4

Interventions to Reduce Food Waste at the Consumer Level

In the past decade, policy makers, researchers, nonprofit organizations, and industry leaders have focused increasing attention on efforts to reduce the wasting of food at the consumer level (see Chapter 2), but research on the effectiveness of interventions1 to reduce such waste is still relatively new. The committee searched the relevant literature for insights that can support the development of effective interventions to reduce food waste. As with the research on drivers of consumer behavior (see Chapter 3), we looked first at the literature from the six related domains (energy conservation, water conservation, waste prevention/management, recycling, diet change, and weight management), with a focus on ideas that may allow food waste researchers to leapfrog forward on the basis of findings that may transfer across domains. We then turned to the available studies that have assessed the efficacy of interventions to reduce food waste at the consumer level. We developed a process for filtering the available research to identify those ideas supported by research with the strongest evidentiary methodological rigor, as well as the impacts that have been documented and the populations and contexts in which the interventions were assessed. We then considered the alignment of the ideas that emerged from this body of work with the motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) framework and summarized key findings about the primary types of interventions that have been studied (details about selected studies are in Appendix D). This chapter presents the results of that analysis, as well as a discussion of the

___________________

1 An intervention is defined as a combination of program elements designed to produce behavior changes among individuals or an entire population (Michie et al., 2011).

limitations of the existing literature and the themes that emerged from these two bodies of work.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM RELATED DOMAINS

Work from the six related domains offers insights about ways to modify behavior that may be useful for understanding and contextualizing the literature on food waste interventions. Although these fields differ in their goals and methods and use different terminology (see Chapter 1), common themes emerged across the literatures. The committee explored systematic reviews, narrative reviews, and meta-analyses to identify findings that would potentially be useful in the context of reducing consumer food waste. A few selected studies with empirical data were also reviewed. (The findings from this research are described more fully in Appendix E.) We identified four broad lessons about interventions to change behavior, which, not surprisingly, overlap with the lessons learned from these six fields about drivers of consumer behavior.

Multifaceted interventions that take advantage of more than one intervention strategy may be more effective than a single strategy alone. While it can be difficult to measure, depict, and disaggregate which strategies influence which behaviors, there is reason to believe that, in general, a combination of strategies is more likely than a single strategy to result in ample and sustained change in complex behaviors (e.g., Cox et al., 2010; Koop et al., 2019; Marteau, 2017; Sharp et al., 2010; Thomson and Ravia, 2011; Varotto and Spagnolli, 2017). A related point is highlighted by a meta-analysis from the weight management domain, which suggests that targeting multiple behaviors (in this case, dietary behaviors and physical activity) may be more effective than targeting single behaviors at stimulating weight loss (Sweet and Fortier, 2010). Similarly, a meta-analysis of behavior change interventions related to weight loss suggests that addressing motivation (e.g., with a communication style that addresses the motivation) along with ability (e.g., offering skills for “how to”) can be effective in initiating and sustaining behavior change (Samdal et al., 2017). Further, a systematic review of studies of solid waste management efforts shows that, although they can help increase societal awareness, public education interventions alone (without addressing beliefs, motivations, or attitudes) are insufficient to change behavior (Ma and Hipel, 2016). An important exception is identified in a recent review by Nisa and colleagues (2019) showing that for certain structured settings, simple alterations to choice architecture (i.e., nudges) can yield efficacy and effectiveness.

Contextual factors can play a key role in supporting or undermining behavior change. Research on efforts to reduce waste through recycling suggests that characteristics of the context or environment in which a behavior is occurring may have as great an influence on that behavior as individual-level factors, and that that there are many barriers to change, particularly outside the household context. External factors may either support or override individuals’ desire to waste less, or undermine efforts they make to consume or waste less (Cox et al., 2010). Two studies illustrate this point. The first, a small-scale study, examines waste reduction behaviors at home, at work, and on vacation, and shows that in the latter two contexts, people are less motivated to act proenvironmentally and perceive that they have less control over barriers to such behaviors than they do at home (Whitmarsh et al., 2018). The authors conclude that having a proenvironmental identity as a motivator is not a significant predictor of cross-contextual consistency. The second study, a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological strategies for promoting household recycling, shows that environmental alterations that minimize the effort required (such as adding bins for waste sorting) are the second most effective strategy in changing behavior, after social modeling2 (Varotto and Spagnolli, 2017).

Effective interventions may stimulate different types of cognitive processing. Meta-analyses show that effective interventions appeal to one or more of three types of cognitive processing: reflective, semireflective, or automatic.3 Generally, interventions designed to appeal to reflective processing (e.g., those to increase a person’s knowledge about reasons for performing a behavior or to appeal to their self-efficacy) have been found to be insufficient to promote behavior change (Koop et al., 2019; Sharp et al., 2010; Thomson and Ravia, 2011; Varotto and Spagnolli, 2017). However, it has also been found, in the context of household recycling, that if people are already motivated to act, encouraging them to reflect on how to act may promote a desired behavior (Varotto and Spagnolli, 2017).

___________________

2 The authors define social modeling interventions as those that include any kind of passing of information via demonstration or discussion in which the initiators indicate that they personally engage in the targeted behavior.

3 “Reflective processing” refers to conscious processing of information where attitudes are formed in light of rational arguments, relevant experiences, and knowledge. Tactics for interventions that appeal to this type of processing include knowledge transfer designed to increase self-efficacy. “Semireflective processing” refers to the formation of attitudes through rules of thumb and simple heuristics or cues. Tactics for interventions that appeal to this type of processing include those focused on social norms, framing, and tailoring. “Automatic processing” refers to choices made on the basis of an automatic response, without the intervention of cognition. Tactics for interventions that appeal to this type of processing include emotional shortcuts, priming, and nudging.

A review of empirical studies in the context of water conservation suggests that interventions designed to stimulate semireflective processing (i.e., using simple cues that help people with making choices) can support long-term behavior change (Koop et al., 2019). Based only on small, short-duration studies, the same review also suggests that interventions intended to stimulate automatic cognitive processes using emotional cues, primes, and nudges have the potential to produce behavior change (Koop et al., 2019). Similarly, a meta-analysis of mechanisms for promoting household action on climate change (i.e., choice architecture, social comparison, information, appeals, and engagement) shows that those using social architecture approaches (i.e., nudges) have the highest effect sizes (Nisa et al., 2019).

Understanding the types of cognitive processing being targeted will help with the design of interventions. Most recently, researchers have begun to create study designs that take more than one processing type into account.

Interventions fall into broad categories in terms of how they operate. Research across the six related domains has produced a range of findings about the efficacy and effectiveness of specific kinds of interventions. These findings suggest that tailoring combinations of interventions to particular circumstances is important because the strengths and weaknesses of interventions may be more or less significant in different contexts. Several scholars have proposed ways of categorizing types of interventions designed to change behaviors to facilitate identifying and leveraging their relative strengths. The committee adopted the following categorization of the types of interventions based on terminology used frequently in other domains (see, e.g., Nisa et al., 2019)4 to organize and interpret and compare the results of the studies (see definitions in Appendix G):

- appealing to values,

- engaging consumers,

- evoking social comparison,

- providing feedback,

- providing financial incentives,

- modifying the choice architecture (i.e., nudges), and

- providing how-to information.

Applying this categorization illustrates that the types of interventions identified as most effective in the literature from the six domains are varied, and suggests that many types can be effective depending on the context. For example, Nisa and colleagues (2019) found that, overall, interventions

___________________

4Appendix E describes other categorizations proposed (e.g., by construct, by strategy, by process).

in the categories of modifying the choice architecture (i.e., nudges, removing external barriers) and evoking social comparison (i.e., comparing one’s behavior with others) were more efficacious for behavior change than such traditional interventions as providing information (e.g., statistics, simple messages, energy labels); appealing to values (e.g., requests to change behavior for the benefit of humanity); and engaging consumers (e.g., targeting goal setting, implementation intentions). A deeper exploration of this literature (see Appendix E) suggests that each of the seven types of intervention can play an important role but that nuances need to be considered.

