2

Health and Well-Being in Diverse Populations: Frameworks and Concepts

Sexual and gender diverse (SGD) people experience the world in different ways than their heterosexual, monosexual, endosexual, or cisgender counterparts. They also have varied experiences both across and within sexual orientation, gender identity, and intersex groups. It cannot be assumed that lesbian and bisexual women face the same environmental and societal challenges, nor can it be assumed that two gay men of different ethnicities and social statuses have similar experiences simply because they share a sexual orientation. An individual’s health and well-being over the life course are determined by a combination of experiences, opportunities, and decisions that are influenced by their social relationships as well as their interactions with institutions and social structures, such as education, health care, government, public safety, housing, immigration, criminal justice, the military, and employment.

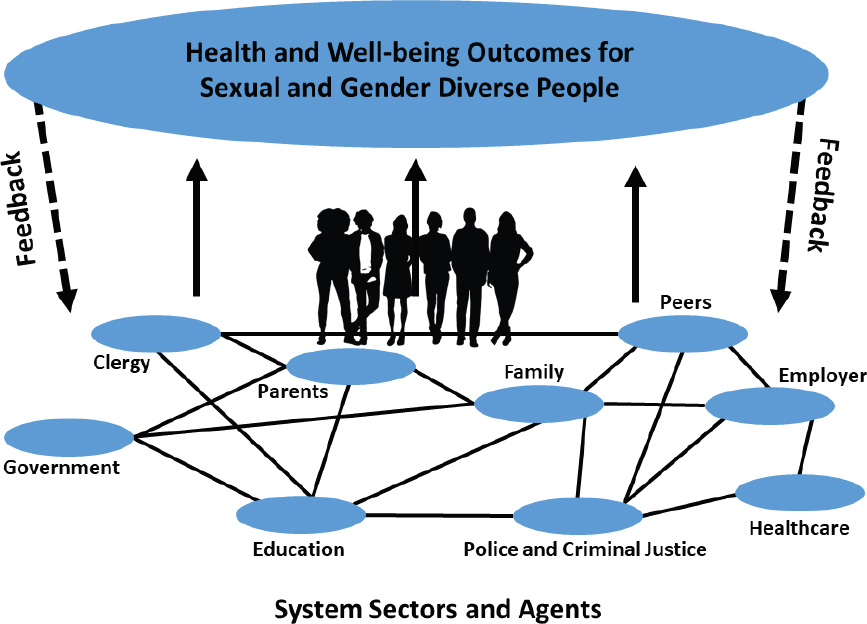

The identities and lived experiences of SGD individuals are complex, multidimensional systems. By applying a complex systems perspective in our work, the committee acknowledges the dynamic nature of human development, individuals’ immediate environments, and the broader contexts in which they live their lives. In a complex system, each element interacts with and provides feedback to others and to the individual, potentially leading to changes in behaviors, roles, and functions that may result in nonlinearity or disproportionality (small effects in one area and large effects in another), novelty (yielding unexpected outcomes or responses), or time discordance (having delayed effects): see Figure 2-1.

This report reflects the committee’s awareness that multiple systems simultaneously affect opportunities and outcomes for SGD communities. The

committee used the following frameworks to organize its thinking around these systems and their complex interactions:

- social ecology—how individuals are embedded in families, communities, societies, and the environment;

- social constructionism—how individuals experience their own lives and identities and the meaning they and others give to experiences and events;

- identity affirmation—how people become aware of, express, and affirm their sexual orientation, gender identity, and other aspects of identity;

- stigma—how dominant cultural beliefs and differences in access to power can lead to labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination for those who do not align with societal norms;

- life course—how experiences from early to late in life accumulate and affect health and well-being at different ages and stages of development; and

- intersectionality—how multiple forms of structural inequality and discrimination, such as racism, sexism, and classism, combine to produce complex, cumulative systems of disadvantage for people who live at the intersections of multiple marginalized groups.

