2

To Thrive in Middle School and Beyond, and the Middle School Years, a 360 View

The first of three panel sessions focused on an overview of the developmental needs, considerations, and issues related to middle schoolers. The session was moderated by Michelle Larkin of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and featured presentations by Phyllis Fagell of the Sheridan School, Joanna Williams of the University of Virginia, and Joaquin Tamayo of EducationCounsel. A question-and-answer session with the audience followed.

TO THRIVE IN MIDDLE SCHOOL AND BEYOND

Phyllis Fagell, certified professional school counselor at the Sheridan School in Washington, DC, psychotherapist with The Chrysalis Group, and journalist, delivered the keynote address. She opened by discussing the lack of research focused specifically on middle schoolers. She explained that middle school is a “distinct developmental phase” with specific needs and that research should not classify this group of adolescents with high school students and older teenagers. After researchers initially focused on middle schools in the 1980s and 1990s, interest in middle schools waned. The focus shifted to early childhood development and literacy and the college-to-career transition. Fagell found a lack of information on innovation in school settings within the education and counseling fields and limited resources on how to create effective communication channels between parents, administrators, teachers, and middle school age children. As a counselor and a psychotherapist, she has heard from parents voicing their uncertainty over what roles they

should play in their child’s life at school, what level of independence to give their child, and how they should handle expectations from school administrators. Teachers expressed their frustration at the lack of boundaries demonstrated by parents, while students wanted autonomy. Fagell added that there is no system consistently in place within middle schools to navigate these concerns.

Fagell continued to a discussion on the pertinent characteristics of middle school students. They need strong and appropriate role models to solidify their values and develop academic and life skills (see Box 2-1). One area of concern was mental health: middle schoolers reported increased rates of mental illness. For example, Fagell said that suicide rates have doubled from 2007 to 2014 among students between the ages of 10 and 14. Fagell saw the opportunity to guide students on how to self-regulate emotions and use various tools to navigate such emotions as a prevention strategy. Fagell also asserted that middle schoolers experienced drops in confidence, performance, and academic self-identity. Fagell mentioned a 1968 study (Ainsworth-Land and Jarman, 2000) that disputed the idea that only some people have the trait of creativity. The researchers tested 1,600 5-year-olds on their creativity and retested at 10 and 15 years of age. They also tested almost 300,000 adults. The study found that 98 percent of the 5-year-olds were rated as highly creative, which dropped to 30 and 12 percent when the children reached the ages of 10 and 15, respectively. Two percent of the adults were rated as highly creative. Fagell stated that adults, including parents and school professionals, need to encourage creative behavior in middle schoolers by promoting their ability to be innovative.

As Fagell shared, the middle school stage is one of rapid change and transition. She stated that middle schoolers are establishing their identity as their empathy is developing and bullying is increasing. Factors that influence identity include being exposed to situations that trigger anxiety, emotional contagion, the Internet, negative news, and a divisive political climate. Fagell referenced a study that found that more than 30 percent of adolescent students have been victims of electronic dating aggression and that 45 percent are online “almost constantly” (Cutbush et al., 2010). Fagell noted that adults should listen to middle schoolers about what constitutes salient aspects of their identities instead of imposing ideas on them. She cited another study on creating a secure place to help middle schoolers safely explore their identities (Anderson and Jiang, 2018) and said that one example is the Gay–Straight Alliance (GSA). Over the past several years, Fagell has seen the growth of GSAs in her school system, adding that those involved in GSAs have experienced 20 percent fewer homophobic remarks and are 48 percent less likely to be bullied.

Fagell also mentioned that the school structure and setting may not support children in this developmental stage. She stated that children go from elementary school with one main teacher and the same group of peers to middle school, where they often change classes and teachers.

