The four speakers featured in the workshop’s second session helped participants explore the evidence base from research on the effects of urbanization and urban planning on human health. First, Susan Parnell, global challenges professor in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol and emeritus professor at the University of Cape Town, introduced the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda. Next, workshop participants heard three short presentations from Mark J. Nieuwenhuijsen, director of the Urban Planning, Environment and Health Initiative and research professor in environmental epidemiology at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health; Eugénie L. Birch, the Lawrence C. Nussdorf Professor of Urban Research and Education, chair of the Graduate Group in City and Regional Planning, and founding co-director of the Penn Institute for Urban Research at the University of Pennsylvania; and Remy Sietchiping, leader of regional and metropolitan planning at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). In closing, Ann Aerts, head of the Novartis Foundation, moderated an open discussion.

THE CONTEMPORARY URBAN MOMENT AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR GLOBAL HEALTH

Susan Parnell (University of Bristol and University of Cape Town) noted that today is a useful time to stop and think about urban health because cities are primary; the planetary population is increasingly urbanized; and planetary constraints demand a shift in global health ideas, practices, and partnerships. She also explained that the spatial dynamics of development, which arise from increasing geographic population concentration, are changing the burden of disease and opening alternative entry points for disease mitigation. Parnell said, “What I am trying to

point out is that there are a number of reasons for why this is the moment to be rethinking urban health questions, the kinds of ideas we use, the practices we invoke, and the partnerships we bring to bear in restructuring urban health.”

Parnell explained that the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 11 and 3 underpin calls for a radical reframing of the urban determinants of health and for a new, commensurate, and integrated approach to global urban science and to global health. She said this underpinning concentrates the minds, efforts, and budgets of nation states as well as those of all other stakeholders engaged in all aspects of public health and health care. She remarked, “We have an opportunity to reconfigure the global agenda so that health becomes the global priority for urban health, and cities become the lens on health.” Achieving that reconfiguration, she added, will require thinking differently about the nature of urban health research and, critically, of translational research. She noted that for many urban scientists, the idea of designing systems for change is particularly foreign.

For Parnell, one needed change is not only to look at local evidence that speaks to a particular intervention’s effectiveness but also to aggregate results to identify strategic trends based on new types of global urban health data and data science innovation. She said, “Philosophically, we need to be able to shift our understanding of who is important, why they are important, what evidence they need, and how they need to be engaged in this translational research in new and different kinds of ways.” She also noted a wonderful opportunity, forged through consensus around the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,1 to use new forms of research practice and new research partnerships to achieve such a shift.

Parnell then spoke about one big challenge to acting on data to shift the global urban health agenda: the very nature of cities creates complexities around population diversity and entry points for reaching various city populations and constituencies. She said a relatively weak science base, massive geographical gaps in health care availability, and an inadequate understanding of interactions across urban systems combine to obscure central or core messages to deliver to urban populations.

One potential improvement within the New Urban Agenda, compared to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement on Climate Action, is its plan to develop a voluntary reporting process that connects better to local core stakeholders in cities. Each of these three initiatives provide mechanisms that may serve as platforms for identifying changes needed to improve health and well-being in cities

___________________

1 More information is available at https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2018/cities-2030--implementing-the-new-urban-agenda.html (accessed October 16, 2020).

globally. Simultaneously, the urban health caucus may need to organize itself in order to navigate the competing and complex institutional architectures of policy that influenced the often competing and complex aspirations in the 2030 Agenda. Organizing, she said, will create institutional heft and a set of agreed-upon priorities.

At present, Parnell said, there is no urban health equivalent to the mitigation/adaptation strategy pushed by the climate science community via the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Responding to increased urbanization, health adaptations could occur in areas such as family planning and reproductive health; air pollution reduction; walkability; transportation and mobility; road traffic safety; access to basic services such as water, sanitation, power, and waste disposal; food security; and urban health services.

Each intervention area will engage a vast domain of the private sector, Parnell added. Knowing where and how to make changes in the urban context will require harnessing scientific, medical, and operational expertise and reinvigorating the voice of public health officials in urban development plans. Parnell said, “We have a moment to resurrect the question of health and the relationship between the city and health.” Instead of focusing merely on water and sanitation, future discussions will need to focus also on energy, fertility, and pollution. These concerns will have to be embedded in law and will probably be embedded in the codes and practices of institutions and professions that ultimately run a city, she added.

