5

Reducing Transmission When School Buildings Are Open

The decision to reopen school buildings also involves developing a plan for how schools will operate once they are open and how to balance minimizing risk to students and staff while being realistic about cost and practicality. It is important to bear in mind that in order to protect the health of staff, students, their families, and the community, schools will not be able to operate “as normal.”

This chapter addresses areas that districts must consider when they are developing plans for reopening: implantation of mitigation strategies, creating a culture for maintaining health, and what to do if someone in the building tests positive for the virus. We begin with an overview of the “hierarchy of controls,” a framework for approaching environmental safety in workplaces that is useful for organizing implementation plans. This is followed by a discussion of the most common mitigation strategies for reducing the transmission of COVID-19 in light of existing epidemiological data, published guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and practicality in school settings. We then provide brief commentary on what to do when someone tests positive. The chapter ends with the committee’s conclusion with respect to mitigation strategies for schools. This chapter responds to questions 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the statement of task (see Box 1-1).

It is important to emphasize that this chapter is not meant to replace the guidance issued by the CDC or by states. Rather, the committee offers considerations intended to help districts think through their implementation plans based on the scientific community’s understanding of transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as of July 6, 2020. In addition, the committee

does not discuss the steps needed to safely reopen buildings that have been closed for a long period of time (e.g., the safety of the water or heating, ventilation, and air conditioning [HVAC] systems). Districts should follow guidance on this provided by the CDC.

IMPLEMENTING MITIGATION STRATEGIES

As discussed in Chapter 2, and noted in the CDC guidance, COVID-19 is mostly spread by respiratory droplets released when people breathe, talk, cough, or sneeze. The virus may also spread to the hands from a contaminated surface and then to the nose, mouth, or eyes, causing infection. This means strategies that limit spread of and exposure to the droplets are the most important for mitigating transmission. As the CDC notes, the risk of transmission in schools is highest when there are “full sized, in-person classes, activities, and events. Students are not spaced apart, share classroom materials or supplies, and mix between classes and activities.” Risk is lowered when “groups of students stay together and with the same teacher throughout/across school days and groups do not mix. Students remain at least 6 feet apart and do not share objects.”

The guidance provided by the CDC identifies numerous strategies that can be implemented in school to lower risk of transmission. Implementing the full set of strategies may be difficult in many districts due to costs, practical constraints, and the condition of school buildings. As noted in Chapter 4, the decision tree provided by the CDC recognizes these constraints in saying that strategies be implemented “as feasible.” While this gives districts flexibility in developing their plans, it also leaves district leaders with the challenge of making judgment calls about how much they should push to implement all of the recommended strategies and what the consequences might be of relaxing some of the strategies.

The major challenge for everyone trying to make judgments about the effectiveness of the various strategies in schools is that the evidence about COVID-19 is still emerging. As a result, the committee was not able to provide strong, definitive guidance on the relative effectiveness of each of the various strategies schools are considering to limit the spread of the virus. However, the committee does offer commentary on the strategies that are especially important to implement well based on current understanding of the disease and lessons learned from research on other viruses.

In this section, the committee identifies a set of key mitigation strategies that schools could implement to reduce the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. To develop this set of strategies, the committee referred to the CDC guidance for schools as well as guidance from states in conjunction with committee members’ understanding of evidence about transmission. In addition, the committee heard expert testimony from epidemiologists and

infectious disease doctors who offered their perspectives on which strategies are most promising and which are less likely to be effective (for more information on this process, see Appendix A). We also considered existing infrastructure in schools and additional cost to implement.