Caution is necessary in attributing effectiveness to any particular type of intervention: each is most effective when targeted appropriately to context, populations, and goals. For example, although information interventions are generally less effective than other types, communication campaigns providing information about health can be effective, particularly when aimed at changing one-time or infrequent behaviors, but generally are less effective at changing habits (Snyder, 2007). Research on financial incentives to motivate behavior also illustrates the need to understand the full effects of an intervention, including short- and long-term effects. While research suggests that using financial incentives to stimulate behavior change can be effective (e.g., for changing diets [Niebylski et al., 2015] or for reducing solid waste disposal at the residential level [Skumatz, 2008]), over the long term it may negatively affect individuals’ intrinsic motivation to change the targeted behavior (Delmas et al., 2013; Soderholm, 2010).

REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE FROM THE FOOD WASTE LITERATURE

The committee conducted an extensive literature search to identify studies that assessed the effects of interventions intended to reduce food waste at the consumer level. Taking into consideration the upstream and system-level aspects of food waste, we examined interventions that target both individuals directly and components of the food supply chain, including such businesses as food service venues and food retailers. We developed a procedure for sorting the results of this search and assessing the strength of the evidentiary support for the findings it yielded. The next step was to consider the fit of the MOA framework to this body of work. We organized studies according to the above seven types of interventions and assessed the evidence.

Process for Reviewing the Literature

The literature search initially covered the period 2005 through June 2019, and was augmented thereafter as committee members and staff

became aware of additional qualifying studies. The search yielded a total of 64 peer-reviewed intervention studies. Some non-peer-reviewed literature on relevant interventions was also examined. (Appendix B provides a more detailed description of the literature search.)

Quality Criteria Applied to Peer-Reviewed Studies

The quality of the studies identified varied substantially, so the committee established four criteria, which align with evidence standards endorsed for research in prevention science (Gottfredson et al., 2015), for assessing the weight we would give each study in interpreting the evidence:

- Was an intervention implemented?

- Was wasted food measured (not just changes in intentions to waste or in behaviors that could reduce food waste)?

- Did the study design permit analyses to isolate the causal effect of the intervention?

- Were statistical analyses adequate for determining statistical significance?

Table 4-1 shows how these criteria were applied. We designated studies that met all four criteria as tier 1, and those that met fewer than four criteria as tier 2.

The committee used criterion 1 (an intervention was implemented) to ensure that it would rely only on studies assessing newly implemented practices, rather than comparisons across sites or groups with different preexisting practices. Studies that meet criterion 2 (wasted food was measured, either directly or using such proxies as diaries) yield stronger evidence because they describe interventions that produced actual changes in behavior.

TABLE 4-1 Criteria for Identifying Tier 1 Studies

| Criteria (All Must Be Met for Tier 1) | Examples of Not Meeting Criterion |

|---|---|

|

Comparing locations with preexisting differences in practices where one practice matches the proposed intervention |

|

Intended waste was measured; actions that could lead to reduced waste were measured (e.g., leftover bag use, ugly food purchases) |

|

Pre- vs. postintervention analysis without an appropriate control group |

|

Study fails to assess statistical significance |

NOTE: Tier 2 studies fail to meet at least one of these four criteria.

Considerable research has shown that estimated effect sizes in studies of interventions aimed at altering household behaviors are significantly larger when the outcomes measured were changes in attitudes or intentions rather than actual behaviors (Andreasen, 2012; Webb and Sheeran, 2006).

Criterion 3 (causal effect can be attributed) excludes studies whose design and implementation do not permit clear identification of causal effects. One frequently observed design that fails to meet criterion 3 involves pre/post comparisons of food waste with no control group. Without well-designed control groups, there could be many reasons for observed reductions in food discards (e.g., seasonal changes in rates of food waste that happen to coincide with implementation of an intervention). Criterion 4 (adequate statistical analyses) limits the studies on which the committee relied to those in which the calculation and reporting of effect sizes are consistent with established practice and suitably clear for assessing the evidence; that is, statistical significance and relevant magnitudes can be ascertained from the published material.

Together, these four criteria helped the committee identify evidence supporting claims that interventions demonstrated merit across several dimensions of validity (internal, external, construct, and statistical conclusion validity; see Shadish et al. [2002]). We note that use of the term “quality” for tier 1 studies is not intended to imply that studies outside this tier are necessarily of low quality or not informative; researchers may use diverse approaches and methods depending on various factors, including their goals and resources.

Comments on the Evidence

The interventions covered in the committee’s review were designed to operate in a range of contexts: at the household level; at establishments where individuals eat (i.e., food service settings); at other levels of the supply chain that could influence consumer behavior (e.g., food retailers or farmers’ markets); and in some cases, outside the food supply chain (e.g., community, media). About three-quarters of the studies were conducted outside the United States, so we judged their applicability to the U.S. context based on the similarity of relevant cultural and value aspects (e.g. the value of food).

