Summary1

Since 2004, the U.S. government has supported the global response to HIV/AIDS through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Working through many partners, including country governments, PEPFAR supports a range of activities, such as direct service provision, programmatic support, technical assistance, health systems strengthening, and policy facilitation.

The Republic of Rwanda, a PEPFAR partner country since the initiative began, has made gains in its HIV response, including increased access to and coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and decreased HIV prevalence. However, a persistent shortage in human resources for health (HRH) affects the health of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and the entire Rwandan population. This challenge is consistent with a balancing act commonly faced in the global response to HIV, which requires policy, funding, and programmatic decision making around how to improve health care to meet HIV-specific needs—the core of PEPFAR’s mission—within a health system that lacks sufficient capacity to meet either HIV-specific health needs or those of the broader population.

Recognizing HRH capabilities as a foundational challenge for the health system and the response to HIV, the Government of Rwanda worked with PEPFAR and other partners to develop a program to strengthen institutional capacity in health professional education and thereby increase the production of high-quality health workers. The HRH Program was origi-

___________________

1 This summary does not include references. Citations to support the text and conclusions herein are provided in the body of the report.

nally designed to address four barriers to the provision of adequate care: a shortage of skilled health workers, poor quality of health worker education, inadequate infrastructure and equipment for health worker training, and inadequate management across different health facilities. The Ministry of Health (MOH), which implemented the Program, partnered with U.S. medical, nursing, dental, and public health training institutions to build capacity at the University of Rwanda College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CMHS). Activities centered around a twinning program that paired Rwandan and U.S. faculty and health professionals, new specialty training programs and curricula, and investments in teaching hospitals and learning environments.

Funding came primarily from PEPFAR through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Other funders included the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the MOH; and, to a lesser extent, other entities. The Program was fully managed by the Government of Rwanda and was designed to run from 2011 through 2019. PEPFAR initiated funding in 2012. In 2015, PEPFAR adopted a new strategy focused on high-burden geographic areas and key populations, resulting in a reconfiguration of its HIV portfolio in Rwanda and a decision to cease funding the Program, which was determined no longer core to its programming strategy. The last disbursement for the Program from PEPFAR was in 2017.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

The Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) was asked, through a single-source request for application from CDC, to evaluate the HRH Program. The overarching purpose of the request was to understand how PEPFAR’s investment affected morbidity and mortality outcomes for PLHIV. The National Academies was asked, to the extent feasible, to address four objectives:

- Describe PEPFAR investments in HRH in Rwanda over time, including its support for MOH efforts to address HRH needs as well as the broader context in which these investments were made.

- Describe PEPFAR-supported HRH activities in Rwanda in relation to programmatic priorities, outputs, and outcomes.

- Examine the impact of PEPFAR funding for the HRH Program on HRH outcomes and on patient- or population-level HIV-related outcomes.

- Provide recommendations to inform future HRH investments that support PLHIV and to advance PEPFAR’s mission.

EVALUATION APPROACH

To meet this charge, the expert committee convened by the National Academies sought to develop an approach that would integrate the evaluation objectives to examine the Program in relation to its priorities, to strengthen institutional capacity to produce high-quality health workers, and to examine its impact on outcomes for PLHIV. The evaluation applied a retrospective mixed-methods design, drawing on document review, qualitative interviews, and secondary analysis of quantitative data. Eighty-seven interviews were conducted with program administrators; U.S. institution faculty; professional associations and councils; University of Rwanda faculty, students, and administrators; health care workers; and other stakeholders. CDC and PEPFAR determined that participation in interviews would present a conflict of interest; therefore, the perspectives of current staff from the donor are not represented in this analysis, a notable gap. Secondary quantitative data collection and analysis used publicly available HRH and HIV data and data provided by the University of Rwanda and the MOH. Some of the requested data were not available, which limited the analysis that could be performed.

The committee approached the request to assess the impact of PEPFAR’s investments from the perspective of the Program’s plausible contribution to HRH and HIV-related outcomes. This contribution was conceptualized through a theoretical causal pathway for how programmatic activities and resulting changes in HRH outputs could reasonably be expected to contribute to intermediate HRH and health outcomes for PLHIV. The well-documented relationship between HRH outcomes and patient-level outcomes was used to bridge the gap between the Program’s original stated intentions and this evaluation’s objectives. The posited pathway to impact is that a stronger health workforce that is able to meet the health needs of the population can be expected, along with other factors, to generate improved public health and health care delivery systems. The combination of a functioning health system with an effective workforce results in better-quality services. This contributes to improved health outcomes in general, including for PLHIV, and to improved HIV-related outcomes, such as decreased incidence, mortality, and morbidity.

