3

Regulatory Framework for Compounded Preparations

Compounded drugs have long been part of the medical armamentarium. Through drug compounding, compounders may offer therapeutic alternatives for patients with unique medical needs that cannot be met by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug products (FDA, 2017a). The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) of 1938 is the primary source of FDA’s authority over prescription drugs. To help protect the public from ineffective or potentially dangerous products, prescription drug manufacturers have been required to submit evidence of the safety of drugs since 1938, and of their efficacy since 1962, before they can be sold in the United States (Kim, 2017).1 Although compounded drugs require a prescription prior to being dispensed to patients, the FDCA does not give FDA similar authority to evaluate their safety, effectiveness, or quality before they are marketed (FDA, 2017a). In the absence of substantial federal oversight, states remain the primary regulators for the majority of prescription-based drug compounding practices (Kim, 2017).

This two-tiered system of regulatory oversight of the U.S. drug market—in which FDA primarily oversees the production of manufactured drugs and states primarily oversee compounded drugs (Kim, 2017)—is the subject of this chapter. It begins with a comparison of the federal regulatory structures for manufacturer-distributed drugs versus

___________________

1 P.L. 87-781, 76 Stat. 780 (1962) (current version as amended at 21 U.S.C. §§ 301–392).

compounded drugs, and then it reviews key regulatory issues related to the U.S. compounded drug market.2

FDA-APPROVED DRUG PRODUCTS

FDA approves a new drug for public use only after careful review of data from preclinical studies in animals and human clinical trials that determine whether the benefits of the drug outweigh its known and potential risks. FDA’s direct involvement begins after the drug sponsor has gathered sufficient preclinical information to warrant testing in humans; this information includes the drug’s chemical and physical properties; biochemical properties, such as solubility; metabolism; and factors influencing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drug (FDA, 2016a, 2020b).

At that point, and before beginning clinical testing, the drug sponsor must submit the results of its preclinical testing to FDA in an investigational new drug (IND) application. The IND application, in addition to plans for human clinical trials, also includes information about the proposed manufacturing process to ensure that the company can produce consistent batches of the drug. Human trials can start 30 days after submission of the IND, allowing FDA time to review the information to ensure that participants will not be exposed to undue risk (FDA, 2020b).3

Drugs covered by an IND generally undergo a multistage process of human clinical testing. The first phase of clinical trials is designed to assess how the drug is metabolized and excreted; to identify the most frequent, acute safety issues; and to evaluate different dosing levels, usually in a small number of healthy volunteers.4 Phase 2 trials gather initial data about drug activity (often as measured by surrogate endpoints, such as changes in biomarkers) and adverse effects in a larger number of individuals who have the condition or disease the product is intended to treat. These trials may continue to evaluate a range of doses to determine the optimal dose with respect to both efficacy and safety.

Phase 3 trials are typically randomized controlled trials that compare the safety and efficacy of the drug with a placebo or another product approved for the proposed indication. These trials may also study different populations and different dosages of the drug; in some cases, the drug may

___________________

2 Several of the hormones covered in this report can be purchased online and in health stores as dietary supplements, including in doses and combinations similar to those available through compounded formulations. However, dietary supplements fall under a different regulatory structure than compounded drugs, and thus will not be discussed in detail in this chapter.

3 FDA can issue a clinical hold within these 30 days if it feels the data do not yet support safe study of the drug in humans, or if clarifications are needed to provide the needed assurance.

4 Toxic, high-risk drugs are studied only in populations with the disease or condition to be treated rather than healthy volunteers.

be studied in combination with other approved drugs to see if the combination improves outcomes. Phase 3 studies vary in size, depending on the size of the target population and the size of the effect of interest; some phase 3 studies are small, while others recruit thousands of research participants. Phase 3 trials are intended to provide the primary clinical evidence of the safety and effectiveness of the drug (FDA, 2016a). Throughout all phases of testing, study protocols are reviewed by FDA and must receive institutional review board approval (FDA, 2020b).

Depending on the results of the clinical trials, the sponsor (nearly always a pharmaceutical company) may file a new drug application (NDA) proposing that FDA approve a new product for marketing in the United States.5 The NDA includes information about the results of relevant animal studies, results of all clinical studies, and information about the manufacturing, processing, packaging, and investigators conducting the research, as well as proposed labeling language that describes appropriate usage and potential adverse events. FDA reviews the information to determine the following:

- Whether the studies demonstrate that the drug is safe for its intended use and supported by substantial evidence of effectiveness, and whether the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks;

- The appropriateness of the manufacturer’s proposed labeling, including package insert; and

- The adequacy of the manufacturing process and the controls used to maintain the drug’s quality (FDA, 2019e).

After FDA approves a drug, further safety monitoring (phase 4 of the process) is critical because the clinical trials that support approval cannot predict all of a drug’s effects until it is used more broadly. Manufacturers of approved drugs are required to submit regular safety updates to FDA, including results of further studies and adverse event reports they receive

___________________

5 In addition to NDAs, there are other types of therapeutic drug applications. These include a Biologics License Application (used to approve biologics), an Abbreviated Biologics License Application (used to approve biosimilar versions of biologic drugs), and an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) (used to approve generic drugs). Approval of an ANDA requires demonstrating that the generic drug is pharmaceutically equivalent (including having the same dose of active ingredient and method of administration) and bioequivalent (including having the same pharmacodynamic properties, such as maximum serum concentration and time to achieve maximum concentration) to the original version. By meeting these requirements, generic manufacturers do not have to repeat the same battery of clinical trials for their products that led to the approval of the brand-name products serving as the reference products. For additional information, see https://www.fda.gov/drugs/how-drugs-are-developedand-approved/types-applications (accessed May 23, 2020).

from physicians and patients.6 FDA also collects reports of adverse events submitted directly by health professionals and patients and maintains the Sentinel System. The Sentinel System, which launched in February 2016, allows FDA to query large electronic databases of health outcomes derived largely from administrative and claims data from health insurers to identify safety signals or follow up on ones that emerge through postmarket safety reports (FDA, 2019b).

FEDERAL REGULATION OF DRUG COMPOUNDING

Throughout its history, compounding has been considered part of the practice of pharmacy. Because states are the primary regulators of various health care professions, including pharmacy and medicine, compounding is largely regulated at the state level (Glassgold, 2013). Policy makers and federal regulators generally avoided seeking to exercise authority over compounding pharmacy practice given its small scale and the individualized nature of the treatment (Kim, 2017). By the late 1980s, however, compounding had grown into a major industry. As part of an emerging wellness movement, some pharmacists advertised compounded preparations as all-natural and lower risk alternatives to FDA-approved drug products (Boodoo, 2010). In addition, certain large-scale compounding facilities began producing copies of FDA-approved drugs and marketing those products widely across state lines (Glassgold, 2013). These facilities seemed indistinguishable from traditional pharmaceutical manufacturers, except that they did not manufacture drugs in accordance with required quality standards or obtain approval from FDA (Boodoo, 2010). They would obtain state licenses as pharmacies to avoid registering with FDA as a drug manufacturer, but would deliver drugs without having patient-specific prescriptions (Snow, 2013), and in certain instances, used unapproved or withdrawn active ingredients (Kim, 2017). FDA and Congress began to address these issues through the development of guidelines and legislation.

Under the FDCA, compounded drugs are technically considered “new drugs” and thus subject to all of the law’s requirements. However, since it would be impractical for pharmacists to obtain approval for each compounded drug produced to meet the specific needs of an individual patient, FDA generally did not enforce new drug approval requirements for compounded drugs.7

___________________

6 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

7Thompson v. W. States Med. Ctr., 535 U.S. 357, 369–370 (2002) (“[I]t would not make sense to require compounded drugs created to meet the unique needs of individual patients to undergo the testing required for the new drug approval process.”).

