OVERALL EFFECT OF THE HUMAN RESOURCES FOR HEALTH PROGRAM

Rwanda made substantial progress to reach the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90-90-90 targets prior to the Human Resources for Health (HRH) Program, which was facilitated by the Government of Rwanda’s commitment to confronting its HIV epidemic. The development of national strategic plans on HIV/AIDS, the decentralization of the Rwandan health system, and the movement toward community-based health insurance and performance-based financing facilitated the country’s achievements and remarkable progress toward expanding access to HIV services and toward achieving HIV epidemic control (MOH, 2009a,b, 2018). Rwanda had also made substantial progress in achieving Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 (improve maternal health), with the maternal mortality ratio decreasing dramatically, from 1,160 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 373 in 2010, and to 275 in 2015 (WHO, 2017). There has been notable progress in all five provinces in Rwanda since 2005 in births attended by a skilled health professional, increasing from 31 percent in 2000 to 69 percent in 2010 (MDG Monitor, 2015). By 2015, 91 percent of deliveries were reportedly assisted by a skilled provider, most often by a nurse or medical student, followed by deliveries attended by a doctor, and then by a midwife (NISR et al., 2016).

In this respect, this context created an opportunity to make a broader impact in Rwanda’s HIV program. The third Health Sector Strategic Plan (2012–2018) called for the integration of HIV services at a decentralized level, the need to improve quality, and the need to maintain trained and adequate numbers of staff at all facilities (MOH, 2012). The result of decentralization has been a rapid increase in the number of facilities offering antiretroviral therapy (ART) services, from 4 facilities in 2002 to 552 in 2016, as reported in the Rwanda Integrated Health Management Information System. The increase in output and distribution of high-quality trained health professionals across Rwanda as a result of the HRH Program was seen by all respondent groups in this evaluation as having a positive impact on the quality of care as an outcome of increased access, although that is not explicitly noted in the overall design of the Program.

THE HIV EPIDEMIC IN RWANDA

With the first National Strategic Plan on HIV/AIDS in 2009, the Government of Rwanda cemented its commitment to tackling HIV by calling for universal access to HIV treatment and establishing goals of reducing infections, morbidity, and mortality, as well as ensuring equal opportunities for people living with HIV (PLHIV) (MOH, 2009b). In addition, the plan stated

that all PLHIV should receive prophylaxis for opportunistic infections. Even before the plan’s release, in 2008 national policy had eased the cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count threshold for ART treatment to less than or equal to 350 cells/mm3 from 200 cells/mm3 (Nsanzimana et al., 2015). Further changes in the CD4 count threshold for ART initiation were made in 2013. By 2014, Rwanda was fully implementing Option B+ in which HIV-positive pregnant women are enrolled on lifelong ART regardless of CD4 count. This expansion included anyone with tuberculosis co-infection, hepatitis B or C, and all children under 5 years old (MOH, 2013; Ross et al., 2019). On July 1, 2016, the Government of Rwanda rolled out the Treat All plan that required treatment of all HIV-positive patients regardless of CD4 count, age, comorbidities, or clinical staging (Nsanzimana et al., 2017; Ross et al., 2019).

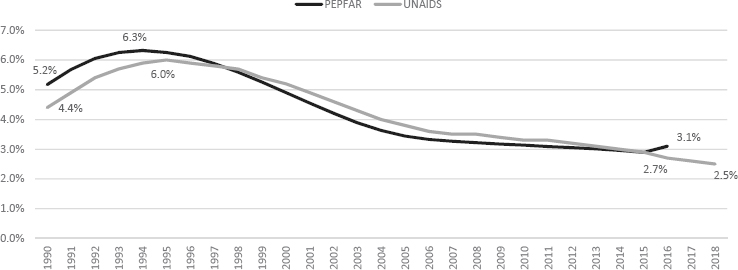

As Figure 7-1 shows, HIV prevalence among adults age 15–49 in Rwanda, as reported by both the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and UNAIDS, has been steadily decreasing since its peak at around 6 percent between 1994 and 1995, when sexual violence was used as a mechanism of terror and a means to spread HIV following the genocide against the Tutsi (Donovan, 2002; Nsanzimana et al., 2015).

The 2019 Rwanda Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment (RPHIA) estimated HIV prevalence among adults aged 15–49 as 2.6 percent and 3 percent among adults aged 15–64 years, totaling approximately 210,200 adults in Rwanda living with HIV (RPHIA, 2019). These are in line with the UNAIDS 2018 estimates of 2.5 percent of adults aged 15–49 living with HIV, totaling 210,000 people (UNAIDS, 2018b).

As discussed below, the RPHIA estimated that the annual incidence of HIV among adults was approximately 5,400 new cases per year, higher than the UNAIDS estimate of 3,600 total new infections per year and PEPFAR’s estimate of 4,409, although the confidence intervals for both

SOURCES: PEPFAR, 2018; UNAIDS, 2018a,b.

estimates overlap. The variation between the RPHIA and UNAIDS estimates likely point to methodological differences (PEPFAR Rwanda, 2019; RPHIA, 2019; UNAIDS, 2018b).

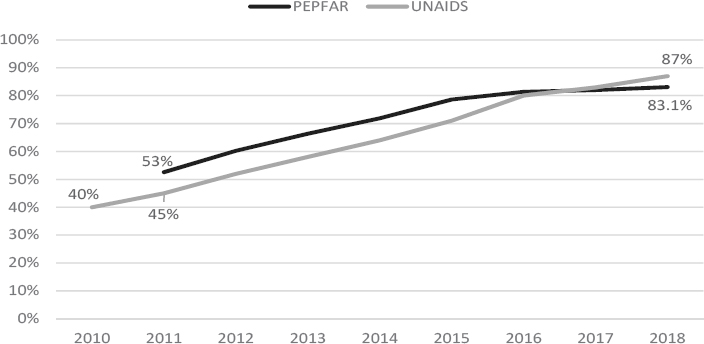

In the past decade, Rwanda has made steady improvements in increasing access to and coverage of ART (see Figure 7-2), although there is some discrepancy in the data. PEPFAR and UNAIDS reported ART coverage as 66 percent and 58 percent, respectively, in 2013, while elsewhere it was reportedly 92 percent in the same year (Binagwaho et al., 2016). Additionally, both PEPFAR and UNAIDS data present an approximately 8 percent differential, likely due to methodological differences. PEPFAR collects programmatic data from select core indicators, whereas UNAIDS compiles estimated HIV data produced by host countries. The Ministry of Health (MOH) 2016 Annual Statistics Booklet indicated ART coverage was 83 percent in 2016 (MOH, 2016a). In 2014, mortality was estimated to be greatest among those who were untested (35.4 percent) and those on ART (34.1 percent)—reflective of the increased and aging population on ART—followed by patients lost to follow up (11.8 percent) (Bendavid et al., 2016). More information about care and treatment services for PLHIV is covered in the subsequent sections about the health system and human resources for health in Rwanda.

