The opening session provided a foundation for the rest of the workshop by introducing the role of cities in planetary health and the determinants of urban health and health inequities. The three speakers in this session were Sir Andy Haines, professor of environmental change and public health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Health; David Vlahov, associate dean for research and professor at the Yale University School of Nursing and professor of epidemiology at the Yale University School of Public Health; and Ana Diez-Roux, dean and distinguished university professor of epidemiology at the Drexel University Dornsife School of Public Health and director of the Drexel University Urban Health Collaborative. After the three presentations, Jo Ivey Boufford moderated an open discussion with workshop participants.

THE ROLE OF CITIES IN PLANETARY HEALTH

Sir Andy Haines (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Health) began his presentation by quoting from The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission report (Whitmee et al., 2015) and from Pope Francis to call

for a more expansive conversation. This conversation would include a wide range of stakeholders to address human-driven environmental challenges that affect the entire planet and that potentially threaten to undermine recent progress in global health. He noted the term Anthropocene epoch was coined to capture the idea that environmental changes driven by humans have been so dramatic that they reflect the start of a new geological period on Earth (Steffen et al., 2007; Whitmee et al., 2015; Zalasiewicz et al., 2010).

Another term used in this context, explained Haines, is the Great Acceleration, which refers to rapid advances in human health, economic output, and life expectancy, as well as to accompanying declines in infant, child, and maternal mortality, that have occurred since the middle of the twentieth century. It also refers to the accelerating exploitation of the planet’s resources, including fertile land, fresh water, and fisheries, and to the concomitant negative impact on the planet’s environment. To further frame the discussion, Haines mentioned planetary boundaries, a concept that outlines nine planetary boundaries related to climate change, ocean acidification, stratospheric ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, biogeochemical flows that interfere with phosphorus and nitrogen cycles, global freshwater use, land-system change, rate of biodiversity loss, and “novel entities” (a term that largely refers to chemical pollution) (Rockström et al., 2009a,b; Steffen et al., 2015). According to Haines, crossing any of these boundaries raises the prospect of deleterious or even catastrophic effects on the planet’s environment and, by implication, on human health, particularly when multiple boundaries are crossed. Notably, Haines noted that three boundaries have already been crossed—phosphorus loading, nitrogen loading, and genetic diversity. Abrupt, nonlinear changes can occur in natural systems when they are subject to rapid and extensive change, and such changes may be self-reinforcing.

According to Haines, with increasing urbanization of the human population, the future of planetary health and the interaction between environmental change and human health will depend substantially on policies enacted in cities. Haines explained that “cities are the engines of economic activity, responsible for the bulk of global economic activity and about three-quarters of the global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.” Transportation is one major source of urban emissions, and a strong relationship exists between urban density and transport-related emissions. Haines noted that Atlanta and Barcelona metropolitan areas, for example, both house roughly 5 million people, but Atlanta emits about 10 times more transport-related greenhouse gases than Barcelona does. In large part, this difference arises because Atlanta’s metropolitan area covers approximately 4,300 square kilometers while metropolitan Barcelona covers a mere 160 square kilometers. As a result, people from Atlanta spend more

time driving and less time walking, cycling, or using public transport than do residents of Barcelona. They also depend more on private cars.

Haines noted the importance of considering the inverse relationship between urban density and transportation-related emissions when building (e.g., in Africa) or expanding (e.g., in India) new cities to prevent them from becoming carbon-dense locations. For existing cities, Haines said, the challenge is to decarbonize and retrofit them to address realities of the Anthropocene epoch.

Although climate change has begun to affect human health and is likely to have an increasingly negative effect over time, air pollutants such as fine particulate matter and ozone have already had major adverse effects on human health. Indeed, air pollution is one of the most important environmental risk factors for morbidity and mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that ambient air pollution kills about 4 million people per year (Gurny and Prüss-Üstün, 2016), but recent estimates suggest the death toll from ambient air pollution could be as high as 9 million per year (Lelieveld et al., 2019b). Haines said climate change can affect health through direct mechanisms, such as increasing exposure to high temperatures and to extreme events (e.g., hurricanes and floods), as well as through indirect mechanisms, such as vector-borne diseases (e.g., dengue and zika), increased exposure to allergens, and undernutrition caused by reduced agricultural productivity. The World Bank has estimated that, in the absence of effective action, climate change could push 100 million people back into poverty by 2030 (Hallegatte et al., 2016) and will likely lead to increased mortality (Preston, 1975).

Haines said that air pollution and climate change can be considered two sides of the same coin; most air pollutants affect the climate directly or indirectly, and most greenhouse gas sources co-emit air pollutants or contribute to their formation. This connection offers a two-for-one opportunity because decarbonizing the economy reduces air pollution. Haines said a general relationship exists between development and greenhouse gas emissions; however, there is no absolute reason why a city could not transition from a low- or middle-income status to a higher-income status along a low air pollution, low greenhouse gas trajectory.