To clarify the agency’s role in regulating drug preparations from compounding pharmacies, FDA issued a Compliance Policy Guide (CPG) in 1992.8 The 1992 CPG listed nine actions or factors that might lead FDA to subject a compounder to FDA oversight as a manufacturer, including production of “inordinate amounts” of drugs, using ingredients not from FDA-approved facilities, compounding existing FDA-approved products, and “soliciting business to compound specific drugs” (Kim, 2017; Snow, 2013).9 Despite a ruling in FDA’s favor from a federal court of appeals, FDA still generally did not enforce the CPG in the face of substantial criticism from the pharmacy community (Boodoo, 2010; Snow, 2013). However, in 1997 much of the CPG was incorporated into law as part of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA), and the Section 503A in the FDCA was created. This new section outlined the conditions that compounded drugs must meet to be exempt from certain aspects of the FDCA.10 In addition, Section 503A(c) of the new law prohibited compounding pharmacies from soliciting prescriptions (Snow, 2013).11

In 2001, a group of pharmacies challenged Section 503A(c), arguing that using advertising as a criterion in determining whether to regulate compounding in the same manner as drug manufacturing violated compounders’ commercial speech rights under the First Amendment (Kim, 2017). The Ninth Circuit agreed and invalidated all of Section 503A because of this problematic part. In 2002, the Supreme Court affirmed the Ninth Circuit’s holding that Section 503A(c)’s effect on advertising was unconstitutional.12 However, the Supreme Court did not comment on whether Section 503A’s advertising restrictions were severable from the other provisions of Section 503A, so in the Ninth Circuit, all of Section 503A was considered invalid. This, in effect, eliminated FDA’s ability to regulate compounding in the Ninth Circuit (Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) (GAO, 2016; Kim, 2017).

FDA understood the Supreme Court’s ruling to mean all of Section 503A was invalid nationwide,13 and therefore released an updated, non-legally binding CPG in 2002. Similar to the 1992 CPG, the new guidance document reiterated the criteria FDA would use to determine if actions were

___________________

8 U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Compliance Policy Guide 7132.16, Manufacture, Distribution and Promotion of Adulterated, Misbranded, or Unapproved New Drugs for Human Use by State-Licensed Pharmacies, March 16, 1992.

9Thompson v. W. States Med. Ctr., 535 U.S. (2002).

10 Examples of the outlined conditions are described in later sections of the chapter.

11 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

12 See Thompson v. W. States Med. Ctr., 535 U.S. (2002) and W. States Med. Ctr. v. Shalala, 238 F.3d 1090, 1092 (9th Cir. 2001) for additional details.

13 Pharmacy Compounding Compliance Policy Guide; availability. 67 FR 39409 (June 7, 2002).

legitimate compounding or manufacturing subject to FDA oversight, while excluding any restrictions on promoting compounding services (GAO, 2013; Nolan, 2013; Snow, 2013).14 In 2008, FDA regulation of compounding became more complex when the Fifth Circuit, in Medical Center Pharmacy v. Mukasey, concluded that Section 503A(c) was severable.15

In October 2012, contaminated injections from the New England Compounding Center (NECC), a large-scale drug compounding facility, led to a fungal meningitis outbreak that killed more than 60 people and injured more than 700 (FDA, 2017a). This outbreak of fungal meningitis brought national attention to the incomplete oversight of compounding. As early as 2002, FDA suspected that NECC likely used illegitimate compounding practices, and FDA had inspected NECC three times by 2004 (Kim, 2017). FDA sent a warning letter to NECC in 2006 asking the company to make its manufacturing practices safer (U.S. House of Representatives, 2013). However, FDA never required correction of NECC’s problematic compounding practices (Kim, 2017). When FDA officials inspected the NECC plant in the aftermath of the outbreak, they found vials of steroids filled with enough floating contamination to be visible to the human eye (Grady et al., 2012). Partly as a result of this incident, Congress passed the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA) in November 2013 to clarify FDA’s authority in regulating and overseeing compounded drugs.

Drug Quality and Security Act

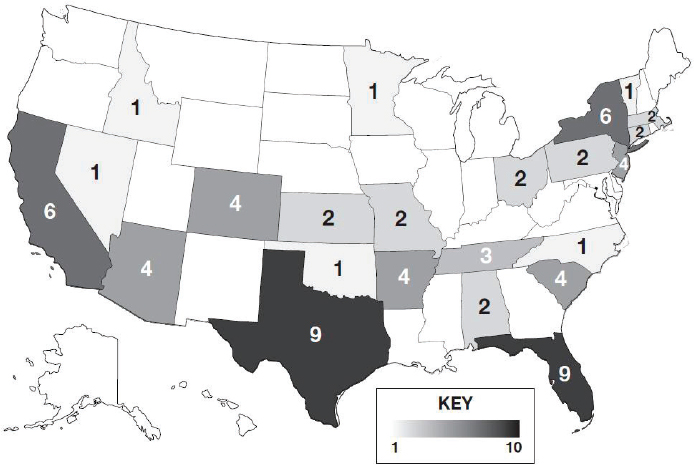

Title I of the DQSA, called the Compounding Quality Act, amended Section 503A to remove the restrictions on soliciting prescriptions, and added the new Section 503B to the FDCA, creating a second category of drug compounding with increased federal regulatory oversight.16 Section 503B established a new category of compounder termed 503B outsourcing facilities that can voluntarily register with FDA to compound without a patient-specific prescription and without restrictions on interstate distribution.17 See Figure 3-1 for a geographic distribution of 503B outsourcing facilities throughout the United States.

503A Compounding Pharmacies

Section 503A exempts drugs that meet certain conditions from three statutory FDCA requirements: new drug approval, labeling with adequate

___________________

14 CPG § 460.200 (May 29, 2002).

15Medical Center Pharmacy v. Mukasey, 536 F.3d 383, 404 (5th Cir. 2008).

16 Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013, P.L. 113-54, 127 Stat. 587 (codified at 21 U.S.C. § 301).

17 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

NOTES: Darker shading reflects a greater number of outsourcing facilities in the state. Values of 503A pharmacies are difficult to estimate owing to a lack of standardized reporting, wide-ranging scopes of compounding between pharmacies, and frequent changes in the number of 503A pharmacies. See Appendix E for additional data on 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities.

SOURCE: FDA, 2020c.

directions for use, and current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) procedures. To be exempt from these requirements, a drug must be compounded by a licensed pharmacist or physician with a valid prescription for an identified patient, or must be compounded in limited quantities in anticipation of a prescription based on a history of prescription orders (often referred to as anticipatory compounding). In addition, if not compounded from an existent FDA-approved drug product, the drug must use bulk drug substances that meet United States Pharmacopeia-National Formulary (USP-NF) standards in applicable monographs, if a monograph exists.18 Section 503A also prohibits compounding drugs that have been withdrawn as a result of safety or effectiveness concerns, present demonstrable difficulties for compounding, are essentially copies of FDA-approved drugs, or compounded within

___________________

18 Other allowable conditions for the use of bulk drug substances in compounded preparations are discussed later in this chapter.

a state that has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding19 with FDA, or within a licensed pharmacy (or by a licensed physician) where the compounded preparations distributed out of state do not exceed 5 percent of total prescriptions dispensed or distributed by that particular pharmacy or physician (Kim, 2017; Snow, 2013).20

Compounding pharmacies that qualify for Section 503A exemptions are not required to register with FDA, and FDA neither routinely inspects compounding pharmacies nor assesses the quality of the compounded preparations produced by those pharmacies (Gudeman et al., 2013). Rather, state boards of pharmacy are the primary overseers of Section 503A compounding pharmacies, leading to less consistent and comprehensive supervision than would be given by FDA and state-by-state variability in the degree of oversight (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016). While gaps in oversight exist, a violation of 503A, or other applicable statutes within the FDCA, may result in warning letters, product seizures, injunctions, or prosecution by state or federal authorities (FDA, 2016b).

