2

The Land and the People—Ecological, Historical, and Cultural Antecedents

In the last 20 years, more than $2 billion has been invested in the New York City Watershed Protection Program, and many new partnerships, programs and approaches have emerged. Although the Watershed Protection Program has matured and is frequently cited as an international success story, persistent challenges and controversies date back to the negotiation of the 1997 Memorandum of Agreement (MOA). In some cases, they date back to the initial development of the Catskill and Delaware systems and sudden intersection of two worlds: a powerful, burgeoning city and a long-settled rural landscape with well-established communities (Evers, 1982; Galusha, 2016; Soll, 2013; Steuding, 1985).

Participants and decision-makers in any source water protection program could benefit from a shared understanding of the ecological, historical, and cultural antecedents of current conditions and future challenges and opportunities. A thorough understanding of historical precedents and diverse (sometimes diametrically opposed) perspectives is especially important for managers, policy makers, principal stakeholders, and political leaders, as well as for the public at large. Particularly in the case of New York City, the long-term success of watershed management is dependent upon shared values, mutually beneficial goals and objectives, and equitable distribution of costs and benefits (Warne, 2018). To that end, Chapters 2 and 3 build upon NRC (2000) and other recent works (e.g., Duerden, 2007, Galusha, 2016, Soll, 2013) by summarizing the information needed to adequately address the origins of complex issues that have emerged since the Watershed Protection Program began in the late-1990s. A summary and synthesis—linking the Catskills region and New York City—is vitally important to establish common ground for the next phase of the Watershed Protection Program, especially during the leadership transitions that will occur during the next decade.

GEOLOGY, SOILS, AND VEGETATION

The eastern extent of the Catskill Mountain region is clearly defined by the Hudson River Escarpment, rising about 500 meters, 8 to 10 km away from the river. The north-south extent of the region is reasonably distinct. The region extends from the escarpment, through the highest peaks (1,000 to 1,275 meters) in the Esopus Creek and Schoharie Creek watersheds, and tapers off to the west toward the Delaware River valley, Susquehanna River valley, and the Finger Lakes region (Figure 2-1).

A Devonian Age delta with horizontal layers of sandstone, siltstone, shale, and conglomerate bedrock is the geologic substrate of the region. When the deciduous trees on the mountainsides are bare, these ancient bedding planes can be seen in the slope profiles and the horizontal orientation of rock outcrops. This geologic structure is also evident in road cuts and in rock outcrops along most trails. Eons of erosion have dissected the plateau with well-defined stream valleys and long, relatively steep slopes. The massive ice sheets of the Pleistocene rounded the summits, deposited a thin layer of coarse-textured, highly permeable glacial till on

the hillsides, and filled the narrow valleys with glacial sand and gravel deposits. Some streambeds have exposed layers of lacustrine clay. This material and other fine sediment is mobilized during stormflow events. As discussed in Chapter 6, the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYC DEP) stream assessments have identified relatively limited areas on two tributaries of Esopus Creek that generate a large proportion of the total suspended solids (turbidity) entering the Ashokan Reservoir.

Geologic and soil characteristics directly influence pathways and rates of water flow. The relatively impermeable horizontal bedrock layers limit vertical flow to bedrock fractures. In contrast, the glacial till conveys large volumes of shallow subsurface flow to stream valleys—ranging from the smallest ephemeral streams near the ridgelines to the largest creeks in the major valleys. The saturated source area is dynamic—expanding rapidly during rain, snowmelt, and rain-on-snow events. These saturated source areas recede or contract at rates that are proportional to the size and duration of the rain or snowmelt event and the site-specific soil and landform characteristics. The high drainage density and dendritic or trellised configuration of headwater streams, larger streams, and major creeks efficiently transmit water from the most remote headwater areas to New York City’s reservoir system.

Water yield and quality are also influenced by soil properties. Most soils are thin (20 to 130 cm), stony, sandy loams with a high infiltration capacity and permeability (hydraulic conductivity) and limited plant available water (water-holding capacity). Thicker, fine-textured soils (e.g., silt loams) can occur on gentle slopes, broader floodplains or natural terraces. They are the most productive, accessible and valuable land for agricultural uses.

THE FOREST

A forest’s species composition, age class distribution, vertical structure, and landscape patterns are a long-term, dynamic reflection of climate, soil and site characteristics, and natural and anthropogenic (human-caused) disturbances. Acute anthropogenic disturbance is often the dominant driver of forest change; this is certainly the case in the Catskills (Kudish, 2000). Later sections describe the temporal sequence, influence and cumulative effects of human use in detail.

Only about 6 percent (24,550 ha) of the 405,000-hectare watershed area has primary forest areas (“first growth” or “old growth”) that have not been altered by human activities (Kudish, 2000:82-86). Just over half of this primary forest area occurs in two large blocks: Mill Brook Ridge-Big Indian (6,700 ha) and Slide-Panther-Peekamoose (6,400 ha). The remaining patches are scattered among 35 other areas (13 of which are less than 25 ha). Virtually all of the primary forest areas are draped over mountaintops, above an average elevation of ~900 meters (2,900 feet) (Kudish, 2000). They are stands of balsam fir, red spruce, paper birch, mountain ash and other relatively small boreal tree species——growing on very thin, stony soil, and subject to frequent damage from high winds, ice and snow, and summer droughts.

An interrelated set of site characteristics (e.g., soil properties and water availability, slope gradient, landform, aspect, elevation, exposure to wind) have a foundational influence on forest composition. This is apparent in three elevational zones: (1) mountaintops and ridgelines, (2) mid-slope areas (most of the watershed), and (3) valleys and floodplains. The high-elevation forests are remnant stands of boreal- and boreal-transition species. Mid-slope forests are typically northern hardwoods: American beech, sugar maple, and yellow birch, with red maple, white ash, and hophornbeam present in smaller numbers. American beech is the most common species on many sites, by dint of being less desirable for commercial uses and its prolific sprouting ability. Eastern hemlock trees scattered through mid-slope and lower-slope sites are a very small remnant of the large proportion of the Catskills forest they once comprised. This change in forest composition, especially the shift from evergreen to deciduous species, is likely to have changed nutrient cycling rates and the loading of natural organic matter (NOM) to streams. Differences in foliar characteristics and chemistry can substantially alter decomposition rates, soil chemistry and microbial populations, and the pH of streams (Likens et al., 1995; Lovett and Rueth, 1999; Lovett et al., 2002).

Lower slopes and valleys transition to central hardwood species (several species of oak and hickory, and Eastern white pine). Before it was extirpated by a fungal blight in the early-1900s, American chestnut would have been a common species at lower elevations and substantial component of mid-slope forests. Species such as red maple and red oak now occupy its niche. Floodplain forests are limited in areal extent by the topography of the Catskills but, where present, contain species such as American sycamore, silver maple, cottonwood, and willows. American elm was lost from floodplain and low-elevation forests after the accidental introduction of Dutch elm disease in the early 1900s.

The current composition and structure of forests in the Catskills are the product of a complex mix of natural and human disturbances. This process will continue as invasive insects and diseases, air quality changes, climate change (i.e., precipitation patterns, air temperature and evapotranspiration regimes, extreme weather events, etc.), and human use (ranging from intensive utilization to complete protection) combine in predictable and unpredictable ways. The history, character and condition of the Catskills forest demonstrates the remarkable resilience of this ecosystem—the living filter for Catskill Mountain communities and the NYC water supply system. The human activities that shaped this landscape are summarized below.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE AND THE COLONIAL ERA

For thousands of years, what came to be called the Kaatskills by Dutch colonists was the mountainous region adjacent to the core homelands of several major cultural groups: the Haudenosaunee (“People of the Longhouse”) to the West, the Mohicans to the East, and the Wabanakis and Hurons to the North (Hagan, 2013). As Schneider (1997) observed, “the Haudenosaunee used their vast forest holdings as a range from which to draw protein to supplement

their crops [the Three Sisters: maize, beans, and squash], the way a fishing village might use the sea.” This analogy would be equally applicable to the neighboring cultural groups. Schneider goes on to note, as have many other authors (e.g., Berkes, 2012; Hughes, 1996), that indigenous people actively managed forest vegetation and wildlife habitat (e.g., using frequent burning to foster the growth of grasses, berries, and other food resources) and wildlife populations (e.g., hunting deer during the fall breeding season and avoiding the harvest of does whenever possible). Hence, the Catskill Mountain region was never a “pristine wilderness” untouched by human activity. That said, the use of land and resources by Indigenous people was much less intensive and more ecologically sound than what would follow.

The fur trade was the earliest interaction between Indigenous people and European explorers. Trading between Indigenous people and Henry Hudson and the crew of the Half Moon took place during their first trip in 1609 up the North [now “Hudson”] River. This small-scale, ad hoc trading presaged a formal, well-organized, and lucrative trans-Atlantic network that connected the New World with the Old World within a few decades. Major fur trading posts were quickly established by the Dutch at Wiltwyck (now Kingston), Fort Orange (now Albany), and, the largest of all, in New Amsterdam (now New York City). A large quantity of diverse goods came from all over Europe, and later, the United Kingdom, to annually restock the major posts and the inventories of traders who traveled to the interior villages and gathering places. The ships returned to the major fur markets of Europe laden with “soft gold.”