The Hierarchy of Controls

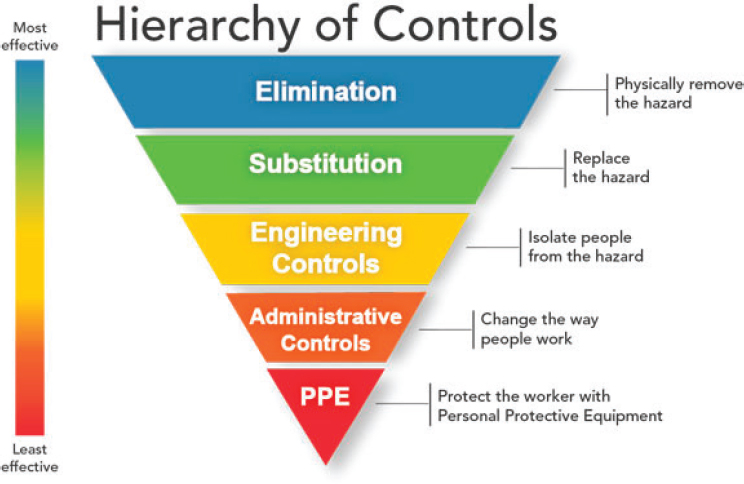

To organize the discussion of strategies, the committee used the hierarchy of controls framework. The hierarchy of controls, an approach to environmental safety, is a framework used in many workplaces to prioritize strategies for minimizing people’s exposure to environmental hazards (Figure 5-1). This hierarchy structures protective measures according to five levels:

- Elimination

- Substitution

- Engineering

- Administrative

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Generally, strategies that fall within the levels at the top of the hierarchy are viewed as more effective than those within the levels at the bottom.

SOURCE: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2015.

This means that when this framework is used, the top levels—elimination, substitution, and engineering controls—are given higher priority. In the context of an infectious disease, however, which strategies need to be prioritized at each level is determined by the route of transmission of the disease. A disease that is spread only by direct physical contact requires different engineering or administrative controls relative to a disease that is spread through droplets. The challenge in the case of the current pandemic is that the transmission of COVID-19, particularly the role of children in transmission, is still not entirely understood (see Chapter 2).

Applying the hierarchy of controls to COVID-19 and schools, elimination and substitution do not apply to school buildings as they reopen. Elimination would be complete control of the virus or a widely distributed vaccine. Substitution means replacing a hazard (in this case the virus) or a hazardous way of operating (being in school) with a nonhazardous or less hazardous substitute. Since COVID-19 cannot be “replaced,” the option here is to adopt new, safer processes—for example, moving to distance learning. As discussed in Chapter 3, however, this option may have negative consequences for children, families, and communities if implemented for long periods of time.

Engineering controls eliminate a hazard before an individual comes into contact with it. In the case of COVID-19, such strategies could include improving ventilation, erecting barriers around an area (for example, for front office staff), changing the configurations of classrooms to allow for physical distancing, and performing regular cleaning.

Administrative controls change the way people work. In the context of schools, this means eliminating large gatherings, creating groupings of students and patterns of movement that limit contact with other people, instituting handwashing routines, emphasizing coughing and sneezing etiquette, and providing training in the new routines. The majority of the CDC guidelines fall into this category of controls. Finally, PPE, masks and face shields, is lowest in the hierarchy of controls.

The best way to manage the risk of viral spread in schools is to implement strategies at all three levels (engineering, administrative, and PPE). Given the current context, however, with only an emerging understanding of transmission and how it relates to children, it is difficult to provide evidence-based guidance as to which specific strategies at each level will be most effective. One potential pitfall of implementing strategies based strictly on the hierarchy of controls is that doing so could drive schools to focus primarily on implementing all possible strategies at the engineering level first, on the assumption that this is the most effective way to limit exposure. However, the emerging evidence about COVID-19 suggests that several strategies at the administrative level—including creating routines that allow for physical distancing, eliminating large gatherings, and stress-

ing handwashing—are very important for limiting transmission (see Chapter 2 for more discussion of transmission). In addition, there is increasing evidence that wearing masks can lower transmission. The following section highlights strategies that appear to be especially important to implement or that receive substantial attention in districts’ plans (see Table 5-1 for a summary of the strategies).

