Appendix D

Integrating Community Vulnerabilities into the Assessment of Disaster-Related Morbidity and Mortality: Two Illustrative Case Studies

Authored by Emma Fine, National Academies staff, July 31, 2020

INTRODUCTION

The report of the Committee on Best Practices for Assessing Mortality and Significant Morbidity Following Large-Scale Disasters describes the lack of coordination across stakeholders; the absence of a standardized approach and terminology for estimating morbidity and mortality; and extreme variation in practices for collecting, recording, reporting, and using disaster-related mortality and morbidity data. The main chapters of the report address issues such as (1) describing the current architecture, methodologies, and information systems currently in use by state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) public health agencies; (2) identifying barriers to collecting, recording, and reporting mortality and morbidity data; and (3) reviewing analytical approaches and statistical methods for estimating mortality and morbidity at a population level. Early in the committee’s deliberation the committee acknowledged that the social determinants of health (SDOH) contribute in known and less well-defined ways to disaster-related mortality and morbidity; however, they were bound by the limitations of the report’s scope from conducting an in-depth review of these critical socio-environmental dimensions and how those relate to community vulnerabilities and mortality and morbidity assessment.

In response, this appendix paper was drafted to provide two high-level case studies summarizing the inextricable link between the SDOH and mortality and morbidity related to two disasters—Hurricane Katrina and the early months of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These case studies will also reflect on how these dimensions may relate to the collection, reporting, and recording of morbidity and mortality data.

Ultimately, efforts to explore the intersection of these issues inform our collective understanding of the factors underlying a community’s resilience and vulnerability to disasters.

The Value of Multidimensional Mortality and Morbidity Data

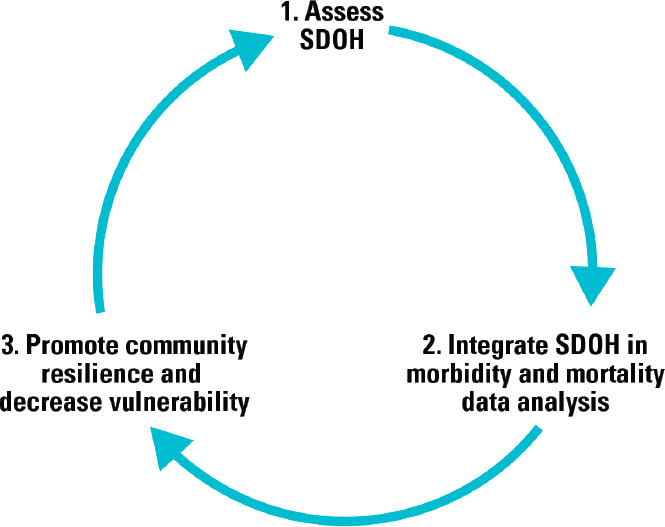

As described in the committee’s report, mortality and morbidity data represent a wide variety of uses and values. These data, if accurate and complete, can be used to identify at-risk populations, among other uses, and respond with appropriate actions to support recovery, mitigate root vulnerabilities, and prepare to prevent future harm, which represent great value to the field of disaster management. Critically, mortality and morbidity data alone represent just one category of data, and further contextualization of these data with other rich data points, such as race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, among others, provides for a multidimensional understanding of those same mortality and morbidity data. The integration of these data represent real opportunities to identify the underlying causal pathways and sub-population inequities existing at the intersection of the SDOH, disaster exposure, and disaster-related mortality and morbidity, which could in turn allow for the improved design and targeting of resources and programs to the sub-populations in greatest need. The contextualization of morbidity and mortality using SDOH data adds additional value and evidence to foster a stronger and more responsive disaster management enterprise that prioritizes community resilience (see Figure D-1).

While the SDOH operate at a subpopulation level, the contributory role of these factors on vulnerability should not be de-emphasized. For example, as Thomas-Henkel and Schulman (2017) write, “SDOH can account for up to 40% of individual health outcomes, particularly among low-income populations, [and] their providers are increasingly focused on strategies to address patients’ unmet social needs (e.g. food insecurity, housing, transportation, etc.).” Co-morbidities are one significant consequence of these unmet social needs (Valderas et al., 2009), which add distinct complexity to the assessment and use of disaster-related mortality and morbidity data. Certain socio-environmental factors—population density, exposure to pollution, outdoor manual labor—are known to increase biological susceptibility to disease, and those impacts seep into individual treatment and care of various medical conditions (McKibben, 2020). During and after a disaster, these influences are even more pronounced. Other SDOH, such as race and economic status, and other well-established determinants are known to be associated with persistent inequities in health and further indicate that the vulnerabilities as they relate to the SDOH are critical to understand alongside disaster-related mortality and morbidity data to provide a foundation of evidence for promoting community resilience.

NOTE: SDOH = social determinants of health.

