3

Management Practices Within NNSA

Strong management practices, such as disciplined planning and budgeting and a clear line-management structure and decision making, are foundational to the National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA’s) success now and into the future. Thus, these practices constituted a large focus of this panel’s work. Further, the panel is convinced that NNSA’s ability to achieve lasting improvements in governance and management also requires a change in the organization’s culture. The panel focused on the following management activities, which largely align with the characteristics of “high-reliability” organizations identified in the Augustine-Mies report:

- Strategic planning,

- Integration of functional support with mission execution,

- Risk management,

- Workforce management,

- Planning and budgeting capabilities and processes,

- Budget and reporting classification codes, and

- Program management.

Although the Augustine-Mies panel found at the time of its study that NNSA lacked “effective management practices” in a number of areas, this panel has observed that NNSA has taken multiple actions since then to begin addressing these problem areas and to improve operations and administration across the enterprise. The following examples illustrate some of the efforts that have been completed or are currently under way:

- Three strategic documents issued in 2019 by the Administrator effectively set forth goals, objectives, and a vision for the future of the nuclear security enterprise. The documents emphasize

- The laboratory/plant/site strategic planning process contributes to progress on organizational and mission alignment. The timing of the process has been shifted to better align with the budget-building process, and the plans themselves align with NNSA’s strategic documents.

- In 2017, in response to the Augustine-Mies report and other recommendations, NNSA developed and began to implement a site governance peer review process. These peer reviews are part of NNSA’s effort to improve oversight of the laboratories, plants, and sites, with a focus on clarifying roles, responsibilities, and expectations, and increasing reliance on management and operating (M&O) contractor assurance systems for oversight. The peer reviews are generally viewed as a useful and successful process by both federal and M&O participants.

- Since 2017, NNSA has employed collaborative, data-driven processes to prioritize infrastructure investments based on a number of criteria, including importance to mission, safety, security, and cost. NNSA has catalogued its assets, evaluated their condition, and established a priority rating for needs to be addressed in its annual Master Asset Plan. In addition, an Infrastructure Modernization Initiative was launched in December 2017 with the purpose of reducing deferred maintenance and repair needs by 30 percent by 2025.

- In the first 2 years after the Augustine-Mies report, the Department of Energy (DOE) reestablished the Laboratory Operations Board, created a Laboratory Policy Council and Government Executive Steering Committee, and established a number of joint task forces of Chief Operations Officers, Chief Financial Officers, Chief Information Officers, and other leaders from headquarters and the M&O facilities to work together on common management challenges.

- NNSA has established an NNSA-wide team focused on employee empowerment. Decades of research have shown that federal employee engagement is linked to organizational health and performance.1

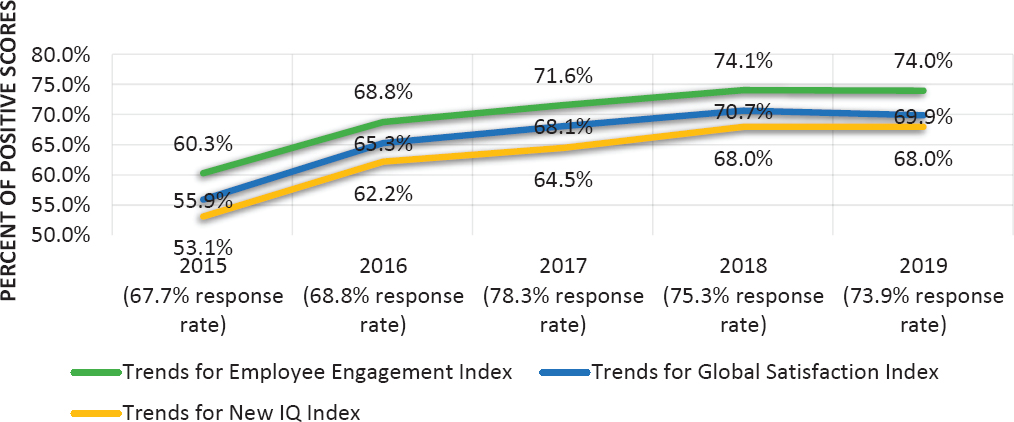

- Based on publicly available results from the annual Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS), overall morale (satisfaction and engagement) among NNSA federal employees notably improved from 2015 to 2019, as shown in Figure 3.1.

in several places that they pertain to the entire enterprise, and they make clear the aspiration of being a single team. Overall, the documents’ language regarding culture (including values and behaviors) and the importance of governance and management is promising.

These developments, and those detailed below, are examples of how NNSA has begun to take a strategic and comprehensive approach to the governance and management of the enterprise.

While NNSA has made substantial progress, the panel believes that the agency still has some organizational characteristics—such as lengthy decision-making processes, burdensome regulations, and risk aversion—that hamper its ability to meet its ambitious mission. For example, while most people the panel interviewed indicated that they or their office have the authority to make the decisions necessary to do their work, the panel also heard complaints about decisions at the headquarters level taking too long (e.g., in the pit production case study discussed in this chapter). This comes across as a lack of urgency and can impact schedules.

In addition, leadership commitment, measuring and communicating success, and institutionalizing change will be necessary to maintain momentum and sustain progress. Most importantly, NNSA needs to continue to make specific changes, such as those discussed in this chapter, as it continues its journey toward a workplace culture that emphasizes performance, credibility, and accountability.

___________________

1 See, for example, National Academy of Public Administration, 2018, Strengthening Organizational Health and Performance in Government, Washington, D.C.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

NNSA has been working to strengthen strategic planning both enterprise-wide and at the levels of laboratories, plants, and sites. It undertook a lengthy enterprise-wide strategic planning process in 2018–2019 that resulted in the three 2019 strategic documents mentioned earlier, the Strategic Vision, Governance & Management Framework, and Strategic Integrated Roadmap 2020–2044.2

Some specific aspects of those 2019 documents are particularly noteworthy. Placement of the agency’s mission statement front and center on the Strategic Vision cover is an effective way to communicate leadership’s focus on that mission. The “mission priorities” in the document are long-term and strategic, and each mission priority includes “mission milestones.” The Framework effectively sets out the Administrator’s governance and management priorities (e.g., clear roles and responsibilities and risk management) and includes an appendix detailing expectations. The Roadmap graphically presents mission priorities and goals through 2044. A number of leaders, midlevel managers, and staff from across the enterprise have told the panel that they are supportive of the documents—in particular, most who have seen it say that they can look at the Roadmap and see where their organization fits into it. As discussed below, these documents have the potential of serving as the basis for change and creating unity across NNSA and the enterprise.