By their very nature, cities are hotter than surrounding rural areas—a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect (Media in Africa, 2011). The heat island effect can be reduced by planting trees and by having open water and green spaces, but climate trajectories may have the most significant effect on urban heat-loading. For example, a study in 2017 on the challenge of urban heat exposure under climate change projected a much lower urban temperature-loading by the second half of the twenty-first century through a low-emission trajectory than what would

occur through a high-emission trajectory (Milner et al., 2017). This study projected that cities such as Madrid could see temperature increases as high as 7°C by the end of the century. Haines noted that the frequency of heavy precipitation events and extremely intense storms will likely increase with climate change and will likely pose a threat of urban flooding. At the same time, he added, droughts and water shortages will likely become more common.

Given the likelihood that the planet’s temperature will continue to rise, Haines said the question becomes one of how to develop sustainable, healthy cities that are resilient in changing climates, reduce emissions to prevent the worst effects of climate change, and protect the health of residents. Regarding resiliency and climate change adaptation, one approach increasingly implemented is establishing early-heat warning systems that identify temperature thresholds over which harm to human health increases dramatically. These heat early warning systems forecast the likelihood of crossing those thresholds, issue high-heat warnings based on risk assessments, and implement interventions to keep people cooler and more hydrated in their homes. He noted that a growing number of cities, including those in lower- and middle-income settings such as Ahmedabad, India, have implemented such systems. After they went live, death rates associated with extreme heat waves dropped (Hess et al., 2018).

Implementing flood protection that uses nature-based solutions, such as restoring wetlands and coastal mangrove ecosystems, poses another possible adaptation. In addition, protecting and restoring watersheds potentially increases supplies of fresh water. Such systems will need to be designed carefully because wetlands, for example, can also host populations of disease-carrying mosquitoes. Haines noted that “we need to think about minimizing the adverse effects on health when designing and implementing these nature-based solutions.”

Decarbonizing the energy supply system can dramatically benefit health, he noted (Haines et al., 2009). One study, for example, showed that decarbonizing the world’s economy—removing all sources of fossil fuel and transitioning to clean renewables—could prevent 3.5 million premature deaths per year by reducing ambient air pollution (Lelieveld et al., 2019a). Removing all human-related sources of ambient air pollution, including those from households and agriculture, would likely prevent another 2 million premature deaths, Haines added. He also noted that cities and their residents would realize significant health benefits by expanding sustainable mobility options such as public transport systems and car-free zones; increasing walkability, car-sharing, and bike-sharing schemes; and creating low-emission zones.

A range of different innovations in sustainable mobility could reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and increase physical activity among city residents. In fact, when Haines and his collaborators modeled the effects of increased walking and cycling and of reduced driving on the health of London residents, the residents showed significant improvement in health and reduction in health care costs—even after Haines and his collaborators accounted for a small projected rise in injuries that pedestrians and cyclists might experience from encounters with motorized vehicles (Jarrett et al., 2012; Woodcock et al., 2009). Studies in the United Kingdom and Canada have also found that urban residents who mostly walk or cycle have the lowest percentages of body fat and have a lower likelihood of diabetes (Creatore et al., 2016; Flint and Cummins, 2016). Though some may be concerned that exposure to air pollution could negate the benefits of cycling and walking, a 2016 study projected that cycling or engaging in other forms of outdoor exercise for as many as 300 minutes per day is beneficial even at particulate matter levels of 50 micrograms per cubic centimeter of air—which is considered heavily polluted (Tainio et al., 2016). Haines said, “In practice, for most cities, cycling and walking is a good solution, and, of course, you get more people out of their cars and that will reduce pollution.” The key to realizing these benefits, he added, is to make cities more walkable and bike-friendly. Toward that end, he noted, mobile phone applications can direct people to walking and biking routes that are more pleasurable and that avoid the most polluted streets.

In addition, increasing green spaces can help reduce pollution levels and benefit human physical and mental health. One large study from Canada, for example, found that proximity to urban green spaces reduced mortality from cardiovascular and respiratory disease (Crouse et al., 2017). However, Haines noted that cities that seek to add green spaces need to make them readily accessible to all residents and not just those who are wealthy.

Improving the energy efficiency of a city’s housing stock is another route to reducing a city’s carbon footprint. However, a caveat exists: Sealing houses to increase their energy efficiency would also increase indoor pollutant levels unless homes were equipped with energy-efficient ventilation and with heat recovery. Haines said that adequately retrofitting urban-housing stock would eliminate millions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions and would reduce premature deaths (Wilkinson et al., 2009). Improving housing stock and reducing indoor air pollution would also benefit urban residents in low-income settings (Haines et al., 2013).

