This chapter focuses on behavioral and biological convergence in brain health. Presenters and panelists discussed the connections and discontinuities between brain activity and behavior as well as those between psychological health and brain health. They examined what behavior and life experience may suggest about brain health and resilience. The biological underpinnings of behavior in the context of cognition, emotion, and psychiatric disorders were also explored. Monica Rosenberg, assistant professor in the department of psychology at the University of Chicago, provided an overview of the neural correlates of attention and cognition. Elizabeth Hoge, director of the anxiety disorders research program at the Georgetown University Medical Center, considered the question of whether meditation can improve health and resilience.

NEURAL CORRELATES OF ATTENTION AND COGNITION

Rosenberg explored the neural correlates of attention and cognition by describing how attentional and cognitive processes can be characterized using predictive models based on brain data. She described the concept of brain health as generally involving our ability to safely and successfully navigate the world around us. Attention is a major cognitive process that is the cornerstone of the brain’s executive functions. It is important for life outcomes across development (e.g., children who pay better attention have better educational outcomes during their school years). However, the ability to pay attention varies across different people; the ability also varies in the same person over time. Attention lapses are common but can have negative consequences, as illustrated by the spike in car accidents in recent years caused by drivers who were distracted by their phones. Her presentation focused on how brain-based models can be used to predict attentional abilities, to capture changes in attention over time, and to characterize individual differences in working memory during development.

Functional Brain Connectivity

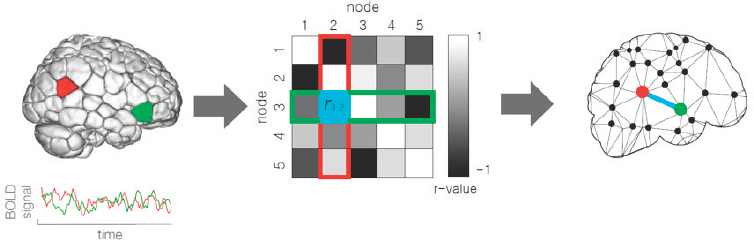

Many psychological tasks, questionnaires, and clinical measures can be used to measure differences in attention between people and within people. Rosenberg proposed that brain measures can be used to complement these behavioral measures of attention, focusing on the role of functional brain connectivity as a useful brain measure. Functional brain connectivity can be assessed through a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scan of the brain. Based on the scan, brain activity is divided into several hundred regions or nodes. Researchers can then look at the activity signal time course in one node and correlate it with a single time course in every other node, generating a whole-brain connectivity matrix or connectome. In the matrix shown in Figure 4-1, the rows and columns represent distinct brain regions; cells represent the correlation between activity in those regions. The matrix can then be projected back onto the brain. Rosenberg explained that the lines in between the nodes are statistical interactions—specifically, they are correlation coefficients—that do not necessarily represent structural connections between brain regions.

Functional connectivity is the measure being focused on because evidence suggests that every person has a unique pattern of functional brain connectivity, a “functional connectivity fingerprint,” that is relatively stable over time and contains information about cognitive abilities (Finn et al., 2015; Miranda-Dominguez et al., 2014), including fluid intelligence, which can be used to predict attention and other abilities. She emphasized that more broadly, these types of predictive modeling approaches will help to move fMRI from a science of group averages—meaning, elucidating what happens in the brain on average when people pay attention—toward a science of individual differences. This could potentially enable a single brain scan to provide specific information about an individual person’s brain, abilities, outcomes, and most appropriate treatments or

SOURCE: Adapted from figures presented by Monica Rosenberg at the workshop Brain Health Across the Life Span on September 24, 2019.

interventions. However, care must be taken to test model generalizability, to control for confounds, and to ensure that predictions are robust and meaningful.

Use of Brain-Based Models to Predict Attentional Abilities

Rosenberg described some of her laboratory’s work in using brain-based models to predict attentional abilities (Shen et al., 2017). Connectome-based predictive modeling was used to capture individual differences in sustained attention in adulthood and to capture real-world attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in a cognitively developing population (Rosenberg et al., 2016a). An overview of the process of connectome-based predictive modeling is provided in Box 4-1.

Capturing Individual Differences in Sustained Attention in Adults

To operationalize individual differences in sustained attention in adults, the researchers used a gradual-onset continuous performance task (Esterman et al., 2013). Brain imaging data were collected from 25 healthy adults while they were performing a challenging task requiring continuous, sustained attention. In addition to measures of whole-brain functional connectivity, task performance was also measured for each subject. The aim was to use the functional connectivity patterns to predict task performance using connectome-based predictive modeling (Rosenberg et al., 2016a; Shen et al., 2017).1

In this case, the expected effect would be that people who express the high-attention network more strongly overall would perform better on the task, while people who express the low-attention network more strongly would perform worse. The analysis procedure guarantees that the features are actually predicting attention, and they are not simply related to the selected measure by chance. Specifically, the investigators leave out data from a single subject and correlate the strength of every connection with behavior across the remaining subjects, generating a matrix that indicates the relationship between the strength of a functional connection and behavior across individuals. Data from the left-out person are then brought back into the model to see how strongly the person expressed the networks. This measure is used to predict how well the left-out person performed on the task. Iterating this process through all of the subjects—leaving each person out once—allows for a predicted measure of performance for each individual to be derived. Thus, how people actually performed on the task can be plotted against how they were predicted to perform, based on their connectivity patterns.