HIV/AIDS Outcomes

The RPHIA and UNAIDS both estimate that approximately 74 percent of PLHIV have achieved viral suppression (RPHIA, 2019; UNAIDS, 2018b); however, estimates of the three 90-90-90 elements are different (see Table 7-1). Results from the RPHIA show that 76 percent of HIV-positive

SOURCES: PEPFAR, 2018; UNAIDS, 2018a,b.

TABLE 7-1 Progress Toward 90-90-90 Treatment Cascade Targets in Rwanda

| Indicator | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of PLHIV who know their status | 88% | 90% | 92% | 94% | 83.8% |

| Percentage of people who know their status who are on ART | 81% | 88% | 90% | 93% | 97.5% |

| Percentage of people on ART who achieve viral suppression | — | 82% | 83% | 85% | 90.1% |

| Percentage of all PLHIV who achieve viral load suppression | — | 65% | 69% | 74% | 76% |

NOTES: ART = antiretroviral therapy; PLHIV = people living with HIV. Data for 2019 are taken from the RPHIA for adults aged 15–64 years.

SOURCES: RPHIA, 2019; UNAIDS, 2018b.

adults (aged 15–64) and almost 80 percent of HIV-positive women have achieved viral load suppression, a key indicator of effective HIV treatment in a population (RPHIA, 2019). Overall, the RPHIA found that approximately 84 percent of adults living with HIV knew their status, 98 percent of adults who knew their status were on ART, and 90 percent of those on ART achieved viral suppression.

Impact on Quality of Care

Dimensions of Quality

The landmark 2001 Crossing the Quality Chasm report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) presents six dimensions of high-quality health care (IOM, 2001), which were adapted in 2018 for application in global health (NASEM, 2018):

- Safety: avoiding harm to patients from the care that is intended to help them.

- Effectiveness: providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (that is, avoiding both overuse of inappropriate care and underuse of effective care).

- Person-centeredness: providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that people’s values guide all clinical decisions. Care transitions and coordination should not be centered on health care providers, but on recipients.

- Accessibility, timeliness, and affordability: reducing unwanted waits and harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care; reducing access barriers and financial risk for patients, families, and communities; and promoting care that is affordable for the system.

- Efficiency: avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy, and including waste resulting from poor management, fraud, corruption, and abusive practices; existing resources should be leveraged to the greatest degree possible to finance services.

- Equity: providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, race, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

Impact on HIV/AIDS Care

The design of the HRH Program emphasized developing a quality health care system through an increased output and cadre of high-quality trained health professionals who would in turn increase the quality of care. As mentioned above, the increase in output and distribution across Rwanda was seen to have had a positive impact on the quality of care as an outcome of increased access, although that is not explicitly noted in the overall design of the program. HRH Program trainees gained skills and knowledge that were seen as having a positive effect on the quality of care for all Rwandans, including PLHIV. With highly trained health workers distributed across Rwanda, the management of patients with HIV was seen to be improving. Most notably, the HRH Program was credited with bringing specialties that PLHIV required for comprehensive care, including treatment for people with advanced HIV disease or in need of specialized care:

[I]n 2012, … we were at a certain stage in the way we treat HIV; we [had] started giving antiretrovirals around 2005 or 2006 … American[s] had bigger experience because they started giving antiretrovirals in 1998, 1999, 2000. So, they were ahead of us in terms of … [how to manage the] complications of medication, the side effects…. So we benefitted directly from their [U.S. institution faculty’s] presence…. HRH [also] brought specialists … which helped people to grasp … some of the areas they were not familiar with, most importantly the teaching…. [T]hey helped us to know what exactly is normal and what HIV does on systems and in that way we were capable of better understanding and better treating our patients. (35, University of Rwanda Faculty in Internal Medicine and Professional Association Representative)

A respondent from a PLHIV group noted that specialized care was particularly relevant for HIV-positive pregnant women, as “residents’ level has improved as they have been well taught to minimize [the] risks” of mother-to-child transmission (30, Former Government of Rwanda Program Administrator and PLHIV Representative). Exposure to U.S. institution (USI) faculty was also seen as contributing to reduced stigma and improved treatment of HIV-positive women presenting with cervical cancer:

Patients with HIV are much more likely to get cervical cancer and have much more aggressive forms of cervical cancer. I encountered a lot of HIV patients in our practice and a lot … we worked a lot to try to keep them from getting discriminated against … in treatment choices. (16, USI Faculty in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

Another respondent commented that “as more internal medicine residents go out to districts, I think that will help with the management of more advanced opportunistic infections and some of those things” (12, International NGO Representative). Here, it is important to note that not enough time had lapsed between the graduation of internal medicine doctors under the HRH Program and this evaluation to assess this type of impact. However, it was also observed that some specialties required for providing comprehensive services to PLHIV (notably, nephrology) were absent from the HRH Program. As combination ART has led to substantial improvements in opportunistic-disease associated mortality among PLHIV, comorbid noncommunicable diseases have become increasingly common in HIV management, in part as a natural consequence of longevity, but compounded by dysmetabolism associated with antiretroviral drugs (Koethe, 2017). Thus, HIV care must also focus on prevention and management of these illnesses, and on the complexity that arises in caring for an aging PLHIV population with multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and frailty (Guaraldi and Palella, 2017).

For program administrators, the impact on HIV was observed through the increases in the quality of care and management at health facilities by HRH trainees, reinforcing the integrated HIV service delivery Rwanda had been working toward since 2009. This was facilitated by the existing structures of HIV service delivery, which included doctors and nurses at hospitals who functioned as infectious disease specialists (including for HIV and tuberculosis), and received ongoing training from the MOH outside of the HRH Program.

Because the HRH came in within the framework that already exist[ed] to already deal with HIV/AIDS … it eased the task since the framework was already there, and people had already started

to get awareness on HIV. I think it has been a trampoline for the HRH, because it did not have to start afresh and build a structure. It came into a structure that already existed. (43, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

One program administrator from the MOH drew a direct link between the improvements in HIV-related indicators and the increase in clinicians’ skills and knowledge as a result of the HRH Program:

[If I compare the HIV incidence] report from 2010 … to 2015, it’s a decline of about of 15 percent of new infections, so incidence is reduced by half.… Second is the mortality [related to AIDS] … it was around 50 percent, and today the mortality has declined to around 5 percent. And this is the highest mortality declined around the world…. Third, it is the transmission of HIV from mother to child … reduced from 4 percent [in] 2012 to 1.5 percent today (Actually by 2016 it was 1.8 percent.) … because of several factors…. It is important to show that this outcome, [these] good results, are attributed to HRH, this program…. And this is probably going to be kind of [a limitation], given the methods I have seen applied. But I’m sure the results are coming because people did something. It’s humans who are driving the changes and doctors, nurses are those who are forefront of the management. The pills have improved, it is true, the infrastructure has also improved, but probably the expertise, this and the knowledge has its own important place in the results we are talking about. (01, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