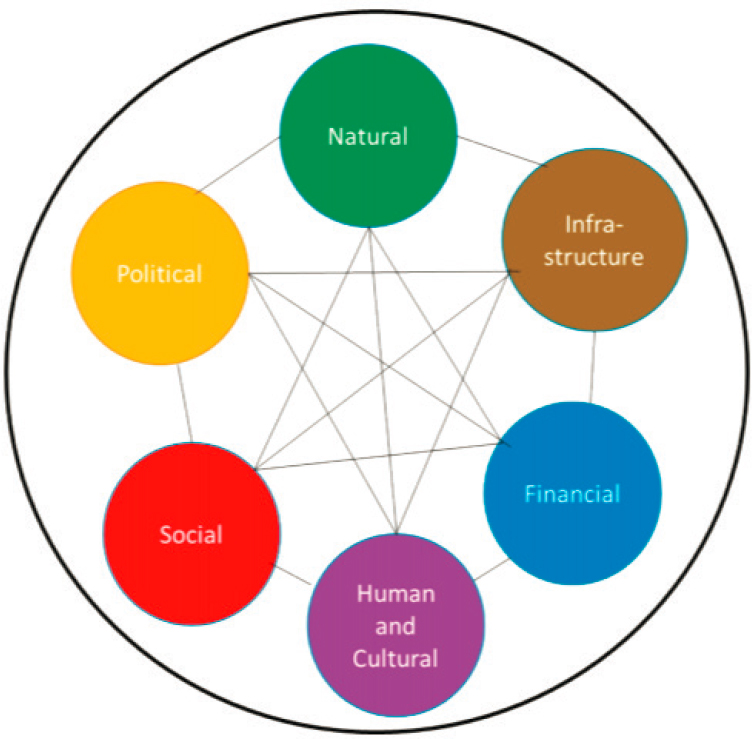

Because a body of literature already exists around how the SDOH relate to health disparities, and how disaster exposures further heighten these vulnerabilities and inequalities within marginalized populations (Healthy People 2020, 2017; NASEM, 2019), this appendix will not attempt to summarize this body of work. There are many different definitions for SDOH, as well as many various elements that comprise these determinants. For this appendix, the following definition of SDOH (see Box D-1) will be used, along with the following six key social capital elements (see Figure D-2).

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH AND DISASTER-RELATED MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY

Post-Hurricane Maria Puerto Rico: A Case Study

1. Natural (or environmental)

Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017, just 2 weeks after Hurricane Irma stuck the island and had already caused damage to roads, water supply, and access to medical care (Kishore et al., 2018). When Hurricane Maria hit the island, the storm was tracked as a “Category 4” and, over the past century, Maria was the strongest recorded

hurricane to hit Puerto Rico (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Widespread physical and infrastructural damage occurred as a result, the total number of deaths is still unknown, and the impact of the storm continues to have short- and long-term impacts on population health (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Kishore et al. (2018) write that damages from Hurricane Maria reached approximately $90 billion, ranking it as the third costliest hurricane in the United States since 1900 and resulted in the displacement of thousands of individuals and families from their homes (Kishore et al., 2018). The natural effects of the hurricane had large impacts on the population and migration of those in Puerto Rico. Data indicate that an estimated 114,000–213,000 (or between 2–4 percent) of the population left Puerto Rico in the year after the hurricane, often heading to places such as Florida or even as far away as Hawaii and Alaska (DeWaard et al., 2020). DeWaard et al. (2020) highlight that those who migrated out of Puerto Rico were commonly of school or working ages. This population drain from the island will have lasting impacts on the schooling, labor market, economy, and public service sectors and their trajectories within both Puerto Rico and the United States (DeWaard et al., 2020).

With regard to the environment, Hurricane Maria had strong impacts on the overall air quality and air pollution within Puerto Rico. Some of the most significant infrastructure damage caused by the hurricane was the destruction of the island’s electrical grid, which left many communities without power for months on end (ACS, 2018). In fact, 3 months after

SOURCE: NASEM, 2019.

Hurricane Maria struck, 50 percent of Puerto Rico still lacked electricity, and even those who did not lack access to electricity experienced ongoing power outages (ACS, 2018). As a consequence, many communities began to rely on backup generators that run on gasoline or diesel, leading to increased air pollution in communities where generators were widely used (ACS, 2018). During the period that the quality of the air was being monitored, 80 percent of those days showed sulfur dioxide levels that exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s air quality standards, and in many other places air quality could not be measured due to such significant damage (ACS, 2018). Population exposure to these higher levels of air pollution have lasting impacts on the respiratory health of those residing in Puerto Rico, especially in areas where the levels of pollution were extreme.

2. Built (infrastructure)

Even today, the exact number individuals who died as a result of Hurricane Maria remains unknown, illustrating a persistent shortcoming in disaster management and part of the impetus for the committee’s authoring of this report. The official death toll of Hurricane Maria remains 64. However, researchers from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, via survey data, argue that a more accurate estimate of all-cause mortality due to Hurricane Maria is 4,645 dead as a result of the storm (Kishore et al., 2018). This mortality estimate is more than 70 times the official estimate and represents a 62 percent increase in mortality compared to a similar time frame in 2016. However, even this is still likely to be an under-representation of the true impact of the disaster on human life (Kishore et al., 2018). Part of the higher mortality estimate exists due to the researchers’ integration of population displacement, loss of services, and excess deaths into the overall toll. For example, researchers found that on average, households impacted by the hurricane went 84 days without electricity, 68 days with no water, and just more than 40 days with no cellular service, with a disproportionate impact on those residing in more remote regions (Kishore et al., 2018). In terms of disruption to services, 31 percent of households surveyed reported an issue—14.4 percent of households were unable to access medications, 9.5 percent were unable to access electricity to operate respiratory equipment, 8.6 percent reported closed medical facilities, 6.1 percent were patients of absent doctors, and even 8.8 percent were unable to reach 911 (Kishore et al., 2018). After 3 weeks, nearly 94 percent of the island lacked power, 43 percent lacked potable water, and only 30 percent of the hospitals could provide services (Lybarger, 2018). All of these losses of services and interruption in care can lead to cases of morbidity and mortality that may not be captured in the overall estimate of reported mortality based on individual counts of deaths directly attributed to the disaster. The accuracy of the death count was also impacted by the rise of uncounted bodies (Dyer, 2017). BMJ reports that during the hurricane, hospitals and hospital morgues were overcrowded and that triaging and communication were major challenges. Even more so, morgues were so full that only those who had death certificates were added to the official mortality count, and morgues had the policy of not releasing bodies until the death certificate had been issued. This was compounded by the fact that some individuals responsible for issuing death certificates were themselves unaccounted for (Dyer, 2017), creating a cyclical problem.