Parnell was certain that big data and data science will play important roles in linking urban development and urban health. New data practices enable new ways to look at patterns and trends. She noted, in fact, that the most important partnerships to be forged around urban health will involve data generation and data access. Parnell said, “I would encourage you to be thinking critically as you engage with the New Urban Agenda about what the nature of health is and what the nature of knowledge is, because that is what will determine the practices that we embed in the city going forward.” Her suggestion to the workshop was to strengthen the capacity of urban health research to link to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and to associated international and national commitments. This will involve

- Harnessing/enrolling the private sector to build a credible and powerful consortium to drive urban health while ensuring public/open access to urban and health data;

- Focusing on areas where rapid urbanization and health problems will be greatest and where research capacity is least developed (i.e., Africa and Asia);

- Building scientific leadership that can synthesize existing urban knowledge and define gaps;

- Working locally in partnership with local governments and local service providers;

- Working nationally with specialists on natural urban policies; and

- Working globally to identify big lessons through composite and comparative research.

EFFECTS OF URBANIZATION AND URBAN PLANNING ON HEALTH

Although cities may be great, said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen (Urban Planning, Environment and Health Initiative; Barcelona Institute for Global Health), the urban planning related to human health that occurred as they grew has been less than optimal: Some cities are densely packed, and others sprawl over many square miles. Neither form, he noted, is good for human health—particularly because of the high levels of air pollution, due largely to heavy reliance on cars for urban transportation, associated with quite a few cities worldwide. Moreover, the negative effect of cars on human health extends beyond the pollutants they emit, Nieuwenhuijsen said. For example, when parked, cars occupy space on streets that could otherwise be used to plant trees.

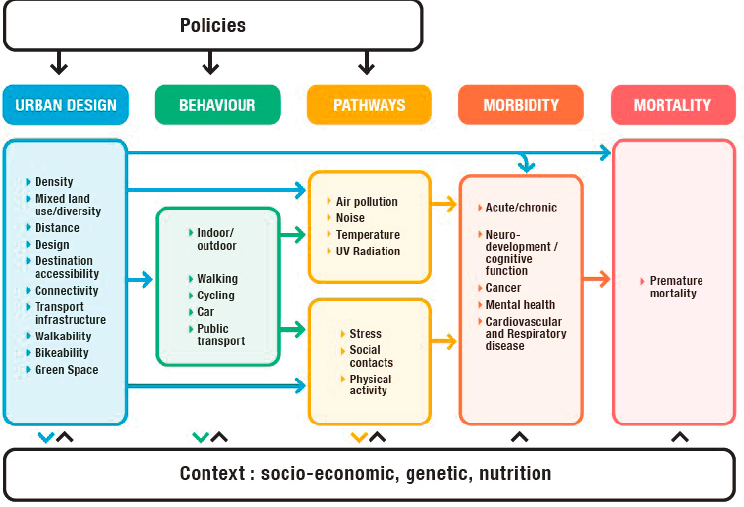

Today, robust understanding exists on the link between urban design, human urban movement, pollution pathways, and morbidity and mortality (see Figure 3-1). Nieuwenhuijsen said, “The point is that how we design the city determines how we get around and the levels of pollution.” For example, designing and investing in car-based urban infrastructure leads to cities with heavy car usage. In turn, such usage leads to higher air pollution and noise levels, a larger heat island effect, more stress, and reduced social contact and physical activity. Taken together, the result is increased morbidity and mortality among urban residents.

In contrast, Nieuwenhuijsen said, designing a city for bicycling and for other forms of active transportation yields a city where many more people cycle. That uptake in cycling leads to reduced air pollution, lower noise levels, less stress, and less space used by heat-absorbing roads—and hence to a smaller heat island effect. It also leads to more green spaces, social contacts, and physical activities. Morbidity and mortality would be expected to be lower as a result. Given the clear link between urban design and human health, Nieuwenhuijsen said, “We cannot put our heads in the sand anymore. We need to look at solutions.” His solutions involve land-use changes that reduce car dependency, increase public and active transportation, and create what he called green cities.

NOTE: UV = ultraviolet.

SOURCES: As presented by Mark Nieuwenhuijsen on June 13, 2019; Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016. CC BY 4.0.

