The workshop’s first session, moderated by Tina Hesman Saey, a senior writer and molecular biology reporter for Science News, explored how consumers are engaging—or are not engaging—with direct-to-consumer (DTC) and consumer-driven genomics services and whether there are lessons to learn about overall health engagement. This session also provided insights into how patients and providers are using genomic data obtained through consumer genomics applications along with information from other sources to make health care–related decisions. Cinnamon Bloss, an associate professor in the psychiatry and family medicine and public health departments at the University of California, San Diego, spoke about the history and future of consumer genomics use. Then Sara Altschule, a freelance writer for Bustle magazine, and Dorothy Pomerantz, a managing editor at FitchInk, described their personal experiences after receiving results from DTC genomic testing.

EXAMINING THE HISTORY AND FUTURE OF CONSUMER GENOMICS USE

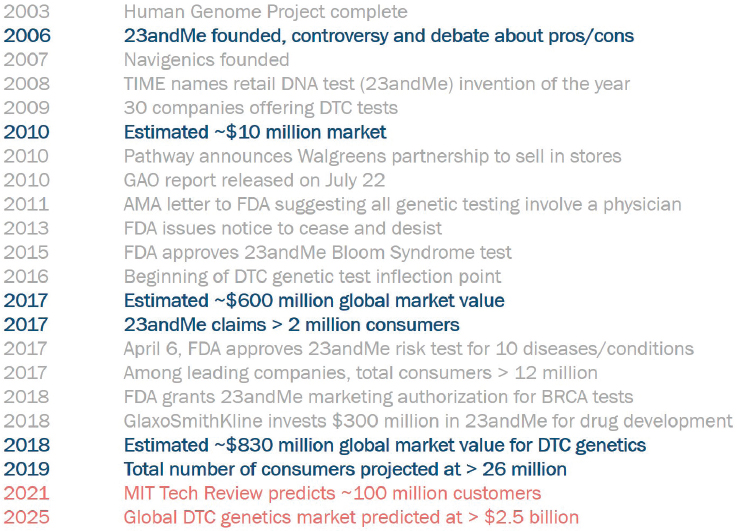

The story of DTC genomics has captivated both scientists and the public since its appearance shortly after the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, Bloss said. She mentioned some of the challenges that the field has experienced since its inception, particularly regarding regulatory permissions to offer health-related testing (see Figure 2-1). In terms of consumer use, she said, the decreasing cost of DTC testing as well as the increasing market value for DTC companies led to an increased number of consumers purchasing DTC genomic tests. It has been estimated that the market value for DTC genomic testing in 2010 was $10 million (Wright

SOURCE: Cinnamon Bloss workshop presentation, October 29, 2019.

and Gregory-Jones, 2010) but that by 2018 the estimated market value had risen to $830 million (Ugalmugale, 2019).

To get an idea of the impact that DTC genomic testing has had on consumers, Bloss and her colleagues recently conducted a rapid review of the literature, finding 69 articles focusing on genetic health risk tests. One challenge in understanding consumer motivations is that about half of the published studies to date have been based on cohorts of consumers from only three studies: the Impacts of Personal Genomics (PGen) study (Krieger et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2017), the Scripps Genomic Health Initiative (Bloss et al., 2010; Darst et al., 2014), and the National Institutes of Health Multiplex Initiative (Kaphingst et al., 2012). Because the participants in these studies were recruited a decade ago, they are likely to be early adopters on the standard bell-shaped curve of consumer-driven technology adoption, Bloss noted. The diffusion of innovations theory argues that adopters in each of the various categories—innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards—have different characteristics (e.g., late adopters tend to be more conservative) (Rogers, 1962). Because consumer genomics has moved from the early adopter phase to the

early majority phase, existing studies may not accurately inform use by and impacts on the current consumers, Bloss said.

The literature review indicated that the participants in the cohort studies to date have been mostly white and of high socioeconomic status, Bloss said, and their primary motivations for testing have been learning about ancestry, health, and family health history or simply curiosity. Few studies, she said, have examined differences in motivations and outcomes as a function of demographic diversity, though one study did find that there were few differences in motivations as a function of race (Landry et al., 2017). Bloss noted, however, that the groups in that study were very small. Changes in health behavior (e.g., exercise, diet, smoking) were self-reported by about 25 percent of the participants, though studies using objective and validated measures of behavior find few or no changes (Gray et al., 2017). In the few studies where changes have been observed, she said it was difficult to determine the size of the effects and their duration. Another area where more research may be needed is in understanding whether there are behavior changes in individuals who receive positive BRCA results from DTC genomic tests because those tests were not on the market 10 years ago, Bloss said.