Hurricanes are capable of extensive destruction of buildings and structures, including infrastructure that facilitates essential needs such as access to shelter, food, water, electricity, transportation, and communication, which all have impacts on a community’s public health (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Even prior to Hurricane Maria, the effects of SDOH were

clear for many individuals residing there. Nearly 44 percent of Puerto Rico’s residents live at or below the poverty level—compared to just under 13 percent in the United States—and the unemployment rate hovers around 10 percent (Michaud and Kates, 2017). In terms of overall health prior to the hurricane, nearly 34 percent of the population reported having fair or poor general health, 15.4 percent live with a disability, and the prevalence of diabetes was 50 percent higher when compared to that in the United States (Michaud and Kates, 2017). After the hurricane, the physical impacts on the built environment had significant impacts on the health of residents. Many were unable to access grocery stores or fresh food and had to rely on the nearly 1 million meals provided each day from emergency first responders even 1 month after the hurricane (Michaud and Kates, 2017). This lack of adequate food is tied to other health conditions and can result in malnutrition, which can both cause and exacerbate other co-morbidities (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Puerto Rico also saw an increase in conditions related to the consumption of unclean water as some communities were left without access to safe water and had to result to natural freshwater sources, subject to human and environmental contamination (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Hospitals also suffered infrastructural damage to the extent that only three of the island’s major hospitals were functioning 3 days after the hurricane. One month later, 40 percent of tracked hospitals were still running on backup generators. Running on generators was also a significant problem for those relying on dialysis centers to treat the high burden of diabetes in Puerto Rico (Michaud and Kates, 2017). These examples illustrate how the infrastructure of Puerto Rico was significantly damaged by the 2017 hurricane, and how certain populations, such as those with diabetes, were at an increased risk for mortality or morbidity related to the hurricane as a result of the storm’s impacts to the built environment.

3. Financial (economic)

Puerto Rico faced public health challenges both before and after the arrival of Hurricane Maria. The financial status of many hospitals, after suffering severe structural damage, remained an issue at least through 2018, when Chowdhury et al. (2019) conducted interviews in Puerto Rico. Hospital employees in 2018 reported that structural damage from the hurricane damaged a cardiac catheterization lab and a cancer institute and described how many hospitals experienced flooding that damaged x-ray and other imaging technology. Chowdhury et al. (2019, p. 1727) writes

Financially, the hospital was already short of funds for needed improvements before the hurricanes. After the hurricanes, the hospital had accrued hundreds of millions of dollars in damages, and substantial questions re-

main about the best way to move forward, weighing the relative benefits of rebuilding, replacing, or accepting the loss of facilities.

Financial debt has led to the loss of treatment centers for various diseases, likely impacting the number of patients who can be treated, which exacerbated risks for mortality and morbidity.

However, these financial strains did not just impact large buildings and structures, but also the communities and individuals residing within Puerto Rico. Rodriguez-Diaz (2018) explains that the under-resourced communities experienced exacerbated public health effects due to inadequate health systems and lack of sufficient humanitarian disaster relief, which led to “outbreaks of infectious diseases, limited access to clean water, and malnutrition, among other problems.” Additionally, the slow and limited federal response to the hurricane disaster highlighted the impact of poverty on many communities. Indeed, Rodriguez-Diaz (2018, p. 31) indicates that “poverty has the largest impact in terms of health inequities after the hurricane and magnif[ies] the impact of social determinants of Puerto Ricans’ health (e.g., housing, health care services, access to clear water and sanitation.” The SDOH, such as financial capital, have clear implications for the ability of a locality to recover from adversity and also for its most financially vulnerable populations.

4. Social/Psychosocial

Hurricanes not only damage the natural and built environments but they can also negatively impact mental health. Hurricanes can lead to an increased risk for conditions such as anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Scaramutti et al., 2018). Within 2 months of the hurricane’s arrival, the demand for mental health services increased sharply and individuals were reporting anxiety and depression more frequently, even among those who had never experienced these previously (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Chowdury et al. (2019, p. 1728) write of other alarming events such as “perceived amplified behavioral and mental health issues on the island such as thefts resulting in gunshot wounds, domestic violence, alcohol use disorders, and depression.” These mental health impacts are not thought to exist only in the short term. Kaiser Family Foundation reported that, in fact, adverse mental health conditions may even increase over the following months and years after the hurricane. For example, those affected similarly by Hurricane Katrina saw elevated rates of mental illness that were sustained for more than 1 year after the event (Michaud and Kates, 2017). Hurricane Maria undoubtedly had impacts on the mental health of the residents of Puerto Rico (Lybarger, 2018), and the lasting structural damage alongside increased demand for mental health services likely compounded the impact this SDOH capital on morbidity and mortality.

