3

Conclusions and Recommendations

Chapter 2 contains the committee’s detailed comparison of the Planetary Protection Independent Review Board (PPIRB) report1 findings and recommendations against the 2018 report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Review and Assessment of Planetary Protection Policy Development Processes2 (hereinafter the “2018 report”). This chapter presents the committee’s overall conclusions and recommendations to NASA that emerge from this comparison. The chapter begins by identifying three items:

- The main areas of consistency between the PPIRB and 2018 reports;

- The main areas of inconsistency and concern; and

- Issues raised in the PPRIB report, but not in the 2018 report, that deserve attention.

Then, the committee highlights three priorities in planetary protection that require action and makes recommendations for how NASA and its partners in the federal government can address these urgent needs. The chapter concludes by recommending that NASA implement, as soon as possible, new approaches to planetary protection in an initiative on small satellites, such as CubeSats.

AREAS OF CONSISTENCY

The majority of findings and recommendations in the PPIRB report are consistent with the 2018 report. The consistencies highlight issues in planetary protection policy that many stakeholders recognize as important, and the committee commends the authors of both reports for reinforcing these important aspects of planetary protection.

Both reports recognized that consideration of forward and back contamination is essential for protecting Earth’s biosphere and enabling future astrobiology studies and is integral for government and private-sector missions undertaken by all spacefaring nations. Achieving this objective, both reports emphasized, requires U.S. leadership and international cooperation. The reports highlighted the important role COSPAR has played in fostering

___________________

1 Planetary Protection Independent Review Board (PPIRB), NASA Planetary Protection Independent Review Board (PPIRB): Report to NASA/SMD: Final Report, NASA, Washington, D.C., 2019, https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/planetary_protection_board_report_20191018.pdf.

2 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), Review and Assessment of Planetary Protection Policy Development Processes, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2018.

international cooperation on planetary protection, with the PPIRB noting, for example, that “COSPAR [planetary protection] guidelines have evolved to be an internationally recognized, voluntary standard for protection of scientific interests in celestial bodies” that all spacefaring nations have used to inform compliance with the Outer Space Treaty (OST).3

The PPIRB and 2018 reports agreed that developments in science, technology, and private-sector space activities are changing the environment for the development and implementation of planetary protection policy. These developments include progress on a robotic Mars sample return mission, growing interest in low-cost, small satellite capabilities, accelerating plans to put humans on the Moon and Mars, and advanced mission planning for exploring ocean worlds, such as Europa, Titan, and Enceladus, with a variety of missions including orbiters and landers.

In light of this changing environment, both reports emphasized the need for NASA to reassess planetary protection policy frequently in light of new scientific information, technological developments, and government or private-sector space activities. The reports supported NASA’s decision to relocate the Office of Planetary Protection (OPP) from the Science Mission Directorate (SMD) to the Office of Safety and Mission Assurance (OSMA), and the PPIRB report praised NASA’s efforts to improve the OPP’s “communication, clarity, and responsiveness.”4 Looking ahead, the reports identified needs to undertake the following actions:

- Conduct biological and genomic research to explore better ways to characterize bioburdens on spacecraft;

- Develop new technologies for reducing the bioburden on spacecraft and evaluating samples returned from solar system bodies;

- Engage in more research on the probability of the survival and transport of terrestrial organisms in extreme space environments; and

- Develop better methodologies for awarding planetary protection credits for time spent in harsh space environments.

The PPIRB and 2018 reports also aligned in advocating for the expeditious development of new planetary protection policy specifically applicable for human missions. Both reports agree that existing planetary protection policy does not provide appropriate guidance for human missions. Developing planetary protection for human missions requires funding research to produce the scientific and technological information needed to formulate planetary protection policy applicable to human missions. For example, developing the idea of “exploration zones” on Mars into a more serious concept for human missions requires research on, among other things, the likelihood that biological contaminants released in the course of human activities would be transported to other areas of Mars.

The PPIRB and 2018 reports emphasized that mission success depends on developing and applying clear and complete planetary protection requirements early in mission development in order to reduce costs, inefficiencies, and delays—whether NASA or a private entity operates the mission. These requirements, the reports agreed, cannot prescribe how missions achieve compliance. Rather, mission designers are encouraged to innovate and use systems-engineering approaches to meet the necessary requirements.

Finally, the PPIRB and 2018 reports both stressed the need to develop a formal advisory process that provides the broad community of stakeholders with the opportunity to advise NASA on emerging scientific, technological, commercial, legal, and international issues. All such inputs are important for ensuring that planetary protection policy continues to support robust exploration and other uses of space in a rapidly changing context for space activities.

