7

Additional Concerns Related to the Use of Compounded Topical Pain Creams

Previous chapters described how topical pain creams are often lauded for allowing clinicians to treat pain through multimodal actions, thus providing a greater degree of versatility than oral dosage forms (Branvold and Carvalho, 2014). Having said this, several medications for managing pain already have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved topical formulations readily available in pharmacies (e.g., capsaicin, clonidine, lidocaine, diclofenac) (FDA, 2020). In other unique clinical circumstances in which pain cannot be managed by any of the available FDA-approved products, FDA regulations allow for medications to manage pain to be compounded for an individual patient.1 While compounded topical pain creams are options in the pain management toolbox, it is critical to note that compounded medications are not necessarily safer or more effective alternatives to commercial FDA-approved products. See Chapter 6 for a review of the current evidence on the safety and effectiveness of common compounded topical pain creams.

This chapter provides an overview of certain additional risks and concerns associated with the use of compounded topical pain creams, many of which arise because of the unique regulatory landscape and minimal oversight for these preparations (see Chapter 4 for more details about gaps and opportunities in regulation and oversight). In this chapter, the committee outlines concerns related to inadequate training and expertise for individuals who compound medications, inadequate training and guidance

___________________

1 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

for clinicians who prescribe compounded medications, and safety concerns and potential financial risks for patients.

INADEQUATE TRAINING AND EXPERTISE FOR INDIVIDUALS WHO COMPOUND

Licensed pharmacists, technicians supervised by a licensed pharmacist, and licensed physicians who compound in their own clinics are permitted to prepare compounded formulations under the auspices of state licensure and oversight (see Chapter 4).2 However, there is reason for concern that certain individuals who compound may have inadequate training and expertise to ensure that preparations are safe and effective.

Required Knowledge and Practical Competencies for Individuals Who Compound

Traditionally, individuals who compound are required to have formal education and a foundational knowledge in a range of scientific disciplines related to chemistry, pharmacology, and biology. Over the past few decades, however, demand for compounded medications has escalated, leading to a concomitant demand for pharmacists who are trained and experienced in the practice of compounding on a larger scale. Meeting this demand is complicated by the increasingly sophisticated and technical procedures and formulations required to create the customized dosage forms and new medication therapies that are emerging (Hinkle and Newton, 2004). See Chapter 5 for an additional discussion on the art and science of compounding.

The practice of pharmacy has shifted over the past century from compounding to dispensing FDA-approved medications (Sellers and Utian, 2012). When commercial drug production began taking over the market in the 1960s and 1970s (Newton, 2003), education about compounding practices in pharmacy schools began declining. Indeed, much compounding pedagogy has now been phased out of pharmacy school curricula in favor of clinical pharmacy instruction (Kochanowska-Karamyan, 2016). Today,

___________________

2 Section 503A of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) mandates that compounding be performed by a licensed pharmacist or licensed physician, and under Section 503B, an individual who compounds may be a licensed pharmacist or someone under the supervision of a licensed pharmacist. USP <795> goes beyond the FDCA, recommending that anyone who compounds (1) be familiar with the United States Pharmacopeia’s Pharmacists’ Pharmacopeia and other publications that may be relevant, including the ability to interpret Material Safety Data Sheets; (2) be familiar with standard operating procedures related to compounding; and (3) be trained in the storage, handling, and disposal of hazardous drugs if they are involved in the compounding of hazardous drugs (Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9; USP, 2018).

compounding instruction is highly variable, and many pharmacy schools do not offer any didactic or practical education on compounding (Shrewsbury et al., 2012).3 Pharmacy schools that do teach compounding often have inadequate resources and facilities and deliver instruction without standardized compounding curricula (Shrewsbury et al., 2012). Consequently, many pharmacists practicing today may not adequately understand the effect on safety and efficacy of each ingredient in a compounded preparation. In addition to theoretical knowledge, they also need practical, hands-on training in the skills needed to create compounds that are consistently and accurately prepared to ensure continuity of patient care (USP, 2008).

To develop and retain the practical skills and theoretical knowledge required, studies suggest that pharmacy students should receive more objective and quantitative evaluation of their compounding competency skills (Kadi et al., 2005) and regular, hands-on compounding instruction integrated throughout the curricula (Eley and Birnie, 2006; Mudit and Alfonso, 2017), as recommended by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Sections Compounding Task Force (Shrewsbury et al., 2012).4 Compounding pharmacists would also benefit from education that extends beyond the basic skills, but relatively few currently avail themselves of specialized training or higher certification (Schommer et al., 2008). Organizations such as the Professional Compounding Centers of America and the American College of Apothecaries offer classes and certification programs (ACA, 2020; Newton, 2003; PCCA, 2020), but training on compounding sterile preparations is mostly imparted through on-the-job experience (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).5

The evidence of minimal and unstandardized compounding instruction in pharmacy schools is cause for substantial concern as to whether current and future compounders have the requisite expertise to optimize formulations. Particular concern is warranted about the safety and effectiveness of compounded topical pain creams, given the vast range of options available

___________________

3 It is notable that the written North American Pharmacist Licensing Examination includes compounding among its evaluated competencies (NAPLEX, 2019); however, at the time of this report, only two U.S. states require practical examination in compounding for licensure as a pharmacist: Georgia and New York (McBane et al., 2019).

4 It is important to note that formulation scientists and compounding pharmacists are not one and the same. Formulation science is the field of pharmaceutical science that is not commonly offered in the standard pharmacy school curriculum (American Chemical Society, 2020), and there is no requirement for those who compound to gain explicit expertise in this field. Topical pain creams that are compounded by personnel without the requisite knowledge and training in tests for potency, purity, quality, and bioavailability are said to be a public health risk (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016).

