The workshop’s third panel session featured presentations about urban health inequities. The panelists were David Napier, professor of medical anthropology and director of the Science, Medicine, and Society Network at the University College London and global academic lead for Cities Changing Diabetes; Karin Cooke, director of Kaiser Permanente International and director of technology innovation and the innovation fund for technology at Kaiser Permanente; and Geoffrey So, head of strategy and global health policy at Novartis Foundation. After the three presentations, Rebecca Martin, director of the Center for Global Health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, moderated an open discussion with workshop participants.

IDENTIFYING AND ADDRESSING HEALTH INEQUITIES IN THE CITIES CHANGING DIABETES INITIATIVE

Worldwide, 437 million people live with diabetes, and that number is projected to soar to more than 642 million by 2060. To put these numbers into context, David Napier (University College London) remarked that if diabetes were a country, it would be the third most populous one on the planet. What makes this an urban health issue, he added, is that 65 percent of people with diabetes lived in cities in 2017, and that number is expected to increase to 75 percent by 2045 (IDF, 2017). Moreover, because cities are complex, dynamic, and often mutable, diverse drivers can affect illness and lived experience, particularly given that health inequalities are, in general, exaggerated in social environments under stress—which includes most of the world’s cities.

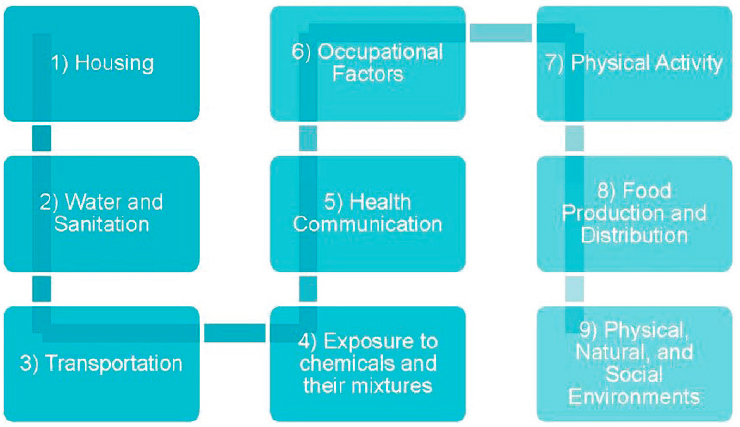

Addressing the growing incidence of diabetes will require a Health in All Policies approach, Napier said. In considering the Health in All Policies framework at the World Health Organization (WHO) (see Figure 4-1),

SOURCES: As presented by David Napier, June 13, 2019. Original author, Anna-Maria Volkmann. Used with permission from David Napier.

he noted that diabetes relevant risk factors are present in each of its policy domains. For example, in the transportation domain, long commutes to work can leave little time to exercise, and crowded, inadequate housing can limit residents’ abilities to move and be active. Some domains, he explained, contain significant data on which to build a research and intervention agenda while others lack data related to health and health impacts. Conducting randomized controlled-type research is not possible in these domains because no single cause of diabetes exists; rather, compounding causes significantly exacerbate each other.

As an aside, Napier briefly mentioned the decision of the United Nations (UN) Global Compact, which monitors ethical and workplace practices at more than 600 businesses worldwide, to develop a taxonomy of public–private partnerships. This taxonomy would allow the Global Compact to see how businesses become vulnerable and to engage the public in promoting good health and well-being to address UN Sustainable Development Goal 3. He mentioned this effort to show room exists to talk about different kinds of businesses and about things they can and cannot do to promote public health.

In that context, Novo Nordisk invited Napier and his colleagues to join one of its new initiatives—Cities Changing Diabetes—in collaboration with Steno, a world-leading institution in diabetes care and prevention. The program seeks to engage different cross-sector partners in address-

ing the diabetes and obesity challenge through discovering actionable insights into health vulnerabilities among at-risk populations, creating opportunities for disseminating those findings through new knowledge networks, and working with local and global advocates to reverse the diabetes and obesity epidemics. Over the past 5 years, 22 cities have partnered with the Cities Changing Diabetes initiative, and Napier expects that number to more than double over the next 5 years. He hopes the data from these partners will produce comparable datasets that the program can analyze to develop and share best practices. Although working across sectors is challenging, he noted, it is also urgent. He presented an example: Unchecked diabetes-related mortality and morbidity are projected to bankrupt Mexico’s health care system over the next 15 years.