The approach of assessing plausible contribution to impact is an accepted standard as an effective methodology to retrospectively assess a health systems strengthening program such as the Program. Directly attributing impact to the Program was not feasible for a number of reasons. First, the retrospective nature of the evaluation limited the options for designing an examination of impact. Second, the lack of an appropriate comparator made determining attribution unrealistic. Rwanda’s unique context relative to other East African countries, the role of the University of Rwanda

as the singular public institution for health professional education, and the widespread placement of HRH Program trainees meant there was no intervention-free setting, in Rwanda or in a comparable country, that could enable a comparison design to facilitate attribution analysis.

Third, it was not possible to disentangle the effects of Program activities from the multitude of other factors, both within and external to the health system, that contributed to HRH and HIV-related outcomes. Fourth, Rwanda had made notable HIV-related achievements before the Program began. With a relatively high baseline for key HIV indicators, any effects would be of a relatively small magnitude, making it challenging to conduct a before-and-after comparison that could isolate the impact of this Program, which focused on one aspect of an integrated health system in which multiple factors play a role in people’s access to high-quality HIV care.

Finally, the proximal timing of this evaluation relative to the end of PEPFAR’s funding limited the ability to detect potential impact on population-level HIV indicators such as incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality. Any effects on these outcomes would be expected to manifest much later; investments in health professional education can take years to have an effect on patient- and population-level outcomes, given the time required for training and for trainees to enter the health system in the necessary volume and duration.

The committee has crafted a report to be useful to PEPFAR as it reflects on its investments in the Program. The report also contains valuable information for the Government of Rwanda as it continues strengthening its health workforce and health system to address the evolving needs of its population, including with respect to HIV. In addition, the report can inform other stakeholders in Rwanda engaged in that work, such as other funders, health professional educational institutions, professional societies, patient advocacy groups, and other civil society organizations. Furthermore, there are lessons for stakeholders in other countries aiming to strengthen health systems and the health workforce through professional education.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