The frameworks are intended to provide readers with a depth of understanding of the influences and dynamics of multiple systems on the health and well-being of sexual and gender diverse people. They are not tools by which to evaluate an individual’s or group’s experiences and identity; rather, the frameworks act as lenses through which one can see how these systems combine to produce novel and nonlinear outcomes that can affect an individual’s well-being. Though all the frameworks and concepts are not equally pertinent to the content of this report, understanding this scholarly landscape allows the committee to situate the specific issues addressed throughout this report in broader theoretical contexts.

SOCIAL ECOLOGY

The social ecological approach enhances understanding of how human well-being is shaped by multiple interacting levels of influence between individuals, their immediate environment, and larger contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner and Ceci, 1994). These levels are interconnected, reciprocal, and complex, and they include

- individual-level factors, such as age, race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, intersex status, and genetics;

- interpersonal-level factors such as relationships with partners, family members, friends, and peers;

- community-level factors such as schools, workplaces, community spaces, and religious institutions;

- societal-level factors such as laws, policies, and cultural and social norms; and

- environmental-level factors such as the natural environment and large-scale historical trends.

In this approach, people are embedded in families, communities, societies, and broader environments, and the interplay across and between these factors influences the health and well-being of individuals and populations (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020 [hereafter, Secretary’s Advisory Committee], 2010). At each level, SGD populations experience unique stressors and sources of resilience related to sexual orientation, gender identity, and intersex status. This constellation of stressors and resources shapes their well-being across all domains, such as education, economics, relationships, and health. The social ecology model also recognizes that the experiences of SGD populations at each level vary as a function of gender, race, ethnicity, and other intersecting aspects of identity.

The social ecology approach is important in understanding patterns and etiology of risk and resilience, and it also offers a framework for developing strategies at multiple levels to support the well-being of SGD populations. There is substantial evidence that multilevel interventions have more potential for success than those that concentrate only on a single level (Sallis, Owen, and Fisher, 2008; Secretary’s Advisory Committee, 2010). The Secretary’s Advisory Committee 2010 report for Healthy People 2020 states, “Motivating people to change health-related behaviors when social and physical environments are not supportive often leads to weak, temporary change” (p. 29). Thus, if SGD populations are at greater risk for a behavior such as substance use, policies or interventions to address this disparity are more likely to be successful if they address not only individual behavior but also factors at interpersonal (e.g., family rejection), community (e.g., bullying in schools), and societal (e.g., employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity) levels. The social ecology approach is also useful for synthesizing diverse sources of data and research methods to understand how multiple levels of influence shape the well-being of SGD populations across different domains.

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM

Social forces influence people’s shared understandings of reality. The theoretical framework called social constructionism examines the ways in which individuals, groups, cultures, and societies perceive social issues and problems. Social constructionism is often used to explore the influences of culture, society, and history on the ways in which individuals experience their own lives and the meanings that they give to these experiences. This perspective also suggests that facts and knowledge must be understood in the context of the particular culture or society that generated them, and it maintains that knowledge is influenced by and made tangible through social interactions.

A key tenet of social constructionism is the effect that socially constructed concepts and ideas have on individuals and the role that those in power have in constructing ideas, concepts, and even realities. For example, instead of focusing solely on the effect of a disease on people’s bodies, social constructionism emphasizes the meaning that the illness has for the affected individuals and for those around them and how that shapes their experiences (Lupton, 2000). Likewise, it emphasizes the role that those in power have to construct how society, as a whole, understands diseases and illnesses and the context that is applied to certain groups. As such, social constructionism is frequently used as a framework to explain why some health issues, such as HIV/AIDS, obesity, and cancer, are stigmatized, and to examine societal responses to those stigmatized health issues. Beyond

the objective condition of a disease state, social understandings, reactions, and beliefs about a disease shape how a person understands or experiences the disease.

Symbols and shared group meanings also play a central role in conceptualizations of individual identity and social and group interactions. The meanings behind the power and privileges given to traits, behaviors, and identities attributed to particular groups are constructed aspects of culture that can be questioned. For example, understanding concepts such as “race”; racial categories; and privileges associated with skin complexion, hair color, facial features, and nation of origin as culturally constructed illuminates the ways that race is not a biological category but rather a social construct. Similarly, feminist scholars have questioned the meanings and privileges associated with gender roles in different cultures around the world and throughout history.

