Direct engagement with the community is beneficial for anyone involved in health care, from health professions students to health care executives. As an illustration of the importance of community-based experiences, David Benton, chief executive officer (CEO) of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, shared a story about working in the East End of London. The people in this community, which is an area of huge ethnic and linguistic diversity, faced a number of challenges when trying to access emergency medical care. The CEO at Benton’s health care organization was having a difficult time understanding and addressing these challenges. With the cooperation of community members, Benton took the CEO out into the neighborhood to meet with local people from several different ethnic groups. After his experiences in the community, the CEO said that it was frustrating not being able to understand what people were saying or what was happening. Benton used the CEO’s frustration to make a point:

I said, “Just think about it. You went to visit these communities voluntarily. You are mentally healthy, as well as any of us are, and you found it incredibly stressful and frustrating. Just imagine what it would be like if your wife, your child, was coming into the accident emergency department and you were not able to communicate some of those issues.”

Benton said that this experience was life changing for the CEO, and it made him realize the efforts that needed to be made to better serve their diverse communities.

Experiential learning—in which students and faculty engage and interact with community members as teachers—is essential for learning about the social determinants and about a health professional’s role in addressing them in practice. Zohray Talib, senior associate dean for academic affairs and chair of medical education at the California University of Science and Medicine, opened the session on bringing education to life in and out of the classroom by describing what experiential learning entails. Experiential

learning requires a community that is ready and receptive to building partnerships, students who are engaged and motivated to make a difference, and faculty who are committed to doing the hard work to bring communities and students together. Following Talib’s opening remarks, workshop participants heard from speakers representing academia, education, and the community. The speakers talked about how to create and improve community-engaged experiential learning opportunities, each from their unique perspective.

COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVE

Love Mouity moved to Syracuse, New York, as a refugee from Congo-Brazzaville in 2007. He now works as a coordinator for refugee outreach for the Catholic Charities of Onondaga County and also co-teaches an interprofessional class at Syracuse University on refugee health. When Mouity and his brothers first came to the United States, they worked in factories despite coming from an upper class, educated background in their home country. Mouity said that going from a “prestigious life to nothing” was very difficult and that he now seeks to be a role model for other refugees who are going through the same process. The work he does at Catholic Charities helps refugees with multiple issues, including mental health, adjusting to their new surroundings, dealing with culture shock, and becoming self-sufficient. Working with refugees, he said, requires compassion, honesty, and a “mentality of tabula rasa.” He explained that it is critical to listen to new refugees and their stories, rather than to assume that their stories are all the same. It can be difficult for refugees to open up about their past, so people working with them must take the time to gain trust in order to build a relationship of mutual honesty and openness. Mouity and his colleagues seek to make sure that the refugees who they help can in turn help others who come after them. Their guiding philosophy, said Mouity, is “ubuntu,” which is a South African idea that humans are all interdependent with each other and share a universal bond of humanity.

Timothy “Noble” Jennnings-Bey is CEO of Street Addictions Institute Inc. and director for the trauma response team, which responds to shootings and homicides in Syracuse, New York. Jennings-Bey grew up in Syracuse in a low-income, violent neighborhood, and now serves as a leader in his community and works closely with academics and students at Syracuse University. Jennings-Bey spoke about what it takes to build bridges between the world of academia and the community. He started with a story about a conversation with Sandra Lane, professor of public health and anthropology at Syracuse University. One day, Lane told Jennings-Bey that she did not know a single person who had been murdered. This was foreign to Jennings-Bey, who knows more than 150 people who have been murdered. The only way

to connect these two parallel universes, Jennings-Bey said, was in a space of empathy. By working to create an intentional, empathetic relationship, both sides can openly communicate and heal from traumas.

Two-Way Street

Jennings-Bey said that the term “cultural competence” is often used as if it is a one-way street in which students and academics learn about the culture of the community and seek to understand it. However, he said, in his opinion cultural competence is a two-way street in which people on both sides share their cultures and their stories and create a strong relationship. Jennings-Bey said that students sometimes have been told that they cannot possibly understand a community that is so different from their own, but he believes that if people humanize each other, they can understand each other. He stressed that “everybody has their own experiences” and that by sharing these experiences and perspectives, they can build relationships.

Intentionality and Sincerity

When building relationships between academia and communities, it is critical that faculty members be intentional and sincere, Jennings-Bey said. Communities, he said, can sense if an academic is “trying to meet a quota” or check the boxes for community engagement. Rather than being told what to do, community members need the spaces and the opportunity to carry on a dialogue and to solve their own problems. Mouity concurred, saying that “the intention has to be real, not just superficial” and that both sides need to have a willingness to find solutions together. Lane added that academics “have to put the time in” to create relationships that will benefit both the community and the educational institution. She said that while there is a lot of interest in replicating the partnership that has been built between Syracuse University and the community, faculty members do not want to “leave the ivory tower and find parking.” It is not enough, Lane said, to simply drop students off at a community organization; faculty members need to make efforts to intentionally get to know community members. In her case, Lane said, these efforts included sharing food with people, inviting people to her home, and attending important family events. Once these relationships have been built, she said, it is a natural next step to work together on issues of community concern.

