4

Faculty Twinning

Capacity building in the Human Resources for Health (HRH) Program occurred through a number of activities, including the creation of the Academic Consortium, discussed in Chapter 3, comprising U.S. institutions (USIs) that would conduct mentoring or “twinning”1 with University of Rwanda faculty (CDC, 2012; MOH, 2011b, 2012, 2014, 2016). Although twinning was a key mechanism by which the HRH Program intended to

___________________

1 The World Health Organization defines twinning as a formal, two-way exchange and collaboration between two organizations (WHO, 2001).

build Rwandan health professional educators’ capacity, the 2011 Program proposal makes only two mentions of the practice, one in reference to building leadership teaching capacity, with specific reference to obstetrics and gynecology, and the other in relation to research capacity, whereby a Rwandan principal investigator would be twinned with a foreign co-principal investigator (MOH, 2011a).

In practice, the HRH Program launched and supported 22 training programs across health cadres and specialties, through 16 to 25 participating USIs that collectively deployed about 100 faculty members each year to twin with University of Rwanda faculty members (see Figure 3-6 for a time line showing participating USIs). Twinning under the HRH Program was individual, focusing on one-to-one faculty relationships, with the aim of the USI faculty building University of Rwanda capacity in teaching and clinical care. Although some USIs, such as Harvard Medical School, had longstanding partnerships in Rwanda, most were selected for their specialties and their commitment to recruiting high-quality professionals to stay in Rwanda for extended periods.

Many USI “faculty” members were independent contractors, hired for this specific, time-limited twinning assignment, and many had not worked at the USI previously. Most of these contractors were based in the United States; others were based regionally, such as in Botswana and Kenya. These characteristics of USI faculty twins would prove important for the mixed outcomes of the twinning process, as confirmed in the literature (Cancedda et al., 2018; MOH, 2016; Ndenga et al., 2016) and in qualitative data collected throughout this evaluation. Overall, although most respondents agreed that the first few years of twinning activities faced challenges, by 2019, USI and University of Rwanda faculty and HRH students all reported a mix of successes and challenges.

Twinning was designed as a departure from historically short-term visits (Binagwaho et al., 2013; MOH, 2011a) and was intended not only to promote teaching skills (as well as skills within clinical specialties) to Rwandans, but also to foster mutually beneficial academic partnerships beyond the 7-year HRH Program (Cancedda et al., 2017, 2018; Ndenga et al., 2016). As one respondent noted:

Additionally, HRH helped people to open eyes about partnerships. There were people who have had professional exchanges—those are connections. So, [the] HRH [Program] helped Rwandans to open eyes and to make connection in other countries, especially in the United States. So, that was not a bad thing. (Former HRH Student in Surgery)

Faculty spanning a variety of health-related disciplines (such as medicine, dentistry, nursing and midwifery, and health management) began

arriving and teaching in late 2012 from Academic Consortium institutions (see Chapter 3 for details on the Consortium) to support the 22 training programs (Cancedda et al., 2018). However, not all programs were launched in the same year, reflecting implementation issues with procurement and shifting Ministry of Health (MOH) funding priorities. The initial range of programs included rapid skills upgrading for cadres such as nurses and midwives, targeted boosting of the production of health professionals, and the establishment of specialties and disciplines such as dental surgery and health management.

The midterm review confirmed, as did respondents discussing program management in this evaluation, that the

goals of the twinning—to improve the teaching and clinical specialty skills of Rwandan faculty—were well understood at a senior management level from the beginning … [but] this vision was not trickled down to the faculty and administrative units (e.g., schools, departments) who were meant to drive the model. (MOH, 2016)

This illuminates an important finding: The HRH Program’s twinning approach had a strong vision but lacked operational cohesion in efforts to realize that vision. This was particularly due to two challenges, first in clearly defining the USI faculty contractors’ scopes of work, and then in communicating the scope of the relationship to the University of Rwanda.