The approach of social constructionism highlights social and cultural forces that affect how gender and sexuality are perceived by different individuals, groups, and societies. This perspective may illuminate the effect that social issues and problems have on specific groups, particularly those most marginalized. For example, research on health and wellness among gay and bisexual men often describes them using the term “men who have sex with men.” A social constructionist approach reveals that the emphasis on their behavior, which is typically described as “risky,” erases the sexualities and identities of these men. Similarly, social constructionism is an important lens for understanding limits to the universal applicability of specific terms used to define and categorize sexual and gender diversity, which can vary within and between communities, societies, geographies, and time periods; it can help people better understand the power, privileges, and resources to which these groups have access.

STIGMA

Since Goffman’s pioneering book, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (1963), social scientists have sought to identify the causes and consequences of stigma. Many definitions of stigma have been offered, which has led to some confusion about the meaning of this term. In part to address this confusion, Link and Phelan (2001, p. 367) advanced a highly influential conceptualization of stigma, which defines stigma as follows:

In our conceptualization, stigma exists when the following interrelated components converge. In the first component, people distinguish and label human differences. In the second, dominant cultural beliefs link labeled persons to undesirable characteristics—to negative stereotypes. In the

third, labeled persons are placed in distinct categories so as to accomplish some degree of separation of “us” from “them.” In the fourth, labeled persons experience status loss and discrimination that lead to unequal outcomes. Stigmatization is entirely contingent on access to social, economic and political power that allows the identification of differentness, the construction of stereotypes, the separation of labeled persons into distinct categories and the full execution of disapproval, rejection, exclusion and discrimination. Thus, we apply the term stigma when elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss and discrimination co-occur in a power situation that allows them to unfold.

There are several important aspects to the conceptualization of stigma. First, it is important to distinguish between the related, though distinct, concepts of stigma and discrimination. While discrimination is a constitutive feature of stigma—in fact, the term stigma “cannot hold the meaning we commonly assign to it” when discrimination is left out (Link and Phelan, 2001, p. 370)—stigma is broader because it incorporates several other elements in addition to discrimination, such as labeling and stereotyping (Phelan, Link, and Dovidio, 2008). Moreover, stigma produces negative consequences even in the absence of discrimination and even without another person present in the immediate situation (Link and Phelan, 2001; Major and O’Brien, 2005). Thus, the concept of stigma captures numerous pathways that produce disadvantage outside of discriminatory action.

Second, stigma is dependent on power. Link and Phelan’s (2001) definition illuminates the idea that power is present whenever stigmatization occurs. Power is necessary for people who stigmatize others (i.e., “stigmatizers”) to achieve the ends they desire. As summarized by Phelan and colleagues (2008), the ends that are attained by stigmatization include “keeping people down” (exploitation/dominance), “keeping people in” (norm enforcement), and “keeping people away” (disease avoidance). In each instance, the dominant group gets something they want by stigmatizing others—that is, there are motives or interests that underlie and perpetuate stigmatization (Link and Phelan, 2001).

Stigma-driven motives are exercised through individual, interpersonal, and structural mechanisms, each of which contributes to negative outcomes for the stigmatized (Hatzenbuehler, 2016; Link and Phelan, 2001). Individual forms of stigma refer to the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes in which individuals engage in response to stigma, such as (1) identity concealment, or hiding aspects of one’s stigmatized status/condition/identity to avoid rejection and discrimination (e.g., Pachankis, 2007); (2) self-stigmatization, or the internalization of negative societal views about one’s own group (Corrigan, Sokol, and Rüsch, 2013); and (3) rejection sensitivity, or the tendency to anxiously expect, and readily

perceive, rejection based on one’s stigmatized status/identity/condition (e.g., Mendoza-Denton et al., 2003).

In contrast, interpersonal stigma refers to interactional processes that occur between stigmatized and non-stigmatized people. These interpersonal processes include both intentional, overt actions (e.g., bias-based hate crimes; Herek, 2009), as well as unintentional, covert actions (e.g., micro-aggressions; Sue et al., 2007). Structural stigma, which refers to processes that occur above the individual and interpersonal levels, is defined as “societal-level conditions, cultural norms, and institutional policies that constrain the opportunities, resources, and well-being of the stigmatized” (Hatzenbuehler and Link, 2014, p. 2). Examples include laws and policies that disadvantage specific groups, such as marriage bans for same-sex couples or differential sentencing for crack as opposed to powdered cocaine for racial and ethnic minorities.

