The fourth workshop panel focused on the role that food, agriculture, and transportation systems play in determining the health of urban populations. The three panelists were William Dietz, professor at the Milken Institute School of Public Health and chair of the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness at The George Washington University; Allison Goldberg, executive director of the AB InBev Foundation; and Olga Lucia Sarmiento, professor in the Department of Public Health at the School of Medicine at the Universidad de Los Andes. Rebecca Martin moderated an open discussion that followed the three presentations.

THE GLOBAL SYNDEMIC OF OBESITY, UNDERNUTRITION, AND CLIMATE CHANGE

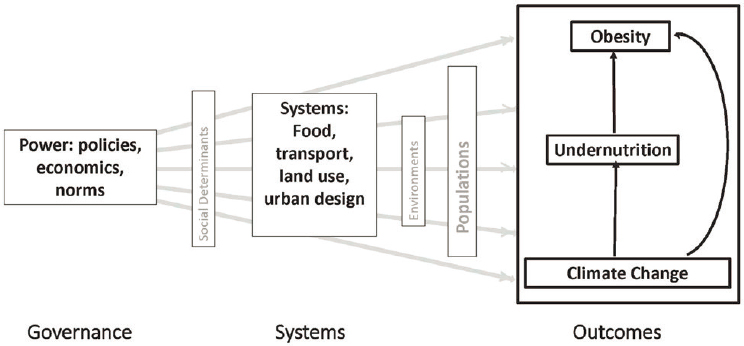

William Dietz (The George Washington University) opened his presentation by defining the word syndemic, a new term within medicine but an old one to anthropologists, which refers to the synergistic interactions between epidemics or pandemics. In this case, Dietz used the term to characterize negative interactions over time and place between the pandemics of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change. Such interactions also have common economic, social, political, or environmental drivers that include food, transport, urban design, and land-use systems (Swinburn et al., 2019) (see Figure 5-1). Dietz said, “We consider climate change as a pandemic because of the breadth of its effects on health.” Taking this perspective is important, he added, because it creates opportunities for double- and triple-duty solutions.

Dietz explained examples of how this syndemic operates: Increased greenhouse gases produced largely by agricultural systems, which account for 23 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, increase temperature, rainfall variability, and instances of extreme weather, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. These variations, in turn, affect crop yields, reduce the nutritional content of foods, and trigger price increases, all of which combine to alter nutritional status. He said, “If you think about the marginal status of nutritional production in low- and middle-income countries, these are particularly going to be affected and become increasingly reliant on imported food largely in urban centers for their sustenance.”

All countries, he noted, are experiencing an increase in obesity, but undernutrition worldwide has somewhat declined over the past 30 years. In his opinion, one of the most important drivers of rising obesity has been the advent of supermarkets and alterations in the food supply. These factors have resulted in increased consumption of ultra-processed foods, heavily marketed worldwide, which leads to increased body weight (Hall

SOURCES: As presented by William Dietz, June 13, 2019. Used with permission from William H. Dietz, Sumner N. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness, The George Washington University; adapted from The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition and climate change; Lancet 2019; 10173:791–846.

et al., 2019; Mozaffarian et al., 2011; PAHO, 2019). Supermarkets were introduced in urban centers some 20 years ago, coincident with increased production of ultra-processed foods, which may be one reason for the higher prevalence of obesity in urban centers compared to the prevalence in rural areas. He said reduced physical activity is also likely to blame, but that is a harder problem to solve; it requires changes in a community’s infrastructure, as several workshop speakers had already noted.

Ultra-processed foods, particularly those produced from corn, have a major adverse effect on the environment, Dietz said. Corn production is heavily dependent on fertilizer and pesticide applications, and, as flooding in the U.S. Midwest in 2019 demonstrated, these chemicals can run off into waterways and harm ecosystems distant from farm fields. Ultra-processed foods are also convenient, tasty, and inexpensive and have long shelf lives, all of which make them particularly appealing in low-income communities that lack easy access to fruits and vegetables. He also noted that fast food sales increase as countries increase their wealth.

According to the NOVA classification of foods (Monteiro et al., 2017, 2019), ultra-processed foods are those made from industrial substances with little or no whole foods, and they include sugary drinks, cookies, and packaged soups, noodles, or snacks. Again, corn production is a factor because of the amount of high-fructose corn syrup found in sugary drinks. Ultra-processed foods, he noted, are associated with decreased

satiety—the feeling of having eaten enough—compared to unprocessed foods, and lower satiety likely leads to increased calorie consumption.

