4

Deciding to Reopen Schools

As stated in Chapter 1, decisions around how to reopen schools are among the most complex and consequential of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this chapter, the committee considers the available epidemiological evidence as well as the needs and priorities of U.S. education stakeholders to offer guidance on these decisions. The discussion in this chapter responds to questions 1 and 3 in the committee’s statement of task (see Box 1-1). Taking what is known about decision-making in this moment together with principles from existing guidance documents, we offer a path forward for decision-makers in establishing a clear plan for reopening schools that is based on shared goals and values, ongoing risk assessment, and careful context monitoring.

UNDERSTANDING RISK AND DECISION-MAKING DURING COVID-19

A 1996 National Academies report entitled Understanding Risk: Informing Decisions in a Democratic Society suggests that risk characterization

must be seen as an integral part of the entire process of risk decision-making: what is needed for successful characterization of risk must be considered at the very beginning of the process and must to a great extent drive risk analysis. If a risk characterization is to fulfill its purpose, it must (1) be decision driven, (2) recognize all significant concerns, (3) reflect both analysis and deliberation, with appropriate input from the interested and

affected parties, and (4) be appropriate to the decision (National Research Council, 1996, p. 16).

From the outset of this work, the committee has acknowledged the tremendous challenges associated with characterizing risk such that stakeholders can make cogent, safe decisions around reopening schools in the time of COVID-19. Among other things, decision-makers must weigh competing priorities that include the pressures of different constituent groups, the need to reopen schools to facilitate parents’ full-time return to the workforce, beliefs and perceptions around the import of school for students’ socioemotional and academic well-being, labor demands from every type of staff person working in schools, looming fiscal constraints, and the health and safety concerns of parents.

Beyond this complex set of priorities, the committee recognizes the tremendous physical and emotional strains faced by all stakeholders in the education system: as of this writing, the majority of schools in the United States had been closed for in-person learning since March 2020, and a large swath of parents had been without child care. Beyond having to engage with state and local virus mitigation strategies (e.g., stay-at-home orders, mandated use of face coverings) and witnessing the tremendous loss of life experienced by many communities, critical stakeholders face the very real threat of “decision fatigue.”1 The committee also recognizes that many communities of color have joined together to lead historic protests toward advancing racial justice in the United States, and concerns about reopening schools will necessarily take place against that backdrop.

The public health risk from COVID-19 is the reason that schools closed in Spring 2020. As the start of the 2020–2021 school year approaches and districts and schools contemplate reopening for in-person activities (whether fully or partially) it is important to understand that it will not be possible to prevent transmission entirely. The increased contact that will occur when people come together in the school, even with many mitigation measures in place, will more than likely lead to new cases of the virus. The question is not a matter of whether there will be cases of SARS-CoV-2 in schools, but what the spread of the virus will look like once cases begin to emerge. Stakeholders need to understand this risk and be willing to move forward with reopening for in-person learning despite it.

In light of this complex constellation of considerations, the committee notes that decisions about reopening schools are likely to be more iterative and ongoing. As circumstances change and understanding of COVID-19

___________________

1 Decision fatigue is the idea that the act of making choices repeatedly can lead to depletion of the decider’s psychological resources, which can lead to less optimal choosing over time (Vohs et al., 2008).

grows, states, districts, and schools will likely need to decide and redecide not only whether to reopen but also how to know when it may be necessary to shut down again. Later in this chapter, we outline a framework for advancing that iterative decision-making by relevant stakeholders in a given community.

EXISTING GUIDANCE FOR SCHOOLS

As part of its charge, the committee reviewed the rapidly emerging guidance documents related to reopening K–12 schools. While a robust analysis of the content of these documents is beyond the scope of our charge (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1), we did note a few themes in this guidance related to who should make decisions about reopening schools and how best to make those decisions.

One important issue the committee identified—one also highlighted by a number of presenters during the committee’s information-gathering sessions—is that the majority of state-level guidance documents do not explicitly call on districts to reopen schools, but are framed as a series of questions for districts to ask while making decisions about reopening. While this approach to providing guidance does allow for regional variation and sensitivity to contextual factors, it also leaves school districts with a tremendous responsibility for determining how to meet their obligations to students, families, and staff. Many school districts are left without a clear roadmap for understanding just what kind of schooling they are responsible for as the pandemic continues with respect to both academic experiences and the many social services schools are required to provide (see Chapter 3). In addition, placing the full burden on districts leaves open the possibility that if a student, a staff person, or someone in the community contracts COVID-19 in the school, the district will be held responsible.

