4

Gaps in Regulation, Oversight, and Surveillance

CURRENT REGULATION AND LEGISLATION

Compounded drugs have long been part of the medical armamentarium for serving patients with unique clinical needs that otherwise cannot be addressed with drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, FDA does not have the regulatory authority to verify the safety or effectiveness of compounded drugs before they are marketed and dispensed to consumers (FDA, 2017a). While FDA’s role in overseeing compounding has expanded in recent decades, state entities such as state boards of pharmacy are currently the primary regulators of drug compounding practices (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018). In contrast, FDA exercises substantial oversight over other types of prescription products and commercial over-the-counter drugs under the auspices of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), which grants FDA the authority to oversee the safety of food, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics. Since the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the FDCA, manufacturers have been required to demonstrate efficacy as well as safety of new drugs before they can be sold in the United States, thereby protecting the public from ineffective or potentially dangerous products (Kim, 2017).1

Evidence suggests that the use of compounded preparations is substantial and is expected to increase (Ugalmugale, 2018). The minimal federal and state oversight protection for consumers is cause for marked concern

___________________

1 Drug Amendments Act of 1962, Public Law 87-781, 87th Cong., 2nd sess. (October 10, 1962):S 1522.

that an increasing fraction of drugs used in the United States are consumed without assurance of their quality, safety, or effectiveness. Gaps in federal and state-level regulation and oversight need to be addressed to provide confidence in the safe and appropriate use of compounded topical pain creams. Throughout this chapter, the committee will provide a brief overview of current regulations for compounded medication compared to FDA-approved medications, as well as highlighting opportunities to address current gaps in the system.

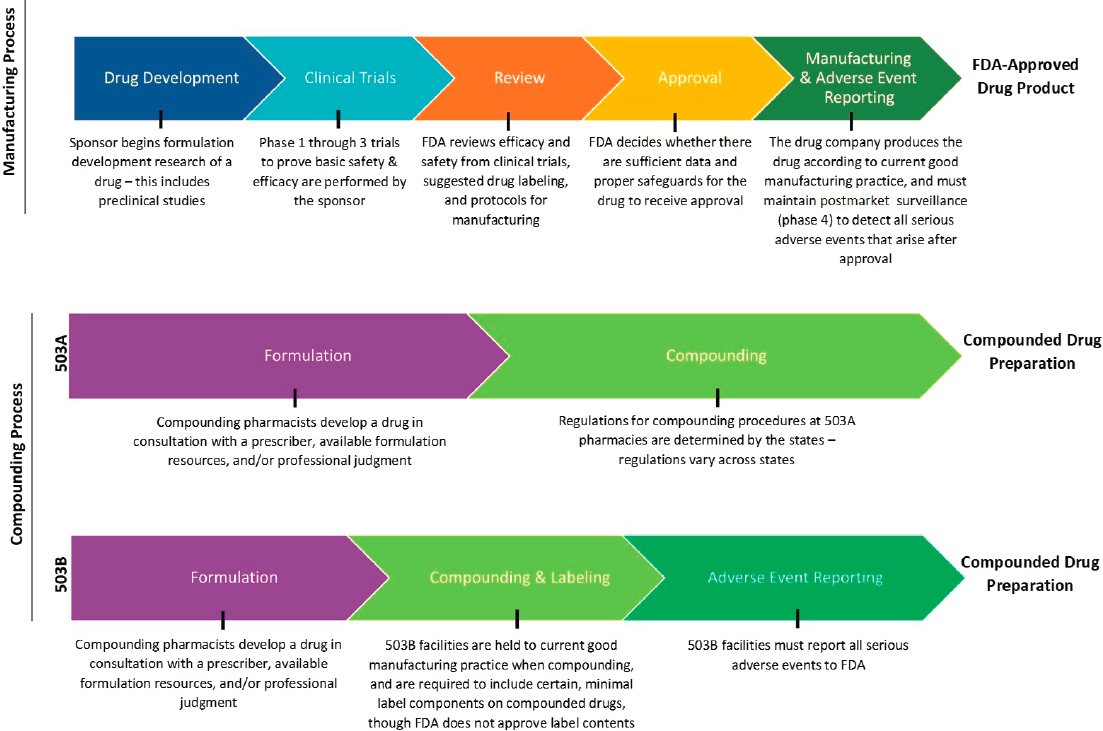

FDA Drug Approval Process for Human Prescription and Human Over-the-Counter Drug Products