503B Outsourcing Facilities

In addition to amending Section 503A, the DQSA added Section 503B to the FDCA, establishing outsourcing facilities, which are operations that can compound without the need for patient-specific prescriptions, though they may also compound for patient-specific prescriptions. Section 503B describes the conditions that must be satisfied for drugs compounded by or under the direct supervision of a licensed pharmacist in an outsourcing facility to qualify for exemptions from FDCA requirements for new drug approval, labeling, and drug supply chain security. Similar to 503A pharmacies, 503B facilities are restricted from compounding drugs that have been withdrawn from the market because of safety or effectiveness concerns, present demonstrable difficulties for compounding, or are essentially copies of FDA-approved drugs. Section 503B also describes separate restrictions on the use of bulk drug substances.21 Under Section 503B, compounded drugs from outsourcing facilities are required to provide some labeling, though FDA does not review these labels for approval, and the required information for the label is minimal.22 See sections below for an additional discussion on requirements for labels.

___________________

19 A standard Memorandum of Understanding has not yet been finalized. A draft form of the agreement, published in 2018, can be found at https://www.fda.gov/media/91085/download (accessed April 13, 2020).

20 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

21 The separate restrictions for producing copies of FDA-approved drug products and using bulk drug substances are described later in this chapter.

22 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

Outsourcing facilities are required to register annually with FDA, undergo inspections according to a risk-based schedule, and report adverse events. Outsourcing facilities must submit a biannual report to FDA identifying the compounded drugs they prepared in the past 6 months.23 Section 503B facilities must also comply with CGMP requirements,24 which requires additional investments in time and resources compared to those required of most 503A compounding pharmacy operations. Section 503B facilities thus have more federal oversight to ensure drug quality than do 503A compounding pharmacies.

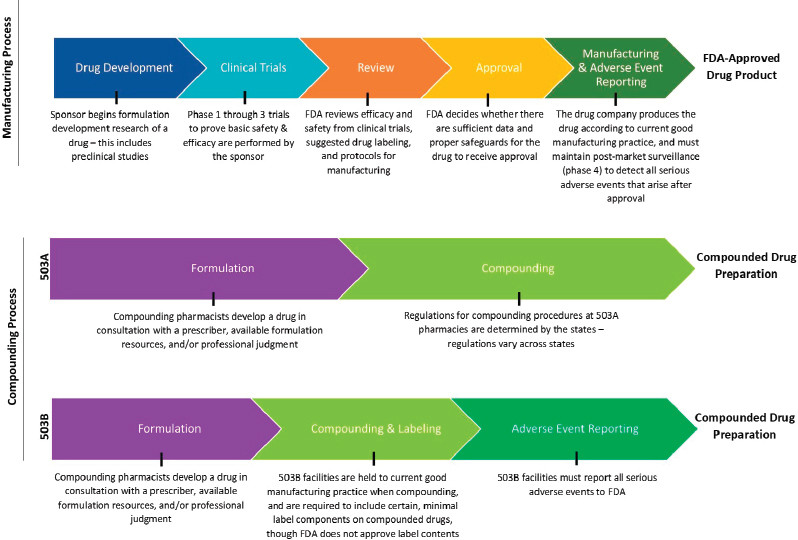

In summary, federal oversight of the manufacturing process for FDA-approved medications and non-FDA-approved compounded medications is complex. See Figure 3-2 for a distilled graphic depiction of select steps in FDA’s oversight of these processes.

Distinguishing Features of 503A and 503B Compounders

Section 503A compounders and Section 503B outsourcing facilities have other important differences. Select examples, including those related to the raw materials they can use, their ability to produce copies of FDA-approved drugs, their labeling requirements, and their ability to sell compounded preparations through interstate commerce, are discussed in the sections below. (To review additional key differences, not discussed in this section, see FDA, 2018b.)

Bulk Drug Substances

Sections 503A and 503B place limits on the bulk drug substances, or active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), that can be used in compounded drugs. The FDCA states that 503A pharmacies may only use bulk drug substances that (1) comply with an applicable USP or NF monograph and the USP chapter on pharmacy compounding; (2) are components of FDA-approved drug products if an applicable USP or NF monograph does not exist; or (3) appear on FDA’s list of bulk drug substances that can be used in compounding.25

In contrast, the FDCA states that 503B facilities may only use bulk drug substances that: (1) are used to compound drug products that appear on FDA’s drug shortage list at the time of compounding, distribution, and

___________________

23 Additionally, outsourcing facility preparation reports can be found at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/information-outsourcing-facilities (accessed April 13, 2020). These preparations are likely less diverse than those that are produced at 503A compounding pharmacies.

24 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

25 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

NOTES: The figure is intended to provide a general overview of the statutory and regulatory processes required of FDA-approved drug products and compounded drug preparations. The figure does not offer a complete summary of the complex regulatory framework for all drug products or compounded preparations. Compounding preparations can be made from either bulk drug substances or FDA-approved drug products that are subsequently modified. 503B outsourcing facilities can make compounded drugs without a patient-specific prescription.

SOURCES: FDA, 2016a; Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act § 503A and § 503B.

dispensing; or (2) appear on FDA’s list of bulk drug substances for which there is a clinical need.26,27

FDA is in the process of compiling 503A and 503B “bulk lists” of allowable bulk drug substances for compounding (FDA, 2019a).28 Drug makers may challenge the nomination of a bulk drug substance to the list during a notice-and-comment period, especially if an FDA-approved drug product already exists to meet the clinical need. However, until these lists are finalized, FDA’s interim policy authorizes facilities to compound using any bulk drug substance that has been nominated to the list with sufficient information for FDA to evaluate the substance and that does not raise significant safety concerns (FDA, 2017b,c).

Copycat Drugs

Both Sections 503A and 503B prohibit the compounding of drugs that are “essentially copies” of FDA-approved drug products. However, what FDA considers a copy differs between the two categories of compounding. Section 503A prohibits compounders from compounding “regularly or in inordinate amounts” drugs that are “essentially copies” of FDA-approved drugs. Under Sections 503A and 503B, drug copies do not include compounded formulations that have been changed in a way that the prescriber determines will provide a significant difference for an identified individual patient compared to a FDA-approved drug product. Unlike Section 503A, Section 503B allows copies of FDA-approved drugs to be compounded if the approved drug is on the drug shortage list.29 The prohibition on compounding copies of FDA-approved drugs ensures that patients do not receive compounded drugs that have not undergone FDA approval when their needs could be met by FDA-approved drugs.

Labeling

Drugs compounded under Sections 503A and 503B are exempt from certain federal labeling requirements. However, Section 503B does require the inclusion of certain label information on compounded drugs, including the statement “this is a compounded drug” (or comparable statements),

___________________

26 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

27 FDA limitations on the bulk drug substances available to outsourcing facilities for compounding are to prevent outsourcing facilities from growing into manufacturing operations that make unapproved drugs (FDA, 2019a).

28 List of Bulk Drug Substances That Can Be Used to Compound Drug Products in Accordance with Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 CFR §§ 216 (February 19, 2019).

