David Acosta, M.D., FAAFP, chief diversity and inclusion officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), reviewed the historical trend of African American/Black students in medicine, engineering, and the sciences; analyzed the impact of anti-affirmative action laws and other barriers on diversifying the healthcare and science workforce; reviewed the historical trend of African American/Black faculty representation in medicine, engineering, and the sciences; and described the manifestations of structural and institutional racism in academic health science centers and the impact on medical students, residents, and faculty.1

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Reflecting on the earlier presentations, Dr. Acosta stressed the need to understand history in order to move forward. It is important to be proactive in telling this history. He noted many medical educators and diversity officers do not have in-depth knowledge about the Flexner Report and, more broadly, the long-term impact of the U.S. Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson case that provided the legal justification for segregation.2 Abraham Flexner, he said, “essentially codified the two Americas in his plans for improving medical education for U.S. physicians.” A two-page chapter of the report entitled “The Medical Education of the Negro” stated that this education was to promote “the limited education of the African American doctor as a service to his own race” and for the purpose of keeping whites from the spread of disease among African Americans. Flexner stipulated that medical schools had to be connected with universities with sufficient endowments and hospitals. This requirement was a severe challenge for most medical schools that taught African Americans at the time, which Flexner termed had good intentions but were “make believe” institutions. Five of the seven existing schools closed.

Universities, including medical schools, did not have to comply with desegregating their institutions until after Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1968, according to Dr. Acosta, 130 African Americans graduated from all U.S. medical schools. At that time, the American Medical Association (AMA) and AAMC joined to say that medical schools should have as a goal to expand the enrollment to a

___________________

1 Dr. Acosta explained that his data use both “Black” and “African American” to account for students both born in and outside the United States.

2 For more background, he suggested Steinecke and Terrell (2010).

level that permits all qualified applicants, although did not specifically refer to Black students. That same year, AAMC encouraged member medical schools to collect enrollment information by race and ethnicity, and, in 1969, established an Office of Minority Affairs. Until 1988, however, the office was embedded in the organization’s Student Affairs Division and led by a non-physician. In 1988, AAMC created the Division of Minority Health Education and Prevention and hired its first vice president to lead diversity work, Herbert Nickens, M.D.

As Dr. Acosta transitioned to a discussion about application and enrollment figures, he commented, “Do not forget the history when you look at where we are today.”

MEDICAL SCHOOL ENROLLMENT

Dr. Acosta first presented data related to medical school application and matriculation rates from 1980 to 2018.

Medical School Applications

In 1980, according to AAMC data, 2,507 Black or African American students applied to medical school, 4,344 applied in 2016, and 4,438 in 2018. He characterized this as a small increase numerically and percentage-wise, going from 7 percent of applicants to 8.2 percent in 2016 and 8.3 percent in 2018. He also called attention to the total number of applicants of all races at those different points in time, which increased from 36,083 in 1980 to 53,042 in 2016, with a slight dip to 52,277 in 2018 (Table 5-1).

Dr. Acosta cautioned the audience to look carefully at how data are compiled and reported. For instance, some AAMC reports show that Blacks and African Americans applicants represented 9.8 percent of the total in 2018–2019, rather than the 8.3 percent mentioned above. He attributed the larger number to how students of combined races or ethnicities are asked to fill out the American Medical College Application Service (AMCAS) application.

In addition to overall historical trends, Dr. Acosta said it is important to look at what he termed the influencers and detractors that affected application numbers. On a positive note, he singled out several pipeline, funding, and other initiatives. They included the Minority Medical Education Program (MMEP), started in 1989 by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

TABLE 5-1 Number and Percentage of U.S. Medical School Applicants in 1980 and 2016 by Race or Ethnicity

| 1980 | 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or Ethnicity | Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 156 | 0.4 | 127 | 0.2 |

| Asian | 1,643 | 4.6 | 10,906 | 20.6 |

| Black or African American | 2,507 | 7.0 | 4,344 | 8.2 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,764 | 5.0 | 3,300 | 6.2 |

| White | 29,256 | 81.1 | 25,544 | 48.2 |

| Total | 36,083a | 53,042b | ||

a Total includes 757 (2.1% of applicants) unknown and non-U.S. citizens and nonpermanent residents not included in the analysis

b Total includes 8,821 (16.6% of applicants) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiple-race, other, unknown, and non-U.S. citizens and nonpermanent residents not included in the analysis.