AREAS OF INCONSISTENCY AND CONCERN

In comparing the PPIRB and 2018 reports, the committee identified two major issues on which the reports diverge and one issue where the two reports highlight in different ways contexts in which government and private--

___________________

3 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Finding [18].

4 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Finding [8].

sector stakeholders confront a lack of clarity about the development, application, and implementation of planetary protection policy.

First, the PPIRB found that adherence to COSPAR guidelines constitutes one “mechanism for establishing compliance with Article IX” of the OST and that “other mechanisms that may be more appropriate also exist.”5 The PPIRB recommended that the U.S. government use the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) as an alternative mechanism for international cooperation on planetary protection policy.6 The PPIRB report provided no supporting information or analysis for why the PPIRB recommended that the U.S. government shift its international participation in planetary protection policy development from COSPAR to COPUOS. By contrast, the 2018 report did not discuss any other mechanism other than COSPAR as the main forum for the U.S. government’s involvement in international cooperation on planetary protection. The 2018 report focused on ways that NASA and other parts of the U.S. government could support ongoing efforts to improve COSPAR as an international forum for discussing planetary protection issues and developing science-based guidance on planetary protection for spacefaring nations. The 2018 report noted that COPUOS itself, in 2017, identified “COSPAR as the appropriate international authority for creating consensus planetary protection guidelines.”7

Second, the PPIRB and 2018 reports did not align on how the OST becomes legally relevant for nongovernmental entities. The PPIRB heard briefings on this issue that presented different perspectives, and, based on these presentations, the PPIRB took no position on what it heard, finding instead that “[t]here is a lack of consensus as to how and when the OST has legal relevance to non-governmental entities.”8 The 2018 report focused on how the OST clearly requires states parties to make the planetary protection provisions in Article IX legally relevant for nongovernmental entities by fulfilling their obligation under Article VI to authorize and continually supervise the space activities of nongovernmental entities. The 2018 report located legal problems at the level of national rather than international law in analyzing the “regulatory gap” in U.S. federal law on planetary protection and private-sector space activities. The differences between the two reports on this issue highlight confusion and a lack of clarity about how the U.S. government fulfills its Article VI and IX obligations under the OST through federal law applicable to the space activities of nongovernmental entities.

Third, the PPIRB and 2018 reports focus on the new challenge of implementing science-based planetary protection policy within private-sector space initiatives and missions. In various places, the PPIRB report reflected concerns that implementation of planetary protection policy might constrain private-sector innovation and impede the U.S. government’s policy of encouraging commercial exploration and uses of space.9 The 2018 report described the importance of U.S. leadership in ensuring that planetary protection policy is based, first and foremost, on the best available scientific evidence relevant to forward and back contamination.10 Both reports stress that the same planetary protection measures apply equally to both government and private-sector space activities. Rather, together, the two reports underscore in different ways that NASA and the U.S. government have not yet constructed a planetary protection policy process that aligns the needs of science and the private sector in ways that appropriately foster space exploration and commercial uses of space.

NEW TOPICS FOR CONSIDERATION

The PPIRB report discussed a number of topics not addressed in the 2018 report, and the committee agrees that these topics deserve attention in planetary protection policy. To begin, the PPIRB offered findings and recommendations focused on the need to re-examine the planetary protection categorization of missions to the Moon, Mars, and small solar system bodies, such as asteroids.11 The PPIRB also explored whether minimum, base costs

___________________

5 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Finding [18].

6 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Recommendation [34].

7 See NASEM, 2018, p. 11.

8 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Finding [73].

9 See, for example, PPIRB report, Major Recommendation [54].

10 See, for example, NASEM, 2018, p. 39.

11 See PPIRB, 2019, starting at Major Finding [35] and through to Supporting Finding [40]. Small bodies refers to planetary bodies, including asteroids, comets, Kuiper Belt objects, and dwarf planets.

of complying with planetary protection requirements would adversely affect the feasibility of missions using small, inexpensive spacecraft.12 The PPIRB expressed interest in NASA providing technical information or assistance on planetary protection to private-sector entrepreneurs.13 Further, the PPIRB report identified problems arising from the SpaceIL incident and made recommendations to prevent those problems for impeding commercial space activities.14

The PPIRB also reached conclusions on another topic not considered in the 2018 report, but with which the committee does not agree. The PPIRB supported the idea that the presence of martian meteorites on Earth can inform how samples of martian material returned from Mars are handled. As the committee discussed in Chapter 2 with respect to Major Finding [60] and Major Recommendation [61] in the PPIRB report, arguments that NASA can relax planetary protection requirements for Mars samples brought to Earth are not scientifically persuasive to this committee.