FDA’s drug development and approval processes are intended to ensure patients receive safe and effective medications. However, the path from the lab bench to the patient bedside is inherently complex and costly. FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research regulates human prescription and human over-the-counter drugs, and it is responsible for helping to ensure drugs are safe and effective for their intended use in patients (FDA, 2019c). See Figure 4-1 for a visual description of select steps within the drug approval process. The FDCA requires that pharmaceutical companies demonstrate basic safety and efficacy of new drugs before they can be sold in the United States, but most candidate drugs are unable to meet those standards and do not receive approval (Wong et al., 2018). FDA approves a new drug only after careful review of the information on its effects to determine whether the benefits outweigh known and potential risks (FDA, 2019c). The next section provides an overview of the process by which FDA regulates and oversees drug development, approval, and postmarketing surveillance for a typical new drug. FDA also has guidance specific to the approval of products with multiple active ingredients. In these cases, each ingredient’s benefit is typically established with clinical data from studies that compare the fixed-combination drug product to individual component treatment arms (with and without placebo) over multiple doses.2,3

___________________

2 Fixed-combination prescription drugs for humans. 21 CFR § 300.50 (January 5, 1999).

3 FDA regulation for fixed-combination drug products allows for two or more drugs to be combined in a single dosage form when each component makes a contribution to the claimed effects and the dosage of each component (including amount, frequency, and duration) is such that the combination is safe and effective for a significant patient population requiring such concurrent therapy as defined in the drug labeling.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Oversight of Drug Development, Approval, and Postmarketing Surveillance

FDA’s direct involvement begins when the drug sponsor has gathered sufficient preclinical information to warrant clinical testing in humans. The drug sponsor must submit the results of its preclinical testing in an investigational new drug application, which FDA reviews to ensure that research participants will not be exposed to undue risk (FDA, 2016a). FDA regulations describe a multistage process of human clinical testing:

- Phase 1 trials are designed to assess drug metabolism and excretion, and identify the most frequent, acute safety issues (usually tested in a small number of healthy volunteers).

- Phase 2 trials are typically conducted via randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to gather initial data about drug activity and clinical effects in a larger number of individuals who have the condition or disease the product is intended to treat. These trials often evaluate a range of doses to determine the optimal dose for both efficacy and safety.

- Phase 3 trials are intended to provide the primary clinical evidence of safety and efficacy of the drug, typically through RCTs that compare the drug with a placebo or another product approved for the sought indication. These trials may also study different populations, different drug dosages, or the drug in combination with other drugs that are already approved (FDA, 2016a).

Depending on the results of these clinical trials, the drug sponsor—typically a pharmaceutical company—may file a new drug application proposing that FDA approve a new product for sale and marketing in the United States. FDA reviews the information to determine (1) whether the studies demonstrate the drug has substantial evidence of efficacy for the proposed indication, sufficient safety, and benefits that outweigh the risks; (2) appropriateness and content of the proposed package label; and (3) adequacy of the methods used in manufacturing and controls used to maintain the drug’s quality (FDA, 2019d).

Further safety monitoring after FDA approves a drug is critical, because the clinical trials that support approval cannot predict all effects when the drug is used more broadly. Broad use of the drug in patients with other concomitant diseases or patients who are using other medications may lead to adverse events that were not observed in clinical studies. Manufacturers of approved drugs are required to submit regular safety updates to FDA, including results of further studies and individual reports of adverse events from clinicians and the public. FDA’s postmarket surveillance programs also

NOTES: The figure is intended to provide a general overview of the statutory and regulatory processes required of FDA-approved drug products and compounded drug preparations. The figure does not offer a complete summary of the complex regulatory framework for all drug products or compounded preparations. Compounding preparations can be made from either bulk drug substances or FDA-approved products that are subsequently modified. 503B outsourcing facilities can make compounded drugs without a patient-specific prescription.

SOURCE: Original image. Information sources include FDA, 2016a; Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act § 503A and § 503B.

collect reports submitted voluntarily to FDA by health professionals and consumers. FDA also maintains the Sentinel Initiative, a large electronic database of health outcomes derived largely from administrative and claims data from health insurers that can be used to follow up on safety signals identified through postmarket safety reports (FDA, 2016c). Additionally, FDA may require that sponsors monitor the risks and benefits of a drug in phase 4 trials or postmarket surveillance studies and, for certain drug products that carry serious risks, a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy may be required to reduce occurrence or severity of particular serious adverse events (FDA, 2019g).

Regulation and Oversight for Compounded Preparations

Compounded preparations are not subject to the same FDA oversight and approval processes as manufactured prescription drugs or commercial over-the-counter products. However, Congress has clarified the role FDA plays in regulating compounding in recent decades, under provisions of the FDCA.4 Federal law in the United States establishes two categories of compounding, referred to as “503A pharmacy compounding” and “503B outsourcing facilities.” These two categories were created by the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 and the Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013, which added Sections 503A and 503B of the FDCA, respectively. (See Figure 4-1 for a visual description comparing select steps within the statutory and regulatory processes for FDA-approved drugs and compounded preparations.)