INTERSECTIONALITY

Intersectionality is a term that describes how categories such as race, class, gender, and sexuality create and maintain forms of structural inequality and discrimination. Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) to describe the experience of living under interlocking systems of oppression—particularly around race, gender, and class—about which she and other Black feminists had theorized. An intersectional lens frames systemic influences in a broad context, emphasizing the complexity and variety of individual experiences in an effort to understand the workings of privilege and power (Tomlinson and Baruch, 2013). Other categories of social identity and vectors of power often examined through an intersectional lens are ethnicity, nationality/migration, ability/disability, and HIV disease status (Crenshaw, 2017).

While many early Black feminist thinkers advanced intersectional analyses of the social location and conditions of Black women, some especially important work was done by the Black lesbian feminists of the Combahee River Collective (CRC) beginning in the 1970s. The CRC used the idea of intersectionality to illustrate how multiple oppressions reinforce each other to create new categories of human suffering (May, 2015; Taylor, 2017). The CRC made it clear that race, class, gender, and sexuality are vectors of power as well as social identity categories. They argued that social categories are not independent and unidirectional; rather, they are co-constitutive and interdependent. The CRC and other scholars also argued that individual social categories reflect larger structural forms of inequality, such as racism, patriarchy, homophobia, and class oppression (Bowleg, 2013).

In her research on intersectionality, feminist Evelyn Nakano Glenn (2002) emphasized how categories of identity are often constructed using opposites and dichotomies rather than integrated and relational terms. She argued that this requires suppressing variability within categories so that dominant characteristics, such as whiteness, maleness, and heterosexuality, are normalized. In other words, white appears raceless, man appears genderless, and heterosexuality appears to be void of sexualization (Glenn, 2002). In this way, the powerful or dominant elements in society are not questioned.

The concept of intersectionality has influenced how scholars, activists, advocates, artists, and policy makers conceptualize individual and group identities, how they craft and sustain political alliances, and how they analyze and address systems that produce and maintain social inequities (May, 2015). It suggests an analytic framework that assists in examining the nature and workings of forms of interlocking structural stigma, inequality, and discrimination. It functions as a heuristic that reveals and highlights specific dynamics that privilege binary distinctions and single-axis thinking (May, 2015). Intersectionality is an approach to inquiry and a way to organize knowledge. For example, Berger and colleagues (2001) suggest that “intersectional stigma” is a complex process by which, in their study, women of color—who are already experiencing race, class, and gender oppression—are also labeled, judged, and given inferior treatment because of their status as drug users, sex workers, or HIV-positive women. For women who are lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex, or otherwise members of SGD communities, discrimination and disadvantage based on sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status may add additional layers of oppression. Writing from an intersectional perspective attends to the complex nature of power and how its intersectional qualities inform the experiences of SGD communities.

IDENTITY AFFIRMATION

The processes by which members of SGD communities come to explore, understand, declare, and affirm aspects of their identities related to sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status are complex. Each aspect of one’s identity has distinct characteristics and follows different developmental pathways; at the same time, however, they are deeply intertwined (Doreleijers and Cohen-Kettenis, 2007). Processes of “coming out” and affirming one’s identity vary widely by factors such as stage of life, family circumstances, and socioeconomic and political influences. There has been a long-standing predominant research focus on adolescence because of the well-documented vulnerabilities of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth (Russell and Fish, 2016) and because individual knowledge and awareness of one’s own sexual orientation, gender identity,

or intersex status often emerges with the biopsychosocial changes associated with puberty (Herdt and McClintock, 2000). Yet many young people are aware of differences in their thoughts and feelings associated with sexuality earlier in childhood, and for many transgender and other gender diverse youth, transgender identity awareness emerges in very early childhood (Levitt and Ippolito, 2014). Both psychosocial and biological factors influence gender identity development, yet most research approaches these areas of influence in isolation, so little is known about the complex dynamics among psychosocial and biological influences (Steensma et al., 2013). In addition, there are diverse expressions of differences in sexual development, which raise a range of developmental questions for how people with intersex characteristics come to understand and express various aspects of their identities (Roen, 2019).