Personal Protective Equipment

Ideally, all students and staff, including elementary children, should wear fabric face coverings or surgical masks. For teachers and staff, N95 masks would be most effective, but would be difficult to teach in. Surgical masks offer better protection than cloth masks, but may not be available. Requiring only staff to wear masks is less effective because the fabric face coverings recommended by the CDC do not fully protect the wearer from droplets. Rather, the masks are most effective for reducing spread from people who are infected by containing droplets. Children in early elementary grades, especially kindergartners, may have difficulty complying with mask usage. Nonetheless, efforts should be made to encourage compliance. (Strategies for encouraging mask use and other new health behaviors are discussed in a later section.)

Face shields have been recommended by some researchers as an alternative to face masks, and may be an option that would allow students to see teachers’ faces (Perencevich, Diekema, and Edmond, 2020). However, the relative effectiveness of using face shields in lieu of fabric masks is unknown, and neither the CDC nor the World Health Organization has commented on this as an option for control of SARS-CoV-2 in the community. Considering that face shields allow droplets and aerosols to escape into the surrounding air, it is unlikely that face shields alone can be as effective as other types of masks.

Implementing all of the COVID spread mitigation strategies fully and faithfully will maximize protection of students and staff. However, districts and schools have limits on staff, time, and resources. Additionally, each school and school community will have unique qualities and the public health conditions in communities will vary. Table 5-1 is provided for stakeholders and districts to use to evaluate how to apply mitigation strategies in their schools given the limits to their resources and what is now known about the mechanics of how these mitigation strategies affect the spread of the virus.

TABLE 5-1 Summary of Mitigation Strategies

| Strategy | Role in limiting transmission | Considerations for implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Wearing masks (surgical, fabric) | The vims is spread through respiratory droplets from breathing, talking, coughing and sneezing. The mask catches the droplets before they can spread. | Requiring masks for all students and staff is most effective. |

| Hand-washing | Droplets containing the vims can spread to hands from coughing, sneezing or from surfaces. If a person then touches their mouth, nose, or eyes they may become infected. Handwashing removes the vims. | Soap and water is most effective. Hand-sanitizer is appropriate to use if soap and water are not available. Minimum times for hand washing — before and after eating, after using the restroom. |

| Physical distancing — Maintaining 3 to 6 feet between students and staff | When people are in close contact they can easily breathe in droplets containing the vims that other people have exhaled. Most droplets will fall to the ground within 3-6 feet of being exhaled. | How this is implemented will depend on the number of students in the school and the size of classrooms. The key is maintaining sufficient space between students and between students and the teacher. There is no evidence about the relative effectiveness of different ways of implementing physical distancing in schools. |

| Eliminating large gatherings | If a person is sick, large gatherings with close contact mean that many other people may be infected. | This includes eliminating assemblies, large sports events, and large numbers of students in common areas (cafeteria, hallways, entryways) |

| Creating cohorts (one teacher stays with the same group of students) | Smaller groups of students in a classroom allow for more distance between people. In addition, limiting contact with many other people, cuts down on possible exposures. | Members of the cohort do not mix with the rest of the school. The teacher should also have minimal contact with students and other staff outside of the cohort. |

| Cleaning | Droplets can land on surfaces and remain active for 1-3 days. If a person touches the surface with their hands and then touches their mouth, nose or eyes, they can contract the vims. | Regular cleaning is important to eliminate the vims on surfaces. Routine cleaning with appropriate disinfectant is sufficient. Cleaning is particularly important for high touch areas and shared materials. |

| Ventilation | While most droplets containing the vims fall out of the air, some can stay suspended. If enough suspended droplets accumulate they could be breathed in by occupants. When fresh air is added to a room where vims is present, the amount of vims is diluted or eliminated. | Small rooms with poor ventilation are likely to increase risk of transmission. Open windows and doors to increase circulation of outdoor air as much as possible. Moving classroom activities out-of-doors is also an option for improving ventilation. |

