Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

Behavioral health conditions (which include mental health and substance use disorders [MHSUDs]) affect approximately 20 percent of Americans (NIMH, 2017). Of those with a substance use disorder (SUD), approximately 60 percent also have a mental health disorder (CBHSQ, 2015). Together, these disorders account for a substantial burden of disability, have been associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality from other chronic illnesses, and can be risk factors for incarceration, homelessness, and death by suicide. In addition, they can compromise a person’s ability to seek out and afford health care and adhere to care recommendations (Roberts et al., 2015; WHO, 2015).

Despite the high rates of comorbidity of physical and behavioral health conditions, integrating services for these conditions into the American health care system has proved challenging. As many as 80 percent of patients with behavioral health conditions seek treatment in emergency rooms and primary care clinics, and between 60 and 70 percent of them are discharged without receiving behavioral health care services (Klein and Hostetter, 2014). More than two-thirds of primary care providers report that they are unable to con-

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

nect patients with behavioral health providers because of a shortage of mental health providers and health insurance barriers (Alliance for Health Policy, 2017; Cunningham, 2009). Part of the explanation for the lack of access to care lies in a historical legacy of discrimination and stigma that makes people reluctant to seek help and also led to segregated and inhumane services for those facing MHSUDs (Storholm et al., 2017). Moreover, health insurance programs often provide limited coverage of services for these disorders compared to services for other conditions, so there has been little or no financial incentive to bring behavioral health care into the primary care setting. However, even when services are covered, inadequate reimbursement or network adequacy may still limit access (Klein and Hostetter, 2014). While the majority of mental health services are currently delivered in primary care settings, the implementation of integrated care models shown to support delivery of evidence-based mental health services in primary care has been limited to demonstration programs with funding from time-limited grants (McGinty and Daumit, 2020).

In an effort to understanding the challenges and opportunities of providing essential components of care for people with MHSUDs in primary care settings, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Forum on Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders planned a 1-day, in-person workshop in Washington, DC. Given restrictions placed on travel and large public gatherings as a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the workshop (originally scheduled for June 3) was converted into a virtual workshop with three webinars held on June 3, July 29, and August 26, 2020, that addressed the following:

- Efforts to define essential components of care for people with MHSUDs in the primary care setting for three illustrative conditions (depression, alcohol use disorder, and opioid use disorder [OUD]);

- Opportunities to build the health care workforce and delivery models that incorporate those essential components of care; and

- Financial incentives and payment structures to support the implementation of those care models, including value-based payment strategies and practice-level incentives.

A paper commissioned by the Think Bigger Do Good Policy Series2 provided an overarching framework for the workshop (McGinty and Daumit, 2020). This paper was authored by the first webinar’s two speakers, Beth McGinty, associate professor, associate chair for research and practice, co-director of the Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research,

___________________

2 The Think Bigger Do Good Policy Series is a partnership of the Scattergood Foundation, Peg’s Foundation, Patrick P. Lee Foundation, and Peter & Elizabeth Tower Foundation.

and associate director of the ALACRITY Center for Health and Longevity in Mental Illness at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Gail Daumit, Samsung Professor of Medicine, vice chair for clinical and translational research, and director of the ALACRITY Center.

Howard Goldman, professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland at Baltimore School of Medicine and forum co-chair, opened the first virtual workshop, explaining that the paper was the product of a collaboration among the Think Bigger Do Good Policy Series, the National Academies, and the journal Psychiatric Services. “We have illustrated the kind of collaboration we can do within the behavioral health field, and it is now incumbent on us to do a better job in integrating behavioral health and general medical care,” said Goldman. Adding that this is not a new topic, Goldman shared that he wrote a background paper on the subject for the Institute of Medicine (IOM)3 about 40 years ago. At the time, the focus was on diagnosis and referral from general medicine to specialty care because, as he explained, “no one at that time thought that general medicine would really pay much attention to implementing evidence-based practices.”

Colleen Barry, the Fred and Julie Soper Professor and chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy, and forum co-chair, noted in her introductory remarks that this workshop was taking place while the nation was confronting two public health crises—the COVID-19 pandemic and the aftermath of the brutal murder of George Floyd—both with profound implications for mental health and well-being. “It is clear that persistent racism and income and health inequities are themselves public health crises with profound implications for mental health,” said Barry. “As we dive into a discussion of how to improve care for mental illness and addiction, we can all be motivated by the fact that the crises surrounding us today make the topics we are discussing all the more pressing and important.” Barry also remarked that researchers were documenting worsening mental health and substance use in the context of the pandemic, underscoring the importance of this workshop.

Overview of the Proceedings

As noted above, the virtual workshop unfolded over three webinars. The first webinar in the series explored the landscape of models of care, such

___________________

3 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM is used to refer to publications issued prior to July 2015.

as accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), and collaborative care arrangements, and how essential components of care for MHSUDs might be induced for those care models. The webinar also addressed policy issues related to implementing these models and the essential components of care.

The second webinar highlighted the essential components of care for three key conditions—depression, alcohol use disorder, and OUD—in primary care settings. The speakers also described key factors that support or impede implementation of these essential components.

The third webinar examined ways to improve the workforce to support providing the essential components of care. It also focused on addressing financing, payment, practice, and systems-level issues, policies, and incentives to support providing these components.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions of the 3 days of virtual sessions. A broad range of views was offered. Box 1 provides a summary of suggestions for potential actions from individual workshop participants. Appendixes A and B contain the workshop Statement of Task and the workshop agenda, respectively. The workshop speakers’ presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived online.4

MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH MHSUDs

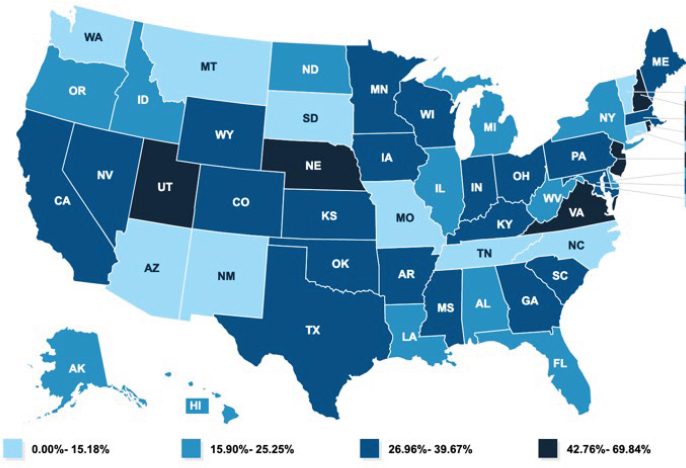

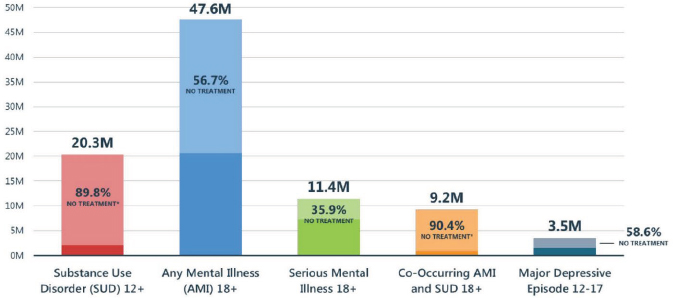

Daumit began her remarks by framing the problem confronting the care of people with MHSUDs. She noted that MHSUDs, also known as “behavioral health conditions,” are significantly undertreated in the United States. In fact, she said, although nearly 20 percent of U.S. adults experience a behavioral health issue every year, in 2018 only 43.3 percent of adults with mental illness received any mental health treatment, and only 11 percent with an SUD received addiction treatment (NAMI, 2019). Moreover, mental illness and SUDs are highly comorbid with one another—one in five U.S. adults with mental illness also experience an SUD (NIDA, 2010)—and with common physical health conditions, such as cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. HIV infection and chronic liver disease are common comorbidities with SUDs (SAMHSA, 2020).