Fagell shared that general messages surrounding middle school and middle schoolers have often been negative. Many of the false messages that plague middle schoolers are often given to them by adults and popular culture, such as that they are mean or “looking for drama,” closed off and not wanting to share or talk to adults, and trying to be difficult and obstructive. Additionally, Fagell suggested that adults may be projecting their own negative views on this developmental stage, which children may then internalize. Fagell believes that it should be established that although middle schoolers tend to be well meaning, they are lacking in life skills and understanding of others’ intent and meaning, which may lead to anxiety and miscommunication. She believes that adults, including health practitioners, educators, parents, and researchers, can mitigate these challenges by self-identifying as helpers and focusing on the children’s strengths. Fagell said that messages directed to and about middle schoolers may be framed in a more positive light and suggested that adults approach middle schoolers “on their terms.” This includes asking more questions rather than making assumptions about their motivations. Fagell noted that middle schoolers may lack the necessary skills and tools to address their lack of confidence or need for academic support and thus may appear to be difficult or obstructive.

Fagell concluded her address by discussing some of the life skills to develop in middle school to help students succeed both academically and personally (see Box 2-1). She believes that the skill of considering others’

perspectives is important in creating empathy for others and oneself. Middle school students also have less ability to interpret feedback, making learning how to self-regulate emotions a necessity to respond more appropriately to conflict. Fagell mentioned the example of a school principal who used shame to address a situation when a group of students played a practical joke on another student. Fagell pointed out that the manner in which the principal approached the situation was not helpful given that the students did not understand why they had acted that way. To better understand the students, the principal reframed his approach and asked “were you your best selves?” The question then helped the students reconsider their actions and the principal could see that the students had a desire to be good and kind.

THE MIDDLE SCHOOL YEARS, A 360 VIEW1

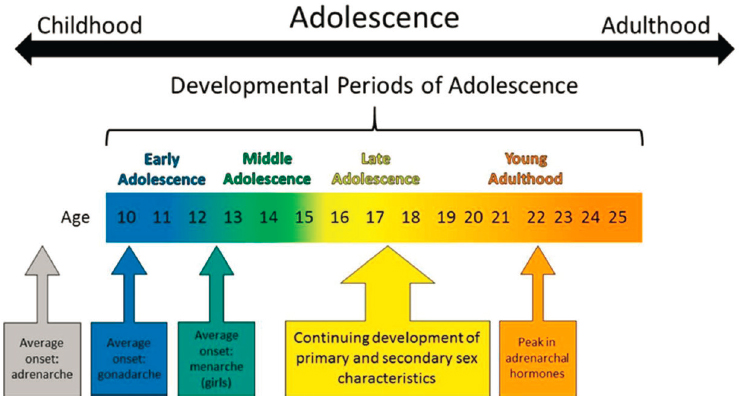

Joanna Williams and Joaquin Tamayo followed the keynote speaker, with Williams speaking first. Williams aimed to give a holistic view of early adolescent development by defining early adolescence, discussing the core physical, neurobiological, and psychosocial processes, and exploring the factors that can compromise and promote development. Williams defined early adolescence as a time between childhood and adulthood in which developmental changes impact growth. She explained that although an exact age range is not available, the agreement is that adolescence begins with the onset of puberty and ends in the mid-20s (see Figure 2-1). Williams’s presentation focused on early adolescence, which lasts through approximately 14 years of age, and added that about 21 million people in the United States are in this age group. The onset of puberty not only acts as a catalyst for physical processes but also promotes interest in intimate relationships and awareness of sexuality. Williams discussed that, as with all developmental stages, biological processes have individual variations, so children are not developing at the same rate. Puberty begins in the limbic regions of the brain, which is associated with sensitivity to reward, social information, threats, and novelty. In early adolescence, these neural connections are particularly strong. Other parts of the brain, such as outer areas and the cortical areas that are responsible for planning, decision making, cognitive control, and self-efficacy, take longer to develop these connections. She noted that early adolescence is associated with increased sensitivity to rewards, risk taking, and an awareness of social relationships and status.

___________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Joanna Williams of the University of Virginia and Joaquin Tamayo of EducationCounsel. The statements made are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCE: Williams presentation, December 5, 2019.