| Air filtering | Mechanical heating, cooling and ventilation control and regulate the amount and quality of air in buildings for humidity, temperature and particulates. For efficiency, some systems recirculate the indoor air as much as possible to reduce the energy costs of treating outside air. If there are droplets containing the vims in the air, recirculation could spread COVID within a building. Upgraded filters can remove droplets containing the vims from the air. | To provide maximum protection, upgrade the filters used in the HVAC system, increase the fresh air intake, and increase the level of humidity. |

| Temperature and symptom screening | The intent is to identify individuals who have COVID-19 and prevent them from bringing the vims into the building. | There is increasing evidence that people are contagious before they show symptoms. This means the considerable time and costs to screen all students before entering buses or schools may be of limited value for identifying COVID cases. Studies in airports show limited value. However, parents should know the symptoms for COVID-19 and screen their children and household for them each day before sending children to school. |

Administrative Controls

As noted in the previous section, many of the mitigation strategies outlined by the CDC fall into the administrative control level of the hierarchy of controls. We have identified a set of these as particularly important to implement, given the way COVID-19 is transmitted: handwashing, physical distancing, cohorting, and avoiding use of shared instructional materials or equipment.

Routines for Handwashing and Hygiene

The CDC (2020) recommends that individuals wash their hands

- “Before, during, and after preparing food

- Before eating food

- Before and after caring for someone at home who is sick with vomiting or diarrhea

- Before and after treating a cut or wound

- After using the toilet

- After changing diapers or cleaning up a child who has used the toilet

- After blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing

- After touching an animal, animal feed, or animal waste

- After handling pet food or pet treats

- After touching garbage

- After you have been in a public place and touched an item or surface that may be frequently touched by other people, such as door handles, tables, gas pumps, shopping carts, or electronic cashier registers/screens, etc.

- Before touching your eyes, nose, or mouth because that’s how germs enter our bodies.”

To make these recommendations feasible in a school setting, the committee observes that at a minimum schools will have to provide handwashing opportunities after using the restroom and before eating, along with making alcohol-based hand sanitizer available in classrooms and shared spaces such as a gymnasium or cafeteria. Providing frequent opportunities for handwashing may be especially difficult in school buildings with limited or poorly functioning restroom facilities. In these cases, hand sanitizer can be used, if improving or repairing restrooms is not possible.

Physical Distancing

Physical distancing (also called social distancing) is a key strategy for limiting transmission. Fundamentally it involves avoiding close, physical contact with other people. The CDC recommends that people keep at least 6 feet away from people outside of their household.

In the context of schools, physical distancing may require many changes to routines and use of space. Classrooms will need to be organized to allow students and the teacher to maintain distance from each other. It may be necessary to limit the number of students in the classroom or to move instruction to a larger physical space. Different staffing models will likely need to be considered depending on the particular strategy employed. In schools that are already overcrowded, creating space for physical distancing may be difficult.

Another important aspect of physical distancing is limiting large gatherings of students, such as in the cafeteria, in assemblies, or for indoor sports events. This also means avoiding overcrowding at school entrances and exits at the beginning and end of the school day, potentially by staggering arrival and departure times. The specific strategies will depend on the characteristics of each school building and the number of students in attendance.

Cohorting

Cohorting denotes having the same small group of students (10 or fewer) stay with the same staff as much as possible. This model has been used in some other countries that have reopened school buildings. For example, in Denmark class size was limited to 10–11 students to allow distancing between students and staff were limited to working with 1 or 2 classes (Melnick et al., 2020).