29 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

the dosage form and strength, the date the drug was compounded, the expiration date, and storage and handling instructions, among others. If the drug is dispensed or distributed other than for a patient-specific prescription, it must be labeled with the statement “not for resale” or “office use only.” For outsourcing facilities, the container for individually stored units of compounded drugs must include a list of active and inactive ingredients, where to report adverse events, and directions for use (Dabrowska, 2018).30 However, compounded drugs are not required to have labels that mirror FDA-approved versions in the same drug class. For example, if a class of FDA-approved drugs is required to have a boxed warning (the most prominent kind of warning featured on a drug’s labeling), a compounded drug containing an active ingredient in that class is not required to carry the same boxed warning (FDA, 2018b).

Interstate Distribution

Section 503A prohibits compounding pharmacies from distributing compounded drugs outside of the state in quantities that exceed 5 percent of the total prescription orders dispensed or distributed by that pharmacy, unless the state has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with FDA.31 The policy serves to facilitate investigations of complaints related to compounded drugs distributed out of the state where it was compounded, and to prevent inordinate interstate distribution of compounded drugs that is characteristic of drug manufacturing.32,33 The law does not restrict interstate distribution of compounded drugs from 503B outsourcing facilities.

Regulations Related to Marketing: The Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Protection Act

Compounded drugs have been promoted through major marketing campaigns in physician offices and pharmacies, as well as by online advertisements. Some of these promotional campaigns have included unsubstantiated claims of safety, disease prevention, and antiaging properties (Patsner, 2008). While the FDCA gives FDA authority to take enforcement action against compounders who produce misbranded drugs (defined as those that

___________________

30 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

31 See the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act § 503A(b)(3)(B)(i). 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

32 A standard MOU has not yet been finalized. A draft form of the agreement, published in 2018, can be found at https://www.fda.gov/media/91085/download (accessed April 13, 2020).

33 Memorandum of Understanding Addressing Certain Distributions of Compounded Drug Products Between the States and the Food and Drug Administration; Revised Draft; Availability. 83 FR 45631 (September 10, 2018). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-09-10/pdf/2018-19461.pdf (accessed April 13, 2020).

make false or misleading claims),34 oversight of the fairness of commercial advertising of drugs in the United States also falls to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC, 2019). According to FTC’s Deception Policy Statement, an advertisement is considered “deceptive” if it contains a statement, or omits information, that is (1) likely to mislead consumers acting reasonably under the circumstances (e.g., misleading price claims, sales of hazardous products or services without adequate disclosures); and (2) is “material,” meaning it is likely to affect a consumer’s conduct or decision in regard to the product or service (Miller, 1983).

In April 2007, FTC representatives testified to Congress on its actions against sellers falsely promoting compounded bioidentical hormone therapy (cBHT). Specifically, FTC staff searched for online websites claiming that their progesterone preparations were safe and could prevent, treat, or cure serious illnesses, such as cancer and osteoporosis. FTC found 34 websites making such misleading claims and sent warning letters to each seller. FTC has followed up with these companies, identifying 15 that had removed the claims or preparation from their website, and made further enforcement recommendations for those who had not taken corrective action. The testimony also discussed FTC’s close partnership with FDA in addressing misleading claims for cBHT sold online (U.S. Senate, 2007). See Box 3-1 for additional information on FTC standards and practices for deceptive advertising.

In October 2007, FTC filed complaints against seven additional online sellers of cBHT, alleging they sold compounded progesterone preparations based on claims without scientific evidence. According to FTC’s complaints, the respondents claimed their compounded progesterone creams were:

- Effective in preventing, treating, or curing osteoporosis;

- Effective in preventing or reducing the risk of estrogen-induced endometrial (uterine) cancer; and

- Do not increase the user’s risk of developing breast cancer and/or are effective in preventing or reducing the user’s risk of developing breast cancer (FTC, 2007).

Since the complaints were issued, six of the sellers have signed consent orders preventing them from making similar unsubstantiated claims in the future (FTC, 2007).

States also may play a role in combating false and misleading advertisements. Recently, Tennessee prevailed in demonstrating that a compounding pharmacy in the state had violated the Tennessee Consumer Protection Act with its cBHT marketing and advertisements. The final ruling concluded

___________________

34 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act § 505D(c)(1). 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

that the compounding pharmacy had engaged in deceptive advertising by promoting cBHT as absolutely safe and free from side effects, as well as making claims regarding the benefits of cBHT without adequate support. The pharmacy in question was ordered to pay more than $18 million in damages to the consumers who had used its cBHT preparations.35

For consumers to understand the potential risks and benefits of cBHT, it is important that labeling and advertising claims related to compounded drugs be truthful, not misleading, and substantiated with sound evidence. This may be especially true for hormone therapy, since some of the more serious adverse events associated with hormone therapies can take years to

___________________

35 Office of Tennessee Attorney General. 2020. Email from B. Harrell to National Academies staff regarding State of Tennessee v. HRC Medical Centers, Inc. legal decision. April 29, 2020. Available through the National Academies Public Access File.

develop, delaying the realization of the true harm of false and misleading advertising (Cirigliano, 2007).

FTC does not offer specific guidance on advertising compounded drugs. It has, however, issued recommendations for advertising dietary supplements that could aid compounders in the development of advertising material. These recommendations call for:

(1) careful drafting of advertising claims with particular attention to how claims are qualified and what express and implied messages are actually conveyed to consumers; and (2) careful review of the support for a claim to make sure it is scientifically sound, adequate in the context of the surrounding body of evidence, and relevant to the specific product and claim advertised. (FTC, 2001b)

CURRENT CONCERNS WITH FEDERAL REGULATIONS FOR COMPOUNDED DRUGS

Despite the FDAMA’s and the DQSA’s clarification of compounding’s federal regulatory environment, confusion over some aspects of compounding regulation and oversight remain, particularly where both federal and state regulators have overlapping authority.36 These points of unresolved confusion include the registration of outsourcing facilities, prescription requirement, and pharmacy inspections.

Outsourcing Facility Registration

While Section 503B confers the ability to compound without a patient-specific prescription,37 the investment required to comply with CGMP requirements may create incentives for facilities to forego voluntary 503B registration with FDA. Thus, compounding pharmacies that distribute drugs without a prescription do so without the commensurate oversight, instead purporting to operate inappropriately under 503A oversight (FDA, n.d.). The exact number of large-scale pharmacies compounding beyond the scope of 503A is unknown, but as of February 2020, only 73 of the tens of thousands of U.S. compounding facilities were registered as 503B outsourcing facilities (FDA, 2020c).38 In 2016, FDA reported that “in the substantial majority of cases, inspected human drug compounders not registered as outsourcing facilities were compounding at least some of their drugs not in accordance with Section 503A” (FDA, n.d.).

___________________

36 State regulation of drug compounding is discussed later in this chapter.

37 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

38 See Appendix E for additional estimates for 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities.

FDA has declared its intention to pursue 503A pharmacies operating as outsourcing facilities, commenting that it will focus its oversight efforts on 503A pharmacies that are “large-scale, multistate distributors” (Gottlieb, 2018). FDA also declared plans to facilitate compliance with 503B requirements by directing resources toward preoperational inspections and meetings, enhancing postinspection communications, and conducting more regulatory meetings. In addition, FDA plans to implement more flexible, risk-based CGMP requirements that account for the size and scope of an outsourcing facility’s operations as means of lowering the barriers for compounders to register as outsourcing facilities (Gottlieb, 2018). FDA offers in-person and online training geared toward outsourcing facility pharmacists and staff through its Compounding Quality Center of Excellence in an effort to increase understanding of and compliance with the CGMP requirements applied to 503B outsourcing facilities (FDA, 2020a). See Box 3-2 for an additional discussion of concerns regarding large-scale 503A compounding pharmacies.

