Setting the Stage for Improving Army Medical Infrastructure Planning

The workshop’s initial sessions addressed the future battlefield environment and potential requirements for the Army’s medical R&D organizations.

PREPARING THE MEDICAL FORCE FOR THE FUTURE FIGHT: GLOBAL INTEGRATION AND THE FUTURE OPERATING ENVIRONMENT

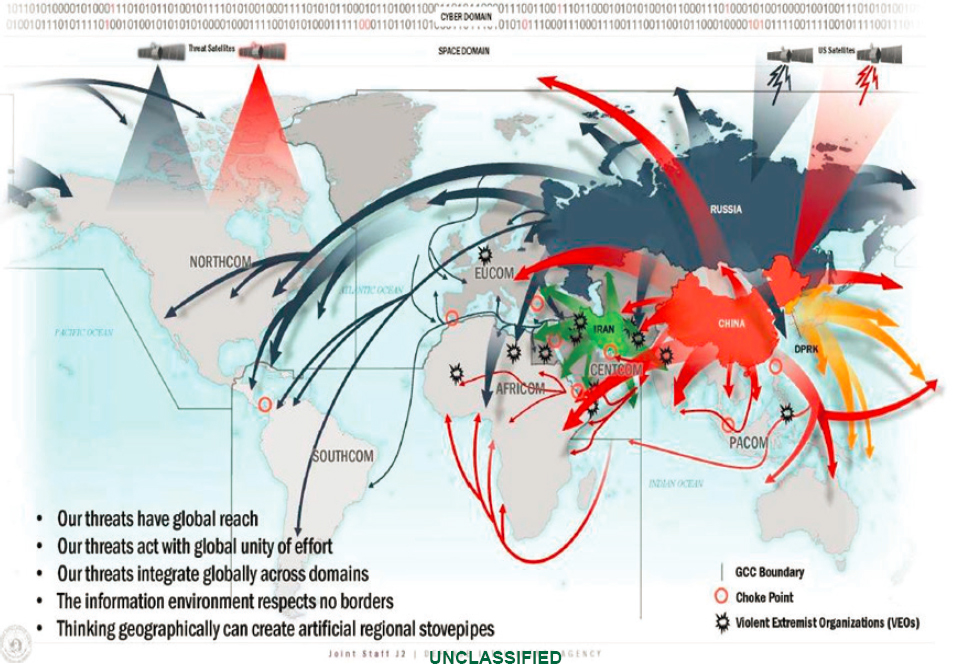

Brigadier General Paul Friedrichs (USAF) outlined the DoD medical community’s goal is to deliver great care. As the Joint Staff Surgeon, Joint Chiefs of Staff, he is looking to the future, and described an array of advanced high-technology medical advancements to consider (e.g., drone use and Internet-connected devices), but was guarded about their use in MDO environments where network capabilities may be compromised. Looking back, he discussed the expeditionary continuum of care, from early ambulance transport to current airlift from the combat zone to modern hospitals. Noting the importance of aligning medical care with threats and the need to treat as close to the front as possible, he highlighted the global reach of the threat environment (Figure 1) and noted that the “information environment respects no borders.”

Friedrichs observed that future casualty-generating threats encompass an array of domains and capabilities, such as cyber; artificial intelligence (AI); chemical-biological-radiological effects; ballistic, hypersonic, directed energy, and autonomous weapons; and robotics. Given

the expected nature of the modern battlefield (mass casualties, fewer targeted improvised explosive attacks, etc.) and the possible lack of air superiority, evacuation (as well as ingress) could be compromised while facing a need to get wounded personnel back into the fight. With these challenges, Friedrichs emphasized the importance of training and basic skills (like tourniquet application) in nonmedical companion soldiers, a focus on triage, and better sensors and noted that much more work is required on implications of chemical-biological attacks. His final messages included the following:

- The need to deliver great care, anytime, anywhere, including mitigation of trauma from evolving threats, plus disease and non-battle injuries;

- Recognizing MDO is an inherently joint concept, which means the involvement of all military services;

- Recognizing the joint casualty stream requires joint solutions; and

- Embracing evolving technology and change, but be wary of chasing it.

With respect to optimal care, Friedrichs stressed effectiveness, which should not be sacrificed for efficiency.

COMBAT CASUALTY—A HISTORY AND FUTURE IMPLICATIONS

Emily Mayhew, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College of London, discussed how the past can enable thinking about the future battlefield. Mayhew focused on World War I (WWI) lessons, particularly serious limb injuries and their relation to the Thomas splint, a device used for stabilizing limb fractures. Using femur fractures as an example, the splint was initially credited for saving lives by reducing the need for amputations, which often resulted in death. However, she found that careful examination showed the fatality drop was due more to innovative stretcher bearers improvising a way to stabilize the femur with carefully placed and folded blankets, creating a simple but effective “splint.” This innovation was amplified by gentle carriage of the victims to aid stations. This capability was practiced in Northern England training camps where respondents practiced in trenches and a war-like environment. This example led to her main theme that development of human capability, not technology, was and remains important, signaling that the medical community has to continue thinking about the training of humans.

Mayhew emphasized that technology offers some of the answers, but the rest come from human capability, giving the example of helicopter

evacuations where success comes not from the helicopter itself, but from the skilled pilots and helicopter occupants who can deal effectively with transporting the wounded to treatment stations. She highlighted another WWI lesson involving battlefield infections, a major consideration for serious wounds, and described how deadly the Western Front was in 1916 without antibiotics. For the present, she noted that infections are still a major concern, even with the development of antibiotics, because resistance to antibiotics continues to develop even as new antibiotics come along. Antibiotic resistance is also driven by geographic area. Mayhew believed by 2035 antimicrobial resistance and the ability to provide antimicrobial therapies will be serious problems for the Army.

PERSPECTIVES ON PROCESS FROM THE ARMY’S COMBAT CASUALTY CARE R&D ORGANIZATION

John Holcomb (Colonel, U.S. Army, retired), Professor of Surgery at the University of Alabama, discussed his perspective as a prior Commander of the U.S. Army Institute for Surgical Research (USAISR). Holcomb has experience in trauma centers, was deployed to combat theaters, led military and civilian trauma training centers, managed technical papers and research grant funding, and is a member of the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) committee. He noted the importance of training and quality of care and highlighted that significant percentages of military and civilian deaths (roughly 15 to 30 percent) could be preventable. Referring to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Army Combat Trauma Care in 2035 workshop,1 he noted that many of the same issues will be present in 2035 as now, including technical development, who is responsible, training, and military versus civilian trauma outcomes. Holcomb asserted that without air superiority, battlefield deaths are likely to go up.

Referring to the DHA instruction on translating DHP research into standards of clinical trauma care across DoD, Holcomb identified the question of how translation into clinical practice will occur, followed by the need to measure the translation, citing numerous challenges such as ownership, metrics and data, prehospital and trauma expertise, R&D, and hospital culture. Regarding processes, he said leadership is most important, not devices or process, and line leaders must be responsible for medical care on the battlefield. With regard to process issues and their procedural details, he said the bottom line is determining how the

___________________

1 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020, Army Combat Trauma Care in 2035: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/25724.

military medical R&D process will improve outcome on the battlefields. Holcomb discussed process issues, including the following:

- Identifying priorities for the battlefield;

- Overemphasizing preclinical research within DoD;

- Being able to respond to new threats;

- Addressing next wars before solving problems of previous wars;

- Coordinating with agencies like FDA, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and other military services;

- Having senior leaders listen to clinical and research leadership; and

- Using new products and devices in routine clinical practice before deployment.

WAR AND INTRA-WAR TRAUMA RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

Holcomb discussed the differences between wartime care, when DoD care and research moves to the battlefield and leads civilian care, and interwar periods, when civilian care and clinical research leads battlefield trauma care. He noted the criticality of funding and that trauma was the leading cause of U.S. deaths in the period 2000-2010 for cumulative ages up to 59, but trauma funding by NIH in 2014 received the least amount for research compared to cancer, heart disease, and HIV-AIDS. To avoid the so-called Walker Dip2—where battlefield improvements in medical care are lost during peacetime and then must be relearned during the next conflict—he believes that DoD should focus on clinical research and translating wartime innovations into civilian standards of care so that these standards can be the starting point for subsequent deployed-military care. This would include stationing large numbers of Level 2 and Level 3 teams at 20-30 high-volume, high-quality civilian academic Level 1 trauma centers. Holcomb asserted that benefits to military personnel at these trauma centers would include routinely caring for very sick patients at those centers and establishing an ongoing research network focused on military-relevant clinical research. Holcomb referred to the Air Force concept of military trauma teams assigned to a large number of academic civilian trauma centers with high volume and high capacity, thus producing a national trauma care system as outlined in the 2016 National Academies report A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero

___________________

2 R.L. Mabry and R. DeLorenzo, 2014, Challenges to improving combat casualty survival on the battlefield, Military Medicine 179(5): 477-482.

Preventable Deaths After Injury.3 Key outcomes of meshing military and civilian trauma centers include the following:

- Measuring clinical research with care to produce deployable expertise,

- Forming and maintaining industry connections,

- Clinical adoption, and

- Knowledgeable leadership.

Holcomb believed a key future organization would include multidisciplinary teams caring for many patients and doing clinical research. The same teams would use the same concepts and products in a clinical setting on the battlefield, benefiting both military and civilian casualties. Deployed teams would be expert clinicians and knowledgeable about the latest care, leading to improved care on the battlefield. Holcomb highlighted major scientific trauma lessons learned over the past two decades in training, systems of care, hemorrhage control, transfusions, orthopedics, neurosurgery, research funding, and leadership. He looked to advances in cell therapy, sepsis, posttraumatic stress disorder, pain control, new transfusion products, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and rehabilitation for the future and emphasized that leaders should be held responsible for potentially preventable deaths.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE DEFENSE HEALTH BOARD AND THE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Clifford Lane, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Deputy Director for Clinical Research and Special Projects, Defense Health Board (DHB) and Chair of the DHB Public Health Subcommittee, described the 2017 DHB report Improving Defense Health Program Medical Research Processes4 and the 2019 DHB findings and recommendations and DHA responses5 outlined in Table 1. The 2017 report was

___________________

3 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016, A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/23511.

4 Defense Health Board, 2017, Improving Defense Health Program Medical Research Processes, Defense Health Headquarters, Falls Church, VA, https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2017/08/08/Improving-Defense-Health-Program-Medical-Research-Process.

5 Defense Health Board, 2019, “Update for Defense Health Board: Improving Defense Health Medical Program Medical Research Processes,” presentation, August 6, Defense Health Headquarters, Falls Church, VA, https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Presentations/2019/08/06/Update-on-Defense-Health-Board-Improving-Defense-HealthProgram-Medical-Research-Processes.

TABLE 1 Overview of Findings and Recommendations of Defense Health Board (DHB) 2017 Report on Improving Defense Health Program Medical Research Processes and 2019 Defense Health Agency (DHA) Responses

| Set | DHB Report Findings and Recommendations | DHA Responses |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Findings:

|

|

Recommendations:

|

Response:

|

|

| 2 |

Findings:

|

|

Recommendations:

|

Response:

|

|

| 3 |

Findings:

|

|

Recommendation:

|

Response:

|

|

| Set | DHB Report Findings and Recommendations | DHA Responses |

|---|---|---|

| 4 |

Findings:

|

|

Recommendations:

|

Response:

|

|

| 5 |

Findings:

|

|

Recommendations:

|

Response:

|

|

| 6 |

Findings:

|

|

Recommendations:

|

Response:

|

|

NOTE: DoD = Department of Defense; IRB = Institutional Review Board; SOP = standard operating procedure.

SOURCE: Clifford Lane, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Defense Health Board, and DHB Public Health Subcommittee, presentation to the workshop.

stimulated by a 2015 request from the Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. The report addressed the following six categories: (1) strategies to improve viability, (2) major challenges initiating research, (3) facilitating initiation and conducting research, (4) improving review processes, (5) cost-effective mechanisms to encourage research, and (6) mechanisms to improve visibility of contributions. A relevant action to this workshop, the DHA organization for 2019 added a deputy assistant director for R&D. Lane attributed lack of progress implementing the recommendations to a lack of commitment at the command level to re-create the historic world-class biomedical research element of DoD (including the Army); further, DHB believed this DoD research element to be severely compromised by a lack of infrastructure and core funding, absence of a career track for officers, and noncompetitive pay for civilians. Lane then highlighted DoD medical-research contributions, such as tourniquets and blood products. On funding, he discussed DHP and congressionally directed medical research funding in 2016 and noted that the individual services, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) also provided funds in 2016 for medical research.

BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES OF INTERAGENCY PARTNERSHIPS

Lane described key research activities of Army and NIAID organizations. Under an Army and NIAID memorandum of agreement, there are collaborations with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), and others. Both the Army and NIAID operate in conjunction with the National Interagency Biodefense Campus (NIBC) and the National Interagency Confederation for Biomedical Research (NICBR). The NIBC is a consortium of several research agencies and institutes with separate and distinct missions and complementary capabilities; it was established in 2002 after the World Trade Center attacks and anthrax letter threats sparked concerns about weapons of mass destruction. The NICBR vision is for research partners to work in synergy to achieve a healthier and more secure nation; the mission is to develop unique knowledge, tools, and products by leveraging advanced technologies and innovative discoveries to secure and defend the health of the American people. Trust and teamwork are integral parts of how NICBR partners understand and respect the differences in each organization. The NICBR is governed by a strategic plan with three elements (research, coordinating bodies, and buildings) and leverages unique resources with its partners for projects, including bio-threat countermeasures, translational research and technology

development, emerging plant pathogens, bio-forensics and threat characterization, advanced environmental microbiology, rapid diagnostics, and advancing regulatory science for medical countermeasures. Lane summarized the NIAID perspective on Army collaboration as a tremendous partnership and a unique confluence of federal agencies; however, lack of combined funding for infrastructure is a challenge. He believed the Army is a valued partner implementing parts of the NIAID research mission, which has been facilitated by overarching agreements that resolve issues like intellectual property and data sharing; however, frequent staff turnover is a challenge.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE ARMY MEDICAL MATERIEL AND MEDICAL RESEARCH COMMANDS

Kenneth Bertram, Clinical Product Development Officer for the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, described a range of advancements beyond body armor to save lives, such as blood component therapy and whole blood, tourniquets, buddy aid and training, and rapid evacuation. He highlighted the value of stopping hemorrhage, the dominant injury among potentially survivable wounded soldiers.

Bertram served as former U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) Principal Assistant for Acquisition, and he highlighted the value of Army medical research, development, and acquisition (RDA). The mission and vision of USAMRMC is to responsively and responsibly create and deliver medical information and products for the warfighting family, and be a trusted partner for leading biomedical research and materiel innovation for global health. The overall thrust is to support the total warfighter life cycle in terms of wellness, performance, enhancement, and protection. He outlined the Army need for dependable investment and control in medical RDA and laboratory infrastructure to enable the soldier and health life cycle, provide for soldier readiness, save lives, and return soldiers to duty. Bertram noted that Army medical RDA is now fractured among a range of organizations (e.g., AFC, DHA, Army Materiel Command [AMC], the general staff, etc.). He asserted that DHA has too many programs and is distracted; DTRA is a failure for the USAMRIID organization.

Medical RDA requirements are driven by the operational Army and DoD needs. However, the requirements process is slow, fights the last war, and fails to see opportunities. Bertram pointed out that the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command (USAMRDC) has many responsibilities, stakeholders, and focus areas, the latter which includes disease threats, chemical and biological threats, environmental hazards, severe battle injuries, hazards (from lasers, blast, noise, etc.), and a range

of stresses. Bertram reviewed the core capabilities and competencies of USAMRDC—basic and applied biomedical research, advanced biomedical development, procurement and fielding (in conjunction with AMC-Medical Logistics Command), medical R&D support functions (contracting, legal), and technology transfer.

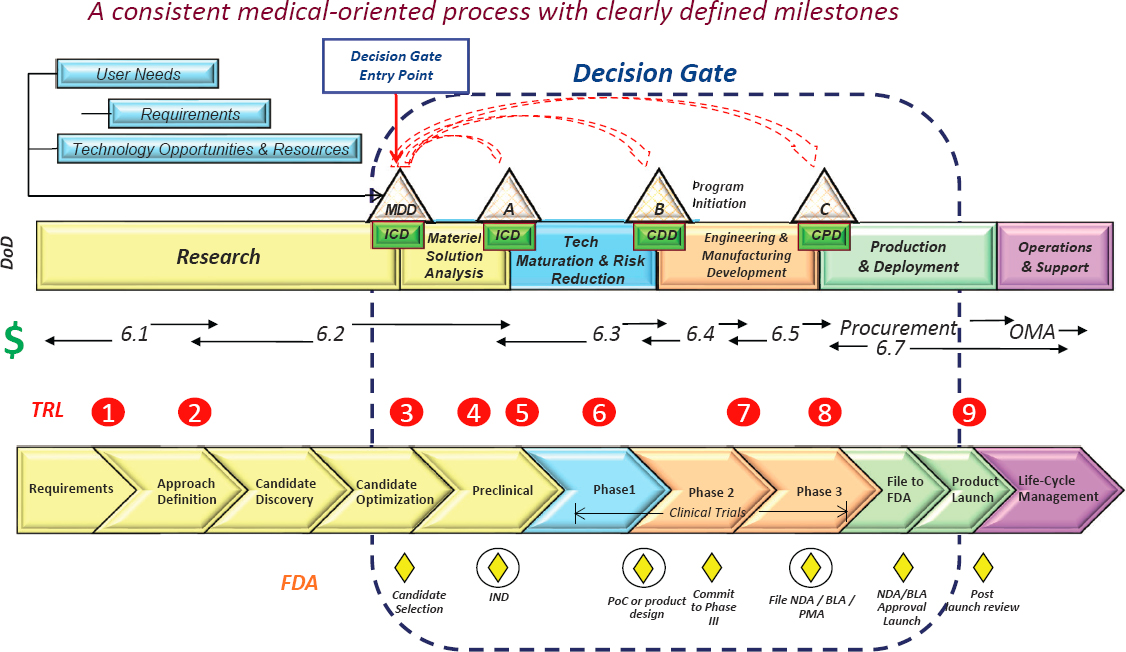

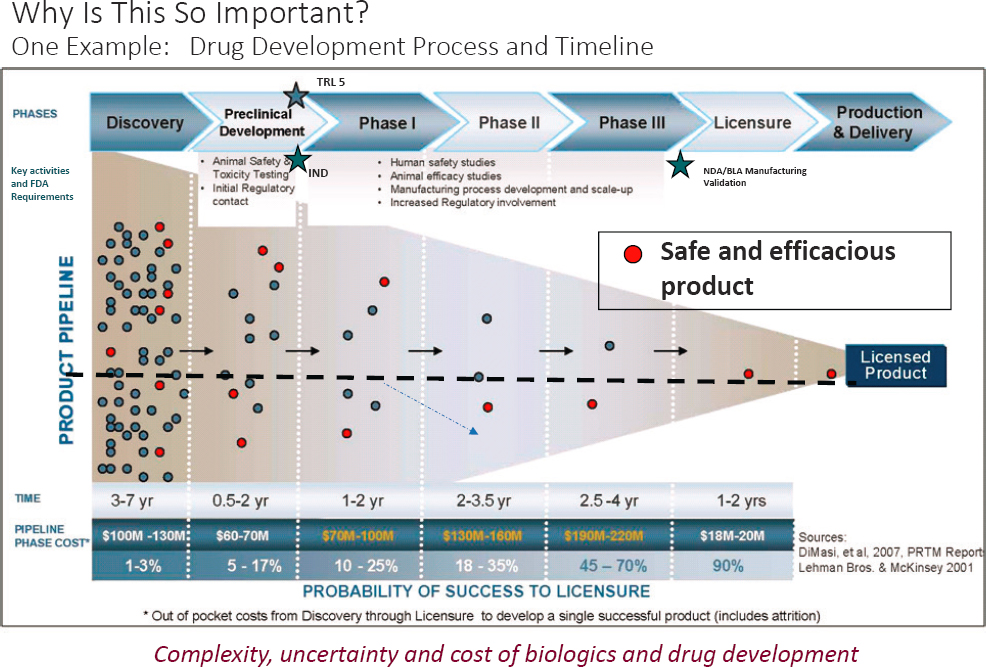

Bertram showed the typical medical acquisition life cycle (Figure 2) from discovery to prototyping, to production and fielding, and sustainment and improvements. Bertram emphasized the essence of the product development model is to pursue what is needed, not what is interesting. His fielding example was the history of tourniquets, which were out of favor. The device was able to save battlefield lives after testing, training, improvements, and proper R&D funding. He noted that the long-term reach of some product developments (6 to 30 years) with future unmanned evacuation options, using drones and ground vehicles as examples. Another example of long-term product development was illustrated with drugs (Figure 3). Many candidates, over many years, funnel down to a single FDA-licensed product. With respect to point-of-injury and prolonged field care, Bertram closed with several time-phased acquisition examples, including delivered (junctional tourniquets), near- to mid-term development (wound stasis foam), and far-term (site-specific clotting technology and nanotechnology trauma drug delivery).