5. Human and Cultural

While the hurricane had impacts on the physical environment and health of Puerto Rico’s citizens, it also created profound damage on some of society’s most vulnerable—children. A study, which was also the largest sample ever of Hispanic youth impacted by disaster, indicated just some of these consequences on children. Nearly 50 percent of children’s family homes were damaged and nearly 84 percent of children witnessed damaged homes; 24 percent of children helped rescue others; 25.5 percent of children were forced to evacuate; 32 percent experienced shortages of food and water; and nearly 17 percent still did not have electricity between 5 to 9 months after the hurricane. Additionally, nearly 58 percent had a family member or friend leave Puerto Rico (Orengo-Aguayo et al., 2019). The cultural and social implications of what these children faced may have long-term consequences, and stress the need for disaster management to include the SDOH in policy and practice.

6. Political (institutional or governance)

Puerto Rico provides appropriations to the Federal Emergency Management Agency annually in order to utilize their disaster relief management efforts; however, the arrival and subsequent damage that Hurricane Maria caused exposed colonial laws that limit Puerto Rico’s abilities to recover from natural disasters (Rodriguez-Diaz, 2018). Two of these significant laws are the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (commonly known as the Jones Act) and the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) (Rodriguez-Diaz, 2018). The Jones Act ensures that the “maritime waters and ports of Puerto Rico are controlled by U.S. agencies,” which, downstream, means that “under this kind of control, the cost of consumer goods arriving to Puerto Rico can be higher than in the Continental U.S. … and [it] restrains the ability of non-U.S. vessels and crews to engage in commercial trade with Puerto Rico” (Rodriguez-Diaz, 2018, p. 30), which ultimately serves to restrict the economic independence of this territory. Additionally, PROMESA “limits the Puerto Rican government’s disaster response by restricting the amount of resources the state can mobilize locally in attending to the crises brought by the 2017 hurricane season” (Rodriguez-Diaz, 2018, p. 30). The natural disaster and the burden of political and economic restraints resulting from these two laws (Rodriguez-Diaz, 2018) made managing post-disaster response and recovery extremely challenging. The prolonged delay in receiving the materials and supplies needed may have further impacted morbidity and mortality caused by this natural disaster.

Early Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study

Substantial evidence exists demonstrating the impact of social determinants on the vulnerabilities of certain communities and populations to the adverse outcomes of disasters. For example, “social determinants exert a powerful influence on different elements of risk, principally vulnerability, exposure and capacity and thus, on people’s health” (Nomura et al., 2016). Vincent Lafronza and Natalie Burke write that

social conditions are major determinants of health” with “social forces acting at a collective level shaping individual biology, individual risk behaviors, environmental exposures, and access to resources that promote health … and while public health programs alone cannot ameliorate the social forces that are associated with poor health outcomes, developing a better understanding of the social determinants of health is critical to reducing health disparities. (Lafronza and Burke, 2007, p. 12)

Using the SDOH definition, the six elements that comprise it (see Box D-1), and the global pandemic of COVID-19, examples will be provided to show exactly how influential the SDOH are in the outcomes of morbidity and mortality during a disaster, specifically in reference to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a virus that typically manifests in respiratory illness along with other symptoms such as fever, shortness of breath, and unexplained loss of taste or smell (Sauer, 2020). In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020) as the virus continued to spread across every continent except Antarctica (Sikorska, 2020). As of July 2020, the United States has seen more than 135,991 deaths from COVID-19 with more than 3.4 million total cases (CDC, 2020). Unprecedented measures such as school, work, and restaurant closures; legal requirements to wear face masks; and social distancing policies have been implemented worldwide in efforts to reduce the spread of this potentially fatal virus. However, through our understanding of the SDOH, the coronavirus and its implications for morbidity and mortality do not impact all individuals or communities equally.

1. Natural (or environmental)

One of the key ways coronavirus transmits is through air droplets—meaning proximity to and density of people, especially when indoors—is extremely important to transmission of the infection. A study of overcrowding in housing found that, for those that had one or more persons per room,

only 1 percent of non-Hispanic whites fell into this category compared to 12 percent of Hispanics. Even when looking at overcrowding in housing based on citizenship, only 1 percent of those born in the United States had one or more persons per room while 15 percent of foreign-born (not a U.S. citizen) individuals had one or more persons per room. Therefore, natural or environmental factors such as overcrowding in housing can be, at times, directly related to social factors such as race or nationality, which, in the case of COVID-19, can have direct implications for infection and transmission, and ultimately mortality. If Hispanic populations, compared to non-Hispanic whites, are more likely to experience overcrowding in housing, they are also more likely to be at greater risk for COVID-19, which is more easily transmitted among individuals in dense indoor environments (Benfer and Wiley, 2020).