In one 2016 study, researchers modeled projected health effects in six different cities—Boston, Copenhagen, Delhi, London, Melbourne, and São Paulo—if they were made 30 percent more compact (Stevenson et al., 2016). For all six cities, density increases led to health benefits ranging from 400 to 800 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100,000 people. However, compactness is not a cure-all: Barcelona, a very compact city, is not a healthy place, and a study Nieuwenhuijsen and his colleagues conducted estimated that the city’s heavy dependence on automobiles leads to 3,000 premature deaths each year. Barcelona, he explained, was originally designed in the 1800s with human health in mind, and it relied on wide streets with green spaces in the middle of blocks. Unfortunately, he said, these streets started filling with cars in the 1960s, and the green spaces became garages or other structures.

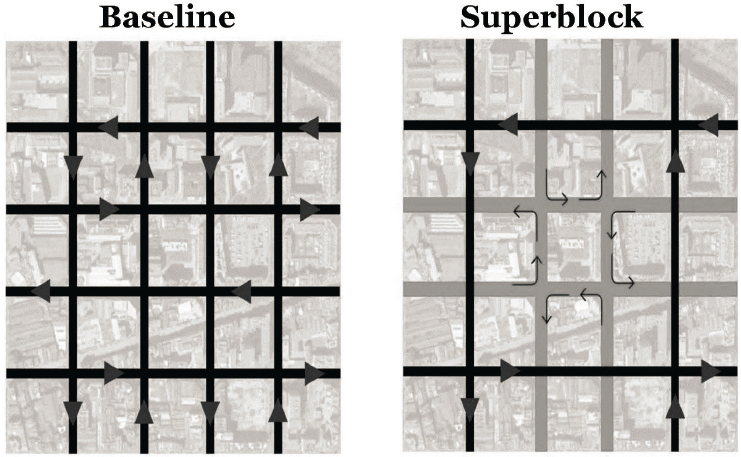

One solution to this problem is the superblock construct (Mueller et al., 2019), which reclaims public space from cars by changing traffic flows so that cars can drive into but not through multi-block sections of a city (see Figure 3-2). Modeling what superblocks would achieve in Barcelona, Nieuwenhuijsen and his colleagues found superblocks would

SOURCES: As presented by Mark Nieuwenhuijsen on June 13, 2019; Mueller et al., 2019. CC BY 4.0.

reduce car usage by 19.2 percent, nitric oxide levels by 24.3 percent, noise levels by 2.9 decibels, and surface temperature by 20 percent. They would also increase green spaces in the city from 6.5 percent to 19.6 percent. Together, these effects would prevent 700 premature deaths per year without accounting for any benefits that would accrue from people walking or riding bikes more.

The United Kingdom’s Vision 2030 Walking and Cycling Project,2 which examined the effect of different street designs on human health, found that redesigning urban transport to rely more on active transportation options—biking and walking—and adding more green spaces would save between 8,000 and 9,000 DALYs per 1 million people (Woodcock et al., 2013). Nieuwenhuijsen said, “By changing the design of what we have in cities, we actually can generate quite large health benefits.”

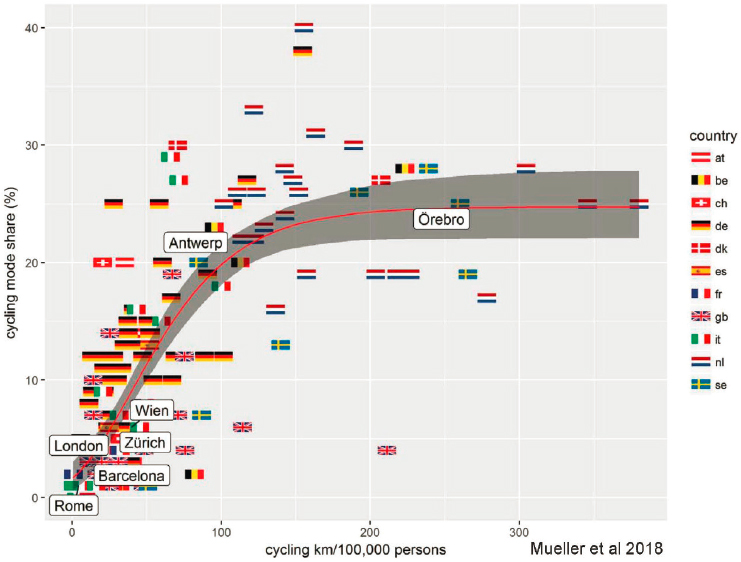

Dedicated cycling lanes can also benefit urban dwellers’ health. One study that Nieuwenhuijsen and his colleagues conducted found a direct relationship between the length of cycling lanes per 100,000 people in

___________________

2 Additional information available at http://www.visions2030.org.uk (accessed October 16, 2020).

167 European cities and the mode share of cycling (i.e., the percentage of urban residents who use bikes regularly)—up to about 25 percent mode share (see Figure 3-3). When they then modeled what would happen if cities could reach 25 percent mode share for cycling, they estimated that doing so would prevent more than 10,000 premature deaths per year. Nieuwenhuijsen said, “Again, you can prevent quite a number of deaths by changing your environment within cities.”