STRATEGIC FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From its comparison of the PPIRB and 2018 reports and its examination of the topics considered only in the PPIRB report, the committee has identified three areas of strategic importance for planetary protection policy common to both reports on which it makes specific findings and recommendations:

- The need to establish a new advisory process for the development of planetary protection policy;

- The need to clarify the legal and regulatory framework applicable to private-sector space activities that implicate planetary protection; and

- The need to improve the scientific and technological foundation of planetary protection policies for the human missions to Mars.

Establishing a New Advisory Process for Planetary Protection Policy

As the PPIRB and 2018 reports highlight, the context for planetary protection policy has gained new dimensions and is becoming increasingly complex. These developments create the need to engage new stakeholders in the development and implementation of planetary protection policy in order to ensure that NASA formulates policies with comprehensive input and communicates the policies effectively to all the communities affected.

Seven findings and recommendations in the PPIRB report refer to the importance of engaging the planetary protection stakeholder community by means of a regular, formal advisory process.15 The 2018 report emphasized that a key means to secure stakeholder engagement is through advisory groups, and it strongly recommended an advisory group that could provide ongoing review of planetary protection policies. As stated in the 2018 report, the advisory body will:

- Serve as a sounding board and source of input to assist in development of planetary protection requirements for new missions and U.S. input to the deliberations of COSPAR’s Panel on Planetary Protection;

- Provide advice on opportunities, needs, and priorities for investments in planetary protection research and technology development; and

- Act as a peer review forum to facilitate the effectiveness of NASA’s planetary protection activities.16

The committee supports the findings and recommendations in both reports that focus on the need for a new advisory process on planetary protection policy. Indeed, the committee agrees that many of the PPIRB’s concerns about participation in the policy-making process could be addressed, if not ameliorated, through a stakeholder

___________________

12 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Finding [28] and Supporting Recommendation [29].

13 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Recommendation [12].

14 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Finding [30].

15 Two prominent examples are Major Recommendations [6] and [7].

16 See NASEM, 2018, p. 92.

forum charged to examine the planetary protection issues and make recommendations to decision makers in the U.S. government.

Finding: The PPIRB and 2018 reports, independently and together, make the persuasive case that NASA establish a new process for gathering input from the community of relevant stakeholders to ensure that the planetary protection policy comprehensively reflects the new environment of public and private space activities, contributes to the success of government and private-sector space missions, and reinforces U.S. leadership on planetary protection.

Recommendation: NASA should establish a new, permanent, and independent advisory body formally authorized to provide NASA with information and formulate advice from representatives of the full range of stakeholders relevant to, or affected by, planetary protection policy.

Attributes of a New Approach to Advise and Review

NASA and the National Academies are adept at establishing advisory bodies for various scientific, project review, advanced technology, and related purposes. Even so, creating an advisory body tasked with providing input on all aspects of planetary protection poses a challenge because of the legal, scientific, public policy, commercial, and public health issues involved. Given the very broad scope of potential advisory issues to be considered (ranging, for example, from establishment of Mars exploration zones, to guidelines for quarantine facilities and protocols, to approaches for international policy coordination), an effective advisory process might actually consist of more than a single committee or panel. The following sections deal with key aspects of a new advisory process.

Inclusion of All Stakeholders

In view of the scope of the advice required, NASA will need to ensure that the new advisory process includes representatives from all relevant stakeholder communities, especially given that subsections of the same community may hold opposing views on some topics. In addition, NASA will have to be proactive in keeping the appointed representatives engaged in the advisory process. The 2018 report noted that some past advisory bodies suffered from inadequate participation by stakeholders.17 To mitigate this problem in the future, the committee suggests that senior levels of the convening authority establish the charter and requirements for the advisory body. Wide circulation of the terms of reference for this new advisory body among relevant stakeholder communities will promote “buy in” by the various constituencies.

Initial Focus of the Advisory Committee

During the committee’s review, all three of the major stakeholder communities (science, human exploration, and private-sector space) communicated a sense of urgency, driven by factors such as the following:

- Plans to launch the first element of the Mars sample return campaign in July 2020;

- An administration directive to return to the Moon in 2024 and then go on to Mars; and

- Private entities developing plans for human Mars exploration and demonstrating capabilities for deep space launching.

