Proceedings of a Workshop

| IN BRIEF | |

|

August 2020 |

Understanding Nursing Home, Hospice, and Palliative Care for Individuals with Later-Stage Dementia

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

On July 7, 2020, the Committee on Developing a Behavioral and Social Science Research Agenda on Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) hosted a public workshop via webcast. This Proceedings of a Workshop–in Brief summarizes the key points made by the workshop participants during the presentations and discussions and is not intended to provide a comprehensive reporting of information shared during the workshop.1 The views summarized here reflect the knowledge and opinions of individual workshop participants and should not be construed as a consensus of workshop participants or the members of the Committee on Developing a Behavioral and Social Science Research Agenda on Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

__________

1Presentations, videos, and other materials from the workshop can be found at https://nationalacademies.org/Alzheimersdecadal.

SETTING THE STAGE

Lis Nielsen, director of the Division of Behavioral and Social Research (BSR) of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), opened the session by describing BSR’s goals and resources for dementia research. BSR adopts a life-course approach to research on the social determinants and developmental origins of aging processes and promotes interventions throughout the life cycle to promote healthy aging. It increasingly focuses on midlife prevention of chronic age-related diseases, including dementia, exploring the malleability of risk and protective mechanisms and the potential to intervene to reset and improve aging trajectories before the onset of decline. BSR supports principle-based behavioral interventions and large-scale pragmatic trials embedded in health systems to optimize dementia care and care coordination. NIA hopes that the committee’s charge to develop a ten-year research agenda in the behavioral and social sciences as it relates to Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias (AD/ADRD) identifies novel opportunities for all behavioral and social science fields to accelerate discoveries in Alzheimer’s disease prevention, behavioral and social pathways to cognitive decline, assessment of early psychological changes, elucidation of causes and consequences of dementia health disparities, identification of resource and data infrastructure needs, and advances in health economics of Alzheimer’s disease.

Howard Kurtzman, deputy chief scientific officer at the American Psychological Association (APA), outlined the goals and resources of the organization’s longstanding Committee on Aging, which calls for greater

![]()

research on dementia from a behavioral and social science perspective. APA’s approach to dementia research has focused on the impact of multi-dimensional diversity on the effectiveness of dementia interventions and services; the nature of caregiving during emergencies, such as pandemics, natural disaster, and climate change; the role of technology in caregiving; the importance of dissemination and implementation research; and the need for research to address non-scientist audiences. He urged the committee to frame research conclusions and recommendations in terms of everyday experiences and actionable strategies that can be shared in conversations with policy makers, practitioners, and the public.

END OF LIFE: HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

Maria Glymour, director of the Doctoral Program of Epidemiology and Translational Science at the University of California, San Francisco, and committee member, introduced a panel of individuals specializing in hospice and palliative care, which discussed aspects of end-of-life care as it relates to care for individuals with advanced dementia. The panel examined this from a variety of perspectives, including the impact of policy, the role and accessibility of palliative care programs, and preparation for end-of-life decisions made by and for people living with dementia.

HISTORY OF DEMENTIA CARE RESEARCH – ADVANCED DEMENTIA

Dementia affects an increasing portion of the aging population, with approximately 1 million individuals currently diagnosed with advanced disease (defined as Global Deterioration Scale Stage 7). Susan Mitchell, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, outlined the past, present, and future of advanced dementia end-of-life research by focusing on three types of investigation: retrospective, prospective, and intervention studies.

Retrospective research for advanced dementia is facilitated by large databases characterizing cohorts and outcomes, which are useful for studying forms of care that are not amenable to randomized trials (e.g., the use of feeding tubes). Through the application of retrospective methods, Mitchell noted that researchers have achieved significant milestones in dementia care, such as the reversal of the U.S. health care system’s longstanding reliance on tube feeding, which retrospective research has shown has “no demonstrable benefits and should not be offered.” During the early 2000s, research expanded into more high-quality prospective studies, such as CASCADE and SPREAD in an effort to understand end-stage dementia in real time. This effort produced major findings that demonstrated the urgent need for work to improve end-stage dementia care.

Mitchell highlighted the following three research findings of prospective studies:

- Family understanding of the poor prognosis of advanced dementia correlated with patients receiving less aggressive care.