The process for developing the documents was also a valuable step in governance and management reform. The Strategic Vision was developed with input from a variety of stakeholders; the panel understands that leaders from headquarters, NNSA field offices, and M&O partners had varying opportunities to provide input, and some Department of Defense (DoD) personnel were briefed on the Strategic Vision and given an opportunity to provide feedback before it was finalized. This inclusive process was

___________________

2 National Nuclear Security Administration, 2019, Strategic Vision: Strengthening Our Nation Through Nuclear Security, Washington, D.C.; National Nuclear Security Administration, 2019, Governance & Management Framework, Washington, D.C.; and National Nuclear Security Administration, 2019, NNSA Strategic Integrated Roadmap 2020–2044, Washington, D.C.

at least as important as the documents themselves: it contributes to relationships and trust across the enterprise and created buy-in for change from key leaders and stakeholders, thus creating greater unity around the mission.

The challenge will be to identify and put in place specific actions that carry out the vision in these documents—to operationalize them. The recommendations in Chapters 3–5 of this report are intended to help in that. One of NNSA’s initiatives to follow up on the release of the documents was to organize in fall 2019 almost 40 employee focus groups to solicit information and ideas related to improving NNSA governance and management. The focus groups were facilitated by an independent management consulting firm, and each consisted of a mix of individuals from across the enterprise. The participants had varying levels of seniority and lengths of tenure and were drawn from both programmatic offices and functional offices, and from NNSA and its M&O partners; none of them was a member of the Senior Executive Service (SES) or a political appointee. The results of the focus groups were presented to the heads and deputy heads of NNSA’s offices at a governance and management workshop in late January 2020 and to senior staff members at a leadership retreat immediately following. The panel was told that focus group results and feedback from those top leaders are being combined with lessons learned from the site governance peer reviews conducted at each laboratory, plant, and site and input from the Governance Executive Steering Committee to guide next steps, including developing a Governance and Management Action Plan to implement principles in the Strategic Vision and Governance & Management Framework.

The panel was recently told that NNSA is beginning a Strategic Risks Study to improve enterprise-wide strategic planning. The purpose of the study is to identify and examine anticipated external threats (and opportunities) over the next 25 years and determine how they could impact NNSA’s mission space. The initial focus is on emerging scientific capabilities and new and potentially disruptive technologies. The study will draw on ongoing and recent strategic planning, including at the program level, and results will feed back into the laboratory, plant, and site strategic planning cycle and the budget process. NNSA will also use the study to identify gaps in NNSA strategic planning and risk analysis.3

Starting in 2016, NNSA provided guidance for a strategic planning process for its laboratories that was adapted from the process used by DOE’s Office of Science. The goal of the guidelines was to make the plans more strategic than had previously been the case and to reduce data reporting requirements. Each year since then, NNSA has improved on the guidelines and process with the goal of being more strategic and inclusive:

- Expanded the process to include plants and sites, as well as laboratories;

- Linked the process to NNSA’s strategic documents by, for example, directing the laboratories, plants, and sites to describe how their unique capabilities further the priorities in the Strategic Vision and Strategic Integrated Roadmap;

- Updated and improved the guidance to be less operational;

- Included more key headquarters personnel and leadership from other sites when strategic plans are briefed to NNSA headquarters;

- Provided the leadership of each laboratory, plant, and site an opportunity to brief the Administrator in a separate meeting;

___________________

3 National Nuclear Security Administration, 2019, G&M Newsletter 1(3), and interviews with the NNSA Office of Policy and Strategic Planning.

- Transitioned from an annual to an every-other-year process (which also helps to ensure that the plans are more strategic; planning that is done on an annual basis tends to be more tactical than strategic); and

- Lengthened the time frame of the plans from 10 to 25 years.

In addition, in 2020 a team of M&O leaders participated in the revision of the annual guidelines; in the recent past, the M&Os did not see the guidelines until they were issued. These developments have supported greater mission alignment and are helping to improve communication and build trust across the enterprise.

INTEGRATION OF FUNCTIONAL SUPPORT WITH MISSION EXECUTION

The Augustine-Mies report noted a perceived lack of a mission-driven culture and unity around the mission across the nuclear security enterprise. Specifically, it mentioned a lack of understanding of roles and responsibilities among DOE, NNSA headquarters, the field offices, and the M&Os. In addition, functional support organizations often saw their role as enforcing compliance with rules and regulations rather than enabling the mission, resulting in them operating somewhat independently of mission execution offices.4

To clarify roles, responsibilities, authorities, and accountability, NNSA issued Supplemental Directive 226.1B on “NNSA Site Governance” in 2016.5 The current Administrator has further clarified roles, responsibilities, authorities, and accountability through the revised NNSA Supplemental Directive 226.1C (issued in 2019) and in the “Corporate Expectations” appendix of the Governance & Management Framework.6 In general, leaders and staff across the enterprise say that roles, responsibilities, authorities, and accountability are clearer now than 5 years ago.

SD 226.1C also promotes functional and mission execution integration. The directive explicitly states that functional managers are “mission enablers.” Former Administrator Klotz changed the reporting relationship so that field office managers report directly to the Administrator. That arrangement, which continues, facilitates those managers’ participation in program discussions, and in general the field office managers accept that their primary role is to support NNSA mission execution. Through SD 226.1C, the Administrator also established field office positions that are explicitly charged with serving as liaisons to certain NNSA programs, with the goal of promoting better integration across the enterprise. And as part of the Administrator’s realignment initiative of 2019, the planning, programming, budgeting, and evaluation (PPBE) professionals in NNSA’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) are matrixed to NNSA’s programs and field offices. Overall, the current NNSA Administrator has widely communicated the goal of “Getting to Yes,” which signals to field and functional offices that they are expected to solve problems in furtherance of the mission (while also ensuring compliance with laws and regulations), rather than to strictly enforce compliance.