USI faculty filled multiple roles during the twinning program, as the midterm review also notes; there was an expectation that USI faculty would have dual roles as sole faculty members in new specialties and as mentors to the first cohort of trainees (MOH, 2016). From the perspective of HRH Program trainees, this expectation came to fruition. They reported that their main mentors and teachers were USI faculty, and the trainees expressed strong appreciation for the education they had received from these individuals. Indeed, throughout data collection, when interviewees referred to “HRH faculty,” they were consistently referring to USI faculty, rather than Rwandan faculty from the University of Rwanda:

So, I actually started to know much about HRH when I was rotating in [obstetrics and gynecology]. So, that’s where I met some doctors from [the] U.S. They were so eager to teach us. Since that time then, up to when I—even now, we’re still communicating (84, HRH Program Trainee, Pediatrics)

HRH trainees reported the USI faculty members’ biggest contribution was in their direct training and professional support of University of Rwanda students, followed by providing clinical services, and, less consis-

tently, in building the capacity of University of Rwanda faculty to teach in these new specialties. Chapters 5 and 6 discuss in more detail the benefits of the USI faculty’s teaching and mentorship on specific outcomes for HRH trainees and the University of Rwanda more broadly.

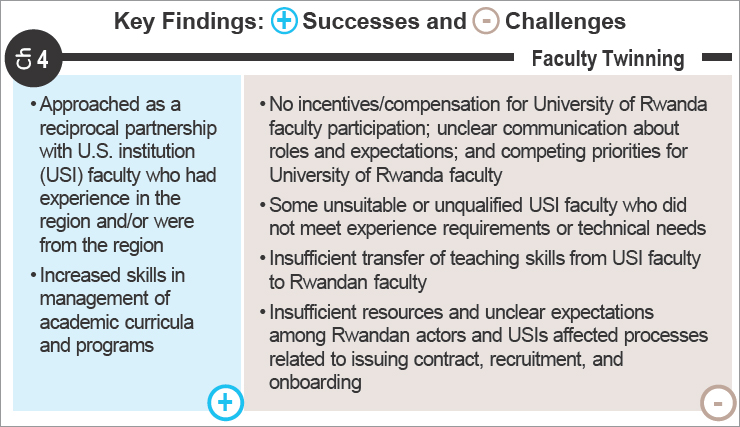

SUCCESSES OF TWINNING

University of Rwanda respondents, USI faculty, and HRH trainees all reported important positive outcomes resulting from twinning relationships, including the approach to twinning as a partnership, rather than a mentor–protégé relationship. The longer duration of USI faculty engagement (1-year contracts versus a more typical 3-month rotation) was noted as a key success factor; one USI faculty member (16) reported that the longer stay showed “a sense of commitment to a department” that helped foster more productive relationships. There is some evidence that being twinned in programs with established University of Rwanda faculty (nursing, pediatrics, and internal medicine) generated more effective twinning relationships than newer programs with fewer Rwandan faculty, such as the Master of Hospital and Healthcare Administration (MHA) program.

Respondents also noted positive twinning outcomes related to increased skills in the management of academic curricula, and the value of having committed USI faculty not only from U.S.-based institutions, but also from the Eastern and Southern African regions, as well as others with experience working in the region.2 This latter factor supported twinning relationships grounded in the cultural humility necessary to form strong relationships between twinned faculty members. Notably, USI faculty who were already in Rwanda and had established relationships there before the start of the HRH Program reported easier transitions into their partnerships with University of Rwanda faculty.

Program Management Skills

University of Rwanda staff most often mentioned transferring program management skills between individually twinned USI faculty and University of Rwanda faculty, resulting in improvements in University of Rwanda faculties’ skills related to their departments’ and residency programs’ organizational structures and processes. They cited specific improvements in planning classes and replacing instructors on leave, scheduling residencies, and organizing internal department structures and external events and con-

___________________

2 For example, some USIs were able to hire staff from outside of the United States to be twins, whereas other universities had restrictions on hiring only individuals from their home states.

ferences, in addition to the in-person support they received in supervising postgraduates:

[In terms of] skills transfer with the twinning model … for instance, the School of Nursing … organized a first group [to attend] the national conference with the HRH Program. Before that, we didn’t have that experience. It is not going to be lost … the skills in terms of planning, working together, and training courses—so there are so many things that I can count that are going to be sustained even after the Program. (81, University of Rwanda Faculty in Nursing)

