4

Overcoming Barriers in the Field to Bolster Access and Practical Use of Innovations

The second session of the workshop focused on overcoming barriers in the field to bolster access and practical use of innovations. The session’s objective was to elucidate the key barriers and facilitators to implementing innovative approaches that empower end users and patients, facilitate positive behavior change, and ultimately reduce the health impact of infectious diseases at the community level. The session was moderated by Eva Harris, director, Center for Global Public Health, University of California, Berkeley. Collince Osewe, founder and chief executive officer, ChanjoPlus, described how ChanjoPlus empowers health workers to improve immunization service delivery through digital innovation. Brian Bird, research virologist, One Health Institute, University of California, Davis, discussed the translation of data and modeling insights into improved capacity for detection and response using examples from his work following the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa. Carolina dos S. Ribeiro, senior policy advisor, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, the Netherlands, discussed issues related to global data sharing and collaboration and suggested a set of practical tools to enhance the timely sharing of outbreak data. Fadi Makki, founder, Nudge Lebanon and the Consumer Citizen Lab, described the application of insights from behavioral sciences to enhance acceptability and adoption of innovations across diverse social and cultural contexts.

DIGITAL INNOVATION TO IMPROVE IMMUNIZATION SERVICE DELIVERY

Collince Osewe presented on how health workers can be empowered to improve immunization service delivery through digital innovation. He described how he drew on his experience as a community health volunteer in Kenya to develop the ChanjoPlus mobile app to support the equitable delivery of vaccines at the community level. In Kenya and other countries in Africa, immunization management and reporting are still manual, paper-based processes. Community health workers visit households to identify underimmunized children and refer them to health facilities. This process typically depends on immunization booklets, which contain a child’s vaccination history and must be updated every time a mother brings the child to a health facility. These booklets serve as the source documents for the entire immunization reporting structure. He explained that this manual process does not provide real-time visibility of performance and contributes to poor disease surveillance and inconsistencies in reporting.

He noted that Africa faces a substantial burden of underimmunization of children: an estimated 19 million children across the continent are underimmunized, and nearly one-fifth of children have not had all basic vaccinations (WHO, 2019f). He added that these factors contribute to a disease burden of $5 billion (Ozawa et al., 2017).

Empowering Health Workers and Improving Service Delivery with the Platform

Osewe described some of the challenges facing health workers in countries in Africa. The new generation of health workers frequently relocates, because there are multiple facilities offering the same spectrum of services. They conduct their work in the context of poor data, limited visibility, and ineffective vaccination tracking tools. Medical facilities are often fragmented and do not share their data with one another. To help address some of these challenges, ChanjoPlus was developed as a decentralized mobile health platform that allows health workers to access a centralized database of immunization status information. The platform does not require a smartphone or Internet and helps health workers to accurately identify children and their immunization records. With this information, they can track children who miss vaccines, and improve immunization data for real-time monitoring.

Community health volunteers register children by dialing the code into a mobile phone and using the platform to capture the child’s demographic information and update the child’s immunization status. Each child is assigned to the identification number of an adult within the household. During routine immunization services, a community volunteer can vali-

date the adult’s identity and then view the vaccines that each child in the household has received, as well as any vaccines that have been missed. The community health care worker has credentials to determine which vaccines to administer and then uses the platform to update a child’s vaccine status. Once immunization updates are captured, they are available on the real-time immunization performance monitoring dashboard, which is accessible to the Ministry of Health.

Osewe described the benefits of this type of simple technological innovation. ChanjoPlus has been able to increase accountability for immunization resources and help to prevent waste and shortages, because real-time data can be used to determine the demand level in each facility and region. The platform also offers population-wide analytics on immunization and vaccinations in real time. In addition to improving data quality and verifiability, it can improve the efficiency of health workers because it provides immediate access to a child’s immunization status, reducing service delivery times from 30 minutes to less than 5 minutes. He added that ChanjoPlus has also been found to reduce the cost of vaccination by approximately 47 percent, from $7.00 per child to $2.50 per child. ChanjoPlus is suitable for scale up across low-resource settings in sub-Saharan Africa, said Osewe. The platform has already been successfully piloted with about 14,000 children, and scale up is planned to 100,000 children in western Kenya during 2020.

Adoption and Sustainability of the Platform

Osewe described the challenges that ChanjoPlus has encountered while piloting the program in Kenya. Many organizations are working on innovation, but there is not a controlled environment for determining which innovations should be scaled up. ChanjoPlus is competing with large international companies that are entering the space with competing apps and innovations, rather than working with local stakeholders to develop in-country solutions. ChanjoPlus’s path to adoption and sustainability relies on partnerships with implementers as well as partners who inform policy and uptake, he noted. ChanjoPlus has an incentivized cadre of volunteers that benefits from the currently devolved function of health care in Kenya: community health volunteers are recognized as part of the health care workforce and paid by the Kenyan government. He remarked that ChanjoPlus adds value across the value chain, from efficiency in service delivery to tracking children who need vaccinations to data analytics. He attributed the adoption of the platform to his company’s human-centered design approach that engaged with mothers and health care workers, who voiced their challenges and offered solutions in the design of the platform. To ensure sustainability, they are seeking government uptake by framing the platform as a cost-reduction strategy delivered through a subscription model.