Making such changes to a city requires active citizen participation, he noted. For example, the residents of Antwerp, Belgium—a city of 500,000 people with 30,000 vehicles driving each day on a motorway that crosses the heart of the city—worked with scientists and policy makers to generate an idea: put the motorway underground, and create large green spaces over the subterranean road. Public crowdsourcing raised 200,000 euros to support the project’s planning stage, and project leaders involved locals by having 2,000 residents collect air samples to determine pollution levels. These residents were also invited to planning sessions devoted to discuss-

SOURCES: As presented by Mark Nieuwenhuijsen on June 13, 2019; Nieuwenhuijsen, 2016. CC BY 4.0.

ing the health effects of air pollution. A health impact assessment estimated that 21 deaths per year would be prevented within a 1,500-meter radius of the underground road—not accounting for any benefits afforded by green spaces created by the project (Van Brusselen et al., 2016).

Nieuwenhuijsen noted that Antwerp’s project is ongoing and that other cities, including Seoul and Barcelona, are moving urban motorways underground. Some cities, such as Hamburg, even aim to be car-free, which he called a pathway to healthy urban living (Nieuwenhuijsen and Khreis, 2016). Though he admitted difficulty imagining a U.S. city going car-free, he noted such action is more likely to happen in Europe. In fact, Freiburg, Germany, has already become car-free.

In his experience as a public health researcher, Nieuwenhuijsen said that urban and transport planners rarely think about health, even though their actions largely impact health. In closing, he said urban and transport planning needs more sectoral and systemic approaches that include input from businesses, the housing and health sectors, citizens, educators, architects, and environmental experts and emphasize making cities healthier as the core goal.

DESIGNING PUBLIC SPACES FOR HEALTHIER LIVES

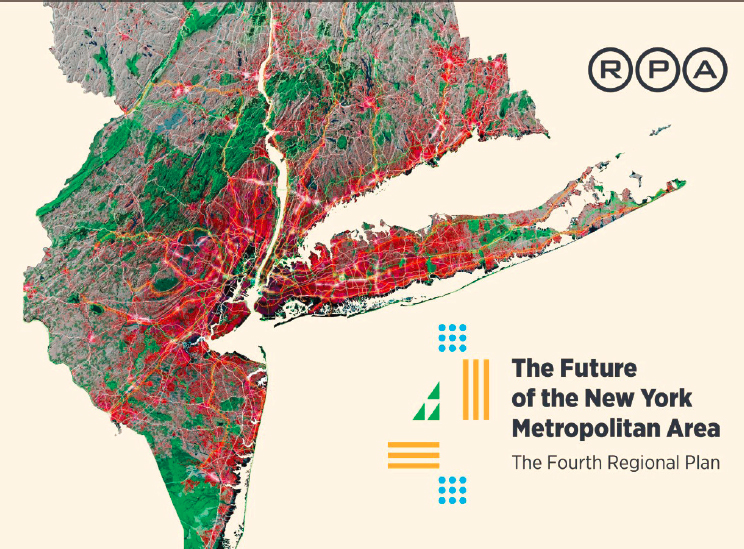

The focus of Eugénie Birch’s (University of Pennsylvania) presentation was on designing public space, which she defined as a place accessible to all citizens for their full use and enjoyment. Streets are an obvious public space, one that needs to serve walkers, bicyclists, and drivers, and they should include safe crosswalks, a planting strip, and green spaces. She illustrated the concept of Complete Streets, a design philosophy that advocates a comprehensive approach to safely incorporating all users from vehicles to pedestrians. This model considers the entire public space, from active sidewalks and roadways, to dedicated bike lanes, safe crosswalks, planting strips, and green spaces. Other public spaces in a regional context include green spaces to protect water and food supplies as well as wetlands and coastal areas to protect against flooding. She asserted that the Regional Plan Association’s The Future of the New York Metropolitan Area: The Fourth Regional Plan exemplifies this thinking as its portrait of the region illustrates. It shows population centers (red) and the many green spaces (green) that sustain urban development on the regional scale (see Figure 3-4).