___________________

4 Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise, 2014, A New Foundation for the Nuclear Enterprise: Report of the Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise, http://cdn.knoxblogs.com/atomiccity/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/12/Governance.pdf, p. 23.

5 See NNSA SD 226.1C, NNSA Site Governance, https://directives.nnsa.doe.gov/supplemental-directive/sd-0226-0001c/@@images/file.

6 See NNSA SD 226.1C, NNSA Site Governance, https://directives.nnsa.doe.gov/supplemental-directive/sd-0226-0001c/@@images/file, and NNSA, 2019, Governance & Management Framework, Washington, D.C.

An example of how roles and responsibilities are being clarified, and functional support and mission are being integrated, is the Administrator’s designation of the Office of Defense Programs as the account integrator for NNSA’s weapons activities budget. In this role, the Office of Defense Programs coordinates and prioritizes the activities and projects necessary to complete program goals. The functional offices involved (Office of Safety, Infrastructure, and Operations and Defense Nuclear Security) embrace that their roles are to support those programmatic needs. To assist in this coordination, it is now common practice for functional office representatives to attend weekly staff and other program office meetings, helping to facilitate in their supportive roles.

Although M&O and field office personnel have told the panel that most of their relationships with functional offices are good or improving, the panel has heard mixed reactions about interactions with NNSA’s Office of Acquisition and Project Management (NA-APM).7 The concerns have included a lack of risk-based decision making and an overemphasis on compliance. While it is possible that such comments reflect an impatience by program offices to get their projects approved and under way, the panel sees this tension as indicating that more work is needed to improve the understanding of NA-APM’s role and working relationships. The panel notes that rotational assignments are a helpful means of improving mutual understanding of roles and responsibilities.

In sum, NNSA has made significant changes and implemented initiatives to clarify roles and responsibilities and to improve functional support and mission execution integration, but this is a continuing challenge and it is too early to tell how effective some of the changes will be. It is also unclear whether some of the changes have been adequately institutionalized to be sustained over time.

Recommendation 3.1: National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) leadership should build on progress made on clarifying roles, responsibilities, authorities, and accountability by improving its communications about and enforcement of the relevant policies.

- To clarify the roles of functional support offices vis-à-vis mission execution, NNSA leadership should promulgate policies that engage support-office personnel early in mission-related planning in order to smooth the process of “Getting to Yes,” thereby enabling mission accomplishment.

- To increase the shared understanding of roles and responsibilities throughout the enterprise, NNSA leadership should expand programs for rotation of personnel between federal and nonfederal positions, as well as between headquarters and field offices. This expansion should take the form of making such opportunities more widely available and of longer duration. Consideration should be given to requiring rotational assignments prior to promotion to senior NNSA positions.

RISK MANAGEMENT

In the Governance & Management Framework, NNSA signaled that improving risk management is a priority by describing policies and initiatives that have been completed or are under way:8

___________________

7 The Office of Acquisition and Project Management is focused on construction project delivery and acquisition improvements and provides independent counsel to ensure that NNSA implements federal acquisition and construction project management policies and regulations.

8Governance & Management Framework, pp. 10–11.

- The Quality Management System policy9 includes risk management expectations.

- Risk reduction programs and processes have been designed to identify, track, and remove or abate obstacles to achieving mission and improving mission success, while providing appropriate oversight.

- Best practices and lessons learned are shared through processes like the site governance peer reviews.

- An enterprise risk management approach based on risk management principles and best practices is being developed. It is intended to cover risk acceptance, risk acceptance roles and responsibilities, and how to appropriately balance the accomplishment of mission demands and satisfaction of safety and security requirements.

Unfortunately, these efforts have not yet changed a culture of risk aversion—evidenced, for example, by choices in how laboratory safety is monitored and controlled—that, to some leaders and personnel, appears deeply rooted. The panel heard a variety of perspectives on risk aversion at all levels and across the enterprise. Some staff members have seen examples of the enterprise becoming less risk averse and having improved risk management, while others believe there has been no change or that the enterprise has become even more risk averse. This mix of views persisted with little change over the course of the panel’s study and were not dependent on type of personnel (federal or M&O) or location.

It is important to note that most M&O personnel who believe that the enterprise is overly risk averse are uncertain of the source, and some attributed it to the M&Os themselves. However, even in cases where this is true, NNSA has a strong influence on the overall environment, which could be encouraging the M&Os to be overly risk averse. Furthermore, expectations developed through years of compliance-focused oversight take a long time to undo. Many of those who placed the blame on NNSA indicated that the program offices were much more risk accepting than functional offices.

Those who view risk aversion as a persistent cultural problem believe that it creates obstacles to mission success as it

- Undermines trust, transparency, agility, and innovation;

- Leads to burdensome practices, like data calls and regulations;

- Pushes decision making higher up the chain than should be necessary, thereby lengthening the decision-making process; and

- Results in too many layers of oversight and requirements for a large number of signatures, slowing processes.

Actions that could contribute to addressing risk aversion by NNSA and its M&O partners are discussed in Chapter 4, both in Recommendation 4.1 on eliminating burdensome practices and in Recommendation 4.2 on maximizing value from the federally funded research and development center (FFRDC) relationships.

MANAGING THE FEDERAL WORKFORCE

The Augustine-Mies report stated that NNSA’s federal workforce lacked some necessary technical and managerial skills, particularly in the areas of cost and resource analysis and program management. (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of M&O workforce issues.) Further, NNSA lacked the personnel pro-

___________________

9NNSA Policy Letter, NAP-26B, January 10, 2017.

grams, such as career development and rotational assignments, needed to build a skilled and experienced federal workforce. Creating and sustaining a personnel management system to build the needed culture, skills, and experience is a vital component of governance reform.

