5

Transformation of the Food System

The final session of the workshop, moderated by Christian Peters, Tufts University, focused on transformation of the food system. Speakers addressed both production- and consumption-oriented strategies for effecting this transformation and the necessary supporting policies.

INTRODUCTION

Peters began by providing a recap of the first two sessions (see Chapters 2, 3, and 4) and then introduced the third. He noted that the workshop was designed so that all sessions would be interdisciplinary and would address both short-term issues, such as COVID-19, and long-term issues, such as climate change.

Recap of Day 1

Peters summarized key points from Stover’s introductory remarks at the beginning of the workshop and the presentations during the first two sessions on day 1. He added that while the food system historically was expected to provide “food, feed, and fiber,” it now is also expected to improve human health, reduce the ecological footprint of the food produced, and move from being a carbon source to a carbon sink. Sharing a diagram of an agricultural paradigm from a 1999 report (Welch and Graham, 1999), Peters pointed to expanding expectations that include production and sustainability paradigms as part of a broader food system. The production paradigm is focused on productivity and efficiency, he elaborated, while

the sustainability paradigm is focused on ecological impact. In addition to production and sustainability, Peters observed, new expectations for the food system consider human health and human needs.

Introduction to Day 2

Setting the stage for Session 3, Peters posed the question of what the goals are for transformation of the food system. Referencing the Brundtland report, he defined sustainable development as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). He highlighted two key concepts from that report: that the essential needs of the world’s poor should be a priority, and that technology and social organization limit the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs. Peters shared the 17 United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established in 2015, noting that they are a holistic international agenda for achieving sustainable development. The SDGs, he explained, address the following topics: (1) poverty; (2) hunger; (3) health and well-being; (4) education; (5) gender equality; (6) clean water and sanitation; (7) clean energy; (8) work and economic growth; (9) industry innovation; (10) inequalities; (11) sustainable cities and communities; (12) responsible consumption and production; (13) climate action; (14) life below water; (15) life on land; (16) peace, justice, and strong institutions; and (17) partnership. Overall, he elaborated, the SDGs contain 169 targets.

Peters then described several of the 2030 targets included in SDG 2, to end hunger. For example, Target 2.1 is to end hunger and ensure access to adequate nutrition by all people; Target 2.2 is to end all forms of malnutrition; Target 2.3 is to double agricultural productivity and the incomes of small-scale food producers; Target 2.4 is to ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production; and Target 2.5 is focused on maintaining the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants, and animals. Unlike the other targets with a deadline of 2030, Peters noted, Target 2.5 had a deadline of 2020. He added that while the SDGs and their many targets could be perceived as a laundry list of activities, he reiterated that the SDG framework provides a holistic way of viewing the needs for sustainable development.

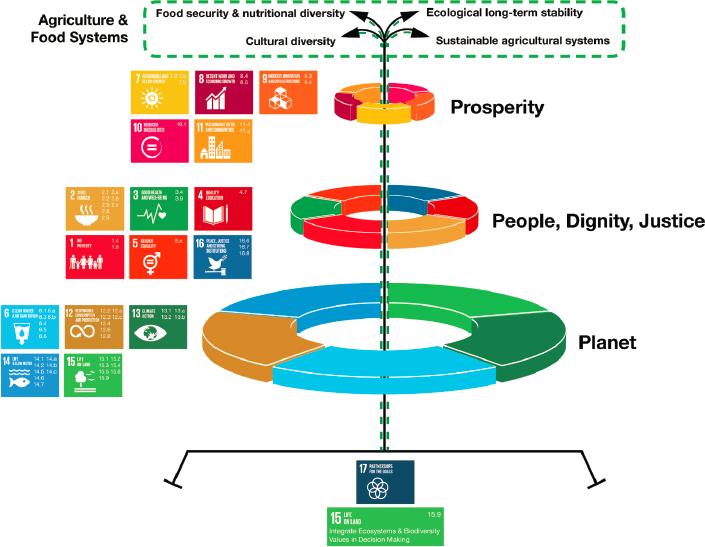

Peters next presented a diagram of agriculture and food systems from The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (see Figure 5-1), which depicts how the 17 SDGs fit into the categories of (1) planet; (2) people, dignity, and justice; and (3) prosperity. He pointed out that relevant outcomes include food security and nutritional diversity, cultural diversity, long-term ecological stability, and sustainable agriculture systems. He also

SOURCES: Presented by Christian Peters on July 23, 2020; TEEB, 2018. Reprinted with permission from the United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment).

noted that the relevance of the SDGs highlights that the issues discussed in the workshop are timely and of international importance.