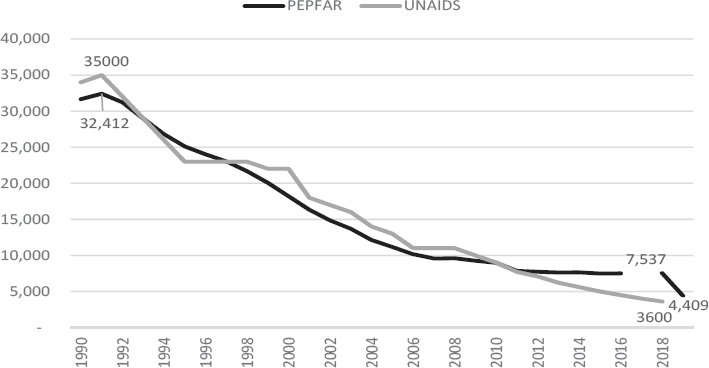

After declining from a high of more than 30,000 per year in the early 1990s, the number of new infections reported by PEPFAR leveled off to approximately 7,500 new infections per year in 2018 (see Figure 7-3). In 2019, this number was reported to be 4,409 in PEPFAR’s Country Operational Plan 2019 using the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package Spectrum estimate (PEPFAR Rwanda, 2019). However, UNAIDS HIV incidence data suggests a gradual decline in the number of new HIV infections, reportedly estimated at 3,600 new infections per year in 2018.

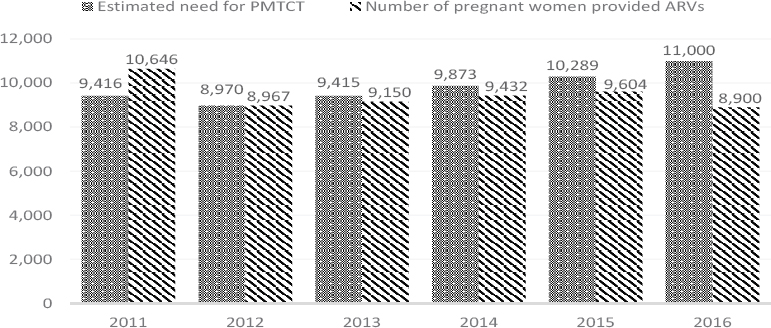

Furthermore, annual incidence reported by the RPHIA in 2019 was 0.08 percent, which corresponds to approximately 5,400 new cases (RPHIA, 2019). Although the incidence rate has continued to decline since 2008 and is reflective of a successful national HIV program, the discrepancies in these data are notable, with implications for assessing the nature of the HIV epidemic in Rwanda even with methodological differences. Other indicators, such as the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) coverage,

SOURCE: PEPFAR, 2018; UNAIDS, 2018a,b.

estimated a decline in coverage from 113.1 percent in 2011 to 80.9 percent in 2016 for PEPFAR (see Table 7-2). UNAIDS estimates of PMTCT coverage have increased significantly, from 58 percent in 2010 to a leveling of around or above 95 percent. The estimated increases in coverage were seen throughout the years of the HRH Program implementation, although its estimations of coverage vary significantly in comparison to PEPFAR, likely pointing to methodological differences. This drop in coverage percentage occurred as the estimated need for PMTCT coverage rose from 9,416 pregnant women in 2011 to 11,000 in 2016, while the number of pregnant women who were provided antiretrovirals (ARVs) dropped from 10,646 to 8,900 (see Figure 7-4).

Impact on Other Clinical Areas

The HRH Program was also seen as having a positive impact on other clinical areas. The Program’s production of obstetricians/gynecologists was viewed as contributing to Rwanda’s 2015 achievement of MDG 5—to

TABLE 7-2 UNAIDS and PEPFAR Estimates of PMTCT Coverage in Rwanda, 2011–2016

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNAIDS | 58% | 91% | 81% | 86% | 93% | > 95% | > 95% | 94% | > 95% |

| PEPFAR | — | 113% | 100% | 97% | 96% | 93% | 81% | — | — |

SOURCES: PEPFAR, 2018; UNAIDS, 2018b.

NOTE: ARV = antiretroviral (drug); PMTCT = prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

SOURCE: PEPFAR, 2018.

reduce the maternal mortality ratio by three quarters between 1990 and 2015—which decreased from 1,160 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 373 in 2010, and to 275 in 2015 (WHO, 2017). More broadly, improvements around hand hygiene and use of personal protective equipment were observed and contributed to improved patient outcomes.

Other aspects of quality care were seen to have improved. Many respondents noted patient flow as having been positively influenced by interactions between USI and Rwandan faculty and students. Improving clinicians’ time management, triage practices, and scheduling rosters, and improved clinical guidelines (although the ever-changing HIV-related clinical guidelines were seen as challenging) were all seen as contributing to reduced patient waiting times and flow through the hospitals (30, Former Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator; 58 and 59, University of Rwanda Former Students in Nursing). This interaction also enhanced Rwandan faculty and student awareness and implementation of evidence-based medicine, which respondents saw as directly related to improved quality of care:

HRH changed the way the doctors look for evidence. Initially, we do routine things because someone told you, “We do this, you do that”; you do not know why and what is the basis to do this and not to do that. HRH were very specific to teach people before doing something, know why you are doing it, what else, how is it done elsewhere, what is the evidence, what to expect. (35, University of Rwanda Faculty in Internal Medicine and Professional Association Representative)

Impact of Other Quality Improvement Activities

Quality improvement activities supported by concurrent projects and initiatives also contributed to improved quality of care. In Bushenge Hospital, for example, which was included in this evaluation’s in-depth facility microsystem examination, a quality improvement project supported by a United States Agency for International Development implementing partner to reduce postsurgical infections was seen as improving care, although there was also an interactive effect with the HRH Program, as specialists produced by the Program and working in Bushenge Hospital “will make it easier for those hospitals to improve” (05, International NGO Representative).

Other activities that affected the health workforce and the provision of care include identifying gaps in service delivery, in-service training on HIV service delivery, continuing professional development and mentorship programs, external provision of ARVs, and results-based financing. A strong program of community-based HIV service delivery by community health workers was seen as having an impact on patient-level outcomes (Abbott et al., 2017). Similarly, the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Butare/University Teaching Hospital, Butare (CHUB), also included in the facility microsystem in-depth examination, received support from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to provide comprehensive pediatric HIV services, which could have had a plausible impact on HIV outcomes.