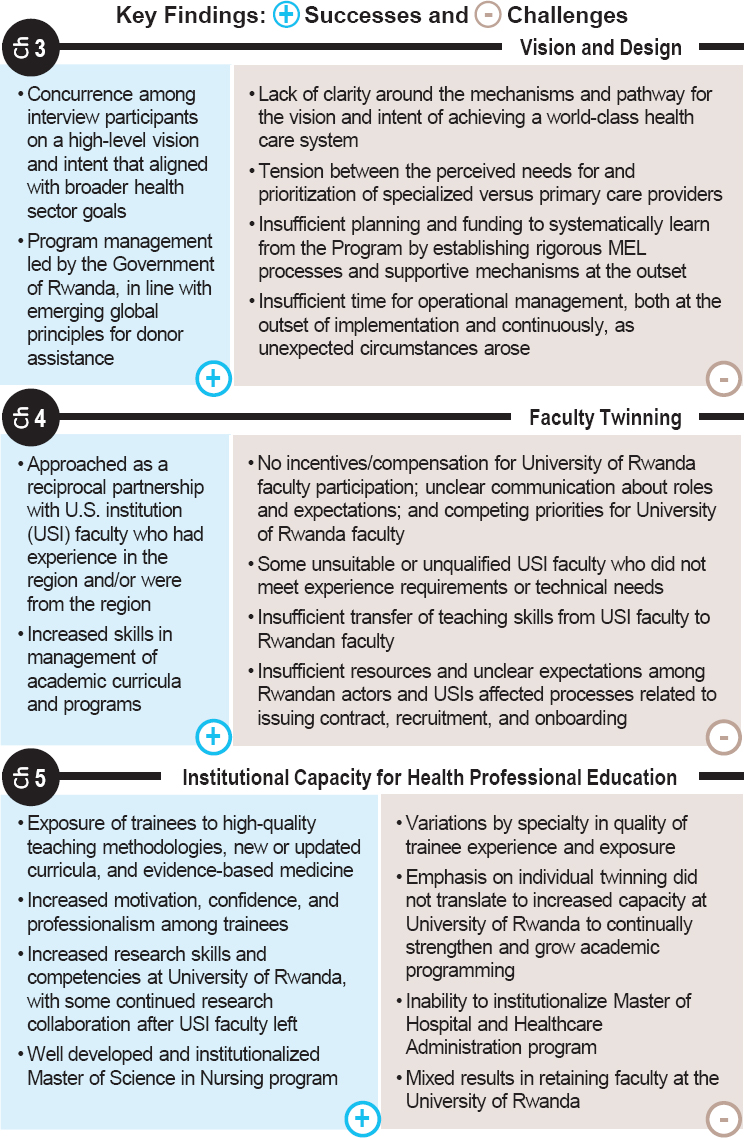

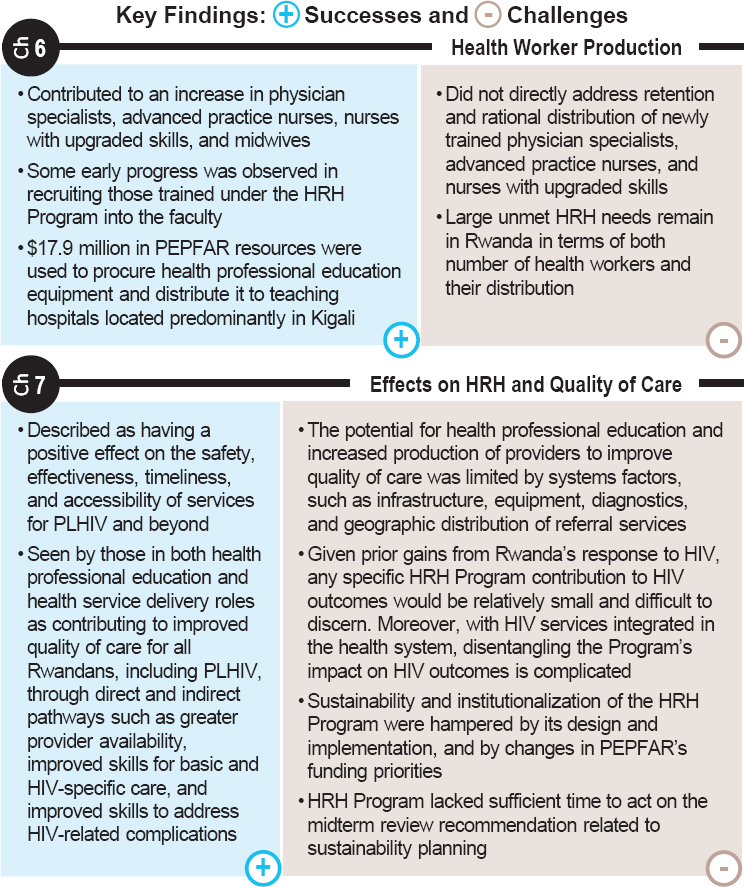

The evaluation’s overarching findings are visualized in Figure S-1, organized according to the report chapters where they are presented in detail. Based on findings about both the successes achieved and the challenges experienced in the Program, the committee was able to draw conclusions about its implementation and its effects.

For the reasons described above, it would not be reasonable to expect investments in the broad, foundational capacity building represented by the HRH Program to result in large changes in HIV-specific, population-level outcomes within the time frame of this evaluation. Such investments are not

designed to achieve relatively short-term, large-scale shifts in population disease outcomes and therefore may not be the appropriate choice if that is the singular intention of an investment.

Concurrent with the HRH Program, Rwanda experienced decreasing prevalence, increasing access to and coverage of ART, and increasing percentages of adults who know their status, are on ART, and have reached

viral suppression. It would be reasonable to expect, in combination with a multitude of other factors, that some initial improvements in quality and availability of care resulting from the Program could contribute to such population-level outcomes. It would not be possible to isolate, quantify, and attribute such effects to this Program without a prospective evaluation design and available data matched to that purpose.

Nonetheless, this evaluation was able to draw some conclusions with respect to the Program’s effects on PLHIV. Analysis of the available data suggests that improved quality of care links Program activities to programmatic impact—namely, improved overall health outcomes and HIV-related outcomes. Respondents with roles in both health professional education and health service delivery perceived the Program as contributing to improved quality of care for all Rwandans, including PLHIV, through direct and indirect pathways, such as greater availability of providers, improved skills for basic and HIV-specific care, and improved skills to address HIV-related complications. The Program was described as having a positive effect on the safety, effectiveness, timeliness, and accessibility of services for PLHIV. The potential for health professional education and increased production of providers to improve quality of care is limited by systems factors, such as infrastructure, equipment, diagnostics, and geographic distribution of referral services.

