR programs) from each of DOE’s 12 program offices. Each discussion covered a similar set of topics and was approximately 45 to 90 minutes long. (See chapter annex for the list of topics and participants). The committee’s analysis was also informed by discussions with small business owners, SBIR/STTR applicants, and awardees from underrepresented groups. Additional data and background information were obtained from the DOE website and the committee’s data request to the SBIR/STTR Programs Office.

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

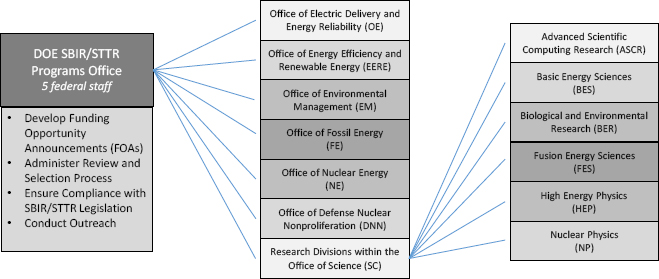

The chapter begins with a description of the administrative structure of the SBIR and STTR programs within DOE. Within the agency, there are 12 different program offices, each with its own staff assigned to SBIR and STTR. A central DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office administers the funding announcements, oversees and administers portions of the review process, and

___________________

1 There are currently 13 program offices that participate in SBIR/STTR programs. After the committee completed its interviews, the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability was divided into the Office of Electricity and the Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security and Emergency Response. See https://www.energy.gov/science/sbir/small-business-innovation-research-and-small-business-technology-transfer.

finalizes the selection of awardees based on the individual offices’ rankings. Each of the 12 program offices is responsible for the selection of funding opportunities and reviewers and the ranking of potential awardees from the office’s topics, from which the final awardees are determined by the SBIR/STTR Programs Office based upon the amount of award funding that is available for each program in each office. Overall, the committee found considerable consistency across the offices in terms of their adherence to the formal processes and procedures articulated by the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office.

Individual program offices view the SBIR/STTR programs from the lens of their unique scientific missions, and the committee found differences across offices in how they identify and use small businesses to meet their research and development needs. These scientific priorities also influence how they view commercialization. For example, some program offices focus on obtaining specialized components for advancing science and see that as a commercialization outcome. In these instances, there may be few firms with the appropriate expertise, hence a greater reliance on small firms that win multiple SBIR/STTR awards from those offices.

DOE, like other administrating agencies, has tailored its implementation of the SBIR/STTR programs to support the specific missions and goals of its programmatic offices and research programs that fund awards. (See Table 3-1.) In some instances, there is tension between the selection of topics and awardees that advance the program office’s mission and those that lend themselves to broader commercial outcomes. Similarly, tension may exist between selecting topics and awardees that can advance energy innovation and those that are ready to be licensed or sold to the other government agencies or the private sector. As described later in this chapter, the topic selections are determined, in part, by the budgeted amounts for each energy subsector appropriated by Congress along with discussions between DOE program managers and their relevant stakeholders. The committee found that tensions between innovation and commercialization were largely dependent upon the size and composition of the stakeholder base. Within program offices that were larger and had more varied stakeholders (such as the Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research), a larger number of awardees exist that could address both mission and program needs and may also have commercial appeal. This is again, as described more below, a result of the heavy reliance on their identified researcher and industry community to drive topic selection, reviews, proposals, and awards.

One area of consistency between program offices that does not benefit the program is that all program offices focused solely on the technical merit and technical capabilities of the reviewers and awardees, rather than seeking out geographic, racial, gender, or organizational diversity. Most offices believe their community is a finite, relatively small group of scientists with specific technical expertise. Broadening how each office depicts its respective communities would widen the diversity of viewpoints and perspectives and increase novelty, innovation, and creativity.

TABLE 3-1 Funding Allocations, Source of Topics, and Source of Reviewers for DOE Program Offices Involved in SBIR/STTR (FY 2018)

| Name of Office | Mission | FY 2018 SBIR/STTR Funding Allocations | Number of Budget Control Lines | Source of Topics | Source of Reviewers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) | To discover, develop, and deploy computational and networking capabilities to analyze, model, simulate, and predict complex phenomena important to the Department of Energy | SBIR: $19,040,00 STTR: $2,678,000 |

1 | Research community which includes DOE labs/academia/industry | Industry, academia, potential consumers, national labs |

| Basic Energy Sciences (BES) | To support fundamental research to understand, predict, and ultimately control matter and energy at the electronic, atomic, and molecular levels in order to provide the foundations for new energy technologies and to support DOE missions in energy, environment, and national security | SBIR: $53,652,000 STTR: $7,545,000 |

1 | National labs; scientific user facilities (e.g., synchrotron light source facilities) | National labs, academia, and industry. A pool of reviewers who are “well respected and with whom we have a very close relationship” |

| Biological and Environmental Research (BER) | To support transformative science and scientific user facilities to achieve a predictive understanding of complex biological, earth, and environmental systems for energy and infrastructure security, independence, and prosperity | SBIR: $21,393,000 STTR: $3,007,000 |

1 | Workshops with scientific community stakeholders and the office’s advisory board | National labs and research community |

| Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) | To expand the fundamental understanding of matter at very high temperatures and densities and to build the scientific foundation needed to develop a fusion energy source | SBIR: $11,598,000 STTR: $1,631,000 |

1 | National labs (especially the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab) | National labs and other experts in plasma physics |

| Name of Office | Mission | FY 2018 SBIR/STTR Funding Allocations | Number of Budget Control Lines | Source of Topics | Source of Reviewers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Energy Physics (HEP) | To understand how our universe works at its most fundamental level | SBIR: $21,365,000 STTR: $3,004,000 |

1 | Industry leaders, national labs (Fermi, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Brookhaven, Lawrence Berkeley) | Industry leaders, national labs (Fermi, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Brookhaven, Lawrence Berkeley) |

| Nuclear Physics (NP) | To discover, explore, and understand all forms of nuclear matter | SBIR: $16,875,000 STTR: $2,373,000 |

1 | National labs (Argonne, Brookhaven, Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator, Los Alamos, and Oak Ridge (to a lesser extent)) and universities | Academia and national labs |

| Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation (DNN) | To prevent nuclear weapons proliferation and reducing the threat of nuclear and radiological terrorism around the world | SBIR: $8,545,804 STTR: $1,201,753 |

1 | National labs | National labs, academia, other federal labs, internal advisors |

| Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) | To create and sustain American leadership in the transition to a global clean energy economy | SBIR:$50,991,599 STTR:$7,170,348 |

9 | Office’s roadmap, created using input primarily from national labs and academia, with some input from industry, trade associations, and consultants | Reviewer selection contracted to the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education |

| Environmental Management (EM) | To address the nation’s Cold War environmental legacy resulting from five decades of nuclear weapons production and government-sponsored nuclear energy research | SBIR: $1,120,000 STTR: $157,500 |

1 | National labs and other federal, interstate, and state government agencies via their roadmaps | National labs (Pacific Northwest, Savannah River, Oak Ridge, Lawrence Livermore) |

| Fossil Energy (FE) | To ensure the nation can continue to rely on traditional resources for clean, secure and affordable energy while enhancing environmental protection | SBIR: $14,875,460 STTR: $2,091,862 |

8 | National Energy Technology Laboratory, academia, and companies | National Energy Technology Laboratory, other national labs, academia, and industry |

| Nuclear Energy (NE) | To advance nuclear power to meet the nation’s energy, environmental, and national security needs | SBIR: $20,600,000 STTR: $2,873,502 |

4 | National labs and 15-20 universities with nuclear engineering departments (usually from Brookhaven, other labs, and universities with nuclear reactors) | Review process managed by Idaho National Laboratory |

| Office of Electricity (OE) | To ensure the nation’s most critical energy infrastructure is secure and able to recover rapidly from disruptions | SBIR: $5,040,864 STTR: $708,872 |

5 | National labs, utilities, and key vendors | Large vendors, academia, national labs, utilities |

SOURCE: Department of Energy.

OVERVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE AT DOE SBIR/STTR

DOE has established processes that aim to support its overall mission and the missions of its programmatic offices and research programs that sponsor SBIR/STTR activities. DOE has centralized some functions and activities into a department-wide SBIR/STTR Programs Office housed within the Office of Science while assigning other functions to the programmatic offices and research programs. DOE’s program offices, as they relate to the agency’s SBIR/STTR initiatives, are divided into 12 individual offices as depicted in Figure 3-1.2 The 12 offices that participate in the SBIR/STTR programs include six research programs housed in the Office of Science and an additional six program offices outside the Office of Science. Each participating office or division has authority or obligation to develop topics for solicitations, suggest individuals who could serve as application reviewers, and rank applications for final award, with the final cut off applied by the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office based on the level of available funding. The negotiation of all grants, issuance of new and continuation awards, and final closeout of grants is handled by the DOE Chicago Office.

Table 3-1 shows the SBIR and STTR allocations for fiscal year (FY) 2018 for each of the DOE program offices involved in the agency’s SBIR/STTR programs. The largest office is Basic Energy Sciences and, as such, is often a point of collaboration on SBIR/STTR topics of mutual interest with other offices. Also shown in the table is the number of budget control lines governing the appropriation received by each office. Section 301 (d-g) of DOE’s appropriations law directs DOE to adhere to congressional budget control points, and in FY 2018, DOE’s Office of General Counsel determined that Section 301 also applies to the funds allocated to SBIR/STTR. As shown in the table, all of the Office of Science programs have a single budget control line, which provides flexibility in how the office can fund projects across research topics, whereas many of the applied offices with multiple control lines have less flexibility. The application of Section 301 to SBIR/STTR funding constrains what offices can fund with the SBIR/STTR programs to meet broad agency research and development needs.

The central SBIR/STTR Programs Office coordinates and works with staff within each of the 12 offices, who often take on roles related to SBIR/STTR as just part of their overall job responsibilities. Principal among these roles is that of technical topic manager (TTM). The TTMs handle the tasks of gathering input from the research community and getting topics and subtopics written for funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) before deadlines set by the SBIR/STTR Programs Office. TTMs manage the selection of reviewers and oversee the technical merit review process, though parts of this are sometimes subcontracted

___________________

2 Starting in FY 2019, the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability split into two offices—one on grid reliability (Office of Electricity Delivery) and another on cybersecurity (Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response).

NOTE: There are currently 13 program offices that participate in SBIR/STTR programs. After the committee completed its interviews, the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability was divided into the Office of Electricity and the Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response.

to a DOE national lab or other organizations. For simplicity, the descriptions below assume that all of the review-related responsibilities of the TTMs are conducted in-house, unless otherwise noted.

Offices take a variety of approaches to staffing the position of TTM. Although Congress mandates that funds be allocated to the SBIR/STTR programs, it does not separately fund the administration of the programs, and unlike the central SBIR/STTR Programs Office, staff in the 12 program offices spend the bulk of their efforts on non-SBIR/STTR programs—with the result that the role of TTM is generally part-time and there can be one or more TTMs within an office.

Another staff role connected to administering SBIR/STTR within program offices are those of portfolio manager. The portfolio manager works with the TTM(s) to coordinate SBIR/STTR-related activities within a program office, particularly in the final ranking of submitted applications, in consultation with senior management.

Administration of SBIR/STTR at ARPA-E

Although it is part of DOE, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy’s (ARPA-E’s) SBIR/STTR programs were not included in this

assessment.3 ARPA-E’s SBIR/STTR programs are not administered through DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office. Instead, ARPA-E develops SBIR/STTR programs through the same process as its non-SBIR/STTR programs and runs them concurrently. According to ARPA-E’s responses to the committee’s questions, over the past eight years its small business funding via SBIR/STTR programs has averaged 3.4 percent of its extramural research and development budget, although nearly one-third of its overall funding goes to small businesses. Unlike DOE’s SBIR/STTR programs, ARPA-E uses combined awards (Phase I/Phase II) to reduce gaps between phases, requiring awardees to certify eligibility to move to the next phase. ARPA-E differs from DOE in that it primarily uses cooperative agreements (not grants) for its awards and its authorizing legislation specifies that its director is responsible for “terminating programs carried out under this section that are not achieving the goals of the programs” (ARPA-E, 2010).

THE DOE SBIR/STTR TOPIC DEVELOPMENT AND APPLICATION PROCESS

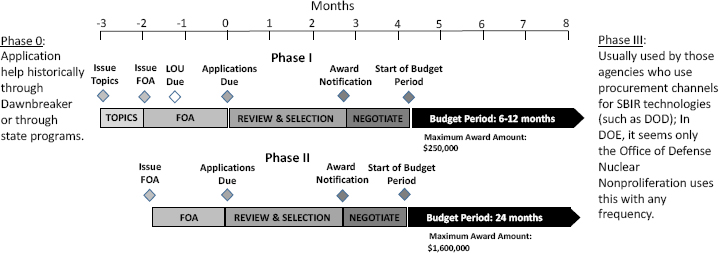

The formal SBIR/STTR process for each participating DOE program office begins each year with a period of topic development followed by an announcement of topics for Phase I. This, in turn, is followed (usually about a month later) by a corresponding FOA. Each year there are two sets of topic announcements and corresponding FOAs for Phase I, with some program offices participating in the first set (Release 1) and the remainder participating in the second set (Release 2).4 Applications are due about two months after FOAs are released, and letters of intent are required one month prior to the application due date. Letters of intent allow TTMs to preview expected applications in order to anticipate the numbers and types of reviewers that will be needed. Each proposal is reviewed by three technical merit reviewers, who are generally recruited by the TTM. Once these reviews are received, TTMs check the reviews to assess that feedback was appropriate, and proposals are rank-ordered based on these reviews and office priorities.

The process for Phase II applications and review are similar, with some exceptions. Like the process for Phase I, there are two Phase II FOAs each year; however, the topics for Phase II applications are those for the previous years’ Phase I processes. This reflects the fact that initial Phase II awards for a given year are follow-ons to Phase I awards from the previous year, and Phase IIA, IIB, and IIC awards are made to projects that received Phase I awards earlier than the

___________________

3 The National Academies recently completed an assessment of ARPA-E (NASEM, 2017).

4 Historically, Release 1 was predominantly from programs within the Office of Sciences (plus the Office of Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation), and Release 2 included the other program offices. More recently Release 1 has included only four programs within the Office of Science (Advanced Scientific Computing Research, Basic Energy Sciences, Biological and Environmental Research, and Nuclear Physics), and Release 2 has included the remaining programs within the Office of Science as well as the other programs.

previous year. As with the Phase I process, Phase II applications are due about two months after each FOA is released, and letters of intent are required for Phase IIA, IIB, and IIC applicants but not for initial Phase II applicants. Each Phase II application is reviewed by three technical merit reviewers, like Phase I, and is also subject to a separate commercialization potential review. Program offices have primary responsibility for managing the technical merit review of Phase II proposals, as they do for Phase I proposals and ranking the applications, but the Phase II commercialization potential review is primarily handled by the SBIR/STTR Programs Office.