Guidance provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—in particular, the “decision tree” included with its formal guidance—serves as the basis for most state-level documents on school reopening. A challenge of the CDC decision tree is that it states that hygiene, cleaning, and physical distancing should be implemented “as feasible.” Districts are left to make judgment calls about the extent to which they should push to implement all of the recommended strategies and what the consequences might be of relaxing one or the other of those strategies. Some districts may have ready access to experts in infectious disease and public health who can provide input for these decisions, but others do not. For example, many rural communities have either a small or no local health department, and personnel in those agencies may have limited expertise in infectious diseases (Cheney, 2020; Eisenhauer and Meit, 2016).

A close, ongoing partnership between education leaders and departments of public health that starts during planning for reopening is essential.

Such a partnership is particularly important for continuing to monitor the incidence of COVID-19 in schools. The need for this partnership, however, raises the question of how communities where both the schools and the public health infrastructure are under-resourced will be able to maintain the health of the community when schools reopen.

In looking across the guidance documents, the committee felt it was especially important to point out the challenging reality facing school districts that are now responsible for making the majority of decisions related to school reopening. As noted above, this local decision-making is reasonable insofar as it accounts for the significant variation in the spread and prevalence of COVID-19 across different parts of a given state. Further, districts differ in their goals for schooling; as we discuss below, districts across a state are likely to have different supports in place for distance learning models. Different communities in the same state will inevitably have different kinds of needs associated with in-person education. That said, Chapter 3 describes the reality that districts within the same state are likely to have significantly different resources (financial, human capital, etc.) to put toward reopening schools. In light of the fiscal challenges many school districts will face in the 2020–2021 school year, states will need to have a role in ensuring an equitable distribution of resources and expertise so that districts can implement the measures required for a strategic reopening in their local contexts.

A FRAMEWORK FOR DECIDING WHEN TO REOPEN SCHOOLS FOR IN-PERSON LEARNING

Given the range of stakeholders invested in decisions around reopening schools, the committee recognizes that those decisions and processes will be complex. In most cases, decisions about reopening are within the purview of the district superintendent and school board. In this context of multiple stakeholders and often conflicting priorities, the committee recognized that a data-driven, real-time decision-making framework can help stakeholders break down the decision-making process into manageable, informed steps.

To articulate such a framework, the committee turned to testimony provided as part of our information-gathering process by epidemiologist and professor of integrative biology Dr. Lauren Ancel-Meyers of the University of Texas. The University of Texas COVID-19 Modeling Consortium Framework (Box 4-1) can be used in pursuit of three main objectives: (1) help decision-makers establish goals for reopening and the levels of risk they are willing to assume in pursuit of those goals, (2) determine what policy and mitigation strategies are reasonable and desirable, and (3) establish a protocol for continuous feedback through data monitoring.

The University of Texas COVID-19 Modeling Consortium Framework, although not specifically developed for school reopening decisions, supports education stakeholders in working with public health officials to continually make and remake decisions based on data as they become available (for more information on who should make these decisions, see the following section). The steps in the decision-making process, outlined in Box 4-1, are described below.

First, the framework directs decision-makers to establish values, goals, and priorities for reopening schools. For example, does a community want students to attend school in person because parents are in overwhelming need of child care? Or are stakeholders determined to ensure continuity of learning by any available means, including virtual or distance learning modalities? Ancel-Meyers suggests that once those goals have been established, decision-makers can weigh the goals against the level of risk they are

willing to assume: What is the threshold of case counts this community is willing to accept before closing in-person facilities? What levels of absenteeism are acceptable to keep a majority of students in classrooms?

In step 2, stakeholders and decision-makers review mitigation strategies and policy options for schools. It is at this point in the process that stakeholders will need to be explicit about what the constraints are on the various policy options on the table: for example, schools and districts may need to conduct an assessment of how robust the current distance learning infrastructure is for supporting at-home learning. Stakeholders may also want to consider local variability in seasons as they make plans to support fresh air exchange in classrooms, or even consider whether outdoor learning is a realistic possibility.