5 Starting in fall 2019, the Board of Pharmacy Specialties began offering an exam for pharmacists to become accredited in Compounded Sterile Preparations, though the specialty has yet to receive official recognition (Board of Pharmacy Specialties, 2020).

for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients. Chapter 5 examines formulation science and its critical role in the design, development, manufacturing, and testing of pharmaceutical products and preparations.

INADEQUATE TRAINING AND GUIDANCE FOR CLINICIANS WHO PRESCRIBE COMPOUNDED MEDICATIONS

Evidence suggests that some prescribers are not sufficiently educated to properly administer and monitor the full spectrum of therapeutic medicines in their pain management toolbox (Lechenfeldt and Hall, 2018). Specifically, clinicians who prescribe compounded topical pain creams may not be adequately educated about the complex practice of compounding, the potential risks it can entail, or the lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of many compounded preparations.6 Furthermore, there is a dearth of clinical guidance and best practices to aid clinicians in prescribing these preparations. That void has likely contributed to the emergence of online prefilled prescription pads used to market compounded topical pain creams to clinicians and patients, which are cause for additional concern.

Inadequate Compounding Education in Medical School Curricula

The amount of time devoted to pharmacotherapy and compounding education in medical schools is not generally commensurate with the increasing use and complexity of compounded medications. In fact, evidence suggests that formal pharmacotherapy education has decreased in recent years (Wiernik, 2015).7 Medical students would also benefit more from integrated, practical pharmacological training, such as work experience with clinical pharmacologists,8 to complement their theoretical knowledge (Lechenfeldt and Hall, 2018). Other prescribing clinicians (e.g., physician assistants, nurse practitioners) may receive even less training given their more condensed school curriculum compared with medical school.

Given that prescribers themselves are permitted to compound preparations in their offices, inadequate compounding education in medical schools is cause for concern. As briefly mentioned in Chapter 4, the scope of

___________________

6 Additional evidence indicates that medical schools rarely assess the performance of their graduates in prescribing practices, with one study suggesting that many new clinicians feel unprepared in their prescribing skills (Lechenfeldt and Hall, 2018).

7 In an informal poll of the chairs from 39 pharmacology schools in the United States, 35 of the chairs reported that formal training in pharmacology for medical students has decreased in recent years, and 11 chairs reported that the number of faculty who have appropriate training has also decreased (Wiernik, 2015).

8 However, the number of clinical pharmacologists is limited; there are only four accredited clinical pharmacology fellowship programs in the United States (ACCP, 2019).

clinician compounding is largely unknown to state and federal regulators, though it is likely more frequent in certain specialties (GAO, 2016). Clinicians who compound are required to follow the federal 503A regulations and any applicable state laws (NABP, 2017),9 but a 2016 survey found that only nine states had laws, regulations, or policies specific to physicians or other nonpharmacists who compound (GAO, 2016).

All compounding performed by physicians is regulated by state boards of medicine, but two national survey reports in 2016 suggested that many of those boards are not actively overseeing physician compounding (GAO, 2016; The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016). Moreover, the reports found that compounding standards to ensure quality and safety are rarely applied or enforced for compounding physicians as they are for compounding pharmacists. Among state regulators who oversee compounding, the reports noted widespread confusion about oversight of physician compounding and even about whether a regulatory body exists within certain states (GAO, 2016; The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016).

Lack of Clinical Guidance for Clinicians Who Prescribe or for Physicians Who Compound Topical Pain Creams

Very limited guidance is available for clinicians who prescribe or for licensed physicians who compound topical pain creams.10 In fact, the committee only found a single clinical guideline or suggested best practice for prescribing compounded preparations to potential patient populations: an algorithm published by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy to aid pharmacists (and presumably extrapolatable to prescribers) in evaluating the appropriateness of nonsterile compounded drugs for a patient (McBane et al., 2019). Based on this guidance, the following relevant questions are among those to consider when prescribing compounded preparations:

- Are FDA-approved alternatives available?

- Are there studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of the compounded preparation in the specific proposed use and route of administration?

- Is the preparation for a patient in a special population (e.g., pediatric, geriatric, pregnant women)?

___________________

9 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9; USP, 2018.

10 In contrast, the American Veterinary Medical Association has clear recommendations for practicing veterinarians to help minimize the risk of adverse events associated with the use of compounded preparations in animals. These recommendations include limiting the use of a compounded preparation to drugs for which safety, efficacy, and stability have been demonstrated in the specific compounded form in the target species. See https://www.avma.org/policies/veterinary-compounding (accessed December 10, 2019).

Based on this single piece of professional guidance, the committee’s understanding is that the ideal decision-based prescription process for compounded topical pain creams spans multiple steps. First, the prescribing clinician and patient discuss the patient’s needs, assess the patient’s current pain management plan, and consider whether available FDA-approved products are suitable to fulfill the patient’s clinical needs. If FDA-approved products are unavailable or unsuitable, the presumable next step is for the prescribing clinician to consult with a certified compounding pharmacist to determine whether a safe and effective prescription formulation exists or can be created, based on the pharmacist’s knowledge and expertise.

Once a prescription is written, the pharmacist is responsible for (1) compounding a preparation of acceptable strength, quality, and purity, and (2) ensuring that the compound has appropriate packaging and labeling in accordance with good pharmacy practices, official standards, and current scientific principles. When the patient picks up the prescription, it would be expected that the pharmacist would counsel the patient on instructions for use, risks, and safety precautions for that specific compounded preparation (USP, 2018). Unfortunately, because of lack of oversight and standardization in medical and pharmacy practice, it is unknown whether, how often, and to what degree any of these steps are taken. The lack of clinical guidelines and best practices for clinicians who prescribe compounding preparations or for physicians who compound products themselves raises great concerns with respect to the safety, quality, and effectiveness of the preparations dispensed to patients.