Prescription Requirement

A second point of controversy is the prescription requirement for 503A compounding pharmacies. The FDCA establishes that producing and distributing compounded drugs without a prescription is only allowed in 503B outsourcing facilities. Section 503A compounding pharmacies, in contrast, require patient-specific prescriptions to dispense compounded drugs.39 However, some state laws, in conflict with federal law, do allow 503A pharmacies to compound “office stock” without a patient-specific prescription (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016).40 Another complicating factor is that in these situations, the compounder and the prescriber of the compounded drugs may be the same individual, setting the stage for a potential conflict of interest not found in the traditional prescription model in which the prescriber and the manufacturer are two different entities.

Certain health care providers have argued for “office use” compounding in 503A pharmacies for health care providers who need compounded drugs for immediate administration (FDA, 2019f). FDA has maintained its position that 503A pharmacies may not compound for office use, stating that pharmacies that need to keep compounded drugs can obtain non-patient-specific compounded drugs from 503B outsourcing facilities (FDA, 2016c). Further complicating the situation, the House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations has indicated that Congress did not intend to prohibit 503A pharmacies from compounding office stock with the passage of the DQSA, requesting that FDA develop guidance on how these pharmacies may continue this practice while complying with federal law.41

Pharmacy Inspections

Inadequate safety inspections remain a third point of contention, particularly related to 503A pharmacies. FDA has the authority to inspect 503A compounding pharmacies, as they are still subject to portions of FDCA regulation, including the prohibition of compounding in insanitary conditions.42 However, 503A compounding pharmacies are not subject to CGMP requirements or routine FDA inspections, even though they represent the majority of compounding facilities in the United States. However,

___________________

39 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

40 Office use refers to non-patient-specific compounding that is for the purpose of providing compounded drugs that can be kept on site by hospitals, clinics, or practitioners and can be used when a patient presents with an immediate need for the drug.

41 U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2016, Report 114-205, 114th Cong., 1st sess., introduced in House July 14, 2015, https://www.congress.gov/congressionalreport/114th-congress/house-report/205 (accessed April 13, 2020).

42 21 U.S.C. § 704(a).

because Section 503A does not require registration with FDA, the agency does not have an inventory of compounders purporting to operate under Section 503A. As a result, FDA often remains unaware of potential issues with compounded drug products or pharmacy facility conditions at 503A pharmacies until it receives a complaint or adverse event report (FDA, 2018c). Based on published calculations, FDA has conducted more than 400 inspections and issued more than 150 warning letters since the enactment of the DQSA (Dabrowska, 2018). See Box 3-3 for a brief discussion of illustrative findings from select compounding pharmacy inspections.

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS OF DRUG COMPOUNDING

There are two primary sources for professional standards of drug compounding: the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and a system of voluntary accreditation.

USP <795>, <797>, <800>

USP is a nonprofit organization that sets standards for the identity, strength, quality, and purity of ingredients used to make drugs. There are three types of compounding standards:

- USP-NF monographs for bulk drug substances and other ingredients used in drugs, both compounded and manufactured, as well as set standards for identity, quality, purity, strength, packaging, and labeling.

- USP compounded preparation monographs provide guidance and set quality standards for the process of preparing compounded formulations (USP, n.d.-b). These preparation monographs include formulas, directions for compounding, beyond-use dates, packaging and storage information, acceptable pH ranges, and stability-indicating assays (USP, n.d.-a). USP currently provides more than 175 compounded preparation monographs (USP, 2019).

- USP also offers eight essential General Chapters that provide overviews of relevant information, procedures, and analytical methods for compounding: USP General Chapters <795>, <797>, <800>, <825>, <1160>, <1163>, <1168>, and <1176> (USP, n.d.-b). Box 3-4 provides more detail about each of those General Chapters.

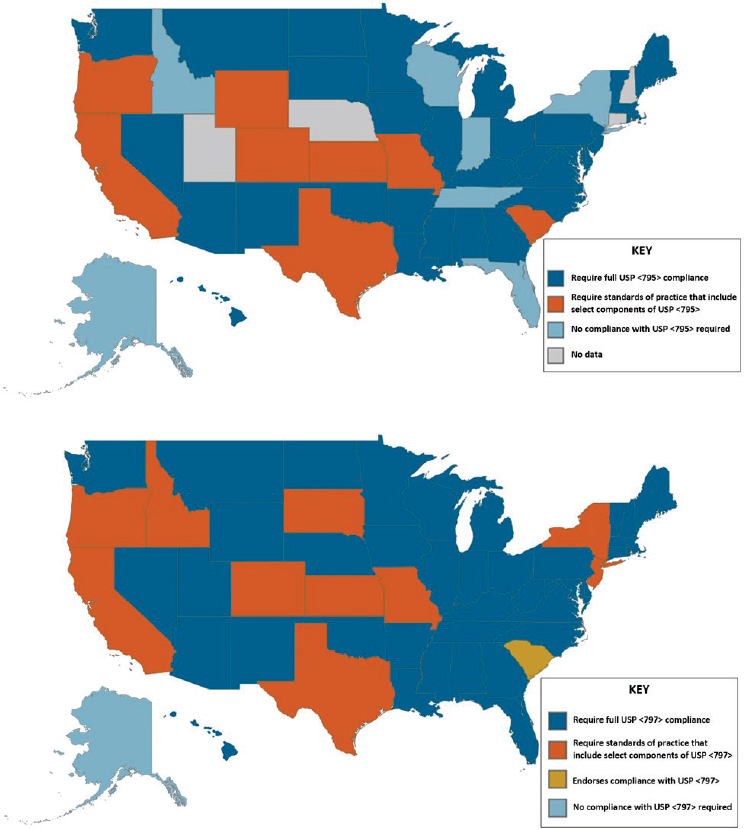

USP itself does not have regulatory or enforcement authority, but certain USP standards are enforceable under state law (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018). USP standards for compounding were first included in the federal law in Section 503A of the FDCA, which states that

“compounders must use bulk drug substances and ingredients that comply with the standards of an applicable USP-NF monograph, if a monograph exists, and the USP chapter on pharmacy compounding.”43 While many states have adopted all or parts of the USP General Chapters on drug compounding, allowing for state regulators and inspectors to enforce these quality standards, compounders in some states are not required to comply with USP compounding standards. Compounding pharmacies in states that have not adapted these chapters, or equivalent standards, are not legally required to compound drugs according to these quality measures (see Figure 3-3).

Some state boards of pharmacy have encountered challenges with enforcing USP chapters, as the language of the chapters is sometimes ambiguous regarding what is required versus recommended. Moreover, the degree of enforcement and oversight will vary from state to state based on the resources, expertise, and capacities of each state’s board of pharmacy (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).

A System of Voluntary Accreditation

Compounding pharmacies can voluntarily request accreditation processes to gain third-party validation that could be an attractive selling point to both prescribers and patients. For instance, the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB), under the Accreditation Commission for Health Care, has established national quality standards for compounding pharmacies based on industry expert consensus (Springer, 2013).44 The accreditation process evaluates compliance with the nonsterile and sterile pharmacy compounding standards outlined in USP <795> and <797>, respectively, for improved quality (ACHC, 2020). According to pharmacy organization representatives, there are nearly 700 PCAB-accredited pharmacies in the United States, and having this accreditation suggests that compounding composes a larger part of the overall business for those pharmacies (NASEM, 2019).45 Similarly, The Joint Commission Medication Compounding Certification program assesses a pharmacy’s compliance with specific standards for preparation and dispensing of sterile and

___________________

43 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

44 PCAB was founded by the following pharmacy organizations: American College of Apothecaries, National Community Pharmacists Association, American Pharmacists Association, National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations, Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, National Home Infusion Association, National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, United States Pharmacopeia (Springer, 2013).

