5

Developing a Sustainability Workforce

Chapter 3 outlines the conceptual underpinnings necessary for a robust sustainability curriculum, which include the need to develop competency in five realms, to develop capacities to act on these competencies, and to have the knowledge foundation to build on these capacities in a variety of contexts. Chapter 4 examined how these concepts are realized in institutions, and how to address impeding factors. In Chapter 5, the focus turns to developing and supporting the individual student, maintaining that a sustainability graduate can become, ideally, an agent of change to create a more sustainable world.

CONSIDERATIONS BEYOND THE ACADEMIC

Before summarizing the research and related information about developing change agents, it is important to recognize a self-evident and sometimes ignored reality. Simply put, students are individuals who do not abandon their identities when they enter a classroom or work at a field site. This reality was expressed by workshop participants in different ways—in the challenges they face and how sustainability programs can offer some solutions.

Students face many economic pressures. As noted in Chapter 3, students may be unable to take advantage of experiential learning opportunities in different locations that require additional travel costs or unpaid/underpaid internships. Even with financial aid, students are faced with high living costs that lead them to take on one or more jobs. The Urban Institute estimates that 11 percent of students in 4-year colleges experience food insecurity (Blagg et al., 2017). An administrator at the University of California, Santa Cruz, the site of the committee’s third workshop, acknowledged the impact of the area’s high cost of living on

student well-being. The farm run by the university’s Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems was set up more than 50 years ago to experiment with different types of plant and animal products. Its harvests now also go to provide fresh produce, ready-to-eat meals, and other food at a low cost to students.

Many students entering sustainability courses and degree programs are propelled by a desire to change the world. Some of those students come from communities and neighborhoods that are themselves disproportionately affected by poverty, climate change, air pollution, unsafe drinking water, and other problems. One student from the Santa Cruz workshop reported a dean at another university asserting to her that environmental justice was not an “academic discipline” and therefore had no part in the classroom. Yet, drawing on these lived experiences can improve the learning outcomes for all.

The idea of “wraparound services” has gained traction in higher education. While it is beyond the scope of this report to go into these services in detail, several participants pointed out that students must have sustainability in their own life to become an effective sustainability student and, ultimately, sustainability professional.

DEVELOPING CHANGE AGENTS

Theory and research regarding the role of change agents in achieving SDGs provides important insights into the design of sustainability programs. Change agents are people who play a significant role in “initiating, managing, or implementing change” (Caldwell, 2003). To address complex sustainability issues, change agents may be challenging long-held assumptions, practices, and/or policies. According to Van Poeck et al. (2017), change agency “is always related to political struggles on what, how, who, why, and when to change.” Further, they state, change agents need to understand the technical or scientific solutions, but that is not enough: “Rather, it is a matter of engaging with the multi-dynamic complexity of wicked problems, including tensions between stability and change, short term and long term, local and global, rich and poor, etc.”

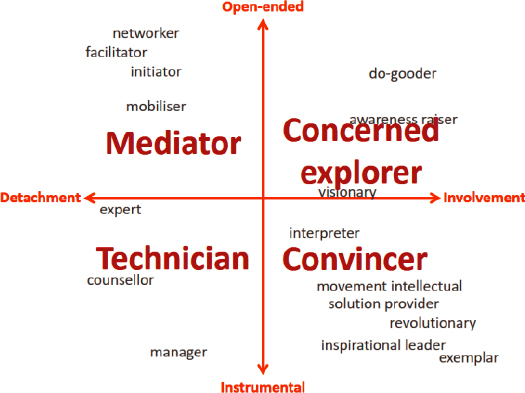

An analysis by Van Poeck et al. (2017) drew on examples of change agents in varied sustainability education settings in Belgium and Denmark. The authors mapped the roles that change agents played on two axes (see Figure 5-1). The vertical axis looked at instrumental versus open-ended agency: in other words, operating more as a networker or facilitator (open-ended) versus more as a manager or exemplar (instrumental). The second axis graphs personal detachment versus involvement. Against these axes, they identified four main types of sustainability change agents: Technician, Convincer, Mediator, and Concerned Explorer. A change agent’s role and performance will change over time, depending on the challenge at hand, the circumstances, the stages in the person’s career, and other factors.