Gender affirmation has been broadly defined as an interpersonal and shared process through which a person’s identity is socially recognized (Sevelius, 2013). More specifically, it refers to the process by which people are affirmed or recognized in their gender identity (Reisner, Radix, and Deutsch, 2016). Gender affirmation can be conceptualized as having four core facets: psychological, social, medical, and legal (Reisner et al., 2016):

- psychological gender affirmation, such as self-actualization and validation;

- social gender affirmation, such as gender roles and use of appropriate names and pronouns that correspond with the person’s gender identity;

- medical gender affirmation, such as use of puberty suppression, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming surgeries; and

- legal gender affirmation, such as nondiscrimination protections and accessibility of legal processes to change names and gender markers on identity documents.

Gender affirmation sometimes, but not always, conforms to binary categories of being female or male. Gender affirmation does not require following a discrete or linear series of “transition” events; on the contrary, it can be conceptualized as an evolving process throughout a person’s life course.

There is no single path to gender affirmation—no one pathway that describes how or when people affirm their gender. For many transgender people, awareness and expression of one’s own gender identity is further complicated by having to affirm that identity in both personal and social contexts. Gender affirmation has thus emerged as an important framework for understanding transgender health.

Increasing evidence suggests that gender affirmation is a key determinant of health and well-being for transgender people. Some transgender individuals do not seek any medical interventions; others use hormones and do not seek surgery, and some undergo surgical interventions. Medical gender affirmation therapies (e.g., hormones and surgical interventions) have been found to improve psychological functioning and quality of life for transgender people (Murad et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2018; Rowniak, Bolt, and Sharifi, 2019; Wernick et al., 2019; White Hughto and Reisner, 2016). Social, psychological, and medical gender affirmation were found to be associated with lower levels of depression and higher self-esteem in a community sample of transgender women (Glynn et al., 2016). There is also evidence supporting gender affirmation as a target of intervention to improve viral suppression for transgender women of color living with HIV (Sevelius et al., 2019). Among Black transgender women with and without HIV infection, gender affirmation has further been associated with increased personal competence and acceptance of self and life (resiliency) and decreased perceived stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Crosby, Salazar, and Hill, 2016). In Black transgender youth, gender affirmation was shown to moderate the association between anticipated stigma and health care avoidance: anticipated stigma around health care treatment and subsequent avoidance decreased for youth who had undergone gender affirmation (Goldenberg et al., 2019). The gender affirmation matrix and its psychological, social, medical, and legal contexts and implications have been useful tools to advance understandings of the health and well-being of sexual and gender diverse people, but additional research utilizing this framework is needed.

LIFE COURSE

A life course perspective offers a framework for understanding how experiences accumulate over the life course, from early through late life, to shape advantage and disadvantage in health and well-being across diverse populations. Some population groups experience more disadvantage than others due to their identities, social locations, or sociohistorical contexts. Social patterns accumulate over time (Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe, 2003) and can be affected by variation in stressors and resources across groups. The life course experiences of SGD populations further vary in relation to such factors as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2016). There is more research on some SGD populations than on others; for example, more studies have focused on gay and lesbian populations than on bisexual, transgender, and intersex populations (Reczek, 2020).

Time and place are central to a life course perspective. Life course experiences and individual development are shaped by historical and geographic

contexts (Hammack et al., 2018). Because sexual and gender diversity is now more openly portrayed in popular culture than in previous eras, and because public attitudes around LGBTQ+ individuals and relationships have shifted, SGD youth may be more likely to come out during adolescence (Floyd and Bakeman, 2006). In the case of intersex people, there have been significant shifts in recent decades in cultural awareness and understanding of differences of sex development, as well as advances in patient-centered medical approaches to supporting the health and well-being of people with intersex traits (Roen, 2019). Individual development and life course experiences also vary geographically—both in terms of rural or urban areas and across states or localities. For example, prior to the nationwide expansion of marriage equality in 2015, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals who lived in states that enacted more supportive policies for SGD populations (e.g., civil union legislation) experienced higher levels of psychological well-being and lower rates of hazardous drinking than those in states with more restrictive policies (Everett, Hatzenbuehler, and Hughes, 2016).