[F]or some of them [the programs supported through the HRH Program], faculty were well positioned in Rwanda now to think about a new idea or an existing course and have better pedagogical skills…. You know, better skills to think through, like have you develop[ed] a syllabus for a new topic or have you taken a course that seems stale and revamp[ed] it. I definitely think there are more faculty here that can do that in certain programs…. I don’t think there is more physical infrastructure, but I think the teaching infrastructure is better. (64, USI Faculty in Public Health)

Some respondents highlighted the importance of helping with rotation plans. One discussed a sustained rotation plan and evaluation plan for the pediatrics program:

[T]hey did [a] table of rotation, which would be helping even in further years…. And it’s become easier when you have to plan the rotation of residents to follow that the exams before, and it was also helpful to see how they organize the evaluation tools…. Before, people were really evaluated subjectively, which is not professional. And they tried to make it more objective … they also helped us making some modules…. And to categorize a plan to teaching, depending on the field. In pediatrics, it is like general medicine on children then you have to know what way and about cardiology…. So, they [are] trying to specify which field was the required [one] to learn before becoming a pediatrician. It was very good. (85, University of Rwanda Former Student in Pediatrics)

Successes from Sustained Twinning Relationships

Many University of Rwanda and USI faculty discussed the sustained relationships the twinning process created, such as ongoing mentorship, increased University of Rwanda faculty publications, support in curriculum

development, and increased partnerships between the University of Rwanda and USIs (see Chapters 5 and 6 for details).

[There are many] things that we have achieved, including that twinning period or using the twinning model. One of the things that have been a success was the writing. As I am talking with my twin, especially we wrote book chapters together on simulation. That is successful. That was great for me. (80, University of Rwanda Faculty in Nursing)

USI faculty reported that their twinning experiences contributed to University of Rwanda faculty members’ professional development in a variety of ways, most evident in the University of Rwanda twins who subsequently led new departments established by the HRH Program. For example, USI faculty in surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and nursing all reported that their Rwandan twins had taken over the departments. Some USI faculty also highlighted unexpected effects, including their twins taking curricula regionwide and establishing sustained partnerships with USIs:

He’s introduced broad technical skills in [redacted] curriculum, which has then expanded, and [he’s] now going Africa-wide with it. So, a lot of really cool things came out, not just for Rwanda’s [redacted] education but for quality improvement … for the continent, thanks to that partnership. (83, USI Faculty)

Finally, I think, beyond just training in medical, there have been long-lasting friendships and exchange[s] … between Rwanda and different universities in the United States. This went beyond the program itself…. [As] one example, there is one [USI] faculty, who came and … when he returned, … he supervised two, now he has three Ph.D. students, who are completing statistics and epidemiology research in HIV, hepatitis, and drug resistance … and this was not originally planned for HRH, for him to do this kind of training. He was sharing his time in the School of Public Health teachings, research and also working with statistics in RBC [Rwandan Biomedical Center]…. This is what I call beyond Ph.D. scope, no, beyond HRH scope. There have been other benefits, other continuation of linking or bridging Rwanda to the world and universities in the United States. (01, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

USI faculty also reported some unexpected and lasting outcomes for USIs that participated in the HRH Program. This included USI staff whose

contracts had not been renewed; when they moved to work in other countries, many took the experiences and curricula they had gained through the HRH Program with them (16, USI Twinned Faculty in Obstetrics and Gynecology). USI faculty also talked about applying lessons from the HRH Program twinning experience in other countries’ twinning programs.

CHALLENGES WITH TWINNING

Challenges with the twinning program identified during the midterm review were consistent with this evaluation’s data collection across USI faculty, University of Rwanda staff, program administrators, and other stakeholders. Challenges were attributed to a combination of factors and reported consistently across groups. Many respondents noted that although many of the challenges were magnified during the first few years of the HRH Program, there was some improvement as it continued.

Gaps in Incentives and Clarity of Communication

A main challenge reported was the lack of incentives and clear communication to University of Rwanda staff on the purpose and benefits of the HRH Program, which resulted in lack of participation by many in twinning. Many HRH trainees and USI faculty reported that University of Rwanda faculty did not have the time to commit to the twinning process, as many were already fully booked in their existing work, including the concurrent rollout of online curricula. The midterm review similarly revealed a “limited availability of Rwandan faculty to participate in twinning, due to competing clinical, administrative, and teaching responsibilities, as well as sheer faculty shortages” (MOH, 2016).