Critics of DTC genomic testing have raised concerns that consumers may experience adverse psychological reactions, such as anxiety and depression, after obtaining the results of their tests. Currently, Bloss said, there is little evidence that this concern is valid, though she added that for the small number of individuals who do experience adverse responses, the consequences may be significant (Oliveri et al., 2018). For that reason, she said, it is important to have resources available to help those individuals who do experience significant psychological distress after receiving their test results.

Researchers have also found that about one-third of consumers share their DTC genomic test results with at least one health care provider, usually the individual’s primary care physician. Data on the characteristics of individuals sharing DTC data with their primary care physician are also inconsistent, Bloss said. The outcomes of sharing vary, but in general the result is that individuals are reassured by their providers more often than providers end up changing the way they manage their patients’ health. Consumers, Bloss said, believe they have a right to access genomic information without involving their physicians but also that physicians should be available and able to provide counseling even though they did not order the tests. This can place a considerable strain on physicians, Bloss added, given estimates suggesting that there have been some 3.6 million instances of DTC data sharing with physicians in the United States while there are only 850,000 practicing physicians in the country.

Going forward, Bloss said, she expects consumer uptake to continue rising exponentially because companies are now engaging in aggressive

and targeted marketing campaigns. One key implication is that advertising, combined with the low cost of obtaining DTC genomic testing, will drive purchasing until the market is saturated, whenever that might be. Because data on consumer trends are limited, she added, newer studies—for example, using social media strategies to identify trends in real time—may be needed to assess the influence of demographic factors and the effects of emerging issues.

The rise of DTC genomic testing is taking place against the backdrop of a broad and shifting consumer health landscape that expects patients to be more autonomous and that offers more DTC health products, such as heart rate monitors and hearing aids. In addition, there are evolving ideas about what it means to be an expert and about the extent to which people need expert knowledge. The implication here, Bloss said, is that consumers will increasingly seek after-the-fact physician guidance regarding genomic and other DTC health tests.

The upward trajectory of people being tested outside versus inside the medical model is part of a broader trend of consumer interest in DTC products and devices that is likely to continue, Bloss said. “I think it would be useful to learn about this phenomenon, how it occurs in the trenches between physicians and their patients. Develop and teach ways for physicians and patients to approach these interactions . . . and think of this as an opportunity to engage people.”

CONSUMER PERSPECTIVES

“In everyone’s life, there are numbers we always remember, such as your Social Security number, your address, and your phone number,” Sara Altschule said, “and now, thanks to my 23andMe genetic health report, I now have another number I will never forget: 617DELT.” That is the mutation in Altschule’s BRCA2 gene that increases her risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer during her lifetime. While estimates vary, studies suggest that between 27 and 84 percent of women with a BRCA2 variant will develop breast cancer and 11 to 30 percent will develop ovarian cancer by age 70 (Kuchenbaecker et al., 2017). About 12.8 percent of women in the general population will develop breast cancer, and 1.3 percent will develop ovarian cancer in their lifetimes (Howlader et al., 2019).

Getting that news at age 30 was quite devastating, Altschule said, particularly because she was never expecting to receive this news in the first place. Her sister had given her a 23andMe kit as a holiday present, and the two siblings were excited to learn more about their ancestry. It was no surprise to her that her results showed she was 77.1 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. While viewing the report, she saw the option to add genetic health results for an additional fee, and curiosity prompted her to add that package to

her report. Upon viewing the updated report, she was relieved to find that the only red flag was the possibility of being slightly sensitive to gluten. Six months later, she received an email from 23andMe informing her that the company had received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for DTC genomic tests for cancer risk, which included testing for three BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants associated with an increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer in women and prostate cancer in men that are most common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish decent.

This was a startling revelation, Altschule said, because no one, not even her doctor, had ever told her about her increased risk. She called her mother and learned that there was no history of breast or ovarian cancer in her mom’s family, although her father’s cousin had battled breast cancer and died from ovarian cancer and also had a BRCA2 mutation.

At 2:00 on a Sunday morning, Altschule logged into the 23andMe website to see the new results. “When I saw the words, ‘one variant detected,’ my heart sank,” she recalled. In that moment, she felt anxiety, fear, and shock, and she spent the next several hours searching for every piece of information she could find, from Wikipedia pages to Facebook groups. By that Friday, after learning all that she could about what it meant to be BRCA2 positive, she sat in the office of a genetic counselor hoping to hear that it was a false positive. That was not the message, however, and a subsequent blood test confirmed the 23andMe result.