- Prognostic tools are ineffective at estimating mortality timelines, and therefore access to palliative care for dementia should not be based on prognosis

- Dementia patients are over-treated with antibiotics and are at increased risk of developing antimicrobial-resistant organisms.

Although identified as critical paths toward better understanding how to care for those with dementia, intervention studies are difficult to conduct with individuals with advanced dementia. Mitchell believes researchers have to negotiate a difficult balance between rigorous study of complex and multi-component interventions and the need for interventions that can be adopted in non-academic, real-world dementia care settings. In addition, they grapple with the definition of primary outcomes. For example, Mitchell highlighted a study that did not produce a statistically meaningful impact on the intended outcome—patient’s preference for palliative care—but did increase the chance that a patient with this preference completed an advance care directive. More work might bridge the gap between clinical trials and real-world care settings by developing embedded pragmatic trials that are able to achieve fidelity to intended interventions. She concluded that the next steps for advanced dementia care research include refining the infrastructure for clinical trials (e.g., NIH IMPACT Collaboratory) and then using this infrastructure to explain and reduce disparities in treatments and care and to identify the impact of new health care structures and policies.

POLICY LANDSCAPE FOR END-OF-LIFE DEMENTIA CARE

David Stevenson, professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, explained that the existing public policy framework has the potential to compromise the quality of end-of-life care for people living with AD/ADRD. This framework effectively discourages implementation of the insights gained from research on AD/ADRD, resulting in excessive hospitalizations and burdensome transitions that do not align with individual preferences. Stevenson outlined some of the most significant policy challenges that researchers and advocates might focus on changing, including Medicare hospice benefit limitations, inadequate coverage of long-term services and supports (LTSS), and fragmented end-of-life service delivery.

Medicare hospice benefits are a particularly poor fit for the needs of people living with AD/ADRD. Stevenson noted that hospice is a primary source of palliative care for Medicare beneficiaries, but its prognosis requirement (less than 6 months’ life expectancy) may deter entry for many patients with AD/ADRD who have more uncertain prognoses. In addition, existing reimbursement policies create an artificial division between a Medicare-designated skilled nursing facility (SNF) and hospice benefits, which forces families to choose between rehabilitation and comfort care following hospital care, and incentivizes skilled nursing facility care for patients and providers even though the patient may be clinically more appropriate for hospice care.

Stevenson continued that most people living with AD/ADRD will require long-term services and supports before and alongside end-of-life care, but universal coverage for the former is not available in the United States. Although private insurance for LTSS for end-of-life care is available for purchase, less than 10 percent of individuals over age 65 have long-term services and supports coverage and “particularly in the last decade or so, few new policies have been purchased.” The implications of this gap are especially severe for people dealing with AD/ADRD, Stevenson noted, because they must rely on unpaid care by family (i.e., informal care); out-of-pocket payments; and Medicaid, which pays for only a small portion of nursing home and/or home care costs (Kelly et al., 2020).

Stevenson highlighted the impact of fragmented financing for services at the end of life on care quality and systemic challenges such as racial/ethnic disparities in the care beneficiaries receive. The reimbursement for services provided to people with dementia is fragmented by payer type and benefit (e.g., Medicare Parts A and B, Medicare skilled nursing facility and home health, Medicare hospice, Medicaid/out-of-pocket) and by provider type or setting (e.g., physician, hospital, nursing home, home health, hospice). In addition to Medicare’s lack of coverage for LTSS, Stevenson noted that there are few incentives to coordinate across care settings and that these payment silos can create higher costs and worse outcomes for those living with AD/ADRD. Stevenson emphasized the importance of integrated care in such cases, given patients’ complex and interconnected medical, social, and supportive care service needs. He believes further research is warranted on such topics as (1) the interaction between Medicare and Medicaid services for patients who are dual eligible; (2) end-of-life care quality in nursing homes; (3) expanded access to palliative care outside of hospice; and (4) the advantages and disadvantages of enrolling in Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans and other integrated financing and delivery models.