Jennings-Bey added further context to Lane’s remark saying that Sandy’s bridge between the community and academia has allowed him to provide a different narrative of the trauma in the community, to publish academic papers on his unique theory about street addiction, and to serve as a role

model for young people in the community. He said that his journey allows young people to see a potential path forward, one where they can “articulate the pain of the people” and “help generations that come behind us.” Jennings-Bey said that he deals with “miracles” every day, such as when mothers who have lost their children to street violence turn around and help other mothers through the same thing. The relationship that Jennings-Bey has forged with students and academics from Syracuse University allows him to convey and communicate this trauma, grit, resilience, and healing power of his community.

STUDENT PERSPECTIVE

To provide further guidance to educators, three health professions students from local colleges described firsthand experiences they had had in and with communities and offered perspectives on the education they received from those experiences. First, each student offered details about the classes that they had found particularly interesting and useful. Molly Vencel, a junior studying global health at the Georgetown University School of Nursing and Health Studies, spoke about two formative classes she has taken. The first was cultural psychology, which involved students conducting in-depth ethnographic interviews with strangers who were from a different culture than the students. During classroom discussions, the students examined their own cultural biases and looked at appropriate ways to conduct research in the community. Vencel echoed Jennings-Bey’s statement that community engagement is a two-way street; she said that the time she spent sitting down with the woman she interviewed involved reflecting on her own cultural experiences as much as her subject’s. The second formative course, she said, was global mental health, for which the professor brought in speakers with unique perspectives and duties, ranging from doulas to trauma response teams. Vencel said that learning about mental health from such a broad array of speakers gave her a wider perspective on mental health and the multiple opportunities that exist for prevention and intervention along the lifespan. Her experiences in these classes led her to pursue a summer internship at the Indiana State Department of Health, working in a community outreach program for mothers.

Nigel Walker, who is in the last semester of his master’s of health administration and hospital management at George Mason University, told workshop participants that his education on social determinants has focused primarily on the fact that these factors are traditionally outside of hospital or health system control. As a student focusing on hospital management, Walker has learned that even “the best strategy, the best plan, the best facilities” cannot address all of the issues that determine a person’s health. For example, Walker said he took a health economics class that

taught that people have finite resources and make rational decisions about their use of those resources. This class discussed the fact that if a person lives in a food desert and does not have easy access to transportation, he or she may not choose to spend the time and money necessary to travel to buy healthier foods. Lessons like this, Walker said, emphasize that while hospitals have a role to play in keeping people healthy, the hospital approach alone is “not going to work.”

Meghan Hamlin, an accelerated nursing student at the Marymount University School of Health Professions, took a health promotion class that focused on the social determinants of health and health disparities and inequities. The class specifically looked at ways that nurses can affect change by working with and educating patients on actions they could take that could lessen the impact of the determinants of health. This class, Hamlin said, was particularly useful because it helped her apply classroom lessons to real-life practice. Hamlin volunteers for an organization called Remote Area Medical, which provides free medical care to those living in remote geographic locations. This class prepared her, she said, to look at upstream causes and downstream effects, make connections between patients’ lives and their health issues, and work with other disciplines at the clinics to help patients.

Hands-on Classes

The students offered their opinions on how to improve health professions education to better incorporate the social determinants of health (SDH) and community engagement. All agreed that community- and project-based classes were preferable to traditional classes that are reading and writing focused. Hamlin said that the hands-on experience makes education “more tangible” and easier to hold onto over the long term. Vencel agreed but said that as a freshman, she likely would have chosen a traditional class out of “fear of the time commitments and the emotional investments” of doing community-based work. She said a good approach may be to give students small tastes of hands-on work in a variety of introductory classes and then allow them to choose more in-depth, community-based work in subsequent classes. Vencel added that not all students are passionate about the same things, so schools should offer varying levels of engagement and the ability to choose projects that meet students’ interests.

Real-Life Relationships

The students all emphasized the importance of working with communities and organizations, forming real-life relationships, and having the opportunity to continue these relationships after the project or the

class ends. Vencel said that after being highly engaged with community organizations for a semester, she felt like she was “left hanging” after the semester ended, and she would have appreciated “more concrete ways of continuing to engage in the projects.” Walker agreed, saying that he would like the opportunity to conduct strategic planning with organizations and to have regular follow-up and continued work with the same organization. For example, he said, rather than just creating a strategic plan and “walking away,” students and organizations could build on strategies created in previous semesters or by previous students. Hamlin agreed with the need for more practice in real-life situations, saying that actively applying lessons during school—such as how to build relationships with patients—will help prepare her to apply these skills when entering practice.