The panel has seen substantial activity related to these and other human capital areas, such as hiring, innovating to speed up the security clearance process, and increasing employee engagement. NNSA has established or expanded multiple programs and initiatives with the goal of having talent in the right numbers with the right skills in the right locations.

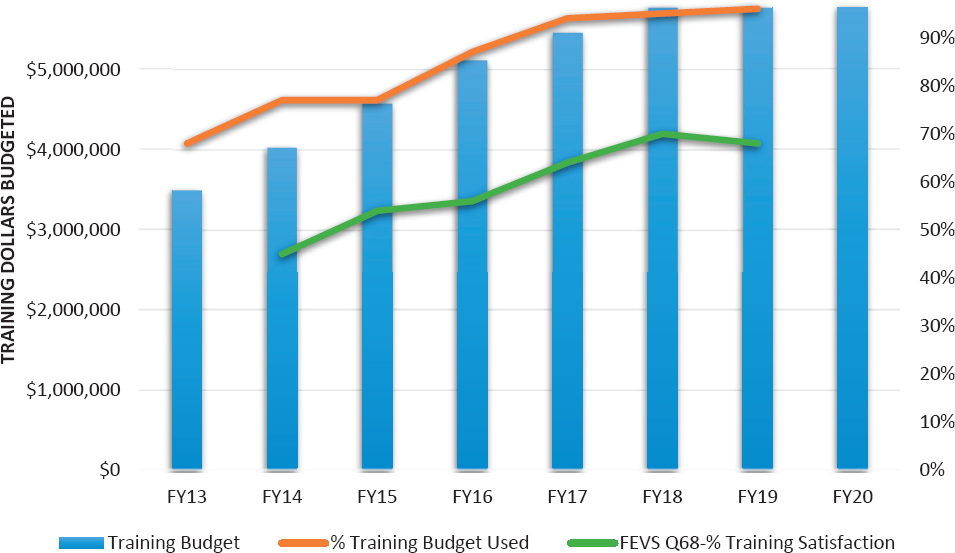

In recent years, NNSA has increased its emphasis on training and development for the federal workforce through the Learning and Career Management Center, which has become an active force in the organization. As shown in Figure 3.2, between FY 2013 and FY 2019, NNSA’s training budget increased from $3.5 million (only 68 percent of which was used) to $5.8 million (of which 96 percent was used). In FY 2014, 40 percent of employees developed and got approval for their individual development plans, whereas in FY 2019, 90 percent developed and got individual development plans approved. And employee satisfaction with training, as reported in FEVS results, sharply rose from 45 percent in FY 2014 to 68 percent in FY 2019. Overall, since 2013, NNSA’s training and development ranking across the federal government moved from the bottom 25 percent to the top 15 percent.10

The Learning Center also supports rotation assignments, which were somewhat limited in 2018: eight people completed 90-day rotations from headquarters to field office or vice versa. Given both the Augustine-Mies and this panel’s findings that M&O leaders and staff, in particular, believe that

___________________

10 NNSA, “Learning and Career Management: 2019 Year in Review,” National Nuclear Security Administration, Washington, D.C., p. 4.

headquarters staff do not fully understand the work and the challenges faced in the field, the panel supports NNSA’s plans to expand the program of rotational assignments of NNSA personnel with the M&Os and vice versa. However, the panel also heard that M&O and field office personnel often do not understand the pressures faced by headquarters, and that 90 days is not enough time to learn a new organization and job (see Recommendation 3.1).

Learning Center plans for 2020 include clarifying competencies and career paths for multiple mission-critical occupations, including program managers, and developing a “talent development strategic plan” that aligns with overarching NNSA strategies.

In 2019, NNSA significantly ramped up its hiring. Early in her tenure, the Administrator determined that traditional hiring methods were not resulting in NNSA successfully filling its open slots, and in addition, NNSA was not using all of its allocated positions. One initiative to address this problem was to hold enterprise-wide job fairs. The first such fair was successfully held in January 2019 in Washington, D.C. Importantly, at these fairs individuals can apply for jobs with NNSA or submit resumes with any of NNSA’s M&O partners. Two other such job fairs have been held since then, including a virtual job fair held during the coronavirus pandemic. Further, NNSA established the nuclear security enterprise Educational Partnership Consortium, which focuses on forming and sustaining strategic partnerships with educational institutions.

The length of time it took to get a security clearance was a long-standing problem for both NNSA and M&O personnel. NNSA’s Office of Defense Nuclear Security worked with DOE and the Office of Personnel Management to reconfigure and streamline its own activities, cutting the length of the process in half, from 6–12 months to 3–6 months. NNSA leaders report that progress in expediting clearances has saved thousands of manpower days.

NNSA has also established a team focused on employee empowerment that monitors and responds to feedback received through the FEVS. There is a strong correlation between employee engagement and organizational health, including performance outcomes like productivity, safety, and quality.11 By using the FEVS to identify areas on which to improve, NNSA has successfully increased FEVS scores since 2015. However, the FEVS surveys only federal employees, which represent just 3.3 percent of the total enterprise. The focus groups that NNSA held in 2019, which included M&O employees, were an invaluable opportunity for NNSA to collect data on M&O workforce satisfaction, engagement, and perspectives, and the panel encourages NNSA to continue this practice (M&Os might also benefit from holding focus groups). However, it is not feasible or practical for NNSA to hold enough focus groups to include a representative sample of the more than 55,000 M&O employees. Most M&O partners survey their employees (although not necessarily annually, and not with a standard set of questions), but it is unclear whether or how the questions compare with the FEVS, and the results are not shared with NNSA. As a result, NNSA does not have a full understanding of attitudes and engagement throughout the enterprise or insight about specific concerns. Because the M&O workforce is critical to the NNSA mission, a general understanding of M&O workforce perspectives and engagement can provide important input into governance and management decision making and priority setting.