HRH trainees and USI faculty reported other reasons why Rwandan faculty did not want to participate, most frequently citing poor communication between the MOH and the Ministry of Education (MOE)—and then, between the MOE and its faculty—on the purpose, design, and added value of the HRH Program for University of Rwanda staff. Many University of Rwanda staff reported being surprised when the HRH Program was rolled out. As described in Chapter 3, the MOE was not actively engaged in the design of the HRH Program; the consequence of this was poor communication during early implementation, although communication improved as the Program went on, as discussed below.

In addition, there were no incentives for University of Rwanda faculty to participate; they received no additional compensation for participating in the Program, a fact that was amplified in USI faculty members’ much higher salaries. Moreover, University of Rwanda faculty had many other responsibilities and commitments, and were called on by the MOH to per-

form other functions outside of the educational setting. Respondents noted that University of Rwanda faculty had no agency in choosing whether they would be twinned, or with whom, as part of the HRH Program:

Before they overcommitted … they already had responsibil[ities] and you are not paid by the university to teach. So, now … I decide to make you a teacher without asking you, because I employ you,… there had to be the discussions—you know, we are trying to help the system, we are doing our best, you know we have limited resources and we have this opportunity we are going to manage it this way. I don’t think, anyone took even one minute to invite people—maybe over dinner and say: I am about to overcommit you, I know it may require 2 extra hours of your time and take 2 hours maybe away from your family, but this is what we got do to make our system strong. That never happened. (29, University of Rwanda Former Student in Internal Medicine)

Mismatches in Expectations for Twinning Assignments

There was also a mismatch of expectations and skills between USI and University of Rwanda faculty. The Government of Rwanda reported that many USIs did not provide qualified faculty, mostly (although not exclusively) referring to medical faculty, at the beginning of the Program:

Over time, as we went on mentioning this challenge, the profiles changed and I think they would even send better people. (48, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

USI and University of Rwanda faculty concurred, noting that the initial issue was that USIs were sending physician specialists who did not meet the experience requirements in terms of geographic experience or career stage (e.g., sending early-career USI faculty members to pair with senior University of Rwanda faculty), or who did not match the needed technical area or specialty. As one University of Rwanda faculty member reported, “the mentorship I was expect[ing], I didn’t have it as I expected” (80, University of Rwanda Twinned Faculty in Nursing). Other mismatched expectations related to scopes of work, divisions of labor, and cultural humility:

U.S. faculty, Americans, need to have a huge dose of humility in terms of nothing works there the way it does here. So, if you have an American doctor who orders oxygen [and] it doesn’t come, if it isn’t on the floor, it isn’t good or productive for the American to

get angry and frustrated and take it out on the Rwandan staff who [took] the order. You have to figure out how to deal with those situations. (24, USI Faculty in Internal Medicine)

[S]ome people who came with the HRH program were not deans, by [and] large. Very few people have been deans of school and that’s just the nature of the system in [the] U.S. For example, my dean was twinned with an [American] who had been I think CPD [continuous professional development] in a hospital. Now, … you can say there [were] some general features, in terms of leadership and management. The kind of leadership in mentoring or twinning that would be required for a dean of nursing in an African University that is growing very fast. (02, University of Rwanda Administrator)

USI–University of Rwanda–MOH Relationships and Coordination

USI–University of Rwanda Relationships and Recruitment

Successes in recruiting University of Rwanda faculty varied by specialty. Some new programs, such as the MHA, struggled to recruit sufficient Rwandan faculty to twin with USI faculty. There is some evidence that twinning worked better in more established departments, such as the Master of Science in Nursing (MSN), which had more staff to twin with USI faculty. For specialty programs with challenges in twinning, this resulted in select instances where USI faculty ended up without a twin once they arrived in Rwanda, and instead spent their contracts teaching and providing clinical services. The following discussion compares the MHA and MSN twinning experiences, with a more comprehensive comparison of the programs in Table 5-1.