45 Also of note, the nearly 700 PCAB-accredited pharmacies represent only a small proportion of all pharmacies that compound. See Appendix E for additional estimates for 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities.

NOTES: Maps are based on survey data reported by state boards of pharmacy and collected by the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, as well as updates from state boards that had pending legislation at the time of data collection. Idaho Administrative Code, Section 27.01.05.100.05; Illinois Administrative Code, Section 1330.640; Code of Maryland Regulations, Section 10.34.19.02; Pennsylvania Code, Section 49.27.601.

SOURCES: NABP, 2018; The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018.

nonsterile formulations in accordance with USP <795> and <797> (The Joint Commission, 2019). Starting in the fall of 2019, the Board of Pharmacy Specialties began offering an exam for pharmacists to become accredited in Compounded Sterile Preparations, though the specialty has yet to receive official recognition from the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (Board of Pharmacy Specialties, 2020).

STATE REGULATION OF DRUG COMPOUNDING

In the absence of a strong federal regulatory presence, state entities such as state boards of pharmacy have been the primary regulators of drug compounding practices (Staman, 2012). Indeed, in the NECC case, the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Pharmacy (in a joint operation with FDA) had taken action against the facility before the fungal meningitis outbreak, including issuing a cease-and-desist order to NECC for preparing and distributing compounded drugs without a patient-specific prescription (U.S. House of Representatives, 2012). However, state authorities around the country have taken different approaches to the oversight of compounding pharmacies, leading to substantial variation in the level of oversight and frequency of inspections across states.

Even after the DQSA, the majority of compounding pharmacies remain under the oversight of state entities. Outside of high-risk 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities, FDA has maintained that its “aim is to leave the oversight of traditional pharmacy to states” (FDA, 2018a). States face many challenges in regulating and supervising compounding pharmacies, many of which are tied to resource constraints (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).

Inconsistent Oversight

As noted above, state oversight of 503A compounding pharmacies can be inconsistent. In a 2018 survey update of 43 states, 11 (26 percent) reported they do not require compounding pharmacies to have patient-specific prescriptions in advance of compounding. Although the states reportedly place limitations on this practice (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018), the committee has concerns regarding the state-by-state variability in enforcement of these restrictions.

In addition to in-state oversight, state boards of pharmacy also regulate out-of-state pharmacies that ship compounded preparations into their jurisdictions, a process complicated by the variable compounding standards held by individual states. Not only do states have incongruent quality standards for compounding, but states differ in whether they require out-of-state pharmacies to be in compliance with the receiving state’s regulations or those

of the state where the pharmacy is located (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018). This means that preparations compounded under less rigorous standards can still be shipped to a state with more stringent standards.

Similar considerations relate to state inspections. Half of states do not conduct routine inspections of 503A compounding pharmacies, and of those that do, the time between inspections ranges from 1 to 5 years. While best practices recommend that “inspectors of sterile compounding pharmacies should be educated and trained to examine the type of facility they are reviewing,” some states have pharmacy inspectors who are not specially trained to review the practice of compounding (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).

Physician compounding is another area with inconsistent state oversight. Licensed physicians are allowed to compound in a clinical setting under Section 503A,46 yet tracking and oversight of this practice is not as well established as compounding taking place in a pharmacy. Physician compounding is overseen by state boards of medicine, and most states do not have regulations governing this practice (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016).

Efforts have been made to decrease the interstate variability in the oversight of compounding. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) has developed a Multistate Pharmacy Inspection Blueprint Program that provides states with standardized inspection requirements to help ensure consistency in the quality of compounding facilities and processes across states. Currently, 19 states have signed on to this plan (NABP, 2019). FDA has also released a revised draft MOU that will help state regulators to coordinate investigations and corrective actions when compounded medications are shipped across state lines (FDA, 2018f).

Federal–State Coordination

Given the shared federal and state regulatory authority over compounding, some degree of coordination between these levels is to be expected. Section 503B of the FDCA provides FDA with greater oversight of 503B outsourcing facilities than it has for 503A compounding pharmacies. Questions have arisen regarding how state laws or regulations governing compounded drugs should apply when overlap or conflict exists with expanding FDA oversight. Such state compounding laws or regulations could include those regulating sterility testing, adverse event reporting, and compounding for office use (Brown and Tomar, 2016). FDA nominally oversees interstate distribution, but in an effort to increase coordination with the states, FDA has recently awarded a grant to NABP to facilitate information

___________________

46 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

sharing between state regulators and FDA regarding interstate distribution of compounded drugs (HHS, 2019).

Conversely, state laws or regulations might affect a federal compounding regulatory system, as is the case with state regulation of 503B outsourcing facilities. While outsourcing facilities are overseen by FDA, 38 states license or register 503B facilities under various categories, including outsourcing facilities, manufacturers, wholesale distributers, or others.47 Additionally, while federal law does not require outsourcing facilities to obtain a pharmacy license, some states do, while others prohibit pharmacy licensure of 503B facilities. Such overlapping regulatory schemes can be challenging for facilities seeking to register as 503B distributors (The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP, 2018).

It is likely that federal–state coordination in compounding regulation will continue to evolve. FDA has invited states to participate in its inspections and recall discussions and has sought to share inspection and enforcement information with state entities (Gottlieb, 2018).48 The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report in November 2016 on drug compounding that included survey results of state pharmacy regulatory entities. Of 40 states that reported having communications with FDA regarding compounding, 60 percent reported being very or somewhat satisfied with the communication, whereas 23 percent reported being very or somewhat dissatisfied related to delays in response time (GAO, 2016).

FINANCIAL ISSUES AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Development, formulation, and appropriate use of prescription drugs requires participation of many different partners and collaborators, including the patient, physician, pharmacist, and pharmaceutical companies involved in synthesizing active pharmaceutical ingredients and manufacturing

___________________

47 These broad categories likely affect the agreement with the data presented in Figure 3-1.

48 FDA has convened seven intergovernmental meetings with state governments since 2013 (FDA, 2019d).

final products. Each of these roles carries clinical, financial, scientific, ethical, and other responsibilities that may put the physician, pharmacist, or pharmaceutical company executive in conflicting roles or positions.

A conflict of interest exists when professional judgment concerning a primary interest is vulnerable to undue influence by a secondary interest (Thompson, 1993). In the case of the compounded drug market, primary interests include physicians’ ethical (and legal) responsibility to provide evidence-based and patient-centered clinical care and compounders’ similar responsibility to produce high-quality products for their patients. Thus, there is an expectation that ethically practicing physicians will maintain freedom from financial relationships that could compromise patient trust and lead to potentially inappropriate patient care decisions. According to the American College of Physicians Ethics, Professionalism, and Human Rights Committee:

The physician must seek to ensure that the medically appropriate level of care takes primacy over financial considerations imposed by the physician’s own practice, investments, or financial arrangements. Trust in the profession is undermined when there is even the appearance of impropriety. (Snyder, 2012)

Experience in the pharmaceutical industry has shown that financial relationships can exert particularly strong effects on these primary interests. For example, decades of experience have shown that when physicians have financial relationships with pharmaceutical manufacturers, ranging from accepting meals to accepting research support, those physicians were more likely to prescribe or recommend brand-name drugs being sold by those companies rather than lower-cost generic products or other similarly effective alternatives (Fickweiler et al., 2017). Several systematic reviews have also found potential conflicts of interest in the complementary medicine market. These reviews have found that while these complementary medicines lack rigorous efficacy data, and even though pharmacists often feel that they do not have the adequate knowledge to counsel patients on these therapies, pharmacists are encouraged to sell these complementary medicines because of business interests and profits (Boon et al., 2009; Salman Popattia et al., 2018).