The panel made a recommendation about this in its second report,12 from 2018, and offers a variant here:

___________________

11 J.K. Harter, F.L. Schmidt, S. Agrawal, S.K. Plowman, and A. Blue, 2016, The Relationship Between Engagement at Work and Organizational Outcomes: 2016 Q12® Meta-Analysis: Ninth Edition, http://www.workcompprofessionals.com/advisory/2016L5/august/MetaAnalysis_Q12_ResearchPaper_0416_v5_sz.pdf, pp. 2–3.

12 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2018, Report 2 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., p. 3.

Recommendation 3.2: The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) should gain a better understanding of attitudes and engagement of the entire enterprise workforce. It should require all of its management and operating (M&O) partners to conduct regular employee surveys, preferably including some questions that are found on the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS). NNSA should require the M&O partners to provide it with the responses, properly anonymized, to at least those latter questions.

BUDGET, COST, AND SCHEDULE CONTROL

The Augustine-Mies report as well as various Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports over the past decade have been highly critical of NNSA’s ability to estimate costs and execute projects on budget and according to schedule. Problems cited include numerous instances of wildly inaccurate estimates involving not only construction of facilities, such as the Y-12 highly enriched uranium processing facility, but also for the costs for Life Extension Programs, such as the B61. Some cost estimates for major NNSA programs and projects were as low as half of an estimate produced using best practices; an outlier was low by a factor of 6. All too frequently, the discoveries of these misestimates were not communicated to either the Congress or to DoD customers in a timely fashion, severely undermining both trust and credibility.

In response to these criticisms, former Secretary of Energy Moniz in 2015 initiated major changes to project management policies under DOE Order 413.3B, which governs Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets.13 Those changes were aimed at ensuring clear roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities among the various participants in the project-planning process and ensuring that an Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) be conducted independent of the organization responsible for managing the project. NNSA is implementing a new project delivery model that involves assigning a federal project director earlier in the program development process, with the ultimate goal of producing more reliable analyses of alternatives and baseline cost and schedule estimates. However, the GAO still lists NNSA contracts and major projects with budgets of $750 million or more on its 2019 high-risk list.14

NNSA’s NA-APM was created in 2012 specifically to manage federal acquisition and project management processes for major construction projects. NA-APM has continued to build on the changes described above for all major projects within NNSA. In addition to managing the implementation of DOE Order 413.3B and its NNSA complement, NA-APM has led careful reexaminations of major projects that were experiencing significant cost and schedule problems, such as the Uranium Processing Facility at the Y-12 Plant and the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Facility at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL).

These reviews involved experts from across and outside the DOE complex in rigorous AoA examinations. The results often have been substantial restructuring of the original project concepts, leading to major redesigns, reuse of existing facilities, and resizing of new construction requirements. The re-scoping of such projects has significantly reduced the total budgets for those projects and increased the feasibility of successfully completing them. In the two instances cited above, the total budgets have been reduced by approximately 50 percent from the earlier levels and the projects have been managed on schedule and on budget for more than 6 years.

___________________

13 See DOE O 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets, http://www.directives.doe.gov/directives-documents/400-series/0413.3-BOrder-b/@@images/file.

14 GAO, 2019, High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas, Government Accountability Office, Washington, D.C.

In addition to such high-profile cases, NA-APM oversees the application of the 413.3B process for many smaller projects every year. In interviews with experts from GAO and elsewhere, the panel gathered assessments that this management approach has led to some improvements in cost and schedule performance over the past 5 years. The improvements have been attributed to the use of independent cost estimates, peer reviews of designs, the AoA process, and the discipline of waiting until designs are 90 percent complete before beginning construction.

In 2014, NNSA established an Office of Cost Estimating and Program Evaluation (CEPE). This office was modeled after DoD’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office, which is charged with providing independent analytic advice to the Secretary of Defense on all aspects of DoD programs along with independent estimates of costs for major programs. CEPE’s initial focus was on Life Extension Programs and the budget buildup process, although it has since expanded its coverage to include independent reviews of AoAs, which now comprise a significant portion of its workload. Its staff over the past 5 years has grown from 2 full-time employees and 3 contractors to 16 full-time employees and 7 contractors. These are cost estimators and program evaluation specialists, many from DoD. While CEPE is not the ultimate decision maker on costs, it is charged with reviewing and commenting on cost estimates of Life Extension Programs before each acquisition milestone. Most recently, it has also been put in charge of providing independent cost estimates of construction projects.

As CEPE’s responsibilities have increased, the panel was told that it has developed a solid working relationship with NA-APM while reviewing the budget profile for construction projects and likewise with NNSA’s Office for Safety, Infrastructure, and Operations with which it partners on some work for the annual budget build. The panel heard that CEPE has had some challenges in working with NNSA’s cadre of PPBE specialists (established in 2019 within NNSA’s Office of Management and Budget), particularly when dealing with the review of AoAs and the budget-build process.

While the Administrator and Congress are fully aware of CEPE’s cost projections, the program offices’ estimates are more often used when funding requests are made. The panel was told that those latter estimates may reflect the willingness of the Administrator and the head of Defense Programs to accept a higher level of risk.

For CEPE to be most useful, it will need to cement the relationships mentioned above as well as with the program offices, building trust such that offices throughout NNSA come to recognize the skills that it brings to the process and place increasing confidence in the accuracy of CEPE’s projections.

The GAO in various reports has already noted improvements in NNSA’s documentation of costs for construction projects and complimented NNSA on the cancellation of the Mixed-Oxide Program (MOX) at Savannah River (SRS). However, the panel is unclear about the handling of situations where CEPE’s cost estimate differs materially from the estimate produced by the NNSA program offices. In at least one case of which the panel was told, cost estimates from a program office were adopted over a quite different CEPE estimate. More information about how differing estimates are reconciled would be helpful to external stakeholders.

Recommendation 3.3: The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) should enforce its policies for estimating and controlling budget, cost, and schedule for major programs and capital projects. To enhance the credibility of program plans and budget estimates, NNSA should improve its process for addressing differences in cost estimates from Cost Estimating and Program Evaluation (CEPE) and program offices to include providing accessible documentation that reconciles the differences and makes clear the provenance of the estimate used in the budget.

The reorganization of NNSA’s PPBE capabilities is another step designed to provide more disciplined planning and budgeting. As mentioned briefly above, some 56 individuals were reassigned in 2019 from disparate program and functional offices across NNSA to form a unit of PPBE specialists within NNSA’s Office of Management and Budget. By assembling such a unit, the professionalism of PPBE specialists can be increased, and their shared insights make it more likely that cost estimates across NNSA will be comparable and that these specialists can be reassigned as workload shifts. Three internal NNSA policy documents were released in December 2019 to codify key elements of this reform.15 This change is still too new for the panel to be able to assess its effects.

BUDGET AND REPORTING CLASSIFICATION CODES

Budget and reporting (B&R) classification codes are required by Congress and NNSA for tracking spending and levels of effort.16 The Augustine-Mies and Commission to Review the Effectiveness of the National Energy Laboratories (CRENEL) reports both noted a proliferation of B&R codes at NNSA that imposed undue burdens and constraints on the ability of NNSA and its M&O partners to flexibly manage their work.17 However, some of this compartmentalization may be needed to answer legitimate management or congressional questions or to otherwise gain transparency into the operations by capturing how funds are spent at some level of granularity. The additional detail can also help the enterprise evaluate its performance.

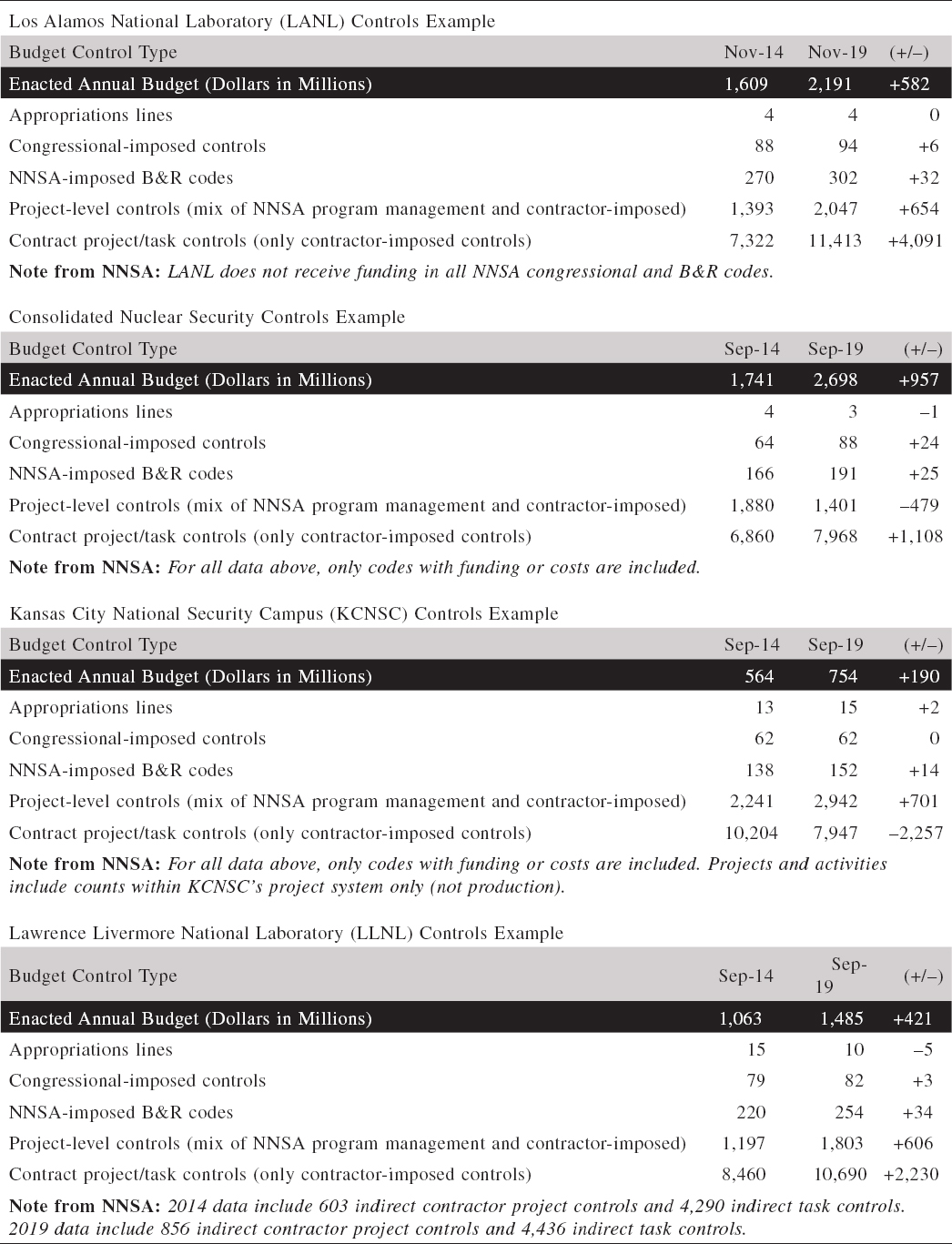

Table 3.1 displays how the number of budget controls has changed over the course of 5 years at two of NNSA’s laboratories and two of its plants. The number of congressionally imposed control levels has increased little, if at all. However, at the two laboratories the number of budget control codes imposed by NNSA and the laboratories themselves has increased significantly, although generally in proportion to the increase in overall budgets. There has been a reduction in project and activity codes at the two M&O plants shown.

Table 3.1 shows that, contrary to what many in the enterprise believe, the number of budget control categories is not driven by Congress but rather is primarily the result of behavior within NNSA and at the laboratories, plants, and sites. (However, the panel was told recently by a senior official at NNSA that the agency maintains some budget categories to provide more transparency to Congress.) Some budget categories are for data and reporting purposes and therefore do not act as “control” points that constrain the work by requiring approvals for funding increments. Without further examination of that point, and of how these categories do or do not impact day-to-day management, it is not possible to determine whether they are unnecessarily burdensome.