Sustainability practitioners can draw from other change management models. For example, the Situational Leadership Model, developed by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard and first introduced as the “Life Cycle of Leadership” (Hersey and

SOURCE: Van Poeck et al. (2017).

Blanchard, 1969), proposes a taxonomy consisting of four leadership styles, including telling, selling, participating, and delegating, and a framework for matching each style to specific situations (Thompson and Glasø, 2015). The model asserts that successful leadership is both task relevant and relationship relevant, and leaders adapt their management style based on groups and individuals according to the situation as they possess different levels of capability and experience. Another example includes the Cohen-Bradford Model of Influence without Authority developed by Allen R. Cohen and David L. Bradford. The model consists of six steps for how to influence others when authority is not present, including (1) assume all are potential allies; (2) clarify your goals and priorities; (3) diagnose the world of the other person; (4) identify relevant currencies, theirs, yours; (5) dealing with relationship; and (6) influence through give and take (Cohen and Bradford, 2005).

Workshop participants concurred with the idea that sustainability programs have a role to play in preparing their students to become change agents—while in school and in their careers. They noted that students often enter their programs already motivated to effect change, but they require knowledge and skills to do so. In addition to the competencies and content areas described in Chapter 3, students need to understand theories of change and leadership. A three-level youth engagement model, in which students start by working on a project, then serve in an advisory role, and then feel prepared to take leadership, was provided by one workshop participant as an example for preparing students for leadership and independence.1 Workshop participants also emphasized the power of agile learning

___________________

1 See Act for Youth’s statement on youth engagement in organizations, available at http://actforyouth.net/youth_development/engagement, accessed on March 11, 2020.

methods for leadership training in innovation to solve complex sustainability challenges. One example is the Blue Pioneers Program’s training of innovation leaders to solve ocean sustainability challenges via the raw case method (see Box 5-1).

A network of higher education institutions known as A Network for Graduate Leadership in Sustainability, or ANGLES, was formed to encourage leadership

development for sustainability graduate students (see Box 5-2). The ANGLES network encourages the “entire higher education enterprise to become change agents in order to deal with today’s sustainability challenges at multiple levels of agency: as individuals, communities, organizations, networks and systems” (Kremers et al., 2019). The network has identified five critical change-agent capacities: (1) transdisciplinary collaboration and community; (2) intellect and innovation; (3) emotional intelligence and well-being; (4) energy and commitment; and (5) reflexivity, reflection, and action (Kremers et al., 2019). Net Impact is an organization that mobilizes next-generation emerging leaders to use their skills and careers to make a positive impact in the world (Net Impact, 2020). With more than 400 chapters in nearly 40 countries, the organization supports a global network made up of local chapters on university campuses, in cities, and in companies, and runs programs, campaigns, and events to help students build leadership skills and experiences related to sustainability.

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals will require change agents from multiple disciplines beyond the small percentage who study sustainability in depth (i.e., undergraduate majors or minors and/or as graduate students). All students must feel empowered to create change for a better future. As one participant noted, “Every student will have to deal with sustainability in his or her [or

their] lifetime.” One idea proposed was establishing a core requirement course across the academy to teach sustainability principles, which would then serve as a reference when embarking on other fields. A participant at the Washington, D.C., workshop noted that students are demanding to be listened to as partners and demanding transparency and accountability, sincerity, and authenticity. Rage and anger is what propels social justice, another said, but a positive vision can help create sustained change.

An academic program in sustainability, with its roots in evidence and objectivity, traditionally does not teach “rage and anger,” nor should it. As one participant urged, “Students need to go beyond their passions and learn evidence-based decision-making, then how to communicate and persuade to implement change.” These are within the purview of a strong sustainability program.

Sustainability by its nature disrupts the status quo in many domains and will require the development of a sustainability workforce that is capable of guiding effective transitions to sustainable practices. Students are entering sustainability programs with the desire to “change the world for the better.” Academic programs can harness this motivation with the necessary competencies, knowledge, and skills described in this report. As such, the committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 5.1: Completion of a sustainability program in higher education should improve students’ ability to design, implement, and lead proactive change toward a sustainable world. Thus, sustainability education programs should provide training and mentoring support to enhance capacities of their graduates to translate knowledge to effective action to meet emerging local, regional, national, and global needs.