Across the life course, members of SGD populations face many unique stressors in their social environments that are directly attributable to their sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status—a phenomenon called “minority stress” (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003). For many years, few people learned they were intersex or came out as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender before adulthood. In recent years, however, many young people have begun to come out in adolescence. Those who self-identify as LGBTQI+ at a younger age may experience more minority stressors related to their sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status, such as conflict within their families or hostile school environments (Russell and Fish, 2016). In addition, adults who are members of SGD communities may face stigma and discrimination in their social networks, workplaces, and health care settings. Exposure to increased stress can activate biological processes (e.g., cardiovascular arousal), psychosocial processes (e.g., anxiety, depression, sleep problems), and behavioral processes (e.g., substance use, isolation) that take a toll on one’s health and well-being.

Protective or resilience factors over the life course can buffer the effects of stress, reduce stress exposure, and, on their own, contribute to cumulative advantage in well-being. A key concept here is that of “linked lives,” which refers to social connections, particularly close and supportive social relationships. In childhood, parents and families of origin can offer highly salient and important resources that promote well-being. For example, parental rejection is particularly undermining for the well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth (Ryan et al., 2009), while parental support can mitigate stress for children and adolescents at high risk of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity (Thomeer, Paine, and Bryant, 2018). Peer and school ties can be an important resource

through adolescence (Martin-Storey et al., 2015; Watson, Grossman, and Russell, 2019), and intimate partner and other chosen family ties are important throughout the life course (Donnelly, Robinson, and Umberson, 2019).

In contrast to stressors that undermine health and well-being, protective factors can activate biopsychosocial processes that contribute to cumulative advantage in health and well-being over the life course. A life course approach emphasizes the power of social contexts to influence individual development and well-being, but it also emphasizes individual agency in the choices individuals make to shape their life experiences and affect their social contexts.

A life course perspective attends to developmental processes across the entire life course, as well as to variation in development across historical and geographic contexts. Life course experiences spill over from one life stage to the next—a process that results in cumulative advantage or disadvantage over a person’s life (Umberson and Thomeer, 2020). Early life course exposure to discrimination and stigma based on sexual orientation, gender identity, or intersex status can thus have lifelong consequences. For example, substantial empirical research shows that exposure to high levels of stress and adversity in childhood sets in motion distinct developmental changes that can undermine health and well-being years and even decades later (Shonkoff et al., 2012). First, childhood adversity associated with discrimination and stigma may be the beginning of a long process of repeated insults to health and well-being that take place over a period of years. Second, childhood may be a sensitive period in the life course, during which significant stress exposure triggers patterns of heightened psychological and physiological reactivity to stress (e.g., hypervigilance, anxiety, cardiovascular arousal) that are detrimental to health. Thus, early life course experiences can set trajectories of health and well-being into motion that may be exacerbated by subsequent exposures to discrimination or interrupted by subsequent exposures to protective factors.

Little research has been conducted on how outcomes for aging SGD populations differ from those experienced by cisgender and heterosexual populations. Because marriage is associated with improved economic status and better health outcomes (see Chapter 8), it could become increasingly important to health and well-being as aging spouses experience declining health. There is a dearth of research on illness, caregiving, and end-of-life issues among SGD populations. Further study is needed to determine the effects of various experiences on the life course of aging populations and what types of social and economic support would improve outcomes for this population.

SUMMARY

In a complex system, elements interact with and provide feedback to other elements and to the individual at the center of the system, potentially

leading to changes in behaviors, roles, and functions that yield unique effects. By applying a complex systems perspective in this report, the committee acknowledges that an individual’s health and well-being emerge from dynamic interactions involving many subsystems or sectors in society.

Three key components of a complex social system are social ecology (how an individual’s social spheres influence health and well-being), social constructionism (how culture, society, and history influence the ways in which individuals experience life and the meanings they derive from these experiences), and stigma (how dominant cultural beliefs and the distribution of power can lead to labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination). Additional concepts that are particularly relevant to understanding sexual and gender diverse communities are intersectionality (how categories such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic class, and HIV/disease status create and maintain forms of structural inequality and discrimination); identity affirmation (how people affirm their sexual orientation, gender identity, and other aspects of identity); and life course (how experiences over an entire lifetime accumulate and affect health and well-being at different ages and stages of development).