Navigating conflicts of interest—particularly financial conflicts—is a special concern in the context of circumstances involving compounded preparations in which regulatory oversight is limited and variably enforced. Financial conflicts that could affect the compounding market may arise when pharmacists or physicians are responsible for care of the patient but also own a financial stake in the compounded preparations they provide. In fact, a 2016 GAO report found that following the passage of the DQSA,

companies were targeting physicians with proposals to establish compounding operations in the physicians’ offices, seeing physician compounding as the best opportunity to increase profits, because physician compounding has less oversight than compounding occurring in a pharmacy (GAO, 2016). Moreover, in the case of cBHT, providers can charge a few thousand dollars or more for these drugs, and may try to justify this cost to patients by citing—without evidence—potential savings on other medications (for high blood pressure, osteoporosis, or depression) or fewer trips to the doctor (Seaborg, 2019). In such cases, it is worth considering to what extent such claims are being driven by the financial conflicts of interest of the provider.

Congress has sought to address financial conflicts of interest through enhanced disclosure. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (PPSA), originally passed in 2010 as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, requires reporting of all payments or gifts of value greater than $10 made to physicians and hospitals by group purchasing organizations and manufacturers of drugs, biologics, and medical devices covered by certain government payers.49 Notably, these financial relationships are also required to be publicly disclosed.50,51 The PPSA, though, does not cover the disclosure of payments and financial relationships between providers and compounding pharmacies or outsourcing facilities.

Individuals with financial stakes in clinics and pharmacies that sell cBHT medications and related services have published peer-reviewed articles on the effects of cBHT. Just as those publishing research about drugs going through the FDA approval process need to disclose involvement with or support from commercial entities, so should those reporting studies of compounded drugs. Researchers’ disclosure of conflicts of interest in published literature would improve transparency in the research and results obtained.

cBHT Formulations

The formulations for cBHT are described in several locations (e.g., USP-NF), including many pharmacies that develop their own formulations. These pharmacy-developed formulations are often marketed to prescribers (Compounding Pharmacy of America, 2020b; Women’s International Pharmacy, 2018). As one study describes, prescriptions were developed based on patient evaluations at the pharmacy with the individualized formulation sent to their doctor for approval (Ruiz et al., 2011). The developer of the

___________________

49 The government payers are Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

50 Social Security Act § 1128G (42 U.S. Code 1320a-7h).

51 Payments are recorded at OpenPaymentsData.CMS.gov (accessed September 9, 2020).

formulation may have a financial holding with a specific formulation, including all excipients, and so may profit from encouraging the use of that formulation.

In addition, anyone may request that an API or excipient have a USP-NF monograph developed. While the sponsor of the request must provide USP with appropriate information and background materials to evaluate the proposed monograph addition (USP, 2016), this action could be perceived as a conflict of interest. As stated in Section 503A of the FDCA, the existence of a USP-NF monograph for a bulk drug substance allows compounders to use that bulk drug substance in compounded preparations under 503A.52 Because USP-NF monographs do not directly address the safety or effectiveness of the bulk drug substance, requests to add new monographs without such data could be seen as a way for the sponsor, and 503A compounders generally, to market new compounded formulations by diversifying the APIs available to them.

Pharmacists undoubtedly have an important role in patients’ use of medications, as supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services advocating for pharmacists’ ability to prescribe certain drugs in urgent situations (Wachino, 2017). However, the potential for conflicts of interest, real or perceived, increases when the pharmacist both predetermines the prescription and sells the preparation.

REFERENCES

ACHC (Accreditation Commission for Health Care). 2020. Compounding pharmacy accreditation. https://www.achc.org/compounding-pharmacy.html (accessed January 4, 2020).

Board of Pharmacy Specialties. 2020. Accreditation. https://www.bpsweb.org/about-bps/accreditation (accessed March 17, 2020).

Boodoo, J. M. 2010. Compounding problems and compounding confusion: Federal regulation of compounded drug products and the FDAMA circuit split. American Journal of Law and Medicine 36(1):220–247.

___________________

52 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 21 U.S. Code Chapter 9.

Boon, H., K. Hirschkorn, G. Griener, and M. Cali. 2009. The ethics of dietary supplements and natural health products in pharmacy practice: A systematic documentary analysis. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Practice 17(1):31–38.

Brown, N. A., and E. Tomar. 2016. Could state regulations be the next frontier in preemption jurisprudence? Drug compounding as a case study. Food and Drug Law Journal 71(2):271–299.

Cirigliano, M. 2007. Bioidentical hormone therapy: A review of the evidence. Journal of Women’s Health 16(5):600–631.

Compounding Pharmacy of America. 2020a. About us. https://compoundingrxusa.com/about-us (accessed January 4, 2020).

Compounding Pharmacy of America. 2020b. Hormone prescription female order form. https://compoundingrxusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/CompoundingPharmacyofAmerica_FemalePerformanceBHRT_2019.pdf (accessed January 4, 2020).

Dabrowska, A. 2018. Drug compounding: FDA authority and possible issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45069.pdf (accessed June 9, 2020).

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2016a. FDA drug approval process. https://www.fda.gov/media/82381/download (accessed June 9, 2020).

FDA. 2016b. Pharmacy compounding of human drug products under Section 503a of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act guidance. https://www.fda.gov/media/94393/download (accessed May 31, 2020).

FDA. 2016c. Prescription requirement under Section 503a of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/97347/download (accessed May 31, 2020).

FDA. 2017a. FDA’s human drug compounding progress report: Three years after enactment of the Drug Quality and Security Act. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

FDA. 2017b. Interim policy on compounding using bulk drug substances under Section 503a of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/94398/download (accessed May 31, 2020).

FDA. 2017c. Interim policy on compounding using bulk drug substances under Section 503b of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/94402/download (accessed May 31, 2020).

FDA. 2018a. 2018 compounding policy priorities plan. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/2018-compounding-policy-priorities-plan (accessed January 4, 2020).

FDA. 2018b. FD&C Act provisions that apply to human drug compounding. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fdc-act-provisions-apply-human-drug-compounding (accessed March 18, 2020).

FDA. 2018c. Insanitary conditions at compounding facilities: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/124948/download (accessed May 31, 2020).

FDA. 2018d. Inspectional observations. https://www.fda.gov/media/112693/download (accessed March 17, 2020).

FDA. 2018e. Inspectional observations. https://www.fda.gov/media/116527/download (accessed March 17, 2020).

FDA. 2018f. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on new steps to help ensure the quality of and preserve access to compounded drugs by pursuing closer collaboration with states. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-steps-help-ensure-quality-and-preserve-access (accessed March 17, 2020).

FDA. 2019a. Evaluation of bulk drug substances nominated for use in compounding under Section 503b of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/121315/download (accessed May 31, 2020).

FDA. 2019b. FDA’s sentinel initiative. https://www.fda.gov/safety/fdas-sentinel-initiative (accessed January 4, 2020).

FDA. 2019c. Inspectional observations. https://www.fda.gov/media/124950/download (accessed March 17, 2020).

FDA. 2019d. Intergovernmental working meeting on drug compounding, September 25–26, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/intergovernmental-working-meeting-drug-compounding-september-25-26-2018 (accessed March 27, 2020).