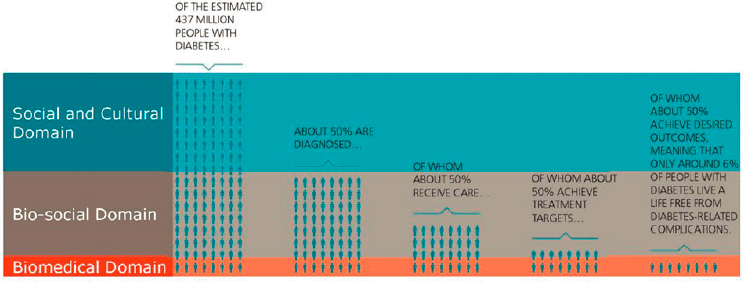

Driving this research effort is what is called the Rule of Halves (Hart, 1992; see Figure 4-2)—of the estimated 437 million people living with diabetes, only about half are diagnosed, and of that number, only about half receive care. Moreover, only half of those who receive care achieve their treatment targets, and only half of these individuals achieve desired outcomes (Cities Changing Diabetes, 2017b). This final “half” of people with diabetes live without diabetes-related complications, but that number can vary from less than 40 percent to less than 1 percent depending on the health care system in question. In essence, much of the money funneled into diabetes prevention and treatment is wasted. Napier said, “This really is quite a devastating indictment against what we are doing to halt this epidemic.”

In the Rule of Halves, the biomedical domain comprises individuals for whom none of the associated non-biomedical risk factors are very

SOURCES: As presented by David Napier, June 13, 2019. Original author, Anna-Maria Volkmann. Used with permission from David Napier.

important—because they are doing well, whether they are rich or poor, well educated or not. The bio-social domain comprises what Napier calls the ground of non-adherence: people who are diagnosed with diabetes but are not managing it. The social and cultural domain includes individuals who are unaware they have diabetes and for whom, therefore, the illness experience remains entirely non-medical.

To better understand diabetes, Napier argues, we need a new approach that examines and measures the environmental, social, psychological, and cultural risk factors that contribute to diabetes, especially in urban settings; identifies people who are most vulnerable to these risk factors; and determines what can be done to make those individuals and groups less vulnerable. Toward this end, Napier’s team has developed a vulnerability assessment tool. This tool examines service-use patterns and barriers, including biological, social, geographical, and cultural factors, that prevent people from changing their behavior. The goals in using this tool are to understand how vulnerability emerges in a particular city, to identify new and measurable case definitions of diabetes vulnerability, and to find ways of bringing the lived experience to the level of evidence.

In Houston, for example, Napier’s research colleagues discovered that groups at the highest risk for diabetes include not only people who are poor but also those who are affluent and professionals who are well educated and live commuter lifestyles. Houston is also a city where faith-based organizations serve as a rich resource for people who are learning to manage their illnesses. In Shanghai, those most at risk are members of middle-class families who consciously conceal early symptoms because of social stigma and fear about losing their jobs or spouses. In Vancouver, Napier’s colleagues found that food insecurity causes more than 850,000 Canadians to rely on food banks and eat unhealthy foods. That finding led the city to initiate onsite dietary counseling at its food banks. The research team in Copenhagen found that alienated middle-age men carry a high and unequal diabetes burden even though health care is free and health care registration is mandatory. The city has established community-based social clubs to bring people who live in isolation together to share their diabetes challenges. In each case, locally based research on the social drivers of health vulnerabilities has, with public–private support, led to rapid implementation of specific programs designed to reduce the prevalence of obesity and/or prediabetes and to improve outcomes for people who live with diabetes.