Interprofessional Education

Matthew Shank, president emeritus of Marymount University, asked the students if they had had the opportunity to participate in interprofessional education. All three students replied that they had not had much opportunity to learn with or work with people from other professions but that they saw the value in doing so. Walker said that his program has been largely theory and classroom based, so learning with students who participate in more real-life experiences (e.g., working in a clinic) would bring a much needed balance to the program. Hamlin said that a unique aspect of her accelerated nursing program is that everyone comes with degrees from different disciplines and has had different experiences. This allows people with different perspectives to share and learn from one another. However, she said, it would also be beneficial to have collaborative experiences with people who will be working in the health field with nurses. Shank added that another option for interprofessional education would be to have instructors from different disciplines working together with traditional health professions faculty. For example, an academic could team up with a practitioner to run a community-based project, giving students the opportunity to learn different aspects of the work from different people.

Mentoring

A workshop participant asked the students if they had formed any relationships with mentors during their education and, if so, what role the mentor has played in their success. Vencel replied that her professors from the cultural psychology and global mental health courses have both stood out as mentors more than other professors, due in part to the more intensive and involved nature of classes that engage the community. Hamlin agreed and said that her relationship with her clinical instructors has been extremely

important in giving her hands-on experience and fostering confidence in her ability as a nurse. Walker said that the new program director at his school has been leading an effort to do more community outreach and that he is excited about the opportunity to get involved in shifting the culture toward this goal.

FACULTY PERSPECTIVE

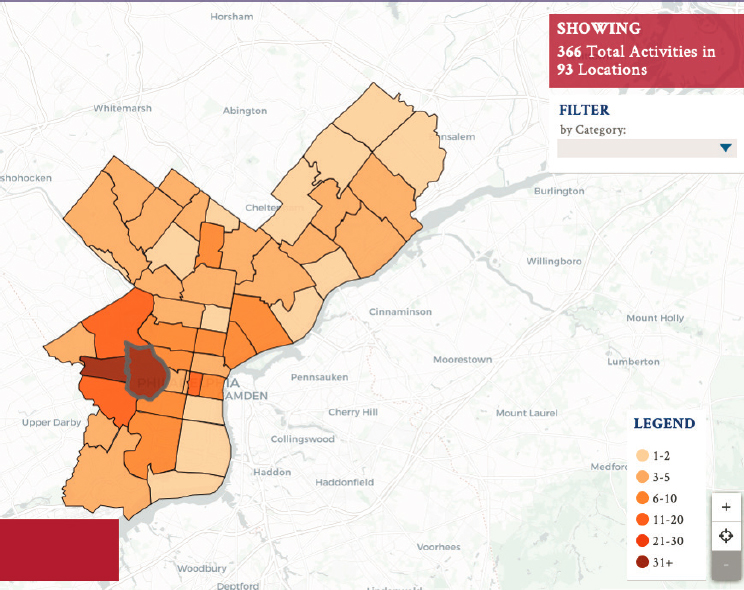

The reputation of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia has not always been positive, said Terri Lipman, assistant dean for community engagement at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. When Lipman first arrived at Penn, she recalled, she attended a meeting where a community member said, “Penn and Children’s Hospital comes into the community, you collect your data, you do your projects, and you leave us with nothing.” This message, Lipman said, resonated with her and has guided her community-based work. Lipman displayed a map (University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, 2019) of Philadelphia that showed the number of community engagement projects across the city (see Figure 4-1). This map, Lipman said, shows not just what they have done, but how far they have to go.

In addition to Lipman’s work as dean, she is also a nurse practitioner at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia working with children with endocrine disorders and diabetes. In her role as a clinician, she said, she has “firsthand knowledge of what happens when we don’t address social determinants of health.” Children with diabetes from well-resourced families have great outcomes, whereas traditional disease- and hospital-focused interventions have “not moved the needle with underresourced families.” A new approach, Lipman said, is sending community health workers into patients’ homes; these workers address only the SDH and do not discuss diabetes management at all. Preliminary data suggest that this approach is improving diabetes outcomes, she said. Lipman said that health professionals often think that the answer to poor health outcomes is more education and more intervention from health professionals themselves. However, she said, “professional teams don’t necessarily address the issues we need to address,” whereas community health workers may be able to move the needle when clinicians cannot. Lipman was also clear that any community-engaged program she is involved with that addresses the SDH also includes mental health. In the community setting, she said, the two cannot be separated.