Within a few generations, the fur trade and interactions between Indigenous people and colonists ran their typical course. Disease exacted a gruesome toll on indigenous communities; 80 to 90 percent mortality rates were not uncommon. There was a very rapid transition from an age-old sustenance economy with continental trade routes to a volatile market-based economy with global connections to dramatically different cultures. Dependence on European tools and weapons, alcohol and tobacco addiction, and the subsequent loss of traditional ecological knowledge and established lifeways quickly weakened native communities. Fur-bearing wildlife populations were decimated—disrupting food webs and forest ecosystems.

In extremis, Indigenous people mounted raids on isolated farms and small villages. These last-ditch efforts to remove colonists generated a rapid and brutally effective response by the Dutch authorities and militias (and later, by the English). Although the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy1 was an important British ally on the winning side of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), their subsequent alliance with Great Britain on the losing side of the American Revolution (1776-1783) greatly diminished their autonomy, land base, and future prospects in America. The net effect of this depopulation of the Catskills was the vigorous regrowth of the forest understory in the absence of Indigenous people’s frequent and skillful use of fire.

The population of the New Netherland colony grew slowly after its establishment in 1624 until about 1655 (a total of about 2,000 people with ~1,500 in New Amsterdam). It grew rapidly thereafter, reaching 9,000 people in 1664 (with about 2,000 people in New Amsterdam). As an international port city, New Amsterdam, though dominated by the Dutch, included many other ethnic groups (Shorto, 2005). In 1634, a Jesuit missionary noted that 18 languages could be heard among the few hundred residents. This cultural and ethnic diversity increased as more groups arrived in the early 1700s and traveled up the Hudson to establish or augment earlier communities. These “New Netherland” cultural foundations of the New York metropolitan area influence values, attitudes, means, and methods to this day (Woodward, 2011). In contrast, the dominant “Yankeedom” cultural foundations and perspectives of people and communities in the Catskills region are derived from an interrelated, yet largely independent and distinct, history (Box 2-1).

The Hardenbergh Patent

When the last Director-General, Peter Stuyvesant, surrendered New Amsterdam and New Netherland to the commander of a British fleet and invasion force in 1664, both the city and colony were renamed New York at the stroke of a royal pen. The King’s brother, the Duke of York, became the new landlord and ushered in another period of rapid and lasting change. For example, a dubious land “purchase” of nearly 2 million acres by Johannes Hardenbergh in what are now parts of Ulster, Greene, Delaware, Orange, and Sullivan counties,

___________________

1 See, e.g., https://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com.

was confirmed by the Royal Governor of New York and, ultimately, by Queen Anne. The subsequent “Great Lot” subdivision, rough initial surveys across steep terrain, and the legal complexities of deeds and bequests still influence land titles and transactions in the region. Other legal and political controversies generated by the Hardenbergh Patent and conflicting land claims through much of the 1700s had the effect of delaying settlement of the Catskills for several generations (~50 years). In contrast, the City of New York, the Hudson Valley and other communities began to grow rapidly—gaining population and political power—during the first half of the 18th century.

EARLY EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

Northern Catskills and the Esopus and Schoharie Valleys

Agrarian settlement of the Esopus and Schoharie valleys by Europeans in the northeastern Catskills began shortly after the end of the American Revolution. Most emigrated from Connecticut in search of larger, less expensive, and potentially more productive home-steads. Other families came from the adjacent Hudson River valley. Of necessity, early settlement began with the slow task of forest clearing (about 2 to 3 acres [1 hectare] per year). Unlike the long-established floodplain fields adjacent to larger creeks and rivers, few, if any, open fields or large garden plots once cultivated by indigenous people could be found.

These early groups subsisted by hunting, fishing, foraging, and with whatever could be grown on hastily cleared garden plots. It typically took three years before enough land could be cleared and planted for pasture or grain crops (e.g., rye, oats, and wheat). As in most of New England and New York, sheep were the first livestock to be raised, followed by pigs, cattle, and horses as the farms became more prosperous. Then and now, the long dormant season (often cold, wet, and snowy) required farmers to grow, harvest and store hay and fodder to feed their livestock during the many months when animals could not be pastured (~mid-October through early-May). The northern Catskills region in the late-1700s and early-1800s was an extension of what Vaughn (1995) called “the New England Frontier.”

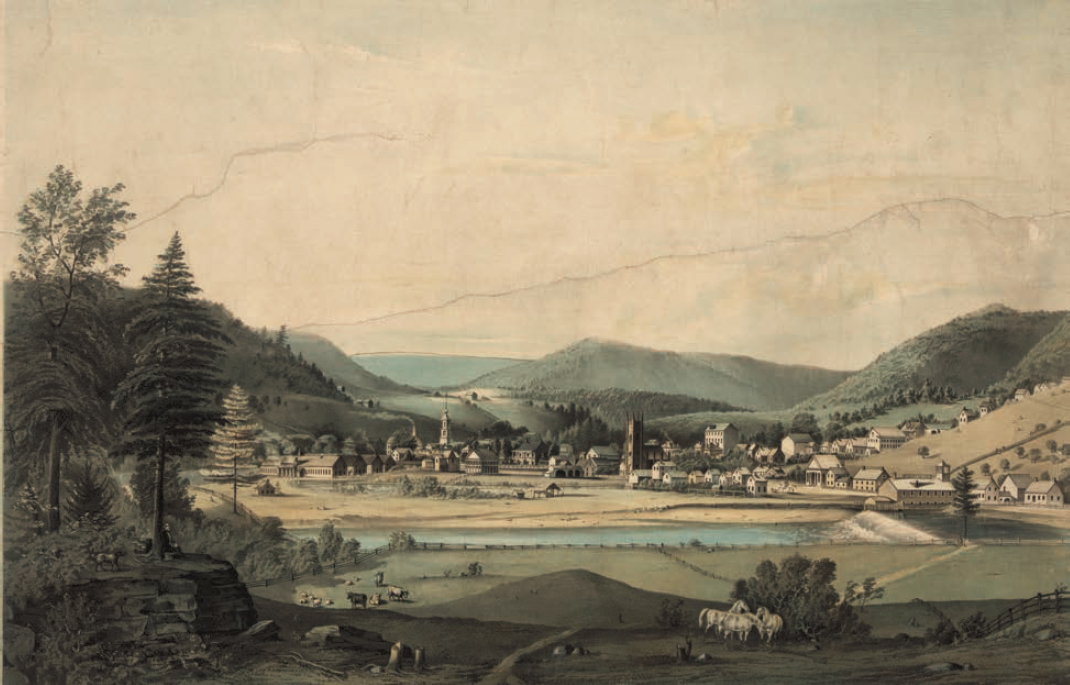

Figure 2-2 exemplifies this time period, although artist Asher Durand (a renowned Hudson River School painter) exercised artistic license with the topography. The dense second-growth forests resulting from the decline of indigenous people has been well documented by landscape ecologists (e.g., Whitney, 1994) and environmental historians (e.g., Cronon, 1983) across the northeastern United States. The forests’ presence has tended to reinforce the erroneous notion that the Catskills and other parts of the U.S. were largely a “pristine wilderness” (Mann, 2006) at the outset of European colonization and settlement.

Some of the earliest farmsteads still exist. When “pioneer” families chose the most productive sites, adapted to and cared for the land, and transmitted the requisite skills and knowledge to their descendants, they are still there—eight, nine, or ten generations later. In contrast, the farm families that arrived later had limited options and attempted to settle on less-productive hillsides. In many cases, they struggled to survive on this marginal land for two or three generations and, in consequence, were prime candidates to join the great Western migration to the Ohio Valley and beyond (especially after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1821). Their abandoned fields and pastures quickly reverted to even-aged forests.

Western Catskills and Delaware River Headwaters

The considerable distance west of the Hudson River and north of the main stem of the Delaware River, coupled with the challenging topography and trackless forests of Delaware County, delayed Euro-American settlement until 1797 (Duerden, 2007). Gideon Frisbee, a Revolutionary War veteran from Connecticut, located his family farm at the confluence of Elk Creek and the West Branch of the Delaware River (now the site of the Delaware County Historical Association2 in Delhi). His direct descendants still work and farm in Delaware County and are active participants in the Watershed Agricultural Council.3

As their counterparts in Greene, Schoharie, and Ulster counties had done a generation earlier, early arrivals in the western Catskills cleared forests and fitted their farming practices to the challenges and opportunities presented by the land, climate, household needs, and markets. In contrast to the eastern Catskills, the broader valley bottoms and floodplains and the rounded hilltops with deeper, more fertile soils presented better opportunities for long-term success. In two of his most vivid and lyrical essays (“My Boyhood” and “Phases of Farm Life”) John Burroughs (1837-1920) memorialized the essential character of daily life, seasonal changes, and noteworthy events in much of the region during the first half of the 19th century (e.g., the four-day round trip by wagon to sell their butter at the steamboat landing on the Hudson River in Catskill, New York).