Redlining, defined as “a discriminatory practice by which banks, insurance companies, etc., refuse or limit loans, mortgages, insurance, etc., within specific geographic areas, especially inner-city neighborhoods” (Dictionary.com, 2020), commonly practiced in the 1930s, is not a vestige of the past. A study conducted by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition in 2018 indicated that a majority of the homes that were redlined, or marked as “hazardous” by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation during the period from 1935 to 1939, are today “much more likely than other areas to comprise lower-income, minority residents” (Jan, 2018). These dated policies have stagnated and stunted economic growth where three out of four redlined neighborhoods still struggle economically 80 years later (Jan, 2018; Mitchell and Franco, 2018). This result of concentrated poverty ultimately puts low-income communities of color in less safe areas geographically and they are often at higher risks for co-morbidities. According to research by the Tulane University School of Public Health & Tropical Medicine, minority groups are at highest risk for COVID-19 due to their higher rates of co-morbidities such as heart disease and obesity, they have higher rates of multigenerational household units, and compared to their White counterparts they face a greater difficulty in access to the necessary testing. These minority communities also experience barriers to health and economic opportunity and, often due to their employment, are unable to comply with social distancing guidelines meant to protect them from COVID-19 itself (Patel et al., 2020; Raifman and Raifman, 2020).

The natural environment, such as housing or zip code, can greatly influence or sway the likelihood that certain individuals or populations will be at increased risk for contracting and transmitting COVID-19, which directly impacts morbidity and mortality and clearly shows how these rates are impacted by the SDOH.

2. Built (infrastructure)

A consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the alteration of work environments—many individuals found themselves working full time at home while other workers, often those serving low-wage jobs such as restaurant workers or grocery store cashiers, were unable to remain protected at home as their work became deemed “essential” (Burkholder et al., 2020). These essential workers were forced to either show up to their workplaces—increasing their own exposure to COVID-19—or face potentially losing their jobs. Amid this disaster, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, part of which served to make it easier for workers to receive paid sick leave if they contract COVID-19 or are responsible for caring for out-of-school children (Khazan, 2020). This act established a 2-week period of paid sick leave for quarantined or symptomatic individuals as well as 12 weeks of paid leave at a rate of two-thirds of their salary if they are taking care of a child (Khazan, 2020). However, many employees are not eligible to receive these protections—this law exempts employers with more than 500 employees, and those with fewer than 50 employees are eligible to file for an exemption (e.g., local grocery stores, restaurants, or Amazon employees). The Center for American Progress found that “only 47% of private-sector workers will have guaranteed access to coronavirus-related sick leave” (Khazan, 2020). Policies such as these serve to reinforce the difficult decision many essential employees face to either stay home when sick or lose their job. The Center for Economic and Policy Research found that “the United States is the only 1 of 22 rich countries that fails to guarantee workers some form of paid sick leave” and that the United States is also “1 of only 3 countries that does not provide paid sick days for a worker missing 5 days of work due to the flu” (CEPR, 2020). Infrastructural challenges such as relying on essential business coupled with the lack of protections for these essential workers and low-wage nature of these jobs means that low-wage workers are more exposed and more susceptible to contracting COVID-19. Additionally, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Flexibilities and Work Schedules Summary shows that 37 percent of Asians, 30 percent of non-Hispanic or non-Latinos, 29.9 percent of Whites, 19.7 percent of Blacks, and just 16.2 percent of Hispanic or Latino populations are eligible to work from home (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). These infrastructural inequities ensure that the risk of COVID-19 exposure and infection does not impact all persons equally and illustrates the reality that minority populations and low-wage workers bear the brunt of the potential morbidity and mortality.

Beyond employee paid sick leave, other built or infrastructural elements also impact morbidity and mortality. According to Tulane University, minority groups face greater difficulty in accessing COVID-19 testing when compared to their White counterparts (Lieberman-Cribbin et al., 2020).

Many of the first testing sites established were drive-through only, excluding access to testing for those who did not have vehicles (Griffith et al., 2017). Black, indigenous, and other populations of people of color are also less likely to be insured compared to their White counterparts. Ellis (2020) argues that “structural inequalities have kept black Americans significantly poorer than their white counterparts, and economic disparity creates health disparities, especially during a pandemic,” which is strongly supported by research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which cites discrimination (including racism) as having an impact on overall well-being and health (CDC, 2020c). The built or infrastructural elements of SDOH have clear and lasting implications for disease prevalence and incidence and thus morbidity and mortality.

3. Financial (economic)

An important indicator of health, as well as an SDOH, is the level of wealth of an individual or community. COVID-19 presents a key example of how rich individuals and families were able to flee New York City, a virus hotspot, to safer areas throughout the United States. Data show that between March 1 and May 1, 2020, about 5 percent of New York City residents (approximately 420,000 people) left the city. Extremely affluent neighborhoods, such as the Upper East Side or SoHo, however, saw their residential populations decrease by 40 percent or more, with the overall trend indicating that “the higher-earning a neighborhood is, the more likely it is to have emptied out,” where out of all of the neighborhoods to see population dips, the highest-earning ones emptied out first (Quealy, 2020). The populations of the neighborhoods that did empty are mostly White, have lower poverty rates, and are more likely to be able to walk or bike to work or work from home; and more than half of the residents of these neighborhoods have incomes that exceed $100,000, with one in three earning more than $200,000 (Quealy, 2020). This example exposes how the SDOH, particularly financial wealth, can provide an opportunity for escaping a disaster or a sentencing to experience it personally. As the wealthy flee the viral hot spot, they are able to reduce their likelihood of infection and transmission—their financial status serving protections that are not afforded to others. This ultimately creates a situation where those with less financial security are simultaneously forced to face the brunt of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality—“the lower a person’s socioeconomic status, the more limited their resources and ability to access essential goods and services, and the greater their chance of suffering from chronic disease, including conditions like heart disease, lung disease, and diabetes that may increase the mortality risk of COVID-19” (Benfer and Wiley, 2020).