Given the urgency of this activity, the committee sees advantages for this new advisory body to begin addressing the issues outlined above. While, some, if not all, of them have international ramifications, all have strong implications for near-term activities by NASA and other U.S.-based entities and organizations. Therefore, prompt U.S. action is needed in the near future. Adopting this approach is not only consistent with the U.S.’s traditional

___________________

17 See NASEM, 2018, p. 63.

role in the development of planetary protection policies, but also addresses the clarity of authority desired by the private sector. The committee does recognize a need for COSPAR participation, and the committee fully anticipates that a new advisory group will share and exchange any relevant decisions, findings, or recommendations with COSPAR. It is in NASA’s best interest that international partners are fully aware of U.S. efforts to modernize and improve planetary protection policy.

Finding: The execution of planetary protection policy necessarily requires international coordination. However, the United States has shown leadership in developing planetary protection policy and most, if not all, of these policies have been adopted internationally. However, there are U.S. issues that require immediate attention.

Recommendation: The initial focus of the new advisory body should be on the needs of upcoming private sector and government missions.

To summarize, there are many vexing issues identified by the PPIRB and 2018 reports that can be addressed through a properly constituted and chartered review and advisory process that engages all planetary protection stakeholders. Such an effort will go far toward providing the transparency that some thought was lacking in previous reviews of planetary protection.

Clarifying Legal and Regulatory Issues Concerning Planetary Protection

A second strategic challenge identified in the PPIRB and 2018 reports involves issues with the international and national legal and regulatory frameworks applicable to the planetary protection aspects of private-sector space activities. More specifically, these issues arise in connection with private-sector activities undertaken without contracts with NASA. When NASA provides support to a private-sector activity, the requisite contract typically includes requirements for the private-sector partner to implement NASA’s planetary protection measures. In connection with planetary protection, the committee is concerned that a lack of clarity persists about the obligations of the United States under the OST and how federal law applies to private-sector space activities implemented independent of NASA involvement. Such uncertainty stands in the way of a clear and authoritative legal and regulatory framework for private-sector space missions that implicate planetary protection requirements.

International Law: The Outer Space Treaty, Planetary Protection, and Private-Sector Space Activities

At the level of international law, the PPIRB and 2018 reports described debates about how the United States, as a state party to the OST, is required to comply with its obligation to authorize and continually supervise planetary protection aspects of the space activities of nongovernmental entities.18 In its review of the OST and the debates surrounding it, the 2018 report concluded that “states parties have a clear obligation under Article VI of the OST to authorize and continually supervise the space activities of non-governmental entities,” which is an obligation that encompasses authorization and supervision of such activities that implicate a core aspect of Article IX of the treaty—planetary protection.19 The PPIRB heard conflicting presentations on the OST and took no position, merely noting that “[t]here is a lack of consensus as to how and when the Outer Space Treaty has legal relevance to non-governmental entities.”20

The committee agrees with the conclusion reached by the 2018 report. However, based on the views presented to the PPIRB, the committee acknowledges that disagreements continue about how the United States will comply with its obligations under the OST concerning the planetary protection aspects of private-sector space activities not involving NASA participation.

___________________

18 Outer Space Treaty, Articles VI and IX.

19 See NASEM, 2018, p. 15.

20 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Finding [73].

Finding: The persistence of disagreements about how the United States fulfills its obligations under the OST in connection with private-sector space activities that implicate planetary protection creates uncertainty for the private sector and potentially harms the objective of the U.S. government to facilitate exploration and uses of space by the private sector.

Recommendation: NASA should work with other agencies of the U.S. government, especially the U.S. Department of State, to provide the private sector with a clear and authoritative explanation of the U.S. government’s obligations under the Outer Space Treaty to authorize and continually supervise the space activities of nongovernmental entities that raise planetary protection issues.

Domestic Law: Legal Authority, Substantive Rules, and Enforcement

The PPIRB and 2018 reports identify problems with how U.S. federal law applies to the planetary protection aspects of private-sector space activities undertaken without NASA participation. The 2018 report found that “[a] regulatory gap exists in U.S. federal law and poses a problem for U.S. compliance with the OST’s obligations on planetary protection with regard to private-sector enterprises.”21 Although the PPIRB report did not use the term “regulatory gap,” the chair of the board confirmed to the committee that the legal and regulatory issues addressed at various points in the PPIRB report were equivalent to the regulatory-gap problem identified by the 2018 report.22 Uncertainty about how U.S. federal law applies to the planetary protection aspects of private-sector space activities creates unneeded and potentially costly confusion that does not advance the U.S. government’s and NASA’s strategy of encouraging private-sector exploration and uses of space.