In the late 1800s, the Ulster & Delaware, Delaware & Northern, and other railroads connected Delaware County (and adjacent central New York counties) to New York City and other major metropolitan areas. This region quickly became and remained one of the most important dairy farming areas in the United States (1880-1970); not until 1950 was central New York surpassed by Wisconsin as the largest dairy producer in the nation. Delaware County farmers also produced other agricultural goods (e.g., livestock, wool, vegetable crops, maple sugar and syrup, hops, and grain crops). This diversification of the rural/regional economy fostered the sustained growth and prosperity of towns and villages well into the 20th century. This historical precedent is especially noteworthy since revitalizing, diversifying, and expanding the farm and forest economy and making

___________________

2 See http://www.dcha-ny.org.

3 See https://www.nycwatershed.org/about-us/success-stories/conservation-easements/the-frisbees/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhbOiuqNHzo.

direct connections to the NYC market are core 21st century objectives of the Watershed Agricultural Council, Watershed Agricultural Program, Watershed Forestry Program, Delaware County Planning Department, Cornell Cooperative Extension, Delaware County Soil and Water Conservation District, chambers of commerce, civic and community organizations, and several state and federal agencies.

Before the advent of the railroads, the geographic isolation of Delaware County and the hardships encountered and overcome during the early settlement period fostered a community-oriented, yet stalwartly independent and self-reliant culture among its residents. These pioneer values and attitudes would become plainly evident during the Anti-Rent War (1839-1845) (Duerden, 2007). This conflict began in Andes, New York, and quickly spread to other communities (Blenheim, Bovina, Middletown, and Roxbury). The “Calico Indians” (so-called because of their unconvincing disguises) rejected the economic and political legacy of the manorial system associated with the Dutch patroonships and English land grants and sought to rid themselves of rapacious landlords. “War” or rebellion are not exaggerated terms for a series of events that led to the shooting death of an undersheriff, 300 militiamen deployed by the governor, 242 arrests, and the construction of temporary jails on Courthouse Square in Delhi. Subsequent trials and convictions led to six life sentences in the Clinton State Prison and scores of two- to ten-year sentences (Duerden, 2007:50-53). Similar attitudes reemerged in the 20th century in the form of rapid and resolute opposition to infringements on property rights, support for individual freedoms and home rule, milk strikes in the 1930s, and resistance to the use of eminent domain and subsequent construction of the NYC reservoirs from the 1930s to the 1960s. More recently, the immediate resistance to NYC DEP’s proposed 1990 Watershed Rules and Regulations and the formation of the Coalition of Watershed Towns and the Watershed Agricultural Council led to the negotiation of the MOA and the Watershed Protection Program.

After more than two centuries, working farms and working forests form the basis of Delaware County’s history, landscape, and culture. It follows that the watershed protection efforts (plans, programs, practices and people) with the best prospects for long-term support and success are based upon a thorough understanding of the past, the salient science, and “politics of the possible” for all concerned: rural residents, rural communities and New York City.

19TH CENTURY INDUSTRIES AND COMMUNITIES

Historians often use 1820 to mark the general transition from an agrarian to an industrialized economy in the eastern United States. In the northern Catskills, the emergence and rapid growth of the tanning industry would transform a late successional forest with a large proportion of mature Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) trees to the greatly altered precursor of its 21st century condition. The lucrative tanning industry and associated road access would also usher in a sequence of other land and resource uses. They included, but were not limited to, logging, sawmills, charcoal production (for iron furnaces near Millerton, New York), cooperage mills (butter firkins, tubs, and barrels, etc.), bluestone quarrying, sheep and cattle production, dairy farming, and furniture manufacturing. For example, the natural regrowth of deciduous trees after the mature hemlock was cut became a resource for barrel hoops and chair parts as soon as they reached the sapling stage (~1 inch in diameter). Alternatively, if the hemlock “slashings” were burned (either accidentally or deliberately), the cleared land could be used for rough sheep pasture or, with much more effort, be converted to the cropland, pastures and hayfields needed for dairy farming. In other cases, the hemlock logs left by the bark peelers were sometimes dragged by oxen or draft horses or floated downstream to small sawmills where they were cut into beams and lumber.

The diversity, scale, and widespread spatial distribution of 19th century mills and factories (see Table 2-1) may seem implausible, even incomprehensible, to 21st century visitors to a verdant landscape now dominated by mature forests and dotted with farms, rural homes, and small communities. While the passage of time has obscured many of the signs and symptoms of 19th century land and resource use, many interrelated ecological, geographical (e.g., roads and communities in stream valleys), economic, cultural, and political legacies persist. They, in turn, have substantially influenced: (1) the development of the NYC water supply system, (2) the architecture and intent of the MOA, and (3) the evolution of the Watershed Protection Program.

TABLE 2-1 Tally of Major 19th Century Industries by Type and Watershed

| Watershed | Tanneries | Sawmills | Furniture Factories | Cooperage Mills | Charcoal Kilns | Bluestone Quarries | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Branch of Delaware River | 13 | 75 | 10 | 3 | - | 18 | 119 |

| Neversink River | 3 | 8 | 7 | 1 | - | - | 19 |

| Schoharie Creek | 25 | 74 | 28 | 5 | - | 14 | 146 |

| Esopus Creek | 16 | 73 | 38 | 27 | 19 | 45 | 218 |

| Rondout Creek | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 | - | - | 15 |

| Totals | 58 | 238 | 85 | 40 | 19 | 77 | 517 |

SOURCE: Adapted from Kudish (2000:153).

Tanneries

Tanning at an industrial scale in the 1800s required three things: (1) a large supply of hides as the raw material for leather; (2) abundant quantities of water for the tanning process, to provide waterpower, and to carry away copious wastes (hide scrapings, hair, spent tanning liquor, and any other refuse); and (3) a source of tannic acid (Canham, 2011; Millen, 1995). The high biochemical oxygen demand and low pH of the tannery effluent dumped into mountain streams usually decimated native brook trout populations and the aquatic ecosystem. At the peak of tannery production in the mid-1800s, many streams were thought to be “polluted beyond recovery” (Evers, 1982). Pollutants from other industries (e.g., sawdust and scraps from sawmills and furniture factories), unlimited access to streams by livestock, manure from barnyards and streamside pastures, and effluent from pit privies only made matters worse.

In the Catskills, tannins were derived from dry hemlock bark ground into a fine powder then dissolved in water to make tanning liquor for “the pits.” Seemingly inexhaustible quantities of large, mature hemlock trees, large perennial streams, and long-distance transportation routes via the Hudson River—for raw hides coming in, and finished leather going out—made the region an efficient, if not ideal, location. Entrepreneurs and master tanners such William Edwards (1817 in Tannersville and Hunter), Zadock Pratt (1825 in Prattsville), Henry D. H. Snyder (1849 near Phoenicia), and many others would dramatically alter the forests, streams, settlement patterns, and economy of the Catskills. Kudish (2000) documented 64 tanneries in the region.

Ultimately, the Catskills region became the largest producer of sole leather in the United States between ~1820 and 1870. During this 50-year period, millions of mature hemlock trees were cut, peeled, and typically left to rot. Entire mountainsides were strewn with bleached white trunks and dry, highly flammable tops. Inevitably, many of these cutover sites burned. Although it is not possible to accurately quantify the short-term and long-term effects of 19th century exploitive logging and subsequent wildfires, it is reasonable to suppose that snowmelt rates, overland flow, soil erosion, sediment transport, nutrient mobilization, stormflow peak discharge, and annual water yield simultaneously increased. These elevated levels would have persisted until forest regeneration was well established (NRC, 2008).

Some tanners, Zadock Pratt in particular, cut hemlock stands with the specific intent of selling the partially cleared land to farmers. If the site was converted to pasture or cropland, that would help to stabilize the site. However, the hydrological parameters listed above would remain well above baseline forest conditions and reflect the scale and intensity of agricultural use and the effectiveness of land stewardship (de la Crétaz and Barten, 2007). The larger tanneries often formed the nucleus of company towns and trading centers (Evers, 1982; Millen, 1995) (Figure 2-3), thereby concentrating more people and environmental impact along the major streams.

Wood-Using Industries: Logging, Sawmills, Furniture Factories, Cooperage Mills, and Charcoal Kilns

Relatively small, water-powered sawmills were built and operated on virtually every large stream or small creek in the Catskills. A stair-step sequence of sawmills lined the banks of some creeks. Hemlock logs were free for the taking and so abundant that sleepers and thick boards were produced to build “plank roads” (Duerden, 2007; Evers, 1982). After paying a turnpike toll, heavy wagons could travel on these private roads in the Esopus and Upper Delaware valleys and largely avoid mud, pools, potholes, and dust. Other tree species such as red and white oak were sawn into beams, lumber, and railroad ties. White pine and red spruce were used to produce clapboard siding, flooring, and most of the other building materials needed for houses, barns, and commercial buildings.

Some of the larger furniture factories had their own sawmills to make hardwood stock in custom sizes needed for their ultimate products: chairs, benches, tables, desks, and cabinets. Furniture factories were not

small artisan workshops or cottage industries. For example, the Schwartzwaelder Company, located on the Stony Clove in Chichester, produced high-quality furniture and shipped it by the boxcar load to markets as distant as Mexico City (Bennett, 1999).

Similarly, some cooperage mills produced the materials needed to manufacture barrels, tubs, buckets, and other items. Firkins (heavy wooden tubs that could hold about 50 pounds of salted butter) were used by Catskill Mountain dairy farmers to store and transport their most important cash crop, as well as for maple sugar or cheese. Large quantities of hardwood saplings were cut to supply barrel “hoop wood” to coopers in the Catskills, Hudson River valley, and New York. Furniture factories and cooperage mills were also located directly on streams or creeks to provide waterpower for their belt-and-pulley systems. Even when many factories and mills later converted to steam power, they were not moved. More commonly, they expanded in both scale and environmental impact (i.e., encroachment on the stream channel).