USING DATA AND MODELING TO IMPROVE DETECTION AND RESPONSE

Brian Bird explored how data and modeling insights can be translated into improved capacity for detection and response by reflecting on lessons learned during the West Africa Ebola outbreak and the work of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID’s) PREDICT project. He focused on community engagement, describing the local community as the grassroots stakeholder that can serve as the greatest facilitator as well as a potential barrier to successful implementation of a One Health approach to disease surveillance and supporting public health on a global scale. One Health zoonotic disease surveillance methods are critical for early outbreak detection and response, he maintained.

Lessons from the West Africa Ebola Virus Outbreak

Although he had worked on other filovirus outbreaks, the West Africa Ebola outbreak was an eye-opening experience for Bird. From 2013 to 2016, waves of human-to-human transmission led to more than 28,000 cases of Ebola and 11,000 deaths in West Africa. Past outbreaks had been smaller and less complex, with community relations built around a single village or country. However, when an outbreak expands into multiple countries and linguistic environments, community relations can quickly spiral out of control and it is impossible to respond effectively if communities do not trust emergency response teams.

Bird emphasized that the public health, One Health, and global health cadres are failing to scientifically communicate their messages in clear, concise ways that people can understand. He noted that poor community trust and engagement coupled with a lack of understanding of communities’ fundamental motivations and beliefs stymied detection and control efforts during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. For example, the personal protective equipment worn by researchers during an outbreak response can be frightening and intimidating to communities. Furthermore, the concepts of disease causation do not necessarily exist for people in Sierra Leone, who tend to have a more holistic construct of the world that does not encompass things such as microbes that cannot be seen, making it challenging to explain viral diseases to people in order to prevent transmission. To address this challenge, they used hand-drawn picture-books created by local artists as information-conveying tools in Sierra Leone to explain how to prevent Ebola transmission.

Adding further complexity, proper preparations of corpses for burial are required to control Ebola, but in West Africa, burial practices are intense community efforts that can lead to infectious corpses becoming powerful vectors of transmission. In one instance, 75 cases of Ebola were attributed

to a single infectious corpse. The active inclusion of traditional healers and leaders in response efforts helped to change practices to allow for medically “safe and dignified burials” to break transmission chains. Unfortunately, community-level resistance and mistrust remained. He added that without careful attention, these types of issues will impede the deployment of any innovative, enhanced detection or response efforts.

PREDICT Surveillance Program and the PREDICT Ebola Host Project

Bird explained that the PREDICT project, funded by USAID, emerged from efforts during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The project was developed to perform global surveillance for emerging viral pathogens at the key interfaces between wildlife reservoirs, domestic animals, and people. It aimed to conduct One Health surveillance in real time while looking for novel emerging pandemic threats across a spectrum of transmission: virus evolution, cross-species transmission, animal-to-human spillover, human-to-human transmission, and international spread. PREDICT was a global project, operating in more than 30 countries in Africa and Asia between 2016 and 2019, that strengthened training and capacity building in these regions.1

Within the broader PREDICT program, Bird explained that the PREDICT Ebola Host Project (EHP) was launched with three core objectives: (1) to identify the animal origins of the Ebola virus; (2) to increase capacity for One Heath disease surveillance, including field sampling, laboratory, and behavior assessment; and (3) to work hand in hand with local communities, traditional leaders, and governments.

PREDICT EHP was established in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—the three countries most severely affected by the West Africa Ebola outbreak—to conduct an in-depth, high-volume, high-intensity animal sampling to find the elusive reservoir of the Zaire Ebola virus, which was the causative agent of the West Africa outbreak as well as the more recent cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Outcomes of the PREDICT Project

Bird said that the project did not find the reservoir of the virus, although a bat infected with what looks like Ebola Zaire was found in Liberia. However, PREDICT EHP did achieve other substantial gains. Working hand in hand with traditional leaders and government structures, they were able to bring scientific information and capacity training down to as close to the village level as possible. The EHP teams included government representatives, vet-

___________________

1 More information on the PREDICT project can be found at https://ohi.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/programs-projects/predict-project/about (accessed March 3, 2020).

erinary and medical surveillance officers, and laboratory technicians. They were able to sample a wide variety of environments, ecosystems, and species across the three countries in one of the largest in-depth biodiversity surveys ever done in West Africa. Bird noted that PREDICT EHP sampled 19,800 animals—primarily bats, because they had been less studied in the region. They trained 250 people in various One Health skills, including laboratory and surveillance skills, and worked in 60 communities across the region.

He said that each of these communities was provided risk-avoidance information and materials, and the EHP team worked with these communities to deeply engage them and help them understand the work being done. To do so, each team explained to the community members that they were searching for the source of the virus that may have killed loved ones within that community. Although PREDICT EHP did not find Ebola Zaire, the teams’ work at the reservoir taxa level enabled them to find an entirely new species of Ebola virus, the Bombali virus, which raised the species count from five to six (Forbes et al., 2019; Goldstein et al., 2018). This was the first discovery of an Ebola virus that had not yet caused a known human or animal death. The co-discovery of Marburg virus in bats occurred almost simultaneously, he added (CDC, 2018). Marburg virus is a known killer of humans in central, eastern, and southern Africa, so the discovery of the virus 3,000 kilometers due west had significant public health implications (CDC, 2018).

PREDICT Project Successes and Lessons Learned

Bird outlined some of the lessons learned from the PREDICT project, as well as factors that made the project successful. The project used an innovative, integrated approach to finding viruses that highlights the “unknowns” about what to do next to manage risks (e.g., it is not yet known whether the Bombali virus is a human pathogen because it was found in a reservoir species). It is important to explain these types of discoveries in an appropriate way to policy makers and others, he noted. For instance, PREDICT EHP personnel worked hand in hand with the government of Sierra Leone to shape consistent and noninflammatory public messaging after the new viruses were discovered; extensive local public engagement reduced fear and misinformation.