Congress has granted the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) the legal authority to approve the launch of vehicles and payloads into space from the United States and their re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. With companies developing plans for new types of space activities, such as commercial lunar missions or human missions to Mars, the FAA confronted the question of whether its legal authorities included the power to regulate private-sector activities for planetary protection purposes. The 2018 report noted that “[i]n reviewing private-sector plans for lunar missions,” the FAA “tested the scope of its regulatory authority, leading it to conclude that the FAA might need additional authority to evaluate future missions in order to ensure the United States complies with the [Outer Space Treaty].”23 In addition, the 2018 report stated that “there is no explicit legislative or executive guidance about whether FAA’s spacecraft reentry licensing authority extends to review or approval of plans to prevent back contamination from sample return missions.”24 The PPIRB report found that various licensing mechanisms, including the FAA’s launch and re-entry approval authorities, “could be improved to relieve administrative burdens and address misperceptions of legal uncertainty for private sector space activities, including private sector robotic and human planetary missions that do not have significant NASA involvement.”25

In a presentation to the committee, a representative from the FAA stated that the agency had sufficient authority in its launch and re-entry licensing power to evaluate and regulate the planetary protection aspects of private-sector space missions conducted independent of NASA.26 The statements from the FAA representative appear to clarify the FAA’s present position that it has clear and sufficient legal authority to vet the planetary protection aspects of vehicles and payloads under its power to license launch and re-entry activities and conduct payload reviews for private-sector actors. However, in exercising this authority, the FAA apparently can accept or reject NASA advice on planetary protection. This situation leaves an applicant for a license potentially uncertain as to what planetary protection standards the FAA will apply in reviewing the proposed mission. The possibility that the FAA could approve a license under planetary protection standards that do not conform to NASA’s measures could create

___________________

21 See NASEM, 2018, p. 88.

22 Conference call between PPIRB Chair S. Alan Stern and the committee on December 16, 2019.

23 See NASEM, 2018, p. 87, footnote 6.

24 See NASEM, 2018, p. 70.

25 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Finding [53].

26 Briefing to the committee by C. Philip Brinkman, senior technical advisor, Licensing and Evaluation Division, FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation, November 21, 2019.

problems for the principle supported by the PPIRB and 2018 reports that government and private-sector missions be held to the same planetary protection standards.

The FAA representative’s statement to the committee about the FAA’s legal authority to evaluate planetary protection issues in licensing activities does not address another aspect of the regulatory gap—the lack of clear legal authority concerning the authorization and supervision of post-launch, on-orbit activities undertaken during private-sector space missions. The 2018 report stated that “[n]o federal regulatory agency has the jurisdiction to authorize and continually supervise on-orbit activities undertaken by private-sector entities, including activities that could raise planetary protection issues.”27

After publication of the 2018 report, an incident involving planetary protection and the private sector occurred that underscored the uncertainties surrounding federal law in this area. As the PPIRB report discussed, the owner of a payload allegedly did not inform the launch provider that the payload contained biological materials.28 The disclosure of such biological material to the FAA was required, under NASA planetary protection guidance, as part of the launch licensing process. In light of this incident, the PPIRB recommended that “[b]reaches of PP reporting or other requirements should be handled via sanctions that hold the root perpetrator accountable, rather than increasing the verification and regulatory burden on all actors.”29 This recommendation raises a number of questions, including the following:

- What legal “requirements” for planetary protection did the payload owner allegedly breach? and

- What legal “sanctions” could the federal government apply to the payload owner for violating such requirements?

The committee takes no position on how the federal government can address the lack of clarity and uncertainties concerning the application of federal law and regulations to the planetary protection aspects of private-sector missions, especially those implemented without NASA participation. The 2018 report recommended congressional action to authorize a federal agency to authorize and continually supervise the space activities of nongovernmental entities for planetary protection purposes.30 Similarly, the PPIRB report recommended that “NASA should work with the Administration, the Congress, and private sector space stakeholders to identify the appropriate U.S. Government agency to implement a [planetary protection] regulatory framework.”31 The federal agency with authority could oversee a legal framework that combines binding regulations, nonbinding guidance, and oversight processes in order to achieve planetary protection and the transparency and predictability private-sector actors need. In responses to questions from the committee, the National Space Council noted, for example, that planetary protection objectives can be met through “voluntary, non-binding measures” and “methods such as independent reviews or levying disclosure requirements.”32

Finding: Problems persist with whether and how U.S. federal law regulates private-sector space activities for planetary protection purposes concerning launch, on-orbit, and re-entry activities. These problems create challenges for U.S. compliance with the OST’s obligations concerning the authorization and continual supervision of activities of nongovernmental entities and also undermine the private sector’s need for a transparent and efficient legal and regulatory framework to support expanding of private sector exploration and uses of space.