Public spaces, Birch said, can also have ceremonial purposes and can serve as gathering places that encourage socialization. They can even generate opportunities for people to make a living through vending operations. Children need public spaces—a fact recognized in the late nineteenth century when reformers successfully advocated for including playgrounds in urban schools.

SOURCES: As presented by Eugénie Birch, June 13, 2019. Used with permission from the Regional Plan Association.

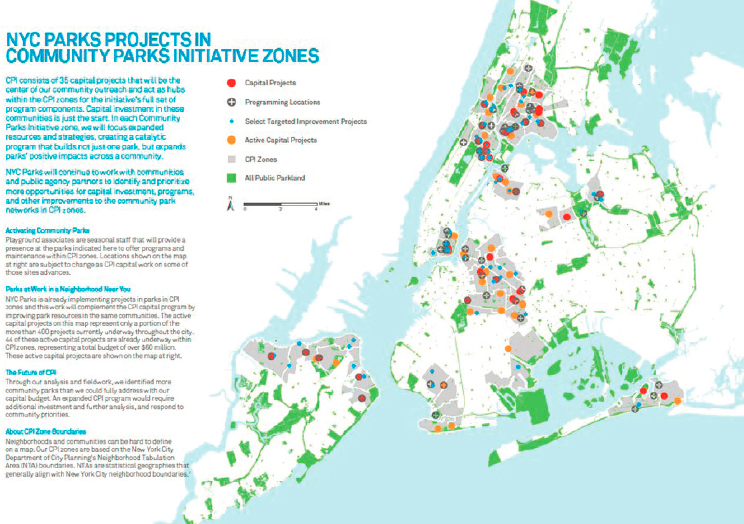

Birch said it is important to incorporate a variety of voices, including those of community members, into discussions when designing spaces for public use. For example, in New York City, with its high proportion of immigrants, community input has incorporated different visions among new residents about how they would use public spaces. For instance, people have called for soccer fields and cricket pitches in place of football fields. Furthermore, the current New York City Department of Parks & Recreation Commissioner, Mitchell Silver, the first city planner to administer the Department of Parks & Recreation, successfully lobbied for budget increases to prioritize the city’s capital expenditures in immigrant and/or low-income communities. The Department of Parks & Recreation labeled the program the Community Parks Initiative, outlined large zones around parks, and targeted other investments in those areas to catalyze broader economic and environmental improvements. Figure 3-5 illustrates the 35 designated zones, all of which are in economically disadvantaged areas.

Other places, especially Legacy Cities in the U.S. Northeast and Midwest where population losses have left cities with acres of abandoned

SOURCES: As presented by Eugénie Birch, June 13, 2019. Used with permission from New York City Department of Parks & Recreation.

land, have developed public space programs. In Philadelphia, for example, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society has engaged in a public–private partnership (PPP) to green many of the city’s 40,000 vacant lots and to create healthier environments for affected neighborhoods (Kondo et al., 2018). Approximately one-third of the vacant lots have been turned into green spaces, and neighborhoods where conversions have occurred have seen a significant decrease in residents’ self-reported feelings of depression and worthlessness (South et al., 2018).

Birch concluded by suggesting more research is needed to firmly establish the key benefits of public space and health. She called on participants to find common questions with which to guide shared research drawn across the many disciplines that are concerned with the built environment and its effects on people.

HEALTH-FOCUSED URBAN AND TERRESTRIAL PLANNING

The UN Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), explained Remy Sietchiping (Global Solutions Division, UN-Habitat), aims to con-

nect people with the spaces in which they live and, in doing so, to improve air quality, spatial inclusion and equity, resilience, food security, lifestyle, and nutrition while reducing sprawl and risk exposure. Health, said Sietchiping, is affected by those connections across different scales, from the household to the city and the nation—and even the globe when considering health effects from climate change. Changing how people interact with and benefit from the spaces in which they live requires a multi-stakeholder approach that engages local citizenry and creates public–private–people partnerships. It also requires health actors and urban actors to work together rather than in isolation.