Food production and consumption are major drivers of environmental degradation and account for approximately 30 percent of the

planet’s greenhouse gas emissions. One way to improve in this realm, said Haines, is to reduce the amount of food produced but not consumed, which currently accounts for about 30 percent of agricultural production (Macdiarmid et al., 2016). A systematic review has shown that promoting healthy, more environmentally sustainable diets—those with increased consumption of fruit and vegetables and decreased consumption of animal products, particularly ruminant meat—would reduce the use of land and water and cut greenhouse gas emissions by 20–30 percent medians for these indicators across all studies (Aleksandrowicz et al., 2016). He noted that some cities are experimenting with urban farming, aquaponics, and other alternative and localized food production systems (Säumel et al., 2019). Haines said, “Whether they will make a large-scale impact on the environmental footprint of the system we do not know yet, but there is certainly a lot of interest in those kinds of innovations at the city level combining sustainable nutrition, low environmental impacts, and job creation.” In fact, many cities are becoming more ambitious about tackling their energy consumption and environmental footprints on a variety of fronts.

In closing, Haines reminded workshop participants that only a few decades are left to reduce the risks of dangerous climate change by keeping global average temperature increases to 2 degrees or less above preindustrial measurements. One estimate suggests that, at current rates of emissions, the 2-degree target would be reached after 35 to 41 years (Goodwin et al., 2018). Of great concern is the fact that greenhouse gas emissions reached a record level in 2018 and are still rising (UNEP, 2019). Haines said, “That implies we need to cut emissions very urgently, indeed. We have to keep the pressure up to work toward rapid decarbonization as soon as possible, and, in doing so, the policies enacted in cities will be absolutely crucial toward driving us to a sustainable economy in the Anthropocene epoch.”

DETERMINANTS OF URBAN HEALTH AND HEALTH INEQUITIES

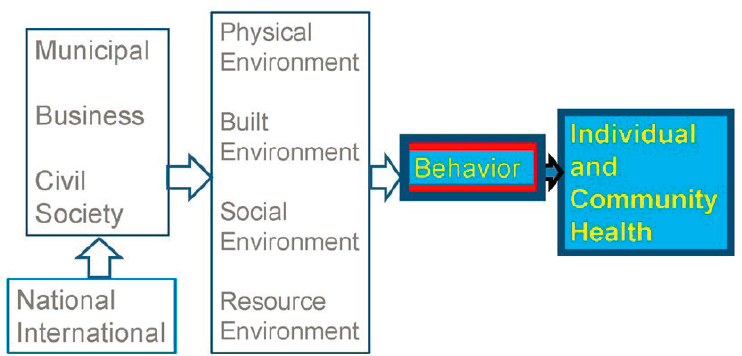

David Vlahov (Yale School of Nursing) presented a conceptual framework for urban determinants of health that examines various components of urban life—such as physical, built, social, and resource environments—that influence people’s behavior and that, in turn, affect individual and community health (see Figure 2-1). The physical environment, which Haines addressed, includes climate, air, water, noise, and nature. In contrast, the built environment considers land tenure, housing, transportation, water sanitation, and drainage. The social environment includes social networks, social supports, social capital, social isolation, violence,

SOURCE: As presented by David Vlahov, June 13, 2019.

and extreme poverty—all components of how people engage and interact with one another. Finally, the resource environment comprises health services, social services, food availability and access, education, and work. Each of these aspects of the urban environment is influenced by municipal government, business, and civil society, which are, in turn, affected by various national and international influences.

Vlahov said four aspects—size, density, diversity, and complexity—characterize cities, and cities are neither good nor bad. Because of their size, density, and diversity, cities afford opportunities to reach large numbers of people and likely include residents with specialized talents who can play various roles in disseminating information. He added that complexity can be a positive virtue; it can provide an opportunity for inter-sectoral interactions. Cities also have negative aspects such as overcrowding; dispersal or urban sprawl; and social exclusion and culture clashes, which can accompany diversity. In addition, reaching every resident can be challenging in cities that are large. Sectoral divisions that can occur within interlocking systems also represent a potential downside of complexity.

In 1976, the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements held in Vancouver, Canada, declared that adequate shelter and services are basic human rights recognized in international law as part of the right to an adequate standard of living. The conference also declared that governments should help local authorities participate more in national development and that land use and tenure should be subject to public control. The involvement of public–private partnerships (PPPs) in land tenure and

housing creates opportunities for the private sector to contribute capital up front and to deliver products efficiently. In contrast, the public sector controls the regulating environment and, when it has resources (e.g., land), implements projects.

Vlahov noted, however, that there are a number of preconditions that need to be met in order to sufficiently mitigate risks before a PPP that appeals to the private sector may be established. These preconditions may include changes in specific laws that are accompanied by analysis of the partnership’s feasibility; social and environmental studies that support the partnership’s formation; and willingness to pay the partnership’s assessments. In short, the private sector needs to believe that it can make a positive return on its investment in a project. Toward that end, the public sector engages in risk-mitigation measures (e.g., developing strong legal frameworks) to engender more favorable investment conditions.

Urban transportation, discussed later in the workshop, is one model of a PPP. The public sector, Vlahov explained, conducts analyses to ensure feasibility, and the private-sector investor or concessionaire implements the project according to a negotiated structure, such as a building-operate-transfer or building-own-operate arrangement. Typically, such projects are implemented through straightforward deals between individual landowners and the government agency in charge of the project as well as between the agency and the investor or concessionaire. Transportation projects, he added, can benefit from including a separate entity that deals with residents who may be displaced by the projects.