Graduates from the first MSN cohort were reportedly filtering back to the University of Rwanda, and MSN graduates were seen as motivated to stay at the university because their advanced degrees had more relevance in academia than in direct patient care. By comparison, it was difficult to engage Rwandan faculty in the delivery of the MHA curriculum:

[T]heir entire careers in public health and asking them to shift to hospital management is a completely different career move. So, a lot of faculty, they just don’t want to do this program. Eventually, we had to move the program from the School of Public Health to the School of Health Sciences. We met the same problem. It’s just the University of Rwanda, they don’t have a lot of resources to hire new faculty … specifically for hospital management. So,

everybody was doing whatever they [had] been doing, plus this program. Time-wise, one it was a problem and two whether they’re interest[ed] … to actually shift into a different career is a different story. (15, USI Faculty in the MHA Program)

In the MHA program, and in others, the result was that USI faculty taught students, rather than training faculty to become better teachers. In the emergency medicine residency program, for example, USI faculty had to primarily train students because there were no existing faculty and the first pool of Rwandan faculty recruits were not ready until year 6 of the HRH Program (MOH, 2016).

In the MSN program overall, there were positive reports regarding the skills of USI faculty, many of whom were regionally based, and reports of good twinning relationships, despite some cultural challenges. It also seems that the Rwandan faculty took on more responsibility as USI staff began to wind down in 2017:

From the first cohort, which is quite different from the second, the U.S. staff were the primary one[s] who were teaching us, but currently, as the number was reduced … now Rwandan staff [are] working, but with the collaboration of available staff from [the] USA. (62, University of Rwanda, Former Student in Nursing)

One respondent reported a very positive working relationship with a USI faculty twin who was engaged in the MHA program during the third cohort. Another faculty member from Ethiopia came to Kigali for the second half of the third cohort, and was reportedly very experienced, “because they had the same MHA program in Ethiopia” (81, University of Rwanda Faculty in the MHA Program). These respondents also reported shared learning between USI and Rwandan faculty.

Also in the MHA program, however, some USI faculty who went to Rwanda for the summer were seen as “worse than our own faculty,” in that they did not support students, did not have the answers to students’ questions, and were unable to provide helpful feedback on dissertations (50, University of Rwanda Administrator of Public Health and the MHA Program).

USI–MOH Challenges

USI faculty and administration confirmed many of these challenges in recruitment, administration, and onboarding of USI faculty—a good number of which the midterm review also documents:

- Difficulty finding physician subspecialists available for the 8-week period required by medical curricula (especially for dentistry, radiology, pathology, and ear/nose/throat specialties);

- Delays in funding and contract renewals that delayed or hindered recruiting the necessary physician specialists requested by the MOH, as well as time lines in conflict with U.S. academic calendars;

- Lack of funding for HRH Program advertising and human resources for recruitment;

- Insufficient salaries to attract midcareer, senior, or physician specialist USI faculty, resulting in the recruitment of early- or late-career professionals (MOH, 2016); and

- USIs perceived the cost of losing their own faculty as too high, precluding certain staff from participating as twins (MOH, 2016).

Finally, all respondents reported a lack of regular monitoring of the twinned pairs. Anecdotal reports indicated that the Government of Rwanda initially conducted exit interviews with twins, but the lack of consistent monitoring of these relationships challenged the HRH Program’s ability to learn what was working and what was not, and adapt in real time to improve management and implementation of the twinning process.

CONCLUSIONS

Twinning has been suggested as an effective and collaborative approach to empowering health care professionals in low-resource settings, although it is necessary to gain clarity on the concept before conducting a rigorous impact evaluation. A recent analysis of peer-reviewed publications on twinning projects in global health (Rwanda was not included in the sample) found definitional variation, but identified four attributes of twinning: reciprocity, personal relationship building, a dynamic process, and involvement of two named organizations across cultures. From the concept analysis, the following definition of twinning was generated: “a cross-cultural, reciprocal process where two groups of people work together to achieve joint goals” (Cadée et al., 2016), pointing to a relationship at an institutional level. Twinning programs can also be used to strengthen professional medical associations in low- and middle-income settings (Azimova et al., 2016).