503A Compounding Pharmacies and 503B Outsourcing Facilities

The specifics of federal and state regulatory authority over compounding are different for 503A compounding pharmacies versus 503B outsourcing facilities.

503A compounding pharmacies

Compounding pharmacies that qualify for Section 503A exemptions are not required to register with FDA. These pharmacies are allowed to produce compounded preparations upon receipt of a valid patient-specific prescription, or in limited quantities in anticipation of future prescriptions. Compounded preparations made under 503A are exempt from FDA’s requirements for new drug approval, labeling with adequate directions for use, and current good manufacturing practice requirements. To qualify, they are required to meet certain requirements described in Section 503A of the FDCA, including but not limited

___________________

4 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

to (1) being compounded by a licensed pharmacist or licensed physician, (2) being compounded in a state that has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with FDA or within a licensed pharmacy (or by a licensed physician) where the compounded preparations distributed out of state do not exceed 5 percent of total prescriptions dispensed or distributed by that particular pharmacy or physician,5 (3) not using components of drugs removed from the market for being unsafe or ineffective,6 and (4) complying with the prescription requirement mentioned above. Additionally, 503A compounding pharmacies are still required to comply with other applicable requirements in the FDCA, such as the prohibition of insanitary conditions. (See Box 4-1 for an additional discussion on regulations for allowable compounding practices under the FDCA.)

503B outsourcing facilities

These facilities are subject to different requirements than 503A compounding pharmacies, and similarly qualify for different exemptions. If a compounding facility decides it would like to qualify for the exemptions permitted under Section 503B, it must first voluntarily register with FDA as an outsourcing facility. In addition to registering with FDA, outsourcing facilities must comply with all other 503B requirements, including but not limited to (1) producing drugs compounded by or under the direct supervision of a licensed pharmacist, (2) not using components of drugs removed from the market after being found to be unsafe or ineffective, and (3) minimal labeling requirements. Outsourcing facilities are not exempt from current good manufacturing practice requirements. Unlike 503A compounding pharmacies, 503B outsourcing facilities must report adverse events to FDA and are subject to routine FDA inspections on a risk-based schedule. (See Box 4-3 for an additional discussion on adverse event reporting.) Facilities that comply with all of 503B’s requirements qualify for exemption from FDA’s requirements for new drug approval, drug supply-chain security, and labeling with adequate directions for use.7 Importantly, 503B outsourcing facilities are permitted to compound without patient-specific prescriptions and ship prescriptions to clinicians and patients across the United States. Therefore, they tend to be

___________________

5 A standard Memorandum of Understanding has not yet been finalized. A draft form of the agreement, published in 2018, can be found at https://www.fda.gov/media/91085/download (accessed April 13, 2020).

6 A list of drugs that have been removed from the market for reasons of safety or effectiveness can be found online. See Drug products withdrawn or removed from the market for reasons of safety or effectiveness. 21 CFR 216.24 (December 11, 2018).

7 503B facilities must include labeling information such as drug name, dosage form, and strength, and a statement that the drug is compounded; however, these requirements do not meet the current labeling standards for FDA-approved products. In addition, FDA does not review the contents of compounded drug labels (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016b).

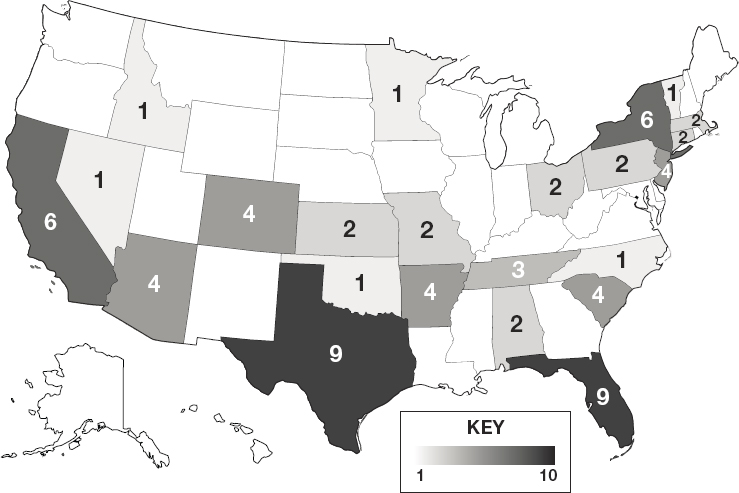

NOTES: Darker shading reflects a greater number of 503B outsourcing facilities in the state. See Appendix E for additional data on 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities.