Use of Online Prescription Pads and Marketing

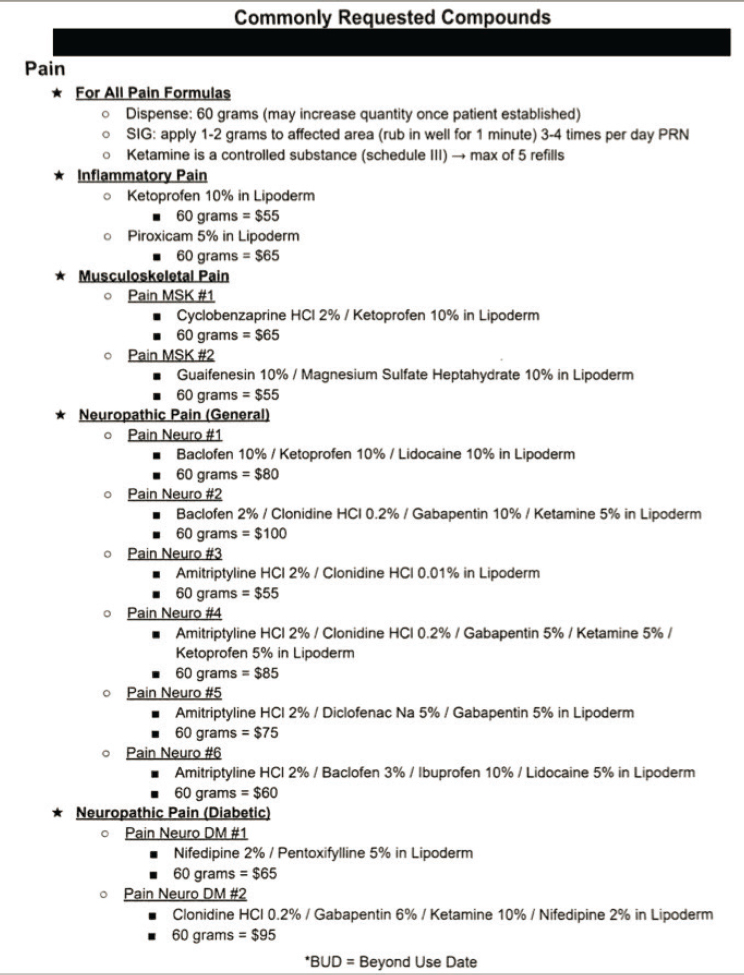

Ideally, the prescription for a compounded preparation is issued to a patient only after careful consideration of the patient’s specific needs and with reasonable expectation of effectiveness (AMA, 2016). However, this clinical practice is often difficult to achieve with the increasing complexity of new therapeutics and inadequate education and guidance for clinicians about the use of compounded preparations (Wiernik, 2015). As a potential consequence, paper- or web-based preformulated prescription forms for compounded topical pain preparations seem to appeal to prescribers by making the compounding prescription process “quick and easy.” These forms often list options for treating specific pain conditions and may offer preset ingredients or combinations at set or variable concentrations. In some cases, these forms are used as a marketing tool for compounded preparations to increase the volume of requests and sales (FDA, 2019b). Figure 7-1 is an example of a deidentified prescription pad that was distributed to physician offices in February 2019.

Although they promote a factor of convenience, no publicly available evidence suggests that compounding pharmacies develop these sample prescriptions with any rationale for formulations, doses, and dosage forms; the sample prescriptions also rarely include disclosures on efficacy, safety, or potential adverse effects.11 This gives rise to growing concern that clinicians may be “checking boxes” on these forms without adequate assessment or evaluation of the individual patient’s complex clinical needs.

Prefilled prescription pads are intended for prescribers’ use only, but reports of compounding pharmacies marketing compounded topical pain preparations directly to patients warrants further concern (FBI, 2018; Norton, 2019). As revealed in fraud cases brought against compounding pharmacies, there are instances of compounded topical pain preparations being prescribed to patients who maintained that they never requested nor discussed the use of the treatment with a pharmacist (FBI, 2018). This variability in initiating the prescription process calls into question the actual demand and utility of compounded topical pain creams.

Professional Risks for Prescribing Clinicians

Clinicians who prescribe a compounded medication that causes adverse effects can be exposed to liability, especially if an appropriate FDA-approved alternative is available (Gudeman, 2013). The provider is considered responsible for having selected the specific types and quantities of ingredients in the prescription (Sellers and Utian, 2012). When adverse events are caused by FDA-approved drugs, the prescribing clinician is typically protected by FDA’s approval process and background support from the commercial pharmaceutical company that manufactured the drug; prescribers of a compounded preparation that harms a patient are not similarly protected. Furthermore, malpractice insurance may not cover claims that involve non-FDA-approved compounded preparations (O’Brien et al., 2013).

Additional professional risks relate to potential conflicts of interest. Financial conflicts may arise when pharmacists or clinicians who are responsible for care of a patient also have a financial stake in the compounded preparations they prescribe or produce. Navigating conflicts of interest—particularly financial conflicts—is a particular concern with respect to compounded preparations, because regulatory oversight is limited and variably enforced. Congress has sought to address financial conflicts of interest through enhanced disclosure via the Physician Payments

___________________

11 As previously addressed in this report, individuals who compound are exempt from performing tests on the safety and efficacy of compounded preparations, in general, and based on the findings from the literature review in Chapter 6, there are limited data on the safety and effectiveness of APIs commonly used in compounded topical pain creams.

Sunshine Act, originally passed in 2010 as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,12 but it does not cover disclosure of payments and financial relationships between providers and compounding pharmacies or outsourcing facilities.