A benefit of this approach is that it limits the number of different people with whom any single individual has contact. This approach is likely easiest to implement in elementary schools, because elementary classrooms are already organized such that one teacher works consistently with the same group of students. In the upper grades, students typically move between classes, often mixing from class to class. Of interest, the use of small cohorts for middle school students may be more developmentally appropriate than the usual structure of students changing classrooms for every class because it offers an opportunity for developing a closer relationship with the teacher (Eccles et al., 1993).

In planning for different versions of cohorting, it is important to keep in mind that the main goal is to limit the exposure to others of all individuals, including both teachers and the students. Thus models whereby a

teacher sees multiple cohorts of students in the same day, or across several days, may not meaningfully reduce risk for the teacher. To limit the amount of contact each teacher has with multiple different students, schools could consider creative uses of virtual instruction. For example, a cohort of students might be physically with a lead teacher, while teachers of specific subjects would join the class virtually for a period of time.

Avoiding Use of Shared Materials and Equipment

Because of the risk of transmission from surfaces, it is important to minimize shared objects such as manipulatives used in teaching, art supplies, or technology. If they are shared, they need to be cleaned between uses (see section on cleaning below).

Engineering Controls

Key strategies at the engineering control level are cleaning, ventilation and air quality, and temperature and symptom screening. However, it is important to stress that implementing these strategies only is unlikely to limit transmission enough to prevent students or staff from getting sick.

Surface Cleaning

Regular cleaning is important, but schools will find it nearly impossible to clean as frequently as would be needed to ensure that surfaces remain completely virus-free at all times. Emerging evidence suggests that the virus persists on most hard surfaces for 2–3 days and on soft surfaces for 1–2 days (van Doremalen et al., 2020). The CDC has guidance on cleaning and disinfecting available that schools can use to guide their procedures (CDC, 2020). At minimum, surfaces should be cleaned and disinfected nightly.

Even with regular cleaning, it is important to minimize contact with shared surfaces such as manipulatives or other hands-on equipment in the classroom. Strategies for minimizing transmission via shared surfaces include assigning equipment to individual students to prevent multiple users, and disinfecting items between users. Use of soft-touch items that are difficult to disinfect should be minimized.

Cleaning is especially important when someone in the school building becomes sick while on site and/or tests positive for COVID-19. In these cases, the protocols laid out in the CDC guidance should be followed, including closing off space(s) where the infected person was for 24 hours if possible before cleaning and disinfecting. In many cases, this may include shared restrooms.

Air Quality and Ventilation

As noted above, the primary mechanism of transmission of SARSCoV-2 is through respiratory droplets traveling through the air. While many of these droplets are heavy and drop out of the air, some may remain airborne for a longer period of time as aerosols (very small, floating droplets).

In a small space with poor ventilation, the droplets and aerosols in the air may accumulate enough to create a risk of infection. For this reason, it is important to ensure that classrooms and other spaces in the school building are well ventilated. Ventilation systems should be operating properly and, when possible, circulation of outside air should be increased, for example by opening windows and doors. Also, use of face masks will limit the number of droplets and aerosols that are released into the air.

Maintaining sufficient ventilation may be difficult in classrooms with windows that do not open, or in schools with poorly functioning ventilation systems. As noted in Chapter 3, poor air quality and outdated HVAC systems may be particularly problematic for under-resourced schools.

A recent report from the Harvard School of Public Health (Jones et al., 2020) identifies key strategies for ensuring air quality and proper ventilation. The report emphasizes the importance of bringing in outdoor air to dilute or displace any droplets containing the virus that may be present in the air. They also recommend avoiding recirculation of indoor air, increasing filter efficiency, and supplementing with portable air cleaners. The report’s authors also stress the importance of verifying the performance of ventilation and filtration through testing and working with outside experts. These additional strategies represent additional costs to schools, but they may be especially important for older school buildings with outdated HVAC systems, or for buildings with limited ventilation.