Turning to the subject of the UN’s New Urban Agenda, Sietchiping said that health has become a central metric for the agenda (UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, 2016). Sietchiping noted that SDG 3, which focuses on good health and well-being, and SDG 11, which focuses on sustainable cities and communities, are strongly interlinked. He and his colleagues have been working with the World Health Organization to prepare a sourcebook on urban territorial planning that will emphasize health. They are also developing an assessment tool that examines the effects of transportation choices on urban health. Going forward, they will emphasize implementing interventions in urban planning that can contribute to well-being. Sietchiping explained that in some regions of the world, such as in Africa, spiritual health is an important component of well-being for many people.

In both Cameroon and Uganda, UN-Habitat has brought together urban planners and health care providers to work on urban planning practices that can benefit health. The challenge has been developing a common language that can bridge gaps between these two communities. However, bridging that gap can produce success—as was seen in a project designed to reduce the incidence of malaria and dengue fever.

DISCUSSION

To start the discussion, moderator Ann Aerts asked panelists to suggest the one action mayors should address first given their limited resources. Nieuwenhuijsen replied that creating environments that would enable city residents to increase their physical activity would have the biggest positive effect on health. Doing so, however, would first require eroding silos that prevent public health experts from working with urban and transport planners on a common agenda. He noted that change is not always expensive. Barcelona, for example, erected plastic barriers on existing roads to create separate cycling lanes, which led to an increase in people riding their bikes rather than driving their cars. Sietchiping agreed that improvements that benefit health do not have to be expensive.

However, Birch said that although this type of approach might work in Barcelona, poverty and unemployment need to be addressed first in many parts of the world.

David Vlahov from the Yale School of Nursing and School of Public Health commented on the importance of input balance in PPPs and on the need for a common language across the many different professions and disciplines integral to improving public health through better urban and transportation planning. He then asked panelists if any of the underground projects include technologies that can capture the carbon dioxide emitted by vehicles traveling through subterranean motorways. None of the panelists were aware of any such efforts. Birch suggested the idea is probably not even considered because, for example, these projects are designed by transportation planners with little input from environmental engineers.

Jo Ivey Boufford remarked that many organizations, and particularly hospitals, have large urban campuses with huge parking lots that would afford opportunities for creating more usable, health-promoting spaces. She then asked panelists to comment on how to address equity in the context of urban planning. Birch replied that conversations about equity are not occurring—particularly not in the developing world where informal settlements with no open spaces or places to congregate account for 40 to 50 percent of a city’s land mass. Parnell agreed with Birch that different cities will require different transformations to improve health and equity but added that some of the most important levers of change lie with national governments or even with global corporations. Therefore, creating linkages that extend beyond those of city governments becomes imperative. Nieuwenhuijsen noted that cities that are adding more green spaces are also encountering environmental gentrification, a situation that makes equity worse instead of better and provides strong evidence for including community organizations in planning processes.

Katherine Taylor from the University of Notre Dame commented that making the types of changes panelists addressed requires long-term planning and large investments. Given that the public sector can be quite inconsistent with its commitment to certain values and principles, she asked panelists if they could see the private sector providing a longer-term vision and commitment to change or if the private sector’s commitment would be even shorter than that of the public sector. Birch said that depends on the PPP’s governance structure, one that includes an active, united civic community that holds partners to their commitments. Nieuwenhuijsen believed the private sector generally has a short-term vision given its emphasis on quarterly and yearly profits, while the public sector has to consider election cycles. The community, he said, has the long-term vision given that most people live in the same community for decades.

One problem Birch encountered when she was a member of the New York City Planning Commission was the “not in my backyard” phenomenon. She said mediating arenas are needed: Places where different interests can negotiate with each other given their individual motivations. Nieuwenhuijsen noted that bringing people together from different backgrounds and with differently vested interests is not easy. To address this problem, he and his colleagues have created a knowledge translation group to speak with urban planners and other interested parties about what they have learned as researchers in order to create common ground for future discussions. Also helpful, said Parnell, is identifying ways of incentivizing different constituencies to come to the table to discuss urban health issues.

Charlotte Marchandise-Franquet noted that public opinion can drive the public sector’s involvement in a project. In that respect, she believes that mayors can be effective mediators if they are empowered with information from research. Nieuwenhuijsen, sympathizing with the difficult job elected officials have as mediators, acknowledged that large gaps can occur between what academic research finds and what can actually be implemented in a city. The missing component, he said, is knowledge about how to translate and implement research findings in urban environments that have multiple stakeholders with multiple motivations for changing or maintaining the status quo.