Peters spent the rest of his presentation focused on the question of how to create a transformed food system. He outlined possible strategies for feeding the world’s population and achieving food security included in a 2010 paper titled “Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People,” which at the time was the projected global population in 2050 (Godfray et al., 2010). These strategies, he continued, include the production-oriented strategies of increasing the yield potential, closing yield gaps by applying available technologies and increasing productivity, and expanding aquaculture; the supply chain strategy of reducing food losses; and the consumption strategy of changing the mix of plant- and animal-based foods in people’s diets.

Peters also discussed Figure 2-1 in Chapter 2 as a roadmap for implementing the above strategies, highlighting the supply chain elements

and emphasizing the importance of working at multiple levels and within multiple dimensions of the food system. He pointed out that this figure shows food and food services flowing toward the consumer and money and demand information flowing toward the farmer. Additional domains that interact with the food system, he observed, include organizations, the health care system, science and technologies, the biophysical environment, policies, and markets.

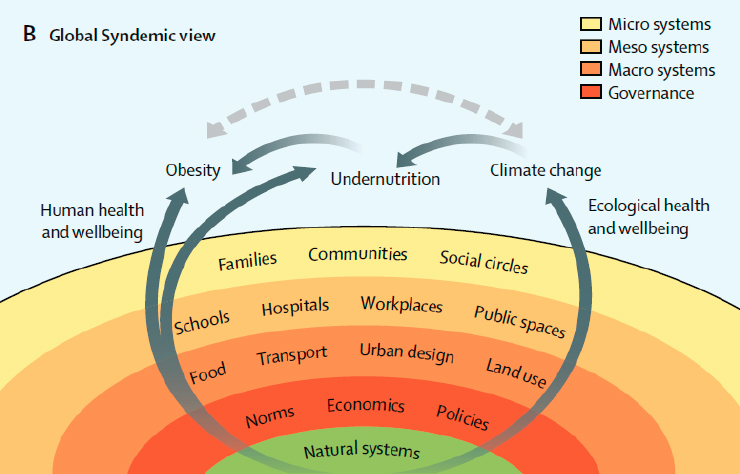

Referencing a figure from a recent paper on the coexisting and interrelated health crises of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change (see Figure 5-2), Peters stressed the importance of working at multiple scales, including natural systems; cultural norms and policies; governance systems; macrosystems, such as transportation and human design; mesosystems, such as schools, hospitals, and workplaces; and microsystems, such as families and communities.

Finally, Peters informed the audience that the four speakers to follow would address different aspects of food system transformation, including incentives, consumption-oriented strategies across the value chain, design strategies for preferred food futures, and policy approaches to enable pathways for change.

SOURCES: Presented by Christian Peters on July 23, 2020; Swinburn et al., 2019. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Addressing a question from Naomi Fukagawa about whether to start with food system transformation at the local, national, or global level, Peters responded that he sees impact at each level as the sum of impacts at the level below. He suggested that the level at which to start depends on where there is readiness for change.

INCENTIVIZING FOOD SYSTEMS TRANSFORMATION

Pradeep Prabhala, McKinsey & Company, spoke about incentivizing food systems transformation. Framing the context for his presentation, he noted that progress toward the SDGs has been uneven as food systems have been focused primarily on increasing production and addressing hunger and malnutrition, but have made little progress toward protecting the environment or advancing integrated health outcomes. Prabhala observed that the food system accounts for about $10 trillion in economic value and about $12 trillion in external costs, meaning that the sector overall generates more costs than benefits. Many of these costs, he added, are borne by the health and environmental sectors.

As Prabhala explained, an ideal food system should be inclusive, sustainable, efficient, and nutritious. Successes to date, he reported, have included productivity gains in food production following the 2008 food crisis and progress toward addressing hunger and malnutrition. Global challenges, he continued, include degradation of 95 percent of the world’s land by 2050, one in five children experiencing stunting due to undernutrition, two in five adults having overweight or obesity, and food loss costing $940 billion annually. He noted that strategies for increasing production do not necessarily address these other challenges.

Transformation requires fundamentally changing the way food is both produced and consumed, Prabhala asserted, including getting 500 million farmers globally to change their farming practices and 7.7 billion consumers to change their consumption patterns. Responding to an audience member’s question, he stated that in countries with consolidated agricultural systems, the large players have significant influence over small shareholder farmers, but this is not the case in all countries. Challenges to achieving the necessary changes, he explained, are economic, educational, and attitudinal. For example, he pointed out that many smallholder farmers will not make changes unless they are financially beneficial, while others lack knowledge about the changes that are needed or do not want to make changes to long-standing habits.