There are several examples of long-term institutional twinning that build teaching and research capacity. The partnership between Makerere University in Uganda and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, which emphasized strengthening research capacity, has graduated 40 doctoral students from Uganda since 2003, and more than 300 faculty and students have

been a part of the exchange (Karolinska Institutet, 2018). Although that program’s focus was on a joint Ph.D. program, students spent a majority of their time in Uganda to ensure research remained focused on local issues, with the remainder spent in Sweden, where they enrolled in specialty courses (Sewankambo et al., 2015).

The institutional partnership between Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences in Tanzania and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), Institute for Global Health Sciences focused on incorporating innovative teaching in curriculum, finding short-term solutions to faculty shortage, and increasing clinical exposure of medical students (Tache et al., 2008). These activities grew to shift from “medical education” to “health professions education” and emphasized interprofessional teamwork. The partnership also benefited UCSF and focused on the institutions’ shared challenges despite differing resources, such as large class sizes and more engagement with a wider range of stakeholders (Pallangyo et al., 2012).

In contrast, the HRH Program twinned USI faculty and University of Rwanda faculty at an individual level, and experienced mixed results in twinning, mostly owing to varied experiences in design, management, and implementation across specialties. Strengths of the model include bringing external faculty and other experts via the memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with USIs, and gains in University of Rwanda staff members’ capacity to manage and plan for new specialty programs and the increased number of students and residents who were flowing through the university and teaching hospitals. However, there was variation across programs, with Rwandan faculty in the MSN program, for example, demonstrating notably increased capacity. The reciprocal nature of twinning relationships was evident in some pairings of USI and Rwandan faculty, though not all, and was found to be more successful where interpersonal relationships had developed between twins. The formation of continued partnerships resulted in new publications and advancement in University of Rwanda faculty’s professional development. However, respondents reported a perceived lack of equality, which is key to reciprocal relationships, between USI faculty and Rwandan faculty’s compensation (Cadée et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, twinning did not meet its original objective of widespread teaching and clinical skills transfer between USI faculty and University of Rwanda faculty, in part because the original design lacked clarity on how to operationalize this unique model, which worked across 25 USIs and 22 programs. On both sides of the relationship (U.S. and Rwandan), lack of resources and time committed to setting up and then managing the initiative created challenges in issuing contracts, recruitment, and onboarding, affecting the overall success of the model. Furthermore, the lack of incentives to encourage University of Rwanda faculty to participate, given their other responsibilities—combined with challenges due to cultural differences

between the USI and University of Rwanda twins—impaired the model’s sustained success. The result was the absence of a dynamic twinning process that allowed for tactical adjustments to improve implementation and likelihood of success.

It is unclear whether learning generated from an Ethiopian twinning program supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief to bolster emergency medicine training was incorporated into the design and management of the HRH Program. In the first year of the Ethiopia project, courses were delivered by U.S. and South African instructors; during year 2, courses were co-taught by foreign and Ethiopian educators, during which time curricula were adapted to the local context; by the third year, capacity had been built in sufficient numbers of Ethiopian instructors to independently deliver the nine emergency medicine modules (Busse et al., 2013). Other twinning and partnership experiences could have offered insights into effective and productive collaborations, including identifying models outside of twinning that could have enabled Rwandan faculty to access USI faculty who were more advanced in their careers but could not physically be in Rwanda for extended periods.

Additionally, the HRH Program did not seem to take into account what is needed or how to teach health professionals to be health professional educators. Evidence indicates that courses designed specifically to build teaching skills can improve teaching confidence, effectiveness, and student outcomes (Brown and Wall, 2003; Godfrey et al., 2004; McLeod et al., 2008).

During implementation, other challenges arose from lack of clear communication from the MOH (and the MOE) to University of Rwanda staff (which did improve over time), and between the MOH and USIs. This resulted in mismatched expectations and poor communication, cultural differences, and lack of coordination across specialties. A midwifery twinning project between the Netherlands and Sierra Leone identified 10 key steps to a twinning program, including evaluating organizational capacity; matching twins based on key criteria; creating avenues and opportunities for twins to communicate, bond, and “create joint stories” and joint projects; and celebrating achievements and successes to encourage ongoing twin relationships (Cadée et al., 2013). Regular interinstitutional communication is also critical to share progress, discuss challenges, and hold partners accountable (Busse et al., 2013). The HRH Program did not appear to incorporate these types of considerations into the planning and implementation process. The short duration of USI faculty stays in Rwanda was seen as another barrier to effective transfer of teaching and clinical skills, reinforcing the evidence that suggests long-term peer-to-peer support is necessary for effective twinning (Kelly et al., 2015).

