Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

Behavioral health and substance use disorders (SUDs) affect approximately 20 percent of the U.S. population (NIMH, 2017). Of those with an SUD, approximately 60 percent also have a mental health disorder (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2015). Together, these disorders account for a substantial burden of disability, have been associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality from other chronic illnesses, and can be risk factors for incarceration, homelessness, and death by suicide. In addition, they can compromise a person’s ability to seek out and afford health care and adhere to treatment recommendations (Roberts et al., 2015; WHO, 2015).

Despite the high rates of comorbidity of physical and behavioral health conditions (which include mental health and substance-related and addictive disorders) integrating services for these conditions into the American health care system has proved challenging. Part of the explanation lies in a historical legacy of discrimination and stigma that made people reluctant to seek help and also led to segregated and inhumane services for those suffering from mental health or substance use disorders (Storholm et al., 2017). Health

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

insurance programs also often provided limited coverage of services for these disorders compared to services for other conditions (Storholm et al., 2017).

Individuals with mental health conditions face numerous barriers to receiving quality care: in 2018, only 43.3 percent of U.S. adults with mental illness received treatment (NAMI, 2019). Research has found that the most common reason for not seeking care is an inability to pay for services (Novak et al., 2019). In addition, fear of discrimination in housing, employment, military service, and other arenas can deter people from seeking or continuing care (Mojtabai et al., 2014). Nearly 90 million Americans live in areas with a shortage of mental health professionals, a situation exacerbated by a lack of adequate training (AAPA, 2016). Additionally, many professionals do not have the support to identify mental health and substance use disorders (MHSUDs) and then appropriately manage care through direct services, referral, and collaboration (AAPA, 2016). Often, evidence-based psychosocial interventions are not available as a part of routine clinical care due to issues related to access to quality care, workforce training, insurance coverage, or fragmentation of care (Priester et al., 2016).

To provide a structured environment and neutral venue to discuss data, policies, practices, and systems that affect the diagnosis and provision of care for MHSUDs, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) created the Forum on Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. The forum activities are expected to advance the discussion and generate potential ideas on ways to address many of the most persistent problems in delivering mental health and substance use services. The inaugural workshop, held October 15–16, 2019, in Washington, DC, explored the key policy challenges and opportunities that impede efforts to improve care for those individuals with MHSUDs.

The first session set the stage for the ensuing discussions by acknowledging the critical importance of person-centered care, shared decision making, and patient and family engagement in treating MHSUDs. The second session focused on identifying essential components of care for people with MHSUDs. During lunch, participants engaged in group discussions on the topics of the first two sessions. Building on those discussions, the third session examined opportunities to translate knowledge into practice and monitor implementation of evidence-based practices. The workshop’s first day concluded with a brief summary of the luncheon discussions and lessons learned and key messages from the session presentations.

The second day began with a session exploring ways in which data can be leveraged to improve care delivery and patient outcomes for people with MHSUDs. The final session examined the challenges and opportunities related to developing the workforce to provide high-quality care for MHSUDs. Each

of the five sessions included a discussion period in which audience participants could pose questions to the speakers.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions. A broad range of views was presented. Box 1 provides a summary of suggestions for potential actions from individual workshop participants. The workshop agenda and Statement of Task are in Appendixes A and B, respectively. The speakers’ presentations (as a PDF and video files) are archived online.2

PROMOTING PERSON-CENTERED CARE, SHARED DECISION MAKING, AND PATIENT AND FAMILY ENGAGEMENT

The workshop opened with Michael Weaver, the executive director of the International Association of Peer Supporters, welcoming the workshop participants. Weaver explained that the first session would set the stage by focusing on the importance of promoting person-centered care, patient and family engagement, and shared decision making.

Flipping the Script: Advancing Patient-Centered Care and Supported Decision Making

Keris Jän Myrick, the chief of peer services at the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, began the session by pointing out that the focus of mental health care tends to be on the mental illness and reducing symptoms, rather than the various aspects of patients’ lives that those symptoms disrupt. What would happen, she asked, if that script was flipped and mental health care was delivered in the context of wellness, well-being, and an individual’s meaningful roles in life rather than using illness as the care model target? Myrick encountered one example of that flipped script in Trieste, Italy, where mental health centers are open 24 hours per day and the emphasis is on keeping people connected with their community, family, friends, social activities, and meaning and purpose (Mezzina, 2014). “All of these things they are able to carry out because of their deep investment in their values and principles,” she said.

Those values and principles translate into warmly welcoming everyone who comes through the doors of the mental health center and “meeting people where they are” with regard to their mental health status. The health centers’ care model focuses on inclusion, participation in the community, and helping

___________________

2 For additional information, see http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/MentalHealth/MentalHealthSubstanceUseDisorderForum/2019-OCT-15.aspx (accessed January 14, 2020).

people to stay in their homes even when they are in crisis. Staff, she noted, work hard at building resilience in the context of relationship, community, and meaning and purpose in life.

Myrick added that an important aspect of “flipping the script” is to tap into the power of peer support for both individuals receiving care and their parents, family, and other caregivers. Myrick noted that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has produced several briefs that discuss peer support as part of mental health and substance use care.3 She also pointed out that the National Alliance on Mental Illness

___________________

3 SAMHSA’s peer support briefs are available at https://www.samhsa.gov/brss-tacs/recovery-support-tools/peers (accessed November 1, 2019).

(NAMI) has created a guidebook for mental health caregivers to help them understand what they can do on their own and who in the mental health care system should provide specific aspects of care.4

Returning to the earlier example of the health center in Trieste, Myrick explained that mental health and substance use care relies on supported decision making, in contrast to shared decision making, with the individuals seeking care identifying the supporters who will help them in their decision making. This approach to care maximizes an individual’s autonomy, explained Myrick. She noted that the American Bar Association developed a guide to help individuals, families, and lawyers determine how to best provide supported decision making. The PRACTICAL Toolkit (ABA, 2016) states the following:

- Presume guardianship is not needed

- Reason: Clearly identify the reasons for concern

- Ask if a triggering concern may be caused by temporary or reversible conditions

- Community: Determine if concerns can be addressed by connecting the person to family or community resources

- Team: Ask the person if they already have a team to help make decisions

- Identify abilities: Identify areas of strengths and limitations in decision making

- Challenges: Screen for and address any potential challenges presented by supporters

- Appoint a legal supporter or surrogate consistent with the person’s values and preferences

- Limit any guardianship petition or order to only what is necessary

In addition, Temple University’s Collaborative on Community Inclusion developed tools to help people think about self-directed care, which is another way to increase autonomy. “The more one feels empowered and in charge of their care or their support or whatever their needs are in their life, the more able they are to be fully engaged in the community,” said Myrick. She noted that self-directed care is starting to make inroads in mental health care in the United States, though she was not sure if the same was true for substance use care. In Myrick’s opinion, this allows us to examine how we fund care and do so in a way that maximizes people’s autonomy.

___________________

4 The NAMI guidebook is available at https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/Publications-Reports/Guides/Circle-of-Care-Guidebook/CircleOfCareReport.pdf?utm_source=direct&utm_campaign=circleofcare (accessed November 1, 2019).

In closing, Myrick said that flipping the script and truly innovating will require doing things differently, which will include thinking about how to provide care from a humanistic view and considering the values, culture, language, and principles of the individual needing care.

Trauma-Informed Care and the Ryan White Model of Delivery

Building on the opening discussion of supportive care, Edward Machtinger, the director of the Center to Advance Trauma-Informed Health Care and Women’s HIV Program at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), explained that trauma-informed health care5 is a powerful and essential tool to effectively address MHSUDs. “Understanding the impact of trauma on health demystifies why so many patients struggle with substance use and mental illness in the first place and why these conditions are often so refractory to supposedly effective therapies. This understanding explains why some patients can seem chaotic, defensive, or demanding,” he added. Understanding the impact of trauma can also explain why the experiences of health care providers and systems of care can often mirror patients’ trauma experiences.