To conclude his presentation, Dietz listed possible approaches to reducing consumption of ultra-processed foods. These included redirecting subsidies away from supporting corn production and toward supporting production of low-cost, healthy alternatives. Shifting subsidies in this manner would increase the cost of ultra-processed foods, reduce demand for them, and better reflect their true costs. Restricting the marketing of ultra-processed foods is another approach, one that a few countries such as Colombia and Mexico have used in the face of industry resistance. Another strategy would be to implement food labels with both nutritional and sustainability information. Dietz said taking these actions would result in triple-duty consequences such as healthier diets for obesity prevention, more land for sustainable agriculture, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and transport of ultra-processed foods.

In closing, he also noted that changes in urban design, land use, and transport systems could also have triple-duty consequences for reducing obesity, undernutrition, and greenhouse gas emissions. Steps in that direction include redesigning infrastructure to support physical and public transport systems, reducing subsidies for fossil fuel production, increasing gasoline taxes, and engaging in social marketing.

POTENTIAL TRANSPORTATION SOLUTIONS

The harmful use of alcohol is a global problem, began Allison Goldberg (AB InBev Foundation), and both the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have recognized that alcohol use is a leading risk factor for noncommunicable diseases worldwide. The contribution of alcohol to noncommunicable diseases may be even more acute in urban areas than in rural regions, she added. Germane to this workshop, the UN has proposed that public–private partnerships (PPPs) are needed to reduce the adverse effects of harmful drinking.

In response to this call for PPPs, AB InBev launched its Global Smart Drinking Goals in December 2015 and aimed to create a new norm around smart drinking as well as a culture in which harmful drinking is deemed socially unacceptable. Two of the goals are designed to empower consumers through choice by ensuring that no- or lower-alcohol beer products represent at least 20 percent of AB InBev’s global beer volume by the end of 2025 and by placing a guidance label on all of its beer products by the end of 2020 as a way to increase alcohol health literacy by 2025. Two other goals seek to influence social norms and individual behaviors in order to reduce harmful alcohol use. To achieve this, AB InBev is investing at least $1 billion worldwide by 2025 in dedicated social marketing cam-

paigns and related programs. It will also conduct pilot programs to reduce the harmful use of alcohol by at least 10 percent in each of six cities as a way to develop best practices globally by 2025 (Georgetown University and AB InBev Foundation, 2020).

In addition, with an initial commitment of $150 million over 10 years, AB InBev created the AB InBev Foundation in 2017 to oversee the pilot programs in each of the six cities. Currently, the foundation spearheads pilot programs in Brasilia, Brazil; Columbus, Ohio; Jiangshan, China; Johannesburg, South Africa; Leuven, Belgium; and Zacatecas City, Mexico, where it tests a model of PPP with multiple stakeholders and sectors that include the alcohol industry. The foundation, Goldberg noted, is committed to supporting evaluation and to sharing all lessons that emerge from programs in these six cities.

Goldberg discussed the pilot in Columbus, Ohio, in some detail. This pilot was launched at the end of 2016 with a steering committee representing the mayor’s office, The Ohio State University’s College of Public Health, AB InBev’s corporate social responsibility division, Columbus Distributing & Delmar Distributing, the city’s epidemiology office, and the city’s family health administrator. The steering committee first committed to a safe-ride program to address impaired driving in the community. This intervention, which ran from mid-September 2017 through December 31, 2017, combined $30 coupons for round-trip, ride-sharing arrangements with increased enforcement in high-risk areas and at high-risk times, such as after an Ohio State football game. The coupons were available online as well as at high-risk drinking areas. In addition, the program was promoted significantly on television and radio. External program evaluation included two waves of an intercept survey that would identify the type of people who would usually spend time in hospitality zones; a survey of safe-ride users over five weekends; and usage data from Lyft, one of the ride-sharing participants. The evaluation also included some cost–benefit analyses.

The following are preliminary findings from this intervention: Coupon redeemers said they were less likely to drive while intoxicated but were also likely to have one additional drink before they used the coupon. The analysis suggested that the benefit-to-cost ratio was low. Goldberg noted that although the results were mixed, they created an opportunity for the community to reflect on what the findings mean. To facilitate such reflection, the foundation is convening a community gathering to explore lessons from the program. The gathering will also provide a platform to discuss potentially redesigning the safe-ride program to better address both short-term injury prevention associated with impaired driving and long-term health promotion through reducing heavy drinking. In closing, Goldberg noted that the six pilot cities are testing a diverse set of inter-

ventions that include screening, enforcement, and policy changes. The foundation looks forward to sharing what works—and what does not—to inform best practices in public health.