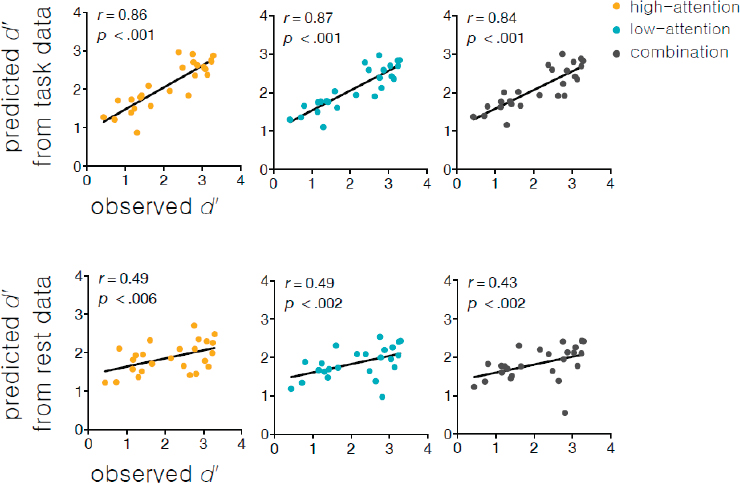

When Rosenberg’s group made predictions using the high-attention network model, they captured a significant variance in performance—more than 70 percent of the variance—in how people perform the task, based on brain data alone (Rosenberg et al., 2016a). They achieved similar performance when making predictions with the low-attention network model as well as a model that takes into account strength in both networks.2 Next, her group applied the models to data collected while participants were just resting in the scanner and not doing any task. The aim was to compare these rest predictions with the task predictions to determine whether subjects needed to perform an attention task at all in order for researchers to predict how well they pay attention, as well as

___________________

1 The code associated with this technique, visualization tools, and a detailed protocol are available online at github.com/YaleMRRC/CPM (accessed November 3, 2019).

2 They are now exploring the possibility that the high- and low-attention network models may be providing some degree of redundant information.

whether the functional architecture of attention is reflected in the brain while a person is lying in the scanner looking at a fixation cross on the screen. Rest data were also able to predict performance.

Although the predictions were not as accurate as those based on task data, her team was still able to explain significant variants in participants’ performance based only on their functional connectivity patterns observed at rest. Figure 4-2 depicts plots of the prediction from task data and from rest data. Rosenberg suggested that task predictions are better than the rest predictions because engaging in the attention task perturbs circuits relevant to sustained attention, potentially magnifying these behaviorally relevant individual differences. She likened psychological tasks to “stress tests” for certain types of processes like attention (Finn et al., 2017).

Predicting Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms in Children and Adolescents

To capture a broader concept of sustained attention, rather than focusing on predicting performance on an idiosyncratic lab-based task, the researchers applied the model to data collected in a very different

SOURCES: As presented by Monica Rosenberg at the workshop Brain Health Across the Life Span on September 24, 2019; Rosenberg et al., 2016a.

context—publicly available data3 from children and adolescents with ADHD.4 For each child, there was a resting-state functional connectivity pattern and a measure of ADHD symptoms rated by clinicians using the ADHD Rating Scale IV. Rosenberg noted that her group had scores for children that had received an ADHD diagnosis, as well as for children who did not have a diagnosis, so they were predicting continuous measures of symptom severity in both patients and controls.

The goal of this analysis was to apply the model to predict how each child or adolescent would perform if (hypothetically) given the same continuous performance task that the adults received in the laboratory (Rosenberg et al., 2017). The expected negative result emerged when Rosenberg’s group plotted the severity of ADHD symptoms on the x-axis (with higher scores indicating more frequent or more severe symptoms) and predicted task performance on the y-axis. When they predicted that a child or adolescent would perform well on the task, the subject showed fewer symptoms or less severe symptoms of ADHD. This suggests that the model is capturing something in general about the ability to sustain attention, not just something specific about performance on one laboratory-based task.

To assess whether the model was specifically predicting abilities related to attention as opposed to, for example, predicting the ability to comply with instruction and to be high functioning overall, her team analyzed whether the predictions were related to ADHD scores when controlling for intelligence quotient (IQ); the predictions were not related to IQ scores when controlling for ADHD scores. These predictions are general, in that they are generalizing across datasets and across measures of sustained attention and across age groups. However, the predictions are also specific, in that they are predicting scores specifically related to attention.

High- and Low-Attention Network Anatomies

Rosenberg explained that data-driven predictive approaches can inform the functional architecture of attention and cognition. Specifically, she presented data to illustrate the anatomy of high- and low-attention data-driven networks in the brain (Rosenberg et al., 2016a, 2017). In summary, she showed that brain regions (or nodes) can be characterized by how many connections they have in both high- and low-attention networks, and the proportion of connections in each. Together, these connections

___________________

3 The ADHD-200 Sample: http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/adhd200 (accessed February 3, 2020).

4 From the ADHD 200 dataset and data collected in China from 113 children and adolescents aged 8–13 years.

in high- and low-attention networks only represent about 4 percent of all possible functional connections in the networks. Some nodes are highly specialized in one network or the other, whereas other nodes have approximately equal numbers of connections in the network predicting better attention and the network predicting worse attention. She emphasized that when predicting differences in attention, the functional connectivity measure is particularly important—it is not the individual brain regions per se that matter, but rather the statistical interactions between the activity time courses of pairs of brain regions.