With respect to the goal to expand the quantity and quality of the health workforce in Rwanda, the Program achieved many successes. Exposure to high-quality teaching from faculty recruited through partnerships with U.S. institutions laid the groundwork for trainees to provide high-quality care, take on leadership roles, and train the next generation of health professionals. The Program improved the overall quality of professional preparation as a result of institutional capacity outcomes, such as new programs and new or upgraded curricula, and increased the quantity and quality of different cadres of health professionals, especially in nursing, midwifery, and selected medical specialties. It also increased trainees’ research capacity, motivation as they entered the health workforce, and professional development opportunities. An improved relationship between the MOH and the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the strengthening of professional associations and professional councils, are results that could provide momentum to sustain and continue building institutional capacity. This evaluation could not speak to sustainability achieved through these gains because of how little time has elapsed since the end of PEPFAR investments.

The complexity of the HRH Program and the system it aimed to strengthen meant these successes were accompanied by challenges, which together offer lessons for future programming. Challenges with respect to the ambitious goals of increasing institutional capacity for health professional education included operational issues, variable implementation of

the twinning approach that paired University of Rwanda and external faculty, insufficient design around the mechanisms intended to achieve the Program’s full vision, and inadequate planning for the complexity of structural changes necessary to achieve and sustain improvements in health professional education. There was also a tension between the perceived need for specialized care and the perceived need for greater primary care. Unmet HRH needs remain, in terms of both sheer numbers of professionals and their geographic distribution.

When it was funded, the Program represented an uncommon, although not unique, donor approach to strengthening HRH capacity through a large investment in building capacity in health professional education institutions. This was a departure from PEPFAR’s usual operational model between funder and government. Although it was not a requirement of the first phase of PEPFAR funding, without a clearly defined monitoring and evaluation plan at the initiation of the Program, there was a missed opportunity to systematically learn both how to strengthen HRH capacity, and how governments, other stakeholders, and external donors could together balance disease-specific priorities and broader health system needs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HIV AND HUMAN RESOURCES FOR HEALTH PROGRAMMING

As Rwanda and other countries make laudable progress toward controlling the epidemic and improving treatment coverage, more PLHIV are living longer, with health needs that lie at the intersections of managing HIV and its complications over time, managing comorbid conditions, and attending to quality of life. Comprehensive support for the needs of PLHIV is increasingly dependent on the strength of the entire health system. Therefore, to advance its mission, it is in PEPFAR’s interest to support comprehensive health system strengthening through long-term strategies that are well coordinated with other donor and government investments. To be most effective, these would not be designed around a specific disease, but it is also reasonable for disease-specific funders to expect their investments in broader efforts to have effects that contribute, albeit not exclusively, to disease-focused outcomes. Investments can contribute to programs designed to optimize and monitor disease-specific effects without interfering with broader systems effects. Such investments have the greatest potential to yield sustainable results.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee navigated this balancing act between disease specificity and systems strengthening in response to its task to make recommendations to “inform future HRH investments that support PLHIV and to advance

PEPFAR’s mission.” The recommendations reflect a suggestion that when PEPFAR and other funders with a disease-specific mandate invest in HRH strengthening, they take a “diagonal” approach, seeking the intersection between vertical (disease-specific) needs and outcomes and horizontal (systemwide) efforts that can help meet those needs. The recommendations seek to make that intersection more balanced, achievable, and measurable for future investments in HRH. The recommendations offer a framework for designing and implementing future efforts to strengthen the health workforce and the provision of services for PLHIV.

Building on the successes from this Program, reflecting on the lessons learned, and recognizing the inherent complexity of HRH, these recommendations are organized around five key areas:

- The need to codesign programming with diverse relevant stakeholders;

- The importance of taking a complex systems approach;

- The value of planning and adaptive management;

- The importance of selecting an appropriate model (or components) for improving health professional education; and

- The centrality of a proactive and multifaceted approach to monitoring, evaluation, and learning.

Program Codesign

Across respondents and program documents, there was concurrence on the Program’s high-level vision, which aligned with broader health-sector goals, but there was lack of clarity among stakeholders around the mechanisms and pathways for achieving this vision. This had implications for design, implementation, and sustainability planning and was compounded by participating institutions’ differing administrative practices.