Recommendation: NASA should work with other agencies of the U.S. government, especially the Federal Aviation Administration, to produce a legal and regulatory guide for private-sector actors

___________________

27 See NASEM, 2018, p. 86.

28 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Finding [30].

29 See PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Recommendation [31].

30 See NASEM, 2018, Recommendation 6.2.

31 PPIRB, 2019, Supporting Recommendation [58].

32 Response from National Space Council to questions posed by the committee received from Ryan Whitley, director of Civil Space Policy, National Space Council on January 6, 2020.

planning space activities that implicate planetary protection but that do not involve NASA participation. The guide should clearly identify where legal authority for making decisions about planetary protection issues resides, how the United States translates its obligations under the Outer Space Treaty into planetary protection requirements for nongovernmental missions, what legal rules apply to private-sector actors planning missions with planetary protection issues, and what authoritative sources of information are available to private-sector actors that want more guidance on legal and regulatory questions.

Building the Scientific and Technological Foundation for Planetary Protection Policy on Human Missions to Mars

The PPIRB and 2018 reports took note of planned, proposed, and potential human missions to Mars and for which existing planetary protection policy does not provide adequate guidance. The committee agrees. The reports also contained recommendations designed to help NASA develop planetary protection policy for human missions to Mars. The committee supports those recommendations.

In both the PPIRB and 2018 reports, one of the key themes involves developing innovative guidelines that apply to the new types of missions. The 2018 report concludes that “NASA’s process for developing a human Mars exploration policy should include examination of alternative planetary protection scenarios.”33 In addition, the latter report also noted that “rather than thinking about forward contamination in terms of an entire body, assessing the effects of human presence on local and regional scales might be more effective.”34 Similarly, the PPIRB report made the following recommendation:35

NASA should consider establishing [zones] … considered to be of high scientific priority for identifying extinct or extant life, and [zones] where the larger amounts of biological contamination inevitably associated with human exploration missions, as compared to robotic scientific missions, will be acceptable.

Both reports went on to call for research to enable mission planners to define exploration zones on Mars. There are important questions about atmospheric transport of dust and gases, the likely range of biological materials released from a hypothetical accident at an occupied site, the survivability of terrestrial microbes on Mars, and the applicability of modern genomic techniques for measuring and monitoring contamination. Both reports also urged NASA to invest in research and technology pertaining to methods to detect life and its components, noting that using the latest information and approaches in life detection, contaminant reduction, and characterization of contaminants will ensure that the planetary protection requirements levied on future missions are sufficiently streamlined and effective.