ENHANCING COLLABORATION AMONG SUSTAINABILITY PROFESSIONAL SOCIETIES

As sustainability programs emerge and evolve, students, faculty, and program directors would benefit from opportunities to share best practices, obtain guidance on career paths for students, and join a network or community to share ideas and develop shared principles and values. Professional societies play a role in facilitating community building and resource sharing through convening groups. They also present an entity that can set standards and determine parameters for program evaluations and potential accreditation, as well as lead efforts for standardized data collection about students, employees, and employers. Such capabilities would be valuable to both sustainability education programs and the sustainability workforce. Professional societies are also responsible for setting the standards for professional actions and behaviors by that profession.

A number of organizations are helping to shape the landscape for sustainability educators, students, and professionals, including the following:

- Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE):2 Launched in 2005, its mission is “inspiring higher education to lead the sustainability transition.” AASHE holds an annual conference for sustainability educators in higher education institutions. Many universities participate in its Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System, which measures sustainability performance of higher education institutions, with an increasing emphasis on adoption and delivery of sustainability curricula. Through the system, universities receive a medal ranking—bronze, silver, gold, or platinum. AASHE also offers professional development training along with toolkits and resources. As of this writing, it has 719 members in North America.

- National Council for Science and the Environment (NCSE):3 Established in 1990, NCSE’s mission is to “improve the scientific basis of environmental policy and decision making.” Member institutions include approximately 100 universities and colleges, 20 community colleges or college districts, and 2 international university members (this latter program was just launched). The NCSE Alliance of Sustainability and Environmental Academic Leaders (formerly known as the Council of Environmental Deans and Directors) meets twice per year, engages in communities of practice (including one on sustainability education), engages with policy makers in an Academic-Federal Dialog, and receives training on science policy communications.

- Second Nature:4 Founded in 1993, the mission of Second Nature is a commitment to “accelerating climate action in, and through, higher education.” In 2006, it launched the Presidents’ Climate Leadership Commitments with dedicated targets for climate change action. This initiative formed the basis for the Climate Leadership Network, which includes more than 600 universities and colleges. The organization provides grant funds, solutions toolsets, convenings, and other activities to forward climate change action with universities and colleges.

- Sustainability Curriculum Consortium (SCC):5 The purpose of the SCC is to build “collective capacity as educators and change agents, along with the administrators and stakeholders who can support them, to improve the way sustainability is perceived, modeled, and taught.” Through webinars and other convenings, the SCC brings together experts on sustainability

___________________

2 See http://www.aashe.org, accessed on March 10, 2020.

3 See https://www.ncseglobal.org, accessed on March 10, 2020.

4 See https://secondnature.org, accessed on March 10, 2020.

5 See http://curriculumforsustainability.org, accessed on March 10, 2020.

-

curricula to share best practices and ideas and seek partnership opportunities for sustainability educators.

- International Society of Sustainability Professionals:6 The mission of the society is to “advance sustainability in organizations and communities around the globe.” It provides collaboration and partnership opportunities for members as well as training, including a Sustainability Professional Certification offered in partnership with Green Business Certification Inc.

- Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences (AESS). The AESS is a “faculty-and-student-based professional association in higher education, designed to serve the needs of environmental scholars and scientists who value interdisciplinary approaches to research, teaching, and problem-solving” (AESS, 2020). The AESS has held an annual meeting since 2009 to address an interdisciplinary approach to environmental issues and sustainability.

- National Association of Environmental Professionals (NAEP). The mission of the association is “to be the interdisciplinary organization dedicated to developing the highest standards of ethics and proficiency in the environmental professions” (NAEP, 2020). It is designed for professionals from the public and private sectors to promote excellence in decisionmaking relating to environmental, social, and economic impacts.