Recommendation 1: Funders investing in strengthening human resources for health should support a codesign model through a process that engages representatives from diverse stakeholders as the designers,2 including funders, program administrators, implementers, regulatory bodies, and those who will use or benefit from the funded activities.

To ensure a feasible program that reflects reality and responds to the need, a collaborative, bottom-up design process that includes funders, government representatives across relevant sectors, implementers, and beneficia-

___________________

2 Latter recommendations that actions be taken by HRH program designers refer to this group of diverse stakeholders.

ries (in this case, faculty, students, and patients) can be an effective approach. The 2008 Accra Agenda and 2011 Busan Partnership Agreement highlight the importance of South-to-South partnerships3 and the multistakeholder model for development. This model encourages national and subnational governments to play a greater role in oversight and accountability, civil society organizations to contribute to policy and implementation oversight, and the private sector to explore how to advance mutually reinforcing development outcomes.

Funding agencies’ emerging use of cocreation models also provides a way to further include diverse stakeholders (such as implementing partners, host-country governments, private-sector representatives, and local organizations and experts) to lead activity design and structuring, enhancing local ownership, and increasing the likelihood of achieving the results.

Design with a Complex Systems Thinking Lens

Health systems are complex and nonlinear, requiring cooperation across sectors and organizational units. The HRH Program underestimated this complexity. This was illustrated by the missed opportunity to actively engage the MOE and the University of Rwanda in the design and early implementation phases. This engagement subsequently improved in the course of operationalizing the Program. Another underestimation of complexity relates to time frame. Building a health workforce and being able to observe the resulting impact on HIV-related morbidity and mortality takes decades, a reality that was not reflected in the relatively short duration of PEPFAR’s investments.

Recommendation 2: Designers of programs to strengthen human resources for health should employ a complex systems thinking lens, including multisectoral approaches that mix top-down and bottom-up models with long-term flexible funding that can support both the immediate needs of a health system and longer-term issues, such as the retention of health workers.

Applying complex systems thinking can change how program designers conceive of health system challenges, the questions they ask about how to improve the system, and their understanding of the factors that support or hinder improvement. A systems approach also recognizes that the health system is nested within a larger government, and the health workforce is

___________________

3 This term describes collaboration among two or more low- and middle-income countries involving knowledge exchange and support that enable them to work toward their development goals.

nested within regional labor markets, necessitating collaboration and coordination across sectors and among governmental and nongovernmental institutions.

For the health workforce, a systematic approach needs to be adopted in the context of the labor market, taking into account health worker supply and demand and how those interact dynamically with the need for health services, the health needs of the whole population, and national goals for access and coverage. Program design should not only create new health workers but also redress factors that undermine the capacity of the existing workforce. A labor market lens that considers both supply and demand can leverage existing investments in health professional education and correct imbalances in supply, which are often due to the dominance of demand-side forces. Government health workforce production policies should be coordinated with policies in the education and labor sectors, as well as policies about absorbing newly educated health workers into the health sector. Governments should also regulate the private sector to ensure quality of care and appropriate, equitable health worker distribution. The private sector should drive innovation, such as public–private models for strengthening the workforce in response to market opportunities and other settings in which governments cannot effectively respond.

To align with the time frame needed to build an HRH pipeline, funding strategies should be long term and integrated with a recipient country’s larger strategy. Funding needs to outlast donor countries’ political terms and agendas and typical donor funding cycles, with a built-in transition to sustained country-led financing. Donors should accommodate this, to the extent feasible, with greater flexibility in shaping and adapting program budgets and processes. Donors should enable longer-term coordinated funding and incorporate practices such as an inception period in procurement processes; increased flexibility in revising objectives, targets, and outputs; and allowing a proportion of the program’s budget for adapting strategies and development programming based on changing conditions. At the same time, donor expectations for revising programming should be clearly outlined for recipients, with transparency infused throughout the process. As partners, governments should focus on assembling diversified funding sources and convening public- and private-sector actors with vested interests in national HRH goals to coordinate financing initiatives and reduce reliance on donor funding, which can be volatile.

Planning and Adaptive Management

Overall management of the HRH Program was challenged by a lack of clarity around the mechanisms and pathways for achieving its vision and by

the lack of time and capacity allocated for operational management, both at its outset and throughout implementation.