The term charcoal kiln evokes a brick or stone structure and a controlled industrial process. In the Catskills (and the Berkshires of Massachusetts and Litchfield Hills of Connecticut) “kilns” were simple open hearths—flat, circular, stone-free clearings on which 20 to 30 cords of firewood were carefully stacked and then covered with wet leaves and earth. The wood came from 2- to 3-acre (~1 hectare) clear-cuts of all useable trees in the immediate vicinity. In northwestern Connecticut, where charcoal production was more prevalent, trees were cut at 20- to 30-year intervals——a practice local residents accurately referred to as “stripping.” Once ignited, the smoldering fire within the mound had to be carefully tended—night and day—for two to three weeks to produce several wagonloads of charcoal (pure carbon). Before it was replaced by anthracite coal or coke as the fuel for blacksmith’s forges and ironmonger’s blast furnaces, charcoal was an essential raw material. Charcoal from the Catskills (largely in the Esopus Creek watershed) was produced in large quantities to supply the blast furnaces in Millerton, New York.

In and around the two branches of the upper Delaware River, loggers floated white pine, hemlock, and red spruce logs down to the main stem, assembled them into large log rafts, and floated downstream as far as Trenton, New Jersey, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to supply major sawmills (Figure 2-4). The limitless demand

for building materials in these rapidly growing cities made this a profitable enterprise. Raft crews made their way back to Delaware County as best they could, on foot, by stagecoach, and later by railroad (until the railroad system put them out of business). The last log drive took place in 1919 (Studer, 1998).

Bluestone Quarries

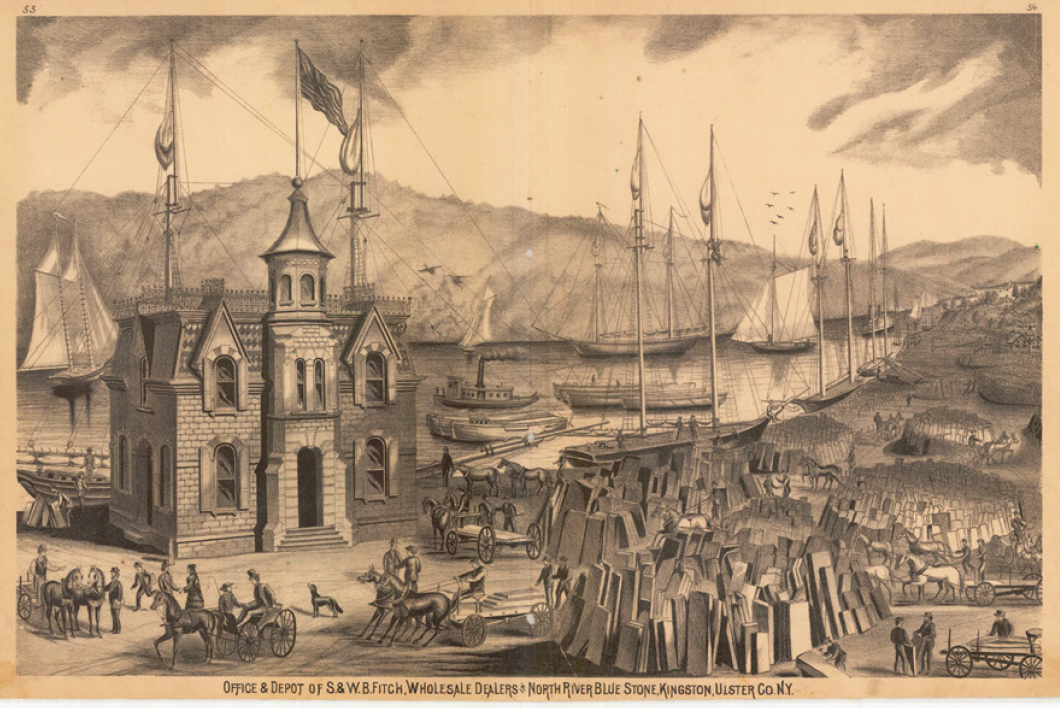

Bluestone is a durable, fine-grained, and versatile blue-gray siltstone that was produced in very large quantities by scores of Catskill Mountain quarries from 1830 until about 1900. A sedimentary rock with relatively uniform horizontal bedding planes, it was extracted in large “lifts” [slabs] with iron wedges, sledge hammers and derricks, loaded on heavy wagons, and transported to “stone docks” along the Hudson River or the Rondout Creek in Kingston (Figure 2-5). The most common products of the stonecutters were large, neatly finished sidewalk slabs. Albany was the first city to use it widely, to be followed (in the 1850s) by New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston. By the early 1900s, Catskill Mountain bluestone was being used for sidewalks in San Francisco, Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Havana (Evers, 1982). In addition to sidewalks, bluestone was well suited for curbing, walls, hitching posts, mounting blocks, carriage steps, front stoops and door-frames, sills and lintels, troughs for livestock, workbenches for blacksmiths and wheelwrights, and tombstones. (Much bluestone was used in the W. H. Vanderbilt mansion on Fifth Avenue and the Tiffany house on Madison Avenue in New York City).

The most common 19th century complaints about bluestone quarrying centered on the ugly scars caused to mountainsides, the dust and noise caused by blasting with black powder, and the “perilous wagon roads” (implying steep, rutted, and unstable) needed to reach the larger turnpikes and plank roads (Evers, 1982; Evers

et al., 2008). It is likely that wagon roads, and wagons with 20-ton loads and two- or four-draft horse teams caused most of the adverse environmental impacts. As noted earlier, most roads follow streams in their narrow floodplains.

Pastures, Hayfields, and Cropland

In addition to the agricultural land needed for sheep production and dairy farming, all of the industries and activities described above required large numbers of draft horses for day-to-day operations. Some teams were supplied by farmers seeking short-term seasonal work and a supplemental cash income. Many draft horses were owned by the teamsters who hauled raw hides in from Hudson River landings to the tanneries, and leather, lumber, bluestone, cooperage, furniture, wool cloth, and many other Catskill Mountain products out to Hudson River ports. Before the railroads largely replaced them in the late 1800s, the total number of draft horses had to match the tonnage and volume of goods and the lengthy travel times. One account may help the reader appreciate the scale of this form of transportation. The Snyder Tannery in Woodland Valley routinely sent a convoy of 50 wagons (100 horses) down the Plank Road (now NYS Route 28) to haul leather to Kingston on the Rondout Creek, then return with salted raw hides. Consider the number of enterprises listed in Table 2-1 as starting point for an estimate of the total number of horses that were needed.

A draft horse in harness consumes about 30 pounds of grass or hay, 10 to 15 pounds of grain (oats or field corn), and about 10 gallons of water per day. Larger horses doing the most demanding cold-weather work (e.g., skidding logs or hauling freight wagons) can require twice this much food and water. In addition, each horse needs at least two acres (1 ha) of summer pasture. Hence, large areas of pasture, hayfield, and cropland (thousands of acres) were needed to fuel this mode of transport. Whitney (1994) found that most of the extensive farmland in 19th century Maine was devoted to growing feed for horses working through the long winters in the logging camps. In the Catskills, many of these fields would have been proximate to streams and creeks on the more fertile soils and accessible sites (i.e., the yellow areas in Figure 2-7). It follows that increased water yield (after forests were cleared), soil compaction, sediment transport, and nutrient and pathogen loading from manure would be directly proportional to the cleared area and number of animals. There would have been site-specific variation related to the number of horses (and other livestock), soils and topography, and intensity of use, but the adverse effects on streamflow and water quality must have been substantial.