Prabhala suggested that incentives are needed for both producers and consumers to make the needed changes. He argued that effective incentives should fund the costs of behavior change, mitigate transition or switching costs, and cover ongoing economic costs of the change. He also stressed

the need to remove or restructure disincentives, including $100 billion in government subsidies for the agriculture sector.

Food System Incentive Pathways

Prabhala proposed four pathways for incentivizing key actors to create a food system that is sustainable, nutritious, inclusive, and efficient. The first he termed “repurposing public investment and policies,” which involves changing how and why governments spend money and constructing effective policies. He noted that governments often spend money in an attempt to balance social, economic, and other outcomes, and stated that alternative solutions must replace those investments. He cited as an example of an effective policy a tax on carbon to offset the carbon being produced through agriculture. The second pathway is what Prabhala termed “business model innovation,” which involves changing the way companies do business through technology, product innovation, or innovation in business models in a way that creates the appropriate incentives. Prabhala identified the third pathway as the “institutional investment pathway,” which involves investors setting standards for how their money is spent. Prabhala noted that some investors set such standards in response to data on the economic risk posed by climate change. Finally, he described the “consumer behavior change pathway,” based on recognition that consumer demand can lead to changes in other parts of the ecosystem.

According to Prabhala, these four pathways are interconnected, and they all involve either policy or business model changes. He pointed out, however, that different pathways are appropriate for different countries and contexts, and that trade-offs in their implementation must be managed. He added that many of the necessary changes will happen at the national rather than the international level.

Activating the Pathways

Prabhala then provided a few examples of how the pathways he had described have been activated and challenges overcome, noting that various constraints often prevent the pathways from being activated effectively.

With respect to repurposing public investment and policies, Prabhala posited that governments may make suboptimal decisions about the food system because of the siloed nature of government operations and a lack of communication across ministries. In addition, he said the evidence for interventions may be limited, and governments want to scale programs only if they are known to be effective. Lack of political will, stakeholder resistance, lack of capacity for systemic change, and transition costs can

also present barriers, he observed. He noted that in emerging markets in particular, food security is a significant determinant of election outcomes.

Prabhala described some examples of governments that have overcome some of the challenges he outlined. One example he cited was the Great Lakes Protection Fund, through which governors invested collaboratively in projects that could affect the water basin. As another example, he highlighted the Punjab, India, government’s Save Water, Earn Money program, which reduced electricity and water use in agriculture.

With respect to business model innovation, Prabhala identified as a key risk innovating while still making the economic model work, particularly if the innovation is more costly. To illustrate this point, he used the example of consumer food companies that want to innovate to improve the healthfulness of their ingredients but face challenges if consumers are not willing to pay the higher cost of the healthier ingredients. Prabhala stressed the importance of changing business models in the context of the business environment. He also pointed to the need for strong leadership and often a culture change in the way a company does business. In addition, he observed, government could incentivize business model innovation.

With respect to the institutional investment pathway, Prabhala stated that because institutional investors make significant investments in food systems, they have significant influence over the way companies spend their capital. Institutional investors could set clauses that dictate how the capital must be deployed. However, he said, challenges include a lack of intermediation mechanisms to deploy the capital in the intended ways, a lack of understanding of the risk and return of certain investments, and a difficult environment for change. Prabhala suggested that this challenge could be met by channeling institutional capital into natural capital by creating new intermediation mechanisms. As an example of a successful intervention, he pointed to the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program of the World Bank, which works to shift some of the risk away from institutional investors and support their investing in interventions with more inclusive outcomes.

With respect to consumer behavior change, Prabhala emphasized the need for consumers to make sustainable changes in their food choices. He added that some of these changes will require consumer education, and some will require increased support from businesses.

In conclusion, Prabhala stressed the importance of bringing the four pathways together at the country level and aligning actors toward a more inclusive, sustainable, efficient, and nutritious food system.

In response to a question from Peters about a tax on carbon emissions, Prabhala emphasized that the impact of an intervention depends largely on how it is operationalized and implemented. He suggested that in the United States, for example, the carbon footprint of agriculture could be reduced

if farmers adopted regenerative practices that led them to sequester more carbon and reduce the net footprint of their operations. He suggested further that a carbon market could be developed that would verify the farmers’ carbon impact and provide supplemental income to those that adopted the preferable practices. However, he added that in a more fragmented environment, a carbon market would not be possible because the cost of verification would outweigh the benefits. In these environments, he argued, there would need to be alternative policy levers for achieving the intended goal.