SOURCE: FDA, 2019e.

larger operations that produce sizable quantities of compounded preparations (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016b). Figure 4-2 depicts the geographic distribution of 503B outsourcing facilities across the nation.8

Sections 503A and 503B also place limits on the bulk drug substances (i.e., active pharmaceutical ingredients) that these pharmacies can use in compounding drug preparations (FDA, 2019a,b). Section 503A pharmacies may only use bulk drug substances that (1) comply with an applicable United States Pharmacopeia (USP) or National Formulary (NF) monograph and the USP chapter on pharmacy compounding, (2) are components of FDA-approved drug products if an applicable USP or NF monograph does not exist, or (3) appear on FDA’s list of bulk drug substances that can be used in compounding. By contrast, 503B facilities may only use bulk drug substances that (1) are used to compound drug products that appear on FDA’s drug shortage

___________________

8 Values of 503A pharmacies are difficult to estimate due to a lack of standardized reporting, wide-ranging scopes of compounding between pharmacies, and frequent changes in the number of 503A compounding pharmacies.

list at the time of compounding, distribution, and dispensing, or (2) appear on FDA’s list of bulk drug substances for which there is a clinical need.

As stated above, both 503A and 503B permit the use of bulk drug substances that appear on lists developed by FDA, but these lists are just one of the potential sources from which individuals who compound may select bulk drug substances. FDA is in the process of compiling 503A and 503B “bulk lists” of allowable bulk drug substances for compounding. Anyone with sufficient information can nominate bulk drug substances to the lists and anyone may challenge the nomination of a bulk drug substance to either list during a notice-and-comment period. However, until the lists are finalized, FDA’s interim policy authorizes facilities to compound any bulk drug substance that has been nominated to the lists with sufficient information for FDA to evaluate the substance in the future, except when FDA has identified significant safety risks related to the use of the substance in compounding (FDA, 2017b,c).9

United States Pharmacopeia Standards

The U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention is a nonprofit organization committed to ensuring the quality of compounded medicines by setting public standards for identity, strength, quality, and purity, including those used in compounded preparations. Specifically, there are three types of standards for compounding10:

- USP-NF monographs for bulk drug substances and other ingredients that may be used in compounded preparations set standards for identity, quality, purity, strength, packaging, and labeling.11

- USP-compounded preparation monographs provide guidance and set quality standards for preparing a limited number of compounded formulations.12 These monographs include formulas, directions for compounding, beyond-use dates, packaging and storage information, acceptable pH ranges, and stability-indicating assays.

___________________

9 This text has changed since the prepublication release of this report to clarify that compounders cannot use bulk substances nominated to the lists if FDA is aware of significant safety risks.

10 Although drugs in the USP-NF must adhere to USP standards, this requirement does not differentiate between commercially manufactured products and compounded prescription medicines.

11 The FDCA describes which bulk drug substances may be used in compounding. It states that compounders may use bulk drug substances that have a USP-NF monograph, and that these bulk drug substances must comply with the standards set forth in the corresponding USP-NF monograph and the USP chapter on pharmacy compounding. See Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

12 At the time of this report, USP currently provides more than 175 compounded preparation monographs.

- Eight essential General Chapters provide overviews of relevant information, procedures, and analytical methods for compounding (see Box 4-2).

USP itself does not have regulatory or enforcement authority, but USP standards are enforceable under federal law in the FDCA, and some state regulations have also incorporated references to USP standards. USP standards for compounding were first included in the federal law in Section 503A of the FDCA.

State-Level Regulation and Oversight

As described in this chapter, while FDA provides some regulations for compounding preparations, state boards of pharmacy retain primary responsibility for the regulation and oversight of 503A compounding pharmacies. Both the frequency and content of state board of pharmacy inspections vary greatly by state. State-level oversight usually involves a site inspection, which may include a review of compounding procedures, facilities, equipment, staff training, quality assurance, and documentation, among other aspects (Dowell, 2019). Important to the document review are standard operating procedures that detail facility activities and maintenance, personnel, compounding equipment and preparation, and tests to be performed on finished preparations (Allen, 2012; USP, 2017). Violations may result in warning letters, product seizures, injunctions, or prosecution by state authorities, and violators may be referred to FDA.

Voluntary Accreditation

Compounding pharmacies can undergo a voluntary accreditation process to gain third-party validation and (potentially) a competitive edge in the marketplace. For instance, the Accreditation Commission for Health Care’s Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board has developed national standards for compounding pharmacies based on the consensus of industry experts (Springer, 2013). This accreditation evaluates compliance with the nonsterile and sterile pharmacy compounding processes defined by USP <795> and USP <797> for improved quality and safety. Similarly, the Joint Commission Medication Compounding certification program assesses a pharmacy’s compliance with specific standards for preparation and dispensing of sterile and unsterile products in accordance with USP <795> and <797> (Joint Commission, 2019). Starting in fall 2019, the Board of Specialty Pharmacies began offering an exam for pharmacists to become accredited in compounded sterile preparations, though the specialty has yet to receive accreditation from the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (Board of Pharmacy Specialties, 2020).