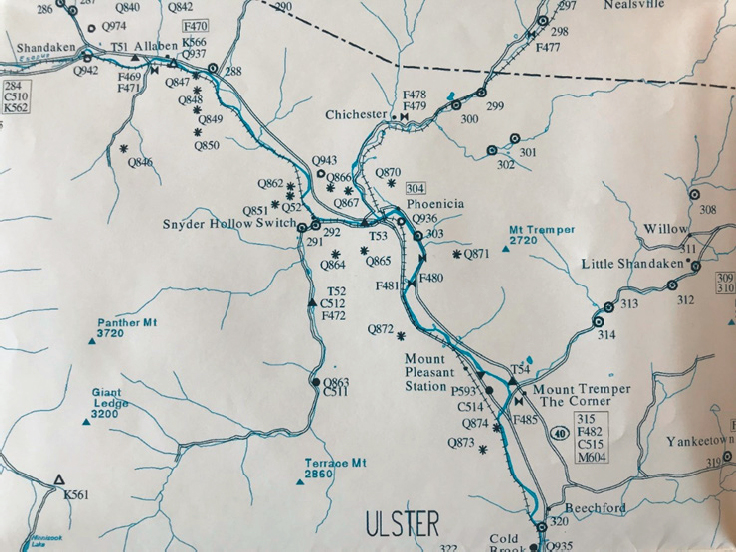

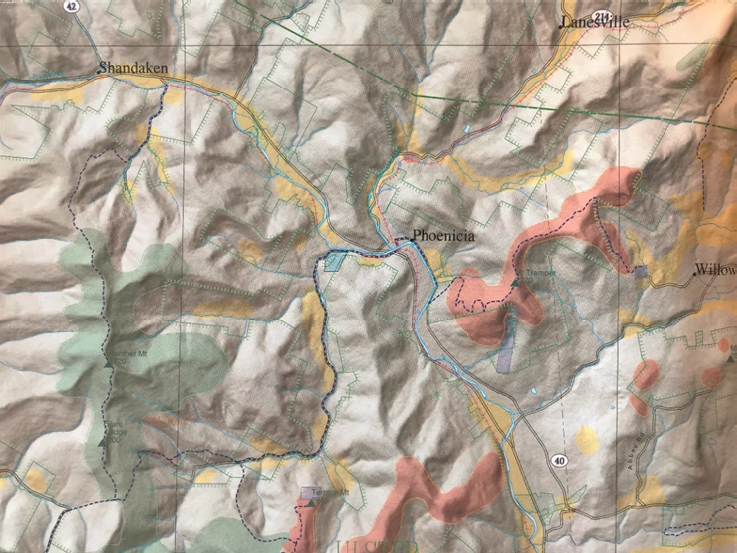

Cumulative Effects

Derived from decades of field work and meticulous mapping, Kudish (2000) shows the extent and lasting influence of earlier land and resource uses in the Catskills. In particular, it highlights how the terrain, the need for waterpower, and transportation infrastructure linking commercial enterprises to the Hudson River and distant markets set the stage for 20th and 21st century conditions. The companion maps presented in Figures 2-6 and 2-7 (small portions of Kudish’s regional maps) show the cumulative effects of human actions. The key point of the preceding sections, the maps below, and contemporary conditions in the Catskills (i.e., high percentage of forest cover and very high ambient water quality) is the remarkable resilience and recovery of the forests, streams, and aquatic ecosystems after a long period of widespread, intensive, and unregulated land and resource use. This is not to suggest that due diligence with watershed management and source water protection is not essential, but rather to note that a “pristine wilderness” with no people and no human activities is not a necessary precondition for the production of clean water.

TWO WORLDS MEET

In his monumental 700+-page history of the Catskills, Evers (1982) describes the parallel, then converging paths of two worlds: (1) the workaday world of tanneries, sawmills, quarries, farms and rural communities and

#), roads, railroads, and communities in the vicinity of Phoenicia, New York, Woodland Creek, Stony Clove Creek, and the Esopus Creek. Figure in color at https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25851/. SOURCE: Kudish (2000). Courtesy of Michael Kudish and Purple Mountain Press.

#), roads, railroads, and communities in the vicinity of Phoenicia, New York, Woodland Creek, Stony Clove Creek, and the Esopus Creek. Figure in color at https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25851/. SOURCE: Kudish (2000). Courtesy of Michael Kudish and Purple Mountain Press.

(2) the aesthetic world of art, literature, and elite tourism and leisure. In the 1830s and 1840s, the Catskills had enough room for these two worlds to coexist or at least to largely ignore one another in the ~1-million-acre region. However, as the scope, scale and influence of each world grew, the inevitable conflict over incompatible uses and fundamentally different values and attitudes emerged. The end of one world (1750s-1890s, more than a century of unfettered resource extraction) and the overlap with and transition to a new world (1830s to present, tourism and renewable resource management) would take place in the first few decades of the 20th century.

This new perspective on the values, goods and services associated with the Catskills was fostered, at least in part, by gifted writers and artists who fired the imagination of affluent city dwellers. Longing to experience the scenes depicted in books and paintings, they were enthusiastic visitors to the region. This perspective was also at the heart of the preservationist goals of John Muir and the Conservation Movement led by Gifford Pinchot, Theodore Roosevelt and others in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Successfully overcoming the challenge of time and distance between urban areas (principally New York City) and the Catskills was another key agent of change. In less than two generations, railroads and steamboats transformed the arduous circa 1830 journey to a rugged, isolated region into a stately and genteel trip to an exclusive destination. Ultimately, the conflict between incompatible uses and expectations (e.g., tanneries versus trout fishing, sawmills versus primeval forests, bluestone quarries versus unblemished mountain views) and other political and cultural changes would lead to the establishment of the Catskill Forest Preserve. The subsequent recovery of forests and aquatic ecosystems, streamflow regimes, and water quality happened to occur just before they were urgently needed to expand the New York City water supply system.

Art, Literature, and Travel

The Catskills usually became known to well-educated, affluent residents of New York and other major cities (e.g., Baltimore, Charleston, and Philadelphia) in serialized articles, books, essays, and art exhibits. Washington Irving’s (1783-1859) talent, imagination, authentic American pedigree, and intuitive sense of his audience made him one of the most influential and widely acclaimed American authors of his day. He adapted Rip Van Winkle from the outline of a German folktale and it became an overnight success upon publication in 1819. It quite literally introduced the Catskills to the outside world at a time when the influence of the Dutch Colonial Era was still clearly evident.

Irving’s contemporary, James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) wrote a widely acclaimed series of five books——“The Leatherstocking Tales”——between 1826 and 1841. Action-adventure best sellers of 19th century, they included vivid descriptions of a vast and majestic wilderness (with frequent references to the Catskills, Adirondacks, and Finger Lakes) and accurate historical references to the Colonial Era, French and Indian War, and American Revolution.

John Burroughs (1837-1920) was a noted naturalist and popular writer who was born on a farm in Roxbury, Delaware County on land cleared by his grandparents. A close friend of Walt Whitman and later John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and other luminaries, his work was serialized in literary magazines, then collected and republished in 21 books (between 1871 and 1922). By coincidence, Burroughs captured the essential character and condition of the Catskills when New York City expanded its water supply system into Esopus and Schoharie watersheds in the early 1900s and the Delaware, Neversink and Rondout watersheds in the 1930s-1960s. Many of the farm families and rural communities encountered by the NYC Bureau of Water Supply had the same deep roots and traditional lifeways linked to the seasons described by Burroughs in the 19th century.

Ironically, at the same time that the tanners, “cut and run” loggers, quarrymen, and market hunters were converting the natural resources of the Catskills into cash, the beautiful and rugged vistas, vibrant fall foliage, and captivating history of the region attracted painter Thomas Cole and led to the establishment of the Hudson River School. This genre of landscape painting was rapidly advanced by his students and associates: Asher Durand, Frederic Church, Jasper Cropsey, Sanford Gifford, George Inness, John Kensett, and, later, Albert Bierstadt. In affluent homes and mansions in every eastern city, especially New York, their paintings presented

the Catskills as a majestic, pristine wilderness. If people and human activities were included, they were tiny figures shown for scale or as a nostalgic tribute. In combination with the writings of Irving, Cooper, Burroughs and others, these paintings have created an enduring image of the Catskills that persists in the minds of many to this day (Figure 2-8).