Data-driven techniques like this one can serve as hypothesis generators by suggesting regions or connections that were not previously known to be related to attention. They can also confirm previous hypotheses or agree with work in the field. For example, one feature of the low-attention network is the large number of functional connections between hemispheres of the cerebellum. This agrees with work in ADHD suggesting that cerebellar changes are particularly relevant.

Using Brain-Based Models to Capture Changes in Attention Over Time

Rosenberg turned to the use of brain-based models to capture changes in attention over time. If her laboratory’s model is related to the ability to focus, it should also change with attentional changes over time. Emerging evidence suggests that some connectome-based models are capturing changes in attention within a single person; this has been documented and suggested in the literature (Adam et al., 2015, 2018; Christoff et al., 2009; Cohen and Maunsell, 2011; deBettencourt et al., 2018; Esterman et al., 2013; Rosenberg et al., 2013; Sali et al., 2016; Smilek et al., 2010). To determine whether their model was sensitive to changes in attention over time, her team measured the same person doing the same continuous attention task while being scanned by fMRI at 30 different time points over 11 months (Salehi et al., 2020). This yielded a functional connectivity matrix and task performance assessment from each of the 30 sessions. The task performance at each session was plotted against the model’s prediction of the subject’s performance based on connectivity in every session-specific pattern. Rosenberg’s group found that the model is sensitive to the individual’s daily changes in task performance (Rosenberg et al., 2020). If the model was only sensitive to the person’s average attentional ability, no relationships between changes in this connectivity signature of attention and changes in behavior would be expected, but the model was actually sensitive to the person’s best session and worst session. It was also very accurate in capturing the person’s overall general average sustained attention ability in addition to capturing changes in attention from session to session.

Use of Brain-Based Models to Capture Changes in Attention Caused by Pharmacological Interaction

Rosenberg noted that daily or moment-to-moment fluctuations in attention are commonplace, but attention also changes with pharmacological intervention. She presented data from a study in which healthy adults were given either a single dose of methylphenidate or no drug at all (Farr et al., 2014a,b; Rosenberg et al., 2016b). Methylphenidate is a common ADHD treatment that blocks dopamine and/or epinephrine reuptake (Berridge et al., 2006; Spencer et al., 2015; Volkow et al., 2001). It is very effective, providing symptom improvement in about 70 percent of patients with ADHD (Greenhill et al., 2002); performance enhancements are also seen even in participants who are not diagnosed with ADHD. Investigators examined high- and low-attention network strength in a group of adults given a single dose of methylphenidate before the scan—as expected, individuals given the attention-enhancing drug showed functional connectivity signatures of better attention. That is, participants who had been administered methylphenidate showed higher high-attention network strength and lower low-attention network strength than control participants who received no medication. This indicates that methylphenidate is not just having an effect on a person’s functional connectivity overall; rather, it is selectively modulating the functional connections related to attentional abilities. The same pattern was observed both when people were performing a stop-signal task and when they were simply resting. This set of studies suggests that the same models that predict individual differences in attention are also capturing fluctuations in attention within people over time, as well as changes in attention resulting from pharmacological interventions.

Beyond characterizing individual differences in sustained attention, these functional connectivity patterns and predictive modeling methods can also be used to capture individual differences in a number of different abilities, behaviors, or clinical symptoms (Shen et al., 2017). For instance, these patterns can be used to predict aspects of adult working-memory function (Avery et al., 2020), adult fluid intelligence (Finn et al., 2015), and autism symptoms (Lake et al., 2019). Work is ongoing across many research groups to share and validate functional connectivity biomarkers and evaluate the degree to which they generalize across datasets. “If we really want to move toward an individualized translational neuroscience and applications, we need to confirm that our models generalize beyond the single dataset on which they are built,” Rosenberg noted.

Use of Brain-Based Models to Characterize Working Memory in Development

Rosenberg explained how a different type of brain measure and brain-based predictive model is being used to characterize working memory in developmental periods such as childhood and adolescence. Working memory is a critical cognitive ability related to processing speed, fluid intelligence, and attention that allows a person to store and manipulate information in the mind (Baddeley, 1992; Kane and Engle, 2002). Like attention, working memory varies significantly between individuals and changes across development (Klingberg et al., 2002). Previous work suggests that these differences are supported by frontoparietal circuitry in the brain (Darki and Klingberg, 2015; Klingberg et al., 2002; Palva et al., 2010; Satterthwaite et al., 2013). Mental disorders, including ADHD, anxiety and mood disorders, schizophrenia, and substance abuse, tend to emerge and peak during adolescence (Lee et al., 2014). The ability to predict symptoms and abilities earlier in development (prior to adulthood) could offer greater opportunities to intervene earlier and to afford people improved outcomes.

Relationships Between Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Activity and Working Memory

To that end, initiatives like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study (ABCD) are collecting and sharing large developmental datasets with MRI data, as well as providing resources to train and test predictive models (Rosenberg et al., 2018). Rosenberg described the results of one project that used data from the first release of ABCD data (including more than 5,000 children aged 9–10 years collected at 21 sites across the United States) to characterize individual differences in working memory. Activation in frontoparietal regions during a challenging working-memory task (e.g., a two-back task)5 relative to a lower-load working-memory task (e.g., a zero-back task), was significantly related to out-of-scanner working-memory performance (Rosenberg et al., 2019). This indicates that children who have stronger working-memory abilities tend to have greater activation in the frontoparietal regions during a working-memory challenge than children with less strong abilities.