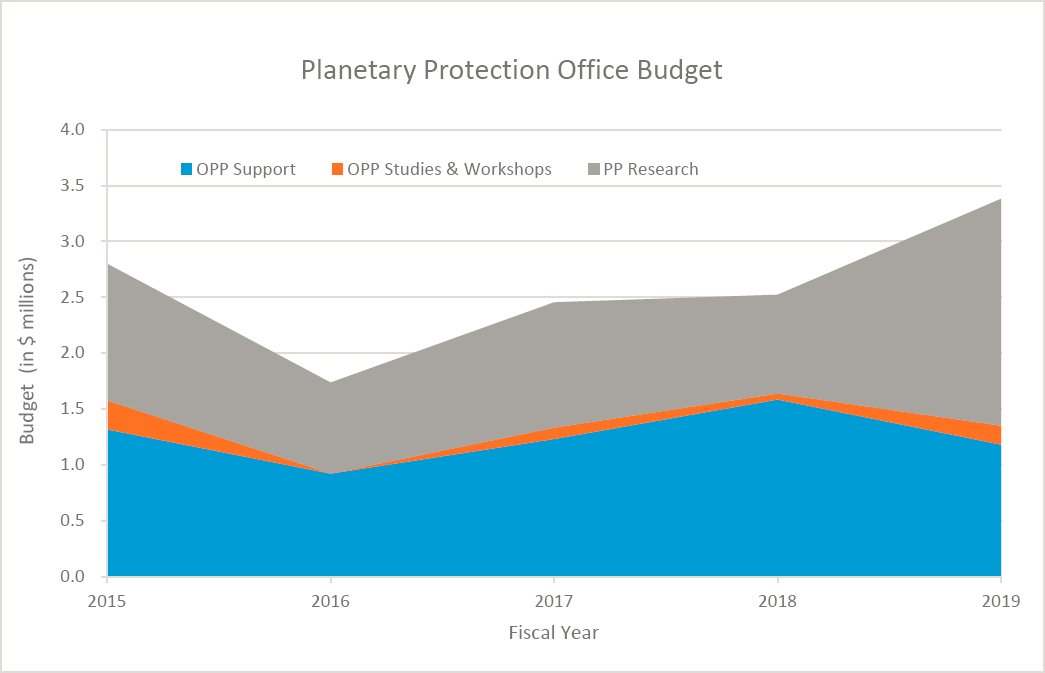

The necessary research program requires bringing the appropriate resources to the problem. However, the low level of funding for NASA OPP over the period 2005-2019 has only been able to support an average two to three research grants per year.36 However, in the last couple of years, this number has more than doubled (see Figure 3.1). In describing its recommendation for new research, the PPIRB report says, “This likely requires additional PPO funding to be effective.”37 Similarly, the 2018 report contained the following finding:38

NASA has not adequately funded the research necessary to advance approaches to implementing planetary protection protocols and verifying that those protocols satisfy NASA’s increasingly complex planetary protection requirements.

___________________

33 See NASEM, 2018, p. 84.

34 See NASEM, 2018, pp. 79-80.

35 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Recommendation [38].

36 The number of proposals selected for funding by the Planetary Protection Research program offered annually via NASA’s Research Opportunity in Space and Earth Science (ROSES) program between 2005 and 2018 is as follows: 2005 (1), 2006 (4), 2007 (6), 2008 (2), 2009 (0), 2010 (1), 2011 (5), 2012 (1), 2013 (not offered), 2014 (7), 2015 (0), 2016 (not offered), 2017 (5), 2018 (7), and 2019 (not offered). Details available at https://nspires.nasaprs.com/external.

37 See PPIRB, 2019, Major Recommendation [5].

38 See NASEM, 2018, p. 65.

For an agency program of solar system exploration and planning for human exploration missions, costing several billion dollars per year, an investment in relevant planetary protection research and technology of less than one tenth of one percent of that total seems inadequate.

Finding: Although NASA recognizes that existing planetary protection policy is inappropriate for human missions to Mars, it has not developed a strategy for producing practical planetary protection measures for such human missions. The lack of a strategy stems, in large measure, from the fact that NASA has not conducted the research and development needed to build the scientific and technological foundation for planetary protection measures designed specifically for human missions to Mars.

Recommendation: NASA should make the development and execution of a strategy to guide the adoption of planetary protection policy for human missions to Mars a priority.

The committee has chosen to emphasize the need for a strategy for humans to Mars because of the magnitude of the task and because this topic is emphasized in both the PPIRB and 2018 reports. However, it could be argued that the same kind of effort will be needed to address topics not discussed in the 2018 report and, thus, technically beyond the scope of the current study. Such topics include, for example, relaxing the planetary protection requirements for large areas of the Moon and thus opening them up to private-sector missions and addressing other planetary protection issues associated with the future exploration of the ocean worlds and other astrobiologically significant environments

Essential elements of such a Mars-focused strategy could include the following:

- A process to identify the most promising concepts for achieving planetary protection objectives in the context of human missions, such as high-priority astrobiological zones and human exploration zones building on the work done to date by COSPAR, NASA, and the European Space Agency;39

- Establishment of an adequately funded program of research and development to answer questions and address challenges raised by the most promising concepts for integrating planetary protection in human missions, such as the potential for transport of material and the survivability of terrestrial microorganisms on Mars; and

- A plan to develop planetary protection policy for human missions to Mars on a timeline that permits the integration of such research into mission planning and implementation at the earliest possible stages.

Action on the recommendations above will enable the development of science-based guidelines to be implemented on both government-led and private-sector-led missions. Developing these guidelines in a timely manner would promote an earlier understanding of requirements and would reduce costly system redesign.

EXPEDITING THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEW APPROACHS TO PLANETARY PROTECTION

The committee recognizes that NASA needs time to implement fully the recommendations offered by the PPRIB and 2018 reports, as well as those the committee makes. For example, marshaling the human spaceflight and science communities to conduct the necessary research to further define exploration zones and mission recategorization will not be a trivial exercise. However, NASA can make some rapid progress on important aspects of a new approach to planetary protection policy identified by the PPIRB report, the 2018 report, and this committee. The committee believes that NASA can use the growing importance of small satellites to begin to build its new approach to planetary protection.