Trauma-informed care, explained Machtinger, has three tenets. The first tenet states that the occurrence of substance use and mental illness correlates strongly with individual, family, and community-level trauma. Trauma is defined as an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that are experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that have lasting adverse effects. The impact of trauma on adult health and well-being, he noted, is well documented and startling. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study,6 for example, found that high rates of ACEs were strong predictors in a dose-dependent manner of the major causes of adult morbidity, mortality, and disability (Felitti et al., 1998). Individuals who reported four or more ACE categories had 1.6 times the rate of obesity compared to those with no ACEs, as well as more than 2 times the rate of smoking, 3 times the rate of depression, 6 times the rate of attempting suicide, 7 times the rate of alcoholism, and 10 times the rate of intravenous drug use (Felitti et al., 1998). Similarly, adult trauma and the consequences of trauma, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), have also been shown to have dose-dependent relationships with many of the same conditions. The Philadelphia Urban ACE study looked at the additive impact of community-level traumas by assessing the impact of five types of community-level adverse

___________________

5 For more information, see https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org (accessed February 7, 2020).

6 For more information, see https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(98)00017-8/abstract (accessed December 2, 2019).

events, such as experiencing racism, experiencing bullying, witnessing violence, being in foster care, and living in an unsafe neighborhood (Cronholm et al., 2015; Wade et al., 2016). Individuals who experienced three or more of these community-level traumas in childhood were more than twice as likely as those with no community-level ACEs to smoke as an adult and to be depressed, three times more likely to have a substance use problem, and four times as likely to have a sexually transmitted disease. ACEs are not the sole driver of substance use and mental illness; “nonetheless, to understand and effectively treat substance use disorder and mental illness, I have found it incredibly helpful to see these conditions, like HIV, as primarily a symptom of a much larger and more insidious reality of individual, family, and community-level trauma,” said Machtinger.

Machtinger explained that the second tenet of trauma-informed health care is that while trauma makes people more vulnerable to substance use and mental illness, it also acts as an obstacle to effective treatment of those same conditions. The evidence for this tenet is strongest in co-occurring SUD and PTSD, which is associated with poorer recruitment and retention in treatment programs, treatment outcomes, and treatment adherence, and shorter periods of abstinence post-treatment compared to SUD alone (Roberts et al., 2015).

The third tenet is that clinics and environments of care often mirror the trauma experienced by patients. For example, staff and health care providers often feel overwhelmed and unsupported, and as a result, they can sometimes be dismissive and rigid with patients. In turn, patients who have a history of being coerced by an intimate partner or experiencing discrimination or incarceration often feel unwelcome or unsafe in such situations, said Machtinger. “In this way, our clinics can actually be trauma-inducing for patients, pushing them away from the care that they so desperately need,” said Machtinger. These trauma-inducing environments can also contribute to burnout among staff and health care providers, many of whom have histories of trauma themselves. “For us to sustain a movement of healing for substance use disorder and mental illness, we have to take this burnout seriously and adopt trauma-informed practices that support team-based care, reflective supervision, and self-care,” he noted.

Ultimately, understanding the impact of trauma on health and behavior helps health care clinicians be more patient and compassionate and enables them to form trusting connections with patients that are foundational for effective care of people with MHSUDs. “It is from that foundation of a trusting connection that we can provide or link patients to the care that they want and need,” said Machtinger. To be successful in helping individuals with MHSUDs, Machtinger stressed that there needs to be a delivery platform for trauma-informed care that facilitates integrated, interdisciplinary primary and behavioral health care, as well as partnerships with peers and community organizations that support self-care and access to specialty care.

According to Machtinger, the national Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program,7 administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), has been uniquely effective at creating exactly that type of platform for delivering care to individuals with HIV/AIDS. “It is a model that we should all know about and build upon to be successful in overcoming our country’s opioid epidemic and to effectively address other forms of substance use disorder and mental illness,” he said. Machtinger encouraged the use of examples of effective care to guide the development of care delivery approaches for people with MHSUDs. He cautioned that not doing so risks setting the bar for success too low and thus adapting to a health care system that is profoundly insufficient for the needs of patients.

As an example of what effective care can look like in the context of MHSUDs, Machtinger told the story of Pebbles, a 42-year-old woman who had recently entered a residential treatment program for heroin and crack cocaine use and been referred to the UCSF clinic for primary medical care (see Box 2).

Machtinger said the reason he and the clinic staff were able to deliver what was ultimately effective care comes down to three components: (1) the values that guide the clinic staff, (2) provider-level interventions over which staff have some control, and (3) systems-level interventions that required structural change (see Table 1).

The values that informed Pebbles’s care—and that enabled her to stay engaged despite her shame for her drug use and endangering her grandchild—are aligned with the six core values of trauma-informed care, which begins with safety. “She did not think we were going to punish her or stop loving her because of her behavior,” said Machtinger. The next value, trustworthiness and transparency, allowed her to share her feelings and fears. The value of collaboration minimized power differentials between her and clinic staff. Peer support was provided by individuals with shared experiences and she was empowered to recognize her inner strength and resiliency. Lastly, clinic staff had been trained in the value of cultural humility and responsiveness to implicit biases and the realities of historical and intergenerational trauma.

Machtinger explained how UCSF has gone through a deliberate 2-year process to become a trauma-informed clinic. He noted that in terms of clinician-level interventions, “all of our staff and providers understand the impact of trauma on health and behavior.” In addition, all health care providers must be waiver eligible to prescribe buprenorphine and understand that it is imperative to screen for other co-occurring SUDs and mental health conditions. Staff also received training to employ motivational interviewing to help patients achieve their individual goals.

___________________

7 Additional information is available at https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program (accessed November 8, 2019).

TABLE 1 The Characteristics of Effective Trauma-Informed Care

| Values | Provider-Level Interventions | Systems-Level Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Understand impact of trauma on health | Interdisciplinary team-based care |

| Trustworthiness and transparency | See most substance use as self-medication | Peers and community/peer organizations integrated into care |

| Collaboration | Compassion, patient | 30–45-minute visit lengths; long-term relationships |

| Peer support | Prescribe buprenorphine | Integrated behavioral health services (e.g., groups, medication-assisted treatment) |

| Empowerment | Screen and refer for other addictions and mental illness | Partner agencies in community |

| Cultural humility and responsiveness | Motivational interviewing | Leadership support and funding for comprehensive care |

SOURCE: As presented by Edward Machtinger, October 15, 2019.

In terms of systems-level interventions, one crucial factor in the clinic’s success with individuals like Pebbles is that it exists within the larger Ryan White HIV/AIDS care system, Machtinger explained. That system requires and funds the clinic to provide interdisciplinary team-based care that allowed Machtinger, along with the clinic’s social worker, therapist, and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) counselor, to provide care to Pebbles. Other systems-level interventions include

- integrating peers and community/peer organizations into care;

- enabling longer clinic visits and long-term relationships that facilitate trust;

- integrating behavioral health services, including a MAT program and group therapy for trauma and substance use, into primary care;

- establishing partnerships with community-informed residential treatment centers; and

- providing leadership and funding to facilitate this model of care.

Machtinger credits SAMHSA with taking the lead on trauma-informed care nationally and shared that he finds it inspirational that a federal agency can drive an entirely new field. SAMHSA has developed practical guidance for trauma-informed health care in terms of “four Rs,” which states that trauma-informed care

- Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands effective paths for recovery;

- Recognizes signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved;

- Responds by integrating understanding and response to trauma in interactions, care, and policy; and

- Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.

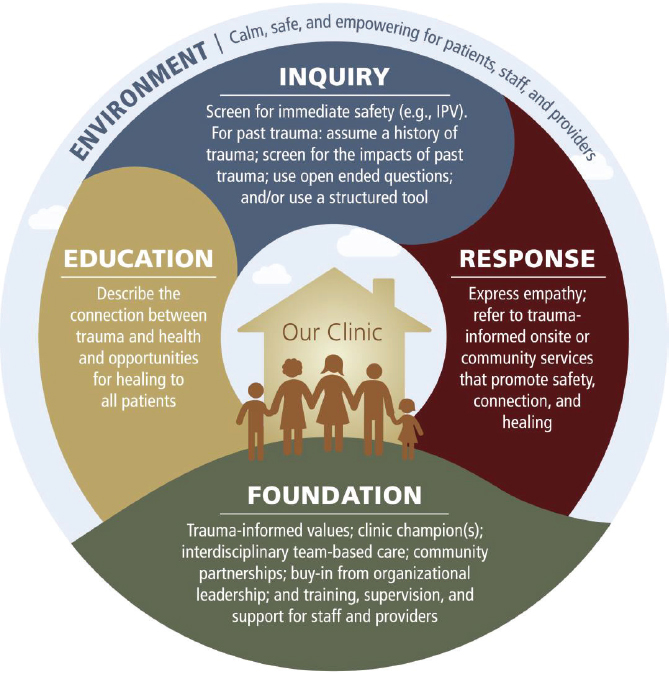

SAMHSA, UCSF, and others have produced models and toolkits to help guide the establishment of trauma-informed practices and clinics (see Figure 1), and the field is now trying to understand how to best package the interventions for which there is evidence supporting their effectiveness.

Machtinger noted that before the Ryan White model of HIV care emerged in the 1990s, the U.S. health care system was struggling with the ongoing AIDS epidemic. Early AIDS patients, as with most people with SUD and mental illness, were from highly marginalized populations, and they faced a stigmatizing and often uniformly fatal illness. At the time, clinicians did not have the expertise or tools to effectively fix the problem in front of them. Most care, explained Machtinger, was provided in hospitals at the end

NOTE: IPV = interpersonal violence.