SAFETY CONCERNS FOR PATIENTS

From the patient’s perspective, compounded topical pain creams are associated with safety concerns including risks associated with unstandardized formulations, polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions, misuse of compounded preparations, and potential adverse events.

Unstandardized Formulations for Compounded Topical Pain Creams

Like all pain medication, each compounded topical pain cream has some potential for adverse effects or intolerance among certain populations of patients. The safety and efficacy risks associated with compounded topical pain creams are complex and difficult to assess, however. As discussed in Chapters 3, 4, and 5, a single compounded preparation may contain a large number of constituent components in a formulation, including APIs and inactive pharmaceutical ingredients (e.g., excipients, fillers).13 All of the components carry potential risks individually and in combination, particularly those with systemic absorption. Because of the ad hoc nature of compounding, the formulations of the preparations are not standardized across different compounding pharmacies, which introduces additional risks to the patient. These risks include potential exposure to novel formulations with no demonstrated evidence for safety and effectiveness as a topical treatment.

___________________

12 Social Security Act. § 1128G (42 U.S. Code 1320a-7h).

13 An excipient is a pharmacologically inert ingredient used in a drug product that lends various functional properties to the product (e.g., dosage form, taste masking, drug release).

Risks Associated with Polypharmacy and Drug–Drug Interactions

In addition to taking into account the lack of evidence on safety and effectiveness of nonstandardized formulations of compounded topical pain creams, prescribers must also consider potential safety risks to the patient associated with polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions when making treatment decisions (see Table 7-1). Compounded topical pain creams often include a combination of two or more APIs (NABP, 2019),14 which has potential safety risks. For example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac) and tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, doxepin) are commonly used to treat pain, but with systemic absorption, their concurrent use can increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and intracranial bleeding (HHS, 2019; Richlin, 1991; Shin et al., 2015). Another important consideration in treatment decisions is that many patients may concurrently use other oral medications in addition to compounded topical pain creams. Appendix G provides more information about the potential risks of polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions.

TABLE 7-1

Potential Drug–Drug Interactions for Select APIs (Oral Administration)

| Drug Product | Potentially Major or Life-Threatening Drug–Drug Interactions |

|---|---|

| Amitriptilyne | Concurrent use of NSAIDS and TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of bleeding. Concurrent use of CYCLOBENZAPRINE and TRYCYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS may result in increased risk of serotonin syndrome. |

| Baclofen | Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and CNS DEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of respiratory and CNS depression. |

| Carbamazepine | Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and SEROTONERGIC CYP3A4 INDUCERS may result in increased risk of serotonin syndrome and reduced TRAMADOL plasma concentrations. |

___________________

14 In a small survey of national pharmacies, the Professional Compounding Centers of America estimated that greater than 80 percent of dispensed compounded topical pain creams contained two or more APIs and greater than 50 percent contained three or more APIs.

| Drug Product | Potentially Major or Life-Threatening Drug–Drug Interactions |

|---|---|

| Clonidine | Concurrent use of DOXEPIN and CLONIDINE may result in decreased antihypersensitive effectiveness. |

| Clonidine HCI | Concurrent use of DOXEPIN and CLONIDINE may result in decreased antihypersensitive effectiveness. |

| Cyclobenzaprine | Concurrent use of CYCLOBENZAPRINE and TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS may result in an increased serotonin syndrome. Concurrent use of CYCLOBENZAPRINE and TRAMADOL may result in an increased risk of respiratory and CNS depression; increased risk of serotonin syndrome; an increased risk of paralytic ileus. |

| Dexamethasone | Concurrent use of CORTICOSTEROIDS and NSAIDS may result in an increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcer or bleeding. |

| Doxepin | Concurrent use of NSAIDS and TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of bleeding. Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and SEROTONERGIC AGENTS WITH ANTICHOLINGERIC PROPERTIES may result in increased risk of paralytic ileus; increased risk of serotonin syndrome. |

| Ketamine | Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and CNS DEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of respiratory and CNS depression. |

| Meloxicam | Concurrent use of MELOXICAM and NSAIDS AND SALICYLATES may result in increased risk of bleeding. Concurrent use of NSAIDS and TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of bleeding. |

| Memantine | Concurrent use of MEMANTINE and SELECTED NMETHYLDASPARATE ANTAGONISTS may result in increased adverse events of NmethylDasperate agonists. |

| Naproxen | Concurrent use of NSAIDS and TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of bleeding. Concurrent use of CORTICOSTEROIDS and NSAIDS may result in increased risk of gastrointestinal ulcer or bleeding. |

| Nifedipine | Concurrent use of NIFEDIPINE and CYP3A4 INDUCERS may result in decreased NIFEDIPINE exposure. |

| Orphenadrine | Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and CNS DEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of paralytic ileus; increased risk of respiratory and CNS depression. |

| Pentoxyfilline | Concurrent use of PENTOXYFILLINE and NSAIDS may result in an increased risk of bleeding. |

| Topiramate | Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and CNS DEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of respiratory and CNS depression. |

| Tramadol | Concurrent use of TRAMADOL and CNS DEPRESSANTS may result in an increased risk of respiratory and CNS depression. |

NOTE: CNS = central nervous system; NSAIDS = nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

SOURCE: Micromedex, 2019.

Misuse of Compounded Preparations

A patient’s lack of knowledge about a compounded preparation can lead to misuse, another associated safety risk. As discussed in Chapter 4, compounded preparations from 503A compounding pharmacies are not required to be dispensed with standardized product inserts. Although some compounding pharmacies do dispense inserts with compounded preparations, particularly those practicing in states that require compliance with USP <795>, patients are likely to receive variable information about the formulation (i.e., active and inactive ingredients), how to use the preparation, and the potential for adverse reactions (FDA, 2017). Many adverse events from topical compounded pain creams reported to FDA can be attributed to the patient misusing or overdosing creams, either on themselves or inadvertently on others through skin-to-skin transmission (FDA, 2019a). See Appendix F for a list of adverse events submitted to FDA between 2003 and 2018.