Projects formed to address slum conditions require a more complicated PPP structure because of their potential to displace residents of the area slated for redevelopment. Vlahov noted that early housing projects resembled other infrastructure projects by excluding input from or coordination with affected communities; while those projects may have improved slums, they did not necessarily improve the livelihoods of people who lived in slums. One lesson learned from these early projects was that urban renewal requires both physical infrastructure improvements and opportunities for residents to become integrated citizens of society. In other words, developing economic opportunities for residents may be an advisable complement to physically redeveloping neighborhoods.

Vlahov went on to explain that network partnerships represent another model that extends PPPs by adding a nongovernmental organization (NGO) or a community benefit organization (CBO) to the mix and tasking it with introducing more socially oriented goals, such as facilitating steps to integrate the redeveloped area into its larger community. These three-way partnerships between various actors involve interdependent, adaptable relationships that are based on trust and that, sometimes, may even exist in lieu of contracts. In some instances, private

participation may stem from enlightened self-interest, such as when a project is located in the same city as the private entity’s headquarters.

The big question, Vlahov said, is how to incentivize members of the private sector to take on redevelopment projects that would otherwise be unprofitable for them. One answer he suggested is for government to make land available at below-market costs. A second possibility is to redevelop land with what is known as an incentivized floor space index—an allowance to engage in higher-density development. Another important question concerns what is required of developers, which can include clearing land, providing temporary shelter and transportation to current residents, and rehousing eligible residents. For example, a slum improvement project in Ahmedabad, India, required developers to rehouse slum dwellers in multistory tenements at no cost to the dwellers—if they could prove they had lived in the slum at a specified cut-off date (Mahadevia et al., 2014).

Developers were required to complete the Ahmedabad project on a 3-year deadline, and completion included obtaining multiple levels of government clearance and convincing residents to consent to the redevelopment. Obtaining this consent proved difficult; many residents thought the free housing was too good to be true and considered it a mere ploy to evict them from the slum. Though they were not required to do so, the developers recruited several NGOs and CBOs to act as intermediaries, negotiate with the residents, and hold the developers responsible for fulfilling their promises.

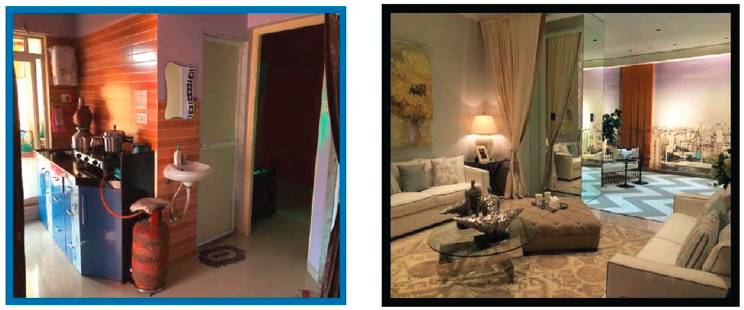

Vlahov noted several limitations to the Ahmedabad project. First, multiple developers were allowed to work in a particular slum, and this unregulated competition confused residents. Second, no specific quality standards were set for the rehabilitated buildings, which raised concerns about resulting buildings becoming vertical slums. Third, no clear plan existed for slum dwellers who did not meet the eligibility cut-off date or for the 25–30 percent of residents who did not agree to go along with the project. Additionally, while this model provides free housing to slum dwellers, it also allows developers to load the cost of rehabilitation onto salable units in the development. As a result, developers can sometimes be reluctant to construct salable units that are sold as anything but luxury homes (see Figure 2-2). Ultimately, that dynamic leads to increased housing prices and excludes the middle class from homeownership.

As cities grow and expand over the next 50 years, PPPs can contribute innovations that include sustainable technologies. The conventional economy of take-make-waste and construction waste generates about 535 million tons of debris each year as well as 60 million tons of food waste. Vlahov said the challenge is to move from a conventional economy to a circular one that recycles as much as possible, throws away as little

SOURCES: As presented by David Vlahov, June 13, 2019; Zhang, 2016.

as possible, and, in the end, uses as few resources as possible. Applying circular economic thinking, he said, could mean less produce in landfills if produce is instead used to make building materials. One company, for example, is using mycelium to convert agricultural waste into a matrix of white fibers that can be turned into a solid material. Another company, in order to create bricks from sand without using clay or heat, is harnessing the natural process coral uses to construct reefs.

Vlahov also noted that a number of NGOs have worked with individual communities and with the private sector to incrementally upgrade informal settlements and slums and to build local enterprise capacity and resilience within the community. The iShack Project in South Africa, for example, is using solar electricity to demonstrate how green technologies can jump-start redevelopment of informal settlements and slums.

Concluding his comments, Vlahov said private markets clearly cannot efficiently provide universal housing for the growing number of people who live in slums around the world. Moreover, governments are often hostile to poorer populations, and collective, grassroots action becomes the only way to provide adequate housing for all (McGuirk, 2015).