NNSA is undertaking a multiyear financial integration project to develop and apply a cost-collection tool intended to enable direct and indirect costs to be determined and compared across all sites and

___________________

15 NAP 130.1A, Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Evaluation (PPBE) Process, https://directives.nnsa.doe.gov/nnsa-policy-documents/nap-0130-0001a; ACD 413.1, Centralizing Cost Estimating Activities in the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), https://directives.nnsa.doe.gov/advance-change-directives/400-series/acd-0413-0001; and ACD 413.2, Centralizing Analyses of Alternatives Studies in the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), https://directives.nnsa.doe.gov/advance-change-directives/400-series/acd-0413-0002.

16 Budgetary categories and controls define blocks of appropriated funding and specify the purposes for which such funding may be used, such as for labor or construction under particular programs or at particular sites. Such controls may also limit use of the funds to particular fiscal years or other periods and may impose other limits on permissible use. Moreover, spending must be reported in terms of these categories.

17 See Commission to Review the Effectiveness of the National Energy Laboratories, 2015, Securing America’s Future: Realizing the Potential of the Department of Energy’s National Laboratories: Final Report of the Commission to Review the Effectiveness of the National Energy Laboratories, Volume 1: Executive Report, http://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/10/f27/Final%20Report%20Volume%201.pdf, pp. 31–34 and Recommendation 14. Also see Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise, 2014, pp. 48–49.

programs.18 According to some officials at both NNSA and its M&O partners, that initiative will provide greater transparency into how funds are spent and thereby enable NNSA to consolidate its reporting categories down to fewer B&R codes for each congressional control category.

MAJOR PROGRAM MANAGEMENT, AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIT PRODUCTION PROGRAM

To gain greater insight about program management at NNSA, the panel conducted a case study of NNSA’s very important and high-profile plutonium pit production program. Appendix C describes in detail the program management structures and processes—roles and responsibilities, coordinating bodies and councils, and management and budgetary authorities. The appendix also presents the program structures and processes by level: strategic-level management, operational-level management, and field-level management.19 The panel evaluated this structure’s capability for providing strong and effective management, using the attributes laid out in the Augustine-Mies report as a guide.

That report had the following to say about program management:

An essential step toward creating a culture focused on mission performance and accountability is to establish program managers (PMs) for major programs and construction projects, who have sufficient authority, resources, and accountability to meet mission deliverable objectives. Delegating control to these PMs for relevant funding would serve to transform program managers from weak coordinators—who must negotiate for support from the campaigns and mission-support staffs—to resource-owning managers. These officials would serve as the focal point for planning and executing their programs, and become the “go-to” individuals for solving problems and resolving issues. Program managers should also have approval authority for all personnel assigned to their projects and be responsible for personnel evaluations. To exercise their authorities effectively, these PMs must have proven technical, managerial, and leadership skills.20

On the positive side, the panel found that several aspects of the management of the pit production program are working well:

- Strategic-level management

- NNSA’s top leadership is firmly committed to meeting the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) pit production goals through active and ongoing engagement.

- NNSA’s management structure appears to be effective in fostering communications and coordination.

- The Office of Defense Programs is now the account integrator for the Weapons Activity budget, which enables it to prioritize programs and projects and to identify and resolve disconnects between program and functional leadership.

___________________

18 The Government Accountability Office recently issued a report about NNSA’s financial integration effort: National Nuclear Security Administration: Additional Actions Needed to Collect Common Financial Data, January 2019, http://www.gao.gov/assets/700/696683.pdf.

19 Strategic-level management is the internal strategic decision maker and priority setter, as well as the external liaison for the pit production mission (the Administrator and Deputy Administrator of Defense Programs). Operational-level management is where day-to-day managerial and technical decisions are made. Field-level management is where plutonium pit production happens.

20 Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise, 2014, pp. 56–57; emphasis added.

-

Operational-level management

- The program manager for the pit production program, who is within the Office of Defense Programs, controls most of the financial resources needed for that program, including not only the funding executed by Defense Programs but also most of the funding that is executed by NNSA’s Office of Safety, Infrastructure, and Operations and Office of Security.

- Field-level management

- LANL has established an experienced leadership team with responsibility for producing pits at its facilities and has taken on the comprehensive responsibility to plan for and advise NNSA leadership on the execution of the overall pit production program.

- SRS is only 2 years into developing its pit production capacity. NNSA implemented a new project delivery model at SRS, establishing and involving a Federal Project Director earlier in the project planning process to improve program and project planning and coordination.

- Interviewees from NNSA, LANL, and SRS spoke highly about the cooperative, partnering relationship among themselves, as well as with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL).

While the program benefits greatly from strong leadership priority and engagement, at the operational management level, where day-to-day managerial and technical decisions are made, many of the Augustine-Mies principles for effective program management have not been adopted by NNSA. The program manager works through a matrixed structure, for which several other offices within NNSA—including NA-APM, NA-50, and NA-70—have designated individuals as representatives, but NNSA’s traditional matrix management approach does not give the program manager the greatest chance of success. The panel identified several specific weaknesses in the current approach:

- NNSA’s pit production program manager resides several levels deep in the NA-10 organization and is often outranked by the representatives from the functional communities whose activities he is responsible to integrate.

- The program manager has not had the resources necessary to assemble a core team of experts to lead the program.

- The program manager also relies heavily on the laboratories and plants for essential technical expertise.

- While these matrixed participants view the program as their “customer,” the pit production manager does not control the team responsible for the program, as the various functional representatives and experts do not report to him, nor does the pit production program manager participate in their employee performance reviews. Although considerable technical expertise resides at LANL (and LLNL), NNSA also relies on multiple external review boards for supplemental expertise, and consequently many decisions are made through a time-consuming consensus-building process, with the result that too many issues must be elevated to NA-10 for resolution.