Advertising and marketing by 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities may characterize their compounded preparations—implicitly or explicitly—as safe and effective, thus implying incorrectly that the medications meet FDA-approval standards (FDA, 2017).15 Understandably, patients who are not aware of regulatory exceptions surrounding compounding may assume that compounded preparations undergo the same rigorous regulatory process as other medications prescribed by their clinicians. Patients may not even know that their medication is compounded or may not understand what compounding entails (Cowan, 2019). Moreover, many patients may not receive pharmacist counseling on the use of compounded preparations, particularly because many compounded medication prescriptions are delivered by mail or through online pharmacies (McPherson et al., 2019). This lack of awareness and education among patients further exacerbates safety concerns related to compounded preparations.

Patients would be better equipped to make their own risk–benefit assessments about using a compounded preparation if they were provided with information on its risks and potential adverse events and if they were made aware that compounded preparations have not been approved or tested by a regulatory agency. Similarly, including clear directions for use and storage of compounded drugs would likely reduce adverse events occurring from patient misuse.

___________________

15 FDA has sent warning letters to several compounders whom they have found to make unsubstantiated efficacy and superiority claims (Gardine, 2008; Vitillio, 2008).

Adverse Events Associated with the Use of Compounded Topical Pain Creams

As discussed in Chapter 4, little data are available on adverse events linked to compounded preparations, attributable in large part to limited federal and state-level regulations in place to document, monitor, and limit the use of compounded preparations associated with known or widespread adverse effects. In most cases, FDA may not become aware of adverse events unless a health care provider or state official notifies the agency (FDA, 2017). Studies suggest that patients, pharmacies, and clinicians will voluntarily report adverse events related to the use of the compounded preparations intermittently—if at all—so it stands to reason that a substantial number of adverse events go underreported (FDA, 2016; Kessler, 1993).

To gather additional data on adverse events, the committee submitted a data request to FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) in 2019 to review adverse events and case study reports involving compounded topical pain creams. See Appendix F for the detailed list of 38 adverse events that range from minor skin irritations to severe toxicity and an unfortunate death, and include suspected causes ranging from accidental misuse of the medication to API toxicity. However, owing to the voluntary nature of reporting and the limitations in the data entry process, it is uncertain whether these cases are a true representative sample of adverse effects related to use of compounded topical pain creams.16

Also in 2019, the committee submitted a data request to the American Association of Poison Control Centers to review potential concerns related to the safety of compounded topical pain creams. It was difficult to accurately track which reported events were related to FDA-approved

___________________

16 FDA identified 38 adverse events reports that related to the use of a compounded topical drug by reading through report descriptions of all entries marked as compounded. It is important to note that there may be other FAERS cases related to the use of compounded topical drugs, but if the necessary indication box for compounded mediations was not checked during the data entry process, then those cases would not be represented in the full dataset.

topical creams and which where relevant to exclusive compounded topical creams. In the end, the submitted request involved a search of the National Poison Data System (NPDS) for any reported events involving the committee’s specific APIs of interest used in topical (e.g., lotion, cream, gel) formulations. The data revealed that between 2014 and 2019, a total of 275 reported incidents were reported to the NPDS. The NPDS categorized 24 of those events as having a major effect, but none resulted in fatality. The vast majority (123) of these incidents were attributed to a general “unintentional” cause, meaning an overexposure or accidental exposure to the pain cream. Only 26 of these incidents were attributed to adverse reactions to APIs used (AAPCC, 2019).17

As illustrated by the NPDS data, it is important to remember that all medications, including FDA-approved topical pain cream products, are associated with a certain level of risk. For example, one man applied FDA-approved topical diclofenac gel to his back for back pain and, after spending prolonged time under the sun, developed a severe skin rash with blistering skin where the gel was applied (Akat, 2013). The FDA package insert for diclofenac gel—included with every prescription—warns that patients “should minimize or avoid exposure to natural or artificial sunlight on treated areas” (Endo Pharmaceuticals, 2016). A critical concern is that patients may not receive the same (or any) safety warnings when an FDA-approved product, such as diclofenac gel, is used in a compounded preparation in addition to other APIs. It is critical for clinicians and patients to understand that when an FDA-approved product is included in a compounded preparation, that product is no longer subject to the same regulatory labeling requirements it would have when dispensed alone in a noncompounded preparation.

In summary, as suggested by the data outlined above, it is often difficult to assess potential adverse effects or events related to the use or misuse of compounded preparations. As suggested in Chapter 4, this is likely caused, in part, by gaps in the regulation and oversight of compounded preparations. Because 503A compounding pharmacies are not required to collect or share adverse event data with FDA, without these data, it is difficult to accurately characterize the public health aspects of compounded medications. (See Box 4-3 in Chapter 4 for an additional discussion on adverse event reporting.) Additional efforts to increase the surveillance, data collection, and adverse event reporting for compounded topical pain creams is needed.

___________________

17 These data may include both FDA-approved products and compounded formulations. Certain cases included single-ingredient creams, while others included multi-ingredient pain creams. In addition, certain cases described the ingestion of solid dosage form and an exposure to topical product/preparation. These confounders prevent clear conclusions from being made.