GAPS IN FEDERAL AND STATE REGULATION AND OVERSIGHT FOR COMPOUNDED PREPARATIONS

As the compounding market adjusts to its continuously evolving regulatory ecosystem, new sets of gaps and challenges are emerging at the federal and state levels. Gaps in the regulation and oversight of compounding pharmacies and outsourcing facilities need to be addressed to mitigate the potential safety risks and concerns related to the effectiveness of the compounded preparations. These gaps include

- Variable inspections of compounding pharmacies and outsourcing facilities,

- State-level variability in the oversight of compounding,

- Insufficient labeling requirements, and

- Insufficient data collection and surveillance of dispensed compounded preparations (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016b).

Insufficient Regulation and Oversight of Compounding Pharmacies and Outsourcing Facilities

Insufficient Inspections of Pharmacies and Facilities

FDA neither routinely inspects compounding pharmacies nor assesses the quality of the compounded preparations produced by those pharmacies (Gudeman et al., 2013). Therefore, unlike FDA-approved products, compounded preparations are not necessarily produced using validated processes or properly calibrated and cleaned equipment (Gudeman et al., 2013). The shelf life of a sterile compounded preparation may not have been verified by stability testing to ensure that it retains its original strength and purity over time (Gudeman et al., 2013). Insanitary conditions have been reported in a number of compounding pharmacies, which can lead to drug contamination with bacteria, fungus, or virus (USP, 2017). Even if a certificate of analysis for a drug substance is provided, there may be questions regarding whether follow-up testing was carried out. For example, a study conducted in 2001 by FDA found that up to one-third of a small sample of compounded preparations failed quality testing (FDA, 2018). Between 2006 and 2009, the Missouri Board of Pharmacy found quality failures in 11–25 percent of the compounded preparations it evaluated; drug potency ranged from 0 percent to 450 percent (Missouri Board of Pharmacy, 2009).

In general, the evidence suggests that certain compounded preparations may not be prepared in accordance with safe and appropriate compounding practices, and quality assurance of those compounds may not be sufficient. Patient safety issues associated with poor drug quality include inadequate

therapy, adverse events, antimicrobial resistance, and health care–associated infections (USP, 2017).

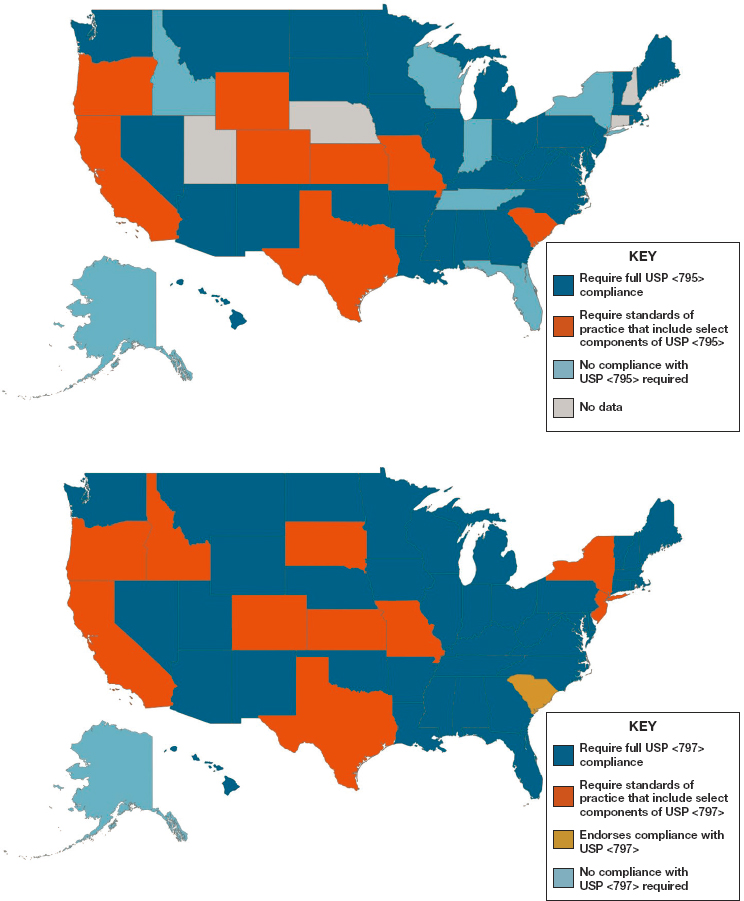

State-to-State Variability in State-Level Regulation and Oversight

Although most compounding is patient specific and under state jurisdiction, regulation and oversight of compounding practices are widely variable state by state (GAO, 2016). For example, recent data from the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy13 suggest that greater than 30 percent of states do not require full compliance with compounding standards issued by USP for either nonsterile or sterile compounding (NABP, 2018). See Figure 4-3 to review state-by-state variation in required compliance with USP standards.