SOURCE: David Acosta, Workshop Presentation, April 13, 2020, from AAMC Data Warehouse: Applicant Matriculant File, archived January 2004.

(RWJF); Project 3000 by 2000, launched in 1991 by AAMC; and the Health Professions Partnership Initiative, launched by RWJF and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation in 1996 and 1998 to foster more involvement by medical schools in their local school communities to expand opportunities. In addition, the AAMC’s Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) issued two standards during this time: the LCME MS-8 in 2002 and the LCME IS-16 in 2009. This latter standard, Dr. Acosta said, strengthened the wording from a “you should” to a “you must” related to student and faculty diversity. According to Dr. Acosta, slight increases in applications by African Americans are shown from 1990 to 1995, then a downward trend from 1995 to 2005, then another slight increase after passage of the LCME IS-16. He also commented that Asian Americans seemed to benefit the most from these programs in terms of increases in applications.

Barriers during this time period included anti-affirmative action laws, beginning with Proposition 209 in California in 1996. Other states that have passed anti-affirmative action laws include Texas (1996), Washington State (1998), Florida (1999, by Executive Order), Michigan (2006), Nebraska (2008), Arizona (2010), Oklahoma (2012), New Hampshire (also 2012), and Idaho (2020). In 2019, a long-standing case involving

admission policies at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center was resolved.3 Dr. Acosta emphasized that affirmative action and actions against it are “very much alive,” but a number of resources to help institutions document their admissions processes, including publications from AAMC (AAMC, 2014), the College Board and Education Counsel (Coleman and Keith, 2018), and Urban Universities for Health (2014). He also noted that the amicus briefs from the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court case Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin provides useful summaries of issues involved with affirmative action in admissions.4

Medical School Matriculation

In 1980, 999 Black and African American students matriculated in U.S. medical schools, and that number increased to just more than 1,400 in 2016 and 1,540 in 2018. The number of total seats rose from 16,587 in 1980 to 21,030 in 2015 (Table 5-2), and to 21,622 in 2018. Dr. Acosta characterized the figures:

The percentage has gone from 6.0 percent in 1980 to 7.1 percent in 2016. It is amazing over that span of years, how low a number that is, particularly keeping in mind the total number of seats.

Dr. Acosta again pointed out that this number includes some people with a combination of races, as well as people born outside of the United States. Disaggregating, he pointed out, shows that 284 Black, U.S.-born males were enrolled in medical schools out of more than 21,000 seats.5

Looking at graduation rates among underrepresented minorities between 2001 and 2002, Blacks and African Americans had the lowest 4-year rate at 69.6 percent, although the rate increased after 5 and 6 years to a comparable level with other groups. He stated,

Questions remain. We need further research to find out why the rate is so low after 4 years. Instead of going by anecdotal experience, we need the research and the data to home in what we can possibly highlight and change moving forward.

___________________

3 For background, see Coleman and Keith (2019).

4 A compilation of the documentation related to this case can be found at https://legal.utexas.edu/scotus-2015 [Accessed May 14, 2020].

5 For more background on Black males in medicine, see NASEM (2018).

TABLE 5-2 Number and Percentage of U.S. Medical School Matriculants in 1980 and 2016 by Race or Ethnicity

| 1980 | 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or Ethnicity | Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 63 | 0.4 | 54 | 0.3 |

| Asian | 679 | 4.0 | 4,475 | 21.3 |

| Black or African American | 999 | 6.0 | 1,497 | 7.1 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 807 | 4.9 | 1,335 | 6.3 |

| White | 13,884 | 83.7 | 10,828 | 51.5 |

| Total | 16,587a | 21,030b | ||

a Total includes 155 (9% of matriculants) unknown and non-U.S. citizens and nonpermanent residents not included in the analysis.

b Total includes 2,841 (13.5% of matriculants) Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiple-race, other, unknown, and non-U.S. citizens and nonpermanent residents not included in the analysis.

SOURCE: David Acosta, Workshop Presentation, April 13, 2020, from AAMC Data Warehouse: Applicant Matriculant File as of August 22, 2017.