CONSUMPTION-ORIENTED STRATEGIES: CONSIDERING THE WHOLE VALUE CHAIN

Philippe Caradec, Danone North America, spoke about consumption-oriented strategies. He asserted that consumers are interested in the value proposition for products, and to be credible and authentic, companies should consider the entire value chain, including the agricultural inputs, food production and processing, brand commitments, and packaging.

Sharing findings from the nationwide Food and Health Survey conducted by the International Food Information Council, of which he is co-chair, Caradec reported that about 60 percent of consumers want food that is produced in an environmentally sustainable way (IFIC, 2020). He identified the top factors that consumers use to determine whether food is produced in a sustainable way: labeling and packaging, such as using recyclable packaging; labeling the food as sustainably sourced, non-GMO (i.e., without genetically modified organisms), locally grown, or organic; and using minimal packaging. Caradec noted that familiarity with regenerative agriculture increased significantly between 2019 and 2020.

Strategies for Addressing Environmental Impact

Caradec provided background on Danone, including the company’s 2030 goals. He described the company as the largest certified public-benefit B corporation in the world, using business as a force for good. A certified B corporation must provide both a return to its investors and a public benefit, he explained, which Danone accomplishes by bringing healthier food to as many people as possible with the lowest environmental impact. In response to a question from Peters, Caradec stated that the company uses its certified B corporation logo and storytelling to educate consumers about Danone’s commitment to addressing climate change. He observed that consumers make a difference when they “vote with their dollars” and purchase products that reflect their values.

Caradec highlighted one of Danone’s 2030 goals in particular: “to serve the food revolution with partners.” He described the company’s emphasis

on partnerships, including the One Planet Business for Biodiversity initiative, which was launched in September 2019 at the UN Climate Action Summit and is part of the French President’s One Planet Lab framework. The coalition is hosted by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Caradec elaborated, and includes 21 companies and organizations collectively worth more than $500 billion. He explained that the Council is focused on agricultural biodiversity, including scaling up of regenerative agriculture, product diversification, and support for high-value ecosystems. Caradec asserted that partnerships with farmers, producers, government, consumers, academia, and civil society are key to achieving these goals.

Business Model Innovation

As an example of how Danone is changing its business model around agricultural inputs, Caradec explained that for a portion of its supply of milk in the United States, the company has reduced the price volatility of milk by using a model that pays for the farmer partner inputs and guarantees farmer partners a specific profit margin. As a result, he added, the farmer partner can try changes in agricultural practices to increase sustainability at scale without bearing the associated risk. Caradec reported that Danone is focusing on soil health, including biodiversity; increased carbon sequestration; and assurance of fair returns per acre. He added that the company also intends to work with farmers to support their implementation of such sustainability practices as low- and no-till farming, use of crop cover, and expansion of biodiversity. Caradec noted that while Danone may suggest changes to farming practices, the farmers themselves make the ultimate decisions about what will work best on their land, and that the program has expanded from 25,000 acres to nearly 60,000 acres in the United States. He also mentioned the Next Frontier Project of Danone’s Horizon Organic brand, which is focused on regenerative soil health, farmer care and safety, and reduced environmental footprint, with the goal of Horizon Organic’s becoming the first carbon-positive brand by 2025.

Packaging Innovation

With respect to packaging, Caradec explained how Danone takes a circular approach and is aiming for 100 percent of its packaging to be reusable, recyclable, or compostable by 2025. He added that Danone has invested in the Closed Loop Fund, focused on packaging collection, sorting, and recycling in secondary markets, as well as consumer education. He stated that the company is also committed to preserving natural resources, including a goal of having 25 percent recycled material in plastic packaging

and 100 percent recycled material in one brand of its plastic water bottles by 2025.

BEYOND RESILIENCE: DESIGN STRATEGIES FOR OUR PREFERRED FOOD FUTURES

Hildreth England, MIT Media Lab, spoke about design strategies for the future food system. Her work is broadly focused on recasting the technology design process to distribute positive impact more equitably and intentionally, in collaboration with and for the most marginalized societies. Her presentation addressed the benefits of thinking like an artist and a designer, why inclusive co-design strategies optimize the food system for all people in the system and promote resilience, examples of using design to make an impact, and co-design principles that are based on her lab’s research.