The process of topic and sub-topic formation for Phase I FOAs is consistent across program offices. In every case, TTMs gather input from the scientific community on their funding priorities. Stakeholders are usually research scientists in academia, industry, and the affiliated national research laboratories. In one case, this also included state government agencies. In some offices, such as Fossil Energy, TTMs have a standard form that they send to stakeholders to elicit topic recommendations. Thus, topics hew closely to the scientific mission of the office and the needs of their scientific community. At the same time, as discussed later in this chapter, a narrow view of the scientific community may create barriers to improving participation among underrepresented groups. Topics and subtopics cover a broad range of research and development areas, and “other” subtopics are often included to allow for innovative proposals that may not fit under the defined set of subtopics.

For both Phase I and Phase II awards, the review and award selection process must be completed within 90 days of the application deadline. (See Figure 3-2 for a timeline of the entire process for Phase I and Phase II.) The tight timeframe makes the process challenging.

Program offices adhere consistently to the administrative process established by the DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office. In fact, many of the program managers noted the process has become far more consistent, transferable, and straightforward from year to year since the current director of the SBIR/STTR Programs Office took over. Apart from these significant, high-level areas of standardization, there are a number of key differences across offices, as described in this chapter. These differences are a reflection of the flexibility of the SBIR/STTR programs as implemented by DOE.

“Phase 0” Assistance for First-time Phase I Applicants

DOE offers a Phase 0 program to provide proposal assistance to first-time Phase I applicants. The program provides training, mentoring, and assistance with communication and market research, technology advice and consultation, and budget preparation, as well as specific assistance in preparing and submitting

NOTE: FOA = Funding Opportunity Announcement; LOI = Letter of Intent.

SOURCE: Adapted from Department of Energy.

a letter of intent and Phase I proposal. DOE funds Phase 0 and executes it through a contractor.5 The program was originally aimed toward underrepresented groups such as woman-owned small businesses, minority-owned small businesses, and firms from states with historically low SBIR/STTR applications to the DOE programs, but it has been available to all first-time applicants since the most recent SBIR/STTR reauthorization. There is evidence that the Phase 0 program has been effective. As shown in Table 3-2, 25 percent of applicants receiving Phase 0 assistance for the period FY 2015 to FY 2018 won Phase I awards, similar to the overall success rate of Phase I applications.

TABLE 3-2 DOE SBIR/STTR Awards to Firms Receiving Phase 0 Assistance (FY 2015-2018)

| Funding Opportunity Announcement | Applicants Who Received Phase 0 Assistance | All Applicants Success Rate (percent) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Applicants | Number of Awardees | Success Rate (percent) | ||

| Phase I | 315 | 79 | 25 | 25 |

| Phase II | 53 | 14 | 26 | 50 |

SOURCE: Department of Energy SBIR/STTR Programs Office data request.

___________________

5 The DOE SBIR/STTR Phase 0 Assistance Program is administered by Dawnbreaker. See http://www.dawnbreaker.com/doephase0.

Limiting the Inflow of Proposals

Many program offices noted that while they want to get as many high-quality proposals as possible, they have limited capacity to process them, especially with regard to getting enough reviewers. This is a common problem in organizations that seek novel ideas but have a limited capacity to process them (Piezunka and Dahlander, 2015). More specific to this context, many program offices perceive reviewers in appropriate technical areas to be scarce, making this the key constraint on the number of proposals they can assess. Many offices use a variety of methods to manage the inflow of proposals, which they believe improves the efficiency of the overall award process and results in higher-quality, more-targeted proposals. Two aspects of the award process drive these efforts. First, the timeline is defined by statute: applications must be processed within 90 days of the application deadline. Second, three technical merit reviews are needed for each proposal, and TTMs sometimes ask more than three reviewers to examine a proposal in order to ensure that three reviews are received.

The inflow of proposals is also managed in other ways. Requiring letters of intent for all Phase I proposals makes it possible to notify prospective applicants whether their intended application is within the scope of the FOA. This discourages applicants from submitting non-responsive proposals. Second, starting in FY 2012, the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office set a limit of 10 applications by a single applicant to each Phase I solicitation. Third, some TTMs, whose technical needs remain similar year after year, keep the same topics and fine-tune subtopics in order to reduce the number of proposals they receive. Finally, at least one office interviewed eliminated the use of an open-ended “other” category from its list of topics. The managers felt that the time and resources spent reviewing these proposals far outweighed any benefit from an unexpected, unsolicited gem. Even for some of those offices that do find use in adding such an open-ended category, they use language to strongly suggest that only applications that clearly fit the office’s scientific needs will be considered.

Not all offices, however, sought to reduce the flow of proposals. At least one office reported that the “other” category had yielded surprising and innovative research. Another office expressed the need to expand the number of applicants beyond its existing community. This coincided with new or expanded scientific goals within the office’s mission, which led to different SBIR/STTR topics and, therefore, a different population of firms. For example, this office had a new need for research on dust suppression technologies, which led to applications from firms in forestry that had not submitted applications previously.

The Review Process

Once applications are submitted, the clock starts ticking on the 90-day deadline for the review and award processes. DOE evaluates Phase I SBIR/STTR proposals using a three-step process: (1) initial screening, (2) technical merit review, and (3) final selection of awards. The initial screening is done by TTMs

in the individual offices and the SBIR/STTR Programs Office, who evaluate the applications to ensure they meet the stated FOA requirements, are responsive to a topic and subtopic, contain sufficient information for a meaningful technical merit review, are for research or for research and development, do not duplicate other previous or current DOE-funded work, and are consistent with program area’s mission, policies, and other strategic and budgetary priorities. If the application passes the initial review, it is sent to external reviewers for technical merit review, which is based on the following equally weighted criteria:

- Strength of the scientific/technical approach (degree of innovativeness, evidence of a significant scientific/technical challenge, and thoroughness of the proposal)

- Ability to carry out the project (qualifications of team members, merits of the work plan, consistency of project size with budget requested)

- Impact of the proposed project (technical/economic benefits, potential for marketable product, ability to attract post-SBIR/STTR funding) (DOE, n.d.c)

Phase II applications are evaluated according to the same process and technical merit review criteria, with the applicant’s ability to carry out the project also judged by the degree to which the applicant’s Phase I has proven the feasibility of the concepts. These criteria remain equally weighted for initial Phase II and Phase IIA applications, but for Phase IIB and Phase IIC applications, impact has twice the weight of the other criteria. Phase II applications are also subjected to an additional commercialization potential review. The DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office has the primary responsibility for reviews of the commercialization potential, which are conducted by subcontractors to CTR Management Group, LLC. Applications that receive a poor commercialization potential review may be deemed ineligible for funding.

Experts from national labs, universities, government, and the private sector serve as reviewers for the technical merit review. The TTMs maintain a list of reviewers in most offices and update the list by keeping in touch with experts at national labs, attending technical conferences, and reading the literature. In one program office, reviewers must be “certified by their management panel to be in the database.”

Reviewers for DOE SBIR/STTR applications are distributed across the country, and almost half are from national labs, one-third are from universities, and the remaining 20 percent are about evenly split between government and industry (see Tables 3-3 and 3-4). This distribution by source of reviewers varies by program office with some relying primarily on reviewers from national labs and others using a mix of reviewers from across sectors. Depending on the focus of the research, some program offices use reviewers from across the national labs, while others focus on one or a few labs.

TABLE 3-3 Sources of DOE SBIR/STTR Phase I and II Reviewers, by Region (FY 2017)

| Region | U.S. State or Country | Percentage of All Reviewers |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Northeast | CT, DC, DE, MA, MD, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, PR, RI, VT | 24 |

| U.S. Southeast | AL, AR, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, VA, WV | 20 |

| U.S. Mid-West | IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, OK, SD, WI | 20 |

| U.S. Northwest | AK, ID, MT, OR, WA, WY | 7 |

| U.S. West | AZ, CA, CO, HI, NM, NV, TX, UT | 27 |

| Non-U.S. Countries | Canada, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Sweden, Swizterland, Japan, The Netherlands, Taiwan, United Kingdom | 2 |

SOURCE: Department of Energy SBIR/STTR Programs Office.