GRADUATE SCHOOL ENROLLMENT IN SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING

Turning to science and engineering disciplines, Dr. Acosta said graduate school enrollment mirrors the situation in medical schools. According to data compiled by the National Center for Science & Engineering Statistics of the National Society Foundation, the number of Blacks or African Americans earning science or engineering bachelor’s degrees as a percentage of the overall degrees granted has been static since 1996, with the lowest numbers in engineering and the highest in psychology, social sciences, and computer sciences. The anti-affirmative action measures discussed above also had an effect in science and engineering fields. Overall, in 2016, about 4.9 percent of all science and engineering graduate students were Black or African American (Table 5-3). Disaggregated by sex, 6.7 percent of the total pool were African American/Black females and 3.6 percent are African American/Black males.

MEDICAL SCHOOL FACULTY REPRESENTATION

Medical school faculty are predominantly male, as Dr. Acosta showed with data compiled by AAMC. In 2010, there were 52,300 women faculty

TABLE 5-3 U.S. Science and Engineering Graduate Students by Field, Race, and Ethnicity, 2016

| Total | African American/Black | Hispanic | American Indian/Alaska Native | Asian | White |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 620,489 | 30,600 (4.9%) |

39,578 | 1,860 | 35,674 | 237,563 |

| Engineering | |||||

| 168,443 | 3,710 (2.2%) |

6,966 | 245 | 9,920 | 45,622 |

| Sciences | |||||

| 452,046 | 26,890 (6.0%) |

32,616 | 1,615 | 25,772 | 191,194 |

SOURCE: David Acosta, Workshop Presentation, April 13, 2020, from the National Center for Science & Engineering Statistics, NSF 19-304.

in U.S. medical schools and 92,047 males. In 2019, there were more female faculty but a gender gap of about 27,600 positions in academic medicine remained.

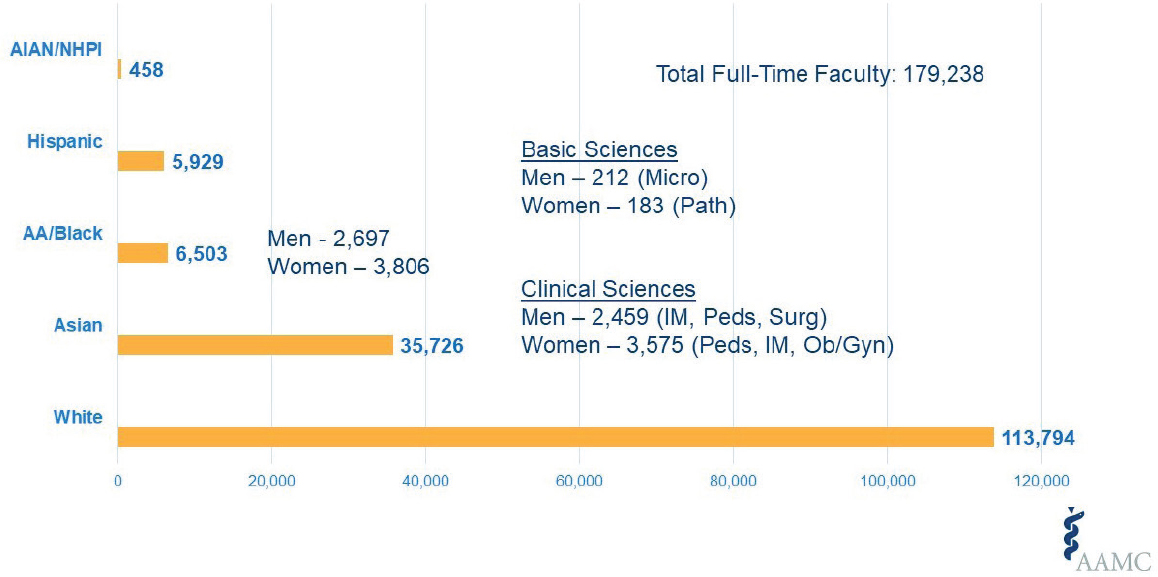

By race and ethnicity, among full-time faculty, there were 113,794 whites; 35,726 Asian; 6,503 African American/Black; 5,929 Hispanic; and 458 American Indian/Alaska Native/Pacific Islander. There were more African American women than African American men: 3,806 full-time female faculty and 2,697 full-time male faculty. Men and women are about at par in the basic sciences, but the larger proportion of women come in the clinical sciences, which have the largest number of medical faculty positions overall. Most of the women are teaching, in order of frequency, pediatrics, internal medicine, and obstetrics/gynecology; men are most commonly in internal medicine, pediatrics, and surgery (Figure 5-1).