Williams then went on to discuss identity within the context of early adolescence. She said that identity includes questions such as “Who am I?” “How do I see myself?” “Who do I want to be?” and “Where do I fit in?” She found these to be challenging questions because societal and familial expectations might vary from how children want to self-identify. Furthermore, children have distress “when there are contradictions between their ideal versions of themselves versus how they are actually experiencing reality.” Children may demonstrate characteristics that they have identified as being ideal, such as being positive and socially engaged, but may be struggling with other traits, including anxiety or distress.

Williams continued by exploring the factors that compromise and are protective of development. She noted that while early adolescence is a time of vulnerability and risk, it is also a time of opportunity. While adolescents tend to be resilient and responsive to change, they seem to struggle with getting enough sleep. She first stressed the importance of sleep by stating that young adolescents require about 8.5–9.5 hours of sleep per night; however, due to biological and social factors, this often does not occur. She gave the example of puberty delaying sleep onset and making it more difficult to fall asleep. She also mentioned the “slow-to-rise phenomenon,” where the delay in falling asleep also makes it difficult for adolescents to wake up early. Adolescent students are more likely to have more freedom over when they go to bed. She described the potential desire to continue

socializing with their friends through the evening and into the night. Additionally, academic work may keep them up longer at night. Lastly, most secondary schools start before 8:30 a.m., the earliest recommended start time per the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2014). These factors all lead to sleep deficit, which impairs cognitive functioning.

Williams described a study that found that other developmental risk factors were tobacco, e-cigarettes, and vaping. The study showed that while tobacco use has held constant, e-cigarette and vaping use have risen. Specifically, e-cigarette use has increased from 0.5 percent in 2011 to about 5 percent in 2018. A cross-sectional survey conducted in 2019 reported the prevalence of self-reported current e-cigarette use at 10.5 percent among middle school students (Cullen et al., 2019).

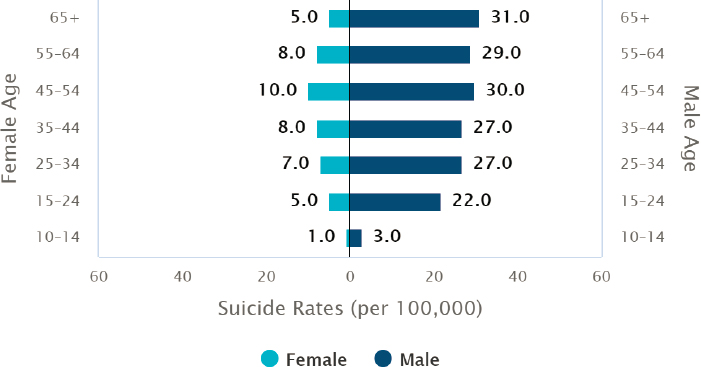

Williams described developmental changes as making adolescents vulnerable to mental health concerns, particularly suicide. She illustrated this point using data from the National Institute of Mental Health. Overall, adolescents aged 10–14 have a low suicide rate, though boys and men across all ages have an increased rate compared to girls and women. Figure 2-2 shows the crude 2017 suicide rates by sex and age categories, with an upward trend for children aged 12 to 14 (NIMH, 2019).

The last risk factor mentioned by Williams was the lack of equity in education and educational systems. Systematic discrimination and bias especially target those from historically marginalized groups. As Williams alluded to previously, children “are developing their identities,” making them “more aware of stereotypes.” This new awareness also applies to bias from school staff, including teachers, which may “undermine trust and a sense of belonging and performance in middle school.”

SOURCES: Williams presentation, December 5, 2019; NIMH, 2019.