CLINICIAN PERSPECTIVE ON HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

Nathan Gray, assistant professor at Duke University School of Medicine and staff physician for Duke University Health System, outlined how these insufficiencies are amplified at the end-of-life when mobility issues complicate access to supplemental support (e.g., adult daycare, clinic-based primary care, specialty geriatrics support), and when escalating physical needs, symptom burden, and behavior disturbances challenge in-home care. In his experience working with Duke University’s palliative care program, Gray has observed that palliative care programs for people affected by AD/ADRD (e.g., hospice) do not have the funding to provide adequate care (e.g., Duke’s program). Gray suggested that future research should identify standards for palliative care programs for these patients that can help foster the development of facilities that are specifically suited to this patient population.

Gray observed that the capacity of hospice services to meet the palliative care needs of dementia patients at end-of-life is often complicated by limited caregiver support at home, lack of sufficient staff caregiving hours, limited access to hospital services, and differing ability to access care in nursing homes. However, informal family caregiving is not a viable alternative: Gray’s clinical experience confirms that families caring for their loved one are often ill-equipped to achieve the goal of keeping their family member comfortable at home. Further, Gray noted, many dementia patients do not qualify for Medicaid, while Medicare was not intended to cover long-term care needs, and so families incur out-of-pocket expenses to hire in-home aides.

Although Gray advocated that individuals with advanced dementia should be offered some form of end-of-life palliative care, he reported that his clinical experience has found that hospice alternatives vary widely across the country and few provide home-based aide services. Non-hospice palliative care programs, such as Duke University’s program, are jeopardized by a lack of reliable funding, and most palliative care programs are funded through patchwork models that do not cover all care needs, Gray noted. He argued that palliative care programs require a stronger reimbursement structure and the resources to provide home health aide hours, 24/7 crisis triage, in-home primary care, caregiver counseling, and transportation for specialty services.

Gray emphasized that the “dementia care field should shift from a one-size-fits-all hospice model toward graduated need-based interventions.” Elaborating on this, he emphasized that to achieve this goal, Gray suggested, researchers should focus on in-home interventions for patients—to determine the best strategies for goal-concordant palliative care—and should investigate the comparative effectiveness of various financing methods on access, quality, and cost of care. Gray noted that this research—particularly cost analyses of utilization and expenditures for in-home support—might bolster public policy arguments for expanded palliative services for individuals with advanced dementia. Finally, Gray stated that researchers should work on developing disease-specific quality metrics to be used in oversight, accreditation, and care improvement for community-based palliative care.

RESEARCH PRIORITIES OF PEOPLE LIVING WITH DEMENTIA

Individuals diagnosed with dementia can help direct their own care by creating a roadmap of their end-of-life preferences for family and care providers to follow, explained Cynthia Huling Hummel, member of the Advisory Panel to the committee who served as a discussant for this panel. She noted that signing a care directive does not guarantee that specific types of end-of-life care will be provided. Laws and practice guidelines regarding end-of-life care differ by state and care facility and are often not well-defined or well-communicated to people living with AD/ADRD. Huling Hummel suggested that research could help ameliorate this situation by identifying effective ways for those affected by AD/ADRD to navigate this difficult landscape. “Care partner” is the preferred term in many advocates instead of “caregiver” due to negative connotations for “giving” care instead of working as a team or partnership with the family and community.

Huling Hummel highlighted the case of directives for voluntarily stopping eating and drinking, which many care facilities do not honor and some states actually prohibit. Care facilities often continue to offer patients food and water, putting residents into a situation where they need to willfully refrain from eating or drinking each time. The challenge with this approach, as Huling Hummel noted, is that “most of us with Alzheimer’s or another dementia will not have the capacity to stop eating or drinking on our own.” Therefore, the question becomes whether the state, the care facility, and the family should honor the wishes of the “present” self, who is creating the directive, or the behavior of the “future” self, who may continue to accept food. One tool to assist families in making these choices is the resource “What If I Had Dementia?” from the Health Directive for Dementia (2017). This resource allows individuals diagnosed with dementia to select options that best fit their preferred care at each disease stage.

Huling Hummel noted that physician-assisted suicide is another choice denied to many dementia patients. Even in the Netherlands, where physician-assisted suicide was legalized in 2002, individuals in the advanced stages of dementia were banned from seeking physician-assisted suicide until 2020. This delay stemmed from concerns about the competency of people affected by AD/ADRD to make their own decisions at the end of life. This competency issue is why physician-assisted suicide for such cases is also illegal in the United States. Huling Hummel finished by highlighting two research opportunities that can address obstacles to honoring end-of-life decisions and ensure that individuals living with dementia receive the best goal-oriented care possible: (1) identify what information and resources are most helpful to people living with AD/ADRD as they make their decisions about the end of life and (2) determine how differing state rules about dementia and voluntary cessation of eating and drinking can be better communicated to people living with dementia and their families so that they can better plan, communicate, and implement end-of-life preferences.