Although these improvements in quality of care were observed in tertiary care facilities, such as CHUK (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Kigali/University Teaching Hospital, Kigali) or CHUB, for example, it was recognized that most Rwandans did not seek services from these hospitals; rather, they accessed care in health centers and district hospitals, which were not as affected by the HRH Program:

I think the care available at places like CHUK, CHUB today is profoundly better than what it used to be and I think HRH does have a lot of inputs into that. Absolutely. The reality is that the vast majority of people in Rwanda do not seek care from CHUK or CHUB or these teaching institutes…. [T]he vast majority of HIV care is provided at the health centers by nurses. The next level is the district hospitals, and so I think you have to recognize the limitation of what an investment in the tip of the pyramid has on the entire base of the pyramid. (12, International NGO Representative)

Related was the purchase and distribution of equipment for clinical teaching, which predominantly went to CHUK and, to a lesser extent, CHUB (see Chapter 6). This respondent, however, did not take into account

the nurses whose skills were upgraded from A2 to A11 as a result of the e-learning platform developed under the HRH Program, or other efforts and investments made in upgrading nurses’ skills. Although shifting HIV care tasks to nurses had occurred in 2009,

nurses were trained to [provide HIV services], but with not having enough capacity and enough background to address and tackle everything, but through this program, people were getting more knowledge on how to handle HIV conditions on clinical and psychological and economical aspects of the problem. (32, University of Rwanda Non-Twinned Faculty and Former Student in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

Hospital-level leadership was also seen as influencing quality of care. Although management processes were well defined, quality improvement tended not to be institutionalized at the leadership level for ongoing improvement. Additionally, 2017 saw a significant “shake up of the system” in which hospital directors were moved or removed, causing “huge management instability” (12, International NGO Representative). Simultaneously, however, more team-based approaches to decision making were installed, in part due to the HRH Program, which was seen as a forward step.

Other factors also affected health workers’ ability to provide quality of care. At the facility level, the absence of infrastructure and equipment impaired their work. Conditions in rural and remote areas made them undesirable locales to work and live, impeding health worker retention and contributing to a situation in which there were insufficient human resources for health at the facility level, creating a more burdensome workload for health workers who stayed.

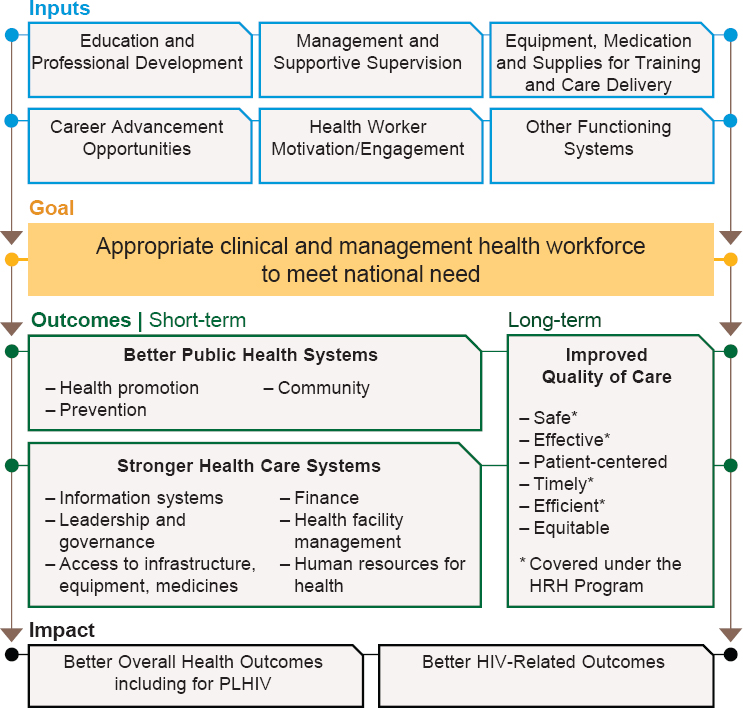

Linking Quality of Care to Patient Outcomes

Data from this evaluation suggest revisions to the theoretical causal pathway that guided the evaluation design, presented in Chapter 1, that more clearly link HRH Program activities and outputs to the domains of quality presented in Figure 7-5. Through building awareness and use of evidence-based medicine and quality improvement methodologies, the safety and effectiveness of clinical interventions were seen as improving. The HRH Program was seen as building a cadre of physician specialists, including in specialties for which there previously were no providers, thereby increasing access; however, the geographic distribution of some specialties was an ongoing barrier.

___________________

1 A2 nurses have completed secondary school education, and A1 nurses receive a diploma after 3 years of training at a higher education institute (Uwizeye et al., 2018).

NOTE: HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HRH = human resources for health; PLHIV = people living with HIV.

Beyond building clinical skills, the Program also was seen to have an effect on time management and patient flow, thereby improving the timeliness of services. Although this view was not widespread, one USI faculty member noted that there had been some improvements in treatment for and reduction in stigmatization of HIV-positive cervical cancer patients, which may point to small inroads in improving equity.

Therefore, the committee revised the causal pathway to highlight the role of improved quality of care as a longer-term outcome that is required to effectively impact health outcomes for all and HIV-related outcomes. Investments in human resources and other health systems strengthening blocks need to evolve over time as the context and needs of the population change; however, ongoing investments are required to continue to improve the health outcomes of Rwandans.

Measuring Impact

The committee did not have sufficient data to provide a quantitative assessment of the HRH Program’s impact on health outcomes. That said, the design of the Program, in principle, would have allowed a quantitative assessment of changes in outcomes following implementation. The clear outset of the Program, its defined set of training activities, and the distribution of HRH trainees across Rwanda mean that a quantitative assessment of impact with reasonable potential for causal attribution could, in principle, be carried out as follows: The design would conceptualize Rwandan districts that received HRH trainees as independent units with their own trajectories of health outcomes such as HIV testing, treatment, and viral suppression rates. The new infusion of HRH trainees would then be tested as an “intervention” that is applied to each district at a unique “dose” that is represented by the quantity and type of HRH trainees who enter each district, ideally characterizing dose in relation to population or disease burden. Designs such as regression discontinuity, interrupted time series, or difference-in-difference could then use district-level fixed effects to estimate the pooled effect of the Program on the outcomes of interest.

The information needed for such an analysis would allow the creation of panel data for districts, with two central pieces of data: (1) repeat observations over time (e.g., monthly or quarterly) of the health outcomes of interest, before and after the implementation of the HRH Program; and (2) detailed information on the trajectory of HRH trainees in districts, including the timing, type of health professional, and any ancillary information about the types and intensity of clinical services provided by the trainee. These two data elements could provide minimal but sufficient foundation for a quantitative assessment of impact. Unfortunately, neither of these key data elements was available to the committee. The committee posits that future HRH efforts could fill key knowledge gaps around the potential for impact on a range of individual and population health outcomes by conceptualizing, a priori, a rigorous evaluation design that fits with the planned HRH intervention. Such evaluations would ideally be designed with input from implementers and stakeholders, but executed by independent teams who are separate from those implementing the program.