Where there were successes in management and implementation, these were driven more by individual commitments than longer-term institu-

tional partnerships, especially among USI faculty who had already been in Rwanda or had a particular passion for making this program a success. They often took time out of their own schedules to manage overhead and internal communication issues. On the University of Rwanda side, individual faculty members who had the time, background, and interest in a given specialty also committed to making it a success. Institutionally, despite the recognition that longer-term engagements strengthened twinning relationships, two related factors made longer-term commitments challenging: (1) MOUs were signed for only 1 year at a time; and (2) many USI faculty were contractors, not tied to a specific institution but only hired for that 1-year contract (see Chapter 3 for more detail on the contracting process).

Many of the other successes of the HRH Program are attributed to the overall health professional institutional capacity, findings that are detailed in Chapter 5, and the increased production and capacity of HRH trainees, findings that are detailed in Chapters 6 and 7.

REFERENCES

Azimova, A., A. Abdraimova, G. Orozalieva, E. Muratlieva, O. Heller, L. Loutan, and D. Beran. 2016. Professional medical associations in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Global Health 4(9):e606–e607.

Binagwaho, A., P. Kyamanywa, P. E. Farmer, T. Nuthulaganti, B. Umubyeyi, J. P. Nyemazi, S. D. Mugeni, A. Asiimwe, U. Ndagijimana, H. Lamphere McPherson, D. Ngirabega Jde, A. Sliney, A. Uwayezu, V. Rusanganwa, C. M. Wagner, C. T. Nutt, M. EldonEdington, C. Cancedda, I. C. Magaziner, and E. Goosby. 2013. The Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda—new partnership. New England Journal of Medicine 369(21):2054–2059.

Brown, N., and D. Wall. 2003. Teaching the consultant teachers in psychiatry: Experience in Birmingham. Medical Teacher 25(3):325–327.

Busse, H., A. Azazh, S. Teklu, J. P. Tupesis, A. Woldetsadik, R. J. Wubben, and G. Tefera. 2013. Creating change through collaboration: A twinning partnership to strengthen emergency medicine at Addis Ababa University/Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital—a model for international medical education partnerships. Academy of Emergency Medicine 20(12):1310–1318.

Cadée, F., H. Perdok, B. Sam, M. de Geus, and L. Kweekel. 2013. “Twin2twin” an innovative method of empowering midwives to strengthen their professional midwifery organisations. Midwifery 29(10):1145–1150.

Cadée, F., M. J. Nieuwenhuijze, A. L. Lagro-Janssen, and R. De Vries. 2016. The state of the art of twinning, a concept analysis of twinning in healthcare. Global Health 12(1):66.

Cadée, F., M. J. Nieuwenhuijze, A. L. M. Lagro-Janssen, and R. de Vries. 2018. From equity to power: Critical success factors for twinning between midwives, a Delphi study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 74(7):1573–1582.

Cancedda, C., R. Riviello, K. Wilson, K. W. Scott, M. Tuteja, J. R. Barrow, B. Hedt-Gauthier, G. Bukhman, J. Scott, D. Milner, G. Raviola, B. Weissman, S. Smith, T. Nuthulaganti, C. D. McClain, B. E. Bierer, P. E. Farmer, A. E. Becker, A. Binagwaho, J. Rhatigan, and D. E. Golan. 2017. Building workforce capacity abroad while strengthening global health programs at home: Participation of seven Harvard-affiliated institutions in a health professional training initiative in Rwanda. Academic Medicine 92(5):649–658.