Looking at all underrepresented minority science and engineering Ph.Ds. employed in academia, Dr. Acosta characterized these numbers as “lackluster, with the needle barely moved along the way.” Percentage-wise, African American and Black women filled 4.7 percent of full-time positions in 2003, and had slightly declined to 4.6 percent in 2013. African American and Black men filled 2.9 percent of the full-time faculty positions in 2003, a percentage that slightly increased to 3.3 percent in 2013.

SOURCE: David Acosta, Workshop Presentation, April 13, 2020, based on AAMC data.

MANIFESTATIONS OF STRUCTURAL AND INSTITUTIONAL RACISM

With these data in mind, Dr. Acosta shared a cartoon in which a white man and African American woman are “racing” toward a finish line. The man’s route has a few hurdles along the way; the woman’s is filled with barbed wire, walls, and the like. Quoting a former senior academic editor at the American Association of Colleges and Universities, “Our institutional policies and practices, infrastructure, governance, unspoken rules, and expectations have perpetuated a double standard for specific groups.” He added that intersectionality also plays a role and sometimes learners, faculty, and staff are confronting triple or even quadruple standards.

Several studies have identified challenges faced by medical students and residents from historically excluded and underrepresented groups in STEMM (HEUGS), Dr. Acosta said, including difficulties in acculturation to the culture of medicine, mistreatment, microaggressions, isolation and marginalization, racial biases, prejudice and discrimination, and the imposter syndrome. Dr. Acosta stated:

We haven’t dealt successfully from a systemic standpoint with these challenges—looking at the infrastructure, the policies, the practices that have perpetuated these challenges, and I think those are going to have to be addressed as we begin to find solutions that are systems-based. We need to move beyond blaming the typical things we tend to blame; I think it’s a higher order now that we have to begin looking at.

Each year medical students fill out an AAMC survey about their medical school experience. About 40 percent of those who responded to the most recent survey reported personal experience with harassment or treatment that included racial discrimination.6 Other studies have similar findings. A 2011 systematic review of the literature showed 59.4 percent had experienced at least one form of harassment or discrimination during their training, and about 26 percent indicated they had at least one experience with racial discrimination (Fnais et al., 2014). Medical school faculty from HEUGS reported a number of challenges, including difficulties in acculturation, racial battle fatigue, sexual harassment, and inequity in salaries and promotion.

___________________

6 See findings of the AAMC 2019 Graduation Questionnaire at https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/2018gqallschoolssummaryreport.pdf [Accessed May 14, 2020].

The impacts, he said, may include poor emotional and mental health outcomes, post-traumatic stress disorder, and burnout. Burnout is an issue for many medical faculty members, as it is for physicians (Dandar, Grigsby, and Bunton, 2019). The percentages of women (of all races and ethnicities) who reported they were burning out or were already burnt out are higher than for men.

Dr. Acosta concluded that the numbers and percentages of African American and Black students applying to medical school and science and engineering graduate schools have remained relatively flat over the past 30 to 40 years, despite multiple efforts to address the problem. Anti-affirmative action laws have impacted these efforts to accelerate the enrollment. The number of African American and Black matriculants and faculty have also remained relatively flat, and it is important to disaggregate the data and interpret them correctly. He also urged more research to learn about graduation rates, students who take the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) but do not apply to medical school, where African American physicians practice and for whom they provide patient care, and the disciplines in which enrollment is particularly low, such as engineering. Finally, it is important to look carefully at institutional environments. Racial tension, biases, and discrimination are on the rise and are impacting learners and faculty, he concluded.

DISCUSSION

In response to a question from a participant about any differences in graduation rates between historically Black compared to predominantly white medical schools, Dr. Acosta said that AAMC and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have conducted a survey to focus on attrition in residency programs. They are looking upstream to see the institutions from which the residents come, which might help answer this question. Findings are expected in the next 3 to 6 months.

The issue of standardized tests and their role in medical school admissions and the residency programs was raised. Clarifying that he was speaking as an individual and not for AAMC, he suggested that when the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) becomes pass-fail, it may level the playing field; for a long time, the “Step 1” scores have functioned more as a screening-out than a screening-in process. He suggested this change may open up a discussion on how to look at a student’s distance traveled and other attributes, as well as relying less on MCAT scores for medical school admission. Osteopathic medicine moved away from the MCAT for admis-

sions in 2020 because of COVID-19, a decision that may provide an example for content experts to study and discuss, he suggested. He also called attention to the students who do not “match” a residency program because of test scores, noting he himself did not pass Step 1 of the USMLE until his third attempt. “I worry about the students who get lost in the system but should remain because they have such talent,” he said. “The good news is that it starts with conscious awareness of a problem to get to a solution.”