MAKING HEALTH SYSTEMS RESPONSIVE TO DEMENTIA

David Reuben, director, Multicampus Program in Geriatrics Medicine and Gerontology and chief, Division of Geriatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and committee member introduced a panel on making health systems responsive to dementia. This panel of specialists who advocate for better care for

people living with AD/ADRD discussed the status of various approaches to improving the current care system, including philanthropic, educational, and caregiver perspectives.

AGE-FRIENDLY HEALTH SYSTEMS

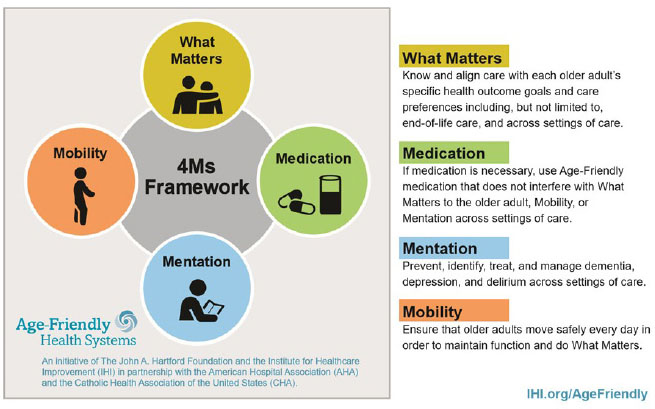

Age-Friendly Health Systems, an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthy Improvement in partnership with other large care organizations, seeks to build a health systems movement that makes age-friendly care the standard for all older adult care. Rani Snyder, vice president for program at The John A. Hartford Foundation, defined age-friendly care as care that is “guided by an essential set of evidence-based practices, causes no harm, and is consistent with what matters to the older adult and their family.”

Evidence-based geriatrics models are not reliably implemented because of difficulties in dissemination, scaling, and reproduction in care settings with limited resources; implementation is also hindered by a lack of translation across care settings. The Age-Friendly Health System team synthesized several models into a single model (known as the 4Ms, see Figure 1) to help all care facilities achieve an age-friendly approach. Although developed for older adults, the model can be applied to younger people, such as early onset dementia patients, who would benefit from the program. As Snyder put it, “Much like geriatric care is best care for all, age-friendly care is best care for all.”

Source: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

The 4M framework prioritizes older adults’ unique definitions of what matters to them—which is shaped by background, ethnic position, preferences for their family, and more—as the guiding principle of care decisions. It identifies three synergistic parameters of care that should align with “what matters” in a way that reduces implementation and measurement burden and can be applied in multiple care settings. Snyder explained that although this model applies broadly to aging, it is highly applicable to dementia care. Its system-level measures include tracking the number of admissions to long-term care facilities and caregiver strain as well as routine mentation screening and documentation. Snyder reported that the mentation arm of Age-Friendly Health Systems stresses the importance of communicating with patients, even by regularly sharing assessment results.

The Age-Friendly Health Systems program has worked with other health care programs, such as the CVS Minute Clinics and Health Resources and Services Administration Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program, to integrate testing and care for people living with AD/ADRD into everyday settings. Building on similar connections, Age-Friendly Health Systems has been successfully implemented into care settings across the country, with 912 hospitals, practices, and long-term care facilities recognized in the Age-Friendly Health Systems as of June 2020. Snyder explained that 742 of these practices and long-term care communities are working to become age-friendly sites, and 170 sites have achieved recognition from Age-Friendly Health Systems as “Committed to Care Excellence for Older Adults.” However, she noted, although the uptake of this program is promising, the numbers are not sufficient to reach all people living with AD/ADRD in the United States and much work remains to ensure that all care facilities emphasize age-friendly health care.