POTENTIAL FINANCIAL RISKS FOR PATIENTS

Potential financial risks for patients are additional consequences of the limited data on the effectiveness of many compounded topical pain creams (discussed in Chapter 6), particularly in cases where patients or their insurance companies are charged high prices for untested and potentially ineffective compounded preparations. According to a retrospective analysis of prescription claims data, ingredients commonly used in compounded topical pain creams were the most expensive ingredients used in compounded drugs for adults by total cost billed in 2013 (McPherson et al., 2016).18

A recent survey of almost 500 patients of compounded preparations found that almost all (95 percent) were satisfied with every aspect of the therapy except for the cost (McPherson, 2019). Given that the average duration of compounded prescription use reported by the survey respondents was 30 months, costs incurred by patients can mount quickly (McPherson et al., 2019). The out-of-pocket costs to patients for compounded preparations in general and compounded pain creams specifically have not yet been well quantified. However, some survey data are available about the average out-of-pocket costs (McPherson et al., 2019):

- Average out-of-pocket cost of compounded prescription in general: $50 for insured patients; $116 for uninsured patients

- Average out-of-pocket cost for compounded medication in general: $93

- Average out-of-pocket cost for compounded pain medications specifically: $26

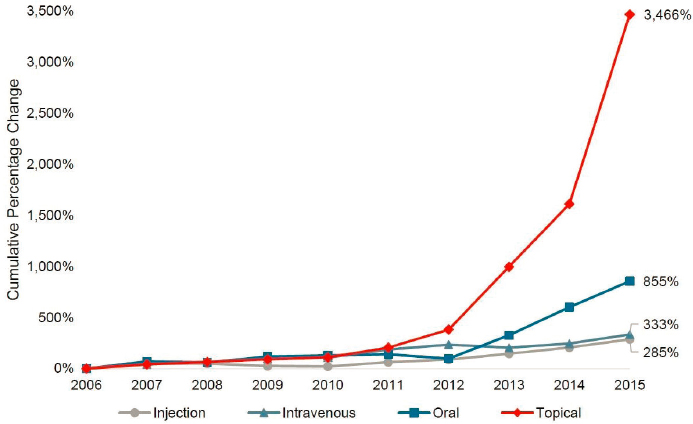

Additional information about compounded topical drug costs is available from Medicare Part D data, which show that annual spending for compounded topical drugs rose more than 3,400 percent between 2006 and 2015, with the largest increase seen in 2014 (see Figure 7-2). In 2006, topical drugs accounted for 9 percent of all compounded drug spending by Medicare Part D. By 2015, spending on compounded topical drugs had reached $224.3 million, representing 44 percent of total spending

___________________

18 The average cost of ingredients in compounded preparations in general increased from $308 to $710 (130 percent) between 2012 and 2013, while the average cost of ingredients in noncompounded prescriptions increased from $149 and $160 (7 percent) during the same period (McPherson et al., 2016). In response to the research interests of this report, the Professional Compounding Centers of America conducted a small survey to a limited number of pharmacies in their membership network and determined that the median costs for compounded topical pain creams was less than oral commercial products containing similar APIs (PCCA, 2019).

SOURCE: HHS OIG, 2016.

on compounded drugs. The costs rose dramatically during this period because the average cost of each prescription increased and the number of beneficiaries receiving these drugs increased. The average cost for each prescription grew by 720 percent from 2006 to 2015, from $40 to $331 (HHS OIG, 2016). For comparison, the average retail price for brand-name drugs increased by 188 percent during the same period (Schondelmeyer and Purvis, 2016). The dramatic shifts in the use of and spending on compounded preparations between 2006 and 2015 raised substantial concerns about fraud and patient safety (HHS OIG, 2016).

In 2015, TRICARE—the health insurance program for military personnel—discovered a nationwide compounded drug scheme that had resulted in an estimated $1.5 billion in fraudulent charges (Norton, 2019; Philpott, 2018). The majority of these schemes involved dispensing ointments or creams, with great variability in how the request for a prescription was initiated: by physicians, pharmacists, marketers, or even patients. Each of these prescriptions resulted in substantial charges to TRICARE that in some cases amounted to tens of thousands of dollars per prescription, depending on the number and type of APIs included in the compounded formulation. These compounded preparations were formulated with the intent of maximizing the amount that the pharmacist could charge to the insurer, rather than meeting patients’ needs (Philpott, 2018). In response to this

activity, the U.S. Department of Justice has brought enforcement actions against hundreds of defendants for fraud and kickback schemes involving billing Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE for compounded topical preparations (DOJ, 2017, 2018a,b,c; U.S. Attorney’s Office Eastern District of Arkansas, 2018). At the peak of this fraudulent activity, TRICARE paid about $500 million for compounded preparations in April 2015 (DoDIG, 2016). At the time of this committee’s report release, TRICARE reports that it typically receives about 20,000 claims per month for compounded preparations at a cost of $10–$15 million per year (Norton, 2019).

Mounting concerns of rising costs and potential fraud related to the prescribing practices for compounded drugs, including topical pain creams, have led to policies and procedures that have increased financial risks for patients who are prescribed these preparations. Several Medicare and TRICARE policies and procedures have been changed to incorporate fraud identification training and restrict coverage only to compounds that include FDA-approved ingredients (Chavez-Valdez, 2018; DoDIG, 2016). Many insurers and pharmacy benefit managers have instituted policies to decrease the number of claims for compounded preparations because of their concerns about safety, efficacy, cost, and lack of regulatory oversight (McPherson et al., 2016).

Patients have been adversely affected by these policy changes—particularly the exclusion of certain compounded preparations from insurance coverage and consequent increases in cost. For example, some patients may no longer have access to compounded topical pain creams they need to manage their pain, because the out-of-pocket costs are prohibitive. Even if patients can afford the out-of-pocket cost, they run the risk of paying high prices for compounded topical pain creams that have little or no evidence of safety and effectiveness. Given that these policy changes were driven by a lack of evidence about the safety and effectiveness of compounded preparations, expanding the evidence base would help to mitigate financial risks to patients.