SOURCES: As presented by Edward Machtinger, October 15, 2019; Machtinger et al., 2019.

of life, and there was limited understanding of how to integrate HIV care into primary care.

The Ryan White Care System8 currently serves more than half of the people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, or almost 600,000 people, and after 30 years of operation, it has become the nation’s safety net for people living with HIV. “The revolutionary power of Ryan White comes from how it funds outpatient treatment and care,” said Machtinger. “It specifically supports

___________________

8 For more information, see https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program (accessed December 4, 2019).

integrated team-based primary care with an emphasis on wraparound services, such as social work, case management, therapy, and medication adherence.” This system requires clinics to integrate individuals living with HIV into the decision-making process for how care services are delivered and drives the integration of community-based organizations (CBOs) and peers into onsite care delivery through a structure of shared funding between CBOs and primary care clinics. “Despite Ryan White serving predominantly low-income patients, it has far better outcomes than clinics that have private insurance,” he noted. Machtinger estimated that if this model were extrapolated to the opioid epidemic, it would cost about $100 billion over 10 years, which he said is a fraction of what the opioid epidemic is costing the nation.9

In closing, Machtinger pointed out that trauma-informed care provides values and provider-level guidance, while the Ryan White model provides the crucial systems-level platform. “The combination of this platform and these values is necessary and possible for addressing our substance use epidemic,” said Machtinger. As a warning, he implored the workshop participants to be wary of being “mesmerized by purely biomedical solutions to problems that are fundamentally relational. The Ryan White system of AIDS care was at its best when new, effective biomedical treatments were integrated into a system that saw people as people and did everything they could to help them survive,” he said. “That combination was the best care this country has ever provided, and we have a rare opportunity right now to realize that model of care for substance use and mental illness,” concluded Machtinger.

Creating Hope Through Person-Directed Care, Decision Negotiation, and Collaboration

Lisa St. George, the director of recovery practices at RI International, finds that she works in a field full of hope and possibility—an attitude that she tries to inspire in the people that she and her colleagues serve. “It is of such importance that the people that we work with know and understand that everything can change for them,” said St. George. While acknowledging that every person will have a unique journey of recovery, she pointed out that every single person has the possibility of achieving a full recovery.

Recovery, explained St. George, does not mean people will never have a symptom of their illness again, that they no longer need to take medication if they have a mental health challenge, or that they will not battle addiction every day of their lives. Rather, recovery means that they do all of those things

___________________

9 A 2017 study estimated that the opioid epidemic is costing the United States more than $500 billion per year (Council of Economic Advisors, 2017).

while living a full and complete life. She noted that many health care clinicians believe they do not know how to inspire hope, but in her opinion, that does not take much training or a massive change to the way they work. She added that inspiring hope requires looking through the lens of what is possible for people rather than what is not possible. That change in focus can inspire hope even when people are struggling in their worst moments, stated St. George.

In the past, hospitals had limited visiting hours that had the effect of isolating patients from their loved ones and friends—the very behavior that those in recovery are asked to avoid. “We want people to be among those that give them comfort and support,” said St. George. In the same way, patients were often told what to do rather than being asked to be full participants in planning their care. “Person-centered care does not occur if the individual is not present,” St. George noted. Nor does it occur, she added, if the individual does not have an equal voice among all those who are involved in formulating and carrying out a care plan.

According to St. George, the key to achieving true person-centered care is collaboration through negotiation, which involves three key components:

- Identifying negotiation and collaboration guidelines,

- Assuming that all partners on a care team—including the individual—have valuable and valid knowledge, and

- Ensuring that all voices are heard and respected.

Compromises and trial runs are an acceptable part of the collaborative care through negotiation process, St. George noted, but everyone must stay in the discussion even in difficult areas where reaching an agreement may be a challenge. In addition, when the individual being served wants to do something different than what the rest of the team wants, that individual should still receive support.

St. George explained that within the context of the collaborative care negotiation team, everyone takes strategic risks and individuals and team members grow to trust one another. When a person is a full participant in their care planning, everyone ends up sharing the weight of the resulting plan, and when a person makes choices about what they want, they gain self-confidence. This self-confidence, in turn, moves people toward their strengths and away from helplessness and helps them realize they are effective decision makers and that they can learn from errors. The end result is that people stay engaged and invested in their well-being. Peer supporters are trained to work in this self-directed, self-guided, and negotiated manner. “They work that way because they are perfectly equal with the people that they are serving, and they work from a knowledge base of ‘I have been through that and I understand what you are going through,’” she said. Peer supporters, she explained, do not direct

the work that people do with them, and they support thoughtful risk when people want to try something new.

St. George shared that 100 percent of the individuals served by RI International’s peer transition teams report that they are satisfied with the process and outcomes they achieve. In addition, the RI International peer transition teams program has demonstrated the ability to reduce both the number of people hospitalized (from 159 to 30) and the number of times an individual requires hospitalization (from 202 to 40) (Optum, 2015). St. George noted that one health system has seen a 58 percent increase in individuals served over a 5-year period by a program that includes peer support, resulting in a 32 percent reduction in hospitalizations and $12.1 million in cumulative savings over those 5 years (Optum, 2015). This program also led to a 33 percent reduction in Involuntary Treatment Act admissions, an additional $10.3 million in savings, and a 32 percent reduction in 30-day readmission rates and $1.1 million in cumulative savings over the 5-year period (Optum, 2015).

Discussion

In the discussion session following the speaker presentations, Kenneth Stoller from Johns Hopkins University asked St. George to reflect on the possibility that patients’ lack of hope might result from clinicians not appreciating how people can improve if granted access to comprehensive treatment, which could include trauma-informed care. She replied that a big part of the problem is that most patients see their primary care physician, who has 15 minutes to assess what they need and will likely miss a large piece of what is happening. In St. George’s view, this is why community treatment is important, as it creates the opportunity for health care providers and peer supporters, for example, to spend more time with people and come to understand what the patient truly needs in order to fully engage with their treatment.

Stoller also asked Machtinger if trauma-informed care can be packaged for office-based practices providing primary care. Machtinger said this was indeed possible and noted that SAMHSA has published federal guidance for delivering trauma-informed care in behavioral health settings. In addition, he noted, there has been a national effort to publish guidance for trauma-informed primary care that should result in the National Council for Behavioral Health doing so.10 This latter guide and accompanying materials can serve as a prescriptive toolkit to help clinics transition from trauma-inducing environments to trauma-responsive environments, Machtinger explained.

___________________

10 Additional information is available at https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/consulting-areas-of-expertise/trauma-informed-primary-care (accessed November 11, 2019).

Andrew Pomerantz, the national mental health director for integrated services in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention and an associate professor of psychiatry at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth asked the panelists if they had seen any of the cost savings resulting from delivering trauma-informed and recovery-oriented care reinvested in expanding that type of care. St. George replied that she would like to think that those who invest in funding that type of care would reinvest that way, but in truth, she has no idea what funders do with those savings. “Investing that money back into the system of care, into peer support, and into recovery-focused services is vital to make those savings be of use to us rather than going into funders’ pockets,” said St. George.

Machtinger added that cost savings in medicine are unequally distributed, so increased spending for primary care and behavioral health, for example, will translate into savings from lower emergency department (ED) use and fewer hospital admissions. At the same time, he said, primary care and behavioral health are often held accountable for increased spending without considering the broader cost savings created by increased expenditures in both sectors. “That is why I feel so strongly that we need to have a more structured national response to substance use and mental illness that really looks at this holistically and does not rely on innumerable valiant but fragmented efforts throughout the country to accomplish what we really see as shared goals,” he said. The only place that he sees such a holistic approach in action is in the VA.

Myrick referenced legislation proposed in California that would have approved a process for peer providers to be state certified. Though peer certification has been shown to provide a return on investment in the form of reduced hospitalizations, longer tenure in the community, and people being able to leave the public support system and return to work, the concern was the cost of setting up the program. The governor ultimately vetoed the bill. As someone with a business background, Myrick said she was interested in how best to argue for supporting these programs that demonstrate value and savings.

Tisha Wiley from the National Institute on Drug Abuse noted that each of the speakers had stressed the importance of building on family relationships to support a family member’s recovery, which for her raised the question of how the panelists manage some of the tensions inherent in providing patient-centered care and supporting families that have also suffered traumas created by their family member’s drug use. For example, Pebbles’s grandchild experienced several traumas and likely requires support and care related to her own individual traumas. Machtinger replied that the most troubling aspect of Pebbles’s case was that Pebbles, whom everyone loved, had hurt Lily through her behavior. “The single most important thing we can do to help protect children from abuse is to take care of their mothers and fathers, help them

to end their drug use, help them not die, help them stay out of prison,” said Machtinger.