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES FOR PROMOTING URBAN HEALTH

Ana Diez-Roux (Drexel University) opened her presentation with six reasons for paying attention to urban health. These reasons included that the future of humanity rests largely in cities; the health implications of city living are variable and malleable; the health consequences of city

living are not the same for everyone; health in cities is driven by factors at multiple levels; little is known about the effects of urban policies on health or health equity; and urban health and environmental sustainability are linked and reinforcing.

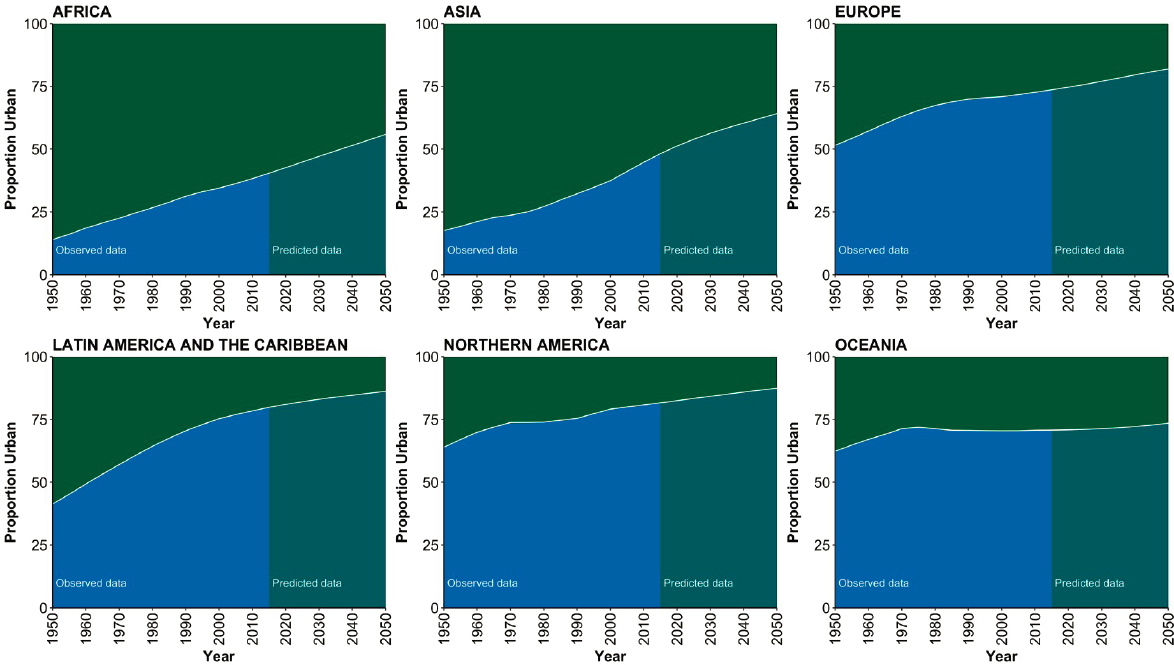

Echoing the previous speakers, her first reason was that the future of humanity rests largely in cities—a consequence of increasing urbanization among the human population (see Figure 2-3). She noted that more than half of the cities in lower- and middle-income countries have fewer than 500,000 residents and pose opportunities for design; these smaller cities could be made healthier and more environmentally sustainable before they become too large to tackle. Diez-Roux said, “Certainly, there is work to be done in big cities, but there is this incredible opportunity in emerging cities all over the world.”

The second reason to focus on urban health is that the health implications of city living are variable and malleable. The correlates of city living, Diez-Roux said, are that cities have higher population density; greater diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, national origin, and social class; greater concentration of economic activity; and higher levels of innovation and creativity compared to rural areas. In addition, social interactions in cities are more intense and differ qualitatively from those in rural areas. What this means for health, she said, includes both positives and negatives (see Table 2-1), and the balance is highly context-dependent.

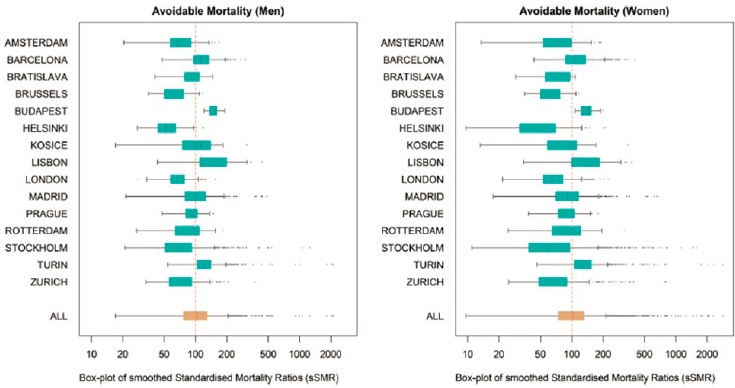

For example, in the United States, the incidence of obesity in both men and women is lower in urban areas (Meit et al., 2014), whereas in most other countries, the incidence of obesity is higher in urban areas (Prasad et al., 2016). Similarly, Diez-Roux noted, data from 15 European cities show an incredible heterogeneity in avoidable mortality across not only cities but also urban neighborhoods (Hoffmann et al., 2014) (see Figure 2-4), but data from the United States show significant variability regarding homicide rates and life expectancy across cities (Chetty et al., 2016). Diez-Roux said, “This is very important because it means there are things that we can do to change the relationship between urban living and health.” It also means that potential lessons in this heterogeneity may inform urban design, governance, and management in order to reduce health inequities, she added.