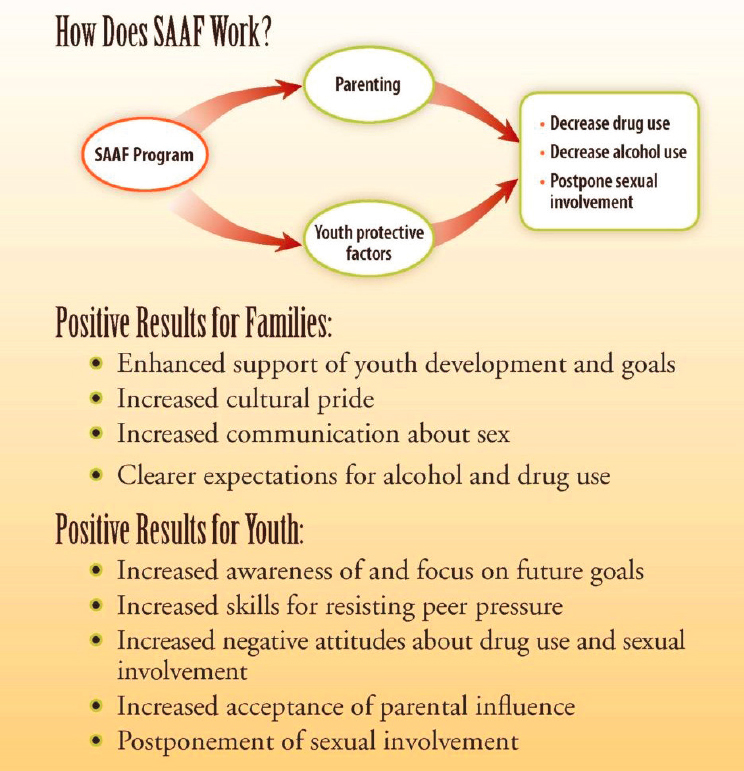

Williams discussed three protective factors for positive adolescent development. First was the need to focus on families, cultural identity, and parent–youth relationships. Williams gave the example of the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program (CFR, 2010) (see Figure 2-3). She stated that SAAF focuses on African American parents and adolescents in low-income rural areas and includes various caregiver, youth, and family topics that promoted positive identity, self-esteem, and parenting tools. Its outcomes were positive racial identity, increased ability to deal with racial discrimination, and increased self-esteem. It also had positive physical health impacts; a reduction in insulin levels was found 19 years after participation (CFR, 2010).

SOURCES: Williams presentation, December 5, 2019; CFR, 2010.

The next protective factor that Williams described was developmentally responsive practices. Interventions need to be responsive to early adolescents’ awareness of and sensitivity to social status and respect. Williams listed three approaches for this. The first and second approaches are to harness the desire for status and respect, while lessening the influence of status and respect threats. An example is to stress their sense of agency and power while resisting risks. The third approach is to make interactions with adults more respectful. This develops relationships by focusing on an empathetic approach to discipline.

The last protective factor is to promote sleep by monitoring bedtime, restricting nighttime screen usage, providing a comfortable pillow, and instituting later school start times. A 2018 study of 421 Mexican American adolescents found that consistent sleep was associated with the highest levels of academic achievement and mental health outcomes and that having a comfortable pillow helped with their quality of sleep (Fuligni et al., 2018).

Next, Tamayo began his presentation by asking how to “effectively enable [educators] to promote the conditions that are going to allow for whole child education and support that unleash the potential of all of our kids.” He approached this question by exploring three main ideas: initial findings on learning and development, barriers that educators face, and supportive practices and policies within educational systems to promote success.

Before diving into these topics, Tamayo led an audience participation activity. He conducted a guided reflection on middle school, asking the audience to think and feel about how they learn best, how they felt about their own middle school experience, in what ways those experiences were positive or negative, and how they have been long lasting. After internal reflection, audience members were directed to discuss their responses with those sitting next to them and then with the larger group. Audience members shared positive experiences, such as strong friendships and a sense of belonging. One negative experience that an audience member described was being taller than others in middle school and hitting his head on a speed limit sign. He was embarrassed, and his friends laughed at him; he still blamed himself for causing himself embarrassment. Another mixed experience shared by an audience member was completing a mathematical formula on the board in front of the class. The teacher commended her abilities and called her “bright,” which she had not thought of herself as previously. This experience turned negative as other students began to bully her for thinking she was smarter than they were. She expressed her resistance to receiving accolades or being singled out in front of others.