Introduction

England began by sharing an anecdote from her involvement in user experience testing for a shopping app for mothers participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). A co-worker asked, “Why do they [the WIC mothers] need good design?” This experience and further research on cooperative design principles made England realize that good design is a collective good. All people, she argued, including WIC mothers, farmers, grocery store workers, and other food system stakeholders, respond to, need, and deserve good design.

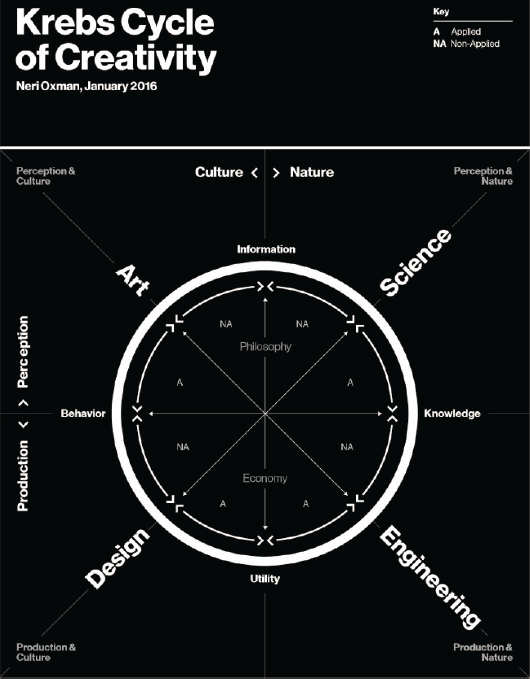

The MIT Media Lab, for which England works, is a research institute that grants a media arts and sciences degree, which combines science and engineering with art and design. An artist, nutritionist, designer, and diplomat, England has dedicated her career to making design choices with the people for whom she is designing. She described how at the MIT Media Lab, bioengineers often collaborate with artists and designers to conduct research in such disciplines as space exploration, social justice, artificial intelligence, robotics, and education. England shared a diagram (see Figure 5-3) illustrating the perpetuation of creative energy, which she described as a compass to guide the infusion of art and design into the food system. England highlighted the fluid movement from one realm to another, making the point that behavior change is both a science and an art.

Benefits of Co-Design Strategies

In considering how to achieve transformation of the food system, England quoted a former director of the MIT Media Lab as saying, “You

SOURCES: Presented by Hildreth England on July 23, 2020; Oxman, 2016. Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Design and Science.

can’t change culture by winning an argument. You change culture by changing hearts and minds.” Art and design are the heart of food system transformation, she asserted, and added that the science of behavior change is about emotions, such as desires, that prompt people to act. She explained that designers use an artist’s perception and stories to produce tools and environments that shift culture and inform science, engineering, and knowledge. She defined culture as “a collection of behaviors at scale shifted by creative perception and production;” in other words, culture is derived from the creation of new habits at scale.

England described how one might approach the food system as an artist and designer, proposing the need for design strategies that integrate emotions into the supply chain. She explained that while tools and technologies

increase efficiency, standardize processes, and improve access, principles optimize for both products and people. Designing for people requires strategy encompassing tools and context, she continued, noting that when people are engaged at scale, there is an opportunity to create a more equitable and sustainable food system that provides agency to its actors. England pointed out that even small design changes can make a major difference in feelings of confidence, self-efficacy, and curiosity.

England emphasized the benefits of design co-creation, particularly with marginalized communities, to balance academic expertise with lived experience and provide for more equal scaled distribution of the design benefits. The food system, she argued, is built on existing inequities and injustice, and co-design allows for the use of design to create more equitable tools in an equitable way and to measure impact. It can also help build social resilience, she asserted, which she defined as the ability to return to a functional state instead of breaking when stressed. She described co-design as a culture shift that leverages untapped resources and works toward the collective aim of reshaping a more equitable and sustainable food culture. She also stressed the importance of evaluating the impact of design strategies after their implementation to assess their impact and, in particular, to identify any adverse consequences for marginalized communities. England pointed out that equal opportunities do not necessarily lead to equal impact, and stated that co-design can help reshape the food culture to make it more equitably beneficial and environmentally sustainable.