The PPIRB report drew attention to the planetary protection challenges that small, low-cost spacecraft missions present to NASA, private-sector space enterprises, and university researchers. The committee agrees with PPIRB’s emphasis on this issue. In so doing, the committee takes note of important developments in this area, including the following:40

- NASA’s delivery of two small, low-cost communication-relay satellites (MarCO-6U) for Mars missions aboard the 2018 Insight mission;

- The use of SmallSats as part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program designed to send small robotic landers and rovers to the Moon;

- The missions selected as part of NASA’s Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx) program. The Lunar Polar Hydrogen Mapper was selected via the first SIMPLEx solicitation. The second SIMPLEx solicitation resulted in the selection of three more missions: Lunar Trailblazer, Janus, and the Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers; and

- The submission of 18 SmallSat concepts (all orbiters) by participants in the Mars science community in response a call for mission concepts by the NASA-chartered Mars Architecture Strategic Working Group.

___________________

39 See, for example, M.S. Race, J.E. Johnson, J.A. Spry, B. Siegel, and C.A. Conley (eds.), Planetary Protection Knowledge Gaps for Human Extraterrestrial Missions—Final Report, DAA_TN36403, NASA Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate and NASA Planetary Protection Office, Washington, D.C., 2015; G. Kminek, B.C. Clark, C.A. Conley, M.A. Jones, M. Patel, M.S. Race, M.A. Rucker, O. Santolik, B. Siegel, and J.A. Spry (eds.), Report of the COSPAR Workshop on Refining Planetary Protection Requirements for Human Missions, NASA Science Mission Directorate and Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C., 2016; and M.S. Race, J.A. Spry, B. Siegel, C.A. Conley, and G. Kminek (eds.), Final Report of the Second COSPAR Workshop on Refining Planetary Protection Requirements for Human Missions and COSPAR Work Meeting on Developing Payload Requirements Addressing PP Gaps on Natural Transport of Contamination on Mars, COSPAR, Paris, France, 2019. All three documents are available at https://sma.nasa.gov/sma-disciplines/planetary-protection.

40 For more information about the NASA’s small spacecraft programs see, for example, https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/smallsats.

Each of these executed or proposed missions or payloads requires or needs planetary protection attention at the mission development stage and as mission implementation proceeds. The PPIRB report expressed concern that meeting planetary protection objectives might place undue burdens on small, low-cost spacecraft, perhaps limiting their use of for entrepreneurial and scientific research purposes. The potential burden arises because limited budget resources and time require the developers of small spacecraft to adopt a more refined balance between risk and cost than is typically the case for large spacecraft. The chair of the PPIRB told the committee that the PPIRB discussed whether complying with planetary protection measures might produce a base or minimum cost that could be beyond the means of the developers without deep pockets. Similarly, NASA’s Planetary Protection Officer, Lisa Pratt, informed that committee that, among other things, completing trajectory calculations required for planetary protection purposes might stress the economic resources of entrepreneurs and university researchers interested in SmallSat capabilities.41 The committee also learned that the OPP has taken steps to simplify some potentially costly requirements by developing “a single-page organic inventory template to reduce the workload for the CubeSat teams and to standardize the input into the aggregation activity.”42

Finding: NASA has an opportunity to be proactive in addressing the planetary protection challenges generated by small, low-cost missions and thereby contribute to the potential that small, low-cost spacecraft offer for scientific, academic, and private-sector exploration and use of space.

The committee believes that effectively addressing the planetary protection challenges presented by small spacecraft missions could allow NASA to begin building its new approach to planetary protection policy. An expedited focus on low-cost missions would let NASA start addressing the three strategic areas for action in planetary protection policy that this committee draws from the recommendations of PPIRB and 2018 reports. An effort targeted on small, low-cost spacecraft would also signal that NASA understands the changing environment for planetary protection and is ready, willing, and able to bring planetary protection policy effectively and efficiently into this new age of space activities.

NASA has the expertise to convene experts to clarify these areas, and the effort can be carried out in a relatively short time at a modest cost. By conducting these actions, the agency can take near-term steps to ameliorate an emerging concern identified by the PPIRB report and with which this committee agrees. The effort can also provide an opportunity for NASA to demonstrate success in addressing the committee’s highest priority issues—stakeholder engagement, research to facilitate new planetary protection approaches, and legal and regulatory clarity.

___________________

41 Briefing to the committee by Lisa Pratt on November 22, 2019.

42 Private communication from J. Andy Spry to G. Scott Hubbard, January 22, 2020.