Furthermore, compounding performed in licensed physicians’ offices is not regulated in the same way as 503A compounding pharmacies—in most states, there is no oversight of this practice by state boards of medicine or pharmacy (NABP, 2017; The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016a). Moreover, the scope of physician compounding is poorly understood and not well quantified (NABP, 2017). Similarly, the extent to which hospitals carry out large-scale in-house compounding is not sufficiently quantified or regulated (Myers, 2013).

Oversight mechanisms may be unclear to state regulators (GAO, 2016), and the resources for appropriately rigorous state-level oversight are often unavailable (Glassgold, 2013). In 2014, The Pew Charitable Trusts convened an advisory committee to establish best practices to support state oversight, which recommended eight best practices (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016a). A few years later it published an update on states’ progress that targeted these three best practices:

- Applying USP quality standards for sterile compounding,

- Harmonizing with federal law on compounding without prescriptions, and

- Carrying out annual inspections of sterile compounding facilities (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).

A 2018 Pew review found that most states conform with the first two best practices, but that state inspections of 503A sterile compounding have declined, which is likely caused by a lack of resources and capacity (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).14

___________________

13 The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is a nonprofit professional membership association for state boards of pharmacy.

14 In an attempt to promote consistency in pharmacy inspections across states, NAPB has recently developed a Multistate Pharmacy Inspection Blueprint Program (NABP, 2019).

NOTES: Maps are based on survey data reported by state boards of pharmacy and collected by the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, as well as updates from state boards that had pending legislation at the time of data collection (Idaho Administrative Code, Section 27.01.05.100.05; Illinois Administrative Code, Section 1330.640; Code of Maryland Regulations, Section 10.34.19.02; Pennsylvania Code, Section 49.27.601).

SOURCE: The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018.

Variability in compounding quality standards enforced from state to state is only one piece of the puzzle. States also differ in the quality standards they apply to out-of-state pharmacies that ship drugs into their state. Some states require that out-of-state pharmacies follow the regulations of the state into which the compounded preparations are shipped, while others enforce those of the state where the drug is compounded. A consequence is that compounded formulations made in states with less rigorous quality standards can find their way into the hands of a patient that lives in a state that enforces the compounding quality standards outlined in USP <795> and <797> (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).

Insufficient Labeling Requirements

Federal requirements for 503A compounding pharmacies are relatively lax compared with 503B outsourcing facilities. For example, compounded preparations from 503A compounding pharmacies are not dispensed with standardized product inserts that outline instructions for use, known side effects, or safety warnings, even if such warnings are required for similar FDA-approved manufactured drug products. Although certain compounding pharmacies may dispense written information with compounded preparations, there is no regulation to require standardization of this practice between pharmacies or even within states. As such, patients are likely receiving variable information regarding what is in their preparation (i.e., active ingredients, inactive ingredients), how to use the preparation, or potential adverse reactions. See Chapter 7 for an additional discussion on the effect of insufficient labeling on patients’ misuse of compounded topical pain creams.

Insufficient Data Collection and Surveillance

The committee encountered difficulty in securing publicly available, accurate data on the use, safety, and effectiveness of compounded preparations in general, and of compounded topical pain creams in particular. It is likely that multiple barriers to data collection contribute to this dearth of evidence (Glassgold, 2013; McPherson et al., 2019), including

- Lack of a locus for centralized data collection;

- Lack of federal reporting requirements; and

- Variable insurance coverage for a broad range of compounded medications.

Additional complicating factors are the amount of variance in state-level oversight and in the procedures used between and within compounding pharmacies across the nation (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018). Even if records of formulations, prescribing practices, and patient use are kept, they are generally not standardized and therefore are not conducive to drawing specific research conclusions. Potential data on the use of compounded topical pain creams that could be collected in a standardized format include

- the number, weight, or volume of units prepared;

- commonly compounded formulations of topical pain creams;

- the number of prescriptions compounded;

- the cost or value of each unit; and

- the number of patients who receive prescriptions.

Although the concept of the length of treatment per single prescription may be nebulous across pharmacies, how it is defined in practice—for example, as a week or month(s) supply—is also a critical data point to collect.

In addition, as discussed in sections above, it is often difficult to assess potential adverse effects or events related to the use or misuse of compounded preparations because they are not subject to postmarketing surveillance as required of FDA-approved products. 503A compounding pharmacies are not required to collect or share adverse event data with FDA; without these data, it is difficult to accurately characterize the public health aspects of compounded medications. See Box 4-3 for an additional discussion on adverse event reporting. Owing to the substantial growth in demand for compounded preparations, regulatory gaps remain a high-priority concern.