Corporate sustainability organizations continue to grow, reflecting the change in sustainability as a “nice to have” or form of corporate social responsibility to the recognition of sustainability as a “need to have” and for establishing competitive advantage. Some examples include GreenBiz, Ceres, Sustainable Brands, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.7 Alongside these have grown sustainability-reporting organizations for businesses such as CDP (formerly Carbon Disclosure Project), Global Reporting Initiative, and the United Nations Global Compact initiative.8 Successful sustainability education programs will need to pay attention to trends and needs identified by these organizations for both curriculum development and career pathways in sustainability.

During the committee’s second workshop in Washington, D.C., a participant suggested the need to create peer-to-peer networks on two levels: among leadership (embodied by the Council of Environmental Deans and Directors, since renamed to the Alliance of Sustainability and Environmental Academic Leaders) and through a professional society (through the Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences). Including a research component and opportunities for interfacing between academics and the user community are also important, as the annual

___________________

6 See https://www.sustainabilityprofessionals.org, accessed on March 10, 2020.

7 See https://www.greenbiz.com, https://www.ceres.org, https://sustainablebrands.com, and https://www.wbcsd.org, all accessed on March 10, 2020.

8 See https://www.cdp.net/en, https://www.globalreporting.org, and https://www.unglobalcompact.org, all accessed on March 10, 2020.

conference of the NCSE provides. Another participant supported these ideas, but emphasized that sustainability includes more fields than environmental science. Several participants said they would find value in the networking and leadership opportunities that a professional society could offer, although it was pointed out that it would be a challenge to balance the multiple disciplines that make up the field with providing relevant information and opportunities. Despite the challenge, many participants, especially those starting out in their careers, expressed the desire to be part of the kind of community that a professional society could offer.

ACCREDITATION

One role played by professional societies in the United States is to serve as an accreditor. More than 50 professional societies accredit the college and university programs in their areas of expertise.9 The committee’s statement of task (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1) requested that the committee consider the feasibility of accreditation of sustainability programs to strengthen them and to further engage with the Sustainable Development Goals. According to the U.S. Department of Education, which oversees accrediting organizations, benefits of accreditation include the following:

- Creating a culture of continuous improvement of academic quality at colleges and universities and stimulating a general raising of standards among educational institutions.

- Involving faculty and staff comprehensively in institutional evaluation and planning.

- Establishing criteria for professional certification and licensure and for upgrading courses offering such preparation.

- Assessing the quality of academic programs at institutions of higher education.

At all three workshops, the committee posed a series of questions to elicit the perspectives of educators and end users on the desirability of accreditation for sustainability programs. While participants agreed about the need to strengthen existing sustainability programs and provide guidance for emerging ones, no clear consensus emerged on the topic. Some participants saw accreditation as a way to build credibility and to improve programs. Several drew upon other efforts they have been involved in or observed. Public administration was referred to as an example of a discipline that has gained in stature since accreditation began in

___________________

9 See Department of Energy, available at https://www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/accreditation.html#history, accessed on April 10, 2020.

1970.10 In contrast to this relatively recent effort, another said her forestry and natural resources department has been involved in accreditation carried out by the Society of American Foresters since 1935. She pointed to the value of the periodic examination not only for the external review but also as a process of reflection for the faculty, students, and administration. One workshop participant noted accreditation can provide greater legitimacy to a field of study, with public policy and landscape architecture as examples. Another suggested that accreditation could help break down the disciplinary silos identified as an impediment, build a cross-cutting program, and provide some value as a credential, especially small institutions that might see it as a valuable counterweight to larger ones.

Others, however, expressed concern that accreditation would pose an obstacle or a bar to entry. An institution may decide not to expand or initiate a program with accreditation requirements. For example, the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology has been evaluating chemical engineering programs at universities in the United States since the 1930s; however, California Institute of Technology’s chemical engineering department and Stanford University have recently decided not to pursue accreditation in order to modernize their curricula and offer students more flexibility in designing programs (Arnaud, 2017). Accreditation might hamper diversity efforts, a few people pointed out, especially if less-resourced schools where underrepresented minorities attend in greater numbers are discouraged from the field. Another concern related to employment security, including people already in the workplace, if an applicant had not graduated from an “accredited program.”

End users at the workshops did not consider accreditation a critical aspect in their hiring. While they said they did require graduation from an accredited program vital in fields such as architecture, several said they are more concerned with a sustainability applicant’s course work, internships, and competencies. Another employer said she envisioned a future in which “all jobs become sustainability jobs,” and accreditation would narrow, rather than broaden, the field.