SUSTAINABILITY AND INSTITUTIONALIZATION

Continuing the HRH Program

Government of Rwanda program administrators shared that the HRH Program continued, following the end of PEPFAR investments, as there was an ongoing need to generate specialists in medicine and nursing. Referring

to the 2011–2019 period as phase one, one of these respondents declared, “the HRH Program will never end. That is our motto” (03, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator). The HRH Program was seen as being “Rwandan owned, where Rwandans decide what they want to do and decide who they want to hire” (13, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator). The end of PEPFAR funding was seen as causing “a kind of unbalance” in terms of sustainability, but the Program continued with government commitment and resources from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (20, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator).

There was general interest in continuing the HRH Program and making “longer-term investments” to facilitate USI faculty members’ staying for longer periods at the University of Rwanda to continually build capacity and “give the residents a lot more security and faith in the program when they don’t just see people coming and going all the time” (16, USI Faculty in Obstetrics and Gynecology). There was a perceived need to continue building physician specialists and subspecialists and

through this project, establishing a further project on how to train subspecialists will be much easier…. I think we are now self-reliant, but we want to go much deeper so that we have specialists in the country who can manage everything. (32, University of Rwanda Faculty and Former Student in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

University of Rwanda and USI respondents alike expressed confusion about the future of the HRH Program. University of Rwanda respondents were unclear as to whether additional USI faculty would be coming and were concerned about being able to continue their programs without the support:

We have been twinning until June, but we are promised to get other faculty to assist in August, next month, because we are still running the programs, and some of them have been getting the Ph.D. holders, but others are still missing some faculty with Ph.D. that may continue to run programs. We hope that in August we get other faculty to come and join. (67, University of Rwanda Faculty in Nursing and Midwifery and Former Student in Nursing)

USIs had differing understandings, with one respondent reporting he had not heard from the MOH about continuing to support the surgery program and another who had only recently heard from the MOH that her institution would be issued a memorandum of understanding for another year to support the nursing program.

Additional partnerships with other USIs were reportedly being formed directly with the University of Rwanda, which was motivating to Rwandan faculty:

We are connected to the University of Utah in the U.S., which has a Ph.D. program in neonatal and they’re coming soon … 3 faculty and 12 students, they’re coming to join us for 2 weeks [of] training. And because we created those networks, [so] that you can have further qualification in our specialization of neonatology, I feel motivated and my eyes are open to keep moving. (47, University of Rwanda Faculty and Former Student in Nursing)

Sustaining HRH Program Outputs

Investments in the University of Rwanda, both in faculty and in postgraduate training, were key to sustaining the HRH Program’s gains. For Government of Rwanda program administration respondents, the fact that university departments were all headed by Rwandans was an indication that the Program had been institutionalized:

[T]he University of Rwanda itself and all departments, there is no department that is headed by foreigners or visiting faculty. All departments were headed by national faculty. (03, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

That the health workers trained under the HRH Program brought higher skill levels and qualifications to the health sector was viewed as another measure of sustainability. Similarly, the experience of being twinned with USI faculty was viewed as contributing to Rwandan faculty members’ professional development and growth:

If I work with you, you will always be my role model. So, in a way, I will always know I have this and that, and that. That is the sustainability. (46, Professional Association Representative in Nursing and Midwifery)

One respondent external to the HRH Program (12, International NGO Representative) expressed that some of the products of the Program, such as curricula and formal degree programs, could be sustained, but it was unclear whether there would be faculty to continue delivering these programs.

Sustaining the Institutional Capacity to Train Health Workers

As indicated in the design phase, the MOH did not engage the Ministry of Education in the design of the HRH Program; however, throughout implementation, the relationship between the two ministries grew. Building the capacity of new and existing faculty at the University of Rwanda was seen as contributing to the sustainability of the Program:

I think HRH has invested a lot in Ministry of Education. They have invested a lot in a future, or maybe current and future faculty. And that’s sustainable. They always have teachers; they will always have people in the hospitals who are capable to train future health workers. (13, Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

Another Government of Rwanda respondent expressed that having a university capable of producing more health workers was an unplanned benefit of the Program, making it “even more sustainable than what we believe” (18, Former Government of Rwanda HRH Program administrator). An HRH trainee who went on to work as a physician specialist at CHUB and joined the faculty at the university felt that the transition from USI faculty to Rwandan faculty was successful, facilitating the university’s sustained capacity to educate future health workers:

I think this was just well done, because they had made this transition period. It was not an abrupt window, so, the 5 years was just over surveying everything but the last 2 years was just transition period where local faculty has to take everything, and we are just like us taking into the hands and share managing things and giving feedback under how things should be and this has helped local faculty to feel comfortable because there was period of time for them to be like supervisors, to see how they are handling things, so it was a smooth ending to things. (32, University of Rwanda Non-Twinned Faculty and Former Student in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

USI faculty perspectives contrasted with this view. The notion that they trained Rwanda faculty “to become better teachers in a specific area … didn’t work that way” (15, USI Twinned Faculty in the Master of Hospital and Healthcare Administration Program). Another USI faculty member who had four consecutive contracts with the MOH to provide teaching, twinning, and direct services for complex gynecology oncology cases in Kigali noted:

I’ve been here as a constant for 4 years, there’s been a lot of services built up around my presence and it’s just—I don’t know what’s go-

ing to happen to it. There’s really been no kind of preparation for a very smooth transition. So, I worry about that. (16, USI Faculty in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

For example, a sustainability plan in the gynecology/oncology program was developed, driven by USI faculty, but did not come to fruition, partly due to a lack of flexibility in the planning:

They sent out a couple of people to do maternal fetal medicine fellowships in England…. So, I sort of—one is sort of coming back and he’ll be at RMH [Rwanda Military Hospital]. The other one, we thought was coming back would be at CHUK, but he extended a year probably to do research. Two more are going. For maternal fetal medicine, there is a plan in place. There was. There kind of always was. Once you sort of picked the two best ones from our initial trainees, and that was the plan…. When something gets thrown into the loop but doesn’t happen—there’s no budget for this stuff. (17, USI Faculty in Obstetrics and Gynecology)

The midterm review also reported there were no formal planning exercises to facilitate the phasing out of USI faculty and ensure a permanent faculty pipeline for a sustainable health system as the HRH Program time lines evolved (MOH, 2016b). A general practitioner working at CHUB observed that

since [USI faculty’s] departure, the main thing that is affecting us is the fact that we have junior specialists who have not yet acquired enough experience for them to train the generation behind them, we do not have people who are able to train those who would replace them. That is the main issue. (61, General Practitioner Not Trained in the HRH Program)

Finally, building local ownership over the HRH Program as a means of continuing it after the end of PEPFAR or other external funding was viewed as being hampered by changes in MOH leadership and leaders’ accompanying management style:

I think when we started to work on HRH at the very beginning with Dr. Richard Sezibera, who was minister at the time, in a very collaborative way with different partners. I think we were trying to involve everyone. Then Dr. Binagwaho came in and a lot more hands-on in her approach. She is very smart and a remarkable person, but she … very direct and very top-down in her management

style … a lot of Rwandan institutions or even partners in Rwanda couldn’t say “no,” or … have an open discussion about pros and cons, about things to consider, about anything really. And people, you know, heads of institutions or heads of departments in local institutions, in Rwandan institutions, they just went with it but they couldn’t really say “no,” and they didn’t really foster a sense of ownership within institutions. They were just kind of took what they were told and went with it. But I know from my context with them, a lot of them were critical and never really accepted the HRH Program. (22, Non-Government of Rwanda HRH Program Administrator)

CONCLUSIONS

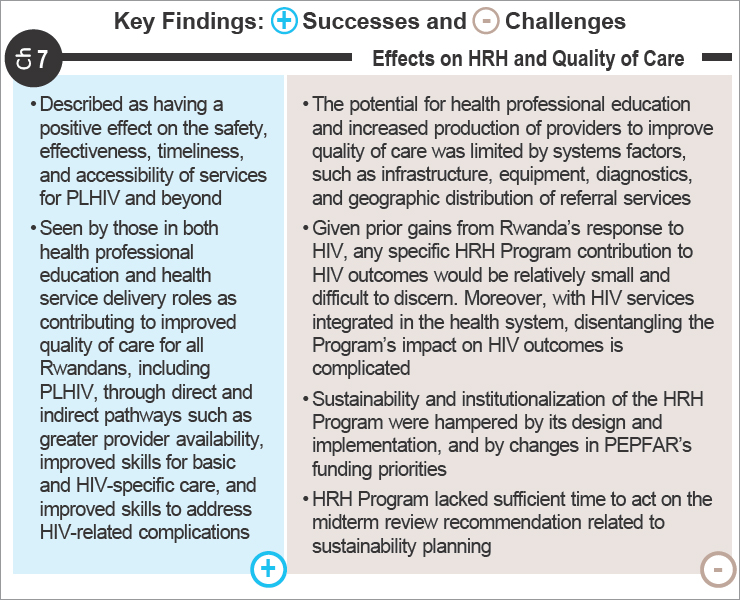

Program Impact

Using the IOM dimensions of quality as a frame, the HRH Program investment had a qualitative impact on the safety, effectiveness, timeliness, and accessibility of services for PLHIV and beyond. A small amount of qualitative data indicates that there may have been some contributions to improving equity in care and reducing stigmatization for PLHIV. The HRH Program was seen by those in both health professional education and health service delivery roles as contributing to improving quality of care for all Rwandans, including PLHIV, through direct and indirect pathways (greater provider availability, basic skills, HIV care-specific skills, and skills to address HIV-related complications).

The relationship between HRH training and patient-level outcomes is well documented in newborn survival, postpartum hemorrhage, surgical outcomes, and health care–associated infections (Aiken et al., 2003; Gomez et al., 2018; Grayson et al., 2018; Nelissen et al., 2017). For example, in critical care and emergency services, the presence of advanced practice nurses has been shown to have a positive impact on patient outcomes and may improve efficiencies (Woo et al., 2017). In HIV, there is less evidence linking the relationship between health professional education and PLHIV outcomes. However, there is evidence pointing to community health workers’ role in the provision of HIV care and improved outcomes for PLHIV, including psychosocial support and viral load suppression, yet these were not a part of the HRH Program (Han et al., 2018; Kenya et al., 2013).

As noted in the revised causal pathway (see Figure 7-3), the potential for health professional education and increased production of providers to improve quality of care is limited by other systems factors that affect quality (such as overall health worker density, infrastructure and diagnostics, and geographic and transportation-related barriers) (Farahani et al., 2016;

Lankowski et al., 2014; Mashamba-Thompson et al., 2017). For example, research from Tanzania found that at the facility level, increased loss to follow-up was associated with delays in testing and laboratory results, limited access to nutritional services, and poor patient flow (Rachlis et al., 2016).

Rwanda had made notable achievements in HIV service provision prior to the HRH Program. Successes included high rates of ART initiation, low loss to follow-up and mortality prior to initiation, and high retention rates (Teasdale et al., 2015). The implementation of the Treat All approach for HIV-infected children in 2012, in which all HIV-positive children under 5 years were initiated on combination ART, has positively affected pediatric outcomes in Rwanda, including growth, retention, and viral load suppression (Arpadi et al., 2019). The Treat All approach for all HIV-positive patients was implemented in 2016. Given these gains, the HRH Program’s contribution to HIV outcomes was relatively small. Considering that HIV services were integrated in the health system, as per health-sector policies and plans, disentangling the Program’s impact on HIV outcomes is further complicated.

Long-Term HRH Needs for PLHIV

The potential impact of the HRH Program on other health outcomes for PLHIV, including noncommunicable diseases, could not be determined by this evaluation. Although the Program invested in building a cadre of specialists, there did not appear to be an expansion of specialist cadres skilled to address the noncommunicable disease needs of PLHIV on long-term treatment, such as cardiologists or nephrologists. Evidence points to the need for future HRH planning to ensure the evolving health needs of an HIV population are met.

Recent population-based surveys from Tanzania and Uganda have shown that cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and other components of metabolic syndrome, are at least as prevalent in HIV populations as in the general population (Gaziano et al., 2017; Kavishe et al., 2015). Benjamin and colleagues (2016) demonstrated a double burden in Malawi, with traditional risk factors contributing to higher stroke risk in older PLHIV, while HIV status conferred higher risk among younger persons, especially those initiating ART within the 6 months prior to stroke onset. This finding suggests that immune reconstitution after immunodeficiency may require different clinical management strategies than those associated with traditional vascular risk factors for stroke (Benjamin et al., 2017).

Furthermore, PLHIV are at increased risk of kidney disease. With the widespread use of ART, HIV-associated nephropathy has become less

common, but the prevalence of other kidney diseases has increased, and long-term exposure to ART has the potential to cause or exacerbate kidney injury (Swanepoel et al., 2018). Among adult PLHIV initiated on ART in Zambia, renal insufficiency, even when mild, has been associated with increased mortality risk (Mulenga et al., 2008). A number of subsequent studies have assessed the prevalence of renal dysfunction among PLHIV in Africa starting ART, most of which show improvement in renal function after ART initiation for those with baseline renal dysfunction, including those initiating tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which has known nephrotoxicity and is a common component of first-line ART for many countries in the region (Chikwapulo et al., 2018; De Waal et al., 2017; Deckert et al., 2017; Mulenga et al., 2014). Yet, studies with 12–24 months’ follow-up have shown small but steady declines in estimated glomerular filtration rates for some patients exposed to TDF, particularly those with initial normal renal function (Chikwapulo et al., 2018; De Waal et al., 2017; Mulenga et al., 2014). As national ART guidelines across the region adapt to World Health Organization recommendations for earlier ART initiation, the increased duration of exposure to ART may shift the risk–benefit balance for kidney health (Swanepoel et al., 2018).