COMMUNITY HEALTH: IMPROVING HEALTH FOR ALL

As a nonprofit health care organization, explained Karin Cooke (Kaiser Permanente, also referred to as Kaiser), Kaiser takes what it calls a

community health approach, which aims to improve the health of its 12.3 million members as well as the health of the 68 million other residents in the communities it services. Toward that end, she noted, Kaiser Permanente has established seven community health priorities: affordability and access, social care, housing and homelessness, wellness in schools, economic opportunity, public policy, and environmental stewardship. The vision for its community health program is to use data to connect people with appropriate resources.

Cooke said Kaiser particularly emphasizes public policy, and its CityHealth initiative, a collaboration with the de Beaumont Foundation, supports the 40 largest U.S. cities in their efforts to develop policies that bolster good health and quality of life. For example, these policies aim to make streets more accessible for physical activity and to provide more affordable housing and stable employment. One exemplar city, Washington, DC, has already implemented five or more policies in many of the emphasized areas. As a result, Cooke said, it has seen some health gains.

Data from years of Kaiser Permanente’s community health needs assessments indicate that many members have unmet health and social needs: more than 40 percent experience financial strain, 25 percent deal with food insecurity, and 23 percent have issues with housing (Hamity et al., 2018; Sundar, 2018). Cooke noted that although regions vary, these three social needs consistently rank as most prevalent. She also explained that social needs information is now integrated into Kaiser’s electronic health record (EHR). Because social issues are flagged in the same way as health condition alerts, the system’s providers are able to link social and medical needs. Cooke said, “What has always been challenging with this is that once the doctors knew there was a social need, then what?”

In 2019, looking beyond its members, Kaiser surveyed more than 1,000 nonmembers to discover their views on social needs, health impacts, and community-resource usage (Kaiser Permanente, 2019). The survey results showed that 55 percent of U.S. residents view social needs as an integral part of overall health and that 97 percent want their medical providers to ask them about social needs and connect them with resources. More than one-third of the survey respondents said they lack confidence in their abilities to access resources and address social needs on their own. Cooke noted, “One-third of all U.S. residents experience some stress related to social needs, so this is clearly an issue that impacts overall community health.”

Responding to these findings, Kaiser launched a new program called Thrive Local: Addressing Social Needs for Total Health. This program takes what Kaiser has learned about how to connect its members to social needs and attempts to turn those lessons into a scalable system. Thrive Local comprises a resource directory that provides information on social

services and public benefits, geographic community partner networks to which providers can refer their patients, and a technology platform that allows for two-way, closed-loop referrals and integration into EHRs and community-based organizations’ client-management systems. This last component will allow care teams to receive feedback on whether their patients use these resources. Thrive Local, said Cooke, is available for all community-based organizations to use for free. Kaiser is also inviting other health care systems to join the program.

Turning to the subject of affordable housing and homelessness, Cooke noted that Kaiser operates in 6 of the 10 U.S. cities with the largest homeless populations. After examining this immense challenge, the organization identified several ways to address it. Through a partnership with Community-Based Solutions, for example, Kaiser is working in 15 communities to end chronic homelessness by using data analytics to identify solutions that would work best for homeless individuals. Kaiser is also investing $200 million to increase the supply of affordable housing, Cooke added.

BETTER HEARTS BETTER CITIES

The Novartis Foundation’s Better Hearts Better Cities initiative aims to improve cardiovascular health in low-income urban populations through a multidisciplinary approach that addresses hypertension and its underlying determinants, explained Geoffrey So (Novartis Foundation). He noted that hypertension kills 10 million people per year worldwide, and 75 percent of those deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. The program’s approach is to build a network of partners in three demonstration cities—Dakar, Senegal; São Paulo, Brazil; and Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia—that reaches beyond the health sector, integrates capacity in existing health systems, and leverages complementary expertise and resources to co-design and implement interventions. In each city, the prevalence of hypertension is 30 percent or more, and cardiovascular mortality affects from 16 percent of the population in Dakar to 40 percent in Ulaanbaatar. In Ulaanbaatar, 60 percent of the 1.4 million residents live in informal settlements with significant health disparities and with high levels of premature cardiovascular mortality.