Karen Drexler from the VA asked Machtinger if he and his team considered contingency management,11 also called “motivational incentives,” as a treatment for Pebbles’s drug use to reinforce abstinence and engage her quickly and effectively. Such incentives, Drexler explained, are typically delivered as a reward for negative urine tests. Machtinger said he and his team use contingency management informally with a gift card program to incentivize actions that help patients survive, such as going to get needed care. He added, however, that he intended to learn more about this approach as a potential tool for his program.

IDENTIFYING ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF CARE BY DEFINING WHAT MINIMALLY ADEQUATE CARE WOULD BE ACROSS DIVERSE CARE SETTINGS

Susan Essock, the Edna L. Edison Professor of Psychiatry, Emerita, at Columbia University, stated the charge for the second session: given that research has outlined what the optimal interventions are for MHSUDs, the panelists were asked to identify the essential components of care for different disorders and ways to monitor whether effective care is being provided.

The Veterans Affairs Integrated Care Experience

Andrew Pomerantz began his presentation by reviewing the lessons learned from systematic research on translating evidence into practice:

- Screening alone is at best inadequate to improve care;

- A collaborative care model improves outcomes with limited initial cost;

- Health psychology improves outcomes for many conditions;

- Colocation of mental health and substance use services in primary care settings is necessary but not sufficient for improving care;

- Measurement-based care improves clinical outcomes at the same or lower cost as traditional care; and

- Peer support improves engagement in treatment, leads to better outcomes, and saves money.

___________________

11 For more information, see https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/evidence-based-approaches-to-drug-addiction-treatment/behavioral-0 (accessed December 2, 2019).

Pomerantz noted that he is currently leading the VA’s effort to implement a congressionally mandated program to integrate mental health peer specialists into primary care. Even though he had the funding to pay for the peer specialists, management at some of the 15 VA facilities where he started this program were resistant because they believed their facilities needed another clinician, not a peer. “People still see peer support as a luxury,” Pomerantz pointed out.

In Pomerantz’s view, it is most important to focus on what brings patients to the clinic for treatment. In fact, he said, people who come for help most often fail to return for follow-up treatment because they are not getting what they need from treatment. “We tend to be the only specialty that does not start with a patient’s chief complaint as the problem to be addressed,” said Pomerantz, “but if we start with what seems to be the main problem, we help a large number of patients.”

Based on his experience and that of others in the field, Pomerantz felt that many stakeholders oppose moving mental health care into primary care as part of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (a model where treatment is coordinated through a patient’s primary care physician) (Croghan and Brown, 2010). Yet, evidence is growing that providing integrated care and providing team-based care is essential for providing the best care for individuals with MHSUDs. He explained that this is why the VA is working hard to integrate mental health care and primary care in the Patient Aligned Care Teams that are the VA’s version of the patient-centered medical home.

Pomerantz noted that VA integrated care has two key components. The first is co-located collaborative care that embeds a mental health clinician in the medical home team to provide consultative advice, problem-focused assessment, and brief interventions, typically delivered in up to four to six 30-minute visits. The medical home provides population-based care for mental illness, SUDs, and health-related behavior change using evidence-based treatments that the VA adapted and tested for use in the primary care setting.

The second component, care management, uses the collaborative care model12 that relies on telephone-based patient follow-up methods to track symptoms, help patients with medication adherence, and connect the consulting psychiatrists with the primary care provider. One benefit of this model is that it eliminates the 1- to 2-hour extensive initial evaluation that drives many patients away from treatment; instead, it focuses on the problem at hand and is combined with proactive follow-up. Pomerantz pointed out that across VA clinics nationally, patients have an average of two to three appointments to receive evidence-based brief interventions developed specifically for primary

___________________

12 Additional information is available at https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/learn (accessed November 11, 2019).

care. Patient-reported outcome measures guide initial assessments and ongoing treatment decisions. However, one issue for consulting mental health professionals is that they do not currently receive workload credit for spending time helping the primary care physician determine their patients’ next steps. Pomerantz noted that he is working on addressing this issue.

Pomerantz explained that the facilities that have implemented this model have realized clinical outcomes that are as good, or better, than those from specialty mental health care. Other positive outcomes for VA facilities that have implemented the integrated care model include

- Improved identification and treatment in the primary care population;

- Improved engagement and continuation of care if referred to more intensive levels of treatment;

- Reduced demand for specialized mental health care;

- High patient and provider satisfaction;

- Increased likelihood of guideline-concordant care;

- Improved use of antidepressants by primary care providers;

- Reduced no-shows; and

- Significant cost savings, by both shifting more mental health care to primary care and reducing no-shows and non-engagement rates.13

Pomerantz noted that there are challenges with this model, however, including reimbursement issues, unmet training needs, maintaining advanced clinical access, developing the evidence base for the brief interventions, and the need to consistently show that this approach results in cost savings while improving people’s lives. Pomerantz also identified the need to change the culture that makes it difficult to adopt team-based care. The bottom line, said Pomerantz, is that many, if not most, patients can be adequately treated by doing only a few things differently (see Box 3).

Going forward, Pomerantz suggested expanding telehealth and mobile technology to reach more individuals and mobile technology to provide clinician-directed and supportive care that helps the patient manage their own care. He noted that there are innovations under way to use the collaborative care model for opiate use disorder, for example, and to address more complicated illnesses in primary care by providing additional mental health resources to primary care—rather than adding primary care to mental health clinics.

___________________

13 For more information, see https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/impacts/pc-mhi.cfm (accessed January 8, 2020).

Can We Provide Necessary Care for Substance Use and Mental Health Disorders in the United States?

Access to treatment for MHSUDs is among the greatest health care disparities in the United States, said Shelly F. Greenfield, the Kristine M. Trustey Endowed Chair of Psychiatry and the chief academic officer at McLean Hospital and a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. This disparity exists despite the high prevalence of these disorders, the current dual public health crises of opioid deaths and suicide, and the availability of evidence-based treatments. It has developed, in Greenfield’s view, due to three factors:

- A chronic lack of a coordinated and integrated treatment infrastructure,

- A lack of a trained multi-disciplinary treatment workforce, and

- A longstanding stigma associated with these disorders.

According to Greenfield, addressing this problem will require a multilevel, linked, and integrated health system and a trained workforce that can deliver the multiple necessary components of care. Greenfield noted that, according to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health,14 57.8 million Americans had a mental health and/or substance use disorder in 2018. Approximately 19.3 million people aged 18 years and older had an SUD, 47.6 million Americans 18 years and older had a mental illness, and 9.2 million people 18 years and older had both an SUD and a mental illness (SAMHSA, 2019). Moreover, among people with an SUD aged 12 years and older or 18 years and older, nearly 90 and 57 percent, respectively, did not receive treatment (SAMHSA, 2019). Greenfield noted that of the 30.3 million Americans who had diabetes in 2015, more than three-quarters were diagnosed—compared to the situation for SUD and mental illness, where just more than 10 percent and 43 percent of patients, respectively, received treatment in 2018 (SAMHSA, 2019).

Greenfield pointed out that overcoming the technical challenges related to putting men on the moon in 1969 was accomplished more readily than harnessing the political will to build the needed infrastructure and capacity to solve this profound health care disparity in the United States. She referred to the tripartite model of innovation and change in public health and health care, developed in the 1980s and 1990s as something that could bring about needed changes (Richmond and Kotelchuck, 1991). According to this model, Greenfield explained, innovation and change can occur when there is a knowledge base with evidence of effective treatments, a social strategy that prioritizes policies to act on that knowledge base, and the political will to make change happen.

One example of the lack of political will, said Greenfield, is apparent in the fact that while the Institute of Medicine (IOM)15 issued Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems (IOM, 1990) as a blueprint for combining a comprehensive continuum of treatment that combined community and specialized treatment to improve alcohol use treatment, little has been done to follow that blueprint. One possible result of inaction has been a nearly

___________________

14 Available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.htm (accessed January 9, 2020).

15 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the IOM. The IOM name is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

50 percent increase in 12-month prevalence of alcohol use disorders in the United States since 1990 (Grant et al., 2017) despite many excellent models of comprehensive continuum of treatment (Modesto-Lowe and Boornazian, 2000; Rehm et al., 2016; Rivara et al., 2000).

“Why does this not get done?” asked Greenfield. She observed that at the practitioner level, the reasons include lack of time, inadequate or no training, no reimbursement, no idea of where to send patients for services, and not knowing that patients are treatable. “The reasons are the same today as they were 10 years ago and 20 years ago,” she noted. At the systems level, the reasons include the lack of reimbursement, absence of linkages to services, inadequate institutional or workforce capacity, and stigma in health care organizations, among health care providers, and in the community, said Greenfield. She pointed out that one result of not building the infrastructure and workforce to effectively treat MHSUDs is that the country has been unable to respond promptly to the opioid epidemic.