Altschule said that after a week of scouring the Internet, having the genetic counselor’s reassurance and perspective was important. “Knowing that my risk of developing breast cancer at age 30 was 10 percent, versus the very scary lifetime risk of 85 percent, was a much easier pill for me to swallow,” Altschule said. Moreover, she learned that her risk of developing ovarian cancer was significantly decreased because she had been taking oral contraceptives and, furthermore, that she would not face the choice of whether to have preventive surgery to remove her ovaries until she was around age 45.

The options going forward were still not great, she recalled. One was to have a mammogram, breast magnetic resonance imaging, pelvic ultrasound and exam, and CA-125 blood test every 6 months. The other option was to have a preventive double mastectomy with reconstruction at that time and consider having her ovaries removed at age 45. “I always tell people having a double mastectomy was the easiest and toughest decision of my life,” she said. Though she was worried about how the decision would affect her physical and mental well-being, after spending time researching and talking with her family and friends and other women who carry the same gene variant, she knew what she wanted to do. “I can easily say today I have zero regrets, and it was the best decision for me,” Altschule said.

When asked if she would recommend genetic testing to others, Altschule tells others to make sure they really want to know the answer. “It is like opening Pandora’s box,” she said. “You cannot unsee the diagnosis and you cannot unknow the information,” and the information can affect family members as well. In her mind, she said, her 23andMe results not only saved her life, but may save the lives of people in her family who now know they are also BRCA2 positive. As the end of the day, Altschule said, she feels lucky. “I am a true believer that knowledge is power, and I have never felt more powerful.”

Dorothy Pomerantz’s story was similar to Altschule’s in that she is Ashkenazi Jewish, too, with an aunt on her father’s side who died of breast cancer. At one point in the past, she said, she had talked to her doctors about genetic testing, but none thought that her family history was significant enough to indicate the need for testing. When she decided to send a sample to 23andMe, she was expecting confirmation that she did not carry BRCA mutations, but the moment she looked at her results after quickly moving through the long tutorial included with them, her world stopped: she had a BRCA1 mutation. This meant that her risk of developing breast cancer or ovarian cancer by age 70 was 40–87 percent and 16–68 percent, respectively (Kuchenbaecker et al., 2017). “In that moment my life changed,” she said. “I stood there in my home office and I was stunned.”

Her primary care physician connected her to a breast cancer specialist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital who saw her the following day and reiterated the need for confirmation testing before moving forward. A second test confirmed the 23andMe result, and after a long and reassuring conversation with her genetic counselor, she decided to have a preventive double mastectomy and have her ovaries removed. With two children and a supportive group of friends who were going through menopause, Pomerantz said it was an easy decision for her to make. The ability to be there for her children growing up and having years of relief was worth the short-term pain, she added.

Nearly 1 year later, Pomerantz said, she is healthy and grateful that she learned her BRCA status when she did. “I got information that I was able to act on, and while the surgeries were difficult, they were nothing like what those surgeries would have been if I had cancer,” she said. At the same time, she was left with some ambiguous feelings about how she received the information. Working full time with two children, Pomerantz said, she would have been unlikely to seek genetic testing or take the time to see a genetic counselor because she was unware of her increased risk; on the other hand, getting the results via an email was a terrible experience. “In that moment,” she said, “I felt confused and alone, and my mind immediately went to the worst places.”

Pomerantz said she was lucky to get her doctor on the phone quickly before she “went too deep down the BRCA Google hole,” as she put it, but she worries about the women who cannot get their doctors on the phone or who do not have doctors at all. Because about half of the women with a BRCA mutation have no family history of breast cancer, there may be many women who turn to 23andMe for other reasons and get surprising news with real consequences, as Pomerantz and Altschule did.

Moreover, 23andMe looks at three BRCA variants that are prevalent in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, only some of a much larger number of BRCA variants linked to breast and ovarian cancer, which means that many women stand to receive a “clean bill of health” that could be misleading. “This is not to say that 23andMe should not offer a health screen,” Pomerantz said, “but when dealing with serious health issues, people need someone to walk them through it.” She said that she wishes she had received her diagnosis from a person rather than from an email so that she could have had support in that moment.

The customer experience matters, and home genetic tests could be more valuable if they came with the opportunity to talk to a genetic counselor, Pomerantz said. Before deciding to have testing done by 23andMe, she said, she felt that she knew a lot about genetics, but being informed about genetics is not the same thing as being ready to handle the emotional impact of a diagnosis. “The information in these results are complicated and nuanced,” she said, “and, as with every big health decision in our lives, we need people to help walk us through the dark.”