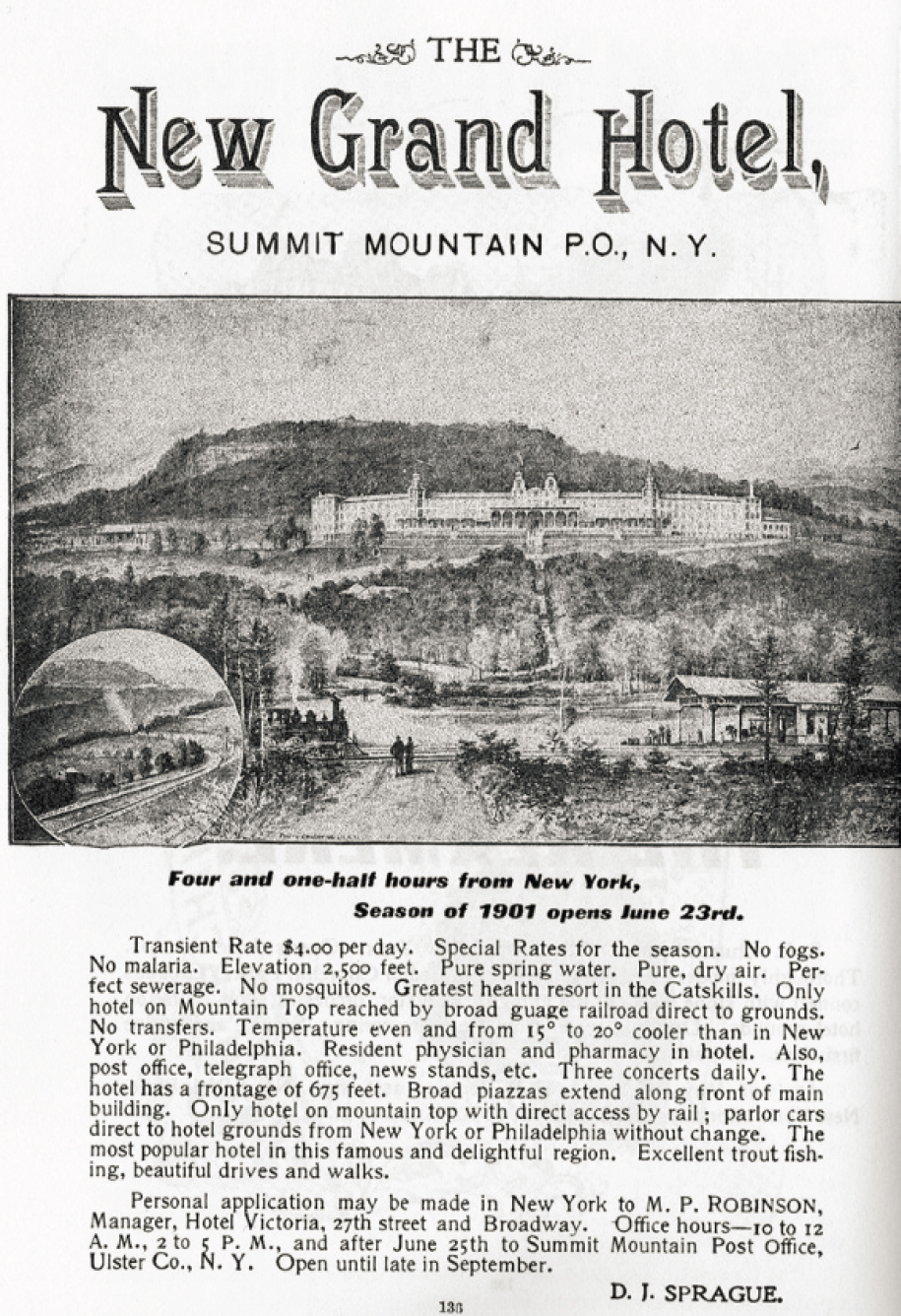

A third defining feature of the region was (and still is) tourism. In an age of global travel, when regular vacations and holidays are enjoyed by many Americans, it is difficult to imagine a time when travel and leisure were exclusively limited to the ultra-wealthy. If you had the means and opportunity to escape the oppressive heat and unsanitary conditions in cities4 by partaking of the blissful scenes in paintings and literature, you acted on that impulse. The pent-up demand for an escape to a clean, healthy, restorative environment was first met by the Catskill Mountain House in 1824. It set the pattern for many others that followed (e.g., Laurel House, Kaaterskill Hotel, Overlook Mountain House). By 1901, The Ulster & Delaware Railroad guidebook listed 50 inns, hotels, and boarding houses, ranging in size from the massive Kaaterskill Hotel (1,200 rooms) to small family enterprises with accommodations for 10 or 20 guests. A sample advertisement for the New Grand Hotel (Figure 2-9) is typical of many others and illustrative of what guests and proprietors valued at the time. A key selling point was the 4.5-hour train trip between New York and the hotel (the same amount of time required to make the drive today.)

___________________

4 Imagine New York in the early -1800s with 100,000-200,000 horses, 20,000 hogs, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and no air-conditioning.

Steamboats and Railroads

Steam power revolutionized transportation in the United States and many other parts of the world. In 1807, Robert Fulton demonstrated the viability and potential for river transportation on the Hudson with the North River Steamboat, also known as the Clermont. His design built upon earlier successful prototypes in Scotland, France, England, and Philadelphia in the late 1780s. The first steam locomotive in New York State (the DeWitt Clinton) began operation in 1831 on the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad, operating in concert with the Erie Canal. Both forms of transportation were so promising that investment and American ingenuity quickly accelerated their development and use. The Hudson Day Line (and night boats) were the exclusive cruise ships of their day (1863-1948), whisking passengers up the river at sustained speeds of 25 miles per hour. Similarly, steam locomotives routinely traveled at comparable speeds (including station stops) but were capable of 45-60 mph when traveling as express trains. Travel between New York City and the Catskills became routine enough for the wives and children of affluent families to spend the entire summer while husbands/fathers arrived from New York City on Friday evening and returned on Sunday afternoon.

Two regional railroads linked the Catskills to the rapidly expanding national network. The Catskill Mountain Railway (1880-1918, and smaller subsidiaries) originated at the steamboat landing and New York Central West Shore Line station in Catskill, New York. It traveled along the base of the escarpment, then turned west, ending in Tannersville, New York. The Ulster & Delaware Railroad (1866-1932) originated in Kingston, New York. It followed the Esopus Creek valley, then passed over the watershed divide into Delaware County, connecting to Oneonta, New York, in 1900. Both railroads carried tourists to and from the Catskill Mountain houses. The Ulster & Delaware, in particular, provided a cost-effective connection for Catskill Mountain commodities (dairy products and bluestone) to reach distant markets. The new stations in small towns fostered the growth of inns and boarding houses. In one generation, the railroads ended the relative isolation of the region and ushered in a period of sustained prosperity based on a diverse economy of tourism, agriculture, manufacturing, and natural resources. This prosperity also generated popular support for restoring and protecting the scenic and ecological values of the Catskills.

Catskill Forest Preserve

The Catskill Forest Preserve (CFP) permanently protects a major portion of the headwaters of the New York City water supply system. Its establishment in 1885 was not a response to the conflicts and challenges described above. Rather, the CFP has its origins in State Assemblyman Cornelius Hardenbergh, who was also a former member of the Ulster County Board of Supervisors (Van Valkenburgh and Olney 2004, 2008). Hardenbergh seized the opportunity to establish the Catskill Forest Preserve (34,000 acres) as an amendment to a bill creating the 681,000-acre Adirondack Forest Preserve5 and, in so doing, circumvented the taxes customarily paid by counties to the state. Protection of about 10 percent of the Adirondacks was being sought to avoid the wholesale repetition of the cut and run logging, tanbark peeling, and associated impacts that had already occurred in the Catskills. It was thought to be too late to 13protect the Catskills, where 94 percent of the landscape had been altered by human activity.

When the Catskill and Adirondack Forest Preserves were finally established, proponents of this new paradigm of forest protection cited the recommendations of distinguished experts such as Prof. Charles Sprague Sargent and other members of the Forest Commission, as well as Dr. Franklin Hough. The forest protection initiative and calls for lasting change also reflected the growing sense of urgency inspired by the more widely read work of Marsh, Hough, Muir, and Burroughs, especially among the urban elite. Their firsthand observations and experiences while vacationing in the Catskills or Adirondacks increased their fervor for action. Nevertheless, the financial and economic implications of this major philosophical and policy change continued to fuel a pitched political battle. The permanent withdrawal of undeeded areas from the general list of available land in the Adirondacks and the exclusion of railroads, logging, mining, and quarrying in both forest preserves

___________________

5 Now 2,928,000 acres (48 percent) of the 6,100,000-acre Adirondack Park (https://apa.ny.gov/about_park/index.html).

were the key points of contention. The pivotal question of forest protection was put to a vote in the 1894 referendum to amend the New York State Constitution, with the following result: 410,697 For, 327,402 Against.

The lands of the state, now owned or hereafter acquired, constituting the forest preserve as now fixed by law, shall be forever kept as wild forest lands. They shall not be leased, sold or exchanged, or be taken by any corporation, public or private, nor shall the timber thereon be sold, removed or destroyed.

As public support for forest protection continued to gain momentum in early 20th century, so did political responses in the form of substantial appropriations and bond acts. As a result, the area of the Catskill Forest Preserve tripled in size by 1916 (105,000 acres). A new bond provided the financial and staff resources that doubled the size of the CFP to 215,500 acres by 1944. Some land came into the public domain as a result of delinquent taxes during the economic upheaval caused by the Great Depression. In addition to tax-delinquent properties and willing seller-willing buyer transactions, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation was granted the power of eminent domain. It was, however, rarely used in the Catskills or the Adirondacks.

Popular support for “environmental protection” continued to grow in the post-World War II era with growing interests in camping and other forms of outdoor recreation and the influence of a new generation of writers (e.g., Leopold, Carson, and Olson). More bond acts were passed in 1960, 1962, and 1972 with impressive pluralities, such that the CFP was enlarged to its current area of 288,000 acres.

Three lessons flow from the ~150-year history of the Catskill Forest Preserve. First, forest conservation and watershed protection require sustained, cumulative efforts on multiple fronts. Second, values and attitudes change over time, especially when positive reinforcement accrues from the success of the program or project. Third, there comes a time when core goals have been achieved, the success of the project or program can be affirmed, and a new custodial management phase can begin.

20TH CENTURY CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE

Except for well-established dairy farms and the smaller resorts, the early 20th century was a quiet time across much of the Catskills. The tanneries, quarries, cooperage mills, and most of the sawmills were gone, though a few furniture factories remained profitable until the Great Depression and competition swept them away. Summer camps for children were established and grew in popularity, and some families from urban areas maintained second homes. Hunting and fishing, especially for trout (both wild and stocked fish), grew in popularity as roads and highways continued to improve. In general, though, the region was regarded as an old-fashioned place. Limited employment opportunities and incomes for year-round residents contrasted sharply with the affluence of summer visitors and second homeowners. The establishment of ski areas (e.g., Belleayre, Simpson’s, Highmount, and Hunter Mountain) provided seasonal employment, more patrons for small hotels and restaurants, and weekend traffic. The cultural contrasts between the Catskills and New York City grew more pronounced.