___________________

15 This text has changed since the prepublication release of this report. As described in the chapter, 503B compounding facilities are required to submit serious adverse events to FDA.

Need for a Balanced Approach to Regulatory Expansion

Owing in part to the lack of stringent regulatory oversight, poor-quality compounded drugs have been associated with multiple outbreaks of infections and deaths over the past decades, although the number of people who have been harmed by compounded drugs remains unknown (Glassgold, 2013). In the aftermath of the New England Compounding Center meningitis outbreak of 2012, 753 people became ill and 64 people died after receiving contaminated steroid injections (CDC, 2015). That disaster was highly publicized, but there have been other adverse events in recent years that resulted in patient injuries and deaths (Staes et al., 2013) (see Chapter 7 and Appendix F for a discussion of adverse events associated with the use of compounded topical pain creams). These events have prompted Congress to clarify FDA’s regulatory authority over compounding with the passage of the Drug Quality and Security Act in 2013 (Woodcock and Dohm, 2017). Since 2013, FDA has issued multiple guidances pursuant to compounding as well as compounding priorities that describe FDA’s plans to further reduce the risks of compounded preparations (FDA, 2019f; Gottlieb, 2018; Gottlieb and Abram, 2019) (see Box 4-4 for a brief summary of FDA’s Compounding Priorities).

Although there are concerns that the practice of compounding has “effectively outgrown the laws designed to regulate it” (Shepherd, 2018), regulatory efforts can continue to strive to balance safety and effectiveness for the clinical populations that need access to compounded therapies. These two strands are not in opposition to each other; rather, efforts can

be made to accomplish them in tandem. FDA has stated that it seeks to strike such a balance between preserving access to lawfully marketed compounded drugs for patients who have a clinical need for them while protecting patients from the risks associated with compounded drugs that are not produced in accordance with the applicable requirements of federal law (FDA, 2017a). The safety of the individual ingredients, ingredient interactions, and absorption by the body need to be regulated by evidence-based guidelines. This would help to ensure that the components of compounded medications are safe and effective, while still maintaining pharmacists’ abilities to customize the compounds.

REFERENCES

Allen, L. V. J. 2012. The art, science, and technology of pharmaceutical compounding, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association.

Board of Pharmacy Specialties. 2020. Accreditation. https://www.bpsweb.org/about-bps/accreditation (accessed April 8, 2020).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. Multistate outbreak of fungal meningitis and other infections—Case count. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/outbreaks/meningitis-map-large.html (accessed April 8, 2020).

Dowell, M. 2019. Compliance tips on how to pass state board of pharmacy inspections. Journal of Health Care Compliance 21(5).

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2013. Guidance for industry: Labeling for human prescription drug and biological products—Implementing the PLR content and format requirements. https://www.fda.gov/media/71836/download (accessed April 9, 2020).

FDA. 2015. Adverse event reporting for outsourcing facilities under section 503b of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/90997/download (accessed April 9, 2020).

FDA. 2016a. FDA drug approval process infographic (horizontal). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-information-consumers/fda-drug-approval-process-infographic-horizontal (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2016c. Postmarketing surveillance programs. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/postmarketing-surveillance-programs (accessed January 30, 2020).

FDA. 2017a. FDA’s human drug compounding progress report: Three years after enactment of the Drug Quality and Security Act. https://www.fda.gov/media/102493/download (accessed January 15, 2020).

FDA. 2017b. Interim policy on compounding using bulk drug substances under section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/interim-policy-compounding-using-bulk-drug-substances-under-section-503a-federal-food-drug-and (accessed January 30, 2020).

FDA. 2017c. Interim policy on compounding using bulk drug substances under section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/interim-policy-compounding-using-bulk-drug-substances-under-section-503b-federal-food-drug-and (accessed January 30, 2020).

FDA. 2018. Report: Limited FDA survey of compounded drug products. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/report-limited-fda-survey-compounded-drug-products (accessed January 30, 2020).

FDA. 2019a. Bulk drug substances used in compounding under section 503A of the FD&C Act. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/bulk-drug-substances-used-compounding-under-section-503a-fdc-act (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2019b. Bulk drug substances used in compounding under section 503B of the FD&C Act. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/bulk-drug-substances-used-compounding-under-section-503b-fdc-act (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2019c. CDER: The consumer watchdog for safe and effective drugs. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-information-consumers/cder-consumer-watchdog-safe-and-effective-drugs (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2019d. New drug application (NDA). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/types-applications/new-drug-application-nda (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2019e. Registered outsourcing facilities. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/registered-outsourcing-facilities (accessed October 31, 2019).