The EHP team developed trust as they continuously collected samples in communities for several years and returned to communities to report the discovery of the two viruses, including one that is a high-risk public health pathogen and the other that is of unknown pathogenicity. Having built high trust with the community allowed for open and honest discussion about risks, he said. For example, the Bombali virus was found in a bat that often lives in the houses of community members—it is difficult to explain that Ebola has been found in a bat in a person’s house, but that the risk is not yet known. Scientific work is needed to develop strategies to convey those types of messages, he said.

The PREDICT project demonstrates that overcoming trust barriers is necessary to save lives and that integrated One Health approaches paired with in-country governments do work, said Bird. Researchers should maintain a consistent presence in communities, working in partnership with community members, and convey scientific information in a way that people understand and accept. “The best next-generation diagnostic tools will not be of any benefit if people are reluctant to come to the clinic,” he said, emphasizing that the ability of communities to augment response efforts should not be underestimated.

OUTBREAK-RELATED DATA SHARING AND COLLABORATION: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Carolina dos S. Ribeiro examined issues related to the global practices of sharing microbial and genetic data during outbreaks. She also explored strategies for fostering collaboration and enhancing timely data sharing to tackle microbial threats.

Lessons from Recent Epidemic Responses

Ribeiro explained that recent global health crises caused by emerging infectious diseases, from Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) through Ebola to Zika, have revealed fundamental challenges in collaboration and data sharing that have affected epidemic investigation, national and international response, and the affected communities. For instance, the 2012 MERS epidemic in the Middle East highlighted issues of data ownership. The Saudi government strongly opposed a foreign patent on the virus sequence used to develop diagnostic tests on the grounds of protecting their sovereignty and national interests, thus restricting the sharing of virus materials and data from the outset of the epidemic. She noted that as a zoonotic disease with camels as a source of infection, MERS required a strong integrated response at the human–animal interface under the One Health approach. Instead, there was strong denial of animal involvement from the camel livestock sector and late engagement of animal health authorities (Keegan, 2014).

During the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, there were gaps in data sharing even when the number of cases was peaking (Yozwiak et al., 2015). No new virus sequences were released between August 2 and November 9 of that year, which was the period in which the largest number of new cases were discovered (Yozwiak et al., 2015). Genome sequences were shared only sporadically, even though more were known to have been generated. She added that research, response, and data sharing were uncoordinated and misaligned with the public health and decision-making needs of the national governments. She described the 2015 Zika epidemic as a clear example of government and regulatory restrictions on the international sharing of

pathogen materials and data (Cheng et al., 2016; Koopmans et al., 2019). An external consortium initiative worked to develop external quality assurance and validation for Zika diagnostics, but after 1 year, only three laboratories had managed to complete all of the steps. Although this delay was primarily attributable to the lack of capacity and shipping materials, noted Ribeiro, the need to obtain government permission was also time consuming.

Data-sharing issues extend beyond outbreak timelines, said Ribeiro. In February 2019, for example, The Telegraph newspaper reported that samples from Ebola patients in West Africa had been exported without their consent and were being held in secret in laboratories across the world. The article reported that a laboratory was advertising virus samples online for a price quoted as being 170 times the price of gold (Freudenthal, 2019). Scientists and Ebola survivors in Africa accused the laboratories of biological asset stripping and requested their samples back for research. When questioned, the laboratory responded that they had shared the samples freely with other laboratories around the world and were also providing services such as sample extraction, purification, and characterization. Under European Union law at the time, the laboratory claimed to have intellectual property rights to offer it on the market at cost price. Ribeiro remarked that during outbreaks, researchers—particularly those in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)—are often so busy supporting the response that they do not have the time or resources to engage in research. She added that most of those countries do not have facilities to store samples for future use; thus, they lose long-term access and control over samples.

Data Sharing in a Time of Transition

Data sharing has been in a time of transition since the 1990s, said Ribeiro. She traced the history of appropriation of resources without the fair sharing of benefit, which began with the adoption of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights by the World Trade Organization in 1994. The trend toward appropriation was then driven by the genomics revolution in the 1990s through the 2000s, the development of technology for sequencing and bioprospecting, and the emergence of open-access databases. Many patents have been filed by companies in developed nations over resources and knowledge about how to apply resources coming from LMICs. However, these were later viewed as acts of biopiracy that became regulated under the Nagoya Protocol,2 which was adopted in 2010 by the United Nations Environmental Programme at the Convention on Biological Diversity.

___________________

2 More information on the Nagoya Protocol can be found at https://www.cbd.int/abs (accessed March 3, 2020).

The Nagoya Protocol established two principles: (1) the principle that countries have sovereign rights to decide and regulate how genetic resources coming from their countries are accessed and used, and (2) the principle of reciprocity, which gives countries the right to ask for a share of the benefits—monetary or otherwise—resulting from the use of such resources. She explained that this process led to a polarization and crisis of trust between providers and users of genetic resources. Because microorganisms and pathogens are included in the scope of the Nagoya Protocol, it changed the way that pathogen resources are shared globally, Ribeiro said. This paradigm change was driven by a series of shifts from:

- physical to digital environments;

- informal sharing to formal and regulated sharing;

- sharing at the national and regional scope to global sharing;

- sharing in isolated expert networks to sharing in more integrated systems involving multiple disciplines and sectors; and

- bilateral collaboration to complex multilevel cooperation.