These theories and concepts can serve as lenses through which multidisciplinary forms of research evidence can be interpreted: they are included in this report to provide readers with depth of understanding of these influences and dynamics on the health and well-being of sexual and gender diverse people. In the following chapters, the committee uses these ideas where applicable to inform analyses of various domains of well-being.

REFERENCES

Berger B.E., Ferrans, C.E., and Lashley, F.R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 24, 518–529.

Bowleg, L. (2013). “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles, 68(11-12), 754–767.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Ceci, S.J. (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualized: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101, 568–586.

Brooks, V.R. (1981). Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Corrigan P.W., Sokol, K.A., and Rüsch, N. (2013). The impact of self-stigma and mutual help programs on the quality of life of people with serious mental illnesses. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(1), 1–6.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8. Available: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

Crenshaw, K. (2017). On Intersectionality: Essential Writings. New York: The New Press.

Crosby, R.A., Salazar, L.F., and Hill, B.J. (2016). Gender affirmation and resiliency among Black transgender women with and without HIV infection. Transgender Health, 1(1), 86–93. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29159300.

Donnelly, R., Robinson, B.A., and Umberson, D. (2019). Can spouses buffer the impact of discrimination on depressive symptoms?: An examination of same-sex and different-sex marriages. Society and Mental Health, 9(2), 192–210. doi: 10.1177/2156869318800157.

Doreleijers, T.A., and Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. (2007). Disorders of sex development and gender identity outcome in adolescence and adulthood: Understanding gender identity development and its clinical implications. Pediatric Endocrinology Reviews, 4(4), 343–351.

Elder, G.H., Jr., Johnson, M.K., and Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J.T. Mortimer and M.J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course (pp. 3–19). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Everett, B.G., Hatzenbuehler, M.L., and Hughes, T.L. (2016). The impact of civil union legislation on minority stress, depression, and hazardous drinking in a diverse sample of sexual-minority women: A quasi-natural experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 169, 180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.036.

Floyd, F.J., and Bakeman, R. (2006). Coming-out across the life course: Implications of age and historical context. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(3), 287–296.

Glenn, E.N. (2002). Unequal Freedom: How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Glynn, T.R., Gamarel, K.E., Kahler, C.W., Iwamoto, M., Operario, D., and Nemoto, T. (2016). The role of gender affirmation in psychological well-being among transgender women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 336–344. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27747257.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Goldenberg, T., Jadwin-Cakmak, L., Popoff, E., Reisner, S.L., Campbell, B.A., and Harper, G.W. (2019). Stigma, gender affirmation, and primary healthcare use among Black transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(4), 483–490. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31303554.

Hammack, P.L., Frost, D.M., Meyer, I.H., and Pletta, D.R. (2018). Gay men’s health and identity: Social change and the life course. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 59–74.

Hatzenbuehler, M.L. (2016). Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. American Psychologist, 71(8), 742–751. doi: 10.1037/amp0000068.

Hatzenbuehler, M.L., and Link, B.G. (2014). Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 1–6.

Herdt, G., and McClintock, M. (2000). The magical age of 10. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29(6), 587–606.

Herek, G.M. (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(1), 54–74.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/13128.

Kim, H.-J., and Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I. (2016). Disparities in mental health quality of life between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white LGB midlife and older adults and the influence of lifetime discrimination, social connectedness, socioeconomic status, and perceived stress. Research on Aging, 39(9), 991–1012. doi: 10.1177/0164027516650003.

Levitt, H.M., and Ippolito, M.R. (2014). Being transgender: The experience of transgender identity development. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(12), 1727–1758.

Link, B.G., and Phelan, J.C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385.

Lupton, D. (2000). The social construction of medicine and the body. In G. Albrecht, R. Fitzpatrick, and S. Scrimshaw (Eds.), Handbook of Social Studies in Health and Medicine (pp. 50–63). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing. doi: 10.4135/9781848608412.