This heterogeneity leads to a third reason to care about urban health: The health consequences of city living are not the same for everyone. Diez-Roux said, “It is important to remember that cities are characterized by large social and health inequalities.” In the United States and internationally, for example, income inequality in large cities exceeds that of rural areas, and income inequality is linked to health inequalities and to differences in life expectancy. She explained that these inequalities are partly driven by residential segregation and by resulting differences in resource

SOURCES: As presented by Ana Diez-Roux, June 13, 2019. From 2014 revision of the World Urbanization Prospects, by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. © 2015 United Nations. Reprinted with the permission of the United Nations.

TABLE 2-1 Possible Health Consequences of City Living

| Minuses | Pluses |

|---|---|

| Adverse environmental exposures concentrated and magnified—air pollution, industrial exposures, poor housing, heat/climate change | Income and work benefits |

| Physical environment effects on behaviors—urban design and sedentarism, processed foods | Potential for better access to services as a result of proximity and greater availability |

| Limited access to services (overcrowding, housing, water and sanitation, health, social) | Positive social interactions, cohesion, support, and advocacy |

| Social stressors, conflict, violence, discrimination | Creativity, social interaction as health enhancing |

| Urban policies can promote health |

SOURCE: As presented by Ana Diez-Roux, June 13, 2019.

NOTES: The box plots show the range of mortality between areas with the lowest and highest mortality. Rectangles denote the range between the 25th and 75th percentiles, and individual dots represent single areas considered outliers with very high mortality.

SOURCES: As presented by Ana Diez-Roux, June 13, 2019; Hoffmann et al., 2014.

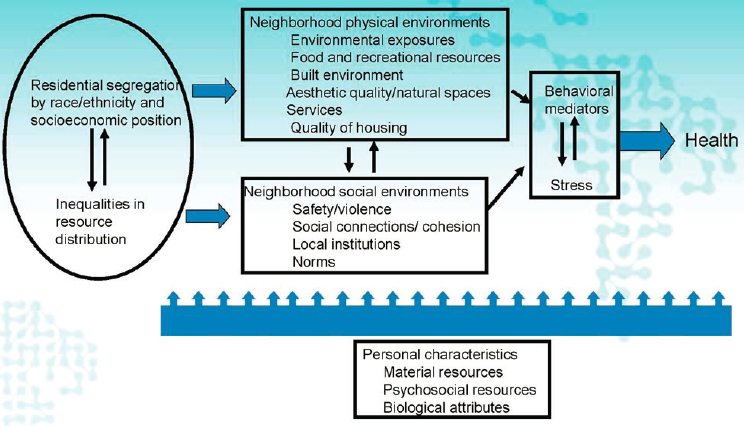

distribution across neighborhoods, which, in turn, create differences in physical and built environments, food and recreational resources, services, natural spaces, environmental exposures, and aesthetic and housing quality. Social environments also change and may lead to differences in safety, violence, social connections, and institutional locations. Taken together, these differences reinforce each other and lead to behavioral and stress-related outcomes that also interact to affect health (see Figure 2-5).

The fourth reason urban health matters is that factors at multiple levels drive health in cities and create opportunities for multilevel interventions both inside and outside of the health sector. Diez-Roux noted that economic policies, social inclusion, mobility, food policy, urban development, and other drivers shape local and proximal determinants of health, and each driver offers opportunities for multi-sector interventions.

Diez-Roux also discussed a fifth reason to be concerned about urban health: Cities are already enacting policies, but little is known about the effects of urban policies on health or health equity. Opportunity exists, then, to generate evidence of the health and environmental impacts created by policies that cities are currently implementing. For example, one evaluation examining the effect of a new cable-car system on violence in Medellin, Colombia, found lower levels of violence in neighborhoods served by that transit system (Cerda et al., 2012).

SOURCES: As presented by Ana Diez-Roux, June 13, 2019; Diez-Roux and Mair, 2010.

Her sixth reason, one that Haines also articulated, is that urban health and environmental sustainability are linked and reinforce each other. Diez-Roux said, “This is about improving urban health and improving environmental sustainability, and the good thing is we can do both at the same time.” In her opinion, two options exist for urban development and design. The first features more sprawl, more energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, higher levels of air pollution, more dependence on automobiles, increased consumption of processed foods and meat, less physical activity, and increased social consequences such as isolation, violence, and mental health concerns. The alternative option features compact, energy-efficient development with active public transportation, sustainable food, reduced air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, more physical activity, increased consumption of fruits and vegetables compared to meat, and reduced impact on biodiversity, biomass, and croplands due to a smaller urban footprint. In addition, the latter model would more likely promote inclusion and equity.