TABLE 3-4 Sources of DOE SBIR/STTR Phase I and II Reviewers, by Sector (FY 2018)

| Organization Affiliation | Percentage of All Reviewers |

|---|---|

| Business and Industry | 12 |

| DOE National Laboratory | 46 |

| Government | 10 |

| University | 32 |

SOURCE: Department of Energy SBIR/STTR Programs Office.

Program offices vary in how they manage their lists of reviewers. Office of Science programs are familiar with the Portfolio Analysis and Management System (PAMS) used to manage the SBIR/STTR processes—which they use for all their other grant processes—and utilize it for maintaining lists for SBIR/STTR. Other program offices are not as familiar with it and have other systems for maintaining reviewer lists for non-SBIR/STTR grants.

In order to facilitate recruitment of reviewers, program offices offered a variety of different strategies. A few offices contract out or pay for reviewers. One program office pays their reviewers, and its review selection process is managed by Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE), a U.S. DOE Institute whose mission is to enable scientific research through a variety of activities such as providing scientific expertise (ORISE, n.d). Another pays contractors to

conduct reviews but does not pay reviewers from national labs and universities. Yet another uses Idaho National Laboratory to maintain a database of reviewers and to assign reviews. Reviews are conducted in person by some offices and remotely by others. Some offices conduct panel reviews, whereby the program office invites reviewers to spend one or two days to review the proposals individually and then discuss them as a group, in a process similar to review panels run in other agencies such as the National Science Foundation. In other offices, proposals are sent to individual reviewers who conduct the reviews remotely. Occasionally, a teleconference with reviewers is held to discuss and review a proposal.6 Some program offices only request that reviews be conducted remotely and do not have panel reviews, while other offices do a mix of panel reviews and individual reviews.

Each TTM reads all reviewer comments carefully for relevance. If comments are deemed not relevant or unprofessional, the TTM will redact them. All applicants receive anonymized copies of the reviews.

There are notable challenges in administering the review process. Given the 90-day deadline for the review and award processes, delays at any step increase the difficulty of completing the process on time. One source of delay is reviewers who do not respond or who do not submit their reviews within the requested time frame (generally about three weeks); one office said that more than one-third of reviewers do not reply to the initial request. “Review fatigue” can also be a challenge. TTMs take reviewer workload into account, but sometimes this is overtaken by the need to get reviews done within the time frame available. Program offices with smaller research and technical communities have difficulty finding reviewers with the technical expertise to assess the proposals while also not having a conflict of interest. This often means that a small set of reviewers are burdened with a larger proposal set to review, and offices with smaller communities expressed concern about the strain this puts on reviewers.

It should be added that an office’s participation in only one or in both FOA releases within a single fiscal year affects the review process. Most program offices are included in only one FOA release (Release 1 or Release 2). However, some offices do participate in both releases if they choose to engage in cross-release opportunities with an office in a different release. Being in only one release concentrates the work but increases the intensity of finding reviewers. Being in both spreads out the workload but requires care in not asking the same reviewers for reviews more than once a year.

FINAL AWARD PROCESS

According to data provided to the committee by DOE, during FY 2018 the DOE SBIR/STTR programs received 2,665 letters of intent followed by 1,548 Phase 1 proposals, and awarded 395 SBIR/STTR grants—about one grant for

___________________

6 For example, the Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research does this for collaborative proposals (see Box 3-1).

every four proposals (an award rate of 26 percent). An additional 193 proposals were recommended for funding but were not awarded because funds were not available. The grant rate for Phase I awards has been steadily increasing since 2012 with grant rates of 14 percent in FY 2012 and FY 2013, 15 percent in 2014, 17 percent in FY 2015, 21 percent in FY 2016, and 22 percent in FY 2017. The program received 296 Phase II applications and awarded 146 grants, an award rate of 49 percent. The award rate for Phase II awards varied depending on the type of Phase II: for Phase IIA, the award rate was 63 percent (from 27 applications); for Phase IIB, 38 percent (from 52 applications).

Within each program office, TTMs orchestrate award selection. Each TTM starts the award selection process with an examination of the reviewers’ scores and comments. The proposals are binned by their scores into ratings of 1 to 3, with 3 being the highest. Then, within each program office, the portfolio and technical topic managers as a group rank the projects. Occasionally, they may recommend funding a proposal with a score of 2, but they must provide additional justification if the proposal is ranked higher than others with a score of 3. While each program office may have some sense of how many SBIR/STTR grants they will be funding from each FOA, delays in appropriations may obscure the amount available at the time of selection.

If any proposals’ scores are tied, some program offices will give a higher ranking to the one that is newer to the program; others will give a higher ranking to the one that has greater potential to move their program forward.

While the overall process is the same across program offices, the decision making varies depending on their missions and communities. As described in the section that follows, some program offices favor proposals where the commercialization potential is within their scientific program while others allow a broader view of market opportunities. Commercialization time frames also vary. Offices looking for proposals that directly address their program needs may be looking for shorter-run commercialization potential, while those that are more interested in broader commercialization appear to allow proposals with longer time horizons to enter the market. A few examples highlight these different approaches:

- One technical topic manager said “If someone says we’re developing the technology for medical imaging, we’ll reject it because it has to meet our needs.” Another program office said that successful applicants must demonstrate short-term market applications which may be outside of their program’s direct goals.

- Yet another technical topic manager said “What we want to see is a commercial product. What I tell everybody who calls me and contacts us is you need to define who your customer is because it is not me. Don’t tell me ‘here is something that would solve your problem.’ I do not have a problem…. Some of the technologies can take a decade or longer to commercialize.”

- Some technical topic managers are in between. They want to fund technologies that meet their program office goals but also have application to multiple sectors. One program office said they will fund projects that have small commercialization potential if the output will solve an important bottleneck for their research community. However, this same office said that they look for tools that will help their communities but that in the process of advancing scientific needs of the mission, the resulting technologies can also be commercialized elsewhere. Another office noted that they look for some short-term commercial successes in SBIR to complement the higher-risk longer-term non-SBIR projects.

Award Selection

Final award selection takes place once the proposals are ranked, discussed, and selections proposed. The TTM—or in larger offices with multiple TTMs, the portfolio manager—in each program office puts together a package and briefs senior management, usually the office director. Senior management reviews the ranking and anticipated awards. If they have questions, they reach out to the TTMs to ask questions and to see project abstracts. Once approved, the program offices ensure that the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office has the information needed to negotiate the awards. From the rankings, final awardees are determined by the SBIR/STTR Programs Office based upon the amount of funding available for each program in each office.

The SBIR/STTR Programs Office notifies all applicants of selection or non-selection via email approximately 90 days after the application due date, and selections are posted on the DOE SBIR/STTR website within one day after email notifications are sent. Applicants can access reviews for their application whether or not they receive an award, but cannot appeal the award decision.

Program offices’ approaches to ranking applications for award show an emphasis on supporting individual offices’ missions rather than SBIR/STTR program goals such as commercialization or increasing participant diversity. Each office contacted by the committee reported that its processes are tailored first to the office’s or program’s mission, along with other factors such as internal expertise and capacity. Offices with fewer congressional budget control lines indicated that this is simpler and more easily put into practice.