Cancedda, C., P. Cotton, J. Shema, S. Rulisa, R. Riviello, L. V. Adams, P. E. Farmer, J. N. Kagwiza, P. Kyamanywa, D. Mukamana, C. Mumena, D. K. Tumusiime, L. Mukashyaka, E. Ndenga, T. Twagirumugabe, K. B. Mukara, V. Dusabejambo, T. D. Walker, E. Nkusi, L. Bazzett-Matabele, A. Butera, B. Rugwizangoga, J. C. Kabayiza, S. Kanyandekwe, L. Kalisa, F. Ntirenganya, J. Dixson, T. Rogo, N. McCall, M. Corden, R. Wong, M. Mukeshimana, A. Gatarayiha, E. K. Ntagungira, A. Yaman, J. Musabeyezu, A. Sliney, T. Nuthulaganti, M. Kernan, P. Okwi, J. Rhatigan, J. Barrow, K. Wilson, A. C. Levine, R. Reece, M. Koster, R. T. Moresky, J. E. O’Flaherty, P. E. Palumbo, R. Ginwalla, C. A. Binanay, N. Thielman, M. Relf, R. Wright, M. Hill, D. Chyun, R. T. Klar, L. L. McCreary, T. L. Hughes, M. Moen, V. Meeks, B. Barrows, M. E. Durieux, C. D. McClain, A. Bunts, F. J. Calland, B. Hedt-Gauthier, D. Milner, G. Raviola, S. E. Smith, M. Tuteja, U. Magriples, A. Rastegar, L. Arnold, I. Magaziner, and A. Binagwaho. 2018. Health professional training and capacity strengthening through international academic partnerships: The first five years of the Human Resources for Health Program in Rwanda. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7(11):1024–1039.

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2012. Request approval to award a multi-year expansion supplement exceeding 25% for the cooperative agreement PS099118, 3U2GPS2091 “Strengthening the Ministry of Health’s Capacity to Respond to the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the Republic of Rwanda under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)” and approval to waive the requirement of an objective review for the single awardee to this cooperative agreement. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 7. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

Godfrey, J., R. Dennick, and C. Welsh. 2004. Training the trainers: Do teaching courses develop teaching skills? Medical Education 38(8):844–847.

Karolinska Institutet. 2018. Makerere University and KI strengthen partnership. https://news.ki.se/makerere-university-and-ki-strengthen-partnership (accessed November 4, 2019).

Kelly, E., V. Doyle, D. Weakliam, and Y. Schönemann. 2015. A rapid evidence review on the effectiveness of institutional health partnerships. Global Health 11(1):48.

McLeod, P. J., J. Brawer, Y. Steinert, C. Chalk, and A. McLeod. 2008. A pilot study designed to acquaint medical educators with basic pedagogic principles. Medical Teacher 30(1):92–93.

MOH (Ministry of Health). 2011a. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program, 2011–2019: Funding proposal. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2011b. U.S. academic institutions—selection rationale. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

MOH. 2012. HRH application brief cabinet paper, May 2012–30 Sept 2013. Kigali, Rwanda: MOH. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

MOH. 2014. Human Resources for Health monitoring & evaluation plan, March 2014. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

MOH. 2016. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program midterm review report (2012–2016). Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health. (Available by request from the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

Ndenga, E., G. Uwizeye, D. R. Thomson, E. Uwitonze, J. Mubiligi, B. L. Hedt-Gauthier, M. Wilkes, and A. Binagwaho. 2016. Assessing the twinning model in the Rwandan Human Resources for Health Program: Goal setting, satisfaction and perceived skill transfer. Global Health 12:4.

Pallangyo, K., H. T. Debas, E. Lyamuya, H. Loeser, C. A. Mkony, P. S. O’Sullivan, E. E. Kaaya, and S. B. Macfarlane. 2012. Partnering on education for health: Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences and the University of California San Francisco. Journal of Public Health Policy 33(Suppl 1):S13–S22.

Sewankambo, N., J. K. Tumwine, G. Tomson, C. Obua, F. Bwanga, P. Waiswa, E. Katabira, H. Akuffo, K. E. Persson, and S. Peterson. 2015. Enabling dynamic partnerships through joint degrees between low- and high-income countries for capacity development in global health research: Experience from the Karolinska Institutet/Makerere University partnership. PLoS Medicine 12(2):e1001784.

Tache, S., E. Kaaya, S. Omer, C. A. Mkony, E. Lyamuya, K. Pallangyo, H. T. Debas, and S. B. Macfarlane. 2008. University partnership to address the shortage of healthcare professionals in Africa. Global Public Health 3(2):137–148.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. Guidelines for city twinning. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization.