6

Risk Communication and Community Engagement

To ensure an effective and equitable national coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination program, the ethical principles, implementation processes, and expected outcomes must be transparently communicated. Those communications also must be easily accessible, given people’s normal sources of information.

In the words of the committee’s Statement of Task the federal government and the state, tribal, local, and territorial (STLT) authorities responsible for COVID-19 vaccine allocation, distribution, and administration must “communicate to the American public [so as] to minimize perceptions of lack of equity.” As noted in Chapter 3, the “[COVID-19 vaccine allocation] framework must not only be equitable, but also be perceived as equitable by audiences who are socioeconomically, culturally, and educationally diverse, and who have distinct historical experiences with the health system.”

To achieve these ends, STLT authorities must engage the diverse communities that they serve, forming partnerships with organizations that can provide the two-way communication channels needed to hear public concerns and deliver messages from trusted sources, and in accessible ways (e.g., with needed ombudspersons, translations, and translators). Such communication addresses the foundational principles of transparency and procedural fairness, supporting and respecting the public in both what is said and how it is said. Without such transparency, vaccination efforts will struggle to deserve, generate, and sustain trust. Chapters 5 and 7 describe some of the potential partners for this mission.

Such communication and engagement must begin immediately. Although it may be natural to wait until allocation and distribution details

have been set, today’s dynamic news and social media environment does not allow any delay. Given the intense public interest in COVID-19 vaccines, if responsible parties are silent, the vacuum will be filled by other less credible sources, some well meaning and some not. As a result, the public will face confusing, inconsistent, and sometimes misleading information. Moreover, STLT authorities and their partners will cede the opportunity to establish themselves as the authoritative sources of reliable information, then have to wrest that status from competitors. As described more fully in Chapter 7, problems can already be seen in the difficulties experienced with clinical trial recruitment, in surveys where many Americans report unwillingness to get vaccinated, and in anecdotal reports of health care professionals who are reluctant as well—absent trustworthy assurances of vaccine safety and efficacy (Callaghan et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2020; Kamisar and Holzberg, 2020; Resnick, 2020). Equitable allocation and distribution of COVID-19 vaccine is impossible unless members of high-priority groups trust the vaccine and the people delivering it (Chastain et al., 2020; Feuerstein et al., 2020).

Thus, coordinated, evidence-based risk communication and community engagement are essential to the COVID-19 vaccination strategies. Those communications must be (1) consistent with the evidence, (2) consistent with one another, (3) responsive to public needs, (4) tested for comprehension by members of target audiences, and (5) delivered by trusted sources through effective channels. Those channels may include national and social media campaigns, news media interviews, health care personnel, and community leaders. Achieving these goals require listening to public concerns, conveying them to STLT authorities, and reporting back the responses. The listening channels may include surveys, social media monitoring, consultation with community partners, and reports from frontline personnel. Thus, risk communication and community engagement provide the “ear to the ground,” informing STLT authorities about success in fulfilling the foundational principles of this framework.

All these efforts depend on having scientifically sound, independently reviewed, candidly reported information about the vaccines and about the allocation, distribution, and administration process. Risk communicators and their community partners must know how safe and effective vaccines were in clinical trials and subsequent use, as captured by rigorous, transparent surveillance programs. They must also know how vaccines have been distributed and how well that reality corresponds to the equitable allocation framework described in this report. The collection and analysis of that information must be an integral part of vaccination planning. It must include scientists independent of government and firms with commercial interests. Those scientists must represent the diverse communities that are asked to put their faith in the process, including scientists from minority-serving academic institutions.

SCIENTIFIC FOUNDATIONS

These efforts should be grounded in scientific knowledge of risk communication and community engagement. Summaries of that research, as applied to related topics, can be found in many prior National Academies reports, including Improving Risk Communication (NRC, 1989), Understanding Risk (NRC, 1996), Toward Environmental Justice (IOM, 1999), Characterizing and Communicating Uncertainty in the Assessment of Benefits and Risks of Pharmaceutical Products (IOM, 2014), Potential Risks and Benefits of Gain-of-Function Research (IOM and NRC, 2015), Building Communication Capacity to Counter Infectious Disease Threats (NASEM, 2017), and special issues of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on the science of science communication (Bruine de Bruin and Bostrom, 2013; Fischhoff, 2013, 2019; Fischhoff and Davis, 2014). The 2008 National Academies report Public Participation in Environmental Assessment and Decision Making summarizes research on community engagement, with applications to the related domain of environment. The 1999 Institute of Medicine report Toward Environmental Justice devotes two of its three key principles to community engagement with affected populations and risk communication of findings to all stakeholders.

RISK COMMUNICATION

The discipline of risk communication involves an iterative process with four steps (Fischhoff, 2013, 2019; Fischhoff and Davis, 2014):

- Summarize the evidence relevant to the decisions that members of the intended audiences face;

- Describe their current beliefs;

- Create communications designed to close critical gaps in understanding; and

- Test to ensure that they can make informed choices, and repeat as necessary.

Research following this discipline has addressed many specific topics. These include communicating potentially difficult kinds of information (e.g., very low probabilities, uncertainty, exponential transmission processes) and reaching audiences with varied backgrounds (Bruine de Bruin and Bostrom, 2013; Peters, 2020; Schwartz and Woloshin, 2013).

A guiding principle in the research is that communications must be tested before they are disseminated. This principle reflects a common research finding: People overestimate how well they understand other people’s perspectives and how well they themselves are understood (Nickerson, 1999). As a result, unless messages are tested, audiences can be frustrated

by the failure to tell them what they need to know and misled by saying things that are not interpreted as intended. A simple, fast, inexpensive testing procedure is the think-aloud protocol (Ericsson and Simon, 1980): Ask people drawn from the intended audience to think aloud as they read a draft message, sharing how they interpret it and what impression it creates regarding the people behind it.

To promote equity, communications regarding allocation, distribution, and administration of COVID-19 vaccine must meet both content and process goals.

RISK COMMUNICATION CONTENT GOALS

STLT authorities must communicate their guiding principles clearly enough that members of the public can judge their acceptability. They must also communicate the performance of the process clearly enough so that members of the public can judge how well they have achieved equitable allocation and distribution of safe and effective vaccine. For that to happen, STLT authorities must gather and communicate the relevant information about adverse events. Chapter 5 addresses organizational capabilities relevant to monitoring and evaluation.

STLT authorities must communicate about the vaccines’ safety and effectiveness and about the allocation, distribution, and administration process well enough so that people can decide whether they want them for themselves and their families. These communications include the effects of vaccination on disease transmission, disease severity, health risks, and economic activity—for individuals, groups, communities, and the country as a whole. The goal of these communications is informed judgment, not persuasion, and the intent and success of the vaccination efforts should speak for themselves, when clearly communicated.

When describing the expected outcomes of their vaccination efforts, STLT authorities should indicate how uncertain the estimates are, what is being done to reduce that uncertainty, and when better evidence is likely. For example, initial estimates of risks and benefits will reflect the relatively limited samples and observation periods of the clinical trials. Risk communications must explain those limits and plans for updating them, so that people will not feel deceived when later, better evidence reveals rare side effects or ones that took more time to emerge. The STLT authorities must communicate in ways suited to audiences with different backgrounds and knowledge, enhancing their ability to understand the pandemic as it unfolds and their sense of partnership. In order to achieve these goals, implementers must reflect the diversity of the groups that it serves and engage an array of community partners, so as to secure their communities’ trust, hear their concerns, and address them in culturally appropriate, effective ways. Those partners should

include research and educational institutions dedicated to those communities, including the Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Hispanic Serving Institutions, Tribal Colleges and Universities, and other local organizations with strong community roots. Health care professionals will be a vital link in both communication and engagement and deserve special attention.

Communications about COVID-19 vaccination should be placed in the context of other measures for managing the pandemic, including wearing masks and adhering to the social distancing measures needed to protect those who have not been vaccinated (and perhaps cannot be safely vaccinated) and those for whom the vaccine was not effective.

RISK COMMUNICATION CONTENT

COVID-19 vaccination risk communication efforts will be most efficient by creating and testing message prototypes that can be adapted to specific situations. These messages should be suited both for national distribution and for adaptation to the needs of community partners. These efforts should draw on the results and methods of existing research, paying special attention to the following issues, with particular relevance to COVID-19.

Disease Processes That Can Be Misunderstood Unless Properly Explained

Disease processes that will require clear explanation include how quickly diseases spread, how diseases can be transmitted to distant individuals, how to interpret noisy diagnostic test results, and how even imperfect precautions (e.g., face masks, social distancing, hand washing, vaccines) can combine to provide overall protection.

Equity in Vaccination Efforts Procedures and Performance

STLT authorities will be scrutinized for how they equitably treat people in their COVID-19 vaccination efforts. STLT authorities will need to explain the efforts’ procedures and performance authoritatively—perhaps facing criticism based on incomplete information or political goals, as well as criticism from parties who reject the foundational principles or disagree with the interpretation of the evidence of the vaccination efforts.

Empirical Testing

Communications must be tested for comprehensibility, appropriateness, usefulness, and accessibility. Instructions for simple user testing procedures should be provided to all partners, so that vaccination efforts are not un-

dermined by needless misunderstanding—and so that partners receive the feedback that such testing provides.

Appropriate Tailoring

Messages should be tailored to the needs of diverse populations (e.g., considering native languages, reading levels, potential hesitancy, health beliefs, and historic harms and distrust) and delivered through accessible channels (e.g., for people with limited vision or hearing). Here, too, community partnerships and buy-in will be critical to success.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

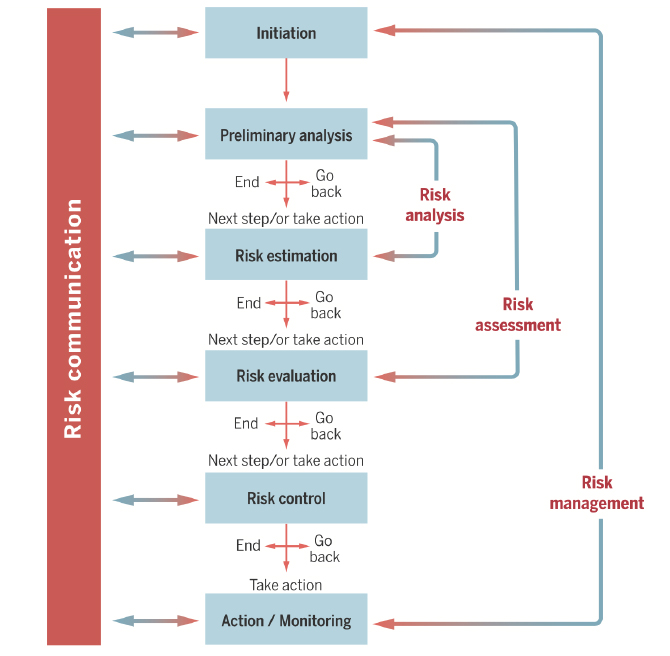

STLT authorities must demonstrate respect for diverse audiences. Providing clear, relevant, accessible information is part of that demonstration. However, people will judge the communication process as well as its content (as captured in this report’s foundational principle of transparency). The widely accepted best practice is continuing two-way communication between the public and experts. That process begins with a project’s initiation, so that it can best address community concerns and establish trusting relations. It continues through execution and monitoring of a project’s performance. Figure 6-1 has one depiction of such a process. Creating the two-way communication channels requires community partners with the knowledge and relationships needed to engage those whose trust and insights are vital to success.

Communication during the early, formative stages increases the chance of meeting the public’s needs. Such communication may also improve success in recruiting members of hesitant populations for vaccine clinical trials. Early community engagement demonstrates that the public is central to conception and has knowledge of key needs and values. Continued engagement during implementation reduces the risk of drifting from the original design in ways that undermine its acceptability. In dynamic environments, such as a pandemic, changes are inevitable as new research, treatments, and problems emerge. As a result, continuous public engagement is needed.