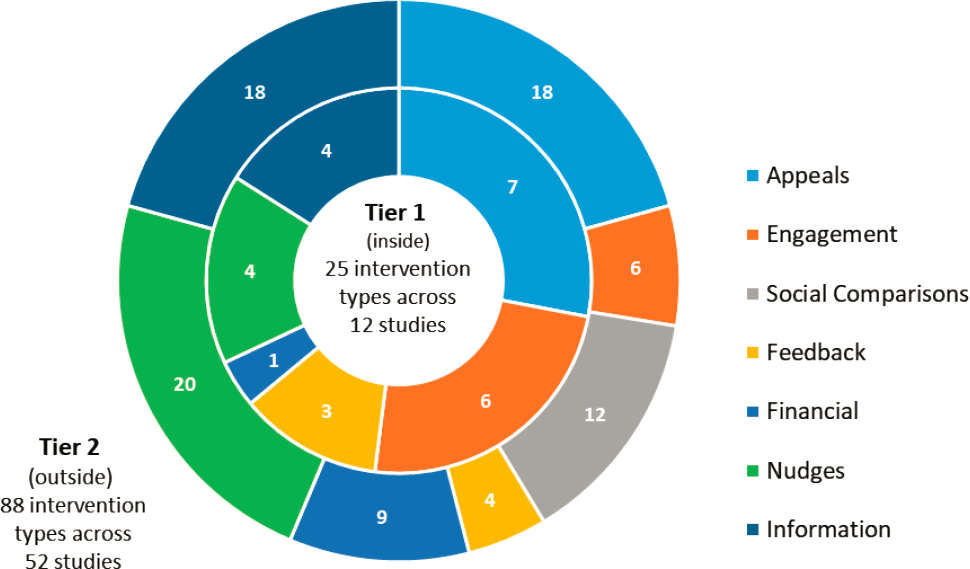

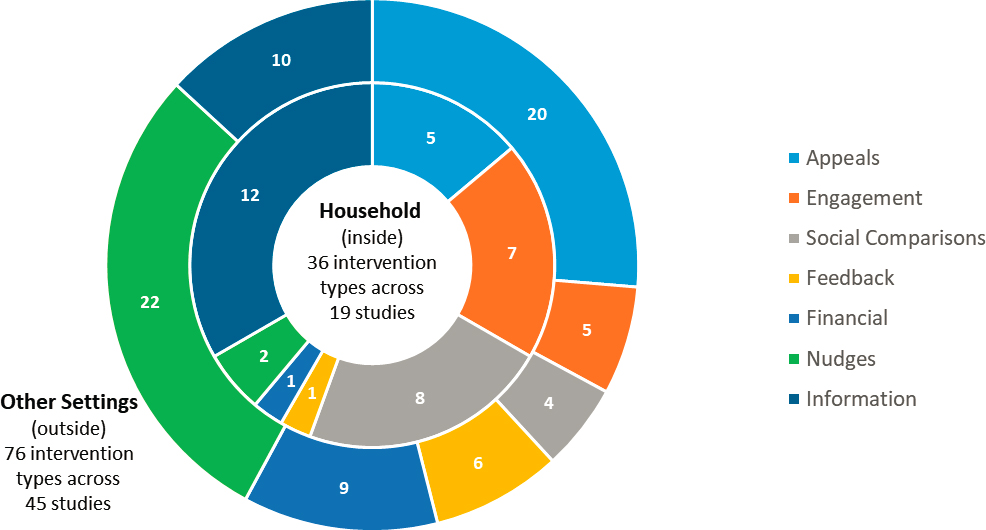

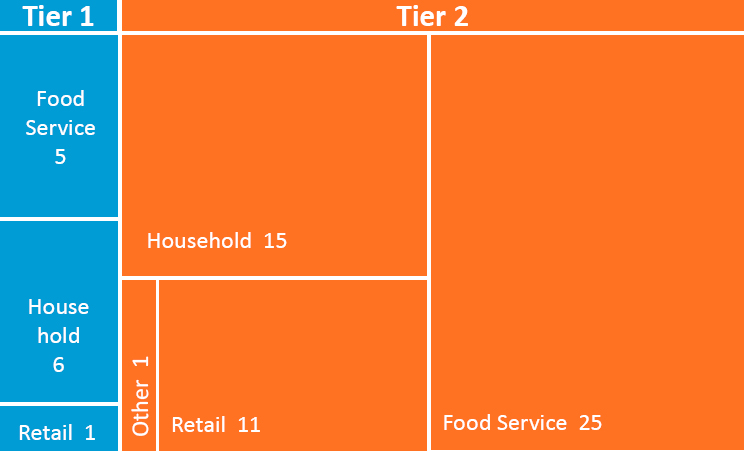

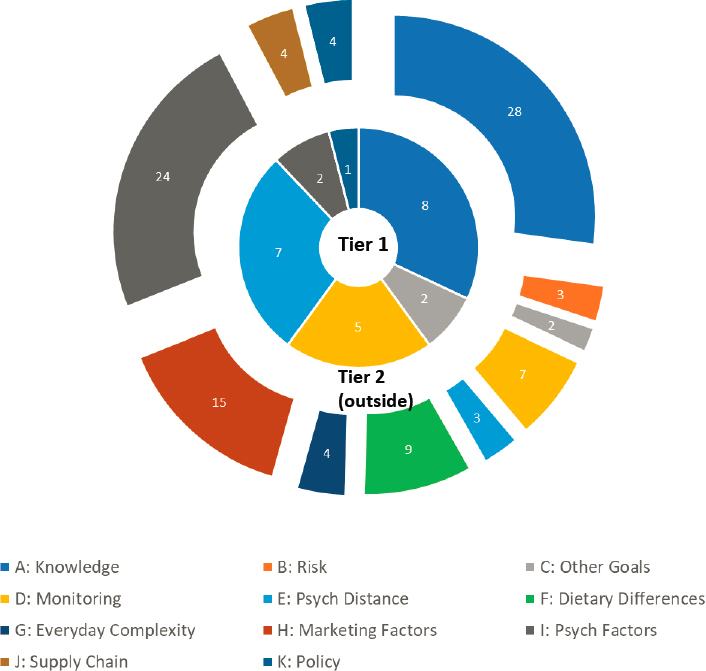

Figure 4-1 shows the distribution of peer-reviewed studies by tier and intervention setting. There are five times as many tier 2 studies as tier 1 studies, and about half of the studies in each tier focus on food service settings. All the studies considered are described in Appendix D.

The empirical studies that meet the committee’s inclusion criteria all rely on linear approaches to assessment instead of the systems approach endorsed by the committee (see Chapter 1). Because of the burden of

implementation and tracking, most intervention studies focus on a single stage in the consumer process (e.g., purchase, home meal preparation, consumption, discard) rather than on circumstances that involve multiple components of the food system. Therefore, although these studies suggest causal relationships between interventions and reductions in food waste, they do not include assessment of the more complex feedbacks that would be expected from interventions designed with a systems approach. However, many of the studies examine designs that make use of more than one intervention type; many also address more than one of the three elements of the MOA framework. Although the available studies do not address multiple stages within the food supply chain, they do support the idea that multiple strategies may reinforce each other in an effort to effect change.

The committee also reviewed key modeling studies, which, rather than providing empirical assessments of interventions, depict how interventions may affect food waste and other variables of interest across the food supply chain. Modeling studies are particularly useful for exploring potential systems-level effects. Such effects include spillovers (such as impacts on other parts of the food supply chain or society) and unintended effects (such as shifting waste from one part of the system to another). Modeling studies also support predictions about behavioral and organizational responses that arise at points in the food supply chain not directly targeted by an intervention, as well as the associated costs and benefits. Typically, such studies are based on assumptions about the structural relationships among key system

components and rely on previously available empirical data to calibrate these relationships. They can generate fresh insights and broaden the focus from the effects of singular interventions to wider impacts and multiple outcomes. For example, the broadest modeling study found (Chitnis et al., 2014) explores system-wide rebound effects of food waste reduction efforts together with other proenvironmental behaviors that households might undertake. The authors assess the implications of food waste reduction efforts for greenhouse gas emissions by estimating from secondary data how households would spend the money they save by wasting less food.

In addition, the committee reviewed selected non-peer-reviewed (gray literature) intervention and modeling studies. We considered these studies as additional information in our overall discussion of the evidence.

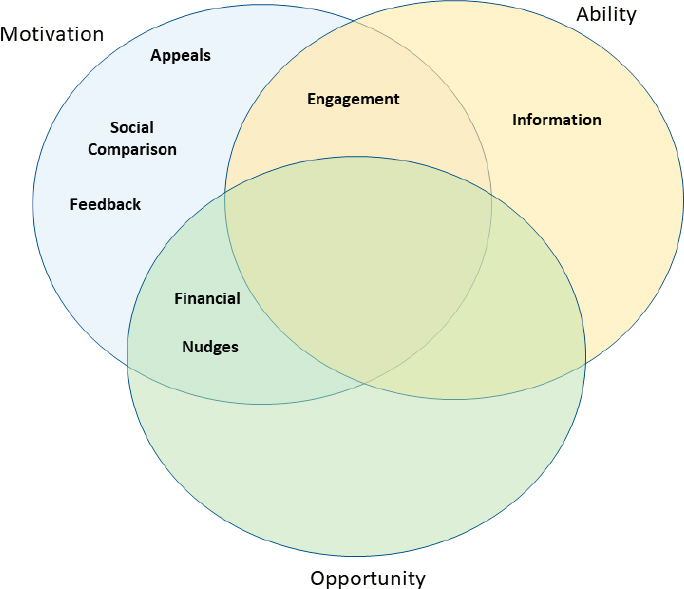

Applying the MOA Framework

The committee next considered the relationship between the seven intervention types listed earlier (appealing to values, engaging consumers, evoking social comparison, providing feedback, providing financial incentives, modifying the choice architecture [i.e., nudges], and providing how-to information) and the three elements of the MOA framework (see Figure 4-2). Several intervention types are broad enough to be linked with two or more elements of this framework. For example, nudges can affect both opportunity (e.g., by reducing plate size) and motivation (e.g., by changing when school meals are served relative to children’s recess periods).