4. Social/Psychosocial

A recent survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that nearly half of all Americans (45 percent) indicate that, due to stress and worry related to COVID-19, their mental health has been negatively impacted (Panchal et al., 2020). Compounding the anxiety individuals feel while facing the pandemic, policies such as sheltering in place can exacerbate feelings of negative mental health or stress. The same study showed that 47 percent of individuals sheltering in place reported negative mental health effects compared to 37 percent of those not sheltering in place (Panchal et al., 2020). Another consequence of COVID-19, job loss, may at first appear to have exclusively economic implications but this has psychological impacts as well. Recent polls show that more than half of those who have lost their job or experienced reduced income report higher rates of major mental health issues than high-income, employed individuals. Additionally, job loss is “associated with increased depression, anxiety, distress, and low self-esteem and may lead to higher rates of substance use disorder and suicide” (Panchal et al., 2020). By gender, 24 percent of females compared to 15 percent of males feel that the coronavirus has had a negative impact on their mental health (Kirzinger et al., 2020). By race, 17 percent of Whites compared to 24 percent of Blacks and Hispanics feel that their mental health has been majorly impacted by the pandemic (Kirzinger et al., 2020). These rates of increased mental health distress among certain populations have key implications for morbidity and mortality outcomes, showing once again the role that the SDOH have in managing disaster-related morbidity and mortality.

Certain populations also face increased susceptibility to mental health issues amplified by COVID-19. Older adults are not only more likely to develop serious illness if they contract COVID-19 but they are also at high risk of poor mental health due to loneliness and bereavement. According to research by JAMA, adolescent populations are also at risk for either worsening existing mental health or creating new mental health issues (Golberstein et al., 2020). Nearly 55 million students ranging from kindergarten to high school seniors were impacted by COVID-19-related school closures. This is not only a consequence for their learning but schools are often major sources of nutrition as well as providers of health care and mental health services—in fact, from 2012 to 2015, 35 percent of students received mental health services exclusively from school (Golberstein et al., 2020). In the absence of resources such as community for elders or mental health services for adolescent populations, COVID-19 has implications on mental health, one of the key pillars of the SDOH. Mental health, exacerbated by COVID-19, clearly has implications for morbidity and mortality for more than half of Americans, specifically populations more vulnerable to psychological issues and stress.

5. Human and Cultural

The nature of the spread of COVID-19, originating in late 2019 in Wuhan, China, created stigma about the coronavirus to certain subsets of the population such as those of Asian descent, individuals who had traveled, and even first responders and health care workers (CDC, 2020b). Additionally, policies implemented to diminish the spread of the virus may actually further stigmatize already stigmatized populations who cannot comply with the policies (Logie and Turan, 2020). For example, COVID-19-related policies included travel bans, social distancing, and quarantines. These movement-related guidelines further stigmatize already stigmatized populations such as homeless persons, racial minorities, migrants, and refugees (Logie and Turan, 2020). Importantly, this has strong implications for morbidity and mortality. Individuals or populations facing stigmatization may face social avoidance or rejection, refusal of service for health care, education, housing, or employment, and may also be subject to or targets of physical violence (CDC, 2020b). A joint statement released by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the United Nations Children’s Fund, and WHO warns that stigmatization can actually enhance the spread of the virus, not hamper it, and it can lead to infected individuals hiding their illness, prevent people from seeking care right away, and can even discourage the exhibition and practice of healthy behaviors (IFRC et al., 2020).

Alongside stigma, race, another SDOH, plays a significant role in COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality. According to patient analysis of a health care system in Northern California, Black patients were hospitalized at nearly three times the rate of White and Hispanic patients when seeking medical care for COVID-19 (Azar et al., 2020). This study also found that Black patients may experience limited access to care or delayed seeking help until the disease had clinically advanced and were also less likely to have been tested for the virus prior to seeking treatment when compared to White, Hispanic, or Asian patients (Azar et al., 2020; Rabin, 2020). An especially important finding showed that the disparity exists even after “differences in age, sex, income, and the prevalence of chronic health problems that exacerbate COVID-19, such as hypertension and Type 2 diabetes” (Rabin, 2020) were taken into account, indicating that race itself is a large factor when evaluating rates of morbidity and mortality.

6. Political (institutional or governance)

As COVID-19 began to spread across the United States, the implementation of policies such as stay-at-home orders were not issued federally, but at the state level. This state-by-state nature allowed governors and mayors to decide for their constituents how, when, and to what degree they would

establish, maintain, and enforce these policies as well as when they would allow their states to begin to reopen. By allowing states to autonomously operate, differences in shutdown and reopening timelines can be seen across all 50 states. For instance, Alabama saw their stay-at-home order expire on April 30, 2020, with many businesses able to open that day and all business allowed to open by May 22, 2020. Arkansas, on the other hand, did not have a statewide stay-at-home order in place at any time, with a phased reopening beginning May 6, 2020. New Hampshire’s stay-at-home order was initiated March 27, 2020, and expired June 15, 2020, with some businesses opening May 11, 2020. California, one of the earliest states to enact stay-at-home orders on March 19, 2020, has still not issued a formal closure of that policy but has created their own phased reopening starting May 12, 2020 (Lee et al., 2020). These variable reopening times staggering through April, May, and June 2020—along with staggered start times, if implemented at all, for the initial stay-at-home orders—means that the United States is seeing inconsistent patterns in cases and overall spread. The likelihood of increased or decreased exposure to COVID-19 could ultimately be left up to state leaders and significantly impact the number of COVID-19 cases in a first and potential second wave. The politics of one’s zip code, a clear SDOH, in this case, can be clearly tied to the incidence and prevalence of COVID-19, which directly links to its related morbidity and mortality.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH AND MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY ASSESSMENT: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE

As highlighted throughout the report, the absence of the systematic collection of disaster-related morbidity and mortality data, variation in SLTT data collection and recording systems, and the wide range of stakeholders involved only complicate the assessment and use of data to the benefit of the disaster management enterprise. These data are crucial for guiding response and recovery priorities, ensuring a common operating picture and real-time situational awareness across stakeholders, and protecting vulnerable populations and settings at heightened risk. While mortality and morbidity data hold immense potential value, the lack of incorporation of the SDOH into the collection and assessment of these data limits the degree to which these data can inform changes in policy, practice, and behavior.

The incorporation of SDOH data into morbidity and mortality assessment for the purpose of informing the disaster management enterprise will require improvements in data collection, recording, reporting, and use if these data are to be used in collaboration to identify groups most at risk and can help target public health efforts more successfully. For example,

despite widespread public perception that the federal government and the private sector collect vast amounts of data, the availability of racial and ethnic data in the health care system itself is quite limited. A variety of government sources include data on race and ethnicity, but the utility of these data is constrained by ongoing problems with reliability, completeness, and lack of comparability across data sources. (NRC, 2004, p. 203)

Many barriers persist for gathering the data related to the SDOH, which transcend law, policy, regulation, and ethics such as patient privacy, confidentiality, civil rights laws, and the administrative burden imposed on various organizations and entities (NRC, 2004). Despite these barriers, the integration of SDOH into the measures of morbidity and mortality data will be critical to mitigate the impact of disasters, especially on those living in disaster-prone areas, and to set priorities for targeting health and other disaster management resources. For example, there is increasing awareness that policies and resources are needed to address mental health, trauma, and chronic illness as the primary morbidities related to disasters. The National Research Council (2001, p. 24) writes, “measuring only mortality during an emergency says nothing about sequelae of complex emergency that may have profound effects on the population.” Therefore, SDOH data hold intrinsic value, which can be tapped to more accurately interpret mortality and morbidity data following disasters and target the root causes of community vulnerabilities to disasters—a value that will likely expand as certain disasters grow in frequency and severity.

REFERENCES

ACS (American Chemical Society). 2018. Monitoring air pollution after Hurricane Maria. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/pressroom/presspacs/2018/acs-presspac-october-31-2018/monitoring-air-pollution-after-hurricane-maria.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

Azar, K., Z. Shen, R. Romanelli, S. Lockhart, K. Smits, S. Robinson, S. Brown, and A. Pressman. 2020. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Affairs 39(7):1253–1262. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598.

Benfer, E., and L. Wiley. 2020. Health justice strategies to combat COVID-19: Protecting vulnerable communities during a pandemic. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200319.757883/full (accessed October 1, 2020).

Burkholder, S., S. Eldred, K. Harrison Belz, N. Keppler, M. Kreidler, M. Majchrowicz, B. Martin, S. Wang, J. Eilperin, D. Santamariña, and R. Fischer-Baum. 2020. What counts as an essential business in 10 U.S. cities. The Washington Post, March 25. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/national/coronavirus-esssential-businesses (accessed September 1, 2020).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2020a. Coronavirus disease 2019: Cases & deaths in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/us-casesdeaths.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

CDC. 2020b. Coronavirus disease 2019: Reducing stigma. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/reducing-stigma.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

CDC. 2020c. Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fneedextra-precautions%2Fracial-ethnic-minorities.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

CEPR (Center for Economic and Policy Research). 2020. United States lags world in paid sick days for workers and families. https://cepr.net/documents/publications/psd-summary.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

Chowdhury, M., A. J. Fiore, S. A. Cohen, C. Wheatley, B. Wheatley, M. Puthucode Balakrishnan, M. Chami, L. Scieszka, M. Drabin, K. A. Roberts, A. C. Toben, J. A. Tyndall, L. M. Grattan, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 2019. Health impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on St Thomas and St John, US Virgin Islands. American Journal of Public Health 109(12):1725–1731. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305310 (accessed September 1, 2020).

Cucinotta, D., and M. Vanelli. 2020. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomedica 91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397.

DeWaard, J., J. Johnson, and S. Whitaker. 2020. Out-migration and return migration to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria: Evidence from the consumer credit panel. Population and Environment 42:28–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-020-00339-5.

Dictionary.com. 2020. Redlining. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/redlining (accessed September 1, 2020).

Dyer, O. 2017. Puerto Rico’s morgues full of uncounted bodies as hurricane death toll continues to rise. BMJ 359:j4648. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4648.

Ellis, E. G. 2020. COVID-19 is killing black people unequally—don’t be surprised. Wired Magazine. https://www.wired.com/story/covid-19-coronavirus-racial-disparities (accessed September 1, 2020).

Golberstein, E., H. Wen, and B. Miller. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics 174(9):819–820. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456.