In 2019, the National Academies released Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives (NASEM, 2019b). The report presented research indicating that the three evidence-based treatments available for opioid use disorder (OUD) save lives, prevent relapses, reduce criminal activity and infectious disease transmission, increase retention in treatment, and increase social functioning. Such treatments are also completely underutilized, which is particularly galling, noted Greenfield, in the face of the deaths occurring from opioid use.

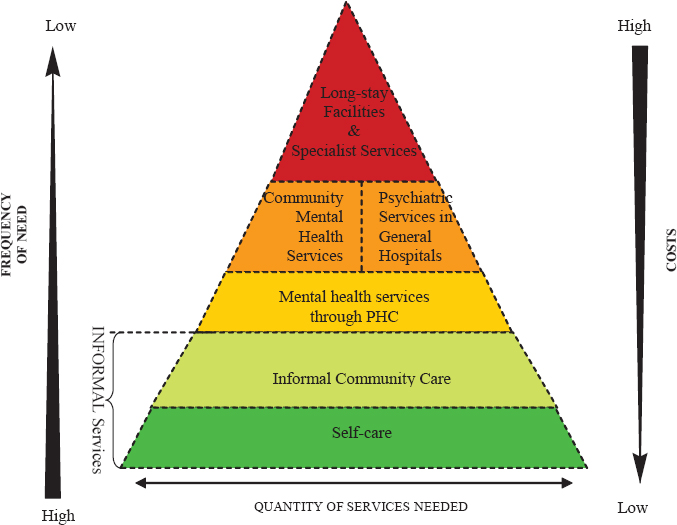

What the nation lacks, said Greenfield, is a coordinated, integrated treatment infrastructure, with linkages between the necessary components of care, and a trained workforce to cover all areas of the treatment infrastructure. She argued that strategies to address these deficiencies can be based on lessons learned from the experience of high-performing health plans with treatment initiation and engagement for substance and alcohol use disorders. Other lessons can be drawn from the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Service Organization Pyramid for integrating and linking the necessary components of care (see Figure 2).

Researchers have used the WHO pyramid to argue that three interlinked services or platforms of care—self-care and informal health care, primary care, and specialty care—are needed to meet all mental health needs. “Each platform is an essential component of care, as are the linkages among them,” said Greenfield. She added that “in the United States, we have at various times focused on one platform or another platform, but we have not focused on all of these platforms simultaneously, and the linkages between them.”

WHO defines self-care as including wellness practices, mindfulness, yoga, exercise, and activities designed to relieve stress, while the informal care system includes individuals such as peers, traditional healers, family associations, faith-based counselors, and recovery coaches. The informal care system also

NOTE: PHC = primary health care.

SOURCES: As presented by Shelly F. Greenfield, October 15, 2019; WHO, 2003.

includes activities that build mental health literacy throughout the community to enable better recognition of the signs and symptoms of these disorders and awareness about effective treatment options.

The primary health care system is the fundamental and first component of care in the formal health care system, noted Greenfield. In her opinion, primary health care is often more accessible, affordable, and acceptable for individuals, families, and communities than specialty care, and it is a place where mental health and SUD services are most likely to be integrated with other medical issues an individual might be facing. Primary care is also likely to be where collaborative and stepped approaches to care occur, she explained.

Specialty care, noted Greenfield, is where psychiatry and addiction services are located. These include general hospital psychiatry units that are well staffed with trained providers, specialty mental health and addiction programs, community mental health centers and addiction treatment programs, opioid treatment programs, and residential treatment centers that combine hospital- and outpatient-based care.

“Every single one of these platforms is necessary to provide care, and linkages between and among them are necessary,” said Greenfield. Without those linkages, she added, the system does not work.

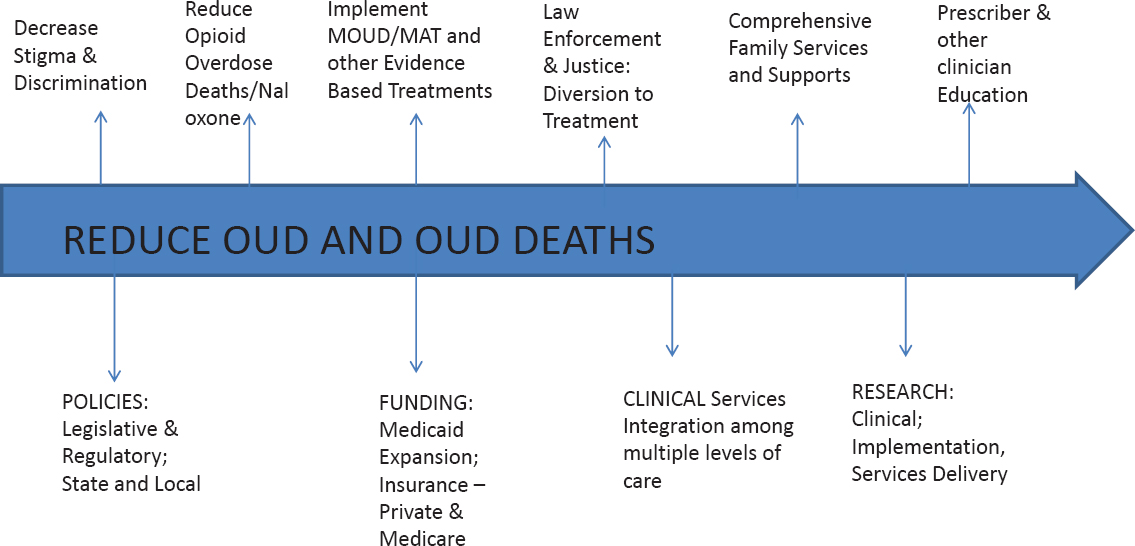

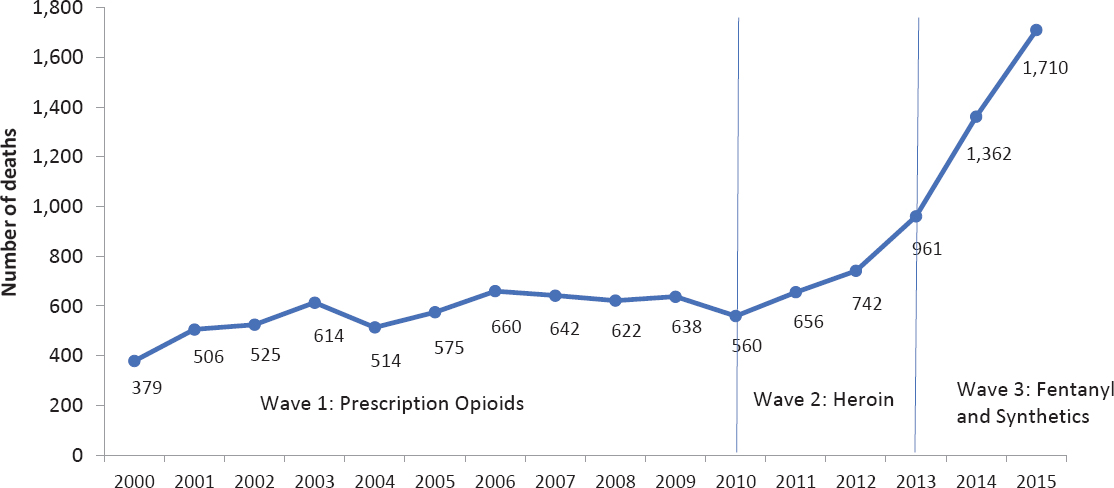

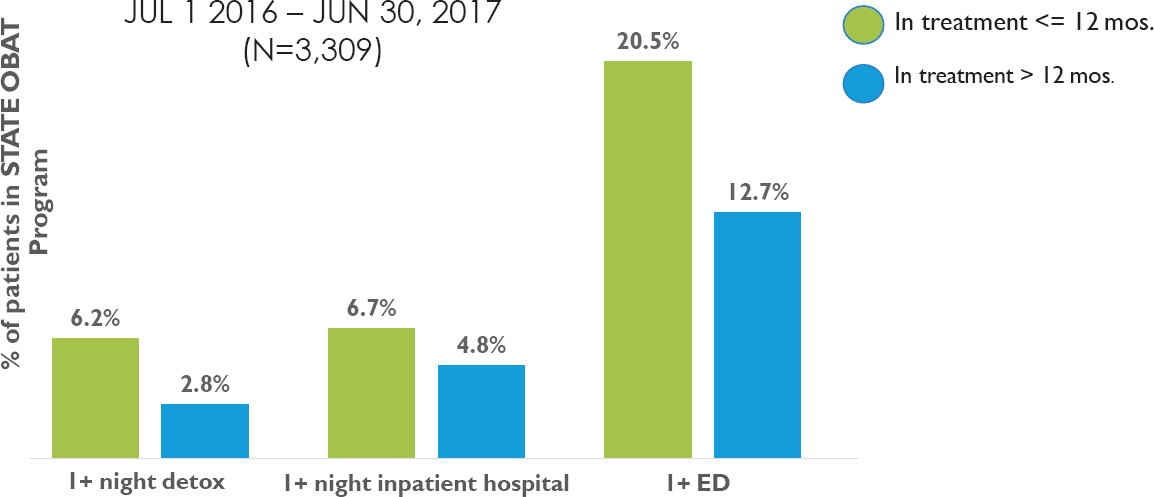

As one example of policy changes and necessary linkages among components of care for MHSUDs, Greenfield noted the lessons learned from a conference at McLean Hospital that convened state and local government officials, treatment experts, law enforcement officials, and representatives of community-based agencies from the 10 states most heavily affected by opioid overdoses (see Figure 3).