The resources and services needed for monitoring and managing renal and cardiovascular diseases among PLHIV in sub-Saharan Africa are, to date, insufficient. Preventative and treatment strategies for addressing these and other chronic diseases are needed, particularly among aging populations. The successful integration of HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa may offer critical insights into leveraging improvements in primary health care services, either through horizontal integration or within HIV health care delivery.

Sustainability and Institutionalization

Sustainability and institutionalization of the HRH Program were significantly hampered by the Program’s design and implementation, and by PEPFAR’s changes in funding priorities. There was general agreement among respondents that prolonged engagement of USI faculty in an intensive twinning program was not the desired outcome, but there was also recognition that there had been insufficient time to institutionalize the ability to continually update curricula and teaching methodologies at the University of Rwanda. The HRH Program’s midterm review also pointed to the need for improved sustainability planning, but PEPFAR’s decision to end funding before the planned end of the Program limited the MOH’s ability to act on this recommendation.

REFERENCES

Abbott, P., R. Sapsford, and A. Binagwaho. 2017. Learning from success: How Rwanda achieved the Millennium Development Goals for health. World Development 92:103–116.

Aiken, L. H., S. P. Clarke, R. B. Cheung, D. M. Sloane, and J. H. Silber. 2003. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA 290(12):1617–1623.

Arpadi, S., M. Lamb, I. N. Nzeyimana, G. Vandebriel, G. Anyalechi, M. Wong, R. Smith, E. D. Rivadeneira, E. Kayirangwa, S. S. Malamba, C. Musoni, E. H. Koumans, M. Braaten, and S. Nsanzimana. 2019. Better outcomes among HIV-infected Rwandan children 18–60 months of age after the implementation of “Treat All.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 80(3):e74–e83.

Bendavid, E., D. Stauffer, E. Remera, S. Nsanzimana, S. Kanters, and E. J. Mills. 2016. Mortality along the continuum of HIV care in Rwanda: A model-based analysis. BMC Infectious Disease 16(1):728.

Benjamin, L. A., E. L. Corbett, M. D. Connor, H. Mzinganjira, S. Kampondeni, A. Choko, M. Hopkins, H. C. Emsley, A. Bryer, B. Faragher, R. S. Heyderman, T. J. Allain, and T. Solomon. 2016. HIV, antiretroviral treatment, hypertension, and stroke in Malawian adults: A case-control study. Neurology 86(4):324–333.

Benjamin, L. A., T. J. Allain, H. Mzinganjira, M. D. Connor, C. Smith, S. Lucas, E. Joekes, S. Kampondeni, K. Chetcuti, I. Turnbull, M. Hopkins, S. Kamiza, E. L. Corbett, R. S. Heyderman, and T. Solomon. 2017. The role of human immunodeficiency virus-associated vasculopathy in the etiology of stroke. Journal of Infectious Diseases 216(5):545–553.

Binagwaho, A., I. Kankindi, E. Kayirangwa, J. P. Nyemazi, S. Nsanzimana, F. Morales, R. Kadende-Kaiser, K. W. Scott, V. Mugisha, R. Sahabo, C. Baribwira, L. Isanhart, A. Asiimwe, W. M. El-Sadr, and P. L. Raghunathan. 2016. Transitioning to country ownership of HIV programs in Rwanda. PLoS Medicine 13(8):e1002075.

Chikwapulo, B., B. Ngwira, J. B. Sagno, and R. Evans. 2018. Renal outcomes in patients initiated on tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-based antiretroviral therapy at a community health centre in Malawi. International Journal of STD and AIDS 29(7):650–657.

De Waal, R., K. Cohen, M. P. Fox, K. Stinson, G. Maartens, A. Boulle, E. U. Igumbor, and M. A. Davies. 2017. Changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate over time in South African HIV-1-infected patients receiving tenofovir: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of the International AIDS Society 20(1):21317.

Deckert, A., F. Neuhann, C. Klose, T. Bruckner, C. Beiersmann, J. Haloka, M. Nsofwa, G. Banda, M. Brune, H. Reutter, D. Rothenbacher, and M. Zeier. 2017. Assessment of renal function in routine care of people living with HIV on ART in a resource-limited setting in urban Zambia. PLoS One 12(9):e0184766.

Donovan, P. 2002. Rape and HIV/AIDS in Rwanda. Lancet 360:s17–s18.

Farahani, M., N. Price, S. El-Halabi, N. Mlaudzi, K. Keapoletswe, R. Lebelonyane, E. B. Fetogang, T. Chebani, P. Kebaabetswe, T. Masupe, K. Gabaake, A. F. Auld, O. Nkomazana, and R. Marlink. 2016. Impact of health system inputs on health outcome: A multilevel longitudinal analysis of Botswana national antiretroviral program (2002-2013). PLoS One 11(8):e0160206.

Gaziano, T. A., S. Abrahams-Gessel, F. X. Gomez-Olive, A. Wade, N. J. Crowther, S. Alam, J. Manne-Goehler, C. W. Kabudula, R. Wagner, J. Rohr, L. Montana, K. Kahn, T. W. Barnighausen, L. F. Berkman, and S. Tollman. 2017. Cardiometabolic risk in a population of older adults with multiple co-morbidities in rural South Africa: The HAALSI (Health and Aging in Africa: Longitudinal Studies of INDEPTH communities) study. BMC Public Health 17(1):206.

Gomez, P. P., A. R. Nelson, A. Asiedu, E. Addo, D. Agbodza, C. Allen, M. Appiagyei, C. Bannerman, P. Darko, J. Duodu, F. Effah, and H. Tappis. 2018. Accelerating newborn survival in Ghana through a low-dose, high-frequency health worker training approach: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18(1):72.

Grayson, M. L., A. J. Stewardson, P. L. Russo, K. E. Ryan, K. L. Olsen, S. M. Havers, S. Greig, and M. Cruickshank. 2018. Effects of the Australian national hand hygiene initiative after 8 years on infection control practices, health-care worker education, and clinical outcomes: A longitudinal study. Lancet Infectious Diseases 18(11):1269–1277.

Guaraldi, G., and F. J. Palella, Jr. 2017. Clinical implications of aging with HIV infection: Perspectives and the future medical care agenda. AIDS 31(Suppl 2):S129–S135.

Han, H. R., K. Kim, J. Murphy, J. Cudjoe, P. Wilson, P. Sharps, and J. E. Farley. 2018. Community health worker interventions to promote psychosocial outcomes among people living with HIV-a systematic review. PLoS One 13(4):e0194928.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kavishe, B., S. Biraro, K. Baisley, F. Vanobberghen, S. Kapiga, P. Munderi, L. Smeeth, R. Peck, J. Mghamba, G. Mutungi, E. Ikoona, J. Levin, M. A. Bou Monclus, D. Katende, E. Kisanga, R. Hayes, and H. Grosskurth. 2015. High prevalence of hypertension and of risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs): A population based cross-sectional survey of NCDs and HIV infection in northwestern Tanzania and southern Uganda. BMC Medicine 13:126.