FDA. 2019e. New drug application (NDA). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/types-applications/new-drug-application-nda (accessed January 4, 2020).

FDA. 2019f. Public meeting: Drugs compounded for office stock by outsourcing facilities. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/public-meeting-drugs-compounded-office-stock-outsourcing-facilities (accessed March 17, 2020).

FDA. 2020a. Compounding quality center of excellence. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/humandrug-compounding/compounding-quality-center-excellence (accessed January 4, 2020).

FDA. 2020b. Investigational new drug (IND) application. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/types-applications/investigational-new-drug-ind-application (accessed January 4, 2020).

FDA. 2020c. Registered outsourcing facilities. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drugcompounding/registered-outsourcing-facilities (accessed January 4, 2020).

FDA. n.d. Notice. https://www.fda.gov/media/98911/download (accessed May 7, 2020).

Fickweiler, F., W. Fickweiler, and E. Urbach. 2017. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: A systematic review. BMJ Open 7(9):e016408.

FTC (Federal Trade Commission). 2001a. Advertising FAQs: A guide for small business. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/advertising-faqs-guide-small-business (accessed June 9, 2020).

FTC. 2001b. Dietary supplements: An advertising guide for industry. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/plain-language/bus09-dietary-supplements-advertising-guide-industry.pdf (accessed June 9, 2020).

FTC. 2006. Federal Trade Commission Act. Incorporating U.S. SAFE WEB Act Amendments of 2006. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/statutes/federal-trade-commission-act/ftc_act_incorporatingus_safe_web_act.pdf (accessed May 4, 2020).

FTC. 2007. FTC charges seven online sellers of alternative hormone replacement therapy with failing to substantiate products health claims. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2007/10/ftc-charges-seven-online-sellers-alternative-hormone-replacement (accessed June 9, 2020).

FTC. 2019. A brief overview of the Federal Trade Commission’s investigative, law enforcement, and rulemaking authority. https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/what-we-do/enforcement-authority (accessed March 18, 2020).

FTC. n.d. Truth in advertising. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/media-resources/truth-advertising (accessed January 4, 2020).

GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2013. Drug compounding: Clear authority and more reliable data needed to strengthen FDA oversight. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-702 (accessed June 10, 2020).

GAO. 2016. Drug compounding: FDA has taken steps to implement compounding law, but some states and stakeholders reported challenges. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681096.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

Glassgold, J. 2013. Compounded drugs. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43082.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

Gottlieb, S. 2018. Examining implementation of the Compounding Quality Act. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressional-testimony/examining-implementation-compounding-quality-act-01292018-01292018 (accessed March 17, 2020).

Grady, D., S. Tavernise, and A. Pollack. 2012. In a drug linked to a deadly meningitis outbreak, a question of oversight. The New York Times, October 4.

Gudeman, J., M. Jozwiakowski, J. Chollet, and M. Randell. 2013. Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs in R&D 13(1):1–8.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2019. Information sharing system for state-regulated drug compounding activities (u01) clinical trial not allowed. Original edition, RFA-FD-19-025. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Kim, S. 2017. The Drug Quality and Security Act of 2013: Compounding consistently. Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 19(2).

Miller, J. I. 1983. FTC policy statement on deception. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission.

NABP (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy). 2018. Survey of pharmacy law. Mount Prospect, IL: National Association of Boards of Pharmacy.

NABP. 2019. Multistate pharmacy inspection blueprint program. https://nabp.pharmacy/member-services/inspection-tools-services/multistate-pharmacy-inspection-blueprint-program (accessed December 23, 2019).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Presentation to the Committee during the open session of Meeting Six. November 12, 2019 (available through the National Academies Public Access File).

Nolan, A. 2013. Federal authority to regulate the compounding of human drugs. Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43038.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

Patsner, B. 2008. Pharmacy compounding of bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (BHRT): A proposed new approach to justify FDA regulation of these prescription drugs. Food and Drug Law Journal 63(2):459–491.

Ruiz, A. D., K. R. Daniels, J. C. Barner, J. J. Carson, and C. R. Frei. 2011. Effectiveness of compounded bioidentical hormone replacement therapy: An observational cohort study. BMC Women’s Health 11:27.

Salman Popattia, A., S. Winch, and A. La Caze. 2018. Ethical responsibilities of pharmacists when selling complementary medicines: A systematic review. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 26(2):93–103.

Seaborg, E. 2019. Targeting patients with patients with pellets: A look at bioidentical hormones. https://endocrinenews.endocrine.org/targeting-patients-with-pellets-a-look-at-biodentical-hormones (accessed March 18, 2020).

Snow, M. 2013. Seeing through the murky vial: Does the FDA have the authority to stop compounding pharmacies from pirate manufacturing? Vanderbilt Law Review 66(5):1609–1639.

Snyder, L. 2012. American College of Physicians ethics manual: Sixth edition. Annals of Internal Medicine 156(1 Pt 2):73–104.

Springer, R. 2013. Compounding pharmacies: Friend or foe. Plastic Surgical Nursing 33(1):24–28.

Staman, J. 2012. FDA’s authority to regulate drug compounding: A legal analysis. Congressional Research Service. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20121017_R40503_5db0387896095562fa83651736b4fc3a2901a2e7.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

The Joint Commission. 2019. Medication compounding certification. https://www.jointcommission.org/certification/medication_compounding.aspx (accessed March 17, 2020).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2016. National assessment of state oversight of sterile drug compounding. Philadelphia, PA: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

The Pew Charitable Trusts and NABP (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy). 2018. State oversight of drug compounding. Major progress since 2015, but opportunities remain to better protect patients. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2018/02/state-oversight-of-drug-compounding (accessed February 5, 2020).

Thompson, D. F. 1993. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. New England Journal of Medicine 329(8):573–576.

University Compounding Pharmacy. 2020. Areas we serve. https://univrx.com/areas-we-serve (accessed January 4, 2020).

U.S. House of Representatives, 112th Congress Committee on Energy and Commerce. 2012. The fungal meningitis outbreak: Could it have been prevented? https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-112hhrg88248/html/CHRG-112hhrg88248.htm (accessed May 31, 2020).

U.S. House of Representatives, 113th Congress Committee on Energy and Commerce. 2013. FDA’s oversight of NECC and ameridose: A history of missed opportunities? https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF02/20130416/100668/HHRG-113-IF02-20130416-SD101.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

U.S. Senate 110th Congress Special Commitee on Aging. 2007. Bioidentical hormones: Sound science or bad medicine? https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110shrg37150/html/CHRG-110shrg37150.htm (accessed May 31, 2020).

USP (United States Pharmacopeia). 2016. USP guideline for submitting requests for revision to USP–NF: General information for all submissions. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/get-involved/submission-guidelines/general-information-for-all-submissions.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

USP. 2019. Approved USP compounded monographs. https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/get-involved/partner/2019-02-approved-usp-compounded-monographs.pdf (accessed March 17, 2020).

USP. n.d.-a. Compounded preparations monographs (CPMs). https://www.usp.org/compounding/compounded-preparation-monographs (accessed March 17, 2020).

USP. n.d.-b. USP compounding standards. https://www.usp.org/compounding-standards-overview (accessed January 4, 2020).

Wachino, V. 2017. State flexibility to facilitate timely access to drug therapy by expanding the scope of pharmacy practice using collaborative practice agreements, standing orders or other predetermined protocols. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib011717.pdf (accessed June 10, 2020).

Women’s International Pharmacy. 2020. Areas we serve. https://www.womensinternational.com/areas-we-serve (accessed January 4, 2020).