Greenfield also referenced a 2019 study that examined best practices for treating, initiating, and engaging people for SUD and OUD treatment among 400 health plans. The study found that, with respect to initiation and engagement, high-performing plans were associated with higher rates of outpatient services, intensive outpatient services, and partial hospitalization16 (O’Brien et al., 2019). The study also identified three common themes among plans with higher rates of engagement and initiation of treatment:

- The care model was focused on care coordination, including physical, mental, behavioral, and SUD-specific services.

- Benefit design required no prior authorization for outpatient treatment and medication for OUD and included coverage for at least two MAT options and naloxone; Medicaid plans had no out-of-pocket costs for covered services.

- There was open communication among health care providers and beneficiaries, including the availability of secure electronic messaging and outreach teams trained to communicate effectively.

In addition, the study identified barriers to treatment, initiation, and engagement and a number of potential solutions to address those barriers (see Table 2). The last barrier—that plan members have competing needs such as housing and child care—is one potential explanation for high-performing health plans have fewer female beneficiaries seeking treatment, as females are more likely to have these roles and responsibilities, said Greenfield.

___________________

16 Partial hospitalization refers to an intense, structured treatment setting for individuals who have difficulty maintaining current daily routines or would otherwise require inpatient behavioral health care (O’Brien et al., 2019).

NOTE: MAT = medication-assisted treatment; MOUD = medications for opioid use disorder; OUD = opioid use disorder.

SOURCE: As presented by Shelly F. Greenfield, October 15, 2019.

| Barriers | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|

|

|

SOURCES: As presented by Shelly F. Greenfield, October 15, 2019; O’Brien et al., 2019.

Building on these lessons learned, Greenfield suggested a number of strategies to deliver the necessary components of mental health and SUD care, including

- Incentivize the workforce to see patients in multiple settings for screening, assessment, referral, and treatment;

- Build capacity through training;

- Provide access to levels of care in all the necessary delivery platforms;

- Acknowledge multiple co-occurring disorders, and build in mechanisms and incentives for identification and treatment;

- Use technology to address wide gaps in care and in training;

- Model and assess outcomes across multiple sectors prospectively and longitudinally;

- Address the stigma barrier by society and clinicians, as well as self-stigma; and

- Restructure payment systems to achieve these goals.

Greenfield stressed that in the area of payment reforms, it will be necessary to incentivize physicians and other health care providers by increasing individual provider payments for needed services, including screening, assessment, and diagnosis, smoking cessation treatment, and prescribing MAT. According to Greenfield, restructuring and reforming the health care payment system (including making changes in Medicare and Medicaid programs to support these goals) would incentivize them to achieve desired outcomes—as would creating a stable, reliable, and predictable funding base to support a coherent system of care. Greenfield also recommended requiring training at all levels of provider education. This would involve training on MHSUDs for nurses, psychologists, social workers, pharmacists, physician assistants, and other professionals involved in an integrated system of care. She emphasized that it will be necessary to push all available policy levers at the same time in order to make real progress.

In closing, Greenfield said the opioid crisis has been superimposed on longstanding failures to provide necessary treatment for SUDs and other mental health disorders in the United States. Moreover, the response to the crisis demonstrates the need for linked, multi-level formal and informal service delivery platforms and supports from other service sectors. She noted that evidence-based treatments are possible at each level of treatment delivery platforms but all are necessary, interrelated, and linked components of care. Ultimately, effective solutions require a multi-level, integrated health system, a workforce trained to provide treatment, and a combination of state and federal policies to address payment and training barriers, concluded Greenfield.

Considering Essential Components of Care While Maintaining a Focus on Behavioral Health Equity

Ruth Shim, the Luke and Grace Kim Professor in Cultural Psychiatry at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, began her presentation by recounting an observation she made when she was a psychiatry resident and split her time between Emory University Hospital—a well-resourced institution in Atlanta’s suburbs—and Grady Memorial Hospital in downtown Atlanta. She observed that the predominantly white patients admitted to Emory with a serious mental illness would get better when provided with inpatient therapy, while the predominantly African American patients admitted to Grady with a serious mental illness would not improve even though they received the same

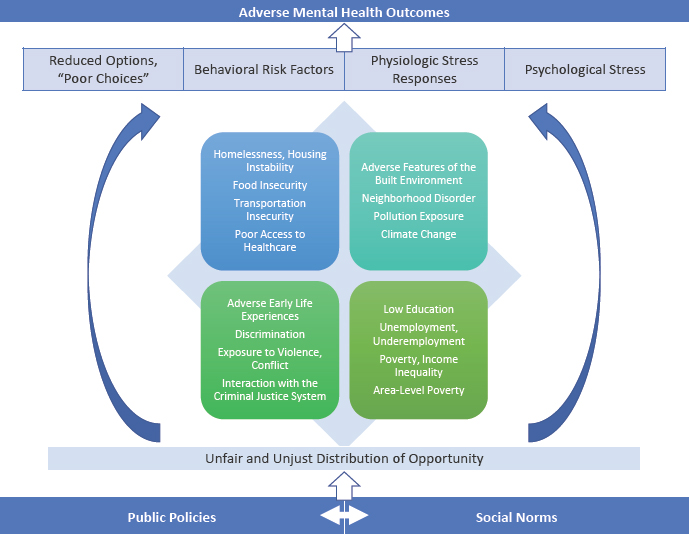

SOURCE: As presented by Ruth Shim, October 15, 2019.

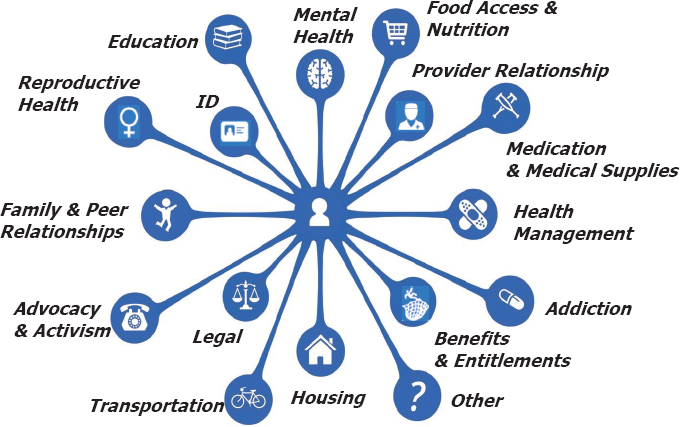

interventions. After considering a number of possible reasons for the differences in outcomes, Shim realized that the root cause came down to the two patient populations’ experiences with the social determinants of health (see Figure 4).

Citing WHO, she defined the social determinants of health, mental health, and behavioral health as “those factors that impact upon health and well-being: the circumstances into which we are born, grow up, live, work, and age—including the health system. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices.” In other words, said Shim, “the factors by which we live are often shaped by the decisions that we as a society make about who gets resources and who does not.”

Shim clarified that there is a difference between health disparities and health inequities. Health disparities are differences in health status among distinct segments of the population, including differences that occur by gender, race or ethnicity, education or income, disability, or various geographic localities. Health inequities are disparities in health that are a result of systemic, avoidable, and unjust social and economic policies and practices that create

barriers to opportunity. “So when we think about all of the disparities that we have been talking about that affect substance use disorders, that affect mental health, that affect all of our health outcomes, are these actually disparities, or are they inequities?” asked Shim. According to Shim, the differences in mental health and mental illness outcomes are inequities, not disparities.