Temperature and Symptom Screening

Temperature and symptom screening is mentioned in two places in the CDC decision tree. While it is important to be sure that people who are infected do not enter the building, there is mounting evidence that people may be contagious before they show symptoms of COVID-19. This means that screening may not identify all individuals who pose a risk for bringing the virus into the school. In addition, temperature screening alone is less likely to identify individuals than temperature and symptom screening.

Applying the Strategies to Transportation

Many districts around the country use transportation systems, such as buses, to enable safe, reliable passage to school for children. As noted in

Chapter 3, about 33 percent of students in the United States ride a school bus to get to school. A major concern for school districts is that it is impossible to transport students to schools in a school bus while maintaining a 6-foot distance between children. If buses were to reduce capacity in accordance with physical distancing guidelines, they would likely be able to transport only 8–10 students per bus at a time. Given this constraint, epidemiological wisdom points to limiting the use of buses. When their use is necessary, however, strategies include avoiding seating students in the two seats closest to the driver, disinfecting shared surfaces (e.g., hand rail, buttons) after each stop if possible, disinfecting all surfaces between trips, and for HVAC systems, using the highest setting and changing filters regularly.

A small number of students, about 2 percent, across the country, take public transportation to school. This poses additional risks of exposure over which districts have little control.

The Cost of Mitigation

The cost of implementing all of the suggested strategies is very high. The Council on School Facilities estimates that the total cost for schools nationwide could be $20 billion. A recent estimate reported by EdWeek (Will, 2020) suggests that for the average district, the cost of implementing the strategies might be as much as $1,778,139 for the 2020–2021 school year (see Box 5-1 for the breakdown of estimated costs for an average district). This estimate is based on costs for a district with 3,269 students, 8 school buildings, 183 classrooms, 329 staff members, and 40 school buses operating at 25 percent capacity.

The actual costs will vary by school district depending on regional prices, economies of scale (how much volume districts can purchase), and the availability of labor and goods necessary to comply with recommended physical distancing and cleaning protocols. The model for the transportation costs assumes running buses at 25 percent typical capacity to adhere to physical distancing guidelines. The costs do not include the extra funds needed to provide staff and students with training in the new protocols.

These extra costs for reopening for in-person learning and limiting transmission of the virus among students and staff are coming at a time when state budgets are shrinking because of the economic impact of the pandemic. This means that education budgets are being cut, making it even more difficult for districts and schools to find the funding to implement all of the necessary measures. As a result, districts will have budgetary reasons for only partially implementing the CDC’s recommended strategies as well as practical ones. However, as mentioned in Chapter 4, districts and schools

have little guidance on how to select which strategies might be most effective for limiting the spread of COVID-19.

Mitigation Strategies in International Contexts

As K–12 schools in the United States move toward reopening for in-person learning, it may become possible to learn about the effectiveness of strategies for mitigating the transmission of COVID-19 from other countries that have reopened their school buildings. Although research on these strategies in international contexts is nascent, understanding how other school systems have managed the crisis may provide insight into what schools in the United States can do to mitigate transmission as they reopen. Table 5-2 provides a snapshot of the strategies and methods other countries have used when reopening their schools to in-person learning.

CREATING A CULTURE FOR MAINTAINING HEALTH

The suite of strategies for limiting transmission during the pandemic will create many new routines that students and staff will need to follow and behaviors they will need to adopt. These measures will be most successful if the majority of people follow them consistently. As the CDC guidelines point out, this will require that all staff and students learn about the strategies, why they are important, and how to adhere to them as well as possible. The CDC also recommends the use of signage to remind students of the strategies and to illustrate how they can move through the building in ways that maintain physical distancing.

Providing training for all staff and students is an important part of ensuring that the strategies are implemented properly. The training should be provided by local public health officials possibly in collaboration with the school nurse. Staff and families should also receive training in how to identify symptoms and on criteria for when they, or their children, should stay home because they are sick.