Dr. Jones further suggested finding a way to follow up with individuals to learn and communicate about the lost talent that results. “I think of all the people who took the MCAT but never applied to med school,” she said. “We act as if that is all right, but we don’t understand the magnitude of the loss in terms of lost talent.” Dr. Acosta agreed this could be an important area of research. He added it is important to communicate more about the accomplishments of students who overcame significant adversity and succeeded.

Related to admissions, Dr. Acosta pointed to the need to look at members of admissions committees. “Their performance needs to be evaluated,” he asserted. “How did they screen in or screen out students? What were their scores? How many did they advocate for?” There may be a need for term limits or not retaining members who cannot be trained in this broader view. He said that about 25 percent of admissions committees include community members. Some states have more control over universities than others in setting the bar and limiting entry for underrepresented minorities. There is a need to identify and be vocal about those states and state legislatures, Dr. Acosta said.

Referring to Dr. Acosta’s data related to application and enrollment numbers, a participant asked why bridge programs seem not to have a large impact on the numbers. Dr. Acosta replied,

The problem is not the pipeline, the problem is who is in control to get past the gate into med schools…. We have a body of people [medical schools] who control what our workforce looks like. We have the data because people ask for the data, we’ve created pipeline programs because people have asked for them to meet accreditation, we have donations from philanthropic organizations who believe in and see the value in it. The reality is we have done a lot of this work and still this [disparity] prevails…. It’s about essentially there are laws, there are policies, there are practices, there are values and customs and beliefs specifically not to upset the status quo.

He also noted the need for data about where students in pipeline programs are accepted; anecdotally, he commented that many schools have excellent pipeline programs but the students in them have to go elsewhere for admission to medical school. Quantitative data are also needed to validate whether increasing the number of African American faculty would be reflected in a more diverse talent pool. Expanding the number of underrepresented minorities in leadership positions might also help, he added. To that end, AAMC conducts several programs, including minority faculty leadership summits for early career and mid-career faculty. For the past 5 years, a health executive diversity certification program has been offered for assistant and associate deans, as well as current and potential chief diversity officers.

Dr. Acosta acknowledged that different states have different demographic compositions in terms of who makes up that state’s minorities or disadvantaged groups. He urged, “In defining diversity for your institution, define it as you will, but there’s an important question you have to answer, too. How is your institution addressing the national crisis based on the data we have for all population groups?”

REFERENCES

Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). 2014. Roadmap to Diversity and Educational Excellence: Key Legal and Educational Policy Foundations for Medical School, Second Edition. Prepared for AAMC by A. L. Coleman, K. E. Lipper, T. E. Taylor, and S. R. Palmer. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/192.

Coleman, A., and J. L. Keith. 2018. Understanding Holistic Review in Higher Education Admissions: Guiding Principles and Model Illustrations. Prepared for College Board and Education Counsel. https://professionals.collegeboard.org/pdf/understanding-holistic-review-he-admissions.pdf.

Coleman, A., and J. L. Keith. 2019. Race in admissions in the wake of the Texas Tech resolution. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/insights/race-admissions-wake-texas-tech-resolution.

Dandar, V., R. K. Grigsby, and S. Bunton. 2019. Burnout among faculty in academic medicine. Analysis in Brief, 19(1), 1–2.

Fnais, N., C. Soobiah, M. H. Chen, E. Lillie, et al. 2014. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 89(5), 817–827.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). 2018. An American Crisis: The Growing Absence of Black Men in Medicine and Science: Proceedings of a Joint Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25130/an-american-crisis-the-growing-absence-of-black-men-in.

Steinecke, A., and C. Terrell. 2010. Progress for whose future? The impact of the Flexner Report on medical education for racial and ethnic minority physicians in the United States. Academic Medicine, 85, 236–245.

Urban Universities for Health. 2014. Holistic Admissions in the Health Professions: Findings from a National Survey. https://urbanuniversitiesforhealth.org/media/documents/Holistic_Admissions_in_the_Health_Professions_final.pdf.

This page intentionally left blank.