Many workshop participants pointed to certifications that individuals could earn and may be considered more valuable to an employer than accreditation of their colleges and universities; examples cited included the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 14001 requirements for environmental management systems and the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification, among others.11 A benefit in such programs is that individuals must continue their education and training to remain certified.

In consideration of possible accreditation in the future, several participants suggested strategies that are more voluntary and less rigorous than a full-bore

___________________

10 Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration is the accrediting body—self-described as the “Global Standard in Public Service Education Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and Administration.”

11 See ISO 14000, available at https://www.iso.org/iso-14001-environmental-management.html; LEED rating system, available at https://www.usgbc.org/leed; both accessed on March 12, 2020.

accreditation program, yet still useful to students and other stakeholders. The Canadian Environmental Certification Approvals Board was mentioned as one such assessment that might serve as, at least in the short to medium term, a way for programs to self-measure their performance.

The Sustainability Curriculum Consortium and National Council on Science and the Environment have had some discussions about accreditation, according to several workshop participants familiar with the effort. They felt that agreement over a common body of knowledge for sustainability needs to emerge first. During this report’s preparation, a community of practice was established within the Council of Environmental Deans and Directors, facilitated by the NCSE (currently known as the Alliance of Sustainability and Environmental Academic Leaders), and this would be a useful development to track.

As sustainability education programs continue to increase and evolve, it is important for existing professional societies concerned with sustainability to consider strategies that could strengthen higher education programs. Such strategies could include opportunities for professional development, networking, collaboration, and data collection, and the development of metrics for assessing, certifying, and/or accrediting programs. Additionally, industries could work with these organizations to meet sustainability goals and objectives, establish targets, and encourage students to bring innovation and creativity to address sustainability challenges and opportunities. Therefore, the committee recommends the following:

Recommendation 5.2: Professional societies focusing on sustainability education should pursue collaborative opportunities to (i) provide forums for convening sustainability students, researchers, and professionals; (ii) build partnerships with the public and the private sectors; (iii) offer formalized training and mentorship; (iv) promote information sharing; (v) develop shared principles and values; (vi) establish a model for assessing sustainability programs; and (vii) establish and lead a cross-sectoral effort to track and analyze employment in sustainability-focused jobs.

REFERENCES

Arnaud, C. H. 2017. Is it time to leave behind chemical engineering accreditation? Chemical & Engineering News 95(48), 20–22. https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i48/time-leave-behind-chemicalengineering.html, accessed on June 15, 2020.

AESS (Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences). 2020. https://aessconference.org, accessed on May 18, 2020.

Blagg, K., C. Gundersen, D. W. Schanzenback, and J. P. Ziliak. 2017. Assessing Food Insecurity on Campus: A National Look at Food Insecurity Among America’s College Students. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Caldwell, R. 2003. Models of change agency: A fourfold classification. British Journal of Management (14)2, 131–142. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-8551.00270.

Cohen, A. R., and D. L. Bradford. 2005. Influence without Authority, Second Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. https://dongengbudaya.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/1472.pdf, accessed on June 15, 2020.

Hersey, P., and K. Blanchard. 1969. Life-cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal 23, 26–34.

Kremers, K. L., A. S. Liepins, and A. M. York (eds.). 2019. Developing change agents: Innovative practices for sustainability leadership. ANGLES (A Network for Graduate Leadership in Sustainability). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Libraries. https://open.lib.umn.edu/changeagents.

NAEP (National Association of Environmental Professionals). 2020. https://www.naep.org, accessed on May 18, 2020.

Net Impact. 2020. https://www.netimpact.org, accessed on May 18, 2020.

Rittel, H. W. J., and M. M. Weber. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences 4(2), 155–169.

Thompson, G., and L. Glasø. 2015. Situational leadership theory: A test from three perspectives. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 36(5), 527–544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2013-0130.

Van Poeck, K., J. Læssøe, and T. Block. 2017. An exploration of sustainability change agents as facilitators of nonformal learning: Mapping a moving and intertwined landscape. Ecology and Society 22(2).