Examples of Use of Co-Design Principles

England shared a few examples of resources that use the design principles she had outlined. She described the Better Buying Lab at the World Resources Institute, which released a playbook to guide diners toward plant-rich dishes in food service, providing recommendations for behavior change strategies for chefs and food service workers. She also highlighted Innit, a food environment choice architecture platform that brings consumer packaged goods companies, retailers, and home appliance manufacturers together in a digital platform that shifts behavior toward transparency, collaboration, sharing, and integration across food environments and pathways. As another example she cited IDEO, a design firm working with The Rockefeller Foundation, which designed place-based, people-centered interventions in the food system, such as the redesign of hotels’ all-you-can eat culture to reduce food waste. The company is also responsible for the Food System Vision Prize, as well as OpenIDEO, a social impact platform powered by design thinking that lets anyone help design solutions to challenges across the food system. Finally, England mentioned Ikea’s in-house research and innovation design lab Space 10, which is using the company’s

global supply chain to explore more sustainable food and food environment solutions.

Questions to Guide Food Systems Co-Design

England concluded by recommending several questions to guide co-designs for food system transformation: (1) whether there is flexibility in the designs for co-designers to make changes to remain resilient; (2) who is not at the table; (3) whether new design is needed, or only slight tweaks to the old design are sufficient; and (4) who should develop the solution.

Following England’s presentation, Peters asked her for guidance on how best to bring in other people as co-designers without implying that the designer has all the answers. She responded that the design process establishes a power dynamic from the beginning regarding roles and expectations for who has the solutions. She stressed the importance of bringing the people who would benefit from the design into the process early, and stated that the role of the designer should be to facilitate and capture the conversation and increase feelings of confidence and self-efficacy among those creating the solutions.

POLICY APPROACHES TO ENABLE MULTIPLE PATHWAYS TO CHANGE

The final speaker of the workshop, Catherine Kling, Cornell University, spoke about policy approaches to enable multiple pathways to change, noting that those approaches complement the producer, supply chain, consumer, and design approaches described by prior speakers. Her presentation included three key themes: (1) economic and social incentives drive the food system; (2) economically efficient systems will often be more sustainable and resilient because they use scarce resources without waste to provide the most value; and (3) market failures, such as asymmetry or lack of information and powerful controls on prices or decisions, require policies to correct them. Kling shared her goals for food system transformation, which included affordable and nutritious diets; good farm profitability and working conditions; environmental sustainability, including reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and improved water quality, reduced air pollution and odors, and protection of wildlife habitat and biodiversity; animal welfare; and food safety.

Market Inefficiencies in the Food System

Kling described several market inefficiencies in the food system. Defining externalities as unintended side effects of market production or

consumption that impose costs on others, she stated that externalities, particularly those of public goods, provide benefits or costs for people regardless of whether they are involved in the market. As an example she cited GHG emissions, which are released unintentionally through the production of fossil fuels and cause damage around the world.

Another market inefficiency Kling described is market power, which denotes a situation in which a small number of buyers or sellers control the market and prices. She identified as still another market inefficiency lack of information about risks and benefits, such as whether a food is healthy or what risks are associated with farm labor.

Kling pointed out that each of these market inefficiencies may require a different policy solution. For example, she said, a cap and trade program can address externalities involving GHG emissions and air and water pollution; antitrust regulations can address market power inefficiencies; and education and public service tools can address education failures. Kling explained that policy can level the playing field for players across the supply chain and the entire food system. In response to a question from Peters, she reiterated that markets will not solve the problem of global warming because it is a market failure, and policy interventions, such as a worldwide cap and trade program, are needed.

Kling pointed out that markets are agnostic about fairness and equity. However, she said that while these issues are not market failures, they should be addressed through policy in the form of social safety net and poverty reduction programs and education and training. She suggested that for every problem, it is important to understand the incentive causes and identify the appropriate policy solutions.

Mississippi River Watershed Case Study

Kling spent the rest of her presentation using the example of agriculture in the Mississippi River watershed to illustrate the need for tailored policy approaches. She described the Mississippi River watershed as an area covering 40 percent of the continental United States and 57 percent of U.S. farmland, including nearly 100 million acres of corn, 84 million acres of soybeans, and 45 million acres of wheat, making it the second most productive agricultural system in the world. She added that it has more than 300 animal species and is crossed by 60 percent of migratory birds. The majority of the corn and soybeans grown in the region is used for fuel (ethanol) and animal feed, she elaborated, with only a small amount going to food, being processed into oils and sweeteners. Kling noted that this area also has high and increasing levels of harmful nitrogen and phosphorous.