Despite the high prevalence of comorbidity, physical illnesses are frequently undertreated in people with behavioral health conditions. This suboptimal care for people with behavioral health conditions has major health implications, Daumit explained. Depression is a leading cause of

___________________

4 For more information, see http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/MentalHealth/MentalHealthSubstanceUseDisorderForum/2019-OCT-15.aspx (accessed October 6, 2020).

disability, both in the United States and worldwide, and people with serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder, die at least 10 years prematurely relative to the overall population, mostly as a result of cardiovascular disease and other medical conditions (Bodenheimer et al., 2002). Notwithstanding the high burden of behavioral health conditions and their comorbidities, the U.S. mental health and addiction treatment systems have historically operated outside of the general medical system. This fragmentation, said Daumit, is an important driver of undertreatment.

Developing implementation models for integrating general medical care and behavioral health care—what is known as “integrated care”5—has been a priority in the clinical and health policy communities for decades, explained Daumit. Although the majority of mental health services are delivered in primary care settings (Coyne et al., 1994; Katon and Schulberg, 1992; Regier et al., 1993; Schulberg et al., 1995), Daumit stressed that integrated care models shown to be effective in clinical trials have not been widely implemented outside of demonstration programs or other time-limited mechanisms. “We have unrealized opportunities to address mental illness and SUDs in primary care settings,” she said.

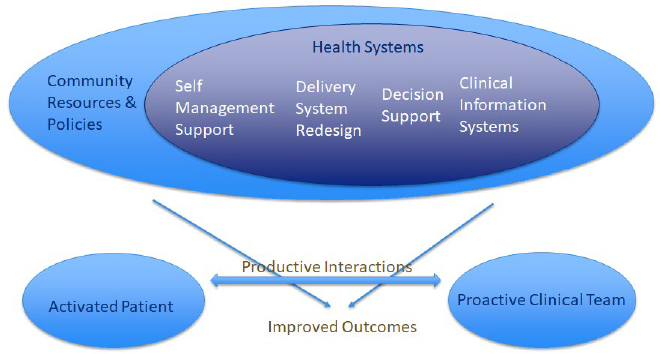

As Daumit pointed out, the majority of integrated care interventions shown in clinical trials to improve treatment delivery and patient outcomes implement variations of the collaborative care model,6 which is based on Wagner’s chronic care model (Wagner et al., 1996). That model (see Figure 1) defines essential elements of health systems, particularly team-based care, that encourage high-quality chronic disease care. It encompasses elements of community resources and policies from within the health system, self-management support, delivery system redesign, decision support, and clinical information systems. “These elements facilitate productive interactions between activated patients and a proactive clinical team to improve health outcomes,” explained Daumit.

Daumit explained that the collaborative care model was developed by researchers at Group Health and the University of Washington to focus on improving care in the primary care setting for individuals with depression. In collaborative care, primary care physicians work with a care manager and consulting psychiatrist to proactively identify, treat, and monitor people with behavioral health conditions.

___________________

5 According to the World Health Organization, integrated care is defined as “the organization and management of health services so that people get the care they need, when they need it, in ways that are user-friendly, achieve the desired results and provide value for money” (Waddington et al., 2008).

6 Collaborative care refers specifically to the blending of mental and physical health care in order to provide patient-centered, comprehensive, accountable care (Insel, 2015; Katon et al., 1995).

SOURCES: As presented by Gail Daumit, June 3, 2020; adapted from Wagner, E. H., B. T. Austin, and M. Von Korff. 1996. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly 74(4):511–544. Reprinted with permission from the Milbank Memorial Fund.

Daumit pointed out that the core tenets of the collaborative care model include population-based care, measurement-based care, and stepped care (see Table 1). She noted that population-based care differs from care in which clinicians see one patient after another individually and focus only on the patient in front of them rather than the broader population of people with a certain condition.

TABLE 1 Core Tenets of the Collaborative Care Model

| Core Tenets of the Collaborative Care Model | Description |

|---|---|

| Population-based care |

|

| Measurement-based care |

|

| Stepped care |

|

SOURCES: As presented by Gail Daumit, June 3, 2020; adapted from McGinty and Daumit, 2020.

In measurement-based care, the Patient Health Questionnaire major depressive disorder module (PHQ-9), for example, could serve to both diagnose depression and identify those individuals who are not improving with treatment. In terms of stepped care, failure to intensify treatment is common for patients with depression who are treated in primary care, explained Daumit (Pence et al., 2012; Unützer and Park, 2012).

As Daumit explained, there is a large and conclusive body of evidence from randomized controlled trials supporting the beneficial effects of collaborative care, in terms of both access to care and patient outcomes, for patients with depression in the primary care setting (Bao et al., 2015; Ginsburg et al., 2018; Simon, 2006). Evidence also suggests that collaborative care could benefit individuals with anxiety (Archer et al., 2012; Curth et al., 2019), bipolar disorder (Reilly et al., 2013), schizophrenia (Baker et al., 2019; Neville, 2015), SUDs (Jeffries et al., 2013; Wiktorowicz et al., 2019), and comorbid health conditions (Camacho et al., 2018; Coventry et al., 2015).

Daumit explained that the main issue with implementing the collaborative care model is that it is complex and requires team members from multiple specialties. She noted several simpler models of integrative care, such as the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) model (Agerwala and McCance-Katz, 2012; SAMHSA, 2013) and the consultation-liaison model (Gillies et al., 2015; Meadows et al., 2007; Muskin, 2017).

Daumit pointed out that the SBIRT model has been used predominantly for treating alcohol use disorder and other SUDs. The model applies a validated screening process to identify patients and stratify them by level of risk. Daumit noted that low-risk patients might receive brief behavioral therapy for an SUD and a motivational enhancement intervention designed to help them change their behavior, while high-risk patients would receive a referral for specialty treatment. SBIRT has been tested primarily in primary care and emergency department (ED) settings, and the resulting small body of research has produced mixed results. Daumit noted that one high-quality trial found no effects on alcohol or substance use after a 6-month follow-up (Drake et al., 2009). However, she added, a recent systematic review did find that brief interventions delivered in primary care or ED settings can reduce alcohol consumption and improve alcohol consumption behaviors (Driessen and Zhang, 2017).

Daumit defined consultation-liaison models as those where processes exist for the primary care provider to consult with a behavioral health specialist. She explained that some studies suggest this approach can improve depression outcomes and reduce the length of general medical inpatient hospitalizations among those with mental illness. She cautioned, however, that “we need more data on these kinds of integrated care models to know how they really work.”

Key Elements of Integrated Care

McGinty shifted the focus to the key elements of integrated care: process-of-care and structural elements (see Table 2). McGinty explained that the process-of-care elements include proactively and systematically identifying patients and connecting them to evidence-based treatments. Proactivity, she pointed out, is a hallmark of Wagner’s chronic care model and stands in contrast to traditional medical practice, which historically responds to a patient’s needs as they appear during an exam. She noted the importance of the structural elements that are needed to implement the process-of-care elements.

Policies to Support Integrated Care

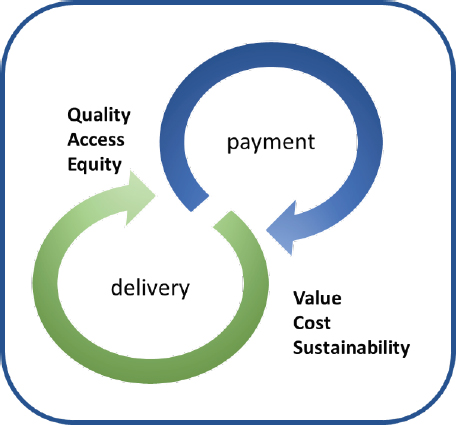

Pivoting to a discussion of policies to support integrated care, McGinty explained that most policy actions so far have focused on financing mechanisms. She emphasized that a major barrier to scaling integrated care is the lack of insurance reimbursement mechanisms for the key process-of-care and structural elements, such as care management. She pointed out the three main approaches to addressing this barrier: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) behavioral integration codes, primary care medical home reimbursement strategies, and ACOs.

TABLE 2 Key Elements of Integrated Care

| Key Elements of Integrated Care | |

|---|---|

| Process-of-Care Elements | Structural Elements |

|

|

SOURCES: As presented by Beth McGinty, June 3, 2020; adapted from McGinty and Daumit, 2020.

CMS behavioral health integration billing codes, introduced in 2017, are per-person, per-month billing codes adopted by Medicare, some commercial payers, and some state Medicaid plans (Carlo et al., 2018, 2020). General medical providers can use four of these codes, three of which are for care management and care coordination services delivered specifically within a collaborative care model and the fourth is for care management and behavioral health care management services delivered in any type of integrated care model. McGinty referred to a study that examined uptake of these billing codes, which found that only 0.1 percent of Medicare beneficiaries with MHSUDs had a behavioral health integration billing code indicating they received one of these integration services (Carlo et al., 2019; Cross et al., 2019). Of that 0.1 percent, 75 percent of the billing codes were for general behavioral health integration services rather than a collaborative care service. Subsequent qualitative work aimed at exploring the reasons why uptake of billing codes for integrated care is so low found that many practices lack the structural elements needed to provide the services to use the codes, particularly for the collaborative care codes that require a practice to have a consulting psychiatrist and a behavioral health care manager.

Turning to PCMHs, McGinty noted that they are focused on improving primary care more broadly rather than focusing explicitly on behavioral health integration. She did note, however, that PCMHs are also based on Wagner’s chronic care model, which has been used increasingly to integrate behavioral health into primary care. Some PCMH programs have used a relatively modest per-member, per-month payment of $20–$200 per beneficiary to cover care management or other previously nonbillable process-of-care services. McGinty emphasized that two federal demonstration projects—the Comprehensive Primary Care Program (Peikes et al., 2018) and the Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Demonstration Program (Leung et al., 2019)—failed to lead to high uptake of evidence-based behavioral integration practices.

McGinty noted that ACOs, the third approach to support integrated care, are like PCMHs in that they are not focused specifically on behavioral health integration. However, ACOs can incentivize behavioral health integration through shared savings, and potentially losses, in two-sided risk arrangements tied to achieving quality of care and health care spending targets. Despite the proliferation of ACOs in the United States, McGinty noted that the available evidence reveals that ACOs have had some small but not clinically meaningful effects on care for people with MHSUDs (Busch et al., 2016; Gordon, 2016; O’Donnell et al., 2013). One reason for this limited impact, she explained, is that behavioral health specialists are often excluded from ACO networks. In addition, ACO payment incentives have emphasized metrics for general medical conditions and not behavioral health.

McGinty explained three major lessons learned from these various attempts to use policy to incentivize integrating primary care and behavioral

health care. First, multi-payer financing arrangements are important for supporting both process-of-care and structural elements of integrated care models. Behavioral health integration billing codes have so far focused on process-of-care elements, but frontline providers report that they cannot implement those elements because they do not have the structural elements in place.

Second, McGinty noted, primary care has to be accountable for the health of the whole person. “We have historically held primary care physicians responsible for general medical conditions and behavioral health specialists responsible for behavioral health conditions, and that does not incentivize truly meaningful collaboration and care integration around improving the health of the whole person,” said McGinty. ACOs, because they have incentives to improve “whole-person” health, could be part of the answer if policies more effectively addressed some of the barriers discussed above, such as the failure to appropriately align payment incentives with behavioral health performance metrics.

Third, policy barriers that are antithetical to integrating care still exist, such as multiple state Medicaid programs prohibiting clinicians from billing for a general medical service and a behavioral health service for the same person on the same day, said McGinty. While the 21st Century Cures Act7 clarified that federal law does not prohibit same-day billing, several states still maintain that prohibition. McGinty noted that behavioral health carve-outs, where behavioral health benefits are administered by a separate organization than general medical benefits are, are a major policy issue in today’s behavioral health policy dialogue. Some providers and insurers have cited this separation of benefit management as a barrier to integrated care, though evidence supporting that is limited. One study examined the effects of carving in behavioral health benefits in the Illinois Medicaid program and found that doing so decreased the cost of behavioral health care without changing use (Xiang et al., 2019). McGinty warned that the study, however, failed to answer key questions about the degree to which that carve-in prompted care integration processes and improvements in quality of care or health outcomes for people with behavioral health conditions.

McGinty explained that various condition-specific policy barriers exist as well. For example, federal regulations require primary care providers to obtain a special waiver from the federal government to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD. Primary care providers are also prohibited from prescribing methadone.

Ultimately, in McGinty’s view, financing policies are likely to be necessary but not sufficient to truly prompt adoption of complex, effective integrated care models. She sees a strong need for additional policy activity regarding

___________________

7 For more information, see Public Law 114-255. See https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/34 (accessed August 25, 2020).

the behavioral health workforce. Primary care clinicians often cite a shortage of behavioral health workers as a barrier to implementing integrated care. Options to address this issue range from traditional health care workforce policies to adopting better reimbursement policies for telemedicine to deliver behavioral health services. McGinty shared her hope that the rapidly evolving telemedicine landscape prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic will provide some important lessons. She emphasized that meaningfully addressing the behavioral health workforce problem will require reimbursing behavioral health services at a sufficiently high rate to incentivize clinicians to choose challenging behavioral health careers.

As a final comment, McGinty noted that the adverse social determinants of health—including poverty, unemployment, housing instability, and involvement with the criminal justice system—are overrepresented among people with behavioral health problems. These factors also contribute to many of the barriers to care and poor health outcomes that individuals with MHSUDs experience. McGinty pointed to the range of policy options available to address the social determinants, particularly large-scale social safety net policies that target groups that include but are not limited to those with behavioral health issues. “I would also highlight the need to think about models that integrate not only general medical and behavioral health care but also social services,” said McGinty. Accountable health communities,8 which extend the ACO model into the community, may offer some lessons about the types of policies that can incentivize that type of three-way integration.

Panel Reactions and Discussion

Ruth Shim, the Luke & Grace Kim Professor in Cultural Psychiatry and associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, Davis, said that she was struck by McGinty’s final comments about the social determinants of health and the importance of figuring out how to integrate these and the social determinants of mental health into the work on integrating behavioral health care into primary care. “I feel that we are gaining traction in that space,” said Shim. “I think that in

___________________

8 According to CMS, the Accountable Health Communities Model is based on emerging evidence that addressing health-related social needs through enhanced clinical–community linkages can improve health outcomes and reduce costs. Unmet health-related social needs, such as food insecurity and inadequate or unstable housing, may increase the risk of developing chronic conditions, reduce an individual’s ability to manage these conditions, increase health care costs, and lead to avoidable health care use. For more information, see https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm (accessed October 26, 2020).

the past several years, there has been movement to incorporate more work around social determinants of health and bringing all of that into the world of integrated behavioral health care.”

Barry agreed with Shim and added that historical legacies are still slowing progress on integrating primary care and behavioral health care. “It is discouraging, frankly, and we need to figure out how to move the ball,” said Barry, “but we need, as Beth and Gail have nicely done, to diagnose the problems first.”

For Barry, the reason behavioral health issues are treated differently than general medical issues comes down to economics, institutional policies, or stigma. Barry noted her concern that the financial strains health care systems are experiencing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic will lead to strong incentives to cut costs. She fears that such pressures will limit integration efforts, given the inherent slowness of health care institutions to evolve. Barry added that she sees little progress in lowering the stigma associated with behavioral health issues.

Deidra Roach, medical project officer in the Division of Treatment and Recovery Research at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), agreed that advancing integration efforts will depend on economics, institutional policy, and stigma and also require community participation. “I think [community participation] is a factor that has been largely overlooked in our planning of integrated care and that could make a significant difference in what our progress will be going forward,” said Roach. Noting the important role research will play, Roach strongly recommended that researchers use a community-based participatory model to take advantage of the wisdom of those living in the community, which may help resolve some of the existing structural issues.

Goldman asked the speakers to describe their key qualitative ingredients of integrated care, including the difficult-to-measure constructs, such as communication or teamwork. Daumit said that she believes these qualitative aspects of integrated care are both important and difficult to measure and pointed to the key qualitative ingredients of integrated care listed in the McGinty and Daumit paper:

- The belief of primary care clinicians and other people in a practice about the importance of population health, the goal of improving whole-person health, and shared values around these ideas;

- The implementation climate;

- How supportive leadership is of integrated care and evidence-based practice around collaborative care; and

- Whether clinicians have the self-efficacy to deliver integrated care (McGinty and Daumit, 2020).

Shim asked the speakers to comment on the cultural shifts needed to facilitate care integration and how to achieve them. Daumit said that organizational culture is incredibly important, and she posed questions to ask about that culture. “What is leadership thinking? What are all the different levels of clinicians and staff thinking, and what are the explicit and implicit incentives, formal and informal, that are contributing to that culture and climate?” In her opinion, the shift from differentiating physical health and mental health toward shared responsibility to the whole person will require medical training to end the practice of placing each discipline in separate silos. In addition, leadership will need to emphasize to all levels of the organization that new evidence-based practices are important to learn and implement. Finally, she said, financial incentives should support the cultural shifts toward integration.

Regarding the major barriers that the workforce itself poses to integration, McGinty said that she thinks of workforce issues as falling into one of two categories: the shortage of behavioral health workers and gaps in competencies among the current workforce. She noted that she addressed certain strategies for overcoming workforce shortages in her presentation, particularly the need to pay adequately for behavioral health services in order to create competitive financial packages for these clinicians at all levels, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

McGinty added that a silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is the expanded use of telehealth. While telehealth will not increase the number of behavioral health providers, it does allow them to extend their geographic reach into underserved regions of the country. Maximizing telehealth, though, will require policies designed to address the digital divide. To address the clinician training issue, McGinty said that it is important to ensure that accreditation policies require general medical providers to receive some training in delivering mental health care, and vice versa, and also that all clinicians receive training in team-based care.

Roach commented that one of the most troubling observations is that when key elements of collaborative care are implemented in real-world settings, the benefits for individuals with depression have been minimal (Solberg et al., 2013). McGinty said that understanding why that is true is the million-dollar question. After all, multiple rigorous clinical trials have found that collaborative care-based models can be effective at improving depression symptoms and improving outcomes for people with SUDs. Nevertheless, evaluation of the Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction Initiative9—a statewide effort to implement depression care in primary care settings (Solberg et al., 2013)—showed that while it expanded the

___________________

9 For more information, see https://aims.uw.edu/depression-improvement-across-minnesota-offering-new-direction-diamond (accessed August 25, 2020).

delivery of depression care in the primary care setting, there were no effects on patient outcomes in terms of improving depression symptoms or remission (ICSI, 2014). McGinty noted that this was the case even though the initiative included a care management tracking system and payment designs to cover both process-of-care and structural elements along with intensive training for leaders, frontline providers, and staff.

This discouraging result has researchers trying to determine which key elements of the collaborative care model are not being translated from clinical trials to real-world contexts. Daumit mentioned one possibility, which has yet to be tested empirically: treatment intensification was not occurring in the real-world setting to the degree that it took place in the experimental setting. Daumit added that she hopes efforts to improve primary care, which has its own issues, will incorporate behavioral health priorities.

Goldman, posing a final question before inviting questions from webinar participants, asked McGinty about any downsides to the carve-in arrangements she mentioned in her presentation. There could be, she acknowledged, particularly because no strong evidence shows that such arrangements are good for behavioral integration. “It makes intuitive sense on many levels, but it has not, at this point, been empirically demonstrated,” she said. One place where carve-outs work well, she noted, is for specific specialty services, such as psychiatric rehabilitation or intensive outpatient care that may not have clear parallels on the general medical services side. Daumit agreed that a well-run carve-in could benefit behavioral health care integration, but she worries that when budgets and services are cut, behavioral health services will be the first to go.

Question and Answer Session with the Webinar Participants

A webinar participant asked the panelists to comment on the role of training primary care providers regarding stigmatization of people with MHSUDs. This participant noted that they had heard primary care providers say that they do not want their practices to be places where “those people” come for care. Daumit replied that there may be a need to better screen those who are admitted to medical school in addition to providing better training. “I think that once people go into their practices and health care organizations, the organizational culture cannot tolerate anything like this anymore,” said Daumit. “I think we need to recognize consumers with mental illness and substance use problems as a population [for which there are significant] disparities that deserves all the same interventions to break down stigma as other minority and disabled populations have had over the years.”

McGinty noted that anti-bias training for clinicians can be effective in reducing race-related biases, and the same type of training is needed for stigma

surrounding MHSUDs. McGinty referred to a national study of primary care physicians and their attitudes about people with OUD (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2020; McGinty et al., 2020) that she and her colleagues completed recently. The study revealed that primary care physicians endorse the medical model of OUD and do not believe that SUDs in general are a moral failing and the individual’s fault. At the same time, they hold other quite stigmatizing attitudes toward people with OUD. “They are very unwilling to have a person with opioid use disorder, even a person who is on stable treatment with guideline-concordant medication, as a neighbor or marry[ing] into their family,” said McGinty. “They do not want a clinic that provides buprenorphine or methadone in the neighborhood where they live.” Addressing these attitudes requires anti-bias training, she added.

In Shim’s view, the issue goes beyond stigma and is a case of systemic structural discrimination against people with serious mental illness and SUDs. “I appreciate Gail’s comment that we have to do a better job of evaluating the workforce and making sure that the people that we bring into the profession do not harbor discriminatory beliefs toward people with serious mental illness and SUDs,” said Shim. Roach added that anti-bias training needs to begin at the earliest stage in the education of providers, even well before medical school, because these attitudes become ingrained at an early age and are difficult to reverse after that. McGinty remarked that it is important to recognize that anti-bias training and anti-stigma training alone are likely not enough. Rather, she said, they need to be paired with policy and system-level changes that empower clinicians to work with people with behavioral health disorders in a way that is effective for all people.