STLT authorities will need a process for coordinating its communications, so that the public is not confused by conflicting messages or deluged by repetitive ones. That coordination must recognize community leaders’ key role in achieving the two-way communication essential to success. Those leaders have a unique ability to translate vaccination efforts into terms meaningful to their communities. They are also uniquely positioned to hear and convey the needs of their communities to STLT authorities. As noted in Chapters 5 and 7, these community leaders and stakeholders include members of professional societies representing minority populations,

SOURCE: Fischhoff, 2015.

community health workers, and leaders from other community-based organizations and non-traditional public health partner organizations.

In summary, public engagement, procedural fairness, and transparency are crucial to the success of a national COVID-19 vaccination program. This committee worked to uphold these principles in its own work, through open public sessions, a public listening session, and a written public comment period (see Appendix A for additional details). Effective risk communication and community engagement will help ensure that the national COVID-19 vaccination program supports STLT authorities, their partners, stakeholders, and the public in respectful, effective ways.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROCESS

Community engagement for COVID-19 vaccination efforts should draw on the extensive science and practice cited throughout this report.

It should pay particular attention to continuous community engagement, engagement across multiple channels, timeliness, and trustworthiness.

Continuous Community Engagement

Community engagement must establish two-way communication channels early enough to provide input for the allocation, distribution, and administration of vaccine and to demonstrate commitment to partnership. It is important to have a strategy for hearing multiple voices.

Engagement Across Multiple Channels

Community engagement must use channels suited to key audiences, including people who cannot attend public meetings (e.g., because they work, live remotely, are incarcerated, or undocumented), who have limited broadband service, who speak languages other than English, or who cannot use written text.

Timeliness

Community engagement must monitor and anticipate the community’s needs. It must provide STLT authorities with information about vaccination efforts, as seen by the people it serves. Contracts with organizations experienced in reaching minority communities can enlist their expert assistance, with needed material support.

Trustworthiness

Community engagement must seek to position STLT authorities as trustworthy sources of information about COVID-19 vaccination. The verbal and nonverbal behavior of the vaccination efforts should be monitored self-critically, in order to avoid violations of trust. It should be ready with counsel when a problem is encountered. Success is, of course, contingent on the actual performance and transparency.

RISK COMMUNICATION AND HEALTH PROMOTION

By fulfilling the duty to inform, the broad risk communication and community engagement efforts described here complement the specific health promotion and demand generation efforts described in the following chapter.

Risk communication and health promotion support one another best when clearly distinguished. Information is trusted less when it appears to

have been presented with persuasive intent. Persuasive communication is more effective when recipients have already absorbed the information needed to understand the science underlying public health recommendations and when trust has already been won. Some people will follow recommendations without background information. Some will want that information in order to feel better about their decision and explain it to themselves and others. Some will need that information in order to accept the legitimacy of the COVID-19 vaccination efforts, particularly given the fractured social environment described in other sections of this report.

Although these efforts are different, their work must be coordinated, drawing on the same facts regarding the disease and vaccination efforts. There may also be cost savings in sharing research resources (e.g., monitoring surveys, communication materials).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Several concerns will be key to the risk communication and community engagement needed to connect vaccination efforts with the public that they must serve. First, they will require great cultural competency in order to reach groups with diverse backgrounds, concerns, and histories with health care systems and research (Taylor and Lurie, 2004). Second, they must provide consistent, authoritative communications from trusted sources, lest the public be justifiably confused by inconsistent, unclear messages from sources whose validity cannot be independently assessed. Third, some features of the COVID-19 vaccination efforts will be unfamiliar and will need special efforts to communicate effectively; those include how it handles heterogeneity within priority groups, how it accommodates uncertainty in transmission patterns, how it addresses legal and treaty rights, and how it responds to changing scientific evidence regarding effectiveness and side effects. Fourth, information about COVID-19 vaccination efforts will have to serve members of the public with different needs, including informing individual patients, engaging community partners, recruiting candidates for research participation (including potentially additional clinical trials), facilitating program administration, coordinating with surveillance programs, supporting health care professionals in their client contacts, and countering misinformation and disinformation. Fifth, some community partners will need material and financial support, provided in ways that do not compromise the independence that affords them the moral authority needed to secure trust. Sixth, these efforts must begin immediately, as perceptions of COVID-19 vaccine are already forming, in ways that might limit successful vaccination.