Conversations with program offices also suggest that they emphasize their technical program missions ahead of SBIR/STTR program goals. For instance, when reviewing applications, essentially all offices stated in some way or another that they instruct reviewers first to assess the technical merit. A minority of offices stated that commercialization is also very important while at least one noted that its mission is so early in the cycle of technology development that commercial potential often is difficult to see in proposals meant to help fulfill that office’s program mission. At least one noted that it tries to select projects that look ready to commercialize in less than a year. Too great an emphasis on near--

term commercialization almost by definition precludes supporting long-term innovation. Effectively, then, the offices find themselves forced to choose between selecting projects that support one of the SBIR/STTR program goals but do not support one or more of the others.

Varying approaches to commercialization by program offices affect the topics they issue and the proposals they choose to fund. Variation begins with how managers view the role of the SBIR/STTR program within the wider mission of the office. A number of offices viewed the scope of the SBIR program narrowly. For example, some offices used the SBIR program to fund research on specialized equipment and software with the sole market or use to be in a national lab or by other stakeholders closely tied to the sponsoring office (e.g., university scientists advancing the scientific priorities of the sponsoring office). In these cases, the commercialization goal was the hardening of lab-developed technology, so that reliable applicants, who had successfully delivered solid research in the past, were often of greater value.

Other offices construed “commercialization” more broadly. Some asked applicants to demonstrate a dual-use for the technology (e.g., both a specific program office use and a wider market use). However, at least one office rejected proposals if the commercial market was seen as too distant. For example, a medical use cited by an applicant resulted in rejection because it was viewed as too unrelated to the office’s needs. For others, some signal of commercial value, such as a letter of interest from a large firm, was looked upon favorably.

This variation is driven in part by an office’s mission. An office with specific research needs was more likely to construe a distant commercial market (e.g., not clearly related to the science conducted by the office), such as a medical application, as shifting an awardee’s research away from DOE’s mission. By contrast, other program offices viewed a commercial market as core to their mission. For example, the Office of Electricity’s mission is to harden the nation’s electricity grid. A robust commercial industry is essential to ensuring that grid operators all over the country have access to the necessary technologies. As such, the scale of the intended commercialization also varies. Some sought a high-growth market opportunity, equivalent to what a venture capitalist would seek in a candidate venture for funding. Others sought commercial involvement in a public good or basic science (e.g., particle physics laboratory equipment) where a more limited commercial scope was deemed acceptable.

Budgetary Considerations

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges for some of the program offices is the 301 requirement, which requires each office to allocate its awards in proportion to its budget control lines (DOE M 135.1-1A). If they deviate by more than 10 percent or $5 million from a budget line item, they must go back to Congress and ask to be reprogrammed for each line item that deviates from the original budget allocations. In fact, when program managers were asked how much Congress influences their SBIR funding mandates, 301 requirements and

how they affected their funding allocations was the clear differentiator in responses. Offices that felt more Congressional oversight were those that had more burdens due to these administrative reforms.

301 requirements particularly affect offices with multiple control lines, mostly those outside of the Office of Science (see Table 3-1), while other program offices generally had both larger budgets and a single budget control line and, therefore, were less siloed in their selection of topics and applicants for funding. Because the SBIR/STTR budgets are percentages of the office’s extramural research and development appropriations, appropriation changes such as refocusing funding toward research and away from demonstration projects also affect the amount of money available to SBIR/STTR programs. For example, Congress directly charged the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy with moving its research away from demonstration projects and toward early-stage basic research, a large change that affected how that office manages its entire portfolio, including SBIR/STTR.

In addition to constraints placed on the program by budget line iteming, overall budget uncertainty is a challenge. Each year, DOE must receive its appropriations before announcing funding levels for SBIR/STTR. In FY 2018, DOE received its appropriations in March and required adjustments in the number of awards planned. Some programs had to reduce the number of awards and others had to increase the number. When a budget is then increased mid-year, a larger percentage of proposals are likely to be funded because there are fewer proposals. The uncertainty about the budget throughout the year is challenging and makes budgeting for outreach and awardee follow-up extremely limited.

POST-AWARD PROCESS

A few program offices mentioned in committee interviews that once a proposal is awarded a grant, the office manages the project through interactions with the awardee team, site visits, and meetings at scientific conferences. However, most program offices said that they do not have the bandwidth (neither funds nor time) to actively manage the SBIR/STTR projects.

The SBIR/STTR Programs Office organizes a two-day meeting for each year’s (and each release’s) Phase I SBIR/STTR awardees. The principal investigator from each firm and the respective DOE program office staff are expected to attend this meeting. Staff from other DOE programs may also attend. Representatives from the Phase I small business other than the PI may also attend. According to the SBIR/STTR Programs Office, the objectives of this meeting are to provide

- face-to-face meetings between principal investigators and DOE program office staff,

- face-to-face meetings between principal investigators and the DOE Commercialization Assistance Vendor,

- networking with other small businesses, and

- information on Phase II requirements and other areas of interest such as success stories, financing, partnering with the DOE laboratories, and planning for Phase III.

COLLABORATION ACROSS OFFICES

Collaborations—ranging from topic development to award execution—offer opportunities to leverage agency resources and achieve innovative solutions. Collaboration among program offices is driven by several factors resulting in a variety of strategies across the offices’ implementation of the award process. The most common type of collaboration is inter-office collaboration. Two offices will sometimes write a topic together because of a shared interest in the research; a joint topic allows them to share the work of reviewing proposals and to pool funds. This sharing is particularly beneficial because budgets vary so substantially across offices. Programs within the Office of Science, especially Basic Energy Science, have large budgets that programs outside the Office of Science can access when research needs are shared. However, these collaborations often arise ad hoc through particularly motivated program managers willing to take on the added coordination costs to manage such endeavors. These collaborations also arise through personal relationships between managers across offices such as via those more experienced managers who have worked across multiple DOE offices. The Secretary of Energy could encourage additional use of collaborations to prioritize broader DOE priorities over individual office missions. Relaxation of Section 301 requirements would further enhance the ability of DOE to focus SBIR/STTR funding on broad DOE goals.

Another type of collaboration involves awardees. In these cases, DOE serves as a conduit for bringing small firms into relationships with other small firms, large firms, or state government agencies, universities, and national laboratories. One program office experimented with an FOA topic that required applicants to work together. Hoping that there might be synergy among several technologies, the TTM decided to ask applicants to test that hypothesis and connect the dots. To aid in this effort, he helped applicants connect with other applicants. In the end, he was very happy with the results: three small firms, each with a different expertise, collaborated to produce a coordinated result targeted for the office’s needs (see Box 3-1).

COMMERCIALIZATION ASSISTANCE

DOE offers funding for commercialization assistance for Phase I and II awardees, which can range from broad assistance in preparing an overall commercialization plan to market research, identification of strategic partners, and help with regulatory compliance. By statute, this assistance must be provided through a third party; the funding cannot be used to hire employees (U.S. Code,

2019b). Companies may select their own vendors to obtain commercialization assistance or they may use DOE’s vendor, Larta Inc. (DOE, n.d.b). If applicants do not plan to use the DOE vendor, they must include the vendor as a subcontractor or consultant in their Phase I or II application. As of FY 2019, DOE allows applicants to apply for an additional $6,500 for Phase I for commercialization activities and up to $50,000 per project in Phase II (U.S. Congress, 2019). In addition, as of FY 2019, DOE has implemented a Commercialization Assistance Pilot Program (Phase IIC) as required by law, where small businesses may apply to receive a third Phase II award to carry out further commercialization activities. Awards under this pilot program, which applies only to SBIR, are limited to a maximum of $1.1 million and must be

matched by an equal amount from a third-party investor, such as a venture capital firm, government, or individual investors (SBA, 2019).

A number of studies in the literature suggest that firms would benefit from the ability to use commercialization assistance funds to build in-house business expertise. Stuart and Ding (2006) found that commercialization outcomes were better when scientists collaborated with successful entrepreneurs. Eesley, Hsu, and Roberts (2014) showed that team diversity improves commercialization outcomes in competitive markets, and other researchers, including Nanda and Sørensen (2010), found that the probability of getting venture financing increased when employees had entrepreneurial experience.

DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

Despite some evidence of efforts by both DOE as a whole and DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office to improve outreach to (1) woman-owned firms, (b) minority-owned firms, or (c) firms in underserved areas, DOE has not measurably increased successful applications from these groups. These efforts may be failing, in part, because of limited resources for outreach, a lack of programmatic focus on leveraging diversity as a means to enhance technical and commercial merit objectives, and the relative priorities of individual program office staff.

There are opportunities for DOE to better coordinate its overall diversity and inclusion outreach with the SBIR/STTR Programs Office, requiring the individual program offices to broaden the base of proposal reviewers and to help diversify the applicant and awardee base.

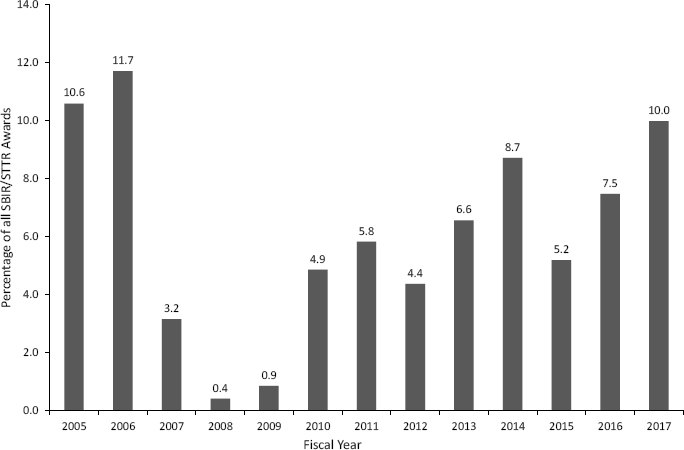

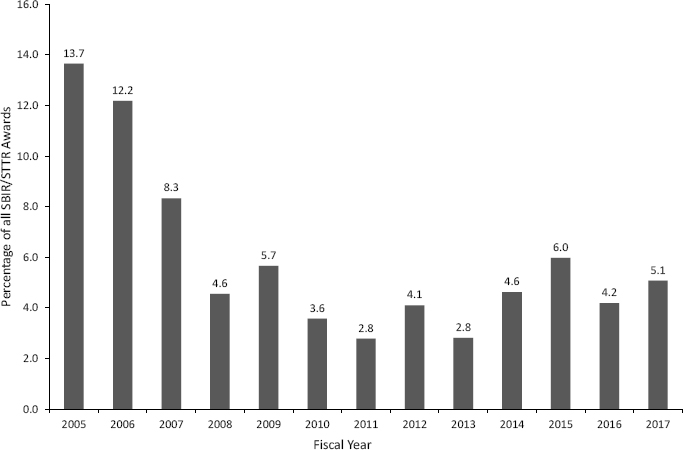

Evidence from Award Data

Recent award data reveal that the proportion of awards to woman-owned firms and firms owned by socially and economically disadvantaged (underrepresented) individuals have lagged behind pre-Great Recession levels.7 As shown in Figure 3-3, woman-owned firms accounted for approximately 12 percent of SBIR/STTR awards in FY 2006. This figure dropped to less than one percent in FY 2008 and FY 2009. Since then the overall trend has been one of recovery, but in FY 2017 woman-owned firms still only accounted for 10 percent of awards. Similarly, the proportion of total awards to underrepresented firms is well below pre-recession levels. (See Figure 3-4.) In FY 2017, only five percent of awards went to an underrepresented firm—less than half of the peak in FY 2005 of approximately 14 percent.

___________________

7 These data were collected from applicants’ indicating that they are in a “socially or economically disadvantaged” population, which is the language used in the statute. However, the committee feels that “socially and economically disadvantaged” is both confusing and pejorative. Indeed, some federal agencies have stated that underrepresented groups are undercounted, perhaps for these reasons (SBIR/STTR IPC, 2014).

SOURCE: Committee calculations based on Small Business Administration data.

NOTE: Underrepresented groups are those self-identifying as “socially and economically disadvantaged” on the application.

SOURCE: Committee calculations based on Small Business Administration data.

Viewing the data by program office reveals substantial variation in award rates to woman-owned and underrepresented firms. These variations between program offices are discussed further in Chapter 4. The percentage of awards to woman-owned firms overall averages 5.65 percent, but ranges from zero to 12.94 percent. For underrepresented groups, the distribution of awards ranges from zero to 8.91 percent.8

DOE Efforts to Improve Diversity

Improving diversity is a programmatic goal for SBIR and STTR, and efforts to improve diversity are being undertaken more broadly at DOE and its SBIR/STTR Programs Office. Efforts are also being undertaken at individual program offices, but to a lesser extent.

The Impact and Potential of Phase 0

Though no longer exclusive to woman-owned or underrepresented firms, the Phase 0 program helps first-time applicants prepare and submit high-quality Phase I proposals. Available assistance is limited and given to firms on a first-come, first-served basis. Data collected by the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office suggest that Phase 0 assistance has succeeded in helping first-time applicants win Phase 1 awards. The award rate for first-time applicants receiving Phase 0 assistance was similar to the award rate of all other applicants for FY 2015 through FY 2018. (See Table 3-2.) Available data were insufficient to allow the committee to assess the Phase 0 program’s impact on improving the diversity of successful applicants for Phase II awards, but the limited data available suggest that the program has a positive impact on new Phase I applicants.

The 2014 SBA SBIR/STTR Interagency Task Force Report Recommendations

The committee discussed a number of diversity and inclusion initiatives recommended by the 2014 SBA SBIR/STTR Interagency Task Force Report for future refinements to outreach programs to “socially disadvantaged and underserved areas.” That report defined underserved areas as the 27 states (federal districts or territories) with the lowest success in SBIR/STTR program (SBIR/STTR IPC, 2014).9 The committee found that DOE has made progress on a number of these initiatives. As shown in Table 3-5, a number of them have been implemented, but they were not mentioned in discussions with individual program offices about their efforts to expand outreach to woman-owned and minority-

___________________

8 Underlying data for these figures can be found in Chapter 4. See Tables 4-1 and 4-2.

9 The geographic distribution of awards is discussed in Chapter 4.

TABLE 3-5 Status of Implementation of Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives Suggested by the SBIR/STTR Interagency Policy Committee

| Suggested Initiative | Implemented by DOE? |

|---|---|

| Hold an annual conference in an area that is underserved; work with special interest chambers of commerce | No |

| Build a mentorship program (Mentor-Protégé Program) | Yes, but not linked to SBIR/STTR |

| Create recruitment materials | Yes |

| Educate state economic development agencies on the programs | Not directly, but it may occur through Phase 0 contractor |

| Work with universities in underserved states | Yes |

| Allocate administrative funds to enable outreach | Yes, especially via Phase 0 and Phase I awardee meeting |

| Hold regional conferences | No |

| Provide student internship programs | Yes, but not through SBIR/STTR |

| Design and disseminate webinars that are content specific | Yes |

| Create target metrics, goals, and outcomes for state participation | No, except on a limited basis |

| Use proactive email marketing | Yes |

| Utilize social media to tap the younger tech-based industry | Yes |

| Combine outreach effort amongst agencies | Yes |

| Create and fund accelerators | Yes, but only for DOE as a whole |

| Contact state and local based organizations and small business service providers | On a very limited basis |

| Upgrade website materials and content to recruit underrepresented group and woman-owned firms | Yes |

| Hold entrepreneurial boot camps for new applicants | No |

SOURCE: SBIR/STTR IPC, 2014.

owned firms. These represent a substantial effort to improve outreach to minority-owned and woman-owned firms; however, greater efforts could be taken to link DOE-wide diversity and inclusion measures to DOE’s SBIR/STTR programs.