Major, B., and O’Brien, L.T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137.

Martin-Storey, A., Cheadle, J.E., Skalamera, J., and Crosnoe, R. (2015). Exploring the social integration of sexual minority youth across high school contexts. Child Development, 86(3), 965–975.

May, V. (2015). Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203141991.

Mendoza-Denton, R., Downey, G., Purdie, V.J., Davis, A., and Pietrzak, J. (2003). Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 896–918.

Meyer, I.H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Murad, M.H., Elamin, M.B., Garcia, M.Z., Mullan, R.J., Murad, A., Erwin, P.J., and Montori, V.M. (2010). Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clinical Endocrinology, 72(2), 214–231. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19473181.

Nguyen, H.B., Chavez, A.M., Lipner, E., Hantsoo, L., Kornfield, S.L., Davies, R.D., and Epperson, C.N. (2018). Gender-affirming hormone use in transgender individuals: Impact on behavioral health and cognition. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(12), 110. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30306351.

Pachankis, J.E. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive–affective–behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 328–345.

Phelan, J., Link, B., and Dovidio, J.F. (2008). Stigma and prejudice: One animal or two? Social Science and Medicine, 67, 358–367.

Reczek, C. (2020). A decade of research on gender and sexual minority families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1).

Reisner, S.L., Radix, A., and Deutsch, M.B. (2016). Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 72(Suppl 3), S235–S242. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27429189.

Roen, K. (2019). Intersex or diverse sex development: Critical review of psychosocial health care research and indications for practice. Journal of Sex Research, 56(4-5), 511–528.

Rowniak, S., Bolt, L., and Sharifi, C. (2019). Effect of cross-sex hormones on the quality of life, depression and anxiety of transgender individuals: A quantitative systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 17(9), 1826–1854. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31021971.

Russell, S.T., and Fish, J. (2016). Mental health in LGBT youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153.

Ryan, C., Huebner, D., Diaz, R.M., and Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352.

Sallis, J.F., Owen, N., and Fisher, E.B. (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B.K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4 (pp. 465–486). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. (2010). Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address Societal Determinants of Health in the U.S. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/SocietalDeterminantsHealth.pdf.

Sevelius, J.M. (2013). Gender affirmation: A framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 675–689. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23729971.

Sevelius, J., Chakravarty, D., Neilands, T.B., Keatley, J., Shade, S.B., Johnson, M.O., Rebchook, G., and HRSA SPNS Transgender Women of Color Study Group. (2019). Evidence for the model of gender affirmation: The role of gender affirmation and healthcare empowerment in viral suppression among transgender women of color living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31144131.

Shonkoff, J.P., Garner, A.S., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Siegel, B.S., Dobbins, M.I., Earls, M.F., Garner, A.S., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., and Wood, D.L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663.

Steensma, T.D., Kreukels, B.P., de Vries, A.L., and Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. (2013). Gender identity development in adolescence. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 288–297.

Sue, D.W., Capodilupo, C.M., Torino, G.C., Bucceri, J.M., Holder, A.M.B., Nadal, K.L., and Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271.

Taylor, K.-Y. (2017). How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Thomeer, M.B., Paine, E.A., and Bryant, C. (2018). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families and health. Sociology Compass, 12, e12552. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12552.

Tomlinson, Y., and Baruch, M. (2013). Framing Questions on Intersectionality. U.S. Human Rights Network. Available: https://ushrnetwork.org/uploads/Resources/framing_questions_on_intersectionality_1.pdf.

Umberson, D., and Thomeer, M.B. (2020). Family matters: Research on family ties and health, 2010 to 2020. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1). doi: 10.1111/jomf.12640.

Watson, R.J., Grossman, A.H., and Russell, S.T. (2019). Sources of social support and mental health among LGB youth. Youth and Society, 51(1), 30–48.

Wernick, J.A., Busa, S., Matouk, K., Nicholson, J., and Janssen, A. (2019). A systematic review of the psychological benefits of gender-affirming surgery. The Urologic Clinics of North America, 46(4), 475–486. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31582022.

White Hughto, J.M., and Reisner, S.L. (2016). A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 21–31. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27595141.