Such differences are not seen with brain activation in other contexts, such as activation during emotional versus neutral face blocks of the emotional n-back task. Similarly, no differences were observed in data

___________________

5 A task in which participants are presented several stimuli in a row, and then asked to determine whether the current stimulus is the same as a stimulus shown two steps earlier.

collected during an inhibitory control task (stop-signal task) or a reward processing task (monetary incentive delay task). This suggests that 9- and 10-year-olds with stronger working memories do not simply have greater engagement of frontoparietal circuitry overall in any challenging context. Rosenberg reiterated that psychological tasks can be thought of as stress tests for elucidating individual differences in brain activity related to behavior. Brain-related differences are observed in children with stronger and weaker working memories when they are given an explicit working-memory challenge but not in the other contexts tested.

Discussion

Huda Akil, codirector and research professor of the Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute and Quarton Professor of Neurosciences at the University of Michigan, asked for clarification about how it was possible to pick up changes in sustained attention over time and with treatment, given the lack of sufficient continuity to make predictions without the person actually doing the task. She also asked whether sustained attention is best conceptualized as a trait, a state, or a combination of both. Rosenberg replied that the analysis shows that it is possible to capture differences from day to day in a single person as well as to capture the person’s mean or average of attentional focus in a variety of contexts. Factors like motivation, context, sleep, and caffeine all influence whether the person will achieve the maximum or minimum level of focus that fluctuates around that day-to-day average. The models seem to be picking up that type of average mean ability, but they are also sensitive to changes.

Work is ongoing to collect more data on single individuals, in addition to high-throughput big data samples, which should help to tease apart these state-like versus trait-like effects. Evidence suggests that this functional connectivity fingerprint is relatively stable across development and over time, but it can be altered to some degree by task states, cognitive states, and pharmacological states. Akil added that this raises ethical questions related to publicly available brain signatures.

Martha Snyder Taggart, science writer and staff member at BrightFocus Health, asked Rosenberg if her team had observed any subjects with cross-correlated thinking types, such as creativity, who may have more tendencies to integrate against attention. Rosenberg replied that they have not looked at the relationship between those types of factors and attention, but they have investigated the relationship between functional connectivity in general with personality traits and creativity. Her team found that connectivity patterns predicted people’s divergent thinking abilities, which have been generalized across multiple independent

datasets collected across various continents. Work from other laboratories has suggested that other patterns predict aspects of personality.

A participant asked if the relationship between circadian rhythms and attention or reaction times has been explored. Rosenberg responded that her lab has not studied it directly, but they have found that their predictions are not related to time of day. However, attention can fluctuate minute by minute and hour by hour, so it could be informative to capture data from an individual at multiple time points in a specific day. Another participant remarked that people who are depressed or lonely tend to pay attention to the negative, such as being hypervigilant to social threats. Rosenberg noted that sustained attention is not always a positive quality—it is important to pay attention, but not to the extent that it prevents response to other cues in the environment. Going forward, it will be important to characterize the brain signatures of different types of attention without assuming that “more is always better.”

ROLE OF MEDITATION IN IMPROVING BRAIN HEALTH AND RESILIENCE

Elizabeth Hoge discussed brain health and resilience in the context of research on meditation, a practice that is becoming increasingly popular and which is thought to confer health benefits. Her presentation was framed around how meditation training may improve brain health and resilience, with a focus on potential biological changes that may be detected as a result of meditation training.

Effect of Meditation on Brain Structure

Hoge described cross-sectional research efforts to measure the effects of meditation using structural MRI to evaluate the density of brain matter in the cortex of meditators (Lazar et al., 2005). The study included 20 experienced meditators with an average of 9 years of daily meditation practice and 15 nonmeditating controls matched on age, sex, race, and education. The structural MRI showed several areas of significantly increased cortical thickness in the meditators compared to the controls.

Specifically, the brain areas of higher density in meditators were the insula and the prefrontal cortex. The insula is associated with interoception—or increased awareness of the body—which is in keeping with the aim of many meditation practices of paying attention to what is happening in the body. The insula is associated with the integration of sensory and emotional information as well as empathy and compassion; this area is also more active during compassion meditation (Lutz et al., 2008). The insula tends to be abnormal in people who have brain pathologies, Hoge

added. For instance, the insula tends to be smaller in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. The prefrontal cortex is associated with working memory, executive function, selective attention, and fluid intelligence. Plotting the age of the study participants revealed that control subjects had a standard decline in cortical thickness that would be expected with aging; however, the meditators did not show that decline. The research group postulated that meditation may help to slow normal aging through some type of protective effect or enhancement of resilience.

Another study looked at experienced yoga practitioners, meditators, and controls (Gard et al., 2014). The subjects’ fluid intelligence was measured by Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices. When the subjects’ fluid intelligence was plotted against their ages, the typical decline of fluid intelligence with increased age was seen in the control subjects, with less decline among the meditators and experienced yoga practitioners. These studies suggest that there is a protective element to these practices, said Hoge. She noted that this is aligned with the ethos of the meditation tradition, which is designed to see reality more clearly and therefore help humans reach happiness and joy.