THE EFFECT OF TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS ON THE HEALTH OF URBAN POPULATIONS: EVIDENCE FROM LATIN AMERICA

Latin America, Olga Sarmiento (University of Los Andes) said, is highly urbanized: More than 80 percent of the population lives in urban areas, and the region includes 19 of the 30 most unequal cities in the world. About 36 percent of the region’s large cities exceed WHO air-quality guidelines, and 5 of the 20 most congested cities in the world are in Latin America, she noted. At the same time, she said, many cities in Latin America have developed and embraced innovative transportation policies and interventions that move beyond those of traditional systems.

For example, 55 cities in 13 Latin American countries have bus rapid-transit systems that provide lanes exclusively for buses, and they account for 32 percent of the 171 cities in 42 countries worldwide that have bus rapid-transit systems. In addition, 8 cities in 4 countries have cable-car systems. Nearly 250 cities have ciclovias recreativas, which are open-street programs in which streets are closed to cars at least twice monthly to provide space for biking and other leisure activities. In addition, 51 cities in 10 countries have established nearly 3,500 kilometers of infrastructure for cycling—largely through PPPs and with support from local communities.

Bogotá, Colombia, hosts one of the largest bus rapid-transit systems. TransMilenio SA, which accounts for 18 percent of all trips taken in the city on any given day, is run by a public entity, but the bus operators and fare collection company are all private. All told, Sarmiento said, 45 percent of individual trips in the city are made by public transport and account for 2.4 million passengers per day. Despite the city’s congestion, the average speed of the TransMilenio buses is 26 kilometers per hour, which makes it the fastest mode of transportation in Bogotá. A survey of 1,000 adults found that TransMilenio users were more likely to meet physical activity recommendations and were more likely to engage in moderate to vigorous activities compared to those who were not users of the system (Lemoine et al., 2016b). However, TransMilenio users have noted that the system is very congested, and air quality on the buses could be better.

Currently, Bogotá is working on expanding TransMilenio, and Sarmiento and her colleagues have used an agent-based model to assess how system expansion would affect walking behavior. This model suggests that walking minutes will increase to a threshold but will decrease thereafter (Lemoine et al., 2016a). The threshold, she said, depends on what other modes of transportation are available and how far apart the

boarding stations are located. In Bogotá, stations are about 680 meters apart. She explained, “Our recommendation for the city of Bogotá is to keep having those stations at least 600 meters apart if one of the effects for TransMilenio is related to healthy behaviors, which, in this case, is walking.”

Sarmiento and her collaborators have also evaluated connections between mental health and the availability of good public transportation systems. In one study of 11 Latin American cities, her team found that longer, more delayed commutes were associated with more depressive symptoms. However, there was an exception: Individuals who had a transit stop within a 10-minute walk were less likely to have depressive symptoms. In addition, users of urban transit systems were nearly 5 percent less likely than drivers to screen positively for depression (Wang et al., 2019).

In 2018, Bogotá opened a new transportation system, the TransMiCable cable-car operation, that is also a PPP. Currently, 21,000 people use the 3.43 kilometer system daily to commute from some of the poorest areas in the city. The system has reduced travel time from 62 minutes to 13 minutes from the informal settlements it serves into the city. It has also stimulated 16 different projects that are bringing parks, a library, an administrative office, a museum, and other improvements to this part of the city. Sarmiento’s team is now evaluating how TransMiCable has affected the amount of exercise cable-system riders get and the levels of air pollution to which they are exposed during commutes.

DISCUSSION

Rebecca Martin, moderator, started the discussion by asking panelists how they share their evaluation results. Goldberg said her program has an evaluation team that attends steering committee meetings to explain the results of their evaluations and to provide context for how those results fit into a larger knowledge base. Her program is also preparing to launch a website where data will be available for research purposes. Sarmiento said her team shares its results with city administrators and transit-system operators.

Dietz then responded to a question about whether to start addressing obesity by reducing consumption of ultra-processed foods in countries that have only recently been exposed to them. Dietz replied that more working experience is needed in low- and middle-income countries and that data need to be shared with policy makers there. In his opinion, most health systems in these countries are clearly not prepared for the consequences of increasing obesity—particularly type 2 diabetes and its medical complications. He said Latin America is an exception, and it is

“probably the most progressive place in the world where governments are addressing the epidemic of obesity.” He also noted that obesity is not necessarily considered negative; in some countries, such as South Africa, increased body size is considered an indication that a person is HIV negative.

Responding to a question about what communication tactics the panelists use to reach their target audiences, Goldberg said her organization’s programs use social marketing approaches, community ambassadors, and broader communication channels to create a culture where harmful drinking is unacceptable. She noted that the alcohol industry can be a valuable partner because of its expertise in reaching specific audiences with various communication and marketing strategies.