Barriers to Sharing Pathogen Sequence Data

In association with the European COMPARE project, Ribeiro and colleagues identified barriers to sharing pathogen sequence data across domains, countries, sectors, and institutions (Ribeiro et al., 2018a). By plotting the barriers across the knowledge-valorization cycle for initiatives and innovations to tackle infectious diseases, they found that the barriers extended beyond different discourses, hampering early phases of pathogen discovery as well as the development of basic public health research and response measures. She highlighted several of the more complex barriers to frame her discussion of practical tools to improve collaboration and data sharing. Barriers related to research include publication priority, organizations’ confidentiality, and insufficient compliance with ownership agreements. At the political and legal levels, barriers relate to countries’ economies, international treaties, government permission, notification processes, ownership agreements, and political willingness among LMICs.

Practical Tools to Foster Collaboration and Enhance Sharing

Ribeiro suggested several practical tools for fostering collaboration and enhancing data sharing. Outbreak-related data need to be available before they are published, which would benefit from fostering a culture of rapid prepublished data sharing as an integral part of public health research. Funders and academic publishers should recognize the diversity of contributions and push for rapid publication through fast peer-review systems, preprint

platforms, and alternative performance indicators for academic credit. Tools also need to be developed and implemented to improve coordination and establish trust, she suggested. To that end, database and collection curators should develop tools to build capacity, protect legitimate interests, and reinforce fair research collaborations.

For example, the COMPARE project has a database for sharing pathogen sequences and has established a pseudo-anonymized sharing platform in which it provides free and open access to analytical tools to help users interpret and use this data-building capacity. COMPARE has also experimented with different levels of access by providing private data hubs for users to share sensitive information with a selected group of stakeholders; after an agreed-upon duration, these data mandatorily go to the public domain. Ribeiro stated that the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data and the J. Craig Venter Institute have used access agreements to reinforce nonmonetary benefit sharing, in which users commit to engage in fair collaboration through co-authorships and acknowledgment of data providers.

Parallel legal databases and tracking systems have been useful for connecting shared materials and data with their legal documentations and conditions for use, she said. By providing transparency on rules and conditions, these can alleviate the demonstrative burden on users and help providers monitor access and benefit-sharing compliance. Blockchain-based systems have been used to link data, materials, and legal conditions, she added.

Developing Long-Term Policy and Legal Strategies

Ribeiro considered whether these practical tools are sufficient to solve the problems related to collaboration and data sharing to tackle microbial threats. Although these tools can alleviate some of the barriers, addressing the barriers’ root causes—which are usually political and legal in nature—requires long-term policy and legal strategy recommendations. She offered three suggestions for establishing governance and legal preparedness.

Ribeiro’s first suggestion was to define and clarify the scope of policies and regulations that govern data sharing. Discussions of global data sharing of pathogen resources often hinge on the scope and definitions of terms in the Nagoya Protocol (e.g., whether the term genetic resources includes only physical, biological materials or if the term also includes digital sequence data). She suggested that the focus of these discussions should shift from coverage issues to the effect of different modalities of implementation, given the importance of rapid access to sequence data in supporting outbreak research and response. The International Health Regulations also plays into these discussions. Although the framework determined that there is a need for rapid data sharing during public health emergencies of international con-

cern (PHEICs),3 it provides no specific guidance about which types of data should be shared, when they should be shared, or how they should be shared. The framework does not define the data-sharing obligations or establish a lower threshold for data sharing compared to a PHEIC. She suggested that obligations of rapid sharing should be established in advance.

Ribeiro’s second suggestion was to coordinate epidemic research and development to organize the response and support rapid product development. She noted how the 2014 to 2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa highlighted the importance of coordinated international response. Progress is being made under the World Health Organization (WHO) Blueprint Strategy, which is working with the Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations to connect affected countries with industry for rapid product development.

In the context of the One Health approach, she described the tripartite collaboration among WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and the World Organisation for Animal Health to develop top-down guidance on the national and community implementation of One Health surveillance responses. However, she noted that this type of coordination mechanism takes time to be activated in practice because it is difficult to align these different organizations, as demonstrated by the issues faced during the MERS outbreak.

Developing harmonized and preestablished rules and conditions for data access, sharing, and use was Ribeiro’s third suggestion. She explained that efficient data sharing requires harmonized systems based on simplified sharing agreements that have been established before times of crisis. The Network of International Exchange of Microbes under the Asian Consortium for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Microbial Resources has a memorandum of understanding for noncommercial use of genetic resources that is an example of successful harmonization, she noted. Under this memorandum of understanding, all members waive their individual access and benefit-sharing conditions for sharing their resources for noncommercial use. Similarly, WHO’s Pandemic Influenza Preparedness framework is multilateral and includes standard material transfer agreements to govern the sharing of materials for commercial use, which guarantees benefit sharing with industry (Ribeiro et al., 2018b).

___________________

3 She defined a PHEIC as an occurrence or imminent threat of an illness or a health condition, caused by bioterrorism, epidemic or pandemic disease, or a novel and highly fatal infectious agent or biological toxin that poses a substantial risk of a significant number of human fatalities or incidents or permanent or long-term disability.