Even with training and signage, staff will need to help students continue to follow these strategies. The fact that staff will need to monitor and enforce the guidelines around mask wearing, physical distancing, and handwashing opens up the possibility that patterns of enforcement of the new measures will follow the same trends that are seen in school discipline more generally. Should this be the case, Black students, boys, and students with disabilities will be particularly vulnerable to potentially harsh responses if they fail to follow the strategies consistently (Anderson and Ritter, 2017; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2018). To guard against this, positive approaches to encouraging adherence to the strategies are preferred over punitive ones.

TABLE 5-2 Summary of Health and Safety Practices in International Contexts

| China | Denmark | Norway | Singapore | Taiwan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Gradual reopening since March | Opened April 15 for children up to age 12 | Opened April 27 for Grades 1–4 | Opened until April 8, then closed due to non-school-related outbreak | Never fully closed; local, temporary closures as needed |

| Health screening | Temperature and symptoms checks at least twice daily | Temperature and symptoms checks on arrival | Temperature and symptoms checks on arrival | Temperature and symptoms checks twice daily | Temperature and symptoms checks on arrival |

| Quarantine and school closure policy | Quarantine if sick until symptoms resolve | Stay home 48 hours if sick | Stay home if sick until symptom-free 1 day | Quarantine required and legally enforced if one has had close contact with a confirmed case; school closes for deep cleaning if case confirmed | Class is suspended 14 days if one case confirmed, school suspended 14 days if 2+ cases |

| Group size and staffing | Class size reduced from 50 to 30 in some areas of the country | Class sizes reduced to accommodate 2-meter (6 feet) separation in classrooms; non-teaching staff provide support | Maximum class size 15 for Grades 1–4, 20 for Grades 5–7 | No maximum class size; classrooms are large enough to ensure 1–2 meter (3–6 feet) separation | No maximum class size; students in stable homerooms; subject-matter teachers move between classes |

| Classroom space/physical distancing | Group desks broken up; some use dividers | Physical distancing (2 meters) within classrooms; use of outdoor space, gyms, and secondary school classrooms | Physical distancing within classrooms; use of outdoor space encouraged | Group desks broken up in Grade 3 and up; 1–2 meter (3–6 feet) distance maintained | Group desks broken up; some use dividers |

| Arrival procedures | Designated routes to classes; multiple entrances | No family members past entry; staggered arrival/dismissal | No family members past entry; staggered arrival/dismissal | No family members past entry; parents report travel; staggered arrival/dismissal | No family members past entry |

| Mealtimes | Eat at desks or, if cafeteria used, seating is assigned in homeroom groups | Sit well apart while eating; no shared food | Eat at desks or, if cafeteria used, homeroom groups enter in shifts | Assigned seating in cafeteria with 1–2 meter (3–6 feet) spacing | Eat at desks; some use dividers |

| Recreation | Some schools have suspended physical education | Students play outside as much as possible; play limited to small groups within homeroom | Students sent outside as much as possible; play limited to small groups; outdoor space divided and use is staggered | Inter-school sports suspended; small-group play time staggered | Sports and physical education suspended |

| Transport | Using “customized school buses” with seats farther apart to limit proximity | School buses allowed; only one student per row | Private transportation encouraged; one student per row on buses | Still running buses and public transit | Still running buses and public transit, cleaning at least every 8 hours |

| Hygiene | Masks required, provided by the government; frequent handwashing | Frequent handwashing; posters and videos provided | Staff training on hygiene standards; frequent handwashing; posters and videos provided | Frequent handwashing; posters and videos provided | Masks required, provided by the government; windows and air vents left open |

| LearningPolicyInstitute.org @LPI_Learning facebook.com/LearningPolicyInstitute |

|

SOURCE: Reopening Schools in the Context of COVID-19: Health and Safety Guidelines from Other Countries by Hanna Melnick and Linda Darling-Hammond, with the assistance of Melanie Leung, Cathy Yun, Abby Schachner, Sara Plasencia, and Naomi Ondrasek is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International License.