New York City’s Catskill water supply system had become a long-established entity. Except for the strict prohibitions on access and hunting, it was more or less accepted or ignored by local people in the eastern Catskills. In contrast, the Delaware water supply system was still new, and the recent, large-scale use of eminent domain was a source of bitter resentment. Delaware County and parts of Schoharie and Greene counties had large numbers of dairy farms and reliable, long-standing links to regional markets. The continuing improvement of roads ushered in two other changes. Commuting substantial distances for employment became more common for year-round residents as did the consolidation of small rural school districts into comparatively large central districts with long-distance bus transportation.

21ST CENTURY CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE

The first two decades of the 21st century have ushered in more changes in the Catskills region and the New York metropolitan area. Changes in many professional fields have led to a substantial increase in second-home ownership in the region (Clemence, 2019), such that it is now possible to relocate or colocate New York City-based livelihoods, at least to the southern Catskills (outside of the NYC water supply system). As high-speed Internet access moves northward, it is likely to augment the growing number of people who live in the watershed and drink well water for part of the week, then live in New York City and drink water delivered by the NYC DEP for the balance of the week (Delavan, 2020; Satow, 2019). In addition, short-term rental properties, destination wedding sites, and boutique bed & breakfast establishments have expanded rapidly (Applebone, 2019). Facsimiles of the 19th century farm boarding houses and small mountain houses have reappeared in the form of wellness retreats, farm-to-table dining, artisanal food production and craft brewing, active outdoor recreation, and country fairs and festivals (Vu, 2015). The number and diversity of artists and craftspeople also appear to be growing. Snowmaking, slope-side condominium development, four-season events and amenities, and more highway improvements have enhanced the viability of ski areas and associated town centers. In sum, the same inspiring scenery, extensive forests, clean air and water, peace and quiet, recreational opportunities, and modest real estate costs (relative to New York City and its suburbs) that attracted city dwellers in the 19th century are still extant in the 21st century (Lasky, 2020). At the same time, the balancing act between tourism and traditional uses of the land and natural resources, the changing proportion of part-time and full-time residents, and many other challenges for rural communities persist.

Two trends warrant particular attention in relation to community vitality. First, Delaware County mirrors national demographic trends for rural communities and agricultural landscapes. Specifically, the population is decreasing and aging. Farms are going out of business or struggling through intergenerational transfers. Weak and volatile commodity markets for dairy products, in particular, have stretched traditional approaches to farming to the breaking point. Declining enrollments in schools and vital recruitment for volunteer fire departments and rescue squads, to name a few, are also causes of concern. Many dedicated people, organizations, and agencies are working diligently and creatively to address these economic and demographic challenges and to develop new opportunities. The Delaware County Planning and Economic Development Departments,6 Delaware County Chamber of Commerce,7 Watershed Agricultural Council (WAC), and Catskill Watershed Corporation (CWC) are all working to balance and enhance watershed protection, economic vitality, and social well-being over the long term. NYC DEP provides major financial support for many of these initiatives (e.g., WAC’s Pure Catskills program,8 CWC’s Regional Economic Development and Micro Loan programs9).

The second noteworthy change is the general increase in timber harvesting as valuable tree species (such as white ash, sugar maple, yellow birch, and northern red oak) reach sawtimber sizes (>10-12 inches in diameter). These second-growth and third-growth forests originated with the land and resource uses in the 19th and early 20th century. The global market for forest products extends into the Catskills through a small cohort of local mills and furniture manufacturing firms, and a larger cohort of high-volume sawmills in central and western New York. The hardwood lumber produced by these large mills is shipped worldwide (principally to Asia and Europe) for use in furniture manufacturing and building construction. Avoiding the unsustainable practices of the earlier eras is critical to managing forests in a way that maintains or enhances water quality and forest health.

___________________

6http://www.co.delaware.ny.us/departments/pln/pln.htm/ and http://dcecodev.com/

7http://delawarecounty.org/ and https://greatwesterncatskills.com/

THE HUMAN DIMENSIONS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NYC WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM

In the early-1900s, most communities and farms in the Catskills had been stable and prosperous for several generations. The rapid regrowth of the forests once felled for tanbark and sawtimber, rebound of water quality and aquatic ecosystems, celebration of the Catskills in art and literature, establishment of the CFP, and reliable railroad connections to New York City all contributed to this contented existence (DeLisser, 1896; Du Mond, 1988; Steuding, 1985). For decades, New York City residents came to the Catskills for the summer, spending substantial amounts of money, then returned home. Trains made daily “milk runs” to the seemingly limitless market for farm produce in the City, but in other ways, contact with the outside world was limited. It came, therefore, as a sudden shock when the vanguard of the NYC Bureau of Water Supply (BWS) abruptly arrived to begin work on the expansive Catskill system. The broadest valley in the Esopus Creek watershed and the nature of the interaction between rural communities and New York City would be unalterably changed in less than a decade.

Table 2-2 compares the population of the watershed residents displaced by construction of the water supply system to the concurrent population of New York City. The human experience and community transformation subsumed in the dates, place names, and population statistics in Table 2-2 are highlighted by the following excerpt, based on the detailed records of the NYC BWS pertaining to the Pepacton Reservoir (Galusha, 2016:210):

TABLE 2-2 NYC Reservoirs, Construction Dates, Communities and People Displaced, and Contemporaneous U.S. Census Population Data for New York City

| Reservoir | Time Period | Communities Displaced | People Displaced | NYC Population (U.S. Census) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashokan | 1907-1915 | Ashton, Bishop’s Falls, Boiceville, Brodhead, Brown’s Station, Glenford, Olive Bridge, Olive City, Shokan, Stone Church, West Hurley, West Shokan | 2,000 | 4,766,883 (1910) |

| Schoharie | 1919-1927 | Gilboa | 350 | 5,620,048 (1920) |

| Rondout | 1937-1954 | Eureka, Montela, Lackawack | 1,500 | 7,457,995 (1940) |

| Neversink | 1941-1953 | Neversink, Bittersweet | ||

| Pepacton | 1947-1954 | Arena, Pepacton, Shavertown, Union Grove | 974 | 7,891,957 (1950) |

| Cannonsville | 1955-1967 | Beerston, Cannonsville, Rock Rift, Rock Royal, Granton | 941 | 7,894,862 (1970) |

SOURCES: Galusha (2016); Steuding (1985); https://cwconline.org/history-of-the-nyc-water-supply/; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_New_York_City#Historical_population_data.

After the first two real estate sections closest to the dam were taken in 1947, six more sections were claimed between September 1950 and April 1954. A total of 13,384 acres—21 square miles—were claimed for the reservoir. Forced to move were 974 people, including 284 children and 46 wards of the state and county. The BWS counted 260 residences, 113 farms, 8 churches, 8 garages, 3 taverns, 3 hotels, 8 sawmills, 2 barber shops, 2 water companies, 5 schools, 4 post offices, a Grange hall, a feed store, a fire house and chiropractor’s office. Enumerators even counted livestock—2,336 cows, 6,135 chickens, 103 horses, 99 pigs, and 24 sheep and goats.

Also removed were 2,371 graves in 10 cemeteries. The city paid to have bodies disinterred and moved to a cemetery chosen by relatives. Some 600 unclaimed bodies were reinterred on the Ken Sprague farm near Shavertown, a farm the city acquired for that purpose. Sprague, who milked 34 cows on the 168-acre farm, returned from the doctor one afternoon to find a condemnation notice nailed to a shed door.

One of the 113 farms is memorialized in a photograph by Bob Wyer, a gifted artist from Delhi, New York (Figure 2-10). In a figurative sense, this image also represents the living memories and lingering concerns of many individuals, families, and communities in Delaware County and other parts of the Catskills. The Jacobson’s dignified and stoic expression can be interpreted in many ways. It poignantly evokes an insightful statement by Diane Galusha (2016:231)——based upon years of research and scholarship, community engagement, and professional work with the Catskill Watershed Corporation.

If there has been one common denominator in the city’s multitudinous water projects, it has been the conflict between individual property rights and the needs of the masses. Wholesale condemnation of private properties to build public-benefit projects brought grief to many, fortune to some, and fresh water to millions of consumers largely unaware of the sacrifices made far away on their behalf.

NEGOTIATING THE MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT

In 1990, residents, farmers, business owners, and local political leaders were shocked to read a public notice in newspapers across the Catskills region enumerating page after page of new watershed rules and regulations. NYC DEP’s administrative response to the U.S. Environmental protection Agency’s (EPA’s) new Surface Water Treatment Rule (1989) was to establish a “Filtration Avoidance Program” and dramatically expand the 1953 Watershed Rules and Regulations. This was a concerted effort to avoid, or at least forestall, the construction of a water treatment plant and the associated operation and maintenance costs. Chapter 1 describes the principal components of the MOA, the establishment of the NYC DEP Watershed Protection Program, and a host of partnership agreements and evolving forms of interaction between New York City and watershed communities.

When all was said and done, the MOA was signed in 1997 after years of difficult and often contentious negotiations. In many respects, the MOA functionally redefined the phrase “justified by public necessity” after NYC DEP renounced the use of eminent domain. “Public necessity” now encompasses what New York City and watershed communities strive to do in partnership——protect water quality and foster community vitality—as they implement the MOA. This is an inherently complex task influenced by a long history, cultural differences, divergent priorities, and resource constraints. During site visits to Delaware County, and at its meetings, the Committee heard many versions of the following statement by Tina Molé, chairperson of the Delaware County Board of Supervisors, made at a December 2018 meeting in Delhi, New York:

We continued dedicating ourselves and our staff to upholding our end of a bargain struck two decades ago: the protection of water quality. This water quality is NOT, however, a service that we provide merely for the benefit of the millions of people we’ll likely never meet. It’s much more dear to us. It’s part of our home, part of a landscape that we cherish and respect.