Exploring Best Practices for Community-Based Programs

Lipman shared the lessons she learned from facilitating and leading community-based programs. First, she said, these types of experiences require flexibility on the part of students, faculty, and institutions. Nursing

SOURCES: Presented by Terri Lipman on November 14, 2019; map licensed by OpenStreetMap, © OpenStreetMap contributors; data available under the Open Database License.

students are accustomed to working in a hospital, where things are quite regimented and scheduled. In contrast, community-based work is less predictable; for example, a high school where a nursing student is supposed to report may be on lockdown due to violence. Faculty and educational institutions must be flexible as well, Lipman said. Community-engaged research and teaching can take an enormous amount of time and effort, particularly when compared with traditional methods, such as giving a PowerPoint lecture. Institutions need to be flexible when making promotion and tenure decisions; community-involved faculty may spend their time and energy on activities that are not traditionally valued but that are key to building strong relationships with the community.

Second, programs need to be community-driven and based on community goals. As an example, Lipman discussed a program she runs called Dance for Health. This program was born out of a community discussion

about the community members’ desire to have an active, indoor, inter-generational activity that is fun for everyone. The academic and practice partners have a goal of improving health and take health measurements to track progress. The community partners, on the other hand, have said that “what really brings them there is the social support and the relationship building.” Still, Lipman said, the community members are excited to track health measurements because they love the idea of improving their health through dancing. The program is co-owned by the community, Lipman said, which means that it continues during academic breaks and is independent of student or faculty turnover. The program also involves local high school students, who help obtain the health data and then present the data around the country, along with the nursing students. The “heart of the program” is outside of the academic institution, Lipman said, so it is sustainable and community-driven.

The third lesson that Lipman offered is that these programs are relevant for all health professionals, no matter where they end up practicing. Lipman said that she sometimes gets pushback from nursing students who are planning to work in non-community settings, such as intensive care units. These students do not see the relevance of community work to their education. However, Lipman said, the relationship-building skills that students learn in the community are fundamental to providing good health care and to being able to work successfully with patients and families. For this reason, Lipman said, she believes that all students should be exposed to community engagement work, not just those who express an interest in it.

Finally, Lipman said, community-based experiences work best when students and faculty are committed for a long period of time. Rather than doing projects one semester at a time or on a drop-in basis, Lipman’s goal is for students to stay with one community experience throughout their education. Lipman said that when entire groups of students come and go, it takes time to rebuild relationships. If students need to leave a project for some reason, there should be a handoff process in order to ensure continuity. Lipman added that faculty also need to be committed; they need to have “the passion and the interest” to engage with the community and to build relationships. If faculty are not fully committed to working with the community, she said, the relationships and projects will not be mutually beneficial or sustainable.

DISCUSSION

Given the enormous benefits and power of experiential learning and community-based work, Talib asked, why are these types of educational opportunities not more readily available? Shank replied that a lot depends on the vision of the university: “If you don’t have passion at the top for

this, it’s not going to work.” Even if faculty and students want to do community-based work and are passionate and committed, there are limits to what can be done without buy-in from the university. People at the top of the university or organization, Shank said, need to be consistently talking about community engagement and incentivizing people to carry it out. Incentives could include making community engagement part of tenure decisions or offering community engagement grants. Lane agreed but said that even when leaders are committed to community engagement work, they sometimes do not understand what it takes to actually conduct it. For example, the refugee health class she runs at Syracuse University and at Upstate Medical University involves a great deal of work, including finding families willing to participate, securing funding for stipends for the families, and ensuring that students can get to and from their frequent home visits during the semester. A colleague of Lane’s mused about scaling up the program but did not take into account the massive time commitment required for faculty. Newton added that even seemingly straightforward logistical issues—such as housing and bus routes—can derail an experiential learning opportunity if not dealt with ahead of time.

Another reason that experiential opportunities sometimes fail is a lack of intentional and careful planning and management of the project, Newton said. For example, if a student shows up to an organization that is not prepared for that individual, it is a negative experience for both the student and the community, and it can alienate the student from participating in the future. This is a particular hazard when sending students into emerging or worsening crises, such as a community after a hurricane, Newton said. These situations can present opportunities for communities to receive much needed help while at the same time allowing students to gain hands-on experience, but the projects need to be carefully planned and managed so that both sides have a constructive and mutually beneficial experience. An experiential learning project, Newton said, is “not worth doing unless it’s done well.” Shank added that the expectations of both the community and the students need to be managed, so that both sides understand their roles, responsibilities, and goals. Lipman concurred and noted that students’ expectations and intentions are sometimes not aligned with those of the projects; for example, students may want to participate because it will look good on their résumé. Faculty should carefully consider the students who are being sent into experiential learning projects in order to ensure a good match. Lane told a story about this type of issue, in which a student failed to follow through on a research project that the community partner had worked hard on. These types of failures can “burn bridges” in communities, Lane said, and emphasize the need for careful management.

REFERENCE

University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. 2019. Community engagement map. University of Pennsylvania. http://whimsymaps.com/view/sonfacultycommunity_2019 (accessed January 22, 2020).