Shim pointed out that the U.S. Surgeon General issued a report in 2001 highlighting that racial and ethnic minority groups have less access to care and availability of care, receive generally poorer-quality mental health services, and experience a greater disability burden from unmet mental health needs. At the heart of this issue, said Shim, lies the concept of social justice, which the political philosopher John Rawls defined as “assuring the protection of equal access of liberties, rights and opportunities, as well as taking care of the least advantaged members of society” (Rawls, 1971). Shim also stressed the importance of understanding the concept of structural racism, a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various often reinforcing ways to perpetuate inequity between racial groups (Bonilla-Silva, 1997). Structural racism, she explained, identifies dimensions of our history and culture that have allowed privileges associated with “whiteness” and disadvantages associated with “color” to endure and adapt over time. Most importantly, said Shim, structural racism is not something that a few people or institutions choose to practice; rather, it has been a feature of the social, economic, and political systems in which everyone exists. In other words, even if all interpersonal discrimination was eliminated from society, inequities in health outcomes would still persist because of how deeply structural racism is entrenched in U.S. society.

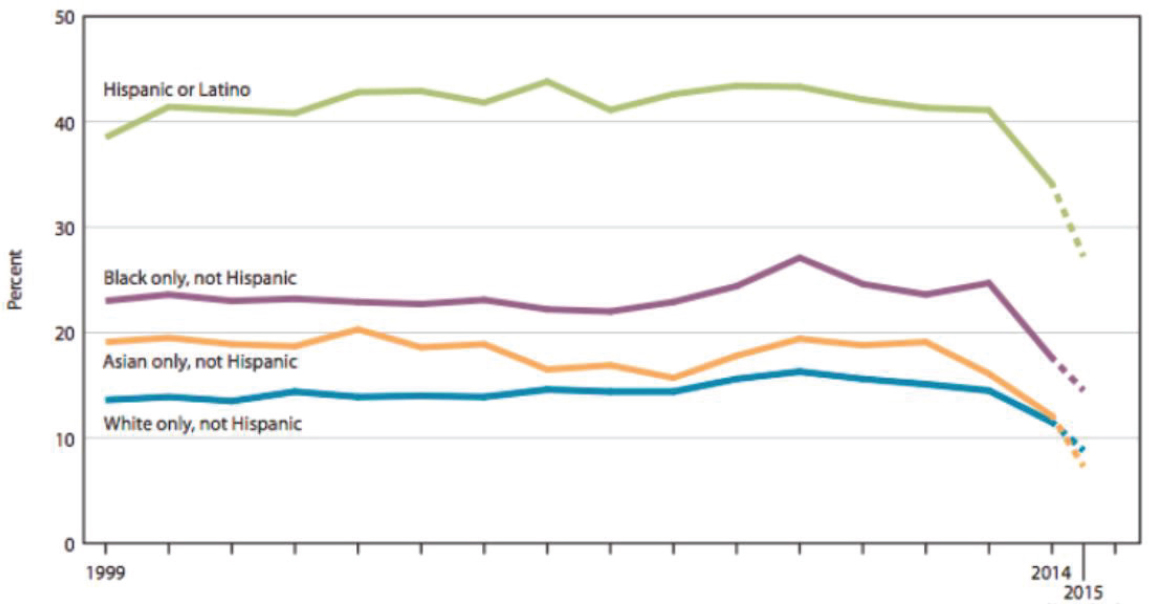

Providing historical context, Shim explained that the Social Security Act of 1935, which allowed generations of people to build wealth in the United States, is an example of structural racism in that it excluded agricultural and domestic workers—the majority of whom were African Americans living in the South. The war on drugs, residential segregation resulting from redlining and other practices, and current immigration policies are other examples of structural racism (Bailey et al., 2017; Gee and Ford, 2011). So, too, is the lack of a national health care system, which Shim claimed came about because of a historical decision by physicians and the American Medical Association to push back against efforts to provide all people access to health care. The end result, she said, is that the percentage of people without adequate health insurance coverage varies markedly according to race (see Figure 5).

Shim emphasized that racism and discrimination substantially affect health and mental health. She called attention to data that support the association of racism and discrimination with poor mental health across a variety of outcomes and mental health conditions, including PTSD, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and alcohol use disorder (Paradies et

SOURCES: As presented by Ruth Shim, October 15, 2019; NCHS, 2016.

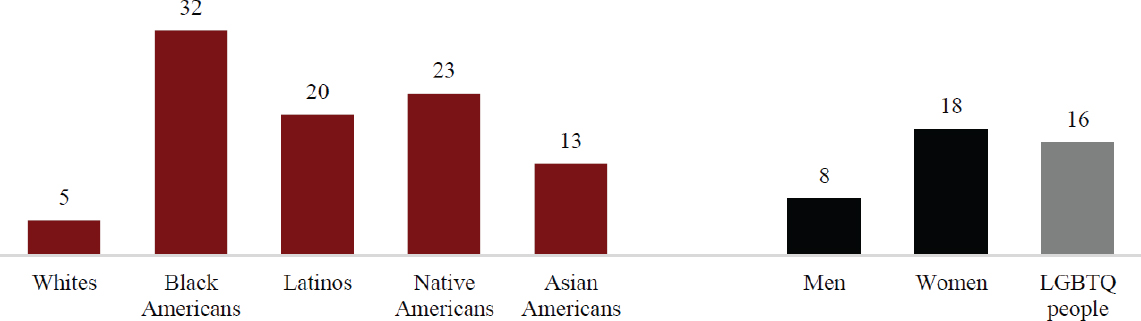

al., 2015). Shim also referenced a 2017 study, which found that 32 percent of African Americans and 20 percent of Latinx report they have been discriminated against when going to a doctor or health clinic (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health et al., 2017) (see Figure 6). “We talk about designing systems that people want to go to, but I think that if you are discriminated against when you go to seek care, you would not necessarily want to return to that type of setting,” said Shim.

Shim also discussed the concept of intersectionality—that there are multiple identities people share within themselves that build on each other—as it relates to MHSUDs (Crenshaw, 1991). Failing to address a person’s multiple identities, she said, means that not all of their needs are being addressed.

Shim described how focusing on social care can be an effective way to address poor outcomes in health, mental health, and SUDs (NASEM, 2019a). Countries with a higher percentage of gross domestic product spent on social care programs (including education, retirement, housing, employment, disability benefits and food security) have longer life expectancies, she said—a finding that also holds true for individual U.S. states (Bradley et al., 2016).

In closing, Shim suggested that the goal should be equity, not equality. Moreover, when defining essential components of care, it is important to appropriately consider the needs of the specific target population.

Implementation Science and Care for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

“Why do large health care systems implement change?” asked Mary Durham, the retired director of Kaiser Permanente’s Center for Health Research. She noted that this is an important question to ask when considering what essential components of care look like in a capitated system.17 Durham stated that capitation has limitations but also allows for greater flexibility in choosing programs and benefits for individuals through clinical care. She pointed out that given that capitated care relies on an evidence base, ineffective and unsafe choices can be eliminated as part of the basis for defining essential components of care for MHSUDs.

Durham explained that large health systems implement change for a number of reasons, including the need to grow market share. This often requires determining which services will be attractive for employers to offer to their employees and negotiating where services are to be delivered and the technologies used to deliver care. Similarly, health systems change as part

___________________

17 Capitation is a type of payment in which a health care service provider is paid a fixed amount per patient for a prescribed period of time by an insurer or physician association.

NOTE: LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning.

SOURCES: As presented by Ruth Shim, October 15, 2019; Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health et al., 2017.

of their drive to obtain a five-star rating from the National Committee for Quality Assurance, which is based in part on behavioral health measures and important for the financial stability of large health care organizations, Durham observed.

She also pointed out that systems implement change related and in response to regulations and lawsuits, Medicaid expansion, new medical evidence, and a vocal clinical champion for change. She noted that state regulations can provide opportunities to include measurement as part of the data required in health care system reporting. Additionally, real or threatened lawsuits can provide opportunities to raise awareness about the social determinants of health, said Durham. She added that, with this awareness, researchers can examine the impact of an investment in the social determinants of health on an individual’s health and safety.

Durham noted that important drivers of organizational change include the need to save money and address labor shortages. Durham commented that a desire for long- versus short-term return on investment will affect whether some health care organizations will implement evidence-based programs. For example, medical homes are presumed to improve care coordination and cut costs, but the degree to which they gain traction will depend on whether the systems implementing them will realize a fairly quick return on investment.

According to Durham, labor shortages can also impact whether large health systems implement change. Health care systems may not have a choice given an absence of primary care providers, or they may be required to use other providers to fill those roles. She noted that primary care has been redesigned many times in an attempt to improve care delivery and produce cost savings. Information system implementation can also drive change, as systems must respond to changing evidence and technologies. Perhaps the most forceful driver of change, in Durham’s opinion, is a clinical champion; she has seen examples of these champions—health care providers, chief executive officers, or board members—creating change by demonstrating unexpected evidence.