Recommendation 3: To maximize the effectiveness of investments in human resources for health, which inherently require change within a complex system, designers of programs to strengthen human resources for health should spend time before implementation to establish a shared vision, proposed mechanisms to achieve that vision, and an operational plan that takes an adaptive management approach.

Donors increasingly recognize the need for adaptability to make effective investments. Those funding HRH programs need to embrace this approach, including clarity of rationale and specificity of design at the outset, and learning-based adjustments as implementation proceeds. Program assessment and accountability should be responsive to realities encountered during implementation, rather than being narrowly based on adherence to the original design.

Adaptive management is an intentional approach to making decisions and adjusting programmatic activities in response to emerging information, unintended consequences, and unexpected challenges. Key principles include reframing program design and implementation from a linear to a more iterative process, building in flexible management structures, identifying periodic windows to assess and reconsider implementation decisions, and creating feedback loops between decision making and real-time information on the program’s progress and struggles. Adaptive management is underpinned by robust, continuous, and usable data that are rapidly analyzed and debated to facilitate informed decision making within a culture of improvement. A critical aspect is coordinated consultation across departments and functions, balanced against defined roles and responsibilities for decision making and effective action. As discussed in Recommendation 6, HRH programs should include a comprehensive approach to monitoring, evaluation, and learning as an integrated responsibility not only for designated staff, but also for other technical and operational staff.

Models for Improving Health Professional Education

Building capacity in the HRH Program occurred predominantly through an academic consortium comprising U.S. institutions that contracted faculty to be paired in “twinning” relationships with University of Rwanda faculty. These faculty also provided direct teaching and clinical services. The Program had mixed results with twinning, predominantly due to varied experiences in design, management, and implementation across specialties and nursing. Strengths included bringing external experts to

the University of Rwanda, which improved the ability of Rwandan faculty to manage programs, enabled an increase in the number of trainees, and built lasting U.S. and Rwandan partnerships for research and faculty professional development. That the twinning program did not fully meet its objective of widespread, institutionalized teaching and clinical skills transfer was due to a lack of clarity in its design and operational challenges in its implementation.

Recommendation 4: Designers of programs to strengthen human resources for health should, on the basis of the vision and goals of the program, evaluate different models for improving health professional education that best fit the workforce needs to be met and the local structural and contextual considerations for human resource capacity building.

The HRH Program used an individual twinning model to build faculty and institutional capacity for health professional education. Other models are available and should be evaluated before selection, based on the programmatic goals and vision and the needs of the health workforce. Efforts to institutionalize improvement require the following:

- Structures to support faculty in the longer term;

- Availability of faculty to commit additional health professional education development;

- Adequate time and funding for accreditation processes, research skills building, and other aspects of health professional education beyond teaching skills;

- Long-term institutional partnerships; and

- Less time-intensive teaching models.

Program designers should consider the application of technology for education and skills building and the potential for blended learning (combining technology with traditional face-to-face approaches).

For programs that select twinning models to improve health professional education, this evaluation offers several lessons for potential improvements, depending on the time frame, goals, and desired type of skills transfer.

Recommendation 5: Designers of programs to strengthen human resources for health who want to employ paired partnerships, or “twinning,” should identify clear objectives and consider an integrated design, with twinning partnerships at both the institutional and individual levels that are based, to the extent available, on best practice guidelines.

Institutional twinning comprises partnerships between institutions, which may include aspects that are operationalized through individual relationships between participating faculty or practitioners. The World Health Organization (WHO), the European Union’s ESTHER4 Alliance for Global Health Partnerships, and the United Kingdom’s Tropical Health Education Trust (THET) have all employed institutional twinning partnerships and have well-developed definitions, practices, processes, and tools for designing, implementing, and assessing the effectiveness of institutional twinning models.

Individual twinning comprises partnerships based on pairing individuals in peer-to-peer, mentoring, or trainer–trainee relationships. Their effectiveness can be enhanced when carried out under the umbrella of an effective institutional partnership. Operationalizing peer-to-peer twinning support should consider methods such as blending in-person and distance learning or bidirectional international placements of shorter durations. Using ratios greater than one-to-one for partnering between external and local twins could be another effective approach.

There are two key themes that should be considered when strengthening health professional education institutions via any twinning model. First, the approach should be adapted to the funding context and the country needs. It is imperative to consider the cultural, linguistic, and historical dynamics involved in twinning relationships, by preparing and coaching twins and prioritizing regional twinning when possible. Second, twinning should be considered a partnership. Partners should formally agree to predefined roles that are shared transparently with the individuals involved before initiating the relationship. Roles could include exchanging knowledge while sharing teaching or clinical responsibilities, mentorship, training, or a mix of these.