Effect of Meditation on Resilience

Next, Hoge presented evidence related to the effect of meditation on resilience. The dictionary defines resilience as the ability to return to original shape after being stretched, pressed, bent, and so on, as well as recovering from and adjusting well to misfortune or change. In psychology, the concept of resilience refers to the ability of most people, when exposed even to extraordinary levels of stress and trauma, to maintain normal psychological and physical functioning and avoid serious mental illness (Russo et al., 2012).

Measuring Resilience in Humans

Several strategies can be used to measure resilience in humans: (1) examining people who have experienced adversity, stress, or trauma and then function well later; (2) bringing people into the laboratory, stressing them, and then measuring their ability to cope; or (3) administering self-report questionnaires. The third strategy is the most commonly used to measure resilience in the available literature. Hoge carried out an informal analysis of the most recent 20 articles in PubMed on human psychological resilience. Only one-quarter of the subjects measured resilience in terms of mental or physical health outcomes after adversity; three-quarters measured resilience using pencil-and-paper self-report questionnaires. This is a concern, she said, because the latter strategy has never been validated

against behavioral resilience as measured by the first or second strategies. Thus, it is not clear what this most common strategy is actually measuring.

These questionnaires, which typically are based on resilience scales constructed by psychometricians, are often used to evaluate the putative and vaguely defined construct of resilience related to the outcome of behavioral or pharmacological interventions. For example, one study concluded that treatment with tiagabine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and cognitive behavioral therapy improves resilience as measured by a self-administered questionnaire (Davidson et al., 2005). This underscores the problems related to measurement and reporting of resilience and the need to move the field toward validating these commonly used pencil-and-paper measures against some kind of behavioral measure.

Effect of Mindfulness Meditation on Resilience

Hoge’s laboratory carried out a study to assess the effect of mindfulness meditation practice on resilience. Beyond merely measuring resilience, the aim was to determine if the meditation practice actually improves a person’s ability to cope in the face of adversity. Mindfulness meditation is a form of meditation with a focus on self-regulating one’s attention—meaning, maintaining focus on the immediate experience of sensations, emotions, and thoughts in the present moment—and on adopting a particular orientation toward one’s experiences in the present moment, which is characterized by curiosity, openness, and acceptance (Bishop et al., 2004).

Specifically, the researchers were interested in exploring the effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction in people with generalized anxiety disorder (Hoge et al., 2013a). See Box 4-2 for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for this disorder. The study design randomized about 90 participants either to a mindfulness-based stress reduction class or to an attention control group that received stress management education, which was an exact match for time, attention, and other variables in order to reduce expectancy bias and social effects in the meditation group. The outcome measures included (1) clinical anxiety symptoms; (2) acute stress measures during a laboratory stress task, including the self-reported State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and endocrine measures; and (3) neuroimaging findings during an emotional face task. The researchers chose to measure resilience in terms of emotional reactivity to stress in a laboratory setting using the Trier Social Stress Test.6 Participants completed the Trier Social

___________________

6 The Trier Social Stress Test uses public speaking to induce stress in study participants by asking them to deliver an impromptu 8-minute speech in front of an audience of “evalu-

Stress Test twice, once prior to any intervention and 10 weeks later after the intervention.

Hoge reported that the meditation group had a significantly greater decrease in their STAI anxiety scores during their speech compared to the control group. Because they reported having less anxiety during the second test, it could mean that they are more resilient to stress after the mindfulness-based stress reduction class. Both before and after the intervention, participants also completed a questionnaire composed of self-statements during public speaking; they were asked the extent to which they agreed with different positive and negative statements about their speeches during the Trier test7 (Hofmann and Dibartolo, 2000). After the intervention, people in the meditation group had a greater decrease in negative self-statements, although it was not statistically significant. However, there was a significant increase in the positive self-statements among the meditation group compared to the controls, despite the fact that the meditation training did not specifically teach participants to encourage themselves and did not contain any training in how to deal with the speech task. She surmised that this finding suggests that there

___________________

ators” wearing white lab coats. The test also includes a surprise arithmetic task that is assessed in real time by the evaluators.

7 Example negative statements: “I’m a loser”; “A failure in this situation would be more proof of my incapacity.” Example positive statements: “I can handle everything”; “This is an awkward situation but I can handle it.”

is a potential component of resilience that might be described as treating oneself with more kindness or with more self-regard.

The researchers looked at changes in the levels of stress hormones in the two groups before and after the training intervention. They focused on the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) because it comes from the brain, unlike cortisol, and has a much shorter half-life that allows for greater temporal specificity. They assessed the two groups’ differences in ACTH levels in response to the Trier test administered prior to and after the intervention. People in the meditation group had a statistically significant decreased overall ACTH response compared to the people in the control group, indicating that this group had decreases in stress hormones in addition to decreases in self-reported stress after mindfulness-based stress reduction training.

Effect of Mindfulness Training on the Biology of the Brain

Hoge’s research group has also looked at the longitudinal changes in the brains of people who have been taught how to meditate in order to assess which of those neural changes may underlie clinical benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction in people with generalized anxiety disorder (Hölzel et al., 2013). The study was based on existing knowledge about generalized anxiety disorder (Maslowsky et al., 2010; Mennin et al., 2002, 2005). People with this disorder tend to have low emotion regulation ability, as manifested in more negative reactivity and poorer understanding of emotion. However, psychotherapy can improve emotion regulation ability, which is thought to result from the involvement of the prefrontal cortex when the amygdala is hyperreactive.