POST-ACUTE AND LONG-TERM CARE

The growing numbers of the oldest-old (ages 85+) translates into growing numbers of people with dementia who require post-acute care (PAC). Vincent Mor, professor of health services, policy, and practice and the Florence Price Grant University Professor in the Brown University School of Public Health, noted that the Improving Medicare Post-Acute-Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act of 2014 mandated a new quality measure of “successful community discharge” that reflects the performance of PAC skilled nursing facility care.

However, nursing home admissions of dementia patients can make the “successful community discharge” quality metric difficult to meet. As Mor explained, nursing homes are disincentivized to accept those living with AD/ADRD because they often require longer stays, have a lower likelihood of discharge, require more staff time to manage clinical and behavioral complexities, and use fewer therapy hours—thus generating less revenue per bed. Upon discharge from the hospital to a designated skilled nursing facility, new people living with AD/ADRD in post-acute -care whose behavioral problems exceed the skilled nursing facility’s capacity are at high risk of rehospitalization, being transferred to another nursing home, or “getting stuck” in long-term care. In fact, Mor said incongruously, the IMPACT Act may have made care systems less accessible and navigable to people living with AD/ADRD.

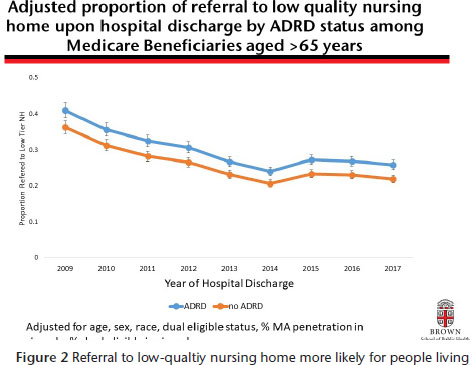

Because little is known about post-acute-care outcomes (such as returning to and staying at home post-discharge) for people with AD/ADRD who enter skilled nursing facilities, Mor and colleagues designed a study to characterize the post-acute care experience of Medicare beneficiaries with dementia. The study examines trends using Medicare claims data and tracks the quality of facilities people living with AD/ADRD and other new post-acute-care cases, entered, their likelihood of rehospitalization, and permanent residence in an long term care facility between January 2007 and September 2015. The investigators reported that there was a 2 percent average annual increase over this period in the proportion of traditional Medicare beneficiaries with dementia who were successfully discharged from the skilled nursing facility to the community, compared with a 1 percent average annual increase for those without dementia. The proportion of beneficiaries who became long-stay (still in a skilled nursing facility after 90 days of entering), who died in the skilled nursing facility, or were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge decreased statistically significantly among all beneficiaries, but disparities remained between those with and without dementia. Furthermore, Mor reported that even adjusting for other factors, people living with dementia entered lower quality nursing homes (see Figure 2).

Source: Mor presentation, 2019.

Mor summarized the finding by noting that Medicare’s Hospital Readmission Reduction Program and its resulting readmission penalties stimulated “major reduction in re-hospitalizations that affected ADRD and non-ADRD post-acute care users equally.” He noted that improvements in successful discharge were dramatic and may explain the ongoing decline in the numbers of long-stay nursing home patients. However, Mor stressed that the disparities between dementia and non-dementia patients persist despite these improvements. He noted that the observed trends will continue to change with the growing aging population and will adjust to the changing composition of populations in nursing homes, which will have lasting implications.

CARE PARTNER PERSPECTIVE

Often, family members will become family caregivers and advocate on behalf of their loved one. Marie Israelite, director of Victim Services at the Human Trafficking Institute and advisory panel member, offered her perspective as a dementia care partner for her mother and summarized the policy work she has undertaken in this capacity. Israelite became invested in dementia policy when she began to care for her mother, who was diagnosed with AD. Israelite stressed the importance of remembering that many traits besides AD define her mother as an individual, marking this holistic view of the person and these traits are important in defining what constitutes good dementia care. For example, Israelite explained that for her mother, quality of life includes having meaning and purpose, being helpful, having connections to community and family, feeling strong, having respect, being heard, and being able to spend time in nature. This whole-person perspective, Israelite stressed, is critical for both researchers studying programs and to deliver successful care.