Better Hearts Better Cities has five pillars: fostering strong local ownership of multi-stakeholder partnerships that include government agencies, civil society organizations, and implementation agencies; establishing a quality-improvement culture for health and care; enhancing the performance of local health systems; delivering health and care closer to where people live, work, and play; and implementing policies aimed at addressing urban cardiovascular health. So noted that the government in

Dakar asked the Novartis Foundation to create a national plan for cardiometabolic diseases and a national digital health strategy. As part of this effort, Novartis successfully advocated for community health workers to assume the task of screening for hypertension and following up on treatment recommendations while also working with community leaders and patient representatives to increase literacy about early diagnosis and healthy behaviors. In addition, the program introduced a standardized algorithm, patient records, a registry for hypertension, and a digital dashboard to facilitate real-time availability of patient and program progress. Senegal also improved access to hypertension medications after the national pharmacy adopted an essential drug list.

In Ulaanbaatar, one finding at the start of Better Hearts Better Cities was that most hypertension patients were unaware of their condition. Two years later, after the implementation of significant health system strengthening activities, more than 80 percent of the population is now screened for hypertension, and more than 30 percent of those screened are diagnosed with hypertension. To address initial gaps related to chronic care in the health system’s performance, Better Hearts Better Cities developed a comprehensive digital health platform with patient trackers, clinical decision support, an electronic prescribing function that simplified care coordination, and communication capacity between levels of care. It also made real-time data available to both health managers and policy makers at the Ministry of Health and the National Health Insurance office and engaged pharmacists in hypertension detection and care. Working with local health authorities, the Novartis Foundation and its partners developed solutions for process optimization and systematic hypertension screening in clinics. They also developed digital applications to enhance patient self-management. These efforts, said So, improved the performance of the health care system in Mongolia so that 77 percent of people diagnosed with hypertension now receive treatment, and most patients have their blood pressure under control. He added that Mongolia passed a tobacco tax and used those funds to increase financial support for primary care institutions by 300 percent.

In São Paulo, the program partnered with local champions such as the Corinthians Football Club and the city’s many samba schools to increase awareness of hypertension and heart health and to conduct screening campaigns on football match days and during carnival parades. It also facilitated implementing health literacy programs and physical exercise in schools; trained lifestyle advocates at several companies in local communities; and partnered with community leaders to advocate for early diagnosis and treatment and to encourage behavioral change.

On a final note, So commented that when Better Hearts Better Cities started in Ulaanbaatar, it enrolled 25 out of 142 clinics in the city to test

and refine the initiative. The program was rolled out to the entire city 1 year later and began spreading throughout the country in 2019. In the wake of the program’s success, the World Bank contributed additional investment to reinforce the country’s newly constructed digital health system.

DISCUSSION

Rebecca Martin, moderator, began the discussion by asking panelists to talk about strategies they have developed to address the use of data collected by their partners. Cooke replied that Thrive Local’s partners each have their own client management systems, so Kaiser developed a way to integrate data in those systems with its EHRs after years of effort. As a result, all partners now have access to the same data. So noted that putting systems in place to integrate data from different partners and then making that data available to partners has helped the partners understand their prior gaps in knowledge. This has empowered clinics and patients to educate themselves and allowed clinics to provide higher quality of care.

John Monahan from the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy asked Cooke if Kaiser helps under-resourced community organizations implement the technologies they need to participate in the program. Cooke replied that Kaiser is concerned about stressing community systems, so it does invest in community organizations. She hoped that creating an open platform would encourage other systems to join and see the need to support these organizations. She noted that Kaiser is incentivized to invest in the community because it is a nonprofit and because it does better when the entire community is healthier.

So commented that he and his colleagues are working with food and agriculture companies that are trying to leverage technology in a way that will enable farmers to pool their resources and sell their produce as an aggregate for better pricing. Their idea is to link supply information with the demand for healthier food that Better Hearts Better Cities creates in workplaces and schools.

David Vlahov from the Yale School of Nursing and School of Public Health asked So who he first approached in Mongolia to start his program. So replied that he first spoke to national health authorities and to the mayor of Ulaanbaatar to see whether they would be receptive to such a program, and they were. At the same time, he and his team were fortunately introduced to and then worked with an organization that had a history of implementing policies in Mongolia.

This page intentionally left blank.