The MOA framework highlights the importance of implementing interventions that address more than one of its three elements to support behavior change. For example, as discussed previously, although interventions that increase motivation can change behavior, motivation alone is generally insufficient to lead to participation in that behavior. When ability and opportunity to change behavior are not present, interventions that increase them also are needed. Thus, for example, even if individuals wish to reduce food waste, refrigerators that are set at the wrong temperature can increase the perishability of food, making it more difficult to translate that motivation into a desired outcome.

Another advantage of the MOA framework, emphasized in Chapter 1, is that it allows for consideration of automatic behaviors, such as habits and norms that are not reliant on explicit individual motivation (Kwasnicka et al., 2016). That is, when motivation, opportunity, or ability is low, consumers are likely to be influenced by factors related to routine, choice context, nonconscious factors, or social norms, and that addressing individual, group, and societal cues will increase the chances of achieving sustained behavioral change.

NOTE: The placement of an intervention type in the intersection of multiple circles usually means that the category encompasses some interventions within one element and some within another. However, some interventions may affect multiple elements simultaneously.

Review of Interventions by Type

Figure 4-3A shows the distribution of intervention types by the strength of the evidence supporting them (by study tier) while Figure 4-3B shows their distribution by study setting (at or away from home). Together, these figures reveal several patterns. First, about half of the studies reviewed address multiple interventions, and therefore, the count of intervention types exceeds the number of studies (e.g., 25 intervention types are addressed in the 12 tier 1 studies; see Figure 4-3A). While this multi-intervention approach may be beneficial, many of these studies do not allow for the segmentation of results to yield clear insight into the roles of the different intervention types. Second, both figures highlight the dominance of intervention types that operate to increase consumer motivation (i.e., appeals, social comparison, feedback): more than half the studies reviewed feature at least one intervention linked to motivation. Third, among studies of

interventions focused on opportunity (i.e., nudges), the majority fall into tier 2 and were conducted outside the home. Studies of interventions focused on ability (e.g., information messages to build knowledge and skills) focus primarily on households.

Overall, this body of work addresses primarily intervention efficacy (the extent to which an intervention produces the desired results under ideal circumstances) and, to a lesser extent, effectiveness (the extent to which an intervention is shown to achieve its aims in laboratory conditions or real-world settings). Few of the studies explore implementation factors, such as cost, feasibility, and ease of implementation, that play a role in selecting interventions; the need to address this gap is discussed in Chapter 6. Also, few of the studies explore additional systems effects of interventions, such as system-wide feedbacks, rebound effects, and cobenefits or coharms for nonwaste outcomes. None of the studies consider the implications of interventions for income inequality or other distributional concerns.

Appeals

Appeal interventions encourage consumers to change their behavior to achieve a social benefit. Explicit appeals, which request action directly, are distinct from implicit appeals, which do not make a request. Implicit appeals may be based on a presumption that the facts will tap into existing attitudes or values, or may serve as prompts to action by raising awareness. Explicit appeals build on those mechanisms and also activate the human tendency to respond to requests, particularly when they align with values, when the requestor is valued, or when something is owed to the requestor (reciprocity). Twenty-five of the 64 studies reviewed by the committee included appeal interventions: 13 that used explicit appeals, 3 that used implicit appeals, and 9 that used both and other intervention types. The largest number of interventions presented signage or other messaging in food service venues, often in universities. Other interventions provided messages directly to study participants or engaged participants in creating messages; one pair of studies involved delivering messages to the general public.

One tier 1 study (Ellison et al., 2019) found a null effect for the appeal component, and one found an overall null intervention effect (Liz Martins et al., 2016), but it was not possible to isolate the appeal component. All but three of the tier 2 studies found statistically significant impacts, with the magnitude of effect varying. A few tier 2 studies involved comparing appeal interventions with other types, such as providing information (Collart and Interis, 2018) and feedback (Whitehair et al., 2013), with results favorable to appeal interventions. In at least a quarter of the studies, it was not possible to disentangle the results of the appeal intervention from

those of other interventions included in the study. Few studies looked at maintenance of impact across time.

Engagement

Engagement interventions change psychological processes by engaging the consumer in, for example, setting goals, establishing implementation intentions, making a commitment, or increasing mindfulness toward the target behavior. Twelve studies (six in tier 1) featured such interventions, which are often multifaceted, operating through multiple drivers. Thus, the results of this type of intervention may be manifested in a variety of ways. These interventions have a mixed record in delivering significant reductions in food waste, which makes it difficult to provide a summary evaluation. For example, engagement interventions delivered in the home included diverse mechanisms: systematically engaging individuals to reconsider household food routines (Devaney and Davies, 2017, tier 2); providing tools to support changes in meal planning or preparation (Romani et al., 2018, tier 1); and using gamification to accelerate and deepen learning about wasted food (Soma et al., 2020, tier 1).

Several food service interventions were also comprehensive, involving food service personnel and patrons (Strotmann et al., 2017, tier 2) or both food service personnel and student customers (Prescott et al., 2019, tier 1). The results of these studies suggest that interventions aimed at reprogramming base processes that drive food waste hold promise, but the lack of consistent reductions implies that formulating the multiple elements common to this approach may be difficult. Furthermore, the complex and multifaceted nature of these interventions impedes assessment of which individual strategy or subset of strategies drives efficacy.

Social Comparison

Social comparison interventions operate on principles of social influence. Twelve studies, all tier 2, included such interventions. The interventions studied were diverse, focusing on social desirability, public commitment, social media communications, communication of social norms, food sharing, and such situations as workshops in which a peer group might influence behavior. The authors of only three of these studies provide quantitative results that make it possible to distinguish the effects of the social comparison intervention from those of other interventions in the study. Two of these three focused on restaurant leftovers. Hamerman and colleagues (2018) and Stockli and colleagues (2018) found that messages designed to invoke social norms (i.e., saying a majority of patrons request to take food home) were not more effective than informative messages. Hamerman and colleagues

(2018) found that study participants were significantly more likely to request to take home leftovers when they envisioned dining with friends versus dining with someone they wanted to impress. Five of the studies used qualitative or mixed-method approaches, with all but one suggesting that social comparison was beneficial in preventing waste. However, findings from Lazell (2016) echo those from Hamerman et al. (2018), suggesting that the effectiveness of social comparison interventions can depend on participants’ views about what behavior is normative and about the social groups with which they are comparing themselves. Overall, the evidence regarding social comparison interventions is inconclusive, and the research suggests a need for nuanced intervention development and careful selection of social groups for comparison and messaging.

Feedback

Feedback interventions shape targeted behaviors by providing information that reinforces or corrects those behaviors. Seven of the studies reviewed (three tier 1) featured feedback interventions, largely as part of multifaceted interventions implemented in food service settings. Thus, it was difficult to identify the individual impact of the feedback strategies. A common strategy was to offer cafeteria patrons feedback concerning the average waste created by other patrons, although studies using such strategies as part of a multifaceted intervention revealed little success. Personalized feedback, often generated for elementary and middle school students in cafeteria settings as part of a multifaceted intervention, showed some statistically significant effects (e.g., Liz Martins et al., 2016, tier 1; Prescott et al., 2019, tier 1). Feedback delivered among different food service worker stations within a large hospital facility showed promise as part of a multifaceted intervention that significantly reduced waste (Strotmann et al., 2017, tier 2). And a qualitative assessment of the use of home cameras to track waste suggests that such approaches could stimulate waste reduction by invoking feelings of shame (Comber and Thieme, 2013, tier 2). Overall, feedback interventions have a mixed record, with weaker effects when feedback is not individualized.