There were multiple questions from the webinar participants regarding CMS behavioral billing codes. One question was whether Medicaid Section 1115 waivers10 could be used to promote adoption by and provide technical assistance to primary care practices. McGinty responded that she was not aware of any states doing that, but this does seem to be a potential use. “I do think there is definitely a role for technical assistance around use of these codes and support in helping to get some of the structures in place to help practices bill these codes,” she said, adding that technical assistance alone will not address

___________________

10 Section 1115 of the Social Security Act gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services authority to approve experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that the secretary finds to be likely to assist in promoting the objectives of the Medicaid program. Section 1115 demonstration projects present an opportunity for states to institute reforms that go beyond routine medical care and focus on evidence-based interventions that drive better health outcomes and quality of life improvements. For more information, see https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/about-section-1115-demonstrations/index.html (accessed June 23, 2020).

staffing elements of care. Goldman noted that the Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center at the University of Washington has provided technical assistance on both the conduct of collaborative of care and some of the policy issues discussed during the webinar. It also has a collaborative care implementation guide available for downloading.11

The final question focused on whether there is evidence that any of the many approaches to integrating behavioral and physical health are more effective. Daumit responded that multiple clinical trials offer evidence that the collaborative care model of integrating behavioral health into primary care is effective for depression and anxiety. Much less evidence exists, she said, regarding efforts to bring physical health care services into behavioral health care settings.

Closing Remarks of the First Webinar

In closing, Roach observed that although the participants could not be together physically, she still felt the energy of a committed community. “We believe that energy is transforming health care in the U.S.,” said Roach, “such that in the foreseeable future it will consistently reflect the reality that optimal physical health is only possible when there is optimal mental health and vice versa.”

ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF CARE FOR THREE MHSUD CONDITIONS IN PRIMARY CARE SETTINGS

Goldman introduced the second webinar by explaining that the day’s panelists would elaborate on their understanding of the essential components of care for three illustrative conditions: depression, alcohol use disorder, and OUD. The panelists were also charged with highlighting crosscutting components of care and possible differences among those conditions. Goldman encouraged the panelists to explore the issues important to prevention, screening, case identification, and treatment in primary care settings, including those with limited resources.

Exploring the Essential Components of Care for Alcohol Use Disorder in Primary Care Settings

Richard Saitz, professor and chair of the Department of Community Health Sciences at the Boston University School of Medicine and School of Public Health, began his remarks with an anecdote reflecting the challenge of

___________________

11 For more information, https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/implementation-guide (accessed November 23, 2020).

caring for individuals with alcohol use disorder in primary care. He explained that in 2015, he and a colleague came across a paper in a major medical journal that validated a screening tool for alcohol and other drug use disorders (Tiet et al., 2015). His colleague wrote a letter to the journal pointing out that this tool, while useful for identifying these disorders, would not identify the full spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use. When the letter was published (McNeely and Saitz, 2015), the editor added a note that acknowledged that the field of drug use and screening would benefit from clarity in terminology—distinguishing between substance use and an SUD—and added, “However, in practice, it can be very challenging to distinguish between substance use and an SUD.”

Saitz was stunned by the response. “I was really shocked that an editor of a major medical journal would admit and write down that it would be hard to tell the difference between substance use and SUD,” he said. “It is almost like saying that you could not tell the difference between high cholesterol and myocardial infarction or an elevated glucose [level] and a diagnosis of diabetes.” In fact, Saitz pointed out, alcohol use disorder and the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use taken together are similar to the spectrum of elevated cholesterol or glucose levels and their respective progression to heart disease and diabetes. He described that the spectrum of alcohol use begins at abstinence; proceeds to low-risk use, risky use, at-risk use, and hazardous use; and culminates in alcohol use disorder. As consumption increases, so do the associated consequences, Saitz added.

Saitz described what he considered the essential components of care: identify the disorder, discuss the diagnosis and treatments with the patient, treat the disorder, and refer the individual for services and specialized care. “These are similar components of care across many conditions, medical, psychiatric, and otherwise,” he said. Saitz pointed out that for alcohol use disorder, one single question—how many times in the past year have you had five or more drinks in 1 day for a man or four for a woman—is a simple, validated screening test (Smith et al., 2009).

Saitz explained that the next step is to identify any consequences of excessive use to determine if the individual has an alcohol use disorder. The 11 criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (APA, 2013) serve that function. In terms of discussing this diagnosis and possible treatments with the individual, Saitz said that there is no difference between how the primary care physician should address alcohol use disorder or a condition such as hypertension. Saitz noted that while some individuals may deny they have an alcohol use disorder and not want to treat it, this is similar to how some people with hypertension deny they have a problem because they are not feeling any symptoms.

In Saitz’s view, the SBIRT model has shortcomings because it only includes a brief intervention and then referral and does not include treating

alcohol use disorder as an essential component of care. “Although I am an addiction specialist as well as a primary care physician, I will say that treatment for alcohol use disorder is not really that complicated,” noted Saitz. There are four available medications, he explained, and primary care providers can monitor response simply by asking about drinking, any side effects, and the patient’s challenges and successes. If an individual requires more comprehensive care than the clinician can offer with repeated counseling and medication, the clinician will refer the patient for specialized treatment in the same way as for a patient who was not responding to high blood pressure treatments.

The task ahead, said Saitz, is to convince the primary care clinical community that addressing alcohol use disorder is not very different from identifying and treating hypertension or diabetes. Saitz added that while there are comorbidities associated with alcohol use disorder, primary care providers are accustomed to addressing multimorbidities. While acknowledging that primary care providers are already stretched for time, Saitz noted that he has never heard a primary care physician say they do not have enough time to treat hypertension or diabetes. In fact, he added, it is more difficult to get someone to take insulin for diabetes than it is to prescribe daily naltrexone for alcohol use disorder. In closing, Saitz suggested convincing primary care providers that alcohol use disorder is their responsibility so that they take on that role and address the stigma and systems that act as barriers to care.

The Case for Integrating MHSUDs into Primary Care

Sarah Wakeman, medical director for the Substance Use Disorders Initiative, program director of the Addiction Medicine Fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital, and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard University, began her remarks by pointing out that when making a case to primary care providers about treating SUDs, it is critical to understand what the patient wants. Wakeman noted that it is irrelevant, for example, if she believes that a person should make changes related to their drug or alcohol use. Rather, it only matters if the patient believes their life is going to be better if they do so. She added that it does not matter that she thinks all primary care doctors should be treating alcohol and drug use disorders. “The point is, why might primary care doctors think that this is in their purview and as important as treating diabetes or hypertension?” she asked.

The answer, she said, ties into the three devastating public health crises affecting the nation: the drug overdose crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the epidemic of racism. She noted that addiction medicine is a field closely tied to racism, given that the nation’s drug policy has its roots in racism. She explained that people of color experience discrimination under every com-

ponent of U.S. drug policy and at every stage of the criminal justice system. “If we are going to talk about racism, we have to talk about drug policy, and part of that is about identifying and treating those who do have [an] SUD as having a medical condition,” explained Wakeman.

She then explained that the second reason primary care should include alcohol and substance use treatment in its purview is that treatment in primary care is feasible, effective, and rewarding. It is much more difficult, for example, to safely manage anticoagulation or insulin titration, heart failure, and many other issues that primary care is adept at treating. In Wakeman’s experience, primary care providers say they do not have the time or skillset to treat alcohol and drug use disorders for two reasons. First, treatment is not taught in medical school. Second, because of this, primary care has been given a pass on thinking of these disorders as medical conditions that should be addressed as part of what is normally considered general medical care.

As Wakeman observed, multiple studies have shown that these disorders can be effectively treated in primary care with outcomes that are as good as in specialty care settings. She cited one study that examined buprenorphine treatment in primary care, with or without adjunctive psychosocial addiction treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (Fiellin et al., 2014), and found no difference in study completion, opioid use, or cocaine use between primary care medication management with or without adjunctive psychosocial intervention. The fact is, said Wakeman, primary care providers can manage these conditions, and that is often where patients want to receive treatment—by the doctors and care teams they trust.

Wakeman pointed out that one important task for primary care “is to reframe the way we think about care for people who use substances and the ways that we inadvertently harm people in our health care system who use alcohol and drugs.” As an example, she explained that if a person came into the hospital experiencing a myocardial infarction and recurrent chest pain, they would not be discharged against medical advice. “And yet if a person with an SUD is in the hospital and is having ongoing substance use, often the response is this punitive one of kicking people out of care or forcing them out of care,” said Wakeman.

She observed that while the medical profession talks about the harm that alcohol and drug use does to people’s health, many of the health consequences of substance use are related to health system policies and approaches. Drug users, for example, do not get infective endocarditis from heroin but rather as a result of contaminated drug supplies and a punitive drug policy approach that forces people to use heroin in secrecy and in unsanitary conditions—without access to safer injection equipment or supervised injection sites. In addition, the health care system often treats people who use drugs and alcohol differ-

ently than other patients in terms of security, visitor policies, and the length of time they are allowed to stay in the hospital. Wakeman noted that “in those ways, the health outcomes and health harms of someone’s substance use are more related to our approaches, to discrimination and stigma, than to the actual substance itself.”

For Wakeman, developing a system of care that treats SUDs and delivers effective medical care to all patients who use substances requires thinking about what patient-centered and patient-guided care really mean. As with any other disorder, the patient’s needs, wants, and preferences should be what the primary care system focuses on first, not what providers think is the most important need. Wakeman explained that she and her primary care colleagues take the approach that caring for those with an SUD is both the right thing to do and the smart thing to do if the goal is to take better care of populations, keep people out of the hospital, reduce health care costs, and keep patients healthy.

Wakeman observed that one reason providers tend to blame patients for their substance use issues is that these providers can feel helpless and do not know what to do. The remedy to this problem is to provide clinicians with tools they need to be able to successfully treat these patients. Wakeman noted that one approach is to use addiction champions—doctors, nurses, behavioral health providers, and recovery coaches—who themselves have had experience with an SUD. Addiction champions are valuable members of multidisciplinary teams and can deliver a multidisciplinary care model, much like what is used to care for patients with HIV or diabetes.

Wakeman stressed that it will be important to study different care models to determine what aspects are effective and which are not and to inform the primary care community about the results of those studies. She and her colleagues, for example, looked at practices with or without integrated SUD care and found that individuals with SUDs who received care in a practice without integrated services had more ED visits and a higher number of total inpatient bed days (Wakeman et al., 2019).

Wakeman added that while data are important, narrative and patient stories can be valuable in terms of spreading hope and giving people—patients and their health care teams—a tangible reminder that an SUD is a highly treatable condition with a good prognosis. “I do not think the first thing many of our providers think, when they hear about someone who is injecting heroin or fentanyl, is ‘wow, that is incredibly treatable,’” said Wakeman, “and yet it is.” Many people, she said, will achieve remission and go on to live healthy lives, and helping an individual get to that place is incredibly rewarding to providers. She added that embedding recovery coaches in the system has been one powerful way to consistently remind people of that message of hope.

In closing, Wakeman shared a quotation from one of her institution’s 14 recovery coaches:

I am a woman in long-term recovery from opioid use disorder. Facing early trauma and adversity at a young age, I struggled with a severe opioid use disorder for 17 years and had almost given up hope. I began to have multiple critical infections as a result of my use and luckily was finally introduced to a medication to treat my opioid use disorder. Without the treatment of buprenorphine, I would never have been able to build the foundation of my recovery supports [that] I now stand on 6+ years later. I am incredibly proud to say I have a leadership role at a major medical center working to help patients such as myself with substance use disorder. I am also a mom to the most amazing little boy, a wife to an amazing husband, and a homeowner. Without that initial treatment of buprenorphine, I know none of these things would have been possible.

Implementing Collaborative Care Treatment for Depression

Lydia Chwastiak, professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and co-director of the Northwest Mental Health Technology Transfer Center at the University of Washington, opened her remarks by noting that the majority of integrated care interventions that have been shown in clinical trials to improve depression outcomes have been some variation of collaborative care. In fact, she said, evidence from more than 80 randomized controlled trials supports the effectiveness of collaborative care for improving depression and anxiety outcomes (Archer et al., 2012). The first large, multi-site trial to demonstrate its effectiveness in treating depression was the Improving Mood–Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) trial, which involved 2,000 participants at 8 health care organizations (Unützer et al., 2002).

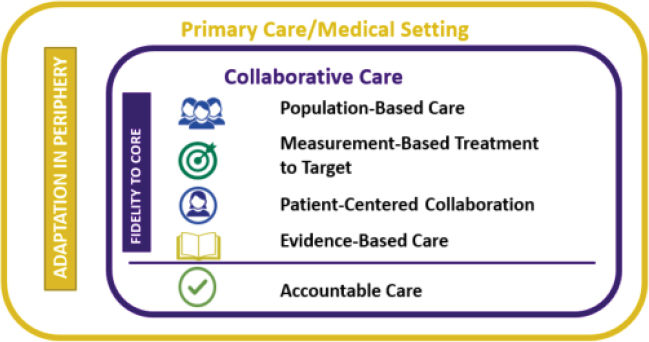

Chwastiak explained that collaborative care is derived from the chronic care model, and it has five core principles that provide the foundation for effective implementation (see Figure 2).

Chwastiak noted that the primary care provider is a critical member of the collaborative care team and continues to prescribe and monitor all medications. In addition, collaborative care adds two members to the primary care team that treats depression. The first is a behavioral health care manager, often a social worker, who is integrated into the primary care team. The care manager has two sets of tasks: general care management, such as tracking and coordinating care and conducting systematic follow-up, and providing evidence-based brief behavioral interventions for depression or anxiety. The second new team member is a psychiatric consultant who is typically not in the primary care clinic and does not see patients directly but does spend 2–3

SOURCES: As presented by Lydia Chwastiak, July 29, 2020; used with permission from the University of Washington AIMS Center, 2020.

hours per week working with the care team, including taking part in a structured weekly caseload review meeting with the care manager.

Chwastiak noted that studies have shown that collaborative care is not only significantly more effective than usual care but also associated with a shorter time to depression remission (Garrison et al., 2016). For example, data from a large, statewide collaborative care implementation project in Minnesota, conducted over 5 years with more than 7,300 individuals with depression, showed that the mean time to remission of symptoms was 86 days for those who received collaborative care. In contrast, it was 614 days, or seven times longer, for those who received usual primary care (Garrison et al., 2016). She noted that a typical course of treatment in collaborative care is 6–12 months, and between 50 and 75 percent of the individuals in treatment will require at least one change of treatment during that time. Collaborative care’s use of measurement-based care and “treatment-to-target” facilitate timely treatment adjustments that are critical to reducing time to response. Chwastiak noted that treatment-to-target in this context involves defining a measurable target for treatment—such as a PHQ-9 score of less than 5 for depression remission—and then monitoring the desired outcome at clinical visits with regular review to iteratively adjust treatment.

Chwastiak explained that measurement-based care and treatment-to-target are only as effective as the actual depression treatment provided, which is why the use of evidence-based treatments is the fourth core element of collaborative care. Collaborative care uses both guideline-adherent medications for depression and brief psychotherapy interventions that fit a treatment schedule

of 30-minute visits every other week. She noted that structured, manualized treatments, such as problem-solving therapy and behavioral activation, are most feasible for this context.

Chwastiak pointed out that the final element of collaborative care, accountable care, means that collaborative care increases access to care and, in doing so, provides care to more patients and minimizes the time between identification and care. Collaborative care is accountable care because it (1) includes a systematic approach to identifying individuals who would benefit from care, and (2) incorporates a strategy of continuous quality improvement in terms of both treatment of individual patients and evaluation of program performance. Chwastiak stressed that collaborative care, like any evidence-based intervention, needs to be adapted to the specific setting in which it is implemented, but while every implementing organization makes some changes to the model, the core principles must be retained for effective implementation.

In her organization’s experience, said Chwastiak, adequate staffing with trained employees who have dedicated time for their roles in collaborative care is essential for effective implementation of the model, as is effectively using a registry. Financing mechanisms also have played a critical role in sustaining the program in organizations around the country. Chwastiak explained that process-of-care elements that facilitate implementation of collaborative care include standardized screening and referral workflows, training teams and providing them with ongoing support, and operationalized accountability through audits and feedback.

Chwastiak pointed out some barriers to implementing the care model that her team has experienced: difficulties hiring a care manager or identifying a psychiatric consultant because of workforce shortages. She noted that telepsychiatry has proven to be an effective tool for extending the reach of psychiatric expertise and engaging a consulting psychiatrist for a collaborative care program. Currently, for example, through the Mental Health Integration Program, psychiatrists based at the University of Washington act as consulting psychiatrists for collaborative care programs in more than 100 community health centers across Washington State. There is also evidence that the role of the care manager on the collaborative care team can be conducted virtually and be effective. Chwastiak observed that telepsychiatry is increasingly important as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact the nation.

Recent research, said Chwastiak, has focused on developing and adapting models to comanage multiple conditions, such as depression and diabetes (Ali et al., 2020; Chwastiak et al., 2017). She added that these models need to also address social determinants of health systematically.

In closing, Chwastiak remarked that the 2017 CMS billing codes for collaborative care have represented a major advance for implementing this model. She pointed out that in her experience, uptake of these codes was

slow initially but has increased as Medicaid programs and some private payers adopted the codes.

Sustaining Successful Interventions in Primary Care Practices

Frank deGruy, the Woodward Chisholm Chair and professor of family medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, often thinks about successful primary care–based interventions for mental health problems and the reasons those interventions cannot sustain themselves after a successful demonstration. In deGruy’s experience, clinicians adopt a successful intervention and then tend to gradually drift back to pre-intervention workflows within 6 months to 1 year in the face of all the other responsibilities primary care providers have to fulfill. In fact, embedded behavioral care clinicians and embedded care managers are, in practice, primary care clinicians. “They get pulled into all of the other noisy, dirty problems that are more important at that moment and have great difficulty staying focused on the original problem for which they might have been hired into the practice,” said deGruy. To illustrate that point, he noted that of the 2,900 practices that implemented the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus model (CPC+) starting in 2017, more than 95 percent achieved some behavioral health integration by 2019, but only 700 of those practices looked anything like the collaborative care model despite it being the only model offered during the program’s first 3 years.12

DeGruy explained that the dominant integrated care model implemented over the past 15 years, integrated behavioral health in primary care (IBH-PC), embeds a care manager and a behavioral health clinician—usually a psychologist or social worker with or without a psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse practitioner—in the primary care clinic. He added that evaluating whether this type of integrated care is effective for addressing depression, anxiety disorders, SUDs, and alcohol use disorder is difficult because the IBH-PC model is not disease specific. “You are looking at integrated care as the active ingredient, applied differently in different practices to different conditions, according to that site’s most pressing problems or according to the patient’s most pressing problems,” explained deGruy.

In terms of the evidence base for integrated primary and behavioral health care, deGruy pointed to the results of Advancing Care Together, a Colorado-

___________________

12 CPC+ is a national advanced PCMH model that aims to strengthen primary care through regionally based multi-payer payment reform and care delivery transformation. CPC+ includes two primary care practice tracks with incrementally advanced care delivery requirements and payment options to meet the diverse needs of primary care practices in the United States. For more information, see https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/comprehensive-primary-care-plus (accessed August 12, 2020).

wide trial of an integrated primary care and behavioral health model (Green and Cifuentes, 2015). He noted that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Integration Academy13 maintains a research collection that focuses on evidence that supports various models for various conditions in various clinics. The Integration Academy also provides playbooks, guides for professional practice, assessment measures, and resources for treating OUD and other SUDs.

Based on his observations of integration efforts, both successful and less so, deGruy offered four suggestions about ways to study and assess whether an integration model is successful. First, it is critical to fully understand the work of primary care clinicians and reconceptualize interventions according to a revised understanding of the workflow in a primary care setting. “If we wish to develop sustainable interventions that fit into their workflow, I think dealing with disease-specific interventions is not likely to ever get us there,” said deGruy. DeGruy also suggested no longer running controlled clinical trials on these interventions. In his view, such trials are best deployed when an intervention can be standardized for a well-defined target population in which the context (comorbid conditions and family, social, and environmental factors that affect that population) is in effect irrelevant. “That does not describe usual primary care,” he said.

Third, deGruy asserted that disease-specific outcome measures are at best insufficient and at worst inappropriate and “crushingly burdensome.” In deGruy’s view, primary care’s demonstrated value to individuals and populations lies not in its ability to produce improvements in disease-specific outcomes but in overall health and longevity.

His final recommendation was to fully commit to garnering the needed resources to “actually develop and stabilize a sustainable model in primary care.” Primary care practices are stretched to the limit already and do not have the margin to plan and implement a workflow change, fit that into their other workflows, and then realize sufficient revenue from that added set of tasks to keep it as a first priority, said deGruy. “We have to quit trying to get quality on the cheap,” explained deGruy. In his opinion, the previous speakers had each described enormously successful interventions that will work in primary care but only if sufficient resources are allocated to keep those interventions as priorities in practice in the face of all the other demands being made of primary care. “As long as we expect primary care to contend with the tsunami of demands and expectations that keep pouring over the transom of what else needs to be done there, these are not going to be sustainable interventions,” he warned in closing.

___________________

13 For more information, see https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov (accessed August 12, 2020).

Panel Reactions and Discussion

Goldman opened the panel discussion by pointing out that he did not understand how IBH-PC or other integration models will overcome the difficulties deGruy identified in terms of implementation fidelity and financial sustainability, to which deGruy replied that there are several possible mechanisms by which a primary care practice can be financially sustainable with additional care managers and behavioral health clinicians. One approach is to increase billing through the increased productivity that occurs when there is a behavioral health clinician available to deal with complex behavioral issues. In fact, he said, he has observed team-based care that is efficient enough to cover the cost of the team members who may not be able to bill for their services. He noted, too, that when primary care practices are left to their own devices, they settle into what he called the “first generation of integrated hybrid models,” in which the embedded behavioral health clinicians take on whatever conditions with which patients present.

Responding to Goldman and deGruy’s comments, Chwastiak said that a criticism of the collaborative care model is that it is too complex for many organizations to implement. Yet, all integrated care models face some similar implementation challenges, such as workforce shortages of behavioral health care providers—which is particularly problematic for rural and frontier communities. Chwastiak noted that CMS billing codes for collaborative care have increased programs’ financial sustainability and led to increasing adoption of the model nationally. In Chwastiak’s view, the administrative requirements for using the CMS billing codes are modest but can be burdensome for small practices. She was careful to point out, however, that for all practices, there is a large clinical and administrative burden when services are only reimbursed by one payer, such as Medicare. Clinic staff then have to sort out what services can be billed to Medicaid and private insurance.

Commenting on the idea of stretching a model versus drifting from model fidelity, Chwastiak explained that many providers and clinics have been very creative in trying to flex the collaborative care model to fit the particular setting and patient population, but it is critical that programs maintain the four core components. Goldman noted that when he and his colleagues analyzed implementation results from the original IMPACT study,14 he was impressed with the robustness of the comprehensive care model in a wide array of primary care settings, including the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Kaiser Permanente, and private and multigroup practices.

Goldman then asked Chwastiak to talk about the type of adaptations that have to be made to address deGruy’s suggestion to move away from a

___________________

14 For more information, see https://aims.uw.edu/keyword-tagging/impact-trial (accessed August 25, 2020).

disease-specific model. She replied that it depends on the context in which the implementation will occur, the disorders that will be treated, and the composition of the care team. As an example, she explained that when she and her colleagues moved from treating depression to co-managing depression and diabetes, they found a completely different workflow in diabetes specialty clinics that required adaptations to the intervention. The key, she said, was to learn from the work on implementation science that has been done over the past decade or more to understand how to flexibly adapt the program while maintaining the core elements of the evidence-based intervention. In turn, deGruy seconded Chwastiak’s comment about implementation science and said that he believes that will be the way forward as far as adapting comprehensive care to work in regular primary care settings.

Pivoting to a new topic, Goldman asked Wakeman what her institution is doing about policies that reflect racism and structural racism associated with SUDs and alcohol use disorder. Wakeman replied that there are two parts to that question: how to change the outright discrimination and stigma people who have an SUD experience when they come into the health care system and how to address structural racism. Though these two are interwoven, she said, they have slightly different answers. Wakeman pointed out that in the ED, the key has been to identify peer champions—other ED personnel—who can lead efforts to catalyze change and address discrimination and stigma against people with SUDs.

Wakeman described how one idea for catalyzing change came from a resident who had studied behavioral economics. This resident developed a social media campaign called “Get Waivered” in which the ED chair invited staff to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine and were paid for their time doing so. In addition, those who took advantage of this offer were celebrated on social media and in faculty newsletters, and they earned an opioid recovery champion badge to wear with their hospital identification. “It was a way of making this work valued and recognizing people for what they were doing,” said Wakeman.

Another approach adopted by Wakeman’s institution was to start every faculty meeting with outcome stories for people the ED staff had seen weeks or months earlier. This enabled ED staff to better understand the positive impact their actions were having on the lives of people they treated, something that they rarely hear. “Now, 95 percent of our emergency medicine attendings are waivered to prescribe buprenorphine, and we now have 24/7 access in the emergency department,” said Wakeman.

She cautioned that addressing the bigger question of structural racism is much more difficult given how embedded it is throughout society and the health care system. One piece of the solution is to use data to identify where racism exists in all components of the care system, including addiction referrals, retention, and engagement. Wakeman added that for too long, people

have talked about race as a risk factor, when the real risk factor is racism and living in a racist society. Another aspect of the solution is to hire, retain, and promote Black and Latinx leaders in addiction medicine, starting early in the educational pipeline, to create an environment that is welcoming to Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color.

Wakeman shared that in her experience, people will leave the hospital prematurely because they feel they are being treated poorly or have competing priorities that the health care system has not recognized. She and her colleagues have found that people being treated for an SUD come to believe they are being treated differently than others in the hospital or that being hospitalized feels like being incarcerated, something many patients with an SUD have experienced. Often, she said, health care providers believe they are doing something good and protecting patients from trying to access drugs while they are in the hospital, rather than seeing that those actions are actually hurting their patients.

Goldman then asked Saitz to talk more about the decision to treat someone in the primary care setting or refer them to a specialty clinic. Saitz replied that this is not an either/or situation. “Of course we need to do some disease-specific things because there are specific treatments that improve disease-specific outcomes, and, in doing so, they often translate into overall better health as perceived by the patient,” he said. Some of the specific treatments for alcohol use disorder—oral naltrexone and acamprosate—are not difficult for a primary care physician to learn and prescribe. Moreover, the brief counseling that goes along with these pharmaceutical treatments does not differ from the counseling that is given with high blood pressure medication. In the case of heavy drinking, counseling would include asking people if they are continuing to drink heavily, and if so, why, and what challenges they are facing in cutting back on their alcohol consumption. If they have had some successes, counseling would include congratulating them.

Saitz pointed out that every primary care clinician makes referral decisions based on their own expertise and experience. For example, a clinician might have expertise in treating cardiac disease and have a high threshold to refer a patient to a specialist, but that same clinician may feel uncomfortable treating someone with diabetes and refer them to a specialist right away. The same can be true with alcohol use disorder and OUD.

One factor that goes into whether to make a referral or not, added Saitz, is the satisfaction providers get from caring successfully for their patients. A survey he and his colleagues conducted two decades ago asked primary care doctors and some nurse practitioners if they were satisfied caring for people with diabetes, high blood pressure, alcohol use disorder, and SUDs. The results showed that the respondents were least satisfied caring for patients with SUDs, moderately but still not so well satisfied taking care of patients with alcohol use disorder, and very satisfied taking care of patients with high blood pres-

sure. It is unclear why this was the case, given that some of the most satisfied primary care clinicians he has met over the past decade have been those that began prescribing buprenorphine for OUD. “I have had people come up to me surprised at how happy and excited they were taking care of patients with opioid use disorder, and they would have never predicted that,” said Saitz.

Question and Answer Session with Webinar Participants

The first two questions asked for ideas on how to make care more patient-centered and focus on what patients want so they feel heard and respected. Saitz responded that when presenting a diagnosis, the clinician should talk to the patient to find out how the diagnosis is impacting their life. In the case of alcohol dependence, the patient might identify the consequences related to their drinking. The clinician might then turn the discussion to what the patient might want to change, using motivational interviewing techniques that help the patient feel listened to and respected (Morgenstern et al., 2012). He noted that emerging evidence suggests that many people can perceive and experience improvement in important outcomes (Kuerbis et al., 2014; Tucker et al., 2020) while continuing to consume alcohol. “They can reduce their drinking substantially to the point where they are satisfied that they have achieved a good outcome, that they feel good, that their health-related quality of life is better,” said Saitz. Chwastiak added that focusing on patient preferences and their perceptions of potential benefit from treatment is also important for treatment of depression.