Factors Affecting Diversity

Efforts to improve diversity undertaken at both DOE and the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office are encouraging, but several factors seem to contribute to the difficulty in addressing it successfully. Although the statute requires DOE to foster and encourage participation by socially and economically disadvantaged and woman-owned small businesses, within the program this

mandate is addressed principally at the central Programs Office level, and individual program offices are generally disengaged from diversity efforts undertaken elsewhere in DOE. Moreover, the TTMs from individual program offices stated in interviews that they did not have access to demographic data. Data on the demographics of applicants is collected by the SBIR/STTR Programs Office, as are data on the Phase 0 program, but individual program offices lack visibility into this demographic information and therefore do not maintain data on diversity nor consider it in their review and selection processes. TTMs also have no visibility into whether applicants are new to the program. There are few resources for outreach, including travel for recruitment and site visits, making it challenging to seek out diverse applicants (and reviewers). The committee was unable to gain access to application information necessary to analyze the extent to which program administration may affect the application process, including the review and selection of underrepresented groups.

Although DOE has implemented a number of the initiatives recommended in the 2014 Interagency Policy Committee report, others have not been implemented, and many of DOE’s diversity and inclusion programs are not linked to the agency’s SBIR/STTR program, representing substantial missed opportunities to coordinate DOE’s diversity and inclusion efforts. For example, there is no information on DOE’s Mentor-Protégé Program website about SBIR/STTR grantees being potential protégés, nor is there information on the SBIR/STTR program website about this opportunity, despite evidence that mentoring programs improve professional advancement outcomes (Dworkin, Maurer, and Schipani, 2012; NASEM, 2007). DOE’s recent announcement of a $4 million funding opportunity for the minority education, workforce, and training program did not mention the SBIR/STTR program. The DOE SBIR/STTR programs website does not link to DOE’s Office of Economic Impact and Diversity or the Office of Minority Economic Impact’s websites, which include links to programs that are designed to increase knowledge of and access to energy sector opportunities such as SBA’s federal and state technology partnership program. Also, neither the main page of the Office of Economic Impact and Diversity nor the Office of Minority Economic Impact website seems to have a link to the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs website. The SBIR program link on the Office of Minority Economic Impact site instead goes to an SBIR site maintained by SBA. Failure to make connections such as these diminishes the potential impact of efforts that DOE has in place to increase diversity of access to DOE programs.

The decentralized selection processes contribute to the challenge of increasing diversity. Throughout the SBIR/STTR processes, from topic selection to award selection, most individual program offices do not undertake activities that promote the diversity of the socio-economic status of owners submitting proposals or the diversity of reviewers. The vast majority of program offices view their scientific communities as fixed. Most offices view these narrowly construed communities as exogenously fixed and the only source of reviewers, input on topics and proposals, and applicants. If outreach is conducted, it is through the

professional associations that do not convene in underrepresented communities or in underserved states.

One area of consistency revealed in the committee’s work—one that does not benefit the program goal of improving diversity—is that all programs reported focusing solely on the technical merit and technical capabilities of the reviewers and awardees. The implied argument was that geographic, ethnic, racial, gender, or organizational diversity contradicted technical merit rather than enhanced the quality and creativity of the outcome. As noted, most offices believe their community is a finite and relatively small group of scientists with specific technical expertise. TTMs see their communities as fixed and comprising mainly research scientists in the disciplinary areas with which their scientific mission aligns, in part because of limited resources for outreach and the low priority of the SBIR/STTR program relative to their other programs. Exceptions include outreach efforts by the Office of Fossil Energy to attract more applications from particularly underserved areas like West Virginia. Also, larger offices encompassing wider disciplinary areas of science comprise a larger community and thus are more likely to have a somewhat more diverse group of scientists. The committee believes that broadening how each office depicts its respective communities would widen the diversity of viewpoints and perspective and increase novelty, innovation, and creativity.

The narrow definition of community considered by the technical focus of the program offices is also reflected in the selection of reviewers and can bias the peer review process. The committee found that the majority of reviewers for applications come from national labs (46 percent) or universities (32 percent), and, as noted earlier, these potential reviewers are more likely to be male and white. At national labs, for example, women and underrepresented groups that DOE is seeking to reach comprise only a small share of leadership or research and technical management positions.10 Similarly, at universities underrepresented minorities comprise less than 10 percent and women comprise 32 percent of all full professors (IES, 2019). For engineering departments these numbers are even lower, with women faculty of any rank comprising 16 percent of the faculty, African American faculty 2.3 percent, and Latino faculty 3.6 percent (ASEE, 2016). A 2007 National Academies committee found that:

A substantial body of evidence establishes that most people—men and women—hold implicit biases. Decades of cognitive psychology research reveals that most of us carry prejudices of which we are unaware but that nonetheless play a large role in our evaluations of people and their work (NAS/NAE/IOM, 2007).

___________________

10 Women comprise approximately 25 percent of senior leadership positions at national labs and 18 percent of research/technical management positions. Underrepresented minorities comprise about 8 percent of senior leadership positions and research/technical management positions (National Laboratories, 2020).

Among the research cited in the report is study of peer-review scores for postdoctoral fellowships in Sweden. The Swedish study found that “peer reviewers overestimated male achievements and/or underestimated female performance”—and that “a female applicant had to be 2.5 times more productive than the average male applicant to receive the same competence score” (Wennerås and Wold, 1997). Similarly, a recent study found a persistent bias against female entrepreneurs (Wood Brooks et al., 2014). Without access to application information, the committee was unable to evaluate the impact of unconscious or implicit bias on the DOE SBIR/STTR selection process, but increasing the diversity of review pools can be expected to help mitigate bias and can send positive signals that the programs are accessible to underrepresented groups.

The SBIR/STTR Programs Office should provide guidance documents to each individual program office regarding the value of taking steps to ensure more diverse applicant and reviewer pools, with the goal of increasing the creativity and novelty of the proposals. In working with each program office to create action plans that more explicitly advance these considerations, each office’s stakeholder community will become more inclusive, which will not only ensure more novel and creative proposals but also a greater staff and reviewer capacity to process such proposals in an effective and timely fashion. Overall program information and specific information on FOAs can be communicated to a more diverse group of applicants through state agencies and other regional actors and publicized at regional conferences important to the field, and FOAs can also be publicized in media popular with underrepresented groups. DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office should also provide guidance to the individual offices regarding strategies for broadening the reviewer pool and should ensure that reviewer pools do become more diverse. For example, recruiting graduate students or postdoctoral students to serve as reviewers offers an opportunity to engage a more diverse population of reviewers than recruiting tenured faculty or national lab managers, while still maintaining a substantial focus on technical expertise. DOE can strengthen outreach efforts to recruit reviewers from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), and Tribal Colleges. Finally, because some reviewers may not hold positions that compensate them during time spent acting as a reviewer and may therefore be unwilling to serve as a reviewer, DOE may consider encouraging offices to pay reviewers if they are having difficulty diversifying their reviewer pools.

The development of and tapping into a more diverse community offers promise. A few offices noted that expanding their communities increased the diversity of expertise and ideas. In one example provided to the committee, when the research needs of an office changed in response to the demands of the mission, this led to an FOA that received no applications. The office reached out to new scholarly communities and successfully accessed the expertise it required.