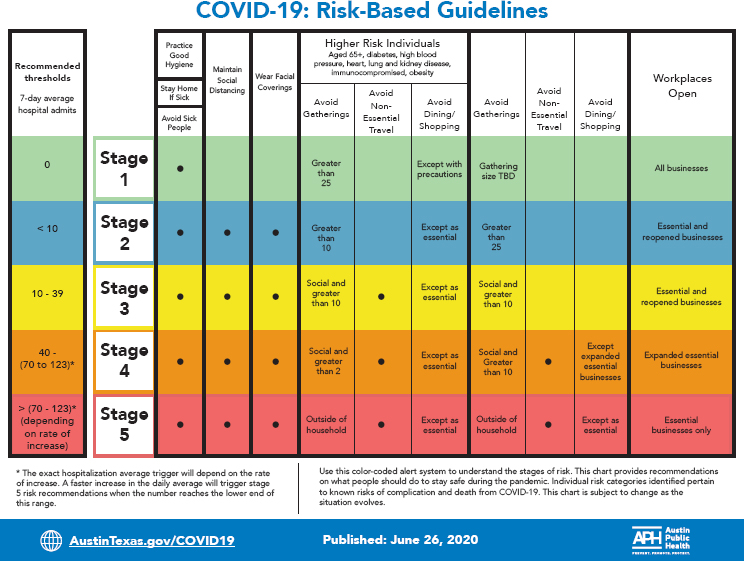

Finally, stakeholders will need to establish protocols for collecting and monitoring data related to the COVID-19 context in the community. In this process, relevant decision-makers establish clear thresholds for what those data mean; for example, once a school sees X number of cases, it will enact Y policy. Figure 4-1 illustrates how the city of Austin, Texas, is operationalizing this staged approach to reopening schools and businesses.

In the case of Austin, Texas, thresholds for the staging of community reopening are determined by using the number of 7-day average hospital admissions to understand the level of ongoing risk posed by COVID-19. In the red stage (more than 70 long-term hospital admissions), the city is open only to essential businesses, and mitigation strategies for all individuals (masks, physical distancing) are in place, regardless of their personal risk status. As case counts decline, the city moves from Stage 5 down to Stage 1. As the city proceeds through stages, mitigation strategies slowly ease—first for lower-risk individuals and then for higher-risk individuals—and more businesses open up. If case counts increase, the city can move back to an earlier stage of intervention, depending on the level of COVID-19 risk.

The state of Oregon is using a similar approach for the reopening of schools and businesses (https://govstatus.egov.com/reopening-oregon#baseline), with counties submitting plans and data to the state to receive approval for moving through different phases of reopening. Counties must demonstrate progress on seven indicators: declining prevalence of COVID-19, minimum testing requirements, clear and actionable plans for contact tracing, identified locations for safe isolation and quarantine, a clear plan for keeping workers safe and healthy, sufficient health care capacity, and a sufficient supply of personal protective equipment. As progress on these indicators is demonstrated, restrictions on businesses and individual behaviors ease.

Districts, local health officials, and communities could operationalize similar approaches in establishing plans for reopening schools that leverage potential mitigation strategies and policies together with ongoing data monitoring. Chapter 5 details the mechanisms that need to be in place to

SOURCE: austintexas.gov/COVID19.

ensure that states, districts, and schools can carry these plans forward in implementing the reopening of schools, and Appendix C provides a number of examples for how districts are planning to reopen in Fall 2020.

APPROACHES TO COLLECTIVE DECISION-MAKING

As a process for deciding whether schools should reopen is established, schools and districts will need to ensure that the decisions made reflect their community’s priorities. To this end, school districts and communities must be willing to listen and co-plan with community members in order to engage all relevant constituent groups.

In May 2020, the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) released a “playbook” for enhancing or establishing a local task force to address issues related to COVID-19. This document describes in depth both what kinds of stakeholders should be involved in decision-making (see Box 4-2) and a series of five action items that the task force should take up (discussed later in this chapter). After reviewing this document and considering expert

testimony provided as part of our information-gathering process, the committee agrees that community engagement in decisions related to reopening can help ensure that the divergent concerns of education stakeholders are, at a minimum, brought to light and taken into account. In the absence of this kind of community input, decision-makers risk the possibility that school staff and families will not understand the values or logic behind certain choices, potentially leading some stakeholders to divest from schools altogether.

In particular, districts can deepen partnerships with families and communities by involving them in planning for the reopening of schools; the decision to reopen; the preparation of students for learning; and implementation of newly required policies, procedures, and plans. This involvement is particularly important for families and communities historically marginalized by public systems, which often experience the greatest impact from inequitable schooling.

The SREB (2020) report identifies five major action items for a community task force once it has been assembled:

- Define the problem the task force will address, and establish a clear scope and purpose to guide the group’s work.

- Define a timeline for the work of the task force, and communicate it to task force members and other shareholders.

- Identify and secure the participation of task force members, ensuring that the membership is balanced and aligns with the group’s communicated purpose.

- Gather background information and secure available resources.

- Establish a multifaceted communication plan.

Attending to these items up front makes it possible to then focus on the actual work of making decisions related to reopening schools.