For this program, NNSA has largely retained its traditional form of matrix management, which diffuses authority, slows decision making, and in NNSA has often proven unsuccessful in the past. Because of the way program authorities are distributed, decision making relies heavily on consensus building among major program stakeholders, as well as other external reviewers. When disagreements arise that cannot be resolved through negotiation, they sometimes need to be elevated. The panel heard of several instances in which the plutonium program office was not the final authority for making management decisions related to technical aspects of the pit production program, which slowed decision making.

All the participants in the pit production program with whom the panel interacted identified substantial risks in meeting the ambitious milestones and objectives for this program, and the panel believes that many of those risks could be better addressed by a program management structure providing stronger operational-level integration across the program. In agreement with the Augustine-Mies report, the panel advocates leveraging the proven attributes of successful program management structures.

Recommendation 3.4: The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) should ensure that the management structures for its major programs provide a high level of authorities and capabilities to one strong program manager so that program managers can serve as the focal point for anticipating and resolving issues in the execution of the program. As an example, the manager of the pit production program should be transitioned to have even stronger authorities and capabilities in order to maximize the program’s chances of success.

CULTURE CHANGE

Many of NNSA’s efforts to improve management practices have been tied to efforts to change culture and attitudes, including creating unity of the enterprise around the purpose/mission. An organization’s culture is defined as the shared values, assumptions, and beliefs that guide individual behavior and interactions. It is expected and appropriate for different organizations within the enterprise, especially the M&O partners, to retain their own cultures. However, there are broader enterprise attributes that should—or must—apply to all components of the enterprise and that govern how the different components behave and interact with each other. For example, a value being promoted by the Administrator is “One NNSA,” which means “having an effective, unified team working toward serving our Nation and accomplishing our vital mission.”21 This is unity of the community coming together around the common purpose. Unity does not imply absence of disagreement or conflict, or uniformity; rather, it implies a community that embraces the benefit of coming together to achieve a common purpose.

While change began under Administrator Klotz, the focus on culture change and unity has received added energy and emphasis by Administrator Gordon-Hagerty. The Strategic Vision, Governance & Management Framework, and Strategic Integrated Roadmap serve as the basis for change, with senior NNSA leadership driving change through regular communication regarding the importance and goals of the change. NNSA has also made several efforts to successfully engage stakeholders, including leaders, managers, and staff from across NNSA and the M&O partners, in providing input into and implementing change. The planned Governance and Management Action Plan is meant to build on such engagements.

The combination of laying out the vision and priorities for the enterprise, demonstrating and reinforcing leadership commitment, and building stakeholder engagement indicates that NNSA’s senior leadership recognizes that long-term success requires a commitment to changing the culture and attributes of NNSA to one that puts even greater value on performance, accountability, and credibility. Changing the culture creates an inherent preference toward those goals that positively affect how day-to-day decisions are made, and thus better enables the nuclear security enterprise to meet current and future challenges.

Leaders, managers, and staff across the enterprise indicated in interviews and discussion groups that they appreciate the Administrator’s emphasis on mission and communication about roles individuals have in achieving the mission. The Administrator’s insistence on always referring to the M&Os as “partners,” and never as “contractors,” is not only appreciated by M&O leaders and staff but also appears to be contributing to a shift in culture to one where NNSA and the M&Os have common goals and work in

___________________

21Governance & Management Framework, p. 7.

partnership to solve problems. Individuals at all levels of both NNSA and the M&Os describe a more trusting and less adversarial relationship than existed 5 years ago. Under the Administrator’s leadership, senior leaders at headquarters, field offices, and the M&O partners recognize that they have a role in communicating about and implementing change, and they have begun to do so.

The challenge now is for change to penetrate below the upper management layers of the organization. Panel discussions revealed that M&O personnel below the most senior levels are much less likely to be aware of the strategic documents or NNSA’s culture change initiatives. Few of the discussants involved have seen enough change in the behavior of NNSA midlevel managers and staff to conclude that prior relationships or practices have changed. Further, some NNSA employees report waiting for this change initiative to blow over, anticipating the all-too-real possibility of future leaders placing less emphasis on culture change and management reform—or even changing direction.

NNSA has not yet finalized and publicized measures (quantitative or qualitative) for monitoring progress in governance and management, or of cultural attitudes. It has not specified reliable methods to assess current steps, to identify what else is needed, or to determine whether current steps should be modified. Experience with large-scale change management has shown that developing and testing metrics is an iterative process that can extend over years.

NNSA has and is taking many specific steps that should help change its culture, as this chapter makes clear. However, while interviews with leaders and employees across the enterprise show progress, it is still too early to tell whether culture change will take hold and be “successful”: culture change takes several years and sustained attention. Further, change must be institutionalized so that it can survive changes in leadership, including holding people (and leaders) accountable for change. Although achieving greater unity around purpose may be achievable sooner, it too will take time to fully penetrate the enterprise.

There is currently no one person with the time, institutional seniority, and stature to shepherd the change initiative. The time, authority, and resources needed to fulfill that responsibility should not be underestimated. Resources include staff or contractors experienced in change management, communication, employee engagement, developing metrics, and institutionalizing change. The Office of Policy and Strategic Planning, which is in the Administrator’s front office, has led the effort to develop the strategic documents and has been tasked with spearheading communication about the documents and developing an action plan for their implementation. This small office has contracted with a management consulting firm that is providing support for governance and management reform. However, the office has experienced and continues to face fairly high turnover, potentially calling into question whether its focus and attention will be sustained. Therefore, the panel reiterates (with minor changes) a recommendation from its fourth report of early in 2020.22

Recommendation 3.5: The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) Administrator should promptly designate a career senior executive service member as the accountable change management leader to provide intensive and sustained attention to the challenges of institutionalizing governance and management reform. This leader should support the Administrator in developing continuous improvement strategies and implementation plans, leading continuous improvement processes, and ensuring that management metrics are developed and employed.

___________________

22 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2020, Report 4 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.