Financial Incentives

Interventions providing financial incentives alter the monetary consequences of behaviors that can influence the amount of food consumers waste. One tier 1 study in South Korea found financial penalties that increase with amount of wasted food generated at the household level to be more effective at reducing the amount of wasted food than financial penalties tied to community level waste amounts (Lee and Jung, 2017). The

authors, however, noted illegal dumping as a potential unintended consequence. It has been well documented that overall household waste disposal (food plus nonfood waste) declines when households are forced to pay more for additional amounts of waste (Bel and Gradus, 2016). Nine tier 2 studies featured other financial interventions. Most involved comparing the effects of retail price reductions with those of other approaches used to encourage consumers to purchase suboptimal (ugly or expired) food that might otherwise be wasted. These studies yielded statistically significant evidence that price reductions can increase purchase intentions. However, alternative motivational approaches, such as highlighting the environmental consequences of food waste, often yielded changes similar to those seen in purchase intentions or enhanced the effectiveness of price discounts.

Two studies focused on quantity (e.g., large-pack or multipack) discounts (LeBorgne et al. 2018, tier 2; Petit et al., 2019, tier 2). These studies showed that giving consumers information about how such deals can translate to greater waste had less effect on purchase intentions relative to simply lowering unit costs for certain foods. Two studies in food service settings showed mixed results for comparison of the efficacy of imposing fines for excessive plate waste and emphasizing environmental benefits to reduce plate waste (Chen and Jai, 2018, tier 2; Kuo and Shih, 2016, tier 2).

Overall, financial incentives are a promising way to discourage behaviors that are precursors to food waste and to increase motivation for overall home waste reduction. However, linking financial incentives to decision points specific to wasting food may prove difficult, and establishing efficacy and implementation feasibility will require considerable additional research.

Nudges

Nudge interventions alter the choice architecture faced by consumers in a manner designed to encourage targeted behaviors without engaging conscious (reflective) decision making (see Chapter 1). The committee reviewed 24 studies (four tier 1) that involved such interventions, most of which addressed food service settings. The nudge interventions studied operated by means of diverse mechanisms, including shifting perceived quantity, altering appeal, or changing the default/easiest action. The interventions assessed in about 40 percent of the studies focused on shifting consumers’ perceptions of quantity through changes to portion size, package size, plate size, or tray availability. Most of the studies found significant reductions in waste attributable to quantity manipulations, although only two such studies were tier 1. Three studies (Kim and Morawski, 2013, tier 1; Sarjahani et al., 2009, tier 2; Thiagarajah and Getty 2013, tier 2) focused on removal of cafeteria trays, which limits quantity by making it more difficult for

patrons in buffet settings to carry multiple plates. All three of these studies (plus several non-peer-reviewed studies) found significant reductions in plate waste. In contrast, one recent non-peer-reviewed study (Cardwell et al., 2019) found no effect.

Another 40 percent of studies involved altering the appeal of food with the intent of decreasing waste by encouraging increased consumption. Several tier 2 studies enhanced appeal directly by improving meal quality or better matching meal components to patrons’ preferences; a majority of those studies showed a significant reduction in waste for these interventions. Other studies, including two tier 1 studies (Ilyuk, 2018; Williamson et al., 2016), involved nudges to increase appeal less directly, including by altering the quality of the material of the plate used; providing priming messages to subtly enhance the self-esteem of customers considering the purchase of suboptimal foods; making purchasing require more effort to enhance the consumer’s psychological ownership of food; and providing cafeteria meals after recess, when students’ appetites would be greater. All four studies found significant effects.

The remaining studies (all tier 2) involved forcing changes to consumers’ default behaviors. Two studies focused on date labels, with one altering descriptive phrases (e.g., changing “sell by” to “use by”) to stimulate different processing of date information (no effect) and the other removing dates to force different evaluation approaches for product freshness (significant reduction). One study (Manzocco et al., 2017, tier 2) considered how lowering ambient refrigerator temperatures might help consumers discard less produce. Modeling studies also highlight the potential benefits of improving refrigeration design (see details in Appendix D). Extending the time period at which food remains at peak quality is among the most promising approaches to preventing waste at all levels of the food supply chain, and such approaches have particular utility for helping consumers navigate scheduling shifts that prevent using purchased food when planned. Although considerable technological design effort exists in that space, such as packaging, including modeling studies assessing potential impacts, they are seldom tested in interventions that specifically assess the impact on consumer discards; and thus other studies did not qualify for this review. Policies that ban organic waste from landfills can also change default behaviors (Sandson and Broad Leib, 2019), although none of the studies reviewed examined such interventions.

Overall, the evidence for nudge interventions focused on shifting food quantity and appeal is stronger than that for any of the other intervention types, with statistically significant effect sizes being documented in multiple studies of this intervention type. However, the evidence is mixed, dominated by tier 2 studies, and limited in context (studies of nudges were primarily short-run evaluations carried out in buffet settings). Further, the potential

for these interventions to be feasible needs to be considered in light of effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as how the closing of food service venues during the pandemic will affect other practices related to food.

Information

One of the most common and seemingly intuitive approaches to addressing food waste is providing participants with concrete advice aimed at helping them reduce their waste: a tool for action, such as knowledge or skills regarding how to reduce waste. This category is distinct from appeal and feedback interventions, which also provide forms of information; information interventions entail providing only “how-to” information. Intervention designs of this type are often rooted in the theory of planned behavior (see Chapter 1).

The committee’s literature search identified 22 studies that included information interventions, three of which are tier 1 studies. The interventions studied were fairly evenly divided between household and food service settings. In most cases, the guidance provided included multiple how-to tips targeting different strategies for reducing food waste or preserving food longer. The information and tools provided were often designed to be proximate to the point of decision making (e.g., refrigerator magnets and food containers for storage decisions, spreadsheets for use when planning meals). Advice was provided in a variety of modalities, from pamphlets and information packets to films, signage, and social media.

In most cases, the information interventions paired advice with other interventions, such as calls to action, tracking, or communication of social norms. Thus in many of the studies (8 of the 22, including 2 of the 3 tier 1 studies [Liz Martins et al., 2016; van der Werf et al., 2019]), it was not possible to distinguish the effects of the information component itself. The third tier 1 study (Soma et al., 2020) showed a small effect for the information component when the intervention encouraged participants to engage actively with the information through quizzes with rewards, while passive participation or modes that required more coordination to achieve engagement (attending group workshops) failed to produce significant waste reduction.

Six of the tier 2 studies found significant positive effects that could be attributed directly to the information provision. One involved tailoring the information provided based on pretest results, a procedure that significantly improved outcomes (Schmidt, 2016). Two studies found null effects of the information provision (Ahmed et al., 2018; Jagau and Vyrastekova, 2017). In some cases, effects measured reflected intermediate outcomes, such as knowledge. Qualitative studies generally found positive effects for providing information through such means as intensive small-group sessions. The

committee also reviewed two studies (tier 2) where a UK retailer implemented multiple informational and social approaches using communication techniques, with positive effects on food waste (Young et al., 2017, 2018). Several other reports of large-scale information interventions that had not been peer-reviewed also suggested potential positive impacts for information interventions.

In summary, while some studies suggest significant effects may be achieved with simple informational interventions alone, other studies suggest null effects, and long-term impacts must be assessed. Additionally, as the public grows more knowledgeable about wasted food, the impact of informational approaches may be reduced.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Interventions to address consumer-level food waste address different components of the food system (e.g., food retail, cafeterias in schools and higher education settings, hospitals, and restaurants; households; and government policies) using a wide range of mechanisms. The increased attention to food waste over the past decade (see Chapter 2) and the growing body of research on the drivers of consumer behavior in the food waste and related domains may give the impression that much is already known about how to promote behaviors that reduce food waste. Yet as the evidence discussed in this chapter demonstrates, the literature evaluating interventions to reduce food waste is relatively small, and high-quality experiments are sparse, although rapidly developing. The broader body of research on interventions in the six related domains considered by the committee and the smaller, emerging body of work specific to food waste, are being carried out in a variety of fields and research traditions (see Chapter 1). Thus, integrating and assessing the findings from the literature is challenging. In addition, differences in terminology make it difficult to compare findings in the food waste literature with those from the six related domains. Nevertheless, many tantalizing findings suggest the potential for impacts of high magnitude.