REFERENCES

AAPCC (American Association of Poison Control Centers). 2019. National Poison Data System results for aggregate counts for compounded topical incidents. Available through the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Public Access File. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/assessment-of-the-available-scientific-data-regarding-the-safety-and-effectiveness-of-ingredients-used-in-compounded-topical-pain-creams (acccessed April 1, 2020).

ACA (American College of Apothecaries). 2020. American College of Apothocaries educational opportunities. https://acainfo.org/educational-opportunities (accessed February 27, 2020).

ACCP (American College of Clinical Pharmacy). 2019. Directory of residencies, fellowships, and graduate programs. https://www.accp.com/resandfel (accessed October 28, 2019).

Akat, P. B. 2013. Severe photosensitivity reaction induced by topical diclofenac. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 45(4):408–409.

AMA (American Medical Association). 2016. Principles of medical ethics, 9.6.6 prescribing & dispensing drugs & devices. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-9.pdf (accessed February 26, 2020).

American Chemical Society. 2020. Formulation chemistry. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/careers/college-to-career/chemistry-careers/formulation-chemistry.html (accessed February 28, 2020).

Board of Pharmacy Specialties. 2020. Accreditation. https://www.bpsweb.org/about-bps/accreditation (accessed March 4, 2020).

Branvold, A., and M. Carvalho. 2014. Pain management therapy: The benefits of compounded transdermal pain medication. Journal of General Practice 2:6. https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/pain-management-therapy-the-benefits-of-compounded-transdermal-pain-medication-2329-9126.1000188.php?aid=33304 (accessed December 13, 2019).

Chavez-Valdez, A. 2018. Medicare part D coverage of multi-ingredient compounds. http://www.ncpa.co/pdf/compoundmemo-080718.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

Cowan, P. 2019. Presentation to the assessment of the available scientific data regarding the safety and effectiveness of ingredients used in compounded topical pain creams meeting 2: American Chronic Pain Assocation topical cream survey. May 20. Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Quality/CompoundedPainCream/10_Cowan.pdf (accessed January 10, 2020).

DoDIG (U.S. Department of Defense Inspector General). 2016. Controls over compound drugs at the Defense Health Agency reduced costs substantially, but improvements are needed. https://www.dodig.mil/Reports/Compendium-of-Open-Recommendations/Article/1119293/controls-over-compound-drugs-at-the-defense-health-agency-reduced-costs-substan (accessed March 3, 2020).

DOJ (U.S. Department of Justice). 2017. Leader of $17 million health insurance fraud scheme ordered to prison. https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdtx/pr/leader-17-million-health-insurance-fraud-scheme-ordered-prison (accessed March 3, 2020).

DOJ. 2018a. Four plead guilty in multi-million dollar TRICARE scheme. https://www.justice.gov/usao-edar/pr/four-plead-guilty-multi-million-dollar-tricare-scheme (accessed March 3, 2020).

DOJ. 2018b. Southern District of Florida charges 124 individuals responsible for $337 million in false billing as part of national healthcare fraud takedown. https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/southern-district-florida-charges-124-individuals-responsible-337-million-false-billing (accessed March 3, 2020).

DOJ. 2018c. United States files false claims act complaint against compounding pharmacy, private equity firm, and two pharmacy executives alleging payment of kickbacks. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-files-false-claims-act-complaint-against-compounding-pharmacy-private-equity (accessed March 3, 2020).

Eley, J. G., and C. Birnie. 2006. Retention of compounding skills among pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 70(6):132.

Endo Pharmaceuticals. 2016. Voltaren gel (diclofenac sodium topical gel). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022122s006lbl.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation). 2018. Prescription for prison time: Fraudsters scammed government, private insurance companies out of $100 million. https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/compounding-pharmacy-fraud-081518 (accessed December 13, 2019).

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2016. MedWatch: Managing risks at the FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-information-consumers/medwatch-managing-risks-fda (accessed December 13, 2019).

FDA. 2017. FDA’s human drug compounding progress report: Three years after enactment of the Drug Quality and Security Act. https://www.fda.gov/media/102493/download (accessed December 11, 2019).

FDA. 2019a. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/questions-and-answers-fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers-public-dashboard (accessed March 3, 2020).

FDA. 2019b. Presentation to the Committee on March 25. Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Quality/CompoundedPainCream/2019-MAR-25.aspx (accessed March 3, 2020).

FDA. 2020. Orange book: Approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book (accessed March 3, 2020).

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2016. Drug compounding: FDA has taken steps to implement compounding law, but some states and stakeholders reported challenges. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681096.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

Gardine, T. D. 2008. Warning letter to Murray Avenue Apothecary in Philadelphia, PA, USA. https://web.archive.org/web/20121031091347/http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2008/ucm1048443.htm (accessed March 13, 2020).

Gudeman, J., M. Jozwiakowski, J. Chollet, and M. Randell. 2013. Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs in R&D 13(1):1–8.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2019. Pain management best practices. Inter-Agency Task Force report updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pain-mgmt-best-practices-draft-final-report-05062019.pdf (accessed April 7, 2020).

HHS OIG (Office of Inspector General). 2016. High Part D spending on opioids and substantial growth in compounded drugs raise concerns. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-16-00290.asp (accessed March 3, 2020).

Hinkle, A., and G. Newton. 2004. Compounding in the pharmacy curriculum: Beyond the basics. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding 8(3):181–185.

Kadi, A., D. Francioni-Proffitt, M. Hindle, and W. Soine. 2005. Evaluation of basic compounding skills of pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 69(4):69.