Kling stated that the policy interventions needed to address the issues in this low-cost commodity market differ from those used in a local or organic

market. The environmental impact of agriculture on the region is harmful and significant, she stressed. She pointed out that overall, 10 percent of all GHG emissions are caused by agriculture, suggesting that a carbon tax or cap and trade system that compensates farmers who sequester carbon should be encouraged. Water quality in many of the rivers, streams, and lakes in the Mississippi River watershed is poor, she added, and there has been a significant reduction in wildlife habitat and biodiversity, due largely to agriculture. Kling noted that about 90 percent of the original wetlands in the United States have been lost. In addition, she pointed to a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico that is commonly referred to as “the size of the state of Connecticut,” which would have to be addressed by reducing and optimizing fertilizer use and changing farming practices. Kling referenced one study according to which a solution would require these changes to be implemented on 90 percent of the land.

According to Kling, policies to address the adverse environmental impact of the agricultural practices she had outlined include regulations to reduce and optimize fertilizer use; taxes; and requirements regarding such farming practices as use of cover crops, erosion control, protection of wetlands, and use of bioreactors. Tax revenue could be used to subsidize the desired activities, she suggested. She asserted that these policy changes would increase prices and improve the alignment of incentives in the system.

The Role of Policy

Regarding the role of policy, Kling argued that policy should address the core problem as directly as possible. Multiple problems require multiple responses, she observed, and one size does not fit all. She stated that policies level the playing field, enable supply chain management, and facilitate implementation of consumer preferences.

Peters relayed a question from an audience member about how to address the contribution of multiple sectors to adverse environmental impacts in such places as the Chesapeake Bay Basin and incentivize action. Kling replied that while each sector currently has targets for reduction, those targets are voluntary; thus, the market failure persists because the actors are not appropriately incentivized to make the necessary changes. She suggested that policies would be needed to implement incentives for change.

PANEL DISCUSSION

Following the presentations summarized above, Peters facilitated a discussion with Prabhala, Caradec, England, and Kling.

Coordinated Versus Individual Actions

Peters began by asking the panelists which food system transformations are most important for coordinated action, rather than isolated actions by individual companies or governments. Caradec replied that actions by both coalitions and individual companies are needed, referencing Danone’s work at both levels.

Both Prabhala and Kling suggested that when it is difficult for an individual company or farmer to internalize the external costs of action, a coalition or multisector collaboration may be needed. In contrast, when the entities that implement a strategy will realize returns on that action, external actors are not necessary. Prabhala gave as an example that replenishing water basins is expensive, so most companies would be unable to afford to take that action without harming their economic model. In this situation, he suggested, an intervention forcing all companies to internalize these costs equally might be needed. In contrast, Prabhala observed, more than half of 25 possible interventions to reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture pay for themselves over a period of time, meaning that companies or farmers that implement them will experience a financial benefit. In these situations, he stated, the companies can effectively internalize the costs of action without having to rely on external actors. Kling added that individual farmers and growers can afford to make costly changes only when they are all required to do so and everyone’s costs therefore increase simultaneously, leading to higher prices being passed through the chain.

Kling also highlighted how states have established regional coalitions to address GHG emissions given the lack of action at the national level, noting that government entities, nongovernmental organizations, and private businesses can all form coalitions. Prabhala pointed out that when collective action is required, an entity is needed to facilitate and organize the stakeholders.

The Role of and Impact on Small-Scale Farmers

Peters asked for input on the role of small-scale farmers in advocating for agroecology and in supporting and leveraging the use of local and Indigenous knowledge in efforts to transform the food system. Caradec responded that in the United States, Danone works with both small-scale farmers and larger farms, while outside the United States, many of the company’s suppliers are smallholder farmers organized into cooperatives. Prabhala pointed out that solutions can be scaled in different ways, including an individual firm integrating components, replicating what has worked in a different place, and “formalizing the informal” by compiling effective subscales. He suggested that different models will work in different settings,

and that the roles of policy and financing mechanisms differ. Prabhala observed that each model has its own pros and cons and unique set of challenges.

England added that allowing smallholder farmers to keep doing business without forcing them to scale makes them more resilient to a crisis. She suggested asking the question of why small farmers need to scale and whether they might be better off remaining small and nimble. Peters pointed out, however, that in many industrialized countries, farm size and scale are increasing, and farms may have to scale to stay viable. Prabhala agreed, pointing out that even in such places as Africa where there are many smallholder farmers, scaling is necessary for entities too small to implement interventions. He argued that technology and broader economic development can help support transformations in emerging markets that drive productive improvements among small farmers.