Kenya, S., J. Jones, K. Arheart, E. Kobetz, N. Chida, S. Baer, A. Powell, S. Symes, T. Hunte, A. Monroe, and O. Carrasquillo. 2013. Using community health workers to improve clinical outcomes among people living with HIV: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behavior 17(9):2927–2934.

Koethe, J. R. 2017. Adipose tissue in HIV infection. Comprehensive Physiology 7(4):1339–1357.

Lankowski, A. J., M. J. Siedner, D. R. Bangsberg, and A. C. Tsai. 2014. Impact of geographic and transportation-related barriers on HIV outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. AIDS Behavior 18(7):1199–1223.

Mashamba-Thompson, T. P., R. L. Morgan, B. Sartorius, B. Dennis, P. K. Drain, and L. Thabane. 2017. Effect of point-of-care diagnostics on maternal outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Point of Care 16(2):67–77.

MDG (Millennium Development Goals) Monitor. 2015. Fact sheet on current MDG progress of Rwanda (Africa). https://www.mdgmonitor.org/mdg-progress-rwanda-africa (accessed October 10, 2019).

MOH (Ministry of Health). 2009a. Health sector strategic plan: July 2009–June 2012. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2009b. National strategic plan on HIV and AIDS 2009–2012. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2012. Third health sector strategic plan: July 2012–June 2018. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2013. National guidelines for prevention and management of HIV, STIs & other blood borne infections. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2016a. Annual health statistics booklet, 2016. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

MOH. 2016b. Rwanda Human Resources for Health Program midterm review report (2012–2016). Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health. (Available for request by the National Academies Public Access Records Office [paro@nas.edu] or via https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/managerequest.aspx?key=HMD-BGH-17-08.)

MOH. 2018. Rwanda HIV and AIDS national strategic plan 2013–2018: Extension: 2018–2020. Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Health.

Mulenga, L. B., G. Kruse, S. Lakhi, R. A. Cantrell, S. E. Reid, I. Zulu, E. M. Stringer, Z. Krishnasami, A. Mwinga, M. S. Saag, J. S. Stringer, and B. H. Chi. 2008. Baseline renal insufficiency and risk of death among HIV-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS 22(14):1821–1827.

Mulenga, L., P. Musonda, A. Mwango, M. J. Vinikoor, M. A. Davies, A. Mweemba, A. Calmy, J. S. Stringer, O. Keiser, B. H. Chi, and G. Wandeler. 2014. Effect of baseline renal function on tenofovir-containing antiretroviral therapy outcomes in Zambia. Clinical Infectious Diseases 58(10):1473–1480.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2018. Crossing the global quality chasm: Improving health care worldwide. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nelissen, E., H. Ersdal, E. Mduma, B. Evjen-Olsen, J. Twisk, J. Broerse, J. van Roosmalen, and J. Stekelenburg. 2017. Clinical performance and patient outcome after simulation-based training in prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage: An educational intervention study in a low-resource setting. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 17(1):301.

NISR (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda), MOH (Ministry of Health), and ICF International. 2016. Rwanda demographic and health survey 2014–15. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Ministry of Health, and ICF International.

Nsanzimana, S., K. Prabhu, H. McDermott, E. Karita, J. I. Forrest, P. Drobac, P. Farmer, E. J. Mills, and A. Binagwaho. 2015. Improving health outcomes through concurrent HIV program scale-up and health system development in Rwanda: 20 years of experience. BMC Medicine 13(1):216.

Nsanzimana, S., E. Remera, M. Ribakare, T. Burns, S. Dludlu, E. J. Mills, J. Condo, H. C. Bucher, and N. Ford. 2017. Phased implementation of spaced clinic visits for stable HIV-positive patients in Rwanda to support Treat All. Journal of the International AIDS Society 20(S4):21635.

PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief). 2018. 2018 annual report to Congress. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy.

PEPFAR Rwanda. 2019. Rwanda country operational plan (COP) 2019 strategic direction summary. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy.

Rachlis, B., G. Bakoyannis, P. Easterbrook, B. Genberg, R. S. Braithwaite, C. R. Cohen, E. A. Bukusi, A. Kambugu, M. B. Bwana, G. R. Somi, E. H. Geng, B. Musick, C. T. Yiannoutsos, K. Wools-Kaloustian, and P. Braitstein. 2016. Facility-level factors influencing retention of patients in HIV care in East Africa. PLoS One 11(8):e0159994.

Ross, J., J. D. Sinayobye, M. Yotebieng, D. R. Hoover, Q. Shi, M. Ribakare, E. Remera, M. A. Bachhuber, G. Murenzi, V. Sugira, D. Nash, K. Anastos, and for Central Africa leDEA. 2019. Early outcomes after implementation of Treat All in Rwanda: An interrupted time series study. Journal of the International AIDS Society 22(4):e25279.

RPHIA (Rwanda Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment). 2019. RPHIA 2018–2019 summary sheet. Kigali, Rwanda: PHIA Project.

Swanepoel, C. R., M. G. Atta, V. D. D’Agati, M. M. Estrella, A. B. Fogo, S. Naicker, F. A. Post, N. Wearne, C. A. Winkler, M. Cheung, D. C. Wheeler, W. C. Winkelmayer, and C. M. Wyatt. 2018. Kidney disease in the setting of HIV infection: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney International 93(3):545–559.

Teasdale, C. A., C. Wang, U. Francois, J. Ndahimana, M. Vincent, R. Sahabo, W. M. El-Sadr, and E. J. Abrams. 2015. Time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy among patients who are ART eligible in Rwanda: Improvement over time. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 68(3):314–321.

UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS). 2018a. AIDSinfo. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. aidsinfo.unaids.org (accessed August 31, 2019).

UNAIDS. 2018b. Country factsheets Rwanda 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/rwanda (accessed February 5, 2020).

Uwizeye, G., D. Mukamana, M. Relf, W. Rosa, M. J. Kim, P. Uwimana, H. Ewing, P. Munyiginya, R. Pyburn, N. Lubimbi, A. Collins, I. Soule, K. Burke, J. Niyokindi, and P. Moreland. 2018. Building nursing and midwifery capacity through Rwanda’s Human Resources for Health Program. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 29(2):192–201.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2017. Maternal mortality ratio (per 100,000 live births). http://gamapserver.who.int/gho/interactive_charts/mdg5_mm/atlas.html (accessed November 8, 2019).

Woo, B. F. Y., J. X. Y. Lee, and W. W. S. Tam. 2017. The impact of the advanced practice nursing role on quality of care, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost in the emergency and critical care settings: A systematic review. Human Resources for Health 15(1):63.

This page intentionally left blank.