The MOA, the Watershed Protection Program, and a series of filtration avoidance determinations issued by EPA and the New York State Department of Health have enabled New York City to meet state and federal regulatory requirements as well as the expectations of water consumers. Justified by public necessity and informed by a much greater awareness of needs, sacrifices, common interests, and interdependent relationships, the Watershed Protection Program has evolved into a proactive and resilient way to manage and sustain the NYC water supply system.

SUMMARY

The Catskill Mountain region is a long-settled landscape with a forest-farm-tourism economy, adaptable, self-reliant people with deep roots, strong home-rule traditions, and historical precedents for cooperation and resistance. The region has been linked to New York City in many ways for 150 years before the expansion of the water supply system. When the Catskill and Delaware systems were built (1905-1964), the scale, speed, and force of the transformation were sources of deep conflict and major change.

Although it has never been a “pristine wilderness” per se, the ingenious design of the Catskill and Delaware water supply systems, coupled with the operational expertise and dedication of NYC DEP, has consistently met state and federal regulatory requirements and the daily needs of millions of water consumers for more than a century. This enviable record—repeatedly tested by droughts, floods, and budget constraints——is also the fortuitous result of ecological processes and landscape-scale conservation initiatives. These conservation measures include the CFP, initial land purchases by New York City to protect newly constructed reservoirs, the stewardship of thousands of private forest landowners, and more recent land acquisition by New York City.

After the battering this landscape took throughout the 19th century, the recovery of this forest and living filter is nothing short of remarkable. That said, the ecological legacy of 19th century land and resource use is still evident in many Catskill Mountain streams. Telltale signs include the lack of stable course woody debris,

as well as channel characteristics and bed material (i.e., large stream cobbles, boulders, substantial areas of bed and bank scour and sediment deposition, etc.) that indicate a highly dynamic state. Roads and human activities in stream valleys can exacerbate these unstable and problematic conditions and impact aquatic ecosystems and water quality. Most of the watershed conditions, suite of pollutants, and other challenges faced by the Watershed Protection Program have their roots in historical land and resource uses.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Catskills residents and communities had settled into a state of coexistence with New York City and its water supply system until the events of 1990 inflamed old tensions and generated new concerns. The sweeping social, political, economic and environmental changes of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, and political acumen of watershed communities prevented the repetition of the process used to build the Catskill and Delaware systems and led, with the intervention of Governor George Pataki, to the negotiation of the MOA. Systematically identifying common ground and shared interests, acknowledging and resolving critical conflicts, and working toward a more equitable distribution of costs and benefits—was, and still is, the breakthrough accomplishment of this landmark agreement. Not surprisingly, there were unintended consequences for all parties. Many have been addressed in subsequent agreements and contracts while others are still a source of frustration and concern. A thorough understanding of historical patterns and processes is also needed to effectively address contemporary concerns about community vitality. Recent initiatives (e.g., Pure Catskills, ecotourism and agritourism development, fine art and regional crafts, Internet-based businesses, and others) are linked to many of the same geographic and environmental attributes, and social and economic needs, that marked earlier periods of prosperity and mutually beneficial interdependence between the Catskills region and New York City.

The biophysical and political landscape that supports an irreplaceable water supply system for millions of people, the homes and livelihood of ~50,000 watershed residents, and the large and diverse group of visitors and part-time residents will—as it has for centuries—continue to change and evolve. To the credit of all involved, the continuing, good-faith efforts by watershed communities and NYC DEP to resolve long-standing differences and obstacles to cooperation have strengthened the NYC Watershed Protection Program and the economic vitality of the Catskills. Future success can be fostered, and unintended conflicts and controversies can be minimized, with a shared understanding of ecological, historical and cultural antecedents.

REFERENCES

Applebome, P. 2012. Seeking to lure the crowds again. But hold the borscht. New York Times, July 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/10/nyregion/beyond-borscht-rebranding-the-catskills.html?searchResult-Position=1.

Bennett, R. 1999. The Mountains Look Down: A History of Chichester, A Company Town in the Catskills. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Berkes, F. 2012. Sacred Ecology. Third Edition. New York and London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Canham, H. 2011. Hemlock and Hide: The Tanbark Industry in Old New York. Northern Woodlands, May 27. https://northernwoodlands.org/articles/article/hemlock-and-hide-the-tanbark-industry-in-old-new-york/.

Clemence, S. 2019. An instant community in the Catskills. New York Times, April 12. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/12/realestate/an-instant-community-in-the-catskills.html?searchResultPosition=1.

Cronon, W. 1983. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. 2003 20th anniversary edition. New York: Hill and Wang.

de la Crétaz, A., and P. Barten. 2007. Land Use Effects on Streamflow and Water Quality in the Northeastern United States. London and Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

De Lisser, R. L. 1896. Picturesque Ulster. 1968 reprint edition. C. E. Dornbusch (ed.). Woodstock, NY: Twine’s Catskill Mountain Bookshop.

Delavan, T. 2020. A farmhouse fantasy tucked in the woods of upstate New York. New York Times, February 28. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/t-magazine/farmhouse-upstate-new-york.html?action=click&-module=Editors%20Picks&pgtype=Homepage.

Du Mond, F. L. 1988. Walking Through Yesterday in Old West Hurley. Kalamazoo, MI: Different Dimensions Press.

Duerden, T. 2007. A History of Delaware County, New York: A Catskill Land and Its People, 1797-2007. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Evers, A., R. Titus, and T. Weldner. 2008. Catskill Mountain Bluestone. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Evers, A. 1982. The Catskills: From Wilderness to Woodstock. (Revised Edition). Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press.

Galusha, D. 2016. Liquid Assets: A History of New York City’s Water System. Second Edition. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Hagan, W. T. 2013. American Indians. Fourth Edition. D. M. Cobb (Ed.). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Hughes, J. D. 1996. North American Indian Ecology. Second Edition. El Paso: Texas Western Press.

Irving, W. 1819. Rip Van Winkle. Reprint Edition with illustrations by N.C. Wyeth (1989). Haines Falls, NY: Black Dome Press.

Kudish, M. 2000. The Catskill Forest: A History. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Lasky, J. 2020. A Run on the Catskills. New York Times, June 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/17/realestate/a-run-on-the-catskills.html?action=click&algo=bandit-story&block=more_in_recirc&fellback=-false&imp_id=766807599&impression_id=501718244&index=0&pgtype=Article®ion=footer.

Likens, G. E., F. H. Bormann, R. S. Pierce, J. S. Eaton, and N. M. Johnson. 1995. Biogeochemistry of a Forested Ecosystem, Second Edition. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Lovett, G. M., and H. Rueth. 1999. Soil nitrogen transformations in beech and maple stands along a nitrogen deposition gradient. Ecological Applications 9:1330-1344.

Lovett, G. M., K. C. Weathers, M. A. Arthur. 2002. Control of nitrogen loss from forested watersheds by soil carbon: nitrogen ratio and tree species composition. Ecosystems 5:712-718.

Mann, C. C. 2006. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Vintage/Random House.

Millen, P. E. 1995. Bare Trees: Zadock Pratt, Master Tanner & The Story of What Happened to the Catskill Mountain Forests. Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Press.

NRC (National Research Council). 2000. Watershed Management for Potable Water Supply: Assessing the New York City Strategy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2008. Hydrologic Effects of a Changing Forest Landscape. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Satow, J. 2019. Is the Hudson Valley turning into the Hamptons? New York Times, April 12. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/12/realestate/second-homes-hudson-valley-catskills.html.

Schneider, P. 1997. The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Shorto, R. 2005. The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America. New York: Vintage Books/Random House, Inc.

Soll, D. 2013. Empire of Water: An Environmental and Political History of the New York City Water Supply. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Steuding, B. 1985. The Last of the Handmade Dams: The Story of the Ashokan Reservoir. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Studer, N. 1998. A Catskill Woodsman: Mike Todd’s Story. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press.

Ulster & Delaware Railroad. 1901. The Catskill Mountains: The Most Picturesque Mountain Region on the Globe. London: Forgotten Books.

Vaughn, A. 1995. New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians 1620-1675. Third Edition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Van Valkenburgh, N. J., and C. W. Olney. 2004. The Catskill Park: Inside the Blue Line-The Forest Preserve & Mountain Communities of America’s First Wilderness. Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Press.

Van Valkenburgh, N. J., and C. W. Olney. 2008. History of the Catskill Forest Preserve. https://www.catskill-mountainkeeper.org/history_of_the_catskill_park_and_forest_preserve.

Vu, M. 2015. A guide to Delaware County’s thriving craft culture. New York Times, December 15. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/15/t-magazine/delaware-county-crafts-coffee-whiskey-cheese.html.

Whitney, G. 1994. From Coastal Wilderness to Fruited Plain: A History of Environmental Change in Temperate North America from 1500 to Present. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Woodward, C. 2011. American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Cultures of North America. Penguin Books.

Zelinsky, W. 1973. The Cultural Geography of the United States. Englewood, NJ: Prentice-Hall.