Promoting Outbreak-Related Data Sharing

Ribeiro remarked that despite the broad support and recognition of the need for data sharing to support outbreak research, data sharing during PHEICs remains limited. Technology is being developed at a pace that exceeds the development of governance mechanisms to implement those technologies and assess their social and economic effects, which has hampered efforts to apply these technologies in the most effective way. She suggested several areas of focus and investment to improve outbreak-related data sharing. Open-access databases are needed for outbreak research and response, but investment should also be channeled into developing collaborative platforms with curation strategies to support fair research collaborations and address the concerns of different stakeholders. Investment should also support efforts to build sharing systems during “peace time” that are substantiated by clear governance and legal mechanisms that can be rapidly activated and scaled up during times of crisis. Finally, she suggested that the focus should shift from the practice of bilateral negotiations toward global, harmonized, and preestablished systems for sharing pathogen resources that can support the timeliness and efficiency needed to support outbreak response.

ADDRESSING HEALTH CHALLENGES WITH BEHAVIORIAL INSIGHTS AND TOOLS

Fadi Makki explored strategies for applying insights from behavioral sciences to enhance acceptability and adoption of innovations across diverse social and cultural contexts. He described how behavioral insights can inform complementary tools to address health challenges using the example of a measles vaccination field experiment conducted in Lebanon.

Applying Evidence from Behavioral Science to Public Policy

Makki maintained that biases and other psychological determinants of health behavior need to be considered more thoroughly in order to apply behavioral insights to address health challenges, including microbial threats. Behavioral insights can offer complementary tools to health policy makers, he added. Evidence from behavioral science shows that decisions are not often deliberate or considered but automatic and influenced by context—that is, people do not make decisions in a straightforward way. He explained that among the psychological determinants involved in the processes of thinking, deciding, and taking action are misunderstandings, social pressure, information overload, overconfidence, procrastination, problems with willpower, forgetfulness, and inconvenience. One approach used to understand the biases and heuristics involved in decision making is dual system

theory (Kahneman, 2003). Within this theory, system 1 thinking is faster and often used to make habitual decisions; this type of thinking is prone to error. System 2 thinking, which is used to make more complex decisions, has been described as a “lazy controller.” He explained that the majority of thinking (approximately 90 percent) involves system 1, which he likened to cruise control.

Public policy often assumes that people tend to operate primarily with system 2 thinking to make decisions, said Makki. However, this assumption is being dispelled by a growing body of literature in psychology, economics, and public policy. The development of public policies has been dominated by tools that are based on rational assumptions that people are system 2 operators. These traditional tools fall along a spectrum with command-and-control approaches on one end, rewards and incentives on the other, and the basic provision of information in the middle. He explained that command- and-control approaches rely on sanctions and penalties, which do not always work, while the use of rewards and incentives is not a sustainable approach.

The basic provision of information relies on assumptions that people have greater cognitive processing power than they actually do. However, policy makers can avail themselves of complementary tools anchored in behavioral insights that can be helpful, said Makki. For instance, the concept of “nudging” is a behavioral insight tool that refers to “any aspect of choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives” (Thaler and Sunstein, 2009). He suggested that applying these types of behavioral insights from multidisciplinary research in fields such as economics, psychology, sociology, cognitive science, and neuroscience is relevant to all policy areas and can be used to inform better understanding about how humans behave.

Using Behavioral Insights to Address Health Challenges: Example from Lebanon

Behavioral insights can be used to address health challenges by exploring the behavior of individual patients and their families. Makki explained that behavioral bottlenecks exist at every level of the behavioral change pathway—prevention, early detection, and treatment—and are encountered by every stakeholder in the value change. He explained that these bottlenecks can be addressed through a two-step process. The first step is to review biases through a behavioral lens by evaluating psychological determinants. The second step is to use experiments to test approaches to changing behavior, ideally with randomized controlled trials.

To illustrate this process, Makki described a randomized controlled trial conducted in Lebanon to increase uptake of the measles vaccine during an

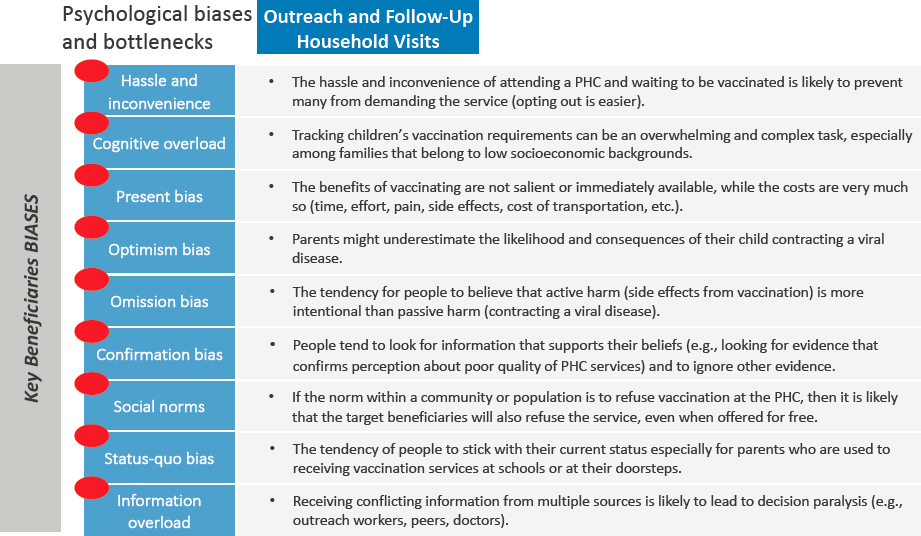

outbreak. As part of the study, they evaluated the challenges and biases that affect individuals’ decisions about vaccination and developed solutions to address some of these challenges and biases to shape people’s behavior, he said. Figure 4-1 provides a list of psychological biases and bottlenecks they identified during this process. For instance, present bias makes the benefits of vaccination less salient or immediately available, while the costs, side effects, pain, effort, and inconvenience of vaccination are immediate. Optimism bias can cause parents to underestimate the consequences of their child contracting a viral disease. He noted that the status quo bias was especially relevant for parents who were used to receiving vaccination services at school or at their doorstep.