Programs that develop robust plans for learning, as discussed in Recommendation 6, will make a much-needed contribution to the knowledge base on twinning methodologies and their effectiveness.

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning

While there was recognition that the HRH Program presented an unprecedented opportunity at the intersection between health systems strengthening and HIV, there was insufficient planning and investment to learn systematically from the endeavor through monitoring and evaluation support established at the outset.

___________________

4 The organization’s original name was Ensemble pour une solidarité thérapeutique hospitalière en réseau (ESTHER) or Network for Therapeutic Solidarity in Hospitals, as it was known in English.

Recommendation 6: Designers of programs to strengthen human resources for health should craft and resource a robust and rigorous framework for monitoring, evaluation, and learning that fits the complex, interconnected, and often changing nature of health systems, and that balances costs and feasibility with transparency, accountability, and learning.

Rigorous monitoring, evaluation, and learning should begin in the design phase by drawing on a wide base of evidence to increase relevance and effectiveness in the country’s current context. Elements include background research on relevant models in the region, social or organizational network analysis of existing actors working to improve HRH, or the use of available tools and guidelines, such as those compiled by WHO, to identify gaps and estimate specific needs within the health workforce, including HIV-specific workforce needs.

A baseline needs assessment should inform how to balance competing priorities, such as emphasis on specialized or primary care. With respect to HIV/AIDS, a long-term design for HRH investments needs to reflect the anticipated future of the epidemic—strengthening a health system to be able to care for an aging PLHIV population. The design of HRH programs should consider the anticipated evolution of workforce needs as the burden of disease shifts over time. In Rwanda, for example, many of the documented emerging clinical needs fall outside the realm of HIV/AIDS. Comprehensive, coordinated assessment will enable future HRH investments to identify common barriers and opportunities, as well as those specific to diseases and specialties.

Program design should also include ongoing mixed-methods monitoring with built-in pause points for actionable learning. Key components include a priori selection or development of indicators to evaluate the program’s effectiveness, efficiency, and outcomes and a funded plan for dissemination and use of findings. Ongoing monitoring should draw on or improve existing government data systems to minimize burden and ensure data systems also benefit from the investments. Periodic evaluations or special studies that look at particular aspects of the program could provide a useful complement to routine, ongoing data collection and use.

Systematically designed plans for monitoring, evaluation, and learning with sufficient funding and staffing would enrich understanding of what it takes to build, implement, and sustain an effective HRH program, as well as the program’s potential impact. Early process indicators can support course corrections. Measures selected and timed appropriately can document longer-term effects of systems change. If an HRH-strengthening program uses a twinning model, monitoring of the twinning process and interactions and adapting recruitment and onboarding accordingly could

improve implementation and achievement of results. Mapping and tracking trainee placements and roles following the program would facilitate analysis of the program’s effects on patient outcomes. If there is an expectation that a program should demonstrate a contribution to both systemwide and disease-specific effects, each of these areas of monitoring, evaluation, and learning needs to be designed from the outset to document and assess that dual intent.

CONCLUSION

The HRH Program, funded by PEPFAR from 2012 to 2017, represented an opportunity for a vertical, HIV-focused external donor to invest in horizontal systems change by strengthening Rwandan health professional education institutions to produce a workforce of sufficient quantity and quality to meet the needs of the Rwandan population, including PLHIV. During PEPFAR’s investments in the Program, notable inroads were made in producing more high-quality health workers, and participants in this evaluation were overwhelmingly in support of the Program. The full realization of this opportunity in the form of improved capacity at the institutional level to continually produce health workers was hampered by insufficient planning, muddled communications, and weak monitoring, evaluation, and learning for adaptive management. While important lessons can be drawn from the Program’s successes and its challenges, there was a missed opportunity for systematic learning from the approach taken, due to the lack of a prospective design to document and evaluate the systemwide effects and the specific effects on HIV care.

The future of strengthening HRH in resource-limited settings, in ways that also yield improvements in health care outcomes for PLHIV, requires a reimagining of how partnerships are formed, how investments are made, and how the effects of those investments are documented. The impact of such investments is likely to be greater and more lasting if program investments are longer, multisectoral, and designed with more explicit attention to understanding and meeting health workforce needs in light of the evolving needs of PLHIV.