Study participants with generalized anxiety disorder were randomized to receive either mindfulness-based stress reduction or the control training. Before and after the intervention, participants completed an fMRI affect labeling task by making a determination about the emotion being presented in photographs with subjects displaying different facial expressions. The participants’ fMRI responses to neutral facial expressions was of particular interest, because people with anxiety disorders tend to focus on and worry about the meaning of neutral or ambiguous information. The investigators carried out a functional connectivity analysis of the participants to measure the extent to which different brain regions coactivate, using the right amygdala as a seed.

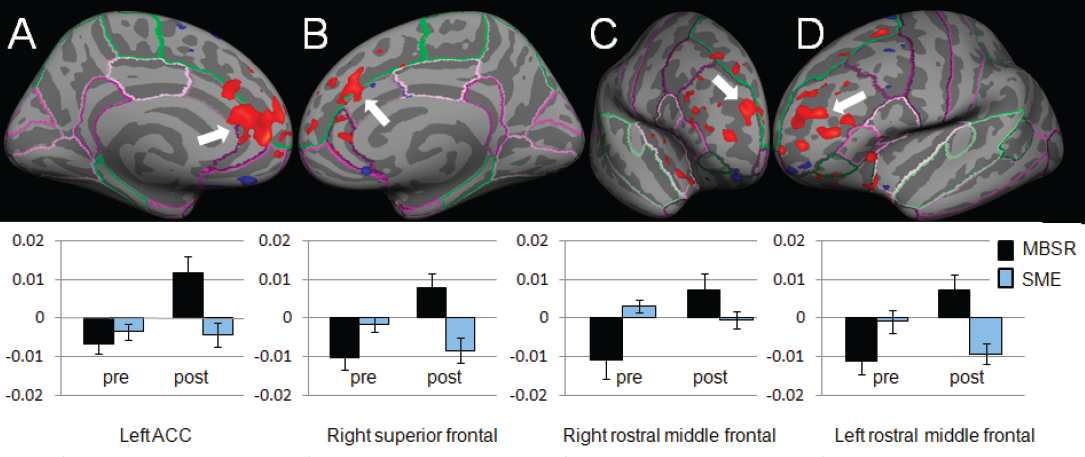

Figure 4-3 illustrates how the changes that occurred as a result of the training were significantly different in the meditation group compared to the control group.

Panel B depicts the right superior frontal area, which is associated with social exclusion, social pain, and pain catastrophizing. Panel A

NOTE: ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; MBSR = mindfulness-based stress reduction; SME = stress management education.

SOURCES: As presented by Elizabeth Hoge at the workshop Brain Health Across the Life Span on September 24, 2019; adapted from Hölzel et al., 2013.

shows the significant changes in the anterior cingulate cortex, which forms part of the salience network with the insula; this subgenual part of the anterior cingulate cortex is associated with emotional regulation and affective tasks. Panels C and D show the prefrontal cortex areas. Panel C indicates that the same area of the cortex is associated with two different—but perhaps related—phenomena: it was involved when people with generalized anxiety disorders learned meditation, and was also found to be of greater thickness in experienced meditators. Next, investigators correlated the participants’ Beck Anxiety Inventory scores after the intervention with their functional connectivity to evaluate the effect of these observed changes on clinical anxiety symptoms.

Effect of Meditation on Longevity

Hoge concluded by describing her group’s work using longevity as a measure for overall health by looking at telomere length in experienced meditators (Hoge et al., 2013b). Telomeres are caps at the ends of chromosomes that protect the tip of a chromosome from deterioration. They shorten with each replication and shorten predictably with age. According to cross-sectional data, telomere shortening appears to be accelerated in populations that experience increased psychological stress, such as mothers caring for a chronically ill child (Epel et al., 2004) or daughters of depressed mothers (Gotlib et al., 2015). The researchers predicted that longer telomeres would be observed in people who meditate if meditation is indeed protective, especially if they practice loving-kindness meditation. The study design was based on the presumption that being kind toward others can improve a person’s overall health.

Other-focused activities such as community volunteering (Oman et al., 1999) and spousal caregiving (Brown et al., 2009) can sometimes improve health. Forgiveness of others is associated with greater longevity (Toussaint et al., 2012), and people with high hostility levels have a higher risk of mortality (Smith et al., 2004). The researchers recruited long-term meditators with experience in a type of meditation called loving-kindness meditation, or Metta, as well as controls matched on any factor that could affect telomeres. As expected, the loving-kindness meditators had longer telomeres than their age- and gender-matched controls. Overall, this difference was not significant. However, when broken down by gender, loving-kindness meditators who were women had significantly longer telomeres than their age-matched controls.

Discussion

Colleen McClung, professor of psychiatry and clinical and translational science at the University of Pittsburgh, asked if study participants with anxiety ever report that mindfulness is counterproductively more stressful for them. Hoge said that in a clinical setting, meditation teachers specifically address this issue, which tends to help prevent catastrophizing types of thought cycles in the participants. However, some patients with posttraumatic stress disorder who experience flashbacks need to have exposure therapy first before learning how to meditate.