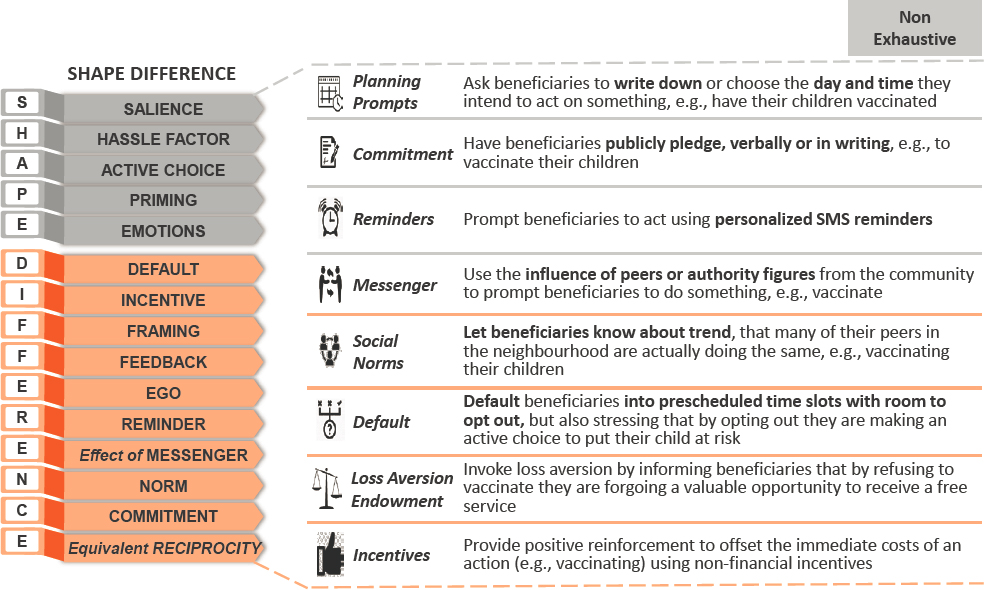

Other challenges identified during the trial included neglect, forgetfulness, previous bad experiences with primary health care, lack of awareness, and perceptions of low quality. Many of these challenges and biases have behavioral roots that can be countered by different types of interventions. Makki and colleagues created the SHAPE DIFFERENCE strategy to develop and test various interventions that are informed by behavioral insight tools (see Figure 4-2). For example, planning prompts ask beneficiaries to write down or choose the day and time they intend to act on something, such as having their children vaccinated. Making a public commitment, receiving reminders, and social norms can also have an effect on behavior. He noted that “default” is among the most powerful nudges. This can be used by defaulting beneficiaries into prescheduled time slots with an opportunity to

NOTE: PHC = primary health care.

SOURCES: Makki presentation, December 4, 2019; B4Development and Nudge Lebanon team analysis.

SOURCES: Makki presentation, December 4, 2019; B4Development and Nudge Lebanon team analysis.

opt out, while also emphasizing that opting out is making an active choice to put the child at risk.

Findings and Lessons Learned from the Measles Vaccination Field Experiment

To evaluate the benefits of SHAPE DIFFERENCE behavioral insights, Makki and colleagues developed a test calendar, comprising five nudges and behavioral tools; this calendar was used in 6,160 households across three areas of Lebanon, Makki explained. The calendar was designed to counter the negative influences of peers, the discontent from receiving the same services as refugees, neglect, intention–action gap, forgetfulness, lack of trust in the quality of vaccines at the primary health center, and the lack of awareness that vaccination is free. For example, based on the social norms insight, the calendar informs beneficiaries that more than 90,000 children have already been vaccinated free of charge. The calendar uses social endorsement and commitment by informing beneficiaries that their neighbors are protecting their children by vaccinating them and asking beneficiaries to check a box promising to vaccinate their own children. The calendar again uses the commitment insight by asking beneficiaries to put a nonbinding sticker on the calendar marking the day they will bring their

children to be vaccinated. The intention of this aspect of the implementation is to bridge the intention–action gap by prompting beneficiaries to mark a day on the calendar.

Finally, the calendar uses the effect of messenger insight by displaying the seal of the Ministry of Health. This insight was used to address the fact that many people thought the vaccinations delivered at primary health centers were of low quality. Use of the calendar during this trial led to a 50 percent increase in the likelihood of vaccinating relative to the control group that did not receive the calendar, Makki reported. The probability of a household vaccinating at least one child was 6.8 percentage points greater among the treatment group households (20.3 percent) than the control group households (13.5 percent). In terms of vaccination uptake by visit type, uptake was 5.7 percentage points greater among the treatment group than the control group via outreach and 9.3 percentage points greater among the treatment group versus the control group via follow-up.