Diez-Roux noted that major drivers of differences in health across and within cities remain largely unexplored. She said cities are acting, including actions designed to benefit both health and environment, but they are not rigorously evaluating their actions. She added that opportunities for big data, machine learning/artificial intelligence, multiple methods, and systems approaches to compare and share results across cities are largely untapped, and the Global South provides an unexplored resource for understanding how best to manage, govern, and develop cities so they are healthy and environmentally stable.

As an example of the type of work she would like to see conducted, Diez-Roux described the Salud Urbana en America Latina/Urban Health in Latin America (SALURBAL) Project. In the project, she and 14 international partners, primarily in Latin America, collaborated to create the evidence base needed to make Latin American cities, as well as others, healthier, more equitable, and more environmentally stable. This 5-year project, which is funded through March 2022, aims to engage policy makers and the public in new dialogue about urban health and sustainability and about implications for societal action. It also aims to create a platform and a network that will ensure continued learning and subsequent translation of lessons into actions. She said, “We have to change the mindset of how we think about this, and that involves thinking about health as more than health care and also thinking about health and the environment being linked to one another.”

Latin America serves as the test site for this project because it is highly urbanized—roughly 80 percent of the 505 million people in the region live in cities—and has diverse urban landscapes and high levels of social

inequality. According to Diez-Roux, the project’s four goals include the following:

- Identify city and neighborhood drivers of health and health inequalities among and within cities.

- Evaluate the health, environmental, and equity impacts of policies and interventions.

- Employ systems thinking, simulation models, and participatory group model building to evaluate urban–health–environment links and plausible policy impacts.

- Disseminate results and engage policy makers to promote new ways of thinking about the drivers of urban health and the types of policies and interventions that could improve health and sustainability in cities (Diez-Roux et al., 2018).

So far, Diez-Roux and her collaborators have identified nearly 400 cities for which they are working to compile data and have pinpointed four thematic policy areas that have been implemented in Latin America: mobility and emissions control, social inclusion, comprehensive urban development, and health behavior promotion. The project also supports six policy evaluations associated with a housing intervention in Chile, an urban redevelopment project in Brazil, the TransMiCable project in Bogotá, the Vision Zero and bike-share expansion projects in Mexico City, and a menu labeling initiative in Peru. The SALURBAL Project team has conducted participatory works to raise awareness of the project, the complex drivers of health, and the types of policies and interventions that could improve health and sustainability in cities (Diez-Roux et al., 2018). The team has also held several policy and dissemination events that brought together a wide range of nonprofits, private-sector stakeholders, local and national governments, and international organizations.

In closing, Diez-Roux said a tremendous opportunity exists for generating knowledge by creating data linkages, producing new data, mining and processing new and existing data, and using data for cross-city comparisons. Other opportunities include evaluating policies for their health and environmental impacts, building capacity in urban health sustainability research and action, disseminating and translating evidence into programs and policies, and creating partnerships that engage multiple stakeholders.

DISCUSSION

To start the discussion, Jo Ivey Boufford asked panelists to reflect on whether the presence of the private sector has changed over time. Diez--

Roux noted the private sector has shown increasing interest in these issues and has started exploring how it can partner in these efforts, but she has not yet seen increased involvement. Vlahov said he has seen more interest from the private sector in the economic opportunities and health benefits that could result from efforts to improve social and physical built environments. In particular, he saw promise in engaging the private sector in housing-related programs.

Haines said he sees great opportunities for members of the private sector to engage in several ways beyond their traditional roles in public transport and housing. Many businesses, however, still think traditionally. Instead, they could examine how new forms of housing can both reduce environmental footprints and create healthier and more sustainable indoor-household environments. Haines said, “We probably have not capitalized enough on those opportunities.” He added that he has seen emerging private-sector interest in bringing renewable energy options and food production options such as hydroponics and aquaponics to urban environments. He suggested mapping emerging areas in the private sector to see how the sector could best be engaged in these efforts.

Rebecca Martin from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention asked the panelists for their ideas on how the private sector and others might work with neglected, unincorporated areas that emerge when people move into urban areas but are not included in the governance structures of cities they abut. This problem, Vlahov replied, used to be solved by razing those settlements and hoping the people who lived there would leave, but as cities have become more enlightened about how to accommodate growth, they are considering other, more humane options. In fact, he noted efforts under way in Africa, India, and Latin America that deal successfully with this issue. Diez-Roux said that a similar governance problem is created when former residents of urban cores are displaced into peripheries as cities in the United States and elsewhere gentrify.

One strategy Haines and his colleagues have used in Kenya to address this issue is to support local governments in their bids for sustainable development funds, such as those from the Green Climate Fund.1 Haines said, “It is often quite difficult for low-income countries and cities to access those funds, so we have been trying to work with them through this work to help them in creating credible bids for funding. It is still too early to say how successful we will be, but if it is successful, then it will leverage new sources of funding into some of these informal settlements.”