It has been suggested that it is the luxury of having quiet time to oneself that makes meditation and mindfulness beneficial for some people, McClung added. The data suggest that more is happening in meditation than time to oneself, said Hoge. In her study, people in the control group were also given audio tapes to listen to during their time to themselves that were unrelated to meditation. She suggested that there are active mechanisms specific to meditation that have to do with positive self-regard or being nonjudgmental, for instance. A participant asked Hoge to elaborate on dose response in the context of meditation (e.g., differences related to the length of experience meditating or the frequency of meditation). Hoge said that a significant dose–response relationship has not yet been established in the literature.

Akil commented about the use of the Trier Social Stress Test as described in Hoge’s studies. Akil’s group ran a study that looked at the effect of emotion on memory. Participants included people with depression, people with anxiety and depression, and healthy controls. They administered the Trier Social Stress Test and measured neuroendocrine markers, including ACTH, then did a follow-up study 1 or 2 weeks later to ask participants what they remembered about the experience. The participants with depression had better recall about their perceived failures in the arithmetic task, even though the group’s actual error rate was no different—and in some cases even better—than the control group, who hardly remembered the test at all.

After this study, Akil stopped administering the Trier test in people with depression because of its traumatizing effect. She added that the ACTH response was not predictive in the group with depression, who tended to walk into the test with very high glucocorticoid levels because they were anticipating nervousness. Consequently, they tended to manifest a flat stress response instead of the solid response observed in controls. Harkening back to the distinction between good stress and bad stress, she noted that a solid stress response that starts and ends swiftly is preferable to a “floppy” response that never really ends, as is common among people with anxiety. In the context of defining resilience, she added, it is important to consider how long a negative reaction persists.

She suggested that memory of positive versus negative experiences could be used as one potential measure of resilience.

PANEL DISCUSSION ON BEHAVIORAL AND BIOLOGICAL CONVERGENCE

Akil opened the discussion by asking panelists how they would define resilience based on their own research. Hoge replied that resilience relates to the capacity to cope with stress. A person experiencing bad stress may feel overwhelmed and lacking in the resources to cope, while a person experiencing good stress believes they have the resources to cope with it. Resilience could thus be defined by a person’s belief in his or her ability to cope and succeed in the face of stress without negative mental or physical health outcomes. Within this paradigm, it could be useful to help people transform bad stress into good stress so they feel more confident and capable without being preoccupied by their past mistakes. Rosenberg suggested thinking about resilience as it changes over time, because it seems to involve dynamic processing to “bounce back” after a challenging situation.

The most difficult step in research on the brain and cognitive processes is to identify whether a given brain phenomenon is a risk factor or a response, said Damien Fair, associate professor of behavioral neuroscience, associate professor of psychiatry, and associate scientist at the Advanced Imaging Research Center at the Oregon Health & Science University. Differentiating between the two, while challenging, is critical for characterizing the brain’s response to stress and how to manage it to improve long-term outcomes.

Gagan Wig, associate professor of behavioral and brain sciences at the Center for Vital Longevity at the University of Texas at Dallas, remarked that it might be useful to frame the discussion by considering a potential distinction between emotional and cognitive resilience. Cognitive resilience could be described as a system that is perturbed by some life event, but the system is still able to function on a longer time scale. In other words, cognitive resilience amounts to neurodegeneration that does not result in a major collapse of cognitive abilities, as opposed to organic damage of some kind.

It would be interesting to explore the extent to which different types of resilience are separable and how they feed into each other, said Akil. This could help inform strategies to help people with a low capacity for one type of resilience and a strong capacity for the other to use one to strengthen the other, possibly through cognitive therapy. When people’s cognitive abilities decrease with age, for example, they may call on other neural circuitry to help with a declining function such as memory. She

asked whether other types of capabilities could be called into action to compensate for or complement other types. Fair suggested that brain resilience is another distinction. The brain has the capacity to change as a function of various kinds of inputs; finding ways to measure that type of resilience would allow for better understanding of the capacity of the brain to be resilient in different contexts.

With regard to breaking out multiple types of resilience, Lis Nielsen, chief of the Individual Behavioral Processes Branch of the Division of Behavioral and Social Research at the National Institute on Aging, remarked that resilience is not limited to a particular part of the brain or physiology. It is likely that the brain has multiple capacities and systems that are related to resilience. She was concerned that striving for a single unifying definition of resilience—in the service of identifying specific measurable psychological capacities—could occlude the idea that resilience constitutes multiple capacities that interact with each other. Akil remarked that gene expression profiling over multiple brain regions in people with severe depression reveals a host of changes all throughout the brain—not just in one place. In those brains, the correlation of gene expression between regions has completely shifted, connections between reward circuits in the prefrontal cortex are altered, the balance of brain circuits has become tilted, and there is degradation of the support system at the biological level. When the symptoms of a brain disorder are this severe, it can be difficult to distinguish between affective, cognitive, attentional, and memory symptoms.

Akil suggested that understanding more about the sequence of events that lead to severe brain disorders could help to elucidate critical points of intervention. This knowledge could also shed light on integrative ways to help balance brain capacities that are undermined with brain capacities that are stronger. This underscores the idea that no single pattern of brain phenotypes or behavioral phenotypes can be used to achieve a healthy outcome or a healthy life, said Rosenberg (Holmes and Patrick, 2018). Instead, there are probably ways in which each person’s phenotypes are more and less optimal, but they can operate together to produce good outcomes—there is a diversity of ways to achieve a healthy brain.