Makki provided an overview of lessons learned from the experiment. The first was that applying the same solution to different populations will produce different results. Non-Lebanese beneficiaries were more likely to trust that the vaccines offered by primary health centers were truly free and were 4.4 percentage points more likely to vaccinate their children than Lebanese households. It is also necessary to develop a proper understanding of the target population and the behavioral challenges deterring them from acting on their intentions. Using the behavior change tools in the calendar, Makki and colleagues identified common recurring problems among their participants. However, he cautioned that the use of behavioral insights does not represent a perfect solution to structural problems, but rather complements conventional procedures.

In the case of the measles vaccination experiment, the majority of households involved in the experiment remained unvaccinated; although the treatment led to measurable improvement, it did not solve the problem of undervaccination. Lastly, he observed that offering the same message repeatedly did not necessarily lead to higher uptake. Multiple outreach visits can increase uptake but only if coupled with new offerings. In this case, households receiving the calendar during a follow-up visit were 9.3 percentage points more likely to vaccinate compared to those that did not.

Apply Behavioral Insights to Other Stakeholders to Counter Microbial Threats

Makki explored the need to focus on other stakeholders when applying behavioral insights to the area of microbial threats. Focusing exclusively on individual behavior does not account for the behavior of other stakeholders in the value chain, such as industry, policy makers, and health care providers.

Behavioral insight tools can also be used to nudge these other stakeholders into a course of action. To illustrate the application of these insights to addressing antimicrobial resistance, he described how behavioral insights can be used to counter the overprescription of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a key threat to global health, with many infections becoming more resistant to treatment as antibiotics become less effective; health care systems also face mounting costs as a result of antibiotic misuse and overuse.

He highlighted several behavioral insight tools that can be used to help address this issue. Social norms are commonly used to discourage overprescription of antibiotics by comparing physicians’ rates of prescription. For example, an intervention in the United Kingdom sends personalized letters to the most overprescribing physicians to inform them that 80 percent of doctors prescribe fewer antibiotics. These letters were sent by the UK Chief Medical Officer, using the effect of messenger, another behavioral insight tool. These letters were associated with a significant drop in the prescription of antibiotics, he said (Hallsworth et al., 2016).

To use the commitment tool, another intervention hung poster-sized letters in exam rooms for 3 months that included photographs and signatures of doctors who committed not to prescribe antibiotics unnecessarily. The intervention group decreased their antibiotic prescribing rates by 9.1 percent, while the control group’s prescribing rate increased by 9.2 percent (Meeker et al., 2014). Hand hygiene is another area in which behavioral insights can be used to counter hospital-acquired infections and antimicrobial resistance, he added.

Advancing the Application of Behavioral Insights

Makki concluded with a set of takeaway messages and potential avenues for applying behavioral insights to counter antimicrobial resistance. Expectations must be managed, he said. The power of behavioral insights has become increasingly recognized in recent years, but behavioral insights are not a panacea. In some cases, more traditional regulation- or incentive-based tools will still be needed. Behavioral insights should be treated as complementary tools, rather than strict alternatives. He noted that context matters—what works in one place will not necessarily work in another place, which underscores the need to test tools and experiment using rigorous evaluation methods.

Scaling up the use of behavioral sciences in public policy and health policy through capacity building across all stakeholders in the health care value chain will allow for more opportunity for cocreation, he suggested. Behavioral insights courses are being taught to new civil service graduates; health care providers would benefit from being taught about them as well. He added that social norms are a powerful tool, but dynamic social norms

are even better. Dynamic social norms inform beneficiaries that the norm is trending upward, which has a larger effect in terms of updating peoples’ beliefs and countering fake news. Makki and colleagues are working to create a game to inoculate people against fake news related to vaccines, for example.

DISCUSSION

Eva Harris opened the discussion by reflecting on each of the presentations. She remarked that Osewe illustrated the benefits of creating a straightforward platform to support health workers on the ground in LMICs, as well as providing population-wide analytics; he also underscored the challenge of how to foster local-level innovation in the face of competition from innovations developed by larger international organizations that may not be suited to local needs. She highlighted Bird’s focus on the local community being a key stakeholder in the uptake of epidemic response activities, as evidenced by the Ebola outbreak, and on the need to understand and adapt to local cultural contexts. Harris commented that Ribeiro’s presentation showed why practical tools to foster collaborations need to be put in place ahead of, during, and after the public health emergencies. Makki’s presentation elucidated how behavioral tools can be experimentally applied to change behaviors, said Harris, which offers a potential strategy for dealing with health issues such as loss of confidence in vaccines in a culturally respectful way.

Matthew Zahn, medical director, Division of Epidemiology and Assessment, Orange County Health Care Agency, asked if data sharing has actually improved over the past decade. Ribeiro responded that the question reveals a common sentiment across researchers in this area that these issues are too complex to resolve. Although there have been successful systems at a small scale or tackling specific resources, much progress remains to be made toward an overarching solution. However, she noted progress over the past decade in how data are shared, as evidenced by gene banks, global networks, and discussions under way at WHO, at the Convention on Biological Diversity, and in regional networks such as the European Commission. Harris pointed out that discussions at the organizational level may not include in-country interaction. Ribeiro replied that these discussions are centered at a political level; more engagement is needed with researchers who share data, use data, and coordinate the response.

Maurizio Vecchione, executive vice president of Global Good and Research, Intellectual Ventures, asked Bird to expand on the communication strategies used to share public health information about the Bombali and Marburg viruses with local communities as well as internationally. Bird replied that decisions about how to handle this type of information are complicated and political, because they are determined by the situation and

setting. If a virus is found that is closely related to known pathogens, that information must be disseminated, which has ramifications for people on the ground.