DISCUSSION

Communicating Information with Family Members

Sharing information with family members can be challenging, one workshop participant said, asking Altschule and Pomerantz how they went about sharing their BRCA status with family members. Talking to her mother immediately was easy, Altschule said, but it was difficult to talk to her sister, who would have a 50:50 chance of also having the same BRCA2 variant. She relied on her genetic counselor and her mother to help her come up with the right words to use. Working with a genetic counselor was also crucial for her in helping her understand the impact for her family, she added, as the counselor walked her through how that conversation with family members might go and the best approach for communicating information. Because the mutation was present on her father’s side, she had to tell his brother about the results as well. Written information, she said, was helpful to have when talking with relatives. Altschule said that when her uncle took the information to his family practitioner, he was told he did

not need to be tested because he was a man, despite the fact that he had three daughters and a son. “I just found it so upsetting that this was what his doctor told him,” she said. It is an incorrect conclusion that men cannot transmit breast and ovarian cancer mutations, a participant added, and this is an area where many physicians do not properly counsel their patients.

Pomerantz told both of her parents and her brother about her results immediately, but she said there was no sense of alarm. She also told her cousins who have daughters, but no one in her family has opted to get tested despite the fact that she gave them vouchers for genetic testing at a reduced price that she had received from her genetic counselor. While Pomerantz herself does not necessarily understand that decision, she said that wanting to know has to be an individual choice. Age is important as well, Altschule added, saying that she was ready to hear that type of information at 30, but she may not have been at 21.

Asked whether there is literature on why people choose not to get testing, Bloss said that that some people feel they do not want to know and go through their lives worrying about possible consequences. She also cautioned that, given the trends in the types of consumers who have undergone testing, there could be a self-selection bias in terms of the literature on this to date.

Patient Resources and Support for Understanding Risk

One workshop participant asked whether it is difficult to find information about BRCA mutations online, and both Pomerantz and Altschule said that finding information was not the problem. Altschule cautioned that it is easy to go down the “rabbit hole,” given the breadth of resources available online, when you do not have a person delivering the results and are viewing them for the first time at 2:00 a.m., but she added that one thing she noticed was missing from the online conversations were the experiences of women and men who had a gene mutation but did not yet have cancer. Pomerantz said that what was missing for her were the experiences of individuals receiving surprising information from at-home genetic tests.

Getting that information is going to be hard no matter how it is received, but having a knowledgeable person on the phone to walk through what the information means would be ideal, Altschule and Pomerantz agreed. Another challenge is that the knowledge base about genetics and risk is still early, Pomerantz added, and having a genetic counselor there to help is important. The DTC tests also have limitations, and that is an important part of what needs to be discussed, she added. Having information that is personalized would be helpful, Altschule said. She said she would have preferred to see the risk information based on her current age rather than staring at the 85 percent risk that showed up on her results page.

In terms of understanding risk, there may be a psychosocial piece that is missing, a workshop participant said. While DTC tests have to achieve a certain level of comprehension among consumers to be considered safe and effective, the idea of what the information may mean emotionally for the consumer at that time may also be important.

Data Privacy and Research

One workshop participant asked whether Pomerantz and Altschule were concerned about how their data would be secured and used. Initially, Pomerantz said, she was very concerned about the safety of her data and chose all of the privacy options 23andMe offered when signing up for the test. However, after she received the test results, she changed all those options because she felt she wanted to do everything she could to help others. “If doctors are going to be able to take my DNA and use it for research, then I want to make that as available to them as possible,” she said. She also joined the All of Us Research Program1 with the same idea in mind. Altschule said she did not put much thought into her decision to make all of her data available for research when she took her test, but now believes it was the right thing to do. Asked if they thought differently about researchers having access to their data versus a pharmaceutical company, both indicated that they did not view the uses differently and hoped that pharmaceutical research could ultimately help patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations as well. Both said their primary concern was that insurance companies might someday deny coverage because of their mutation status.

There may also be opportunities for using the data from the millions of consumers of DTC genomic tests. If those consumers agreed to share their data, Geoffrey Ginsburg said, you could create a virtual cohort that would be many times the size of the All of Us Research Program at a fraction of the cost. “I think something worth thinking about are the latent assets that the consumer industry has created that could actually catapult the science and research further than anyone has gone before,” he added.

___________________

1 For more information about the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us Research Program, see https://allofus.nih.gov (accessed December 16, 2019).