Durham noted the importance of evaluation: bright ideas without solid and specific evidence of effectiveness and a strong return on investment will not be acceptable in practice to health care plans. Additionally, health systems may need to critically reevaluate common frameworks and models to meet the needs of the current population.

In conclusion, Durham cautioned that unsettled health care policies due to fluctuating politics can also impede change, due to regulatory or legal uncertainty and changes in federal funding. However, factors such as progress in technology, artificial intelligence, addressing the social determinants of health, and financial incentives for quality measures represent promising advancements that could contribute to health systems change.

Discussion

In the discussion session following the speakers’ presentations, Missy Rand from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors asked Pomerantz if there are specific screening tools he has used consistently that look at mental health screening, substance use screening, and suicidality. Pomerantz responded that good mental health care requires a clinical pathway to address a positive screen and not just screen for the sake of complying with an accreditation requirement or getting paid. Toward that end, and with the increasing focus on suicide prevention, the VA has instituted a multi-step suicide screening process18 that Pomerantz noted eventually led to a more comprehensive suicide risk and safety planning evaluation.

Abigail Wydra from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General asked Greenfield if she could describe what successful linkages look like. Greenfield replied that practitioners voice frustration with not being able to move people to and from the levels of care they need. For example, her primary care colleagues see patients with profound MHSUDs that they were never trained to address, and yet they have trouble finding psychiatric care or community-based care for these patients. Similarly, an inpatient psychiatric care facility may have trouble referring patients to community-based care. This is a solvable, human-made problem, said Greenfield, but it will require finding ways within Medicare and Medicaid to incentivize creating those linkages. Greenfield suggested that the first step would be to adequately pay providers who treat MHSUDs. Essock added that it is important to find ways to design a system that will incentivize spending on effective treatment approaches that generate good clinical outcomes, and this requires building relationships that instill hope and trust.

Stephanie Guerra with the VA Office of Research and Development asked the panelists if there are intentional strategies to ensure programs can be sustainable over the long term, once initial funding has ended. Pomerantz replied that this is a challenge because much of the payoff occurs over the long term, even though many programs can demonstrate some short-term success. Durham commented on the importance of having clinical champions, who can tout those short-term clinical successes, and regulations that set minimum standards. Shim agreed that regulations and policies are needed to support long-term implementation of effective programs.

Michael Freed from the National Institute of Mental Health asked the panelists for their thoughts on evidence standards that might inform funding and adopting interventions. Greenfield replied that the problem is not a lack

___________________

18 For more information, see https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADODCP_suiciderisk_full.pdf (accessed December 3, 2019).

of evidence-based treatments. In fact, she applauded the work the research community has done on the efficacy and effectiveness in clinical trials for both behavioral and pharmacotherapeutic treatments for MHSUDs. In her opinion, the problem is a lack of multiple integrated and linked platforms of care to deliver those interventions. Pomerantz added that evidence-based medicine is only part of the equation; the other part is the individual person being treated. Pomerantz recalled when he had a patient with PTSD and tried to treat him with cognitive processing therapy. That did not work for him, but he began to heal when he was given dentures. According to Pomerantz, the dentures made him more socially acceptable, and that had a significant impact on his mental health and well-being.

Dawn Wiest from the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers and the National Center for Complex Health and Social Needs asked the panelists for ideas on how to reconcile the fragmentation in research and within delivery systems to create a dialogue around scalable evidence. Pomerantz’s idea was to expand studies to look at outcomes beyond health and cost and find ways of evaluating the effect of an intervention on presenteeism and absenteeism, family members, and other non–health care outcomes. Greenfield agreed with that idea and added the suggestion to hold convenings that bring together people from different systems to learn from one another and create a system that combines the evidence base and the implementation of that evidence base in the real world.

PROMISING STRATEGIES TO TRANSLATE KNOWLEDGE INTO PRACTICE AND MONITOR IMPLEMENTATION

Opening the workshop’s third session, moderator Anita Everett, the director of the Center for Mental Health Services at SAMHSA, noted that her agency has addressed the challenge of improving care for individuals with MHSUDs by breaking it down into three components:

- The “front door problem,” which focuses on the problem of increasing access to care;

- The “black box” of what happens in the treatment setting; and

- The “exit strategy,” or how the system deals with individuals in terms of whether they need episodic or ongoing treatment.

The focus of this workshop panel, explained Everett, is on the black box component, or the overly variable system of care in the United States. “What people get in that box, whether it is primary care, specialty care, or even more intensive residential style care, is extremely variable across our country. One of

the reasons for that variability has to do with the way that we implement or do not implement those kinds of services,” said Everett.

Harnessing Implementation Science to Realize the Promise of Evidence-Based Practice

Rinad Beidas, an associate professor of psychiatry and medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and the director of the Penn Implementation Science Center at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, began her presentation with a personal story to illustrate why she believes implementation science can be a valuable tool for transforming health and mental health. She described that while doing her clinical training to become a psychologist, she began to observe a troubling pattern of clinicians in the community not using evidence-based practices, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, to treat children with mental health issues. The result was that these children were not improving. This realization, she explained, changed her career trajectory and sent her down the path of focusing on implementation science as a potential solution to this problem.

Beidas explained that it takes approximately 17 years for 14 percent of research to make its way into practice (Balas and Boren, 2000; Morris et al., 2011). “I think we can all agree that is unacceptable,” said Beidas, which is one reason she believes in the importance of applying implementation science to mental health and substance use treatment. Implementation science, she explained, is about making sure that people are receiving care and treatment approaches that have been demonstrated to work in the community to move the needle in health and mental health. Beidas explained that implementation science is the scientific study of methods to promote systematic uptake of proven clinical treatments, practices, and organizational and management interventions into routine practice, and hence to improve health (Eccles et al., 2012; Grimshaw et al., 2012). At its core, she noted, implementation science is about clinician behavior change within organizational constraints. Contextual differences across sites and organizations can provide important lessons going forward, observed Beidas. Importantly, Beidas noted, implementation science only deals with evidence-based interventions. “We want some evidence for what we are trying to implement or scale up,” she said.

As an example of ways in which she has applied concepts of implementation science, Beidas described some of the work in Philadelphia’s large public mental health system, which treats more than 150,000 individuals per year, including 30,000 children and families (Beidas et al., 2016b). Starting in 2007, the newly appointed commissioner of the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services began a number of efforts to transform the sys-

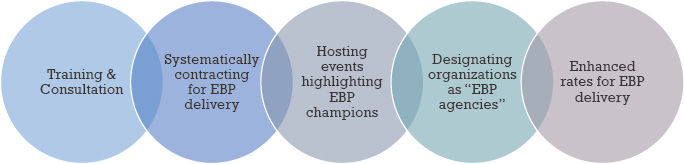

tem to one of recovery by implementing evidence-based practices—particularly cognitive therapy, prolonged exposure, trauma-informed cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and parent–child interaction therapy—in the city’s public mental health system. After a few years, Beidas explained, the commissioner noticed that there were common challenges implementing these evidence-based practices. In response, he convened a public academic task force in 2013, the Evidence-Based Practice and Innovation Center, to serve as the centralized infrastructure to support the implementation of evidence-based practices (Powell et al., 2016). The task forced developed five key components to support implementation of evidence-based practices (see Figure 7).

The first component involved educating clinicians on evidence-based practice and providing them with ongoing support aligned with recommendations from leading treatment developers, said Beidas. The second component relied on a unique situation in Philadelphia—a single-payer system for all Medicaid services falling under the umbrella of community behavioral health—that enabled the city to encourage health care providers to use evidence-based guidelines in contracts for service. A third component involved hosting events that highlighted evidence-based practice champions and individuals who had benefited from those practices. As these practices diffused through the system, organizations acquired the designation as evidence-based practice agencies, which led to enhanced rates for delivering such practices, noted Beidas.

To observe what happens when a large health care system, such as Philadelphia’s, implements a centralized infrastructure to support evidence-based practice, Beidas and her colleagues launched a 5-year prospective mixed-methods observational study of the 29 agencies that serve more than 80 percent of the children and families receiving outpatient mental health services. Nineteen agencies, with 130 therapists, agreed to participate, with others joining in subsequent years. One of the first questions the team examined was whether clinical or organizational characteristics played a role in determining how well evidence-based practices were adopted. The data showed that organizational

NOTE: EBP = evidence-based practice.

SOURCES: As presented by Rinad Beidas, October 15, 2019; Powell et al., 2016.

factors explained more of the variance in the use of evidence-based practices, while therapist factors explained more of the variance for non-evidence-based practices (Beidas et al., 2015). These results, noted Beidas, suggest the importance of targeting organizational factors when thinking about implementation approaches and clinician factors when thinking about changing patterns of existing clinician behavior.