The entity responsible for the recommended COVID-19 vaccination risk communication and community engagement program must have the

following properties: agility, to respond rapidly to changing circumstances and feedback; competence, to apply relevant risk communication research; diversity, to involve needed perspectives; and independence, to secure trust and provide candid feedback. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services could build on the institutional capabilities of its agencies to implement such a program. Risk communication and community engagement will naturally liaise with partners like those described elsewhere (especially Chapters 5, 7, and 8). Given the difficulty and urgency of the mission, the work should start immediately at a proper scale.

REFERENCES

Bruine de Bruin, W., and A. Bostrom. 2013. Assessing what to address in science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(Suppl 3):14062–14068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212729110.

Callaghan, T., A. Moghtaderi, J. Lueck, P. Hotez, U. Strych, A. Dor, E. Fowler, and M. Motta. 2020. Correlates and disparities of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3667971 (accessed September 21, 2020).

Chastain, D. B., S. P. Osae, A. F. Henao-Martínez, C. Franco-Paredes, J. S. Chastain, and H. N. Young. 2020. Racial disproportionality in COVID clinical trials. The New England Journal of Medicine 383(9):e59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2021971.

Ericsson, K. A., and H. A. Simon. 1980. Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review 87(3):215–251. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.215.

Feuerstein, A., D. Garde, and R. Robbins. 2020. COVID-19 clinical trials are failing to enroll diverse populations, despite awareness efforts. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2020/08/14/covid-19-clinical-trials-are-are-failing-to-enroll-diverse-populations-despite-awareness-efforts (accessed September 21, 2020).

Fischhoff, B. 2013. The sciences of science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(Suppl 3):14033–14039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213273110.

Fischhoff, B. 2015. The realities of risk-cost-benefit analysis. Science 350(6260):aaa6516. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6516.

Fischhoff, B. 2019. Evaluating science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(16):7670–7675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805863115.

Fischhoff, B., and A. L. Davis. 2014. Communicating scientific uncertainty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(Suppl 4):13664–13671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317504111.

Fisher, K. A., S. J. Bloomstone, J. Walder, S. Crawford, H. Fouayzi, and K. M. Mazor. 2020. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: A survey of U.S. adults. Annals of Internal Medicine. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1999. Toward environmental justice: Research, education, and health policy needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014. Characterizing and communicating uncertainty in the assessment of benefits and risks of pharmaceutical products: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM and NRC (National Research Council). 2015. Potential risks and benefits of gain-of-function research: Summary of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kamisar, B., and M. Holzberg. 2020. Poll: Less than half of Americans say they’ll get a coronavirus vaccine. NBC News. August 18, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/poll-less-half-americans-say-they-ll-get-coronavirus-vaccine-n1236971 (accessed September 21, 2020).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Building communication capacity to counter infectious disease threats: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nickerson, R. S. 1999. How we know—and sometimes misjudge—what others know: Imputing one’s own knowledge to others. Psychological Bulletin 125:737–759. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.737.

NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Improving risk communication. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NRC. 1996. Understanding risk: Informing decisions in a democratic society. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Peters, E. 2020. Innumeracy in the wild: Misunderstanding and misusing numbers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Resnick, B. 2020. A third of Americans might refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. How screwed are we? Vox. Updated September 10, 2020. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/21364099/covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-research-herd-immunity (accessed September 21, 2020).

Schwartz, L. M., and S. Woloshin. 2013. The drug facts box: Improving the communication of prescription drug information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110(Suppl 3):14069–14074. doi: 10.1073%2Fpnas.1214646110.

Taylor, S. L., and N. Lurie. 2004. The role of culturally competent communication in reducing ethnic and racial healthcare disparities. American Journal of Managed Care 10(Spec No:Sp1–4).