In a small country like Sierra Leone, it is easier to access the president or the minister of health than in a country like Tanzania, he added. When they found the Bombali virus, it was challenging to convince governments of countries to take the threat seriously and develop a rational response, which he attributed in part to the psychological ramifications of the recent Ebola outbreak. Over a period of a few weeks, however, they were able to work with government colleagues (including the highest-level officials) to develop the communication materials to deliver to communities. He noted this strategy was in keeping with the ethos of the PREDICT project of making a country’s priorities superordinate to a program’s priorities. This process of communication and activating a response is more immediate and straightforward for a virus like Marburg, which is a known human pathogen, noted Bird.

In contrast, after the discovery of the Bombali virus they encountered some resistance from the academic community, despite concrete laboratory confirmation of the existence of the virus, about whether to tell the public immediately or to wait for a peer-review process to publish a paper. With the government’s support they decided to go ahead and release information in the country, which included visits to local communities. He commented that the community level should not be overlooked in discussions about data sharing, particularly in the context of sharing information about high-consequence pathogens at the village level. For instance, his group has developed a “bat book” to inform people in their local language about how to co-exist safely with bats, who are good for the environment but sometimes carry viruses or pathogens that harm humans.

George Haringhuizen, coordinating advisor and senior legal counsel, Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, commented that his group has convened many workshops with hundreds of scientists, asking what they would do if they were to discover a new pathogen, in terms of reporting to the government or going for publication. He said that more than half of those scientists said they would go immediately for publication to disseminate the information, while the remainder said governments should be informed so they can manage the possible outbreak. Haringhuizen commented that the approach described by Bird showed how the community can be engaged in research and development of an outbreak response.

Greg Armstrong said that Bird made a good case for having a process in place to deal with the discovery of previously unknown viruses not yet found in humans. He asked how researchers might prepare in advance for transmitting these types of results. Bird responded that it should be part of the scientific culture to determine in advance how to deal with the discovery

of an infectious pathogen. He pointed out that such discoveries are like a microcosm of an outbreak in terms of the urgency to plan, to find partners, and to identify key players in the country—these steps can be taken in advance of initiating a research project. He described Ebola as the acid test of a worst-case pathogen discovery effort because “Fearbola is bigger than Ebola.” To mitigate these issues, he suggested working from the outset of a project with government colleagues at all levels to ensure they understand the potential ramifications for the community, country, and region, including trade implications. For example, veterinary diseases can have substantial regulatory and economic implications. He suggested that to err on the side of caution, any new pathogen should be considered a potentially robust human pathogen until proven otherwise.

Rafael Obregón asked about how to integrate behavioral tools into disease outbreak response, because many community engagement interventions are setting specific and not easily replicable. Makki responded that context does matter and that experiments cannot be replicated exactly, but lessons can be gleaned from previous work when implementing in a new setting in order to further refine and improve the experiment. He suggested that capacity building and integrating behavior science at every step could help support efforts to scale up interventions more broadly. This effort would also benefit from educating more stakeholders—including policy makers, health care providers, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)—about the advantages of applying behavioral science and incorporating it into their work.

Harris asked Osewe about barriers they encountered as a local NGO trying to bring their innovation into practical use in the clinics and beyond. Osewe responded that in his experience, innovation is about creating value in addressing the real challenges that people are facing on the ground. Their platform was more readily accepted by end users because they had involved them in designing the concept, technology, and infrastructure. He added that partnership is also critical for scaling up. He suggested that the first phase of rolling out an innovation should involve engaging with decision makers, hospital and clinic managers, and volunteers to obtain buy-in and promote scalability.

Jonathan Towner asked about how to manage sample sharing for pathogens such as Ebola, which have biosecurity and safety concerns. He suggested that bilateral agreements might be an efficient way to get samples out of insecure areas. Ribeiro responded that infectious diseases do not respect boundaries and require global collaboration for the response, which necessitates continued international support for storing samples and developing countermeasures. She suggested moving forward initially by building local capacity to store and analyze samples. In terms of global sharing, she noted that bilateral negotiations are complicated, especially when they occur in times of crisis. Ideally, harmonized international agreements would be

developed at the global level with conditions that are equal for every country, she said.

Reflections on Day 1 of the Workshop

Kent Kester, vice president and head, translational science and biomarkers, Sanofi Pasteur, closed the first day of the workshop by highlighting what he considered to be a set of recurring issues discussed by various speakers:

- The metrics for success for new discoveries and approaches used in academia are often discordant with translational success in terms of deployment, implementation, or changes in policy and practice that make a difference in people’s lives.

- Substantial gaps remain in implementation and sustainability. Strong pilot projects and promising developments in vaccines and therapeutics often stall because they do not have the activation energy to be implemented sustainably at large scale, owing to a host of barriers that are difficult to overcome.

- Better strategies are needed to understand, build trust, and foster engagement with communities in the realms of research, outbreak response, and delivery of new technological approaches.

- Demonstrating value across health, financial, and social dimensions can help to accelerate the implementation of innovative projects.

- Innovative approaches should strive to be transversal, with connectivity across a range of problem areas; for example, mobile health apps could be designed to manage a range of diseases instead of just one.

- Data sharing is complicated by a host of factors—from national sovereignty to intellectual property to monetization of data—but these issues must be resolved, because infectious diseases do not respect country boundaries.

- Behavioral sciences can offer insights into how to engage with stakeholders and communities to facilitate the uptake of innovations in supportive rather than directive ways.

This page intentionally left blank.