Kling observed that in the United States, the majority of the farmland in the Mississippi River watershed is farmed by large-scale producers that have crop insurance and are heavily subsidized by the federal government. She explained that while the number of U.S. farmers declined substantially in the past century, the same amount of land is still being farmed, meaning that farms have grown in scale. She added that many of these farmers also have off-farm income and are successful business owners.

Equity and Inclusion

Relaying a question from an audience member, Peters asked England how to continue the momentum regarding equity and inclusion within agriculture and environmental preservation. She responded that while “equity” and “inclusion” are frequently used as buzzwords, their actual practice is difficult, and food system transformation will require many years. She reiterated the importance of considering who is not at the table and why not, even if the impact of a proposed change appears to be small. She also suggested examining current practices and the reasons behind them before making a change.

Consumer Behavior Change and the Role of Public Policy

Peters asked about the role of behavior change in supporting the kind of dietary change that leads to food system transformation, noting that he sees benefit in better engaging behavior change specialists, such as registered dietitians, in transformation efforts. Prabhala asserted that the context or environment in which people eat greatly influences their food choices. He pointed to the increased focus on precision nutrition, which would allow for the provision of personalized advice based on individual genetics.

Caradec explained that Danone North America is using public policy to push for the adoption of a flexitarian diet, which would include increased plant-based nutrition and less sugar. He also pointed out that there are many different types of consumers, and companies need to offer products that meet their varied expectations. According to England, because food is one of the most intimate choices that people make on a daily basis, influencing behavior change requires understanding the roles of environments, emotions, and psychology in individual food choices.

The panelists had a robust conversation about the role of public policy in supporting behavior change. Kling argued that the role of policy in supporting behavior change is to provide people with accurate information and education that will enable them to make their own choices, but it is not the government’s job to change people’s behavior through taxes or other interventions. Caradec expressed the view that public policies, such as nutrition standards for school meals, the WIC program, and others aligned with Danone’s reduction of sugar in its yogurts for children, can also influence changes in the marketplace. He stated that Danone made changes to achieve that reduction but did not announce the changes until after they had been implemented so as not to adversely impact people’s perceptions of the yogurt’s taste. He urged that other food manufacturers take such action to improve their product portfolios.

Prabhala argued that people often make poor choices because of a lack of information or exposure to misinformation. He suggested that policy makers use regulation to support smarter choices, such as through labeling. Caradec stated that the United States already has an excellent Nutrition Facts label. England noted, however, that consumption decisions are shaped by the food environment and food policies, such as whether a food is available in schools or where it is placed on a grocery store shelf. She pointed out that just because the Nutrition Facts label exists does not mean that people use it to make decisions; when busy, stressed, or distracted, she asserted, people often fall back on whatever meets their emotional needs.

England suggested further that punitive policies, such as soda taxes, may be appropriate when balanced with positive incentives. Prabhala agreed on the need for mechanisms that penalize people for behaving in ways that impose costs on society, such as health care costs borne by government programs. Kling expressed opposition to soda taxes because, she argued, people should be educated and allowed to make their own decisions. She added that in a fully functioning market, health insurance companies would offer lower premiums for people who eat well or have a healthy body weight. Prabhala illustrated this idea by describing the pilot program of an insurance company in South Africa that provides incentives for healthy behaviors, such as purchasing produce or being physically active.

Given the connection between good nutrition and health outcomes, Peters asked whether efforts to transform the health and agriculture systems should be undertaken in parallel. Prabhala pointed to the need for better communication between policy makers in health and in agriculture, noting that cross-functional policy working groups have been established in some countries. He suggested further that changes in consumer choices will influence decisions on agricultural production in the long term. Prabhala referenced the fact that 80 percent of U.S. agricultural production is for soybeans, wheat, rice, and corn, and argued that increased production diversity is necessary to support achievement of the dietary diversity needed for improved health.

Enough from Less

Peters concluded by referencing a comment made by Porter in an earlier session (see Chapter 4) about the need to shift from “getting more from less to getting enough from less,” and asked how to define what is “enough.” England stated that there is already more than enough food to feed everyone in the world; the problem is with equitable distribution, as a great deal of food is wasted. Caradec pointed out, however, that while there are enough calories for everyone, the foods that are consumed, even in the United States, are not the most nutrient dense. Finally, Prabhala pointed to the frequent trade-offs that must be made between farm productivity and other outcomes, such as environmental impact, but suggested that technology and innovation can help address these challenges.

This page intentionally left blank.