In the research from the six related domains, the committee identified evidence about interventions that appeared to be effective in changing behavior, based on broad findings from across populations and contexts (see Appendix E). Some of those findings were also identified in the emerging food waste literature and they are discussed below.

Findings about Interventions

The Value of Multifaceted Interventions

Research from the six related domains demonstrates that in general, multifaceted interventions that leverage more than one mechanism may be more effective than those that rely on a single mechanism. Most of the interventions studied in the food waste literature were multifaceted in that they included components reflecting more than one of the seven types of interventions discussed in this chapter—for example, an intervention that both provided information and appealed to consumers’ values related to the information given.

One reason a multifaceted intervention is likely to be more effective than a unitary approach is that food waste, like many other behaviors, is driven by multiple influences. The components of the former interventions thus may reinforce each other and amplify the overall power of the effort to effect change. Moreover, the effects of multifaceted interventions can be augmented because the combined interventions can address more than one of the three elements of the MOA framework. Additional benefits can come from combining interventions effective at initiating behaviors with those effective at sustaining behaviors. These observations do not indicate that multifaceted interventions are essential in all case. For example, unitary interventions from the nudge category, such as tray removal and plate size reduction, leverage automatic decision processes and yield significant reductions in waste on their own. Moreover, the food waste literature is not yet substantial enough to support a firm conclusion that bundled interventions are uniformly more effective than single interventions. Nonetheless, the existing evidence certainly suggests the value of integrating multiple intervention types.

The Value of Understanding Cognitive Processes

As mentioned in Chapter 1, early theories characterized human behavior as being predominantly conscious and driven by reason, while more recent work has demonstrated that individual behaviors are responsive to both reflective and automatic processes. The seven intervention types can be thought of in terms of the behavioral processes they target, which fall on a continuum ranging from reflective to semireflective to automatic. Reflective processes can be targeted by interventions featuring information, appeals, feedback, engagement, and financial incentives, in which the objective is for consumers to reflect and reason about their behaviors and decide to alter them. Semireflective processes can be targeted by interventions featuring engagement, social comparison, financial incentive, and in

some cases, nudges (e.g., plate size as a cue for food acquisition in a buffet). These interventions, which often operate by altering consumers’ heuristics, begin to shape behaviors more subtly. Automatic processes are commonly targeted by social comparison and nudge interventions, which are designed to change behavior by altering choice architecture, removing barriers to behavior, or provoking instantaneous responses without necessarily engaging a consumer’s reflective processes. As discussed in Chapter 3, knowledge of the drivers of specific food waste behaviors, as well as understanding of the cognitive processes (e.g., reflective or automatic) and elements of the MOA framework involved in those behaviors, can guide the design of future interventions.

Relative Effectiveness of Intervention Types

The types of interventions that have been most effective in the six related domains are varied, suggesting that many types can be effective depending on contextual factors. Among the seven intervention types, those focused on choice architecture (i.e., nudges, removing external barriers) and social comparison (i.e., comparing one’s behavior with that of others) have been found to be more efficacious than the other types. However, factors related to the circumstances and domains in which the various intervention types are implemented influence how effective they are. For example, each is most effective when targeted appropriately to context and when such factors as the duration of the intervention, the content of messages, and integration with other interventions are considered. It is also important to consider the target population: for example, financial incentives may be effective with some consumers, but financial disparities can alter how such an intervention is experienced.

The existing evidence does not support an assertion that any interventions are effective across domains or support the identification of combinations of intervention types that are more effective at reducing consumer-level food waste in all contexts and for all populations. For example, while the use of nudges in away-from-home settings (e.g., trayless cafeterias) appears to be effective, nudges in households might require additional strategies (e.g., to motivate consumers to purchase smaller plates). The committee emphasizes that only 11 peer-reviewed food waste studies met all four of its tier 1 evaluation criteria. No intervention types are yet supported by a suite of well-executed studies, carried out with multiple populations and in varied contexts over a suitable duration to support strong conclusions.

CONCLUSION 4-1: Existing research does not yet provide the highest level of support for widespread adoption of specific interventions in multiple contexts. However, there is evidence that some interventions

may be efficacious at reducing food waste at the consumer level in the short term, and suggestive evidence of the potential benefits of other types of interventions.

Findings supporting this conclusion are summarized in Table 4-2. The committee urges caution, however, in generalizing about the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions based on these findings. The effectiveness of any intervention will depend on its being well designed, tailored to the context and with consideration of various elements of the MOA framework, and well implemented. The additional research needed to evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of promising interventions is discussed in Chapter 6.

Limitations and Gaps in the Evidence Base

Although the rapid pace of intervention development and competition for the limited funds available to address food waste can make evaluation of interventions appear to be a luxury, evaluation is essential to further progress in reducing consumer-level food waste. The committee notes multiple limitations across the reviewed literature, with even the best available tier 1 studies suffering from such limitations as a lack of long-term evaluation and lack of replication that are impeding progress. These limitations are summarized in this section. The committee’s specific research recommendations are presented in Chapter 6.

CONCLUSION 4-2: Although many of the food waste studies reviewed met high standards of quality, the current body of literature has limitations that need attention in future research designs. Those limitations include limited field-based research; the small scale of the studies; lack of long-term evaluation; the diverse approaches used in measuring wasted food; lack of a systems approach, including implementation of diverse intervention types and measurement of trade-offs; lack of attention to distributional and equity considerations; and limited consideration of implementation. Replication in a range of U.S. populations and contexts, which would increase generalizability, is critically lacking.

Because context shapes behavior and is therefore a key factor to consider in studying behavior change, research conducted in the field (e.g., food service and retail store settings) can provide essential insights. On the other hand, field research presents practical difficulties that do not affect laboratory and desk-based research, such as the fact that establishing control groups is not always feasible. Moreover, many food waste interventions are designed to be implemented in settings, such as school cafeterias, food

TABLE 4-2 Types of Interventions and Examples with Evidence (Tier 1 Studies) and Suggestive Evidence (Tier 2 Studies) of Efficacy in Reducing Food Wastea,b

| Intervention | Examples |

|---|---|

| Appeals |

With evidence:

|

With suggestive evidence:

|

|

| Engagement |

With evidence:

|

| Social Comparisons |

With suggestive evidence:

|

| Feedback |

With suggestive evidence:

|

| Intervention | Examples |

|---|---|

| Financial |

With evidence:

|

With suggestive evidence:

|

|

| Nudges |

With evidence:

|

With suggestive evidence:

|

|

| Information |

With evidence:

|

With suggestive evidence:

|

a Tier 1 studies met four criteria: an intervention was implemented, wasted food was measured, causal effect can be attributed, and statistical analysis was adequate. Tier 2 studies failed to meet at least one of those four criteria.

b The committee urges caution in extrapolating the information in this table to generalized statements about the efficacy and effectiveness of these interventions, which will depend on many other factors.

stores, or restaurants that are not accustomed to research partnerships and may not view evaluation as a priority.

Short-Term, Small-Scale Studies

The food waste literature contains very few studies that assess medium- and long-term effects. Most studies evaluate effects on time scales of hours to weeks, but meaningful change in food waste behavior requires impacts on the scale of many years. Moreover, when assessment is only short term, intermittent waste events (e.g., freezer cleanouts) that can dominate total household waste levels may be missed (Parizeau et al., 2015). It is particularly important to replicate small studies that yield intriguing findings, including intervention opportunities that tap into rarely discussed change mechanisms, using longer timeframes and other methodological improvements.

Diverse Approaches to Measuring Wasted Food

Measuring change in the actual waste of food can be costly and presents logistical and methodological challenges. As a result, many studies use alternative outcome measures with varying levels of reliability and validity. In addition, many studies focus on intentions rather than actual wasted food. Findings from the literature in the six related domains indicate clearly that intentions are not a valid proxy for actual behavior.

Lack of Studies Addressing the Full Array of Drivers or Intervention Types by Applying a Systems Approach

Comparing the interventions studied against the drivers of food waste that have been identified in the literature reveals important gaps in the interventions examined. One such gap is that while the majority of research on drivers has focused on behaviors that occur at home, the intervention research addresses largely behavior that occurs away from home, most likely because easier access to consumers in public spaces facilitates both implementation of interventions and evaluation. The committee also notes that interventions related to motivation have been researched more thoroughly relative to interventions related to opportunity and ability. While all 11 of the summative drivers discussed in Chapter 3 have been explored through tier 2 intervention studies, only two of them were components of interventions studied in tier 1 research (see Figure 4-4).

A different approach to identifying gaps in the intervention literature is to consider the types of interventions that have been evaluated in the context of a well-known framework of systems change (Meadows, 1999,

NOTES: Many interventions map to multiple drivers. See Chapter 3 for the list of and descriptions for each summative driver. The letters in the legend correspond to those assigned to the summative drivers in Chapter 3.

2008). Most interventions studied (about two-thirds) focus on the element in that framework of building individual capacity, with the remainder divided among the categories considered more likely to promote more systematic change (design, information flows, rules and structures, and leadership). However, the committee notes that some of the higher-order systems change processes in this framework (such as those oriented toward shifting rules and structures and leadership) would be relatively unlikely to be addressed through formal interventions in general, and that if they were, it could be challenging if not impossible to evaluate the impacts on such processes using traditional evaluation approaches such as those reviewed in this chapter.

Interventions can also be considered in the context of Mourad’s (2016) taxonomy of “strong” and “weak” prevention. “Weak” prevention is depicted as seeking to change individuals, processes, and technologies without fundamental systemic change, and is generally geared toward efficient management of existing surplus across the supply chain and by consumers. By contrast, “strong” prevention interventions address root-cause factors, working to shift patterns of unsustainable production and consumption. Interventions targeting buffets provide one way to think about the distinction between weak and strong prevention, and highlight the importance of spaces and structures that facilitate waste. An all-you-can-eat buffet has a built-in structure for overconsumption. While most buffet interventions target consumer behavior within such facilities (e.g., reducing plate sizes), one type of strong intervention might be to redesign this model of dining.

Lack of Attention to Trade-offs and Implementation of Interventions

The empirical studies that met the committee’s inclusion criteria included scarcely any consideration of implementation, feasibility, or cost-effectiveness. That is, while efficacy was explored, the data collection did not encompass effectiveness. In addition, only some of the modeling studies reviewed, and some other studies and reports that did not meet the committee’s inclusion criteria, consider or address potential trade-offs, cobenefits, or spillover effects of interventions (e.g., licensing or rebound effects). For example, the relationship among food waste, portion sizes, and obesity needs to be explored because the objectives of reducing waste and eating smaller portions for health reasons may be at odds. Similarly, improper handling of food in leftover bags can compromise food safety. Other tradeoffs include effects on income inequality or other distributional effects (see below). Such information is critical for those selecting and adapting interventions for implementation, and remains a priority for future research.

Lack of Attention to Distributional and Equity Considerations

The committee highlights the importance of both assessing the inequity in the impacts of food waste and also accounting for inequities when designing food waste reduction interventions. When designing interventions, it is important to consider the affordability and feasibility of targeted behaviors across diverse income levels, household sizes, languages spoken, and other factors. It is also necessary to assess the effects of interventions on those not directly targeted, including food service staff (some interventions create extra work, such as in washing dishes, which might need to be compensated) and recipients of donated food (the amount and quality of such food may change as businesses shift their practices).

Food waste prevention interventions need to be designed carefully so they do not exacerbate existing social inequities. For example, interventions promoting the purchase of goods that may be perceived as of lesser quality even if they are not (e.g., foods that are near their labeled expiration date, have damaged packaging, or are aesthetically unpleasing) can cause insult, particularly when these foods are promoted at lower prices or distributed in food assistance programs. On the positive side, interventions aimed at decreasing food waste could address inequities in opportunity and ability, such as by supporting the upgrading of the quality of refrigerators or providing more appealing food choices in school food or food assistance programs.

Potential for Generalizability

Only about one-quarter of the intervention studies reviewed by the committee were conducted in the United States. Thus, the research base provides limited evidence useful for targeting interventions to specific U.S. contexts based on such factors as demographics, policy, infrastructure, and geography. As the body of evidence matures, it will be critical to increase the testing of interventions outside of the United States. As explained in this chapter, interventions may affect behavior differently in different contexts: for example, smaller plates may be experienced differently in the home, where norms of taking seconds may be more common, than in a restaurant. Additionally, some of the studied interventions focus on building motivation while relying implicitly on the existence of opportunity and ability. But as noted, opportunity and ability factors are not distributed equally across the population, for reasons including income, geography, and preexisting equipment. Thus it will be important to expand the research base to diverse contexts and scales to identify interventions with the greatest impact and fewest unintended consequences.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, S., C.B. Shanks, M. Lewis, A. Leitch, C. Spencer, E.M. Smith, and D. Hess. 2018. Meeting the food waste challenge in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 19(6):1075-1094.

Andreasen, A.R. 2012. Rethinking the relationship between social/nonprofit marketing and commercial marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 31(1):36-41.

Bel, G., and R. Gradus. 2016. Effects of unit-based pricing on household waste collection demand: A meta-regression analysis. Resource and Energy Economics 44:169-182.

Cardwell, N.T., C. Cummings, and M. Kraft. 2019. Toward cleaner plates: A study of plate waste in food service. Available: https://www.nrdc.org/resources/toward-cleaner-plates-study-plate-waste-food-service.

Chen, H.S., and T.M.C. Jai. 2018. Waste less, enjoy more: Forming a messaging campaign and reducing food waste in restaurants. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism 19(4):495-520.

Chitnis, M., D. Angela, S. Steve, K.F. Steven, and J. Tim. 2014. Who rebounds most? Estimating direct and indirect rebound effects for different UK socioeconomic groups. Ecological Economics 106(106):12-32.

Collart, A.J., and M.G. Interis. 2018. Consumer imperfect information in the market for expired and nearly expired foods and implications for reducing food waste. Sustainability (Switzerland) 10(11).

Comber, R., and A. Thieme. 2013. Designing beyond habit: Opening space for improved recycling and food waste behaviors through processes of persuasion, social influence and aversive affect. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 17(6):1197-1210.

Cox, J., S. Giorgi, V. Sharp, K. Strange, D.C. Wilson, and N. Blakey. 2010. Household waste prevention: A review of evidence. Waste Management and Research 28(3):193-219.

Delmas, M.A., M. Fischlein, and O.I. Asensio. 2013. Information strategies and energy conservation behavior: A meta-analysis of experimental studies from 1975 to 2012. Energy Policy 61:729-739.

Devaney, L., and A.R. Davies. 2017. Disrupting household food consumption through experimental homelabs: Outcomes, connections, contexts. Journal of Consumer Culture 17(3):823-844.

Ellison, B., O. Savchenko, C.J. Nikolaus, and B.R.L. Duff. 2019. Every plate counts: Evaluation of a food waste reduction campaign in a university dining hall. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 144:276-284.

Gottfredson, D.C., T.D. Cook, F.E. Gardner, D. Gorman-Smith, G.W. Howe, I.N. Sandler, and K.M. Zafft. 2015. Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: Next generation. Prevention Science 16(7):893-926.

Hamerman, E.J., F. Rudell, and C.M. Martins. 2018. Factors that predict taking restaurant leftovers: Strategies for reducing food waste. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 17(1):94-104.

Ilyuk, V. 2018. Like throwing a piece of me away: How online and in-store grocery purchase channels affect consumers’ food waste. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 41:20-30.

Jagau, H.L., and J. Vyrastekova. 2017. Behavioral approach to food waste: An experiment. British Food Journal 119(4):882-894.

Kim, K., and S. Morawski. 2013. Quantifying the impact of going trayless in a university dining hall. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 7(4):482-486.

Koop, S.H.A., A.J. Van Dorssen, and S. Brouwer. 2019. Enhancing domestic water conservation behaviour: A review of empirical studies on influencing tactics. Journal of Environmental Management 247:867-876.

Kuo, C., and Y. Shih. 2016. Gender differences in the effects of education and coercion on reducing buffet plate waste. Journal of Foodservice Business Research 19(3):223-235.

Kwasnicka, D., S.U. Dombrowski, M. White, and F. Sniehotta. 2016. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review 10(3):277-296.

Lazell, J. 2016. Consumer food waste behaviour in universities: Sharing as a means of prevention. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15(5):430-439.

Le Borgne, G., L. Sirieix, and S. Costa. 2018. Perceived probability of food waste: Influence on consumer attitudes towards and choice of sales promotions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 42:11-21.

Lee, S. and K. Jung. 2017. Exploring effective incentive design to reduce food waste: A natural experiment of policy change from community based charge to RFID based weight charge. Sustainability 9:1-17.

Liz Martins, M., S.S. Rodrigues, L.M. Cunha, and A. Rocha. 2016. Strategies to reduce plate waste in primary schools—experimental evaluation. Public Health Nutrition 19(8):1517-1525.

Ma, J., and K.W. Hipel. 2016. Exploring social dimensions of municipal solid waste management around the globe: A systematic literature review. Waste Management 56:3-12.

Manzocco, L., C. Lagazio, M. Alongi, M.C. Nicoli, and S. Sillani. 2017. Effect of temperature in domestic refrigerators on fresh-cut iceberg salad quality and waste. Food Research International 102(102):129-135.

Marteau, T.M. 2017. Towards environmentally sustainable human behaviour: Targeting nonconscious and conscious processes for effective and acceptable policies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 375(2095).

Meadows, D.H. 1999. Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. Hartland, VT: Published by the Sustainability Institute.

Meadows, D.H. 2008. Thinking in systems: A primer. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Michie, S., M.M. van Stralen, and R. West. 2011. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science 6:42.

Mourad, M. 2016. Recycling, recovering and preventing “food waste”: Competing solutions for food systems sustainability in the United States and France. Journal of Cleaner Production 126:461-477.

Niebylski, M.L., K.A. Redburn, T. Duhaney, and N.R. Campbell. 2015. Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition 31(6):787-795.

Nisa, C.F., J.J. Belanger, B.M. Schumpe, and D.G. Faller. 2019. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nature Communications 10(1):4545.

Parizeau, K., M. von Massow, and R. Martin. 2015. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Management 35:207-217.

Petit, O., R. Lunardo, and B. Rickard. 2019. Small is beautiful: The role of anticipated food waste in consumers’ avoidance of large packages. Journal of Business Research 113:326-336.

Prescott, M.P., X. Burg, J.J. Metcalfe, A.E. Lipka, C. Herritt, and L. Cunningham-Sabo. 2019. Healthy planet, healthy youth: A food systems education and promotion intervention to improve adolescent diet quality and reduce food waste. Nutrients 11(8).

Romani, S., S. Grappi, R.P. Bagozzi, and A.M. Barone. 2018. Domestic food practices: A study of food management behaviors and the role of food preparation planning in reducing waste. Appetite 121:215-227.

Samdal, G.B., G.E. Eide, T. Barth, G. Williams, and E. Meland. 2017. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults: Systematic review and meta-regression analyses. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14(1).

Sandson, K., and E. Broad Lieb. 2019. Bans and Beyond: Designing and Implementing Organic Waste Bans and Mandatory Organics Recycling Laws. Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic; Center for EcoTechnology. Available: https://www.chlpi.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/12/Organic-Waste-Bans_FINAL-compressed.pdf.

Sarjahani, A., E.L. Serrano, and R. Johnson. 2009. Food and non-edible, compostable waste in a university dining facility. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 4(1):95-102.

Schmidt, K. 2016. Explaining and promoting household food waste-prevention by an environmental psychological based intervention study. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling 111(111):53-66.

Shadish, W.R., T.D. Cook, and D.T. Campbell. 2002. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Sharp, V., S. Giorgi, and D.C. Wilson. 2010. Delivery and impact of household waste prevention intervention campaigns (at the local level). Waste Management and Research 28(3):256-268.

Skumatz, L.A. 2008. Pay as you throw in the US: Implementation, impacts, and experience. Waste Management 28(12):2778-2785.

Snyder, L.B. 2007. Health communication campaigns and their impact on behavior. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(2 SUPPL.):S32-S40.

Soderholm, P. 2010. Environmental Policy and Household Behavior: Sustainability and Everyday Life. Abingdon, UK: Earthscan.

Soma, T., B. Li, and V. Maclaren. 2020. Food waste reduction: A test of three consumer awareness interventions. Sustainability 12:907-926

Stockli, S., M. Dorn, and S. Liechti. 2018. Normative prompts reduce consumer food waste in restaurants. Waste Management 77:532-536.

Strotmann, C., S. Friedrich, J. Kreyenschmidt, P. Teitscheid, and G. Ritter. 2017. Comparing food provided and wasted before and after implementing measures against food waste in three healthcare food service facilities. Sustainability (Switzerland) 9(8).

Sweet, S.N., and M.S. Fortier. 2010. Improving physical activity and dietary behaviours with single or multiple health behaviour interventions? A synthesis of meta-analyses and reviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7(4):1720-1743.

Thiagarajah, K., and V.M. Getty. 2013. Impact on plate waste of switching from a tray to a trayless delivery system in a university dining hall and employee response to the switch. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 113(1):141-145.

Thomson, C.A., and J. Ravia. 2011. A systematic review of behavioral interventions to promote intake of fruit and vegetables. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 111(10):1523-1535.

Varotto, A., and A. Spagnolli. 2017. Psychological strategies to promote household recycling: A systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions. Journal of Environmental Psychology 51:168-188.

van der Werf, P., J.A. Seabrook, and J.A. Gilliland. 2019. “Reduce food waste, save money”: Testing a novel intervention to reduce household food waste. Environment and Behavior. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/0(0):0013916519875180.

Webb, T.L., and P. Sheeran. 2006. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin 132(2):249-268.

Whitehair, K.J., C.W. Shanklin, and L.A. Brannon. 2013. Written messages improve edible food waste behaviors in a university dining facility. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 113(1):63-69.

Whitmarsh, L.E., P. Haggar, and M. Thomas. 2018. Waste reduction behaviors at home, at work, and on holiday: What influences behavioral consistency across contexts? Frontiers in Psychology 9:2447.

Williamson, S., L.G. Block, and P.A. Keller. 2016. Of waste and waists: The effect of plate material on food consumption and waste. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 1(1):147-160.

Young, W., S.V. Russell, C.A. Robinson, and R. Barkemeyer. 2017. Can social media be a tool for reducing consumers’ food waste? A behaviour change experiment by a UK retailer. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 117:195-203.

Young, C.W., S.V. Russell, C.A. Robinson, and P.K. Chintakayala. 2018. Sustainable retailing—influencing consumer behaviour on food waste. Business Strategy and the Environment 27(1):1-15.