DOE has recently taken some steps to foster a more diverse workforce that could also lead to a more diverse set of grantees over the long term. There is evidence of a positive association between agency workforce diversity and Phase II funding for Phase I grantees. Joshi, Inouye, and Robinson (2018) examined

SBIR/STTR awards for all agencies from 2001 through 2011 and found that an increase in racial/ethnic and gender diversity in an agency’s workforce leads to a substantial increase in the rate at which minority- or woman-owned firms are awarded Phase II awards. DOE’s Office of Economic Impact and Diversity has announced a new program for FY 2020 designed to increase STEM education in minority-serving institutions, strengthen links between its national labs and minority-serving institutions, and provide technical assistance and training (DOE, 2019).

Retaining funding levels for SBIR and STTR is also important for meeting the goals of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Joshi, Inouye, and Robinson (2018) showed that funding for SBIR and STTR tends to have a disproportionately larger impact on minority-owned and woman-owned firms than other types of firms. This may be because these entrepreneurs may be facing greater financing constraints than other entrepreneurs.

IN CLOSING

There is considerable consistency across the DOE program offices in their adherence to the formal processes and procedures articulated by the DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office. However, because individual program offices view the SBIR/STTR programs through the lens of their unique scientific missions, they differ in how they identify their research and development needs and how they use small businesses to meet those needs. These scientific priorities also influence how offices view commercialization. For example, some program offices focus on obtaining specialized components for advancing science and regard that as successful commercialization. In these instances, there may be few firms with the appropriate expertise, hence those offices have a greater reliance on small firms that win multiple SBIR/STTR awards.

While the processes used across all offices share some similarities, they also show differences reflective of the flexibility that SBIR/STTR offers for participating agencies to use the program and small business participants to meet the offices’ own missions and goals. When developing solicitation topics, for example, some offices have uniform policies for all staff while others allow staff to tailor the process to best suit the needs of the programs they manage. In general, all offices rely heavily on the people and organizations they consider the most proximate stakeholders to suggest what needs they should address and, from that, craft topics accordingly. Similarly, to identify potential peer reviewers to assess applications, many program offices search only within this stakeholder community.

Despite some evidence of efforts by both DOE as a whole and DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office to improve outreach to woman-owned firms, minority-owned firms, or firms in underserved areas, DOE has not measurably increased successful applications from these groups. There are opportunities for DOE to better coordinate its overall diversity and inclusion outreach with the SBIR/STTR Programs Office, requiring the individual program offices to broaden

the base of proposal reviewers and to help diversify the applicant and awardee base.

FINDINGS

Finding 3.1: The solicitation process promotes the mission of DOE, and there is fidelity to the prescribed SBIR/STTR guidelines. The review and solicitation process is clearly articulated and transparent to program staff and applicants.

Finding 3.2: The SBIR/STTR programs are run as R&D competitive grant programs with inadequate effort placed on expanding the perceived community to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion in the applicant pool. Although efforts by the SBIR/STTR Programs Office, which include Phase 0 and webinars, have increased the quality of applications, the topic, reviewer, and awardee selection processes limit the diversity of program participants.

Finding 3.3: Outreach to potential applicants who have never done business with DOE and its SBIR/STTR programs is limited. This may give an advantage to labs, universities, and small businesses that receive other grants or contracts with DOE.

Finding 3.4: With the exception of DOE’s approach to addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion, the program is flexible, with collaborations across program offices, applicants, and state and local governments, although strict adherence to budget control lines may inhibit that flexibility.

Finding 3.5: There is a tension behind the speed at which applications are processed (required 90 days between application deadline and award selection) and the number of applications received. This tension may encourage some program offices to limit applications and outreach to new applicants.

Finding 3.6: The statutory requirement to use external vendors for commercialization assistance may hinder small business commercialization prospects and business development in the long run. Moreover, because Phase II applicants are judged, in part, on their commercialization plan, the commercialization assistance in Phase II is given too late for an applicant to use to develop a robust commercialization plan.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 3.1: The DOE SBIR/STTR Programs Office should actively take steps to ensure the diversity of the reviewer pools as a means to increase the diversity of the applicant pool.

Recommendation 3.2: The Secretary of Energy should enlist outside experts in diversity to facilitate guidelines and processes for achieving greater diversity within DOE, which will carry through to DOE’s SBIR/STTR programs. Outside experts can facilitate a framework for providing agreed-upon observable and measurable outcomes to track diversity, clear processes that use these outcomes to influence decision making, and better linkages between diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts across DOE.

Recommendation 3.3: Each program office should share and explain exemplary proposals to DOE’s SBIR/STTR Programs Office. The SBIR/STTR Programs Office should communicate information on exemplary proposals to state agencies and other regional actors and publicize this information at regional conferences important to the field. This can form a part of general outreach to these entities to increase awareness of the SBIR/STTR funding opportunity.

Recommendation 3.4: Congress should consider allowing DOE greater flexibility in allocating funding for SBIR/STTR programs across different offices in DOE to maximize the broad match between small businesses and DOE’s mission to ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental, and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions.

ANNEX

DOE Program Managers Interview Questions and List of Attendees

-

Goals - What are your goals for the SBIR/STTR programs from your vantage point as a program manager?

- What does success look like? How would you know it if you saw it?

- What are examples of success?

- How long have you worked on the SBIR/STTR program, and what percentage of your time is allocated to SBIR/STTR?

-

Can you briefly gives us an overview of the SBIR/STTR processes from your vantage point as a program/portfolio/topic manager?

-

How are topics developed? Who develops them?

- What is your relationship with the national labs?

- Can firms or industry propose ideas?

- Are there incentives for choosing certain topics over others? (e.g. roadmap)

-

How are reviewers selected?

- How many of the reviewers come from within their program? How often do they serve on the review panels?

-

How are awardees selected?

- What are key factors looked for in selection of a company or technology?

- How much discretion do you exercise in selecting awardees?

- What is the primary source of accountability or oversight?

-

Other questions

- What are tradeoffs between administration and evaluation?

- Do you contract with big firms? If so, what are the challenges?

- Are you a convener—bringing people together and then getting out of the way—or an intermediary/high touch matchmaker?

-

How are topics developed? Who develops them?

- What is the role of Congress and the administration from your vantage point as a program manager?

-

Based on your experience, which companies stand out?

- How is commercialization potential evaluated?

- What kinds of DOE or SBIR/STTR commercialization services are available for applicants? For awardees?

- Have you had any commercialization home runs?

- Do you recommend that we talk to certain companies, and why?

- If you could change one thing (or more than one thing) about the SBIR/STTR programs, what would that be?

TABLE 3-6 DOE Program Managers Interview Dates and Participants

| DOE Office | Interview Date | DOE Attendees |

|---|---|---|

| Office of Science | ||

| Office of Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) | 6/25/2018 | Richard Carlson |

| Basic Energy Sciences (BES) | 6/25/2018 | Elaine Lessner Natalia Melcer |

| Biological and Environmental Research (BER) | 6/25/2018 | Prem Srivastava Amy Swain David Lesmes Ramana Madupu |

| Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) | 6/25/2018 | Barry Sullivan Eric Colby Altaf Carim John Boger |

| High Energy Physics (HEP) | 6/26/2018 | Ken Marken |

| Nuclear Physics (NP) | 5/23/2018 | Michelle Shinn Manouchehr Farkhondeh |

| Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation (DNN) | 5/23/2018 | Victoria Franques Lt. Col. Benjamin Miller Leslie Casey |

| Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) | 5/23/2018 | Tina Marie Kaarsberg |

| Environmental Management (EM) | 6/25/2018 | Skip Chamberlin Latrincy Bates |

| Fossil Energy (FE) | 7/12/2018 | Doug Archer Maria Reidpath Kim Jai-Woh William Fincham Pat Rawls John Wimer |

| Nuclear Energy (NE) | 6/26/2018 | Kenny Osborne Derick Ogg |

| Office of Electricity (OE) | 6/25/2018 | Kerry Cheung |

This page intentionally left blank.