Self-Report as a Measure of Resilience

Nielsen noted that although the scales that measure resilience are not necessarily well validated with real outcomes, self-report measures may be more suitable for assessing certain outcomes of resilient processing in response to an imposed stressor. For example, using experience sampling approaches to capture self-reported emotion over time—in parallel with measures that capture fluctuations in hormone levels or behavior—may

offer insights about how people “bounce back” from a stressor or challenge. This is more informative than the scale-based self-reports that are widely used. Rosenberg commented that a component of resilience—how a person feels about their own abilities to handle a stressful situation—might only be measurable via self-report. Self-report scales are confounded by social desirability, noted Hoge, which can make a person’s self-report inconsistent with how the person actually acted in a situation.

Brain Imaging Signatures of Attention

Akil asked Rosenberg if the “healthy” style of attention has a particular brain imaging signature. She replied that there is no single signature for attention overall, nor is there a single ideal marker of the best kind of attention in every context. Rather, attention is composed of multiple different processes. Each person may have an attention vector, with a number of different overlapping networks—or perhaps even distinct networks—that predict different attentional processes (e.g., sustained attention, spatial orienting, alerting, executive control). Thus, each person has a different pattern of abilities and of functional networks related to those abilities. No single pattern is necessarily best in all contexts, so attention needs to be adjusted and deployed in a context-dependent way. For instance, the attentional demands of sitting in a lecture are very different than the attentional demands of navigating a dark forest at night. Being able to flexibly deploy attention is a skill in and of itself, Rosenberg added, so it is not always the case that there is one ideal marker of the best kind of attention in every context.

Self-Awareness of Resilience and Other Brain Processes

Stephanie Cacioppo, director of the brain dynamics laboratory, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience, and assistant professor at the Grossman Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, asked other participants if people need to be aware that they are resilient in order to be resilient—meaning, have meta-awareness of their own resilience. In Cacioppo’s brain dynamics studies, they have explored brain signatures of self-awareness. Cacioppo’s team uses high-density electroencephalography (EEG) to measure how fast a person detects negative information or positive information. If the subject is lonely, within 200 milliseconds their brain will detect the difference between a threat and a positive event, but self-report questionnaires show that they are not aware that they have detected it. Hoge suggested that people who are resilient would generally be aware of it, and they would be able to self-report less stress in the face of a challenge

or adversity. Fair said that people are not aware or cognizant of those types of dynamics in their own brains.

Akil remarked that brain measures could play an important role in gathering evidence of what is happening in the brain—beyond a person’s awareness or consciousness—that could inform our understanding of our own health, vulnerability, and resilience toward achieving better well-being. She asked, “What are we missing, if we only look at behavior and not look at the brain?” Rosenberg noted that people are not always aware of their own attention lapses, but they can be detected with fMRI. The emerging field of real-time neurofeedback detects patterns in the brain related to certain processes and provides feedback to the person about that activity. Initial evidence suggests that this may be more effective than some behavioral interventions, she added (deBettencourt et al., 2015). The Western-style concept of brain function is very top down, noted Akil, but more Eastern philosophies, including meditation, have a more bottom-up way of looking at affective and cognitive control that is very autonomic, but also relates to immune function and peripheral input. She urged participants not to restrict their thinking to achieving resilience through conscious cognitive mechanisms.

Hoge replied that this is important to bear in mind, because people are not always able to articulate what they have experienced or why they experience life differently after doing meditation training. Brain imaging suggests that feelings are not being suppressed; instead, there was more connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Akil also highlighted the interaction between the cognitive and the affective—“Do we feel differently when we think differently, or do we think differently when we feel differently?” Rosenberg suggested that an interesting approach would be to try to predict individual differences in emotional processing or emotional resilience, to explore whether there are networks that predict those processes, and, if so, to look at the degree to which they overlap with networks involved in cognitive and attentional processes.

Measuring Resilience

Akil asked the panelists to comment on executive function—or the ability to “shift gears”—in terms of resilience. It will be important, albeit challenging, to measure the brain’s capacity for resilience, particularly in response to a given input or some genetic risk factor, said Fair. Rosenberg suggested a longitudinal approach: using a brain measure at baseline to predict an expected resilience outcome. Hoge was concerned that such an approach would not capture the “bouncing back” aspect of resilience, because it would measure a person’s response in the face of a stressor, rather than the person’s ability to recover.

Gender Differences in Brain Disorders

Recent studies have shown that men and women with depression have almost opposite signatures in their brain, with different gene expression changes occurring in very different directions, said McClung. It also appears as if the inflammatory processes of depression mainly occur in men and not necessarily in women, suggesting that there may be sex-based differences in brain disorders to be explored further. Hoge noted that a very persistent finding in meditation treatment research is that it has a bigger effect in women, although it is not clear why. Akil said that an important research question is to better understand the sex or other types of individual differences in the effect of brain diseases, in resilience, in coping styles, and in different affective patterns, cognitive patterns, and attentional patterns. Ideally, the results would coalesce to reveal different “brain neurotypes” with respective features, characteristics, and functions. Certain neurotypes might make a person more responsive to meditation or to attention shifting in other ways, for example. A major challenge, however, will be to unpack the heterogeneity in a way that is positive and does not fall back on prescriptive labeling that could potentially be damaging. Better biological markers would be helpful in reframing research questions to help people improve their resilience and well-being, Hoge added.

This page intentionally left blank.