The committee notes that while the precise details of both who is involved in the planning processes and the processes themselves are likely to change depending on local needs, an inclusive process whereby stakeholders are asked to be explicit about their goals, values, and priorities will yield long-term benefits when challenging real-time decisions must be made. The committee also notes that a truly inclusive process for decision-making is not merely about ensuring diverse perspectives at the table, but also about conversations designed such that multiple parties can truly engage. Task forces may want to consider providing supports for families with first languages other than English to ensure that their voices, priorities, and interests are included in the decision-making process. Task forces may also want to leverage partnerships with community organizations to help in assessing the comfort of families with returning to school, as well as in making informa-

tion accessible to diverse families through such communication strategies as live-streamed meetings and public (socially distanced) town halls.

Additionally, task forces need to consider transparent communication of the reality that while measures can be implemented to lower the risk of transmitting COVID-19 when schools reopen, there is no way to eliminate that risk entirely. It is critical to share both the risks and rewards of different scenarios, and to consider interventions that can be implemented to communicate to families that every effort is being made to keep their children safe in schools. While all stakeholders will not necessarily agree with the final decisions about when and how to reopen schools, an inclusive process will help build trust in school leadership so that decisions can be implemented quickly should conditions change.

MONITORING COVID-19 CONDITIONS

Schools and districts will need to work with their state or local health departments to plan for the monitoring and evaluation of epidemiological data to iteratively assess disease activity in the county (or relevant area). Indicators of particular interest include the number of new cases diagnosed, the number of new hospitalizations and deaths, and the percentage of diagnostic tests that are positive. Schools also will need to monitor absenteeism and alert public health officials to any large increases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020a). According to the CDC’s school decision tree, communities with substantial community transmission may need to implement extended school closures. For this reason, the committee notes that it is especially important that decisions about what constitutes substantial community transmission and under what conditions schools would again close will need to be outlined before the school year begins. Finally, stakeholders tasked with monitoring data may also want to consider how to ensure that the data are disaggregated by race, class, and (depending on the size of the school or district) zip code. Given what is known about the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on under-resourced communities, disaggregated data may offer targeted insight into how to approach mitigation equitably.

One particularly effective strategy for monitoring COVID-19 conditions is to implement a testing program that assists in screening for positive cases. Currently, the CDC recommends that schools refer the following individuals to health care officials for further evaluation: (a) individuals with signs or symptoms consistent with COVID-19, and (b) asymptomatic individuals with recent known or suspected exposure to SARS-CoV-2 to control transmission. School staff are not currently expected to perform tests themselves, although they may serve that purpose in their capacity in school-based health care centers. Finally, the CDC does not recommend

universal testing of students and staff (i.e., testing everyone even if asymptomatic), because it is not currently understood whether or not a universal testing program contributes to a reduction in transmission (CDC, 2020c). Further, as the CDC guidance on testing and tracing notes,

Implementation of a universal approach to testing in schools may pose challenges, such as the lack of infrastructure to support routine testing and follow up in the school setting, unknown acceptability of this testing approach among students, parents, and staff, lack of dedicated resources, practical considerations related to testing minors and potential disruption in the educational environment (CDC, 2020c).

To the extent that testing is part of a school’s monitoring plan, it may consider partnering with a local health department to implement a contact tracing program. Contract tracing involves identifying individuals who come into contact with others who have tested positive for COVID-19, and asking affected individuals to voluntarily quarantine for 2 weeks to curtail transmission. Although the combination of robust testing and contact tracing programs can serve as a useful strategy in limiting transmission, it may require a substantial investment of local resources. As we discuss in detail in Chapter 5 of this report, schools and districts will need to the weigh the benefits of testing and tracing against the costs and utility of the numerous other mitigation strategies that will need attention.

Monitoring will need to occur at the individual level as well. All staff and parents of children should have initial and periodic training on basic infectious disease precautions, including the identification and management of symptomatic personnel and students, and instructions to remain at home if symptoms do appear. The CDC has guidance for parents (CDC, 2020b).

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 4.1: Decisions to reopen schools for in-person instruction and to keep them open have implications for multiple stakeholders in communities. These decisions require weighing the public health risks against the educational risks and other risks to the community. This kind of risk assessment requires expertise in public health, infectious disease, and education as well as a clear articulation of the values and priorities of the community.

Conclusion 4.2: A decision-making framework andan inclusive process for making decisions can help support community trust in school and district leadership so that decisions can be implemented quickly throughout the school year.

Conclusion 4.3: Education leaders need to have a way to monitor data on the virus so they can track community spread. If there is substantial community spread, schools may need to close for in-person learning. Decisions about what constitutes substantial community transmission and under what conditions schools would again close need to be outlined before the school year begins.