Griffith, K., L. Evans, and J. Bor. 2017. The Affordable Care Act reduced socioeconomic disparities in health care access. Health Affairs 36(8):1503–1510. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0083.

Healthy People 2020. 2017. Chapter 39: Social determinants of health (SDOH). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hpdata2020/HP2020MCR-C39-SDOH.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and WHO (World Health Organization). 2020. Social stigma associated with COVID-19. https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/Social%20stigma%20associated%20with%20the%20coronavirus%20disease%202019%20%28COVID-19%29.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

Jan, T. 2018. Redlining was banned 50 years ago. It’s still hurting minorities today. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/03/28/redlining-was-banned-50-years-ago-its-still-hurting-minorities-today (accessed September 1, 2020).

Kirzinger, A., A. Kearney, L. Hamel, and M. Brodie. 2020. KFF health tracking poll—early April 2020: The impact of coronavirus on life in America. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-health-tracking-poll-early-april-2020 (accessed September 1, 2020).

Kishore, N., D. Marqués, A. Mahmud, M. V. Kiang, I. Rodriguez, A. Fuller, P. Ebner, C. Sorensen, F. Racy, J. Lemery, L. Maas, J. Leaning, R. A. Irizarry, S. Balsari, and C. O. Buckee. 2018. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. New England Journal of Medicine 379:162–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972.

Lafronza, V., and N. Burke. 2007. Katrina and social determinants of health: Toward a comprehensive community emergency preparedness approach. http://cretscmhd.psych.ucla.edu/nola/volunteer/FoundationReports/CHA_KatrinaSocialDet.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

Lee, J., S. Mervosh, Y. Avila, B. Harvey, and A. Leeds Matthews. 2020. See how all 50 states are reopening (and closing again). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

Lieberman-Cribbin, W., S. Tuminello, R. M. Flores, and E. Taioli. 2020. Disparities in COVID-19 testing and positivity in New York City. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 59(3):326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005.

Logie, C., and J. Turan. 2020. How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS and Behavior 24:2003–2006. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02856-8.

Lybarger, J. 2018. Mental health in Puerto Rico. American Psychological Association 49(5):20. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/05/puerto-rico (accessed September 1, 2020).

McKibben, B. 2020. Racism, police violence, and the climate are not separate issues. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-a-warming-planet/racism-police-violence-and-the-climate-are-not-separate-issues (accessed September 1, 2020).

Michaud, J., and J. Kates. 2017. Public health in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/other/issue-brief/public-health-in-puerto-rico-after-hurricane-maria (accessed September 1, 2020).

Mitchell, B., and J. Franco. 2018. HOLC “Redlining” maps: The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/02/NCRC-Research-HOLC-10.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Building and measuring community resilience: Actions for communities and the Gulf Research Program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25383.

Nomura, S., A. Parsons, M. Hirabayashi, R. Kinoshita, Y. Liao, and S. Hodgson. 2016. Social determinants of mid- to long-term disaster impacts on health: A systematic review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 16:53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.01.013.

NRC (National Research Council). 2001. Forced migration and mortality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10086.

NRC. 2004. Eliminating health disparities: Measurement and data needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10979.

Orengo-Aguayo, R., R. Stewart, M. de Arellano, J. Suarez-Kindy, and J. Young. 2019. Disaster exposure and mental health among Puerto Rican youths after Hurricane Maria. JAMA Network Open 2(4):e192619. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2619.

Panchal, N., R. Kamal, K. Orgera, C. Cox, R. Garfield, L. Hamel, C. Munana, and P. Chidambaram. 2020. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use (accessed September 1, 2020).

Patel, J. A., F. B. H. Nielsen, A. A. Badiani, S. Assi, V. A. Unadkat, B. Patel, R. Ravindrane, and H. Wardle. 2020. Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: The forgotten vulnerable. Public Health 183:110–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006.

Quealy, K. 2020. The richest neighborhoods emptied out most as coronavirus hit New York City. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/15/upshot/who-left-new-york-coronavirus.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

Rabin, R. 2020. Black coronavirus patients land in hospitals more often, study finds. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/health/coronavirus-black-patients.html (accessed September 1, 2020).

Raifman, M. A., and J. R. Raifman. 2020. Disparities in the population at risk of severe illness from COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and income. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 59(1):137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.003.

Rodriguez-Diaz, C. 2018. Maria in Puerto Rico: Natural disaster in a colonial archipelago. American Journal of Public Health 108(1):30–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304198.

Sauer, L. 2020. What is coronavirus? Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus (accessed September 1, 2020).

Scaramutti, C., C. Salas-Wright, S. Vos, and J. Schwartz. 2019. The mental health impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 13(1):24–27. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.151.

Sikorska, K. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 as a challenge for maritime medicine. International Maritime Health 71(1):4. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2020.0002.

Thomas-Henkel, C., and M. Schulman. 2017. Screening for social determinants of health in populations with complex needs: Implementation considerations. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. https://www.chcs.org/media/SDOH-Complex-Care-ScreeningBrief-102617.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019. Job flexibilities and work schedules summary. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/flex2.nr0.htm (accessed September 1, 2020).

Valderas, J., B. Starfield, B. Sibbald, C. Salisbury, and M. Roland. 2009. Defining comorbidity: Implications for understanding health and health services. Annals of Family Medicine 7(4):357–363. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2713155/pdf/0060357.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2020. Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en (accessed September 1, 2020).