Tamayo then discussed how students’ situations (learning disabilities, family structures, poverty, or affluence) impact their learning abilities. He stated that age does not necessarily align with its developmental stage, which makes each child unique. This poses a particular challenge for educators and systems. Tamayo argued that the current educational system “no longer [meets] … our challenges or our moral imperative to support every single child individually in this country.” In other words, it serves the group, which creates a disservice to individual children by penalizing and rewarding them unfairly based on which groups they belong to and whether they deviate from the expected average. Tamayo said that students who tend to perform outside the expected average are often persons of color and at a disadvantage because systematic racism and other biases continue to infiltrate the educational system.

Tamayo further discussed his point of focusing on individual students, which has advantages and disadvantages as well as implications for educational practice and policy. When focusing on one child, there is a shift to thinking that that child has both the opportunity to learn and the unique potential to achieve. When focusing on the group, larger systemic barriers are often shifted to a different system or agency to battle. Coming from a background teaching American history and government, Tamayo applied key concepts, such as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and what that means for [the] individual child” in shaping their future and learning. These concepts are becoming more prominent within the education field in discussing education and expectations for students. Equity, social-emotional development, skills, relationships, and positive mental health experiences are becoming priorities in the field.

Tamayo touched on the Science of Learning & Development (SoLD) Alliance, which aims to take the body of research on education, equity, and excellence and bring it to practitioners and policy makers to use in learning environments (SoLD Alliance, 2019). It promotes the idea that each child is unique and has near unlimited potential and that educational systems should approach students where they are because they have different needs, including integrated experiences, academic topics, and social and emotional skills.

Tamayo concluded by defining various aspects of policy to support this context. First, he stated there should be a “whole child vision” in which the educational system serves all aspects of development and growth, not just academic success in the traditional sense. Next, he said there should be appropriate and effective funding to support educational systems and their members. Additionally, Tamayo asserted that knowledge-sharing systems should be integrated and intentional to connect research literature to those in practice and policy.

DISCUSSION

Next, there was a brief discussion and a question-and-answer session with the audience. Michelle Larkin, the moderator, initiated the discussion by asking the panel about potential changes to educational systems, such as later start times, that research supports as positive for cognitive development but that have not yet been enacted. Williams responded that the reasons are often logistical challenges, such as transportation, extracurricular activity coordination, and teacher and family needs. She said that there may be changes with enough political will and pressure. In the meantime, Williams noted that smaller changes, such as monitoring bedtime and limiting activities and workload after school hours, may help to alleviate some of the burden.

John Auerbach of Trust for America’s Health shared his concern that schools focus only on events that occur during the school day rather than assisting families with issues outside of school and at home, including racism and poverty. He asked the panel for their opinions. Fagell responded that as a counselor, she often dealt with these external issues, but many teachers did not feel they had adequate training to confront them. As she mentioned in her presentation, some teachers self-identify as helpers, meaning they do not have to solve the problem or act as a liaison but can help to a level dictated by their specific scope of training. Williams discussed the need for a multisector approach (see Chapter 4). Tamayo pointed out an error in the general mindset that performance is only influenced by the events of the school day. He stated that without understanding the individual child and their uniqueness, educators will not be able to maximize resources.

A roundtable member representing The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School asked about suicide attempts and ideation and if first-aid training in mental health may be a positive strategy. Fagell responded by describing typical characteristics of middle schoolers. She shared that they typically do not seek out others for help or know when to ask for help, have not clearly defined their emotions, and do not know what clinical depression is or looks like. Fagell shared that about 20 percent of children have anxiety or depression, which has risen over the years. She mentioned programs that train children to identify harmful behaviors or thoughts in themselves and others and to understand why seeking help from adults is necessary. Fagell felt that validating their feelings, normalizing help-seeking behavior, and empowering them would help address mental health concerns. Tamayo added that young adolescents can be malleable and thus need to be surrounded by adults giving positive messages about resiliency, agency, and confidence.