Finally, ensuring that students and staff who are just beginning to experience symptoms do not come to school is one of the most important mitigation strategies that schools can adopt. To encourage this, the CDC recommends that districts and schools consider developing policies that encourage people to stay home when they are sick. For example, by eliminating perfect attendance awards for students or making sure that staff know there will not be negative repercussions if they need to stay home.

WHAT TO DO WHEN SOMEONE GETS SICK

As the committee notes, even with all of these mitigation strategies in place, it is likely that someone in the school community will contract COVID-19. The CDC provides guidelines on what to do in these circumstances. We highlight key steps here.

First, families and staff need clear guidance on symptoms of COVID-19, when to stay home, and the procedure for notifying school officials. As noted above, training for families and staff that includes these procedures will be needed. Clear guidance reminding families of the procedures should be sent to families and made available online. In addition, parents and students should have access to information, resources, and referral for COVID-19 testing sites prior to the beginning of the school year.

If someone develops symptoms at school, they need to quickly be isolated from the rest of the school population. This means that schools will need to create an isolation area and have designated staff, such as a school nurse, to monitor and care for the sick individual until they can be transported home or to a health care facility. Ideally, the isolation area will be vented to the outside to prevent droplets containing the virus to circulate in the rest of the building.

In accordance with state and local laws and regulations, school administrators will need to notify local health officials, school staff, and families immediately of any case of COVID-19 while maintaining confidentiality. They will also need to inform any individuals who have had close contact with a person diagnosed with COVID-19 to stay home and self-monitor for symptoms.

As noted earlier in the chapter, cleaning and disinfecting is especially important after someone who has tested positive for COVID-19 has been in the school. The areas used by the sick person will need to be closed off for at least 24 hours, if possible, before being cleaned and disinfected. School leaders will need to consult with public health officials about whether short-term closure of the building might be warranted (for example, if several students in a classroom, or several staff members test positive).

Students and staff who have been sick will not be able to return to the school until they have met the CDC criteria to discontinue home isola-

tion. Caregivers and staff will need to wait for formal notification from the school nurse or a physician that it is permissible for them to return to school.

Monitoring health of students and staff and caring for individuals who become sick will place a heavy burden on school nurses and other school health staff. In schools that currently employ part-time nurses or do not have a school nurse at all, staffing will need to be supplemented. Local health departments of hospital health systems may need to partner with schools to provide nurse triage services within the school district to handle parental health calls/inquiries and to act as a referral resource for faculty and staff to maintain the optimal health of children.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusion 5.1: The recommended list of mitigation strategies is long and complex. Many of the strategies require substantial reconfiguring of space, purchase of additional equipment, adjustments to staffing patterns, and upgrades to school buildings. The financial costs of consistently and fully implementing the strategies are high.

Conclusion 5.2: The extent to which mitigation strategies can be implemented and how will vary depending on the age of students, the physical constraints of the school building, and the resources available in the school or district. Implementing all of the recommended strategies will likely be challenging depending on the resources and the size and condition of the schools within a district. Districts that are already highly resourced and have well-maintained buildings will be more likely to be able to implement the full suite of strategies.

Conclusion 5.3: There is limited evidence about the relative effectiveness of the various mitigation strategies recommended for schools. This limited evidence base makes it difficult to provide clear guidance to schools about which strategies they may be able to relax or eliminate—given practical and cost constraints—without increasing the risk of viral transmission. Without input from outside experts, districts and schools are left on their own to make these difficult judgments.

Conclusion 5.4: Although cleaning and improving air quality and ventilation are important mitigation strategies, they are insufficient for limiting transmission of the virus enough to keep people from getting sick. Mask wearing, handwashing, and physical distancing are essential.

Conclusion 5.5: Even with all of the mitigation strategies in place and well implemented, it will be impossible to bring the risk of contracting the virus to zero. As long as the virus is present in communities, schools may be subject to transmission.