Kessler, D. A. 1993. Introducing Medwatch: A new approach to reporting medication and device adverse effects and product problems. JAMA 269(21):2765–2768.

Kochanowska-Karamyan, A. J. 2016. Pharmaceutical compounding: The oldest, most symbolic, and still vital part of pharmacy. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding 20(5):367–374.

Lechenfeldt, S., and L. M. Hall. 2018. Pharm.D.s in the midst of M.D.s and Ph.D.s: The importance of pharmacists in medical education. Medical Science Educator 28:259–261.

McBane, S. E., S. A. Coon, K. C. Anderson, K. E. Bertch, M. Cox, C. Kain, J. LaRochelle, D. R. Neumann, and A. M. Philbrick. 2019. Rational and irrational use of nonsterile compounded medications. Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy 2(2):189–197.

McPherson, T. 2019. Presentation to the committee on March 25. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Quality/CompoundedPainCream/2019-MAR-25.aspx (accessed February 27, 2020).

McPherson, T., P. Fontane, R. Iyengar, and R. Henderson. 2016. Utilization and costs of compounded medications for commercially insured patients, 2012-2013. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy 22(2):172–181.

McPherson, T., P. Fontane, and R. Bilger. 2019. Patient experiences with compounded medications. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association 59(5):670–677.

Micromedex. 2019. Electronic version: IBM Watson Health, Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. Subscription required to view. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com (accessed October 30, 2019).

Mudit, M., and L. F. Alfonso. 2017. Analytical evaluation of the accuracy and retention of compounding skills among PharmD students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81(4):64.

NABP (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy). 2017. National reports raise questions about oversight of drug compounding in physicians’ offices. Innovations 46(3):6–8.

NAPLEX (North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination). 2019. 2019 candidate application bulletin. https://nabp.pharmacy/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/NAPLEX-MPJE-Bulletin-October-2019.pdf (accessed December 11, 2019).

Newton, D. W. 2003. Compounding paradox: Taught less and practiced more. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 67(1):5.

Norton, E. 2019. Presentation to the Assessment of the Available Scientific Data Regarding the Safety and Effectiveness of Ingredients Used in Compounded Topical Pain Creams Meeting 1. March 25. Washington, DC. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-25-2019/first-meeting-of-the-committee-on-the-assessment-of-the-available-scientific-data-regarding-the-safety-and-effectiveness-of-ingredients-used-in-compounded-topical-pain-creams (accessed January 10, 2020).

O’Brien, Jr., D., I. Cohen, and D. Kennedy. 2013. Compounding pharmacies: A viable option, or merely a liability? PM&R Journal 5(11):974–981.

PCCA (Professional Compounding Centers of America). 2019. Presentation to committee on September 30, 2019. Washington, DC. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Quality/CompoundedPainCream/2019-SEP-30.aspx (accessed March 3, 2020).

PCCA. 2020. Education. https://www.pccarx.com/Education (accessed February 27, 2020).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2016. Best practices in state oversight of drug compounding. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/02/best_practices_for-state_oversight_of_drug_compounding.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP. 2018. State oversight of drug compounding. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/02/drug_safety_assesment_web.pdf (accessed March 3, 2020).

Philpott, T. 2018. TRICARE recoups $280 million so far from compound drug scams. https://www.military.com/militaryadvantage/2018/09/27/tricare-recoups-280-million-so-far-compound-drug-scams.html (accessed December 10, 2019).

Richlin, D. M. 1991. Nonnarcotic analgesics and tricyclic antidepressants for the treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 58(3):221–228.

Schommer, J. C., L. M. Brown, and E. M. Sogol. 2008. Work profiles identified from the 2007 pharmacist and pharmaceutical scientist career pathway profile survey. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 72(1):2.

Schondelmeyer, S. W., and L. Purvis. 2016. Trends in retail prices of brand name prescription drugs widely used by older Americans, 2006-2015. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2016-12/trends-in-retail-prices-dec-2016.pdf (accessed April 8, 2020).

Sellers, S., and W. H. Utian. 2012. Pharmacy compounding primer for physicians: Prescriber beware. Drugs 72(16):2043–2050.

Shin, J.-Y., M.-J. Park, S. H. Lee, S.-H. Choi, M.-H. Kim, N.-K. Choi, J. Lee, and B.-J. Park. 2015. Risk of intracranial haemorrhage in antidepressant users with concurrent use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Nationwide propensity score matched study. British Medical Journal 351:h3517.

Shrewsbury, R., S. Augustine, C. Birnie, K. Nagel, D. Ray, J. Ruble, K. Scolaro, and J. Athay Adams. 2012. Assessment and recommendations of compounding education in AACP member institutions. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 76(7):S9.

U.S. Attorney’s Office Eastern District of Arkansas. 2018. Four plead guilty in multi-million dollar TRICARE scheme. https://www.justice.gov/usao-edar/pr/four-plead-guilty-multi-million-dollar-tricare-scheme (accessed March 3, 2020).

USP (United States Pharmacopeia). 2008. <797> pharmaceutical compounding—Sterile preparations. In The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Rockville, MD: USP. https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-797 (accessed March 3, 2020).

USP. 2018. <795> pharmaceutical compounding—Nonsterile preparations. In The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Rockville, MD: USP. https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-795 (accessed March 3, 2020).

Vitillio, O. D. 2008. Warning letter to American Hormones, Inc. in Jamaica, NY, USA. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112024717/http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/PharmacyCompounding/ucm155170.htm (accessed March 13, 2020).

Wiernick, P. H. 2015. A dangerous lack of pharmacology education in medical and nursing schools: A policy statement from the American College of Clinical Pharmacology. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 55(9):953–954.

This page intentionally left blank.