2

Understanding Food Waste, Consumers, and the U.S. Food Environment

The context in which consumers waste food is complex. To understand the drivers of food waste behavior and possible ways to reduce it, it is important to understand the elements of the interconnected food system mentioned in Chapter 1. This chapter provides an overview of U.S. consumers’ proximal interactions with parts of the food system, including where and how they purchase food and what they know about food. The chapter also describes efforts already under way to address consumer food waste.

The committee notes that the COVID-19 pandemic, which developed as work on this report was being completed, has disrupted the food system and is affecting consumer behavior in numerous ways both large and small. As this report goes to press, the pandemic is still developing, and researchers have not yet had time to document all these changes and assess their impact, but doing so will undoubtedly be a vital contribution to the understanding of consumer food waste in the future.

THE U.S. CONSUMER WITHIN THE FOOD SYSTEM

U.S. consumers are diverse across virtually any dimension; gender, race, ethnicity, economic status, and cultural traditions are but a few examples. Their food practices, including the wasting of food, are influenced not only by individual and interpersonal factors, such as income, attitudes, knowledge, and relationships, but also by the complex, dynamic food system. The food system comprises a range of individuals, groups, organizations,

and industries whose actions (e.g., enacting policy, informing the public, selecting and marketing products) can influence consumer behavior and the likelihood of food waste. The system also encompasses cultural, social, and economic drivers that operate at the community, state, and federal levels (Contento, 2016). These elements are key to strategies that can change behavior and reduce food waste at the consumer level. A sampling of important stakeholders is listed in Box 2-1.

Consumers’ individual characteristics naturally have implications for their food waste behavior: people respond in varying ways to situations in which decisions about food are made. For example, Aschemann-Witzel and colleagues (2018) found that among those consumers who thought about food waste at the grocery store, the top reason for doing so was saving money, but many also considered the goal of reducing waste overall, environmental concerns, or the need to ensure food access for all. For others, avoiding food waste may have become a habit.

Researchers have suggested that consumers can be divided into five segments based on their food waste practices (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2018). In this categorization, one group likes cooking, considers price and taste important, but does not plan in advance, and reports a medium level of food waste. Another group is concerned with price but dislikes cooking;

this group reports low levels of food waste. A third group is very engaged in cooking, is concerned about price and taste, and plans in advance, and reports low levels of food waste. The fourth group does not consider price but is interested in taste, food safety, and optimal choice, and reports a medium level of food waste. Finally, the fifth group is not very involved with food and has a low level of interest in cooking, food safety, or the price–quality relationship; this group reports the highest level of food waste. The complexity of these segments illustrates that reducing food waste involves more than simply raising consumer awareness. For example, consumers with low levels of interest in food and food waste are not likely to be swayed by economic, normative, or ethical appeals designed to increase awareness but may respond best to structural interventions such as “nudges1” (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008).

An important question is how income level influences the wasting of food, although the available research on this question is not conclusive. For example, some studies have suggested that households with higher income waste more (e.g., Filipová et al., 2017; Soma, 2019; Verma et al., 2020), while other work suggests that households with low income may waste more of certain items, such as lower-quality foods purchased in bulk (Setti et al., 2016). Investigating questions about the role of income level in food waste is challenging, in part because many consumers with low income lack access to the digital connections researchers use for online data collection, and they, like other consumers, may also lack familiarity with ordinary survey instruments. Thus, reaching them to learn about their motivations and experiences is difficult. Researchers can turn to other methods, such as ethnographic analysis, to better understand how people, particularly those with low incomes, interact with food and food waste.

The relative expense of food is much higher for low-income than for higher-income consumers, even though the food available in their communities may be of lower quality and less varied. Also, the food available through government allocations, food banks, and charities is different in many ways from that available to more affluent consumers. These are just two of the ways food may have different meanings for consumers with low-incomes and higher-incomes, and reasons they may respond differently to interventions to reduce food waste. However, the existing research on food waste and equity focuses primarily on the role of donations to feed those who are food insecure, rather than on identifying drivers or long-term

___________________

1 A nudge is a modification of the way choices are presented (choice architecture) that influences behavior by such means as removing external barriers, expediting access, or altering the structure of the environment. In the context of food waste, a nudge might, for example, shift perception of the quantity of food (e.g., changing plate sizes); shift the appeal or quality of food (e.g., increasing the appeal of healthy foods); or make a behavior easier (e.g., offering healthy food in a cafeteria at the beginning of the line).

solutions related to improving equity or reducing food waste (Riches, 2011; Tarasuk and Eakin, 2005; Warshawsky, 2015).

The fact that low-income and more affluent consumers may respond to issues related to food waste differently suggests that they may need to be considered separately. However, multiple factors, including race, gender, and education level, intersect with poverty in ways that are important for food waste research, as for almost any social science research. The diverse motivations, contexts, and responses that influence all consumers call for a nuanced approach to research on both drivers of food waste behavior and interventions to change that behavior to take these differences into account. One way to do this is to apply the segmentation approaches used by food marketers to appeal to individual food preferences.

Where and How Consumers Buy Food

Researchers focus on how consumers behave in various settings to understand what may influence their decisions about food acquisition and consumption. Thus they examine how and where consumers interact with food they obtain from food retailers, charities and other sources of free food, or online, or in food service venues.

Food Retailers

Supermarkets and supercenters

Supermarkets and supercenters (hypermarkets) are the dominant sources of food for Americans, with pharmacies and dollar stores increasingly becoming sources as well (Caspi et al., 2017). Supermarkets are relatively scarce in rural and some urban areas and also on American Indian reservations, however (Bird Jernigan et al., 2018). African American neighborhoods at all poverty levels have 40–70 percent fewer chain supermarkets per census tract relative to high-income white neighborhoods; Hispanic neighborhoods have only 14–40 percent as many supermarkets as non-Hispanic neighborhoods (Bower et al., 2014); and many individuals living on American Indian reservations depend on convenience stores for groceries (Bird Jernigan et al., 2018).

Different marketing, food assortment, and store design approaches can result in more or less food waste at the consumer level. Several studies have found that modern supermarket and supercenter formats have a tendency to encourage consumers to overpurchase, resulting in more food waste, compared with traditional or smaller retail outlets (Lee, 2018; Soma, 2019). Overpurchasing can be stimulated by such features as retail loyalty programs that hold a significant amount of consumer data and offer nudges

(e.g., redeemable rewards designed to entice them to make more purchases) (Carolan, 2018). Globally, an estimated 1.5 billion people have registered for such programs (Carolan, 2018). Other reasons for overacquisition are the ubiquity of promotional and “buy one, get one free” offers, the availability of many varieties of food, and offers that encourage stocking up (Lee, 2018; Soma, 2019). Although prompts, cues, and nudge-like strategies often encourage increased acquisition, these strategies could be redesigned to encourage consumers to buy “smarter,” which could reduce food waste.

In addition to marketing strategies and the variety of foods offered, store design approaches, such as a store’s social dimensions or atmosphere, can encourage consumers to shop at a store (Baker et al., 2002). Attractive displays and a festive environment, for example, serve as cues to consumers to spend more time and buy more (Sneed, 2014).

Other Places to Acquire Food

In addition to conventional retail outlets, consumers have other options for purchasing food. For example, approximately 12 percent of American adults shop for food at farmers’ markets, a rate that is increasing (Dimitri and Effland, 2018). Consumers who frequent farmers’ markets are interested in more than food; they are also seeking social connections in the community, better connections with growers, sustainable foods, and ways to support the local economy (Zepeda, 2009).

Food cooperatives, which are user owned, user controlled, and focused on distributing benefits to their members, are another alternative to corporate or multinational retail outlets (Curl, 2012). According to Zitcer (2015), sales at these venues have tripled in the past 10 years. Community-supported agriculture (CSA), another outlet for acquiring food based on membership, offers a direct connection to farmers. The number of CSAs has increased significantly, rising from 1,700 in 2005 (Weise, 2005) to 7,398 in 2015, when CSAs contributed $226 million in direct farmer-to-consumer sales (USDA, 2016).

Charities, including food banks, soup kitchens, and food pantries,2 are part of the emergency food sector, serving the food insecure (more than 37 million people in the United States) (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2019). Food banks generally acquire their inventories through donations, government foods, and institutional purchases. Donations generally make up the greatest proportion of their inventories, and may include retail or farm surplus donations (Ross et al., 2013). One of the challenges associated with food bank donations is that they may not consist of culturally appropriate foods for their location, which may result in wasted food.

___________________

2 Food banks serve as warehouses and food pantries serve the community by distributing food from those warehouses.

Finally, a small group of Americans acquire food from dumpster diving, identifying themselves as “freegans.” Others, especially in rural or remote communities, rely on hunting, fishing, and farming or acquire much of their produce from gardening. According to Ganglbauer and colleagues (2013), the benefits of gardening with respect to reducing food waste include that the food is readily available when needed. In addition, the work of cultivating, harvesting, and preserving (e.g., freezing and canning) food gives consumers a greater connection to its production, which has been shown to increase its perceived value and to reduce waste (Ganglbauer et al., 2013).

New Models: Online-based Food Acquisition

Online grocery shopping for food that is delivered to the consumer’s doorstep or made available for store pickup is becoming increasingly popular. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was projected that 70 percent of U.S. shoppers could be purchasing their groceries online as early as 2022 (FMI and Nielsen, 2018). The pandemic may accelerate the use of online shopping (IFIC Foundation, 2019a), although there are many uncertainties regarding its trajectory and its effects on the food system.

In general, online grocery shoppers tend to make more repeat and frequent purchases, as well as to place larger orders, relative to traditional (nonfood) online shoppers (Yuan et al., 2016). Several features of online grocery shopping make these consumers a promising target for strategies to reduce food waste. For example, such nudges as “recommender systems” are core to online grocery shopping. Recommender systems expose consumers to new items that help them find complementary and relevant items quickly (Yuan et al., 2016). Like many emotional cues used by marketers, however, these systems can also lead to unreflective exploratory behaviors and impulse buying that increase the likelihood of food waste. Further, the combination of recommendations and low search costs can prompt consumers to purchase food that does not match their preferences (Diehl, 2005), as has been seen with other types of products. In addition, the greater variety available online may prompt consumers to have higher expectations about product quality, leading to subsequent disappointment and a greater propensity to discard relative to smaller offline assortments (Diehl and Poynor, 2010). Online shopping also has the potential to affect consumers’ psychological distance from food and its meaning.

Eating away from Home: The Influence of the Food Service Industry

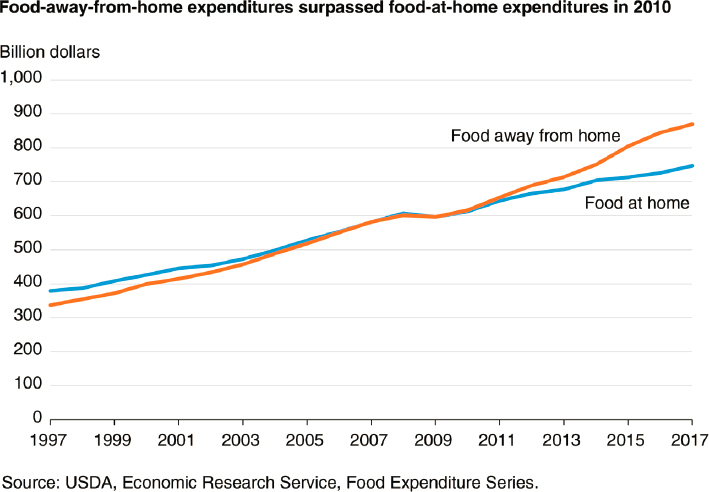

Before the COVID-19 pandemic made social distancing a health imperative, Americans were eating out more than ever before, with expenditures

on food away from home surpassing those on food at home in 2010 (Okrent et al., 2018) (Figure 2-1). As of this writing, the closing of food service venues during the pandemic to minimize transmission of the virus has forced consumers to eat at home more and likely affected other food-related practices. The pandemic, which has disrupted all levels of the food system, is novel and unprecedented, so projections about eating away from home or other food-related behaviors are not possible. Before these changes occurred, however, individuals aged 22–37 were the group most likely to eat away from home; exhibited a greater preference for convenience foods, including ready-to-eat foods; and spent less time and money preparing food at home. Even when they did eat at home, they were more likely to purchase prepared foods (Kuhns and Saksena, 2017).

In general, the popularity of eating away from home has resulted in a substantial increase in plate waste in U.S. restaurants over the past 30 years (Gunders, 2017). Although this is not a recent trend, academic research on drivers of consumer food waste has focused largely on drivers inside the home. The drivers operating at home and away from home are likely to differ significantly (see Chapter 3).

Educational institutions are particularly promising venues for reducing food waste, not only because they are places of learning where lifelong

SOURCE: USDA/ERS (Elitzak and Okrent, 2018).

habits are formed, but also because of the number of meals served. For example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Food and Nutrition Service, through the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program, serves more than 31 million children per day in approximately 100,000 schools in the United States (95 percent of all schools and residential care institutions). The National School Lunch Program is usually administered by state education agencies, which operate the program through agreements with school food authorities.

Changing Trends in Consumer Payment

Financial trends and economic structures influence consumer practices. The advent of modern payment systems, such as digital wallet payments, and the increasing number of retailers and restaurants discouraging cash-based payment or going completely cashless (Olson and Sweet, 2019) have resulted in increased consumer purchasing (Bourke et al., 2019). In a 2018 survey of 1,222 American consumers, 23 percent of respondents reported using credit cards at supermarkets, while 62 percent said they used debit cards and only 13 percent cash (TSYS, 2019). Research has shown two results of the use of cashless payment: decreased awareness of spending with the absence of the physical aspect of exchanging cash for a product and reduced attention to price cues (Greenacre and Akbar, 2019; Prelec and Simester, 2001). It is reasonable to consider whether the growing use of card-based digital payment also contributes to overpurchasing of food and food waste.

From a retail perspective, card-based payment can be combined with loyalty programs and tied to purchasing nudges (Carolan, 2018), such as reward points or discounts. For example, in a 2017 study of 1,200 consumers, 68 percent of American respondents cited vendors’ use of reward programs as the most attractive feature of paying by credit card, an increase from 55 percent in 2015 (TSYS, 2018). Some of the largest food retailers, including Target, Walmart, Costco, Amazon/Whole Foods, and Trader Joe’s, also offer reward points when consumers use the retailers’ own branded credit cards to make purchases at their stores. Accordingly, a better understanding of trends in the interaction among financial systems, consumer purchasing, and food consumption decisions is critical to understanding consumer practices related to food waste.

The Role of Technology

Broadly speaking, food processing (e.g., freezing, canning, packaging) can be defined as any intentional change to a food occurring between the point of origin and availability for consumption. For consumers, processing

of food can increase its safety, quality, convenience, and nutritional value. The application of food technology in the manufacturing sector allows foods to be processed in ways that directly influence how consumers buy, prepare, and store their food. In this way, food technology has a profound impact on the amount of wasted food: it directly contributes to longer shelf lives for foods and to the availability of single-serve portions and prepared meals that can result in less potential for waste.

A recent review examines technologies that can be implemented by the food manufacturing sector to decrease food waste at the consumer level, related to the design of the food itself, its processing, and its packaging (Tavill, 2020). For example, foods can be designed with formulas (e.g., preservatives) and processes (e.g., freeze-dried) that result in longer shelf lives. Food packaging, including the use of modified-atmosphere packaging, can also increase shelf life. Food waste can also be reduced by such features as dispensing caps and reclosable zippers that can reduce accidental spillage. Still other technologies may help consumers navigate lack of time and energy and the cognitive demands of everyday life. These technologies include apps and other devices (e.g., online gamification tools, smart grocery carts) to help consumers with food planning during the acquisition, preparation, and storage and increase their awareness of their own food waste levels. As researchers continue to explore the efficacy of these technologies in reducing food waste, it will be important to consider other issues as well, such as consumer acceptability and access, safety, environmental impacts, and equity impacts.

Consumers’ Food Literacy

Food literacy is a multidimensional concept that has been defined in many ways. For example, it has been defined from a nutrition and health perspective as referring to food-related knowledge, skills, and behaviors associated with “navigating the food system and using it in order to ensure a regular food intake that is consistent with nutrition recommendations” (Vidgen and Gallegos, 2014, p. 50). Others have characterized food literacy as encompassing such interconnected attributes as food and nutrition knowledge, food skills, self-efficacy, and confidence, as well as people’s food decisions and the influence of external factors (e.g., the food system, social determinants of health, sociocultural influences, and eating practices). For the purposes of this report, food literacy is defined as a set of knowledge and skills that help people with the daily preparation of healthy, tasty, affordable meals for themselves and their families. That is, it includes both conceptual knowledge about food and the skills needed to plan, acquire, prepare, and store food.

Aspects of food literacy most relevant to minimizing food waste are related to planning, preparing and cooking, and storing food. Food literacy has a significant influence on these behaviors because it is associated with a number of drivers of food waste at the consumer level (see Chapter 3). Because it is likely to be closely related to the root causes of food waste, its improvement should result in less food waste. For example, better knowledge about food safety and of improved methods for preparing and storing food allows people to maximize the life of their food. This section describes the most common sources of food and nutrition information in the United States. It also explains how some important knowledge gaps and misconceptions, particularly about food safety, are likely to relate to food waste at the consumer level.

Sources of Food and Nutrition Information

Food literacy varies greatly among consumers, partly because they acquire information about food through a variety of sources, settings, and personal experiences. Some aspects of food literacy (e.g., knowing what parts of a food are edible) relate to culture and social norms.

A frequent source of food and nutrition information is product marketing at the physical or online store. In these settings, consumers face a challenging communication environment, including symbols on packages and a multitude of messages, some based on big data and personalized. Further, the messages encountered differ depending on the setting. Thus, for example, people with access to farmers’ markets and full-size grocery stores with a wide array of fresh and prepared foods may receive different information about food than do people with access only to convenience stores (NASEM, 2016).

American consumers are also increasingly influenced by a growing industry centered on food-related television programming, celebrity chefs, and celebrities. For some consumers, this industry has facilitated a growing focus on the relationship between food and health and additional knowledge about food preparation and planning, while for others it has encouraged spending less time planning and preparing meals (e.g., the use of meal kits) (NASEM, 2016).

Government sources (e.g., the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA], USDA) offer information to increase consumers’ knowledge about a variety of food-related topics, such as the health benefits of fruits and vegetables and food safety. Additional guidance for consumers can come from mobile apps, such as FoodKeeper, developed by USDA to help maximize food freshness and quality through storage advice for specific foods; the FDA’s Nutrition Facts label; or books (Gunders, 2015; Hard, 2018; James Beard

Foundation, 2018; Lightner, 2018). In one study, consumers reported that they often rely on more than one source for food-related information, but put the most trust in registered dietitian nutritionists and health care professionals, followed by scientific studies, wellness and fitness professionals, and government agencies. Least trusted were food manufacturers and news articles. And younger adults were more trusting of technology-based sources compared with older Americans (IFIC Foundation, 2018). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has driven many consumers to place more trust in government agencies, scientific studies, health care professionals, and friends and family (IFIC Foundation, 2019b). Still, consumers are much less likely to be exposed to government and evidence-based messages than to those from the food industry or influencers.

Increasingly, food literacy is being taught in schools. In the years following World War II, home economics programs that included cooking skills slowly disappeared, but many U.S. schools have started developing food literacy-related curricula involving school gardens and cooking programs (Blair, 2009). University courses have also emerged as an opportunity to develop food literacy. With a focus on literacy about food waste, the Food Waste Warrior Toolkit3 was developed by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to provide lessons, activities, and resources informing children of different ages about the effect of food waste on the planet. For children, family members are a frequent source of information, but the reverse is also true: children can be a vehicle for improving food literacy in the family by introducing skills learned in school.

Consumers receive an immense volume and diversity of information about food through social and digital media and many other means. This information includes opinions, advice, and scientific information, and it can be contradictory, confusing consumers. American consumers need accurate and consistent information about how to plan, shop for, prepare, and store food, particularly at this pivotal moment as the food system’s supply chain continues to shift in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Myths about Food and Nutrition

A workshop held by the National Academies in 2016 addressed the growing gap between cultural interest in food and actual scientific food literacy, due in part to “pop culture nutrition noise” that has created a disconnect between science and food-related behaviors (NASEM, 2016, p. 23). A few misperceptions—or myths—about food quality, food safety, composting, and food production practices in particular influence food waste behaviors.

___________________

3 See https://www.worldwildlife.org/teaching-resources/toolkits/food-waste-warrior-toolkit.

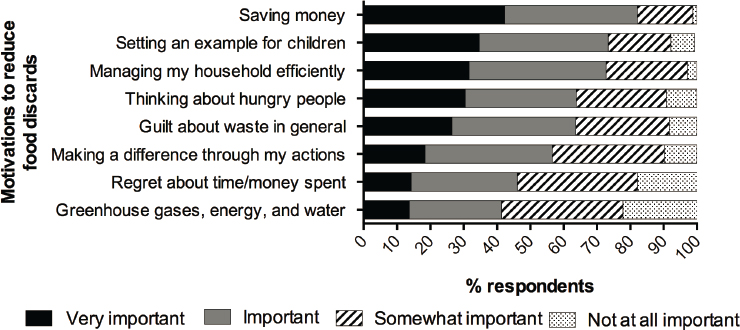

Awareness about Wasted Food

Neff and colleagues (2015) studied U.S. consumers’ awareness, attitudes, and behaviors related to food waste using an online survey. Forty-two percent of respondents had seen information about food waste. About 62 percent described themselves as “very” or “fairly” knowledgeable about the subject; 69 percent reported discarding 10 percent or less of their food and only 10 percent reported discarding 30 percent or more. When asked how much of their household’s food waste could be avoided, only 29 percent responded “a fair amount” or “a lot.” These results are at odds with current estimates of overall food waste at the consumer level, suggesting that consumers underreport their waste and that awareness of the problem could be improved. Worries about food poisoning and the desire to eat only the freshest food were the top reasons people cited for discarding food (see Figure 2-2), results that align with those of a 2019 survey that identified spoilage or staleness as the top reason foods end up in the garbage (83%) (IFIC Foundation, 2019a). That survey also revealed that among the motivations for reducing food discards, environmental concerns was last, highlighting the possible lack of knowledge in this area and an opportunity to intervene.

Food Safety and Quality

Although the CDC, FDA, and USDA all provide clear information regarding food preparation and safety, handling foods in a safe manner can be counterintuitive and a challenge in practice. For example, an FDA

NOTES: Percentages indicate the proportion of respondents who chose each response. Restricted to respondents reporting in a separate question that they compost at least some of their food; percentages for all other motivations reflect the entire sample.

SOURCE: Neff et al., 2015.

survey found that, despite their concerns about raw chicken (66%) and raw beef (41%) being contaminated, as many as 68 percent of consumers said they always washed raw chicken parts before cooking them, a practice not recommended by food safety experts because it increases the risk of cross-contamination of other foods and surfaces (FDA, 2016b). In another example, although proper food storage to maximize shelf life is the most common way consumers try to reduce wasted food (60%) (IFIC Foundation, 2019a), studies have shown that consumers are confused about the meaning of shelf-life labels (i.e., date labels) (see Box 2-2). In terms of food quality, the 2019 IFIC Food and Health Survey cited above showed that having trust in a brand, recognizing the product ingredients, and knowing where their food comes from are all highly important for consumers (IFIC Foundation, 2019b). In addition, as described in Box 2-2, consumers often judge the quality of a food by its appearance, which results in the wasting of high-quality food.

Environmental Sustainability

The 2019 IFIC Food and Health Survey found that while environmental sustainability was the lowest-rated of the purchase drivers included in the survey, 6 in 10 consumers said it was difficult to determine whether the food choices they made were environmentally sustainable, and 63 percent of those respondents said environmental sustainability would have a greater influence on their choices if this information was clearer (IFIC Foundation, 2019b). This lack of clarity is exemplified by two myths that may increase food waste: the perceptions that all packaging is bad for the environment and that composting is the best option for managing excess household food (Box 2-3).

Nutrition

The 2019 IFIC Food and Health Survey found that 60 percent of consumers had seen the MyPlate graphic, a USDA tool designed to communicate dietary information. However, only 1 in 4 consumers surveyed said they sought health benefits from food (IFIC Foundation, 2019b). It is encouraging that in the 2014 FDA Health and Diet Survey, 77 percent of U.S. adult respondents reported using the Nutrition Facts label when buying food products (FDA, 2016a). Nevertheless, consumers appear to be confused about the benefits and risks of food processing; the misperception that fresh products provide more essential nutrients relative to processed products is particularly pervasive (see Box 2-4). This perception likely results in higher amounts of food waste, as consumers may favor perishable foods over frozen or canned foods.

EFFORTS TO ADDRESS CONSUMER FOOD WASTE

The past decade has seen significant momentum to address food waste, in part because the publication of several seminal reports raised awareness of the substantial rates of waste across the food system (e.g., Gunders, 2017). Researchers and other stakeholders have not only communicated the magnitude of the problem but also sought approaches for addressing it.

The problem has generated great interest among the food industry (e.g., the Food Waste Reduction Alliance [FWRA]); environmental organizations (e.g., the Natural Resources Defense Council, WWF, the World Resources Institute); food justice groups (e.g., Feeding America); and others. Each of these groups has different goals, including increasing food production efficiencies, decreasing greenhouse gas emissions, improving resource efficiencies, and ensuring food security in communities. Groups focused exclusively on the mission of reducing food waste have produced important reports to raise awareness and provide roadmaps and practical solutions (e.g., ReFED in the United States, the Waste and Resources Action Programme in the United Kingdom). Many organizations have developed guidelines to help institutions and consumers reduce food waste (see Table C-2 in Appendix C).

The 2015 United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development specifically addressed food waste, calling for a 50 percent per capita reduction in wasted food at the retail and consumer levels and a reduction in food

losses along the supply chain by 2030 (United Nations, 2020). According to projections, those reductions would have vast effects on food security, land available for agriculture, and greenhouse gas emissions (Searchinger et al., 2018; Springmann et al., 2018). Another noteworthy international initiative is Champions 12.3, a coalition of leaders from government, business, international organizations, research institutions, farmer groups, and civil society dedicated to “inspiring ambition, mobilizing action, and accelerating progress toward achieving SDG [Sustainable Development Goals] Target 12.3 by 2030.”4 This group convenes to assess progress, share experiences in overcoming barriers and success stories, and identify opportunities. Many other governmental and nongovernmental initiatives in countries around the world are contributing to the momentum.

U.S. Government Initiatives

In addition to their individual activities related to food waste (e.g., educational material on date labels, support for research), relevant U.S. federal agencies have engaged in interagency collaborations to address the problem. In 2015, EPA and USDA called for a first national goal of a 50 percent reduction in food loss and waste by 2030, which stimulated great motivation to act among businesses and organizations. Of note is the creation of the Food Loss and Waste 2030 Champions voluntary program, which features businesses and organizations that have committed to reducing food loss and waste in their own operations in the United States by 50 percent by 2030 (see examples of their work in Table C-3 in Appendix C).

Federal government efforts resulted in the announcement of the 2019 U.S. interagency (EPA, USDA, and FDA) Winning on Reducing Food Waste Initiative, which recently published a strategic plan (EPA, 2019).5 In Congress, changes to federal policy are being considered, such as the Food Date Labeling Act, which would standardize the language on date labels at the national level so consumers would better understand their meaning. Other proposed federal legislation, the School Food Recovery Act, would provide resources for schools to implement food waste education programs.

Motivated by the 2030 goal, many state and local governments have adopted policies and plans for reducing the amount of food that is wasted in their jurisdictions (Gorski et al., 2017). Many of these efforts have focused on recycling wasted food by encouraging composting and instituting landfill bans. As many as one-fourth of communities in the United States have implemented unit-based pricing policies whereby residents pay for

___________________

4 See https://champions123.org/about/.

5 See https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/winning-reducing-food-waste-federalinteragency-strategy.

the removal of municipal solid waste per unit of waste collected rather than through a fixed fee or property taxes (EPA, 2016). These policies have been successful at reducing food waste (see also Chapter 4). Although not directly intended for source reduction, policies that ban the disposal of organic materials in landfills, introduced in six states and seven municipalities as of 2019 (Sandson and Broad Leib, 2019), may help reduce food waste. These initiatives and programs are relatively new and have not been in place long enough for their effects on reducing the amount of wasted food in the United States to be evaluated (see Box C-1 in Appendix C for some examples).

U.S. Food Industry Efforts

Like consumers, the U.S. food industry is diverse across many dimensions, including culture and philosophy. At many companies, however, reducing food waste is viewed as the right thing to do and as a component of an overall sustainability strategy. For example, advancing packaging and processing technologies to make food last longer has long been a priority in the manufacturing sector. Although originally designed to improve safety, convenience, and quality, these technologies are now at the core of reducing food waste throughout the food system, including at the consumer level. Numerous manufacturers are working to improve these technologies and their acceptability to consumers.

The retail and food service industries interact with consumers in varied and complex ways. These businesses have direct relationships with consumers and seek to earn and retain their trust, loyalty, and patronage. They also have reason to prompt consumers to purchase more and different foods, and they use their understanding of consumers’ motivations related to acquiring food, as well as marketing tactics, to influence consumers’ purchases.

Although retaining consumers and selling more food are sensible goals for businesses, many of the tactics they use may have unintended consequences, including unnecessary food waste by consumers. For example, larger serving sizes are particularly appealing to value-oriented consumers, regardless of the potential for excess food to be wasted. The fear of losing customers may discourage many businesses, particularly restaurants, from offering smaller serving sizes. In the retail sector, such strategies as nonlinear pricing schemes that promote the purchase of larger sizes have been used as a means of nudging consumers toward choices that yield greater profit (Dobson and Gerstner, 2010). Further, food delivery services, which have become even more popular during the COVID-19 pandemic, have virtually no incentive to encourage consumers to eat already-purchased foods, since this waste-reducing behavior might compromise their growth.

Nevertheless, most companies in the food industry (manufacturers, retailers, and food service venues) recognize the importance of reducing food waste within their own operations. Empirical data show that food businesses can reap economic benefits from investing in approaches to reduce food waste (Hanson and Mitchell, 2017). It may be counterintuitive, however, for businesses to strive to help consumers waste less food if they believe doing so might decrease appeal to customers and profits. Moreover, leaders might not be aware of the important nonfinancial reasons for reducing food loss and waste, related to food security, environmental sustainability, stakeholder relationships, and a sense of ethical responsibility.

There are opportunities for the food industry to promote consumer behaviors that result in reductions in food waste while maintaining economic sustainability. The adoption of voluntary environmental programs (e.g., Carbon Disclosure Project, Global Reporting Initiative, Leadership in Engineering and Environmental Design, International Standard for Organization [ISO] 14001, or the Certified Green Restaurant standard) that are administered by third-party organizations can bring increased customer loyalty (Borck and Coglianese, 2009). Being able to communicate credibly that they are taking action to support waste reduction or other beneficial goals (e.g., pollution control) may make companies more attractive to potential consumers. Despite their effectiveness,6 however, these certification programs are largely silent on specific actions businesses can take to decrease waste that might be generated by their consumers as a consequence of their operations. Even in the case of the Certified Green Restaurant standard, only two of the hundreds of qualifying practices support reducing waste created by consumers (e.g., offering smaller reduced-price versions for at least half of all entrees or offering bread only upon request).

Three sectors of the food industry—manufacturers, retailers, and restaurants—have collaborated on efforts to reduce food waste in their operations through the FWRA, which was initiated in 2011 and focused initially on assessing food waste and associated practices. Recently, the FWRA entered a formal agreement with USDA, EPA, and FDA to support the interagency Winning on Reducing Food Waste Initiative.

Thus far, most industry efforts have focused on businesses’ operations, with less attention to decreasing consumer food waste. However, some individual companies have already publicly committed to increasing their efforts to reduce food waste, for example, by offering trayless dining

___________________

6 ISO 14001, for example, is a standardized environmental management system (EMS) that has been implemented by more than 300,000 organizations globally. An EMS helps organizations develop a holistic approach to identifying, managing, monitoring, and controlling aspects of operations that can affect the natural environment. Firms that have adopted the ISO 14001 EMS may be certified by third-party certifiers who can then credibly communicate firm adoption and adherence. For evidence of the effectiveness of ISO 14001, see Boiral et al. (2018).

or smaller portion sizes (see Table C-3 in Appendix C for additional examples). In addition, the Consumer Brands Association (formerly known as the Grocery Manufacturers Association) and FMI-The Food Industry Association (formerly the Food Marketing Institute) have collaborated to develop a set of voluntary standards for date labeling to help consumers make better decisions about acquiring and utilizing food, which could result in less disposal of wholesome food. An example of a relevant initiative is guidance developed in the United Kingdom for retailers on how to develop food promotions that will not contribute to increased food waste.7

At the regional level, such initiatives as the West Coast Voluntary Agreement to Reduce Wasted Food,8 which recently called for the engagement of food retailers and their supply chain partners to reduce and prevent food waste by 50 percent by 2030, show promise. At the global level, the Consumers Goods Forum,9 a global association of 400 companies representing $2.7 trillion in combined annual sales, has committed to halving food waste by 2025.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

A systems approach to reducing consumer food waste is premised on the fact that consumers are embedded within multiple systems (natural, economic, political, and technological) and that positively influencing consumer practices requires an understanding of interactions within these systems. Therefore, addressing the problem requires moving beyond consumers and examining the myriad influences on their food waste behaviors within the larger food system. This chapter serves as the foundation for the discussion in Chapter 3 of the drivers of consumer behavior that have been identified in the scientific literature, which operate at the individual, intrapersonal, and interpersonal levels, as well as the broader, societal level.

CONCLUSION 2-1: Consumers’ decisions about food are influenced by such individual factors as income, attitudes, and knowledge. Consumers are also embedded within a food system that includes natural, economic, political, social, and technological contexts. The drivers of consumer food waste need to be understood in the context of interactions within the food system, including the manufacturing, retail, and food service sectors, as well as food-related media and advertising.

___________________

7 See https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food%20Promotions-%20Guidance%20for%20Retailers.pdf.

CONCLUSION 2-2: Consumers’ knowledge and attitudes with respect to food safety and quality, nutrition, and food waste are influenced by norms and culture, as well as information from many sources, including government, marketing, social media, public campaigns, and other sources that are not always accurate and evidence-based or culturally appropriate. Addressing consumers’ misconceptions about food is a promising goal for any effort to reduce food waste.

CONCLUSION 2-3: Individual companies, government entities, industry and public–private partnerships, and nonprofit organizations have undertaken significant efforts to reduce food waste, but few of these efforts have targeted consumer-level food waste, and the efforts have not been coordinated or systematically evaluated.

CONCLUSION 2-4: The food industry, including retailers, food service providers, and manufacturers, has a substantial influence on consumers’ decisions about food, which can be used to reduce food waste at the consumer level. Identifying business and marketing practices that can serve customers and generate profits while also discouraging food waste is a promising goal for food waste reduction efforts.

REFERENCES

AMERIPEN. 2018. Quantifying the value of packaging as a strategy to reduce food waste in America. Available: https://www.ameripen.org/general/custom.asp?page=foodwastereport.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., I.E. de Hooge, V.L. Almli, and M. Oostindjer. 2018. Fine-tuning the fight against food waste. Journal of Macromarketing 38(2):168-184.

Baker, J., A. Parasuraman, D. Grewal, and G.B. Voss. 2002. The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. Journal of Marketing 66(2):120-141.

Bird Jernigan, V.B., A.L. Salvatore, M. Williams, M. Wetherill, T. Taniguchi, T. Jacob, T. Cannady, M. Grammar, J. Standridge, J. Fox, J. Tingle Owens, J. Spiegel, C. Love, T. Teague, and C. Noonan. 2018. A healthy retail intervention in Native American convenience stores: The Thrive community-based participatory research study. American Journal of Public Health e1-e8.

Blair, D. 2009. The child in the garden: An evaluative review of the benefits of school gardening. Journal of Environmental Education 40(2):15-38.

Boiral, O., L. Guillaumie, I. Heras-Saizarbitoria, and C.V. Tayo Tene. 2018. Adoption and outcomes of ISO 14001: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews 20(2):411-432.

Borck, J.C., and C. Coglianese. 2009. Voluntary environmental programs: Assessing their effectiveness. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34(1):305-324.

Bourke, N., T. Roche, and R. Siegel. 2019. Rise of cashless retailers problematic for some consumers. Cash remains important payment option for many. Available: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2019/11/08/rise-of-cashless-retailers-problematic-for-some-consumers.

Bower, K.M., R.J. Thorpe, Jr., C. Rohde, and D.J. Gaskin. 2014. The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Preventive Medicine 58:33-39.

Broad Leib, E., C. Rice, R. Neff, M. Spiker, A. Schklair, and S. Greenberg. 2016. Consumer perceptions of date labels: National survey. Available: http://www.chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Consumer-Perceptions-on-Date-Labels_May-2016.pdf.

Carolan, M. 2018. Big data and food retail: Nudging out citizens by creating dependent consumers. Geoforum 90:142-150.

Caspi, C.E., K. Lenk, J.E. Pelletier, T.L. Barnes, L. Harnack, D.J. Erickson, and M.N. Laska. 2017. Association between store food environment and customer purchases in small grocery stores, gas-marts, pharmacies and dollar stores. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14(1):76.

Coleman-Jensen, A., M.P. Rabbitt, C.A. Gregory, and A. Singh. 2019. Household food security in the United States in 2018, ERR-270. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Contento, I.R. 2016. Determinants of food choice and dietary change: Implications for nutrition education. In Nutrition education. Linking research, theory, and practice. Third ed., edited by I.R. Contento. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. Pp. 30-58.

Curl, J. 2012. For all the people: Uncovering the hidden history of cooperation, cooperative movements, and communalism in America. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Diehl, K. 2005. When two rights make a wrong: Searching too much in ordered environments. Journal of Marketing Research 42(3):313-322.

Diehl, K., and C. Poynor. 2010. Great expectations?! Assortment size, expectations, and satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research 47(2):312-322.

Dimitri, C., and A. Effland. 2018. From farming to food systems: The evolution of US agricultural production and policy into the 21st century. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 1-16.

Dion, K., E. Berscheid, and E. Walster. 1972. What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 24(3):285-290.

Dobson, P.W., and E. Gerstner. 2010. For a few cents more: Why supersize unhealthy food? Marketing Science 29(4):770-778.

Eagly, A.H., R.D. Ashmore, M.G. Makhijani, and L.C. Longo. 1991. What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin 110(1):109-128.

Elitzak, H., and A. Okrent. 2018. New U.S. food expenditure estimates find food-away-from-home spending is higher than previous estimates. Amber Waves. Available: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2018/november/new-us-food-expenditure-estimates-find-food-away-from-home-spending-is-higher-than-previous-estimates.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2016. Communities. 2006 PAYT programs. Available: https://archive.epa.gov/wastes/conserve/tools/payt/web/html/06comm.html.

EPA. 2019. Winning on Reducing Food Waste. FY 2019-2020 federal interagency strategy. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/winning-reducing-foodwaste-fy-2019-2020-federal-interagency-strategy.

EPA. 2020. Sustainable management of food. Reducing the impact of wasted food by feeding the soil and composting. Available: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/reducing-impact-wasted-food-feeding-soil-and-composting.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2016a. 2014 health and diet survey. Available: https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-releases-2014-healthand-diet-survey-findings.

FDA. 2016b. 2016 FDA food safety survey. Available: https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsanconsumer-behavior-research/2016-food-safety-survey-report.

Filipová, A., V. Mokrejšová, Z. Šulc, and J. Zeman. 2017. Characteristics of food-wasting consumers in the Czech Republic. International Journal of Consumer Studies 41(6):714-722.

FMI (Food Marketing Institute) and Nielsen. 2018. The digitally engaged food shopper. Available: https://www.fmi.org/newsroom/latest-news/view/2018/01/29/fmi-and-nielsen-report-70-of-consumers-will-be-grocery-shopping-online-by-2024.

Ganglbauer, E., G. Fitzpatrick, and R. Comber. 2013. Negotiating food waste: Using a practice lens to inform design. ACM Trans Computer-Human Interact 20(2):Article 11.

Gorski, I., S. Siddiqi, and R. Neff. 2017. Governmental plans to address waste of food. Available: https://clf.jhsph.edu/sites/default/files/2019-01/governmental-plans-to-address-waste-of-food.pdf.

Greenacre, L., and S. Akbar. 2019. The impact of payment method on shopping behaviour among low income consumers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 47:87-93.

Grewal, L., J. Hmurovic, C. Lamberton, and R.W. Reczek. 2018. The self-perception connection: Why consumers devalue unattractive produce. Journal of Marketing 83(1):89-107.

Gunders, D. 2015. Waste-free kitchen handbook: A guide to eating well and saving money by wasting less food. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

Gunders, D. 2017. Wasted: How America is losing up to 40 percent of its food from farm to fork to landfill. New York: Natural Resources Defense Council.

Hanson, C., and P. Mitchell. 2017. The business case for reducing food loss and waste. Washington, DC: Champions 12.3.

Hard, L.-J. 2018. Cooking with scraps: Turn your peels, cores, rinds, and stems into delicious meals. New York: Workman Publishing Company, Inc.

IFIC (International Food Information Council) Foundation. 2018. 2018 food and health survey. Available: https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018-FHS-Report-FINAL.pdf.

IFIC Foundation. 2019a. A survey of consumer behaviors and perceptions of food waste. Available: https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/IFIC-EPAL-Food-Waste-Deck-Final-9.16.19.pdf.

IFIC Foundation. 2019b. 2019 food and health survey. Available: https://foodinsight.org/2019-food-and-health-survey.

James Beard Foundation. 2018. Waste not: How to get the most from your food. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Kuhns, R., and M. Saksena. 2017. Food purchase decisions of millennial households compared to other generations, EIB-186. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Lee, K.C.L. 2018. Grocery shopping, food waste, and the retail landscape of cities: The case of Seoul. Journal of Cleaner Production 20(172):325-334.

Lightner, J. 2018. Scraps, peels, and stems: Recipes and tips for rethinking food waste at home. Seattle, WA: Skipstone.

Miller, S.R., and W.A. Knudson. 2014. Nutrition and cost comparisons of select canned, frozen, and fresh fruits and vegetables. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 8(6):430-437.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Food literacy: How do communications and marketing impact consumer knowledge, skills, and behavior? Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Neff, R.A., M.L. Spiker, and P.L. Truant. 2015. Wasted food: U.S. Consumers’ reported awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. PLoS ONE 10(6).

Okrent, A., E. Howard, T. Park, and S. Rehkamp. 2018. Measuring the value of the U.S. Food system: Revisions to the food expenditure series, TB-1948. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Olson, A., and K. Sweet. 2019. As cashless stores grow, so does the backlash. Available: https://business.financialpost.com/pmn/business-pmn/as-cashless-stores-grow-so-does-the-backlash.

Prelec, D., and D. Simester. 2001. Always leave home without it: A further investigation of the credit-card effect on willingness to pay. Marketing Letters 12(1):5-12.

Raghubir, P., and E.A. Greenleaf. 2006. Ratios in proportion: What should the shape of the package be? Journal of Marketing 70(2):95-107.

ReFED (Rethink Food Waste Through Economics and Data). 2016. A roadmap to reduce U.S. food waste by 20 percent. Available: https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf.

Riches, G. 2011. Thinking and acting outside the charitable food box: Hunger and the right to food in rich societies. Development in Practice 21(4/5):768-775.

Ross, M., E.C. Campbell, and K.L. Webb. 2013. Recent trends in the nutritional quality of food banks’ food and beverage inventory: Case studies of six California food banks. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 8(3):294-309.

Sandson, K., and E. Broad Leib. 2019. Bans and beyond: Designing and implementing organic waste bans and mandatory organics recycling laws. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic; Center for EcoTechnology.

Searchinger, T., S. Wirsenius, T. Beringer, and P. Dumas. 2018. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 564(7735):249-253.

Setti, M., L. Falasconi, A. Segrè, I. Cusano, and M. Vittuari. 2016. Italian consumers’ income and food waste behavior. British Food Journal 118(7):1731-1746.

Sneed, C.T. 2014. Local food purchasing in the farmers’ market channel: Value-attitude behavior theory. Available: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3168.

Soma, T. 2019. Space to waste: The influence of income and retail choice on household food consumption and food waste in Indonesia. International Planning Studies. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1626222.

Springmann, M., M. Clark, D. Mason-D’Croz, K. Wiebe, B.L. Bodirsky, L. Lassaletta, W. de Vries, S.J. Vermeulen, M. Herrero, K.M. Carlson, M. Jonell, M. Troell, F. DeClerck, L.J. Gordon, R. Zurayk, P. Scarborough, M. Rayner, B. Loken, J. Fanzo, H.C.J. Godfray, D. Tilman, J. Rockstrom, and W. Willett. 2018. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 562(7728):519-525.

Tarasuk, V., and J.M. Eakin. 2005. Food assistance through “surplus” food: Insights from an ethnographic study of food bank work. Agriculture and Human Values 22(2):177-186.

Tavill, G. 2020. Industry challenges and approaches to food waste. Physiology and Behavior 223:112993.

Thaler, R.H., and C.R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Townsend, C., and S.B. Shu. 2010. When and how aesthetics influences financial decisions. Journal of Consumer Psychology 20(4):452-458.

TSYS. 2018. 2017 U.S. consumer payment study. Available: https://www.tsys.com/Assets/TSYS/downloads/rs_2017-us-consumer-payment-study.pdf.

TSYS. 2019. 2018 U.S. consumer payment study. Available: https://www.tsys.com/Assets/TSYS/downloads/rs_2018-us-consumer-payment-study.pdf.

United Nations. 2020. Sustainable development goals. Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. Available: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2016. Direct farm sales of food: Results from the 2015 local food marketing practices survey. Available: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Highlights/2016/LocalFoodsMarketingPractices_Highlights.pdf.

Verma, M., L. de Vreede, T. Achterbosch, and M.M. Rutten. 2020. Consumers discard a lot more food than widely believed: Estimates of global food waste using an energy gap approach and affluence elasticity of food waste. PLoS ONE 15(2):e0228369.

Vidgen, H.A., and D. Gallegos. 2014. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 76:50-59.

Warshawsky, D.N. 2015. The devolution of urban food waste governance: Case study of food rescue in Los Angeles. Cities 49:26-34.

Weise, E. 2005. Support from city folk takes root on the farm. USA Today, May 12.

Yuan, M., Y. Pavlidis, M. Jain, and K. Caster. 2016. Walmart online grocery personalization: Behavioral insights and basket recommendations. In International conference on conceptual modeling. Springer, Cham. Pp. 49-64.

Zepeda, L. 2009. Which little piggy goes to market? Characteristics of US farmers’ market shoppers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33(3):250-257.

Zitcer, A. 2015. Food co-ops and the paradox of exclusivity. Antipode 47(3):812-828.

This page intentionally left blank.