Israelite praised Snyder’s presentation for its focus on what is important to the individual being treated. She further praised the goal-concordant care outlined in the Age-Friendly Health Systems approach, in particular its emphasis on wellness—which relate to many of the quality of life criteria identified by her mother. Israelite suggested that the Age-Friendly Health System advisory group should include older adults, people living with AD/ADRD, and their caregivers to offer a well-rounded care perspective. These individuals provide the perspective of lived experience, which is critical to shaping advances in the field. Israelite emphasized the importance of Mor’s findings that nursing homes and long-term care facilities are disincentivized to accept people living with dementia and, as a result, many live in lower quality nursing homes—which has a negative impact on their quality of life and that of their caregivers.

Israelite concluded with a review of how cultural and experiential variables can impact an individual’s experience with dementia, using the influence of trauma in childhood or early life as an example. Israelite cited the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, which showed that greater than 60 percent of adults had experienced at least one ACE—experiences like abuse or neglect, witnessing domestic violence, mental illness of a household member—and that 1 in 6 adults had experienced four or more. A recent Japanese study, Israelite noted, suggested that individuals with more ACEs were at increased risk of developing dementia. Further, patients with ACEs may revert to trauma reactions in moments of uncertainty or extreme stress. Israelite relayed that “in moments of uncertainty or extreme stress,” her mother—who experienced childhood trauma—"reverts to trauma reactions … and what she is able to access of her executive functions and skills declines.” In these moments, her mother does not feel safe. To complement the continued documentation of trauma experiences in early life among U.S. citizens, Israelite encouraged future work to identify interventions that are effective and ensure that the dementia patient feels physically, emotionally, and psychologically safe.

POSSIBLE FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR CREATING GOAL-CONCORDANT CARE

In a final discussion, many workshop attendees deliberated on the merits of an interconnected, coordinated health system for treating people living with AD/ADRD. As Mor observed, even centrally governed health care systems typically divide care for dementia patients across multiple practitioners, including a primary care physician, gerontologist, neurologist, and others. The challenge arises, Terrie Moffitt suggested, when these practitioners do not communicate effectively—for example, leaving patients to carry their medical records between offices rather than adopting a patient-centered model in which care automatically “follows the person.”

REFERENCES

Kelly, A., McGarry, K., Bollens-Lund, E., Rahman, O., Husain, M., Ferreira, K., and Skinner, J. (2020). Residential setting and the cumulative financial burden of dementia in the 7 years before death. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 68(6), 1319–1324. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16414.

Mor, V. (unpublished). Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Treatment and Outcomes in America: Changing Policies and Systems, P01AG027296.

COMMITTEE ON THE DECADAL SURVEY OF BEHAVIORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH ON ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE AND ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE-RELATED DEMENTIAS

Patricia (Tia) Powell(Chair), Albert Einstein College of Medicine; Karen S. Cook(Vice Chair), Stanford University; Margarita Alegria, Harvard University; Deborah Blacker, Harvard University; Maria Glymour, University of California, San Francisco; Roee Gutman, Brown University; Mark D. Hayward, University of Texas at Austin; Ruth Katz, LeadingAge; Spero M. Manson, University of Colorado, Denver; Terrie E. Moffitt, King's College, London; Vincent Mor, Brown University; David B. Reuben, University of California, Los Angeles; Roland J. Thorpe, Jr., Johns Hopkins University; Rachel M. Werner, University of Pennsylvania; Kristine Yaffe, University of California, San Francisco; and Julie Zissimopoulos, University of Southern Cali-fornia; Molly Checksfieldstudy director; Tina Winters, associate program officer.

DISCLAIMER: This Proceeding of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Rose Li and Associates, Inc, as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual meeting participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all meeting participants; the committee; the Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Preparation of earlier versions by the following individuals is gratefully acknowledged: Rebecca Lazeration, Dana Carluccio, Rose Li, Nancy Tuvesson. The committee was responsible only for organizing the public sessions, identifying the topics, and choosing speakers.

REVIEWERS: To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Vincent Mor, Brown University, and Tracy Lustig, National Academy of Sciences. Kirsten Sampson Snyder, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as review coordinator.

SPONSORS: The workshop was supported by the Division of Behavioral and Social Research of the National Institute on Aging, AARP, the Alzheimer's Association, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, the U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs, the American Psychological Association, and the JPB Foundation.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Understanding Nursing Home, Hospice, and Palliative Care for Individuals with Later Stage Dementia: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief.Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/25902.

Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education

Copyright 2020 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.