___________________

1 Additional information is available at https://www.greenclimate.fund/home (accessed October 16, 2020).

Scott Ratzan, City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, asked panelists if the urban–rural digital divide plays any role in the differential health outcomes between urban and rural residents. Diez-Roux replied that researchers have not paid as much attention as they could to health impacts in this area. Nor have they really studied whether mass media and social media can play roles in reducing disparities. Haines noted that social media use is expanding greatly in low-income countries, where many people have mobile phones before they have settled accommodations, and health communications could make an impact in those areas. For example, he said that countries with a truly free press can more openly debate the pros and cons of different policies proposed to improve population health. He also pointed to the need for positive messages, particularly those directed at young people, about how to achieve development at lower levels of environmental impact than those achieved by richer countries.

John Monahan from Georgetown University commented that local-level authorities in the public sector’s formal government will exhibit enormous heterogeneity. He also wondered if that trend would provide an opportunity to learn about which government structures and formal authorities have allowed some places to be more or less successful in their attempts to address some of the cross-sector issues panelists identified in their presentations. Diez-Roux replied that this is, in fact, something that she and her colleagues are trying to characterize in the cities where they work. She noted the challenge is to determine how to measure the features of governance that make a difference. Vlahov noted that he had a chance to speak with about 50 mayors at an International Society for Urban Health meeting in Nairobi and found that some were simply implementers of national policy and had few resources at their disposal while others had more authority and resources to implement local policies. Regarding measurement, he said that disaggregating rural and urban data can be politically unpalatable for national leaders because doing so can highlight troubling differences.

Haines commented that governance at both local and national levels can be influential, particularly when they work together. Some actions, however, are difficult for cities to tackle alone. For example, without adequate national carbon pricing, cities experience difficulty scaling zero-carbon energy policies. At the local level, cities benefit from representational platforms that extend into local communities and into unincorporated or informal communities. Haines said, “Where you see effective city mechanisms for consulting with communities, you get more buy-in and can ensure that policies are attuned to the needs and perceptions of the local community, as well as representing national policy.” Another issue

that varies across countries is whether cities have any direct responsibilities to local health care sectors.

Charlotte Marchandise-Franquet, deputy mayor of Rennes, France, said that although mayors love smart city technology, she does not see many academics studying smart cities, nor does she see innovators working with all the data smart cities generate. These data could reflect the complexity of urban health and help policy makers—such as herself—gain insights that would potentially drive more effective health-related policies and activities. Diez-Roux agreed with that assessment and added that even basic data are not being collated, harmonized, and studied. She noted that she and her collaborators are now using remote-sensing information to characterize urban growth, an effort that requires a significant investment of time and money to extract meaning from messy data. Diez-Roux said, “I am convinced that there is meaning there, but I think we have to be careful that we do not use data in ways that can be obfuscating rather than illuminating.”

One problem, Vlahov said, is that researchers with backgrounds in medicine and public health do not interact much with engineers and computer scientists who work on smart cities. He said the best work is being done in well-developed, higher-income cities. Haines added that more people like Marchandise-Franquet, who embodies both technical and political expertise, need to be involved in research. He said, “We need people that can bridge that gap between academia and the frontline decision makers at the urban level, and we need to think about how we can strengthen the capacity to envelop more human resources, more people with those mixed experiences.”

Haines also said that when he and his collaborators tried to link health and environmental data from 250 randomly selected cities around the world, they found substantial data gaps—particularly from smaller, rapidly growing cities in Africa and Asia. Given that these cities will likely grow most over future decades, investment in data capture needs to occur for at least a range of these cities so that cities can be followed as they develop and expand. He also noted another issue: health and environmental data, when they do exist, are often held by different authorities and encompass different spatial scales. In addition, health data often involve confidentiality concerns with which ethics committees or institutional review boards may take issue. There are, Haines said, approaches for linking health and environmental data that maintain confidentiality, but they require some investment. Concerns about ideology are related to interactions between the public and private sectors, which he considers necessary to facilitate dialogue in order to grow innovation. For example, access to a specific geographic area may be needed to target malaria solutions to the exact location where cases occur. In this instance, the public

and private sectors could work together in order to make that area safe and accessible for health interventions. He also emphasized the importance of demonstrating proof of concept and of building partner trust. Parts of WHO’s new mission are to promote health and to serve the vulnerable, but these cannot be accomplished without dialogue. Singer said, “What you see in WHO now, and certainly with Dr. Tedros, is a humility and an openness to engage and to listen, and then to partner under those rules of engagement.”

Johnson asked Singer how he sees WHO’s role changing as populations shift and people move from the country to cities. Singer responded that this population shift “implicates all kinds of health shifts” and points to the important role of subnational and municipal governments in these transitions. WHO and its partners have some city-level activities, such as the Healthy Cities Network and the Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities, but Singer noted he has not yet seen an entity pull all of the activities together across schematics and sectors in order to use the platform of cities to deliver health. He saw an opportunity to look more systematically at a health issue, such as aging, noncommunicable diseases, air pollution, or obesity, at the municipal level.

This page intentionally left blank.