FDA. 2019f. Regulatory policy information (human drug compounding). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/regulatory-policy-information (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2019g. Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies REMS. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems (accessed April 8, 2020).

FDA. 2020. Postmarketing adverse event reporting compliance program. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/postmarketing-adverse-event-reporting-compliance-program (accessed March 25, 2020).

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2016. Drug compounding: FDA has taken steps to implement compounding law, but some states and stakeholders reported challenges. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681096.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020).

Glassgold, J. M. 2013. Congressional Research Service: Compounded drugs. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43082.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020).

Gottlieb, S. 2018. 2018 compounding policy priorities plan. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/2018-compounding-policy-priorities-plan (accessed April 8, 2020).

Gottlieb, S., and A. Abram. 2019. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D. and Deputy Commissioner Anna Abram on new 2019 efforts to improve the quality of compounded drugs. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statementfda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-and-deputy-commissioner-anna-abram-new-2019-efforts (accessed April 8, 2020).

Gudeman, J., M. Jozwiakowski, J. Chollet, and M. Randell. 2013. Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs in R&D 13(1):1–8.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2000. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Joint Commission. 2019. Medication compounding certification. https://www.jointcommission.org/certification/medication_compounding.aspx (accessed January 30, 2020).

Kesselheim, A. S., M. S. Sinha, P. Rausch, Z. Lu, F. A. Tessema, B. M. Lappin, E. H. Zhou, G. J. Dal Pan, L. Zwanziger, A. Ramanadham, A. Loughlin, C. Enger, J. Avorn, and E. G. Campbell. 2019. Patients’ knowledge of key messaging in drug safety communications for Zolpidem and Eszopiclone: A national survey. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 47(3):430–441.

Kim, S. H. 2017. The Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013: Compounding consistently. Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 19(2). https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jhclp/vol19/iss2/5 (accessed January 16, 2020).

McPherson, T., P. Fontane, and R. Bilger. 2019. Patient experiences with compounded medications. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 59(5):670–677.

Missouri Board of Pharmacy. 2009. Compounding report. https://pr.mo.gov/pharmacists-compounding.asp (accessed April 8, 2020).

Myers, C. E. 2013. History of sterile compounding in U.S. hospitals: Learning from the tragic lessons of the past. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 70(16):1414–1427.

NABP (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy). 2017. National reports raise questions about oversight of drug compounding in physicians’ offices. Innovations 46(3):6–8.

NABP. 2018. Survey of pharmacy law—2019. Mount Prospect, IL: NABP.

NABP. 2019. Multistate pharmacy inspection blueprint program. https://nabp.pharmacy/member-services/inspection-tools-services/multistate-pharmacy-inspection-blueprint-program (accessed December 23, 2019).

Pappa, D., and L. K. Stergioulas. 2019. Harnessing social media data for pharmacovigilance: A review of current state of the art, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 8:113–135.

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2016a. Best practices for state oversight of drug compounding. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2016/02/best_practices_for-state_oversight_of_drug_compounding.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2016b. National assessment of state oversight of sterile drug compounding. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2016/02/national_assessment_of_state_oversight_of_sterile_drug_compounding.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020).

The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP. 2018. State oversight of drug compounding: Major progress since 2015, but opportunities remain to better protect patients. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/02/drug_safety_assesment_web.pdf (accessed January 15, 2020).

Shepherd, J. 2018. Regulatory gaps in drug compounding: Implications for patient safety, innovation, and fraud. DePaul Law Review 68(2):12. https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol68/iss2/12 (accessed January 30, 2020).

Springer, R. 2013. Compounding pharmacies: Friend or foe. Plastic Surgical Nursing 33(1):24–28.

Staes, C., J. Jacobs, J. Mayer, and J. Allen. 2013. Description of outbreaks of health-care-associated infections related to compounding pharmacies, 2000–12. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 70(15):1301–1312.

Ugalmugale, S. 2018. U.S. compounding pharmacies market. https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/us-compounding-pharmacies-market (accessed January 15, 2020).

USP (United States Pharmacopeia). 2017. Ensuring patient safety in compounding medicines. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/about/public-policy/safety-in-compounding-of-medicines-policy-position.pdf (accessed January 30, 2020).

USP. n.d. USP compounding standards. https://www.usp.org/compounding-standards-overview (accessed January 30, 2020).

Ventola, C. L. 2018. Big data and pharmacovigilance: Data mining for adverse drug events and interactions. Physical Therapy 43(6):340–351.

Wong, C. H., K. W. Siah, and A. W. Lo. 2018. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics 20(2):273–286.

Woodcock, J., and J. Dohm. 2017. Toward better-quality compounded drugs—An update from the FDA. New England Journal of Medicine 377(26):2509–2512.

This page intentionally left blank.