1

Introduction

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), established in 2000 by Congress as a semiautonomous agency within the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), traces its history back to the Manhattan Project in the 1940s. Today, NNSA leads a nuclear security enterprise that includes three national laboratories, several production facilities, and an experimental test site. NNSA’s mission is “to protect the American people by maintaining a safe, secure, and effective nuclear weapons stockpile; by reducing global nuclear threats; and by providing the U.S. Navy with safe, militarily effective naval nuclear propulsion plants.”1 The threats to U.S. national security have evolved significantly since the end of World War II, but the importance of nuclear security and thus NNSA’s role in protecting the country’s national security remains critical.

NNSA must accomplish its mission, which includes ensuring the availability of many unique intellectual and physical resources, while navigating the political winds that surround nuclear weapons issues and the accompanying variations in budget. The year 2020 brought with it the new challenge of continuing operations—which include major surges in requirements, deliverables, and personnel needed to respond to the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR)—amid a global pandemic. These circumstances heighten the need for a nuclear security enterprise that is “adaptive, agile, responsive, and resilient.”2

This report is the result of a study to evaluate the progress that DOE and NNSA have made over the years 2015–2020 in response to the 2014 final report of the Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise. That panel was co-chaired by Norman Augustine and Admiral Richard Mies and is often referred to as the “Augustine-Mies report.” The bottom line of that report was

___________________

1 National Nuclear Security Administration, 2019, Strategic Vision: Strengthening Our Nation Through Nuclear Security, Washington, D.C., http://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/05/f62/2019-05-06%20NNSA%20Strategic%20Vision.pdf; National Nuclear Security Administration, 2020, NNSA Strategic Integrated Roadmap FY 2020–FY 2045, Washington, D.C., front cover.

2 National Nuclear Security Administration, 2019, Strategic Vision: Strengthening Our Nation Through Nuclear Security, Washington, D.C., p. 1.

that “the existing governance structures and many of the practices of the enterprise are inefficient and ineffective, thereby putting the entire enterprise at risk over the long term” and that NNSA’s governance reform to that time “has failed to provide the effective, mission-focused enterprise that Congress intended.”3

The panel has witnessed improvements in the governance and management of the nuclear security enterprise over the course of its study. It has also seen improvements in relationships among groups within NNSA, as well as between federal employees and their partners at the laboratories, plants, and sites, and improved relationships with the Department of Defense (DoD). The panel is cautiously optimistic that, if NNSA continues to drive its messages about governance and management throughout the agency and builds on the specific improvements noted in this report, while measuring and institutionalizing progress made, it will be in a strong position to navigate future challenges.

ORGANIZATION OF THE NUCLEAR SECURITY ENTERPRISE

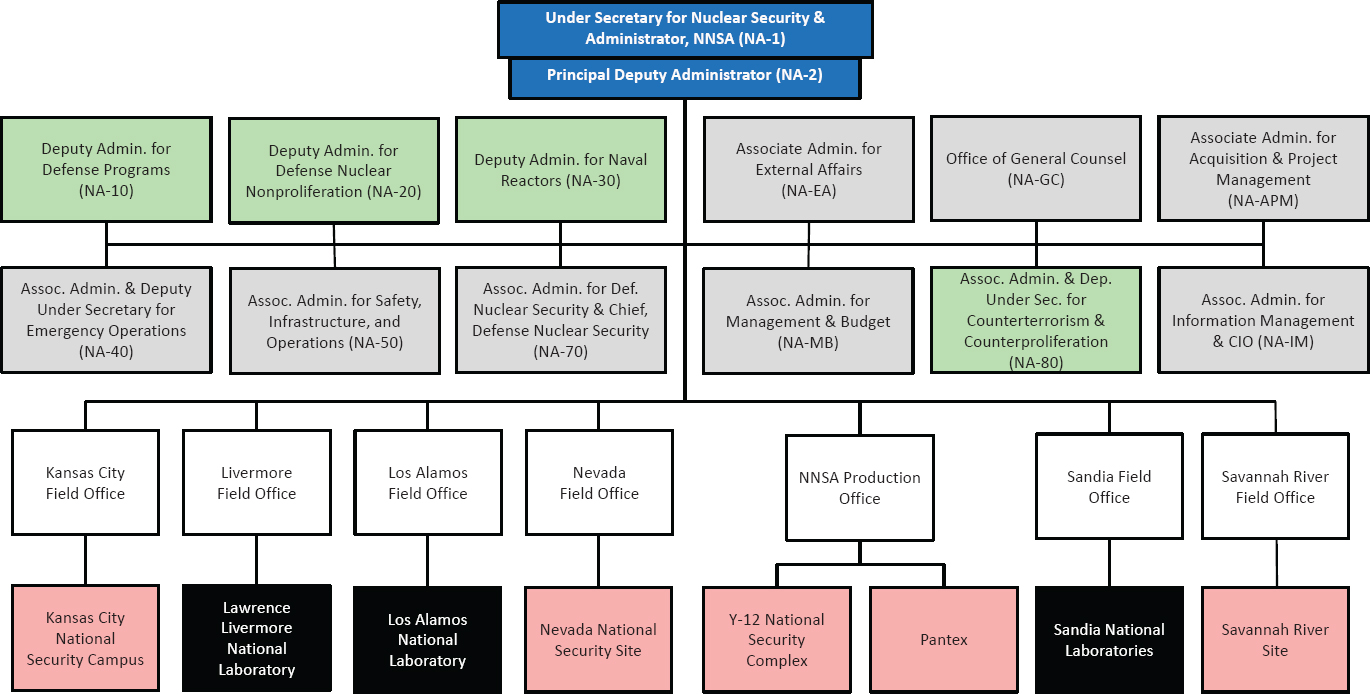

The nuclear security enterprise is large, complex, and geographically dispersed. Its components are shown in Figure 1.1. NNSA has four mission offices: Defense Programs, Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation, the Office of Counterterrorism and Counterproliferation, and the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program. Federal personnel are housed in 10 physical locations around the country including headquarters and seven field offices. NNSA has eight mission support offices, also referred to as “functional” offices.4

The bulk of the nuclear security enterprise, measured either by budget allocation or by the number of personnel assigned, comprises seven facilities run by management and operating (M&O) partners. Of these seven facilities, three are national laboratories that operate as federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs): Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), and Sandia National Laboratories (SNL, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Livermore, California). Three of the other facilities—Kansas City National Security Campus, the Pantex Plant, and the Y-12 National Security Complex—are highly technical production plants that do complex manufacturing and assembly/disassembly. The Savannah River Site produces tritium for warheads, and it will house one of two pit production facilities, the other being located at LANL. Also, the Nevada National Security Site serves multiple purposes, including as an experiment and test facility.5

The workforce of the nuclear security enterprise consists of about 1,900 federal employees and more than 55,000 employees of M&O partners. Most of the latter are employees of a laboratory, plant, or site where they work—that is, most staff continue to be employed even when the M&O contract is changed. The retention of much of the enterprise workforce across actual or possible changes of their M&O contracting organization has long been recognized as crucial to the success of the mission, because of the importance of long-term, firsthand experience in the highly technical, interdisciplinary activities undertaken. NNSA’s budget in FY 2020 is $16.7 billion, and its request for FY 2021 is $19.8 billion, to support increased requirements assigned by the 2018 NPR.6

___________________

3 Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise, 2014, A New Foundation for the Nuclear Enterprise: Report of the Congressional Advisory Panel on the Governance of the Nuclear Security Enterprise, http://cdn.knoxblogs.com/atomiccity/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/12/Governance.pdf, pp. ix–x.

4 NNSA’s eight functional offices are External Affairs; General Counsel; Acquisition and Project Management; Emergency Operations; Safety, Infrastructure, and Operations; Defense Nuclear Security; Management and Budget; and Information Management and Chief Information Officer.

5 The plants and sites operated by M&O partners include Kansas City National Security Campus, Nevada National Security Site, Pantex Plant, Savannah River Site, and the Y-12 National Security Complex.

6 Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2018, Nuclear Posture Review, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF.

THE PANEL’S CHARGE

This report is the culmination of 4.5 years of work by the Panel to Track and Assess Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise. The panel was established jointly by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) in response to a congressional mandate to monitor and document DOE’s and NNSA’s response to the 2014 Augustine-Mies report. The panel was also asked to assess the effectiveness of the reform efforts and recommend what further action is needed. The congressional mandate, and the official charge to the panel, are included in Appendix A.

MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE CONCERNS AND THEIR UNDERLYING FACTORS

Over multiple decades, Congress and the defense community have been frustrated about important aspects of the nuclear security enterprise’s performance. Criticisms have included that the enterprise could not carry out major projects on budget and on schedule, and that the occurrence of safety and security incidents in the nuclear security enterprise was excessive. As a result, numerous studies and reviews of DOE and NNSA were carried out, many of them mandated by Congress. One of them, the Commission to Review the Effectiveness of the National Energy Laboratories (CRENEL), reported in September 2014 that its review of “over 50 past reports” about the DOE laboratories found “a strikingly consistent pattern of criticism with a repeating set of recommendations for improvements,”7 making it clear that the studies and recommendations, by themselves, are not effective in resolving those issues. In creating the current panel, Congress sought a mechanism that—by providing sustained attention to, and monitoring of, NNSA’s efforts to improve governance and management—would apply pressure for past recommendations to be addressed.

Studies conducted over the years have usually begun by framing the causes of poor performance of NNSA and its predecessor organizations in transactional terms. The FFRDC laboratories, for instance, have cited micromanagement by the government, excessive audits and inspections, limited span of authority to operate, and intrusive requirements for approval of decisions. The federal government, for its part, has complained about an inadequate concern in the laboratories about budgets and schedules, a lack of transparency about the work in the laboratories, an unwillingness to report “bad news” up the chain promptly, and efforts by the laboratories to go around NNSA and lobby Congress directly.

Throughout the many past studies, common concerns arose repeatedly, such as the need for “culture change,” clearer definition of roles and responsibilities, means of instilling accountability into the system, and better management and control systems for both the government and the M&O partners. Many have pointed to an overemphasis on operational formality—prioritizing compliance with rules over accomplishment of the mission—which took root in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War. Multiple issues and challenges contributed to NNSA’s persistent problems in meeting schedules, staying within cost, and maintaining safety, health, and security.

In the Augustine-Mies report, three major underlying issues were identified as factors in many of NNSA’s performance problems.

___________________

7 Commission to Review the Effectiveness of the National Energy Laboratories, 2015, Securing America’s Future: Realizing the Potential of the Department of Energy’s National Laboratories: Final Report of the Commission to Review the Effectiveness of the National Energy Laboratories, Volume 1: Executive Report, http://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/10/f27/Final%20Report%20Volume%201.pdf, p. vi.

- Competing priorities across the enterprise. Rather than having a deep commitment and sense of urgency to the accomplishment of the mission, the report expressed concern that some within NNSA were too often focused on their own specialties and offices rather than the larger mission. They were willing to tolerate delays and extra costs in order to focus on their own area of responsibility. There was not a shared alignment around the mission of the larger organization. For example, the safety czar focused on safety in isolation even if that meant the mission was delayed, rather than on how to accomplish the mission safely.

- A lack of trust between the parts of the nuclear security enterprise. This lack of trust was felt between the government and its M&O contractors, between different offices within NNSA, and between NNSA and its stakeholders at DoD and Congress. There was too little sharing of information, and parties sometimes took steps to protect themselves from blame if things could go wrong. In particular, NNSA’s laboratories were unable to fully perform their role as FFRDCs because, instead of being seen as trusted partners, they were too often viewed and treated merely as “contractors.”

- A pattern of risk avoidance in the course of pursuing the mission, rather than risk management. Instead of empowering people to take responsibility, make decisions, and be accountable, personnel sometimes sought to avoid risk through multiple layers of review, data calls, and approval requirