3

Drivers of Food Waste at the Consumer Level and Implications for Intervention Design

The reasons that consumers waste food are diverse and complex, but understanding them is critical to identifying effective ways to reduce food waste. As in many behavioral domains, consumers’ actions in this area are driven by cultural, personal, political, geographic, biological, and economic factors that influence conscious and unconscious decisions. Researchers refer to the influences from all of these factors as the “drivers” of individual consumer behavior (see Chapter 1). Clearly, these factors are not always within the individual’s control. This report uses “drivers” as a general term that encompasses causal factors; factors that may be statistically correlated; and “intervening factors,” sometimes termed “mediators” or “moderators” that help explain causal pathways. In addition, drivers can include both the presence of factors that tend to promote a given behavior, such as, in the case of food waste, large portion sizes offered at restaurants, and the absence of factors that discourage a behavior, such as lack of knowledge of the negative consequences of an action.

Researchers from diverse disciplines, including psychology, economics, public health, and sociology, have made contributions to understanding the drivers of consumer behaviors, and identified numerous links between particular influences and actions, as discussed in Chapter 1. To make actionable recommendations for food waste reduction strategies as directed by the study charge (Box 1-1 in Chapter 1), the committee first sought evidence about the drivers of consumer behavior from research in six related fields: energy conservation, recycling, water conservation, waste prevention, diet change, and weight management. Conclusions from this work allowed us

to note lessons learned in other domains that may be applicable to future food waste research and intervention design.

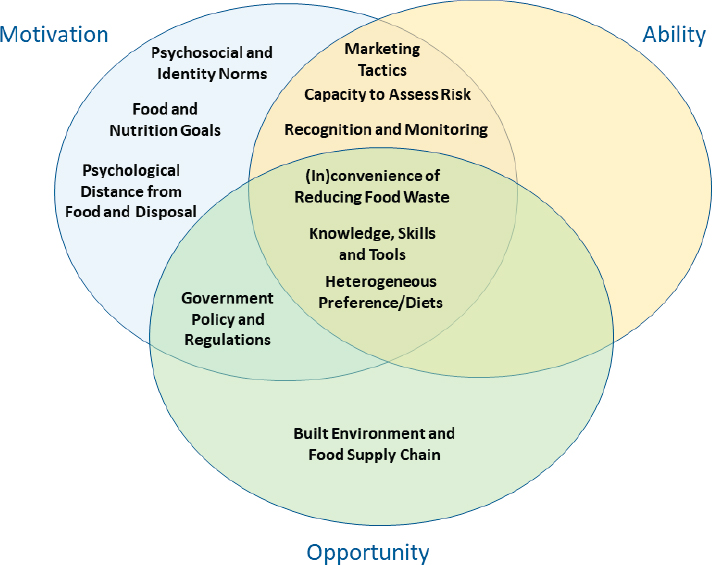

The committee then turned to identifying drivers specific to food waste both at and away from home. We identified 160 specific drivers supported by the literature, which we then clustered into 11 categories—types of drivers that may realistically be modified. This process allowed us to examine the characteristics of those drivers best supported by the literature, in terms of both the mechanism by which they operate (motivation, opportunity, and/or ability; see Chapter 1 and Appendix E) and the contexts in which they operate (at or away from home; related to food acquisition, consumption, or disposal). The chapter closes with the committee’s conclusions about drivers particularly likely to be useful in the design of interventions to reduce consumer food waste.

UNDERSTANDING DRIVERS OF BEHAVIOR IN OTHER DOMAINS

The committee conducted literature searches across the six related domains, focusing on systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These searches, conducted in ProQuest Research Library, PubMed, and Scopus, yielded a total of 406 reviews; the search process and method for analyzing the results are described in Appendix B. Some selected original studies with relevant insights were also reviewed. This section presents the committee’s insights about the drivers of consumer behavior at or away from home with potential relevance for wasted food and a few general observations.

Motivation, Opportunity, and Ability Work Together to Drive Behavior

Chapter 1 details reasons why the motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) framework provides a valuable approach for analyzing drivers of food waste behavior and considering interventions to change that behavior. This first section highlights empirical evidence that supports the validity of this framework. In the context of water conservation, for example, households were found to be more likely to adopt desired behaviors when they felt capable, were motivated, and had the opportunity to participate in the targeted behavior (Addo et al., 2018; Geiger et al., 2019). A meta-analysis of the causal mechanisms of water conservation behavior showed that opportunity was a moderate predictor of behavior, followed by motivation and then ability; the three together explained 37 percent of the variance in household behavior (Addo et al., 2018). This evidence reinforces the idea that combinations of drivers that address motivation, opportunity, and

ability should be considered jointly in both understanding behavior and designing potential interventions.

Sociodemographic Variables Are Often Insufficient or Poor Predictors of Behavior

Sociodemographic factors may alter consumers’ motivation, opportunity, or ability to behave in certain ways, and thus might appear to be important drivers to consider in the food waste and other domains. However, significant cultural variation at every socioeconomic level results in a wide range of routines, norms, and beliefs related to food. Further, some demographic characteristics are relatively fixed, while others can change. Often, therefore, these factors can obscure more than they clarify, and meaningful inferences will be based on examination of specific relationships among factors.

Research findings on the extent to which sociodemographic factors predict proenvironmental behavior are mixed. While some studies show correlation between specific behaviors and sociodemographic variables (e.g., Addo et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2010; Whitmarsh et al., 2018), others show different results, such as that sociodemographic variables have no significant influence on proenvironmental behavior (Li et al., 2019); that only income predicts recycling behavior (Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013); or that while well-educated people are generally more committed to resource conservation, they actually consume more (Koop et al., 2019).

Although there are trends in how sociodemographic variables may be associated with behaviors, many studies indicate that these variables contribute little to understanding of proenvironmental behavior and that psychological factors are more successful in predicting behavior and behavior change (Li et al., 2019). One meta-analysis suggests that, according to the studies examined, there was no need to tailor recycling interventions to different groups, in particular to households, students, or employees, because similar factors appeared to underlie the behavior of all of these groups (Geiger et al., 2019). Other studies within the six domains have illustrated that as a behavior (e.g., recycling) becomes habit, sociodemographic variables may no longer predict or significantly influence behavior (Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013; Soderhorn, 2010).

These nuanced findings suggest a need for careful attention to the strength of evidence about the roles of the different sociodemographic factors in the food waste literature, as well as consideration of whether any observed associations are causal or reflect the fact that demographics sometimes serve as partial proxies for other, more relevant factors. In the

food waste domain, the effect of sociodemographic factors has not been studied in depth. (A few inconclusive studies are mentioned in Chapter 2.)

Some Motivational Factors Are More Effective Drivers of Behavior than Others

It is tempting to think that simply having enough information about a given behavior or its impacts will change individuals’ choices. However, research in the six related domains shows that knowledge or information alone is insufficient as a predictor of people’s ability (i.e., knowledge for action) to change and maintain behavior (Abrahamse and Steg, 2013). By contrast, motivational factors, such as altered attitudes toward outcomes, values, agency, or perceived control, and social norms have been found to be more effective drivers of behavior (Li et al., 2019; Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013; Samdal et al., 2017). This is particularly true when consumers have baseline knowledge or can readily obtain it, with sufficient motivation.

Further, not all motivational factors are egocentric: several meta-analyses illustrate that proenvironmental behavior is driven more by normative (and sometimes environmental) concerns than by individual costs and benefits (Geiger et al., 2019; Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013). Similarly, environmental attitudes and beliefs, concerns about the future, and an individual’s sense of responsibility—all of which can shape motivation—may be more important drivers of proenvironmental behavior relative to sociodemographic variables (Li et al., 2019).

Norms play a particularly important role in behavior change. Moral norms (i.e., when people feel that doing something aligns with an abstract right or wrong); injunctive social norms (i.e., what one ought to do); and descriptive social norms (i.e., perceptions of what most people are doing) have increased in many societies and are strongly correlated with behavior (Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013; Whitmarsh et al., 2018). Moreover, activities that are presented as useful, pleasant, important, and widely accepted are more likely to be adopted and sustained than those that are viewed as someone else’s responsibility or inconvenient, or those that require a high bar of self-efficacy or locus of control (Cox et al., 2010; Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013). One caveat to this finding with relevance to food waste is that it may not always apply to prevention behaviors that are unseen (e.g., changing acquisition behaviors to purchase less in the first place). When an action is not visible—as is frequently the case for those actions categorized as prevention—social norms are unlikely to develop (Cox et al., 2010). Thus, one cannot assume that social norms drive food waste in the same

way—or should be managed in the same way—as they might in other behavioral contexts.

Contextual Factors1 Influence, and May Override, Other Drivers

A variety of evidence highlights the important influence of contextual factors and barriers on behavior in the six related domains. Several meta-analyses of household recycling interventions found that although researchers seldom considered such contextual factors as availability of curbside or convenient recycling, a bin at home, or space to store recycling before pickup (Geiger et al., 2019; Varotto and Spagnolli, 2017), they were strong predictors of waste reduction and recycling behavior (Geiger et al., 2019; Whitmarsh et al., 2018). A review of the literature on water conservation behavior found that water pricing was the most important variable explaining differences in domestic consumption in 10 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (Koop et al., 2019). Other studies suggest that psychosocial factors, such as attitudes and norms, are insufficient for overriding structural barriers to behavior (Karlin et al., 2015).

Despite the evidence regarding the importance of context, different motivations and barriers operate in different contexts, and people’s actions are therefore inconsistent across different times and places (Nash et al., 2017; Verplanken, 2018; Whitmarsh et al., 2018). Similarly, the effects of behavioral drivers may differ over time, both societally and individually, so drivers of food waste should not be considered static across time and contexts. Also, little is known about how drivers may differ at different phases in the behavior change process (Samdal et al., 2017). These findings illustrate that contextual factors vary and that those that change opportunity (e.g., marketing tactics, technology, the built environment, policies) at the food acquisition, consumption, storage, and disposal stages are similarly likely to affect food waste-related behaviors, independent of motivation or ability. Based on the number of and wide variation in contextual factors included among the summative drivers identified by the committee (see below), their importance and interactions with other drivers will need to be assessed for each population and setting.

___________________

1 Contextual factors are characteristics unique to a particular group, community, society, or individual. These factors include, but are not limited to, personal, social, cultural, economic, and political factors that exist in differing ways and have varying impacts across population groups.

Drivers Related to Habits2 Play a Key Role in the Way Behaviors Are Initiated, Sustained, or Disrupted

Habits are automatic once created. Although research on habits has implications for food waste, it is important to note that habits (e.g., avoiding the frozen foods areas of a retail store or remaining unaware of wasted food) vary in terms of their costs (e.g., in effort and time) and benefits (e.g., financial, health-related), so each specific habit needs to be examined individually. Nevertheless, there are valuable lessons with respect to habits for efforts to reduce food waste.

Multiple drivers may influence both the breaking of old habits and the establishment and maintenance of new ones, and it is therefore important to consider those drivers both separately and jointly. Drivers that operate through reflective mechanisms—that is, conscious cognitive processes—have received more research attention than have habits. However, there is evidence that the two have different effects; for example, established habits are not easily influenced by values and norms, and they predict and sustain behaviors because they are automatic (Cox et al., 2010; Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013; Whitmarsh et al., 2018) (see Chapter 1 for a discussion of reflective versus more automatic behaviors). Behavioral interventions aimed at altering habits have been less effective than interventions aimed at influencing single-action behaviors (e.g., buying an energy-efficient appliance) (Nisa et al., 2019). At the same time, interventions that have been successful in creating a new habit reveal that automatized behaviors are easier to sustain (Nisa et al., 2019).

There is reason to believe that drivers that prompt people to adopt new behaviors are different from those that help people maintain a behavior as part of a new habit, although more research is needed in this area (Miafodzyeva and Brandt, 2013; Samdal et al., 2017). A systematic review of behavioral change theories found that people need at least one sustained motivator to maintain a behavior change, and will often initiate a change when motivation is high and effort is low (Kwasnicka et al., 2016). This study also suggests that when motivation decreases and effort or costs increase, people will often need some way to self-monitor in order to sustain the change; this can be challenging when stress, fatigue, or financial pressures exert countervailing influences. Once a new behavior becomes a habit, external factors (e.g., changes in motivation or effort) are less likely to affect that behavior, and stable contexts can make behavior maintenance easier (Kwasnicka et al., 2016). These findings suggest the importance of

___________________

2 Habits are context–behavior associations in memory that develop as people repeatedly experience rewards for a given action in a given context. Habitual behavior is cued directly by context and does not require supporting goals and conscious intentions (Mazar and Wood, 2018).

carrying out further work to identify drivers related to the adoption and maintenance of new habits (Nisa et al., 2019) and of considering the role of habits in food waste behaviors and their interaction with the motivation, opportunity, and ability elements of the MOA framework.

UNDERSTANDING CONSUMERS’ FOOD WASTE BEHAVIOR

With the above findings from the six related domains in mind, the committee reviewed the literature specific to drivers of food waste, both in the household and away from home (see Appendix B for details on the search approach) to identify drivers and specific causal mechanisms that result in food waste and prioritize them by level of impact. The research focused on food waste is limited and emerging, and as discussed at the close of this chapter, the existing evidence did not support the development of so precise a list. However, the available literature does offer some important insights to guide further exploration of drivers of consumers’ food waste behavior from a systems perspective, as well as an approach to guide the design of interventions to reduce food waste at the consumer level and the additional research needed to build on these ideas.

How Consumers Come to Waste Food: Modifiable Drivers

The committee reviewed the literature on food waste at and away from home, including in K–12 school settings, colleges/universities, hospitals, hotels, and restaurants. Three systematic reviews of household food waste were particularly helpful (Roodhuyzen et al., 2017; Schanes et al., 2018; Stangherlin and de Barcellos, 2018). We used peer-reviewed studies with original data only to identify drivers of food waste outside the home because we could find no systematic review on that topic. These peer-reviewed studies focused largely on specific locations where food is discarded, such as schools and colleges, health care facilities, food service and restaurant venues, and cafeterias (e.g., Chen and Jai, 2018; Haas et al., 2014; Lorenz et al., 2017a,b). Through this review, we identified 160 drivers that research has suggested may be important contributors to consumer food waste.

To make their utility for the design of food waste reduction interventions more apparent, we clustered the individual drivers into categories, or summative drivers. Our focus was on identifying clusters of drivers that (1) reflect the importance of motivation, ability, and opportunity; (2) play an important role in determining consumer food waste behavior; and (3) might translate to interventions—that is, would potentially be modifiable. This process resulted in the identification of 11 summative drivers that evidence indicates are promising targets for reducing food waste, listed in Box 3-1.

Each of these 11 summative drivers represents a cluster of drivers synthesized from evidence across multiple studies covered in our search. Examples of individual drivers identified within each summative driver can be found in Tables 3-1 through 3-11, which are organized using the MOA framework described in Chapter 1. These examples are meant to depict the primary element (i.e., motivation, opportunity, or ability) by which the specific driver works. These examples also show how the drivers relate to the key ways consumers interact with food: acquiring, consuming and storing, and disposing of it. Because the studies we examined relied on a variety of methods it was not possible to estimate effect sizes for each or to prioritize them, a point discussed at the close of the chapter.

The drivers of food waste behavior interact with each other, and it is these more complex interrelationships that will result in an increase or decrease in food waste. For example, while meal planning may reduce food waste for some households, for others it might have the opposite effect, depending on resource availability, such as access to shopping opportunities created by the built environment (summative driver J) or food preferences (summative driver F). Thus, for example, people who can only make one large shopping trip in a distant location may, in planning, err on the side of buying too much, leading to later food waste. On the other hand, for a

consumer whose preferences simply include a large amount of perishable food, making a firm shopping plan may have little effect on that individual’s level of food waste. Because the interactions among the drivers are important, the distinctions among them can sometimes blur; nonetheless, identifying the categories of drivers is important for understanding the full range of drivers (and their mechanisms) influencing food waste behavior.

As in the research from related fields, the food waste literature suggests that it is important to consider underlying contextual factors to gain an understanding of the influence of various drivers on consumers’ food waste behavior. Some evidence suggests that drivers influence the generation of wasted food differently, and to varying degrees, depending on whether consumers are at or away from home. The material qualities of the food itself also mediate how multiple drivers influence the generation of wasted food. For example, whether a food item is fresh or frozen can influence relationships with—and thus the drivers of behaviors with—that food because fresh and frozen foods require different skills for storage and preparation and have different shelf lives.

A. Consumers’ Knowledge, Skills, and Tools

If they are to reduce waste, consumers need knowledge of what to do; the requisite skills to do it; and tools that do not unintentionally prompt waste (e.g., ability and opportunity), such as trays in a buffet setting or a large casserole dish used in food preparation (Hebrok and Boks, 2017; Roodhuyzen et al., 2017; Schanes et al., 2018) (see examples for specific drivers in Table 3-1). Important knowledge and skills are commonly related to provisioning and preparing the appropriate amount of food (e.g., Secondi et al., 2015); gauging quality; maximizing shelf life (e.g., Farr-Wharton et al., 2014); cooking, including repurposing of leftovers (e.g., Graham-Rowe et al., 2014); and awareness of which parts of food are edible.3 Consumer tools can be physical objects, informational tools (e.g., recipes), or technological tools (e.g., smartphone apps) that support planning, acquisition, storage, and preparation. Such tools may be transportable and expendable (e.g., storage containers, planning and monitoring tools, appropriately sized cookware or plates [Hebrok and Boks, 2017]). Note that because they may have strong effects on other aspects of the food supply, more durable tools are considered part of the built environment (e.g., refrigerator, cupboard storage) (see summative driver J below), and that tools that facilitate food waste monitoring are included in summative driver D.

___________________

3 Perceptions of which foods are edible are also relevant to food preferences, discussed together with knowledge and cultural norms below.

TABLE 3-1 Examples of Drivers Related to Knowledge, Skills, and Tools

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Recipes or other tools/information that encourage the purchase and full use of food items to acquire or prepare | Size of plate, cookware, or other item, prompting acquisition or preparation | Knowledge about quantities or food types needed for preparation, including the amount of previously acquired food that is usable |

| Consumption/Storage | Recipes, cooking shows, and other information sources that encourage limited consumption of foods |

Access to waste-reducing consumption modes (e.g., food sharing)

Access to storage tools and methods to maximize shelf life |

Knowledge about using “scraps,” aging food, leftovers, or edible components of food instead of disposing of them, and ways to maximize shelf life |

| Disposal | Access to trash cans and other bins for other means of waste management (e.g., composting) |

B. Consumers’ Capacity to Assess Risks Associated with Food Waste

People’s perceptions of food safety and quality, their sensitivity to guidance about food safety (e.g., Milne, 2012; Soma, 2017), and their knowledge about foodborne illnesses all influence food waste. In a national survey conducted in 2015, food safety and food quality were cited as the top two reasons for discarding food (Neff et al., 2015), although there is often a perceived tension between concerns related to reducing risk and those related to minimizing waste (Watson and Meah, 2013). People use knowledge, tools (e.g., date labels), and their senses to assess whether it is too risky to eat food (Hebrok and Boks, 2017). Assessment of risk affects both disposal and acquisition, and is influenced by such factors as recall of past experiences, norms, prior beliefs, date labels, and the smell and appearance of the food (Hebrok and Boks, 2017).

The process of judging whether food is safe to eat also relates to dietary restrictions (summative driver F), as some people are more risk averse or sensitive with respect to food relative to others. Perception of the risk or desirability of food is also related to psychosocial norms (summative driver I), as decisions related to risk management are also determined by emotions

and norms, such as the good provider identity4 (Brook Lyndhurst, 2011). Examples of specific drivers are in Table 3-2.

C. Consumers’ Goals with Respect to Food and Nutrition

Consumers must reckon with multiple motivations related to food consumption and waste, including eating more healthfully, reducing environmental impacts, and saving money. Some motivations reinforce each other, while others conflict. For example, the goals of saving money and reducing food waste would appear to be well aligned. However, getting the best value from food purchases through bulk purchasing or taking advantage of reduced prices may at times conflict with suggested food waste prevention techniques that encourage customers to buy only the perishable items they need. Other consumers might be motivated to lose weight, and therefore be more likely to leave edible food on the plate. Examples of specific drivers related to conflicting goals are in Table 3-3).

Consumers resolve such conflicts in a variety of ways. For example, psychological licensing allows individuals to feel justified or even good about discarding food if they engage in such desirable behaviors as composting

TABLE 3-2 Examples of Drivers Related to Capacity to Assess Risks

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Perceptions about which foods/food formats (frozen, canned, fresh) will be safest for the longest time | Knowledge of foods/formats that will be safest for the longest time | |

| Consumption/Storage |

Sensory cue interpretation and sensitivity

Interpretation of date labels Previous negative experiences and concerns about food safety |

Understanding of sensory cues

Understanding of the meaning of date labels |

|

| Disposal |

___________________

4 Good provider identity refers to the need to feel like a “good” provider and minimize any feelings of guilt experienced if individuals fail to meet personal or cultural expectations (e.g., Graham-Rowe et al., 2014).

(e.g., Qi and Roe, 2017), although this licensing is not inevitable. For example, if an action to reduce food waste activates a positive identity (e.g., makes one see oneself as a “smart consumer” or “food steward”), that self-consistency may be more powerful than the licensing effect, making behavior to reduce food waste more likely (Oyserman, 2015). At the same time, negative emotions about wasting food (e.g., guilt) may paradoxically have a licensing effect, allowing consumers to feel they have compensated for the waste with negative emotions (see, e.g., Russell et al., 2017).

Consumers’ motivations can also change through the consumption process. For instance, the motivation to eat healthfully can drive consumers to overpurchase produce that is later wasted when it begins to spoil or ends up not being a preferred item (e.g., Evans, 2011; Watson and Meah, 2013) perhaps because the desire for convenience or comfort comes to the fore after the food has been purchased. However, evidence suggests that health goals may align with waste prevention goals, and could be used to reinforce each other (Quested and Luzecka, 2014; von Massow et al., 2019).

Out-of-home environments trigger different goals relative to in-home environments (e.g., hedonic eating,5 maximizing the matching of food to the consumers’ preference, impression management goals that lean toward “leaving some food on the plate” in public). As a result, consumers’ waste reduction goals are often undermined in such contexts.

This cluster of drivers is closely linked to psychosocial and identity factors (summative driver I), which include the good provider identity and the perception that “fresh,” or more perishable, food is healthier than other forms of food (Schanes et al., 2018) (e.g., see Chapter 2).

D. Consumers’ Recognition and Monitoring of Their Food Waste

People may be unaware of the amount of food they discard and the impact of that waste because they lack the capacity to track what is wasted, and many believe they waste less than other people do (Neff et al., 2015). Consumers who do not perceive their food waste as a problem are unlikely to practice specific behaviors to reduce it (Brook Lyndhurst, 2007; Hebrok and Boks, 2017; Roodhuyzen et al., 2017; Schanes et al., 2018). In addition, although food suppliers may have tools for monitoring or reporting waste amounts, they have little incentive to remind consumers that overacquisition may lead to waste. For example, immediate removal of unconsumed food from the dining area of an out-of-home venue may be a norm that encourages further waste. Moreover, waste estimation is not generally considered part of a positive, hedonic social experience, making

___________________

5 Hedonic eating is the act of eating for pleasure, rather than simply for nourishment, and may cause and perpetuate overconsumption.

TABLE 3-3 Examples of Drivers Related to Consumers’ Food and Nutrition Goals

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition |

Desire to seek variety/explore new options

Beliefs about the relative effects of differently preserved foods on the ability to reach health goals (e.g., perishable fruits and vegetables “healthier” than other preparations) |

||

| Consumption/Storage |

(Mis)match between goals at acquisition (e.g., eating healthier) and goals at consumption (e.g., self-gifting or maximizing individual enjoyment from food)

“Healthy” choices in acquisition may license underconsumption of perishable foods Desire to lose weight, which leads to leaving food on one’s plate |

||

| Disposal |

Composting satisfies environmental and waste-reduction goals, licensing food waste

“Virtue” goals are satisfied by guilt about not eating, licensing disposal Discarding or “cleaning out” seen as a healthy, clean, or efficient action |

it unlikely that the data on waste collected in such venues will be shared with consumers.

The invisibility of food waste may be compounded when other waste is made more visible. For example, consumers who are trying to gauge their food waste may be distracted by the waste generated by bulky packaging, which appears to be of greater magnitude than their wasted food. In this case, consumers may overlook the important role packaging can play in reducing food waste (see also Chapter 2 on myths). Although it is generally agreed that people are unaware of their waste generation, it remains unclear whether this is purely a result of the invisibility of waste generation or is also a result of willful ignorance stemming from a desire to alleviate guilt or other negative emotions associated with wasting food. Examples of specific drivers are in Table 3-4.

TABLE 3-4 Examples of Drivers Related to Individuals’ Recognition and Monitoring of Their Food Waste

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Lack of acquisition-proximal, salient reminders of the economic and opportunity costs of personal past food waste Belief that one’s own food waste is less than that of others | ||

| Consumption/Storage | Immediate removal of wasted food from the consumption area, which results in lack of feedback | ||

| Disposal |

Removal/processing of food by a third party, which results in lack of feedback

Belief that another type of waste (e.g., packaging) is more important than food waste |

Use of waste monitoring tools |

E. Consumers’ Psychological Distance from Food Production and Disposal

A lack of intellectual, social, and emotional linkage with food—a lack of appreciation of the connections among its production, consumption, and disposal—can result in a lack of awareness of or concern about the consequences of discarding food (e.g., Clapp, 2002; Soma, 2017) (see specific examples in Table 3-5). Moreover, urbanization and the changing structure of the food supply chain have generally resulted in physical distance between where people live and sites of food production (e.g., farms) and disposal (e.g., landfills), further reinforcing this psychological disconnect (see Box 3-2). Consuming food away from home or shopping online, with no personal connection with those who prepared the food, also serves to distance consumers psychologically.

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | “Inexpensive food” is overacquired because of devaluation of labor and resources involved in the product life cycle | ||

| Consumption/Storage |

Disconnect from the preparer leads to devaluation of food and lower consumption

Consequences of food waste do not affect many personally |

||

| Disposal | Poor awareness of the impacts of disposal |

F. Heterogeneity of Consumers’ Food Preferences and Diets

Food preferences are driven by expectations and norms and by the desire for tasty or satisfying food. Preferences can lead to wasted food—for example, the discarding of portions of food, such as broccoli stalks or apple cores, that could be eaten (knowledge of what is edible is also closely linked to consumers’ knowledge and skills, discussed above). As noted previously, the classification of food as edible or inedible is shaped by both material and sociocultural factors that vary significantly among and within cultures (Gillick and Quested, 2018; Moreno et al., 2020; Papargyropoulou et al., 2014). Therefore, these attitudes offer a leverage point for interventions to motivate consumers to reduce food waste.

Children’s limited palates and their often picky and unpredictable eating habits are commonly cited as a reason for wasting food (Hebrok and Boks, 2017; Roodhuyzen et al., 2017; Schanes et al., 2018). As children develop their eating habits, they often need to try foods—especially vegetables and other foods considered to be healthy—several times before liking them (Wardle et al., 2003). As a result, it may be socially optimal to allow some level of food waste as children develop their palates, especially if it results in healthier overall eating habits. Specific examples of drivers are listed in Table 3-6.

TABLE 3-6 Examples of Drivers Related to Heterogeneity of Consumers’ Food Preferences and Diets

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Desire to match heterogeneous preferences and diets | ||

| Consumption/Storage |

Rejection of previously purchased food in light of changes in diet or preference

Dislike of consuming leftovers or certain food parts Desire to alter one’s diet |

Specific foods needed to account for dietary restrictions

Limited palates of children |

Adoption of unfamiliar foods or diets |

| Disposal |

G. The Convenience or Inconvenience of Reducing Food Waste as Part of Daily Activities

Contexts, priorities, and other characteristics of households and individuals—including the many demands associated with working and maintaining a household—influence consumer choices with respect to food waste (see some examples of drivers in Table 3-7). These factors are affected in turn by dynamics within a household and communication among household members (e.g., Evans, 2011; Ganglbauer et al., 2013; Hebrok and Heidenstrøm, 2019). See Box 3-3 for more on how consumers make decisions and establish priorities.

Several behavior-related theories and mechanisms have been proposed to explain these influences (Becker, 1965; Reid, 1934). A key insight of this work is that transforming market goods (e.g., packages of food) into home-produced goods (e.g., a meal) requires household members’ time, which could otherwise be used to generate income through paid work, engage in other aspects of home production, or enjoy leisure activities. Further, household members’ skill in household production can alter the trade-off and eventual decisions made with respect to allocating scarce time across market and home activities. The time available for food acquisition and preparation and the skills of household members therefore determines the motivation, opportunity, and ability to decrease food waste.

The household production theory (Becker, 1965) has been used to model households’ food waste (Lusk and Ellison, 2017), guide systems-based

assessments of the economic impacts of wasted food (Muth et al., 2019), develop hypotheses about household changes in the amount of food wasted in response to changes in food prices and policies (Hamilton and Richards, 2019), and devise tax schemes to reduce food waste (Katare et al., 2017). This framework has also supported efforts to estimate the amount of wasted food generated by a household based on detailed information about food purchases and demographic profiles (Landry and Smith, 2018; Yu and Jaenicke, 2018).

H. Marketing Practices and Tactics that Shape Consumers’ Food Behaviors

Consumer choice is significantly influenced by product branding, pricing, promotions, and other actions of retailers, restaurant operators, and other away-from-home food providers (examples of specific drivers are in Table 3-8). Marketing research has identified both online and in-store tactics that encourage overacquisition or suboptimal acquisition that may shape both at- and away-from-home behaviors. Marketing strategies that relate to food waste in particular include special offers, multiple-unit pricing, packaging, signage and displays, large portion sizes, bundled deals, and

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | Intermittent scarcity of resources (e.g., money) and time leads to stockpiling |

In-store/restaurant overload prompts satisficinga/use of heuristics

Cognitive availability biases estimation of desire/need |

|

| Consumption/Storage | Substitution of food delivery for food preparation because of preference | Meal plan abandonment due to variation in needs and circumstances | Cognitive load or stress leads to reliance on memory, and food is not consumed if it is not visible |

| Disposal | Reliance on affect heuristics to determine freshness or usability | Cost and ease of use of disposal and discard options | Time pressure leads to disposal before consumption is complete |

a Satisficing is a decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory or adequate result, rather than an optimal solution.

cues to seek variety or shop in an exploratory manner. For example, low prices and deep discounts, while increasing consumers’ spending power, also can lead to stockpiling. Past research has shown that promotions with high quantity anchors (e.g., limit of 10 mangoes) cue consumers to purchase more of the promoted product than they otherwise might (Wansink et al., 1998). Retailers also often encourage consumers to seek variety, which can increase the likelihood that they will purchase nonpreferred foods that are more likely to go to waste (Ratner et al., 1999).

Marketing tactics operate at both conscious and nonconscious levels (e.g., Kahneman, 2011). For example, buy one, get one free deals can lead consumers to purchase—and waste—more, through a decision of which they are conscious. Other tactics, however, such as those that rely on high purchase anchors, may nudge consumers to buy more without their being aware of the influence on their decision. Likewise, larger carts and larger servings may lead to waste in both conscious and unconscious ways, as consumers may recognize the effects of such tactics on their propensity to buy food that will go uneaten but still be influenced.

Similar tactics can be used to reduce waste if developed wisely. For example, marketing researchers have shown that granular, modular packaging, which allows consumers to eat smaller portions of a food without

leaving the entire quantity open to decay, will reduce the likelihood of waste. Because this tactic will also increase packaging and thus nonfood waste, however, this potential trade-off should be accounted for in evaluation of the intervention’s efficacy. Innovative processing technologies are continually being developed to meet various objectives (e.g., food safety), and they directly influence how consumers buy, prepare, and store their food. Many of these technologies have made an impact in increasing shelf life and thereby decreasing food waste (see Chapter 2). Other marketing factors, however, have not been widely used to shape waste during the consumption or disposal stage, so there is an opportunity to use marketing tactics that have both a conscious and unconscious influence on food waste.

I. Psychosocial and Identity-Related Norms Relevant to Food Consumption and Waste

Consumers’ motivation to reduce food waste is shaped by social norms, identity, and habit (examples of drivers related to norms are in Table 3-9). Factors that create identity and habit play an important role (e.g., Russell et al., 2017). These include formative life experiences, such as food scarcity, exposure to food production (e.g., through gardening or hunting), and local culture. Habits (actions performed automatically) also play a key role in many of the psychosocial and identity-related behaviors related to wasting food (Quested et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2017).

Norms6—social expectations that define the appropriate behavior in a given situation (Schwartz, 1977)—appear to be particularly influential and have been the most extensively studied among this cluster of factors. When norms are activated, often outside of conscious awareness, they influence information processing and decision making. Norm activation theory would suggest, for example, that a food acquisition situation may activate expectations about the desirability of larger shopping baskets, the benefits of bulk buying or abundance, or the acceptability of excess that influence the likelihood that individuals will acquire more than they need. Norms that can lead to waste include the good provider identity discussed earlier (e.g., Graham-Rowe et al., 2014), gender roles, consumerism (the idea that consumption of goods is positive), acceptance of wasting food as “normal,” lack of acceptance of imperfect foods (e.g., Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2018), and preferences for fresh food. Stern (2000) argues that because the role of norms in food-related behavior is so substantial, it is critical not only to

___________________

6 “Norms” in this context refers to moral norms (i.e., when people feel that doing something aligns with an abstract right or wrong), injunctive social norms (i.e., feelings about what one ought to do), and descriptive social norms (i.e., perceptions of what most people are doing) that are strongly correlated with behavior.

TABLE 3-8 Examples of Drivers Related to Marketing Practices and Tactics

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition |

High promotional anchors (e.g., purchase limit 10, 10 for $10) and price promotions

Novelty promotions promoting purchase of atypical/unfamiliar foods Messaging that emphasizes freshness, abundance, attractive presentation, minimal packaging, or organic products without regard to effects on waste Packaging and product offerings that result in acquiring more than desired Retail standards that promote only aesthetically appealing food |

||

| Consumption/Storage |

No packaging information provided related to preparation, storage, or usage

Packaging not optimized for storage |

||

| Disposal |

discuss explicit attitudes and knowledge but also to address more implicit religious and moral norms.

Some research indicates that individuals may face conflicting norms in the domain of food waste. For example, consumers may regard accumulation of goods as important to personal happiness and social status but also hold religious norms about the value of temperance (Petrescu-Mag et al., 2019) or find waste generally aversive (Arkes, 1996). Thus, norm activation theory suggest that waste may be reduced if planful shopping (Stefan et al., 2013) or an “ethic of thrift” (Waston and Meah, 2013) is made normative. Other research, however, suggests that norms may play a less important a role in food waste relative to such factors as price and convenience (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2018).

Although survey and experimental data are often focused on the decisions individuals make on their own, food acquisition and consumption decisions are often made in dyadic or group contexts, in which acquisition and consumption decisions are likely to be radically different from those made individually. For example, it has been suggested that individuals making decisions in groups or when others can observe are likely to differentiate themselves from others (e.g., not order an item another individual in the group has ordered) and to signal their own personality by seeking variety across food choices (Ariely and Levav, 2000; Ratner et al., 1999). Choosing items for reasons other than preference increases the likelihood of waste, although acquisition and consumption in groups may also serve to reduce waste in that when acquisition choices are observed by others, more communal consumers may be prompted to exert self-control, thus tempering their acquisition tendencies (Kurt et al., 2011).

J. Factors in the Built Environment and the Food Supply Chain

The built environment7 and the food supply chain play a key role in food waste through factors ranging from the household or community level (e.g., layout of home kitchen, refrigerator capacity, access to retail food sources) to the societal level (e.g., urbanization, characteristics of the food supply chain). For example, space constraints in the refrigerator or cupboards can make it difficult to organize items, thus making them more difficult to find and therefore less likely to be eaten (e.g., Schanes et al., 2018) (see additional examples in Table 3-10). Individuals often have

___________________

7 “Built environment” refers to the human-made environment that provides the setting for human activity, ranging in scale from buildings to cities and beyond. It has been defined as “the human-made space in which people live, work and recreate on a day-to-day basis (Roof and Oleru, 2008).

TABLE 3-9 Examples of Drivers Related to Psychosocial and Identity-Related Norms

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition |

Social and gender norms related to abundance, special occasions, and the good provider identity

Individual aversion to scarcity (i.e., acquiring too much as “insurance”) Acquisition as a marker of status/consumerism Lack of acceptance of imperfect or suboptimal foods |

||

| Consumption/Storage |

Norms related to the good provider identity, abundance, and “good” food

Acceptance of imperfect or suboptimal foods Acceptance of food sharing Eating leftovers perceived by some as sacrifice or thrift Desire to impress eating companions (e.g., taking leftovers instead of leaving them) Prior experiences and local food cultures that influence habit creation |

||

| Disposal |

Waste acceptance norms

Guilt associated with waste |

limited control over these factors, which shape the context for many kinds of food choices.

Aspects of the built environment and the food supply chain can be addressed through policies or technological improvements, but intervening in a complex system brings a risk of unintended consequences. System-wide responses may offset a positive original intent or expected impact, through rebound effects, for example. This point is illustrated in the context of energy conservation by the introduction of technology that enables people to afford to drive more by using less fuel for each trip. Furthermore, if enough drivers experience this improved efficiency, the market price of fuel will likely decline, making additional trips even less expensive.8

In the context of food waste, interventions that successfully reduce the amount of wasted food could result in a smaller reduction in greenhouse gas emissions than expected (unintended consequence) because consumers who spend less on food may redirect their spending to other consumer goods that generate greenhouse gases (Druckman et al., 2011). Other unintended consequences might include a rise in demand for electricity and an increase in greenhouse gas emissions if standard refrigerator temperatures are lowered. Thus, it is important that the entire food system be considered when factors in the built environment and the food supply chain are used to address food waste.

K. Policies and Regulations at All Levels of Government

Policies and goals related to food and waste, including date labeling, waste management systems and regulations, urban planning choices, agricultural subsidies, and other market-based instruments, have a key role to play in reducing food waste (some examples related to policy and regulations are listed in Table 3-11). Such elements of the food supply system as the cost of food and access to waste management services provide the context within which consumers and industry make choices. Some policies may directly target waste, while others are related to food quality, prices, or other factors and may indirectly influence the generation of wasted food. Broadly, policies have the potential to both drive and prevent the generation of wasted food, as well as to address equity issues, or the possibility that groups of people may be disproportionately affected by changes (e.g., through regressive taxes). One policy recently recognized as important is date labeling on packages (e.g., Milne, 2012; Neff et al., 2019; Thompson

___________________

8 Since Jevons hypothesized that improved efficiency of coal engines might actually lead to an increase in coal use (Jevons, 1866), economists and engineers have hypothesized about and documented such offsetting responses, largely in the context of energy conservation initiatives (Binswanger, 2001; Chan and Gillingham, 2015; Greening et al., 2000; Khazzoom, 1980).

TABLE 3-10 Examples of Drivers Related to the Built Environment and the Food Supply Chain

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition |

Urban planning factors, including access to transportation

Access to, types of, and distance from retail outlets Available food supply, including access to garden or other food production |

||

| Consumption/Storage | Access to and layout of home refrigerator and refrigerator or freezer design, including capacity | ||

| Disposal | Access to waste management products and services |

et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017). Another is waste management. These policies focus on what happens to food once it has been wasted by the consumer, but they can influence choices made along the entire supply chain. Commonly suggested waste management policies include imposing higher costs for landfill disposal (e.g., through a tipping fee), banning organic materials (including food waste) from landfills (e.g., Sandson and Broad Leib, 2019), requiring mandatory collection of compostable materials, and using pricing schemes that charge customers by the amount of waste generated. Relatively little is known, however, about the direct impact of specific policies and regulations on the generation of wasted food (Schanes et al., 2018; Spang et al., 2019).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The committee examined a wide range of research on factors that influence consumer behavior to identify those that may promote behaviors that limit food waste. These factors operate both at the individual, intrapersonal, and interpersonal levels and at the broad community, state, and federal levels, and they interact with one another.

TABLE 3-11 Examples of Drivers Related to Policies and Regulations

| Stage | Motivation | Opportunity | Ability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition |

Agricultural subsidies, tariffs, and import restrictions that influence price and availability

Economic trends that influence purchasing and consumption patterns Requirements of retailers and food sellers to disclose information about food (e.g., calorie count) or provide food in a certain way |

Unregulated or inconsistent date labeling | |

| Consumption/Storage | |||

| Disposal | Economic trends that influence waste production | Access to waste management services and restrictions on (e.g., organic bans) or requirements for (e.g., pay-as-you-throw) discard |

The MOA framework offers possibilities for analyzing this complex array of drivers of food waste behavior. As discussed in Chapter 1, this framework posits that behavioral changes occur as a result of the interplay of these three influences. In the context of consumer behavior related to wasting food, the MOA framework suggests that if consumers are to reduce food waste, they need to have the opportunity and ability to do so, and also be motivated to do so. At the same time, the framework highlights that many other factors that increase or decrease food waste—particularly nonconscious influences, habits, and contextual and psychosocial factors—may be at play when motivation, opportunity, or ability is low. The MOA framework is flexible enough to support comparison of findings across diverse literatures and thereby allow for consideration of these additional mediating factors.

Analysis of findings from the literature on drivers of consumer behavior with the MOA framework in mind yielded the following overall observations.

Drivers of food waste collectively influence consumer behavior regarding food acquisition, consumption and storage, and disposal. Although some drivers, such as marketing factors, shape primarily acquisition tendencies, others, such as the built environment, play strong roles in shaping acquisition, consumption, and disposal. Thus, drivers can emerge at different stages of a consumer’s experience with food, and can play different roles depending on the stage in which they appear. The fact that drivers operate differently at different points in a process can make it difficult to make clear prescriptions about the likely effects of any single intervention strategy. However, it also highlights the potential benefits of addressing multiple points through a single driver or small number of drivers—for example, promoting efficient acquisition and maximizing of consumption while working to prevent the discarding of food in particular situations. As a systems analysis would suggest, all influences on the consumer’s experience, including those that operate long before the actual decision to discard occurs, should be taken into account so that addressing a driver in one stage of the consumer’s experience with food will not create problems in another (e.g., altering acquisition in ways that promote more disposal).

The largest proportion of drivers addressed by research relate to motivation, but it is clear that drivers may also affect opportunity and ability. While the importance of motivation is clear, behavior cannot be disconnected from opportunity and ability. Findings from the six related domains explored by the committee show that motivations are crucial drivers of behavior, but that they work in concert with opportunity and ability. The focus on opportunity and ability is particularly important in the context of automatic behaviors or habits, and the need to sustain—not just initiate—desired behaviors. However, research in the food waste domain has not systematically compared drivers of automatic versus reflective behavior, or distinguished between drivers that support initiation as opposed to maintenance of behavior.

The existing research does not cover all potential drivers of consumer behavior across settings. While this chapter has attempted to suggest possible drivers of food waste behavior that may operate in away-from-home consumption, little empirical research has focused on these drivers explicitly or systematically. Similarly, research in the six related domains has

not adequately explored how drivers differ over time and across settings. Research in the other domains also indicates the importance of understanding contextual factors, which may reveal a given driver’s operation or change the way any given driver works. Further, examining drivers in only one setting makes it more difficult to understand how a single driver may operate in others. For example, if it is possible to address drivers that prompt away-from-home food waste, consumers may internalize changes in practices and mindsets that affect the drivers existing at home. Additional research may broaden investigation into how drivers identified in this report—and others yet to be identified—operate within different contexts, as well as across settings.

Examination of underlying psychological and contextual drivers may provide deeper understanding than can sociodemographic factors. Researchers in the six related domains have found that sociodemographic variables by themselves are often inadequate or poor predictors of environment-related behaviors, and the same appears to be true for food waste behaviors (see Chapter 2). Many drivers of food waste behavior, such as social norms, tool availability, and the built environment, may be correlated with sociodemographic factors, but the former are most likely to explain the behavior.

The research reviewed does not support prioritizing some drivers above others, but it does provide clues for identifying and using drivers that might be operating in a given situation. Because methods and measures used in this research vary so widely, it is difficult to compare effect sizes across studies. Further, as few studies consider more than one driver simultaneously, the committee was unable to conduct a systems analysis that would account for dynamics and relationships. The 11 summative drivers identified in this chapter each affect at least one of the three elements of the MOA framework—motivation, opportunity, and ability, as illustrated in Figure 3-1.

With this in mind, the committee proposes that findings in this chapter can be used to identify and target drivers on which to focus interventions for reducing consumer-level food waste. To identify the relevant drivers, designers of interventions for a specific setting or community could conduct formative research in that community to identify the cognitive process driving a food waste behavior (e.g., reflective or automatic) and which element(s) of the MOA framework are predominant.

In a hypothetical case, individuals in a community may report both a high sense of psychological distance from a food source and a conscious willingness to discard food once it has become aesthetically imperfect. In this case, researchers may find that, for these individuals, psychological distance results in the lack of motivation to use the food and thus food waste. This behavior appears to be more reflective than automatic, and

other drivers are therefore likely at play because reflective behaviors require activation of all three elements of the MOA framework. Thus, although it may be tempting to launch a messaging campaign focused solely on enhancing motivation to reduce the discarding of food, the intervention designer should also search for drivers in the community that may be resulting in the high ability (e.g., low food literacy) and easy opportunity (e.g., lack of incentives to save food) to discard food. In this way, the most promising intervention for this context would not only change the psychological distance from food through motivational cues, but also address drivers related to opportunity and ability that might be promoting food waste.

On the other hand, consider a hypothetical case in which food waste is likely to be driven predominantly by automatic processes. In contrast with the above case, food waste here is occurring without the consumer’s awareness (so that researchers might find, for example, a large gap between self-reported and objective measures of food waste); opportunity and ability, rather than motivation, are likely to be at play. For example, researchers might find large, convenient trash bins placed near refrigerators, indicating that individuals have high opportunity to discard the food; removing such sources of easy opportunity might prompt consumers to process their options more reflectively. Intervention designers might also look for evidence of a link between habits and a given event or cue. If that link could be disrupted, the interventionist might then engage consumers in more active behavioral change. As an example, researchers might find that some individuals dispose of food too soon because of a calendar cue to clean the refrigerator on the first of the month, the calendar itself triggering the habit and the reward of a clean, spacious refrigerator. In this case, this old habit could be replaced with a new one. An intervention could be designed to interrupt the connection between the cue (the calendar) and the behavior (cleaning out the refrigerator)—for example, by renaming the first of the month “Leftover Day” and providing rewards for using rather than discarding leftovers and creative recipes for using the food.

In both of these examples, successful interventions are likely to result from a systematic approach to addressing multiple drivers of consumers’ food waste behavior. Further, it may not always be simple to determine whether waste is occurring only automatically or reflectively, and in any given community, both are likely to occur. Research that captures the drivers and the relative prevalence of such processes is critical to understanding how interventions should be bundled.

CONCLUSION 3-1: Consumer behaviors regarding food acquisition, consumption, storage, and disposal are complex; depend on context; and are driven by multiple, interacting individual, sociocultural, and material factors within and outside the food system. These drivers of

behavior can best be understood as affecting consumers’ motivation, ability, and opportunity to reduce food waste, through both reflective and automatic processes.

CONCLUSION 3-2: The incomplete and limited research on drivers of food waste at the consumer level does not support prioritization of particular drivers of consumers’ food waste behaviors over others, but understanding of how the 11 summative drivers identified in Box 3-1 combine to influence those behaviors can reveal promising targets for interventions to reduce food waste at the consumer level.

REFERENCES

Abrahamse, W., and L. Steg. 2013. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Global Environmental Change 23(6):1773-1785.

Addo, I.B., M.C. Thoms, and M. Parsons. 2018. Household water use and conservation behavior: A meta-analysis. Water Resources Research 54(10):8381-8400.

Amato, M., R. Fasanelli, and R. Riverso. 2019. Emotional profiling for segmenting consumers: The case of household food waste. Calitatea 20(S2):27-32.

Ariely, D., and J. Levav. 2000. Sequential choice in group settings: Taking the road less traveled and less enjoyed. Journal of Consumer Research 27(3):279-290.

Arkes, H.R. 1996. The psychology of waste. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 9(3):213-224.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., A. Giménez, and G. Ares. 2018. Convenience or price orientation? Consumer characteristics influencing food waste behaviour in the context of an emerging country and the impact on future sustainability of the global food sector. Global Environmental Change 49:85-94.

Becker, G.S. 1965. A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal 75(299):493-517.

Binswanger, M. 2001. Technological progress and sustainable development: What about the rebound effect? Ecological Economics 36(1):119-132.

Brook Lyndhurst. 2007. Food Behaviour Consumer Research: Quantitative Phase. Available: https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Food%20behaviour%20consumer%20research%20quantitative%20jun%202007.pdf.

Brook Lyndhurst. 2011. Consumer Insight: Date Labels and Storage Guidance. Available: https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Technical%20report%20dates.pdf.

Chan, N., and K. Gillingham. 2015. The microeconomic theory of the rebound effect and its welfare implications. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2:133-159.

Chen, H.S., and T.M.C. Jai. 2018. Waste less, enjoy more: Forming a messaging campaign and reducing food waste in restaurants. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism 19(4):495-520.

Clapp, J. 2002. The distancing of waste: Overconsumption in a global economy. In Confronting Consumption, edited by T. Princen, M. Maniates and K. Conca. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Pp. 155-176.

Cox, J., S. Giorgi, V. Sharp, K. Strange, D.C. Wilson, and N. Blakey. 2010. Household waste prevention: A review of evidence. Waste Management and Research 28(3):193-219.

Druckman, A., M. Chitnis, S. Sorrell, and T. Jackson. 2011. Missing carbon reductions? Exploring rebound and backfire effects in UK households. Energy Policy 39(6):3572-3581.

Evans, D. 2011. Beyond the throwaway society: Ordinary domestic practice and a sociological approach to household food waste. Sociology 46(1):41-56.

Farr-Wharton, G., M. Foth, and J.H.-J. Choi. 2014. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 13(6):393-402.

Ganglbauer, E., G. Fitzpatrick, and R. Comber. 2013. Negotiating food waste: Using a practice lens to inform design. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 20(2):Article 11.

Geiger, J.L., L. Steg, E. van der Werff, and A.B. Ünal. 2019. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. Journal of Environmental Psychology 64:78-97.

Gillick, S., and T.E. Quested. 2018. Household Food Waste: Restated Data for 2007-2015. WRAP. Available: https://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/Household%20food%20waste%20restated%20data%202007-2015%20FINAL.pdf.

Graham-Rowe, E., C.J. Donna, and S. Paul. 2014. Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 84(84):15-23.

Greening, L.A., D.L. Greene, and C. Difiglio. 2000. Energy efficiency and consumption: The rebound effect—A survey. Energy Policy 28(6):389-401.

Grewal, L., J. Hmurovic, C. Lamberton, and R.W. Reczek. 2019. The self-perception connection: Why consumers devalue unattractive produce. Journal of Marketing 83(1):89-107.

Haas, J., L. Cunningham-Sabo, and G. Auld. 2014. Plate waste and attitudes among high school lunch program participants. Journal of Child Nutrition and Management 38(1):n1.

Hamilton, S.F., and T.J. Richards. 2019. Food policy and household food waste. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 101(2):600-614.

Hebrok, M., and C. Boks. 2017. Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design: An extensive review. Journal of Cleaner Production 151:380-392.

Hebrok, M., and N. Heidenstrøm. 2019. Contextualising food waste prevention: Decisive moments within everyday practices. Journal of Cleaner Production 210:1435-1448.

Jevons, W.S. 1866. The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of our Coal-Mines. London: Macmillan.

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Macmillan.

Karlin, B., J.F. Zinger, and R. Ford. 2015. The effects of feedback on energy conservation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 141(6):1205-1227.

Katare, B., D. Serebrennikov, H. H. Wang, and M. Wetzstein. 2017. Social-optimal household food waste: Taxes and government incentives. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99(2):499-509.

Khazzoom, J.D. 1980. Economic implications of mandated efficiency in standards for household appliances. The Energy Journal 1(4):21-40.

Koop, S.H.A., A.J. Van Dorssen, and S. Brouwer. 2019. Enhancing domestic water conservation behaviour: A review of empirical studies on influencing tactics. Journal of Environmental Management 247:867-876.

Kurt, D., J.J. Inman, and J.J. Argo. 2011. The influence of friends on consumer spending: The role of agency–communion orientation and self-monitoring. Journal of Marketing Research 48(4):741-754.

Kwasnicka, D., S.U. Dombrowski, M. White, and F. Sniehotta. 2016. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review 10(3):277-296.

Landry, C., and T. Smith. 2018. Household Food Waste: Theory and Empirics. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3060838.

Li, D., L. Zhao, S. Ma, S. Shao, and L. Zhang. 2019. What influences an individual’s proenvironmental behavior? A literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 146:28-34.

Lorenz, B.A., M. Hartmann, S. Hirsch, O. Kanz, and N. Langen. 2017a. Determinants of plate leftovers in one German catering company. Sustainability (Switzerland) 9(5):807.

Lorenz, B.A.-S., M. Hartmann, and N. Langen. 2017b. What makes people leave their food? The interaction of personal and situational factors leading to plate leftovers in canteens. Appetite 116:45-56.

Lusk, J.L., and B. Ellison. 2017. A note on modelling household food waste behaviour. Applied Economics Letters 24(16):1199-1202.

Mazar, A., and W. Wood. 2018. Defining habit in psychology. In The Psychology of Habit: Theory, Mechanisms, Change, and Contexts, edited by B. Verplanken. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. Pp. 13-29.

Miafodzyeva, S., and N. Brandt. 2013. Recycling behaviour among householders: Synthesizing determinants via a meta-analysis. Waste and Biomass Valorization 4(2):221-235.

Milne, R. 2012. Arbiters of waste: Date labels, the consumer and knowing good, safe food. The Sociological Review 60(2 suppl):84-101.

Moreno, L.C., T. Tran, and M.D. Potts. 2020. Consider a broccoli stalk: How the concept of edibility influences quantification of household food waste. Journal of Environmental Management 256:109977.

Muth, M.K., C. Birney, A. Cuéllar, S.M. Finn, M. Freeman, J.N. Galloway, I. Gee, J. Gephart, K. Jones, L. Low, E. Meyer, Q. Read, T. Smith, K. Weitz, and S. Zoubek. 2019. A systems approach to assessing environmental and economic effects of food loss and waste interventions in the United States. Science of the Total Environment 685:1240-1254.

Nash, N., L. Whitmarsh, S. Capstick, T. Hargreaves, W. Poortinga, G. Thomas, E. Sautkina, and D. Xenias. 2017. Climate relevant behavioral spillover and the potential contribution of social practice theory. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 8(6):e481.

Neff, R.A., M.L. Spiker, and P.L. Truant. 2015. Wasted food: U.S. consumers’ reported awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. PLoS ONE 10(6).

Neff, R.A., M. Spiker, C. Rice, A. Schklair, S. Greenberg, and E. Broad Leib. 2019. Misunderstood food date labels and reported food discards: A survey of U.S. consumer attitudes and behaviors. Waste Management 86:123-132.

Nisa, C.F., J.J. Belanger, B.M. Schumpe, and D.G. Faller. 2019. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nature Communications 10(1):4545.

Oyserman, D. 2015. Identity-based motivation. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource, edited by R.A. Scott, S.M. Kosslyn, and M.C. Buchmann. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Papargyropoulou, E., R. Lozano, J.K. Steinberger, N. Wright, and Z. bin Ujang. 2014. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production 76:106-115.

Parfitt, J., M. Barthel, and S. Macnaughton. 2010. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365(1554):3065-3081.

Petrescu-Mag, R.M., D.C. Petrescu, and G.M. Robinson. 2019. Adopting temperance-oriented behavior? New possibilities for consumers and their food waste. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 32(1):5-26.

Princen, T. 2002. Distancing: Consumption and the severing of feedback. In Confronting Consumption, edited by T. Princen, M. Maniates, and K. Conca. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Pp. 103-131.

Qi, D., and B.E. Roe. 2017. Foodservice composting crowds out consumer food waste reduction behavior in a dining experiment. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99(5):1159-1171.

Quested, T.E., and P. Luzecka. 2014. Household Food and Drink Waste: A People Focus. WRAP. Available: https://www.wrap.org.uk/content/household-food-drink-waste-people-focus.

Quested, T.E., A. Parry, S. Easteal, and R. Swannell. 2011. Food and drink waste from households in the UK. Nutrition Bulletin 36(4):460-467.

Ratner, R.K., B.E. Kahn, and D. Kahneman. 1999. Choosing less-preferred experiences for the sake of variety. Journal of Consumer Research 26(1):1-15.

Reid, M.G. 1934. Economics of Household Production. Madison, WI: John Wiley & Sons.

Roodhuyzen, D.M.A., P.A. Luning, V. Fogliano, and L.P.A. Steenbekkers. 2017. Putting together the puzzle of consumer food waste: Towards an integral perspective. Trends in Food Science and Technology 68:37-50.

Roof, K., and N. Oleru. 2008. Public health: Seattle and King County’s push for the built environment. Journal of Environmental Health 71(1):24-27.

Russell, S.V., C.W. Young, K.L. Unsworth, and C. Robinson. 2017. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 125:107-114.

Samdal, G.B., G.E. Eide, T. Barth, G. Williams, and E. Meland. 2017. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults: Systematic review and meta-regression analyses. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14(1).

Sandson, K., and E. Broad Lieb. 2019. Bans and beyond: Designing and implementing organic waste bans and mandatory organics recycling laws. Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic, Center for EcoTechnology. Available: https://www.chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Organic-Waste-Bans_FINAL-compressed.pdf.

Schanes, K., K. Dobernig, and B. Gözet. 2018. Food waste matters: A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production 182:978-991.

Schwartz, S.H. 1977. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 10, edited by L. Berkowitz. Poole, UK: Academic Press. Pp. 221-279.

Secondi, L., L. Principato, and T. Laureti. 2015. Household food waste behaviour in EU-27 countries: A multilevel analysis. Food Policy 56:25-40.

Soderhorn, P. 2010. Environmental Policy and Household Behavior: Sustainability and Everyday Life. Abingdon, UK: Earthscan.

Soma, T. 2017. Gifting, ridding and the “everyday mundane”: The role of class and privilege in food waste generation in Indonesia. Local Environment 22(12):1444-1460.

Spang, E.S., L.C. Moreno, S.A. Pace, Y. Achmon, I. Donis-Gonzalez, W.A. Gosliner, M.P. Jablonski-Sheffield, M.A. Momin, T.E. Quested, K.S. Winans, and T.P. Tomich. 2019. Food loss and waste: Measurement, drivers, and solutions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 44(1):117-156.

Stangherlin, I.C., and M.D. de Barcellos. 2018. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. British Food Journal 120(10):2364-2387.

Stefan, V., E. van Herpen, A.A. Tudoran, and L. Läteenmäki. 2013. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Quality and Preference 28(1):375-381.

Stern, P. 2000. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. Journal of Social Issues 56(3):407-424.

Thompson, B., L. Toma, A.P. Barnes, and C. Revoredo-Giha. 2018. The effect of date labels on willingness to consume dairy products: Implications for food waste reduction. Waste Management 78:124-134.

Thyberg, K.L., and D.J. Tonjes. 2016. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 106:110-123.

Varotto, A., and A. Spagnolli. 2017. Psychological strategies to promote household recycling. A systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions. Journal of Environmental Psychology 51:168-188.

Verplanken, B. 2018. Psychology of Habit: Theory, Mechanisms, Change, and Contexts. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

von Massow, M., K. Parizeau, M. Gallant, M. Wickson, J. Haines, D. Ma, A. Wallace, N. Carroll, and A. Duncan. 2019. Valuing the multiple impacts of household food waste. Frontiers in Nutrition 6:143.

Wansink, B., R.J. Kent, and S.J. Hoch. 1998. An anchoring and adjustment model of purchase quantity decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 35(1):71-81.

Wardle, J., M.L. Herrera, L. Cooke, and E.L. Gibson. 2003. Modifying children’s food preferences: The effects of exposure and reward on acceptance of an unfamiliar vegetable. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57(2):341-348.

Watson, M., and A. Meah. 2013. Food, waste and safety: Negotiating conflicting social anxieties into the practices of domestic provisioning. The Sociological Review 61:102.

Whitmarsh, L.E., P. Haggar, and M. Thomas. 2018. Waste reduction behaviors at home, at work, and on holiday: What influences behavioral consistency across contexts? Frontiers in Psychology 9:2447.

Wilson, N.L.W., B.J. Rickard, R. Saputo, and S.-T. Ho. 2017. Food waste: The role of date labels, package size, and product category. Food Quality and Preference 55:35-44.

Yu, Y., and E.C. Jaenicke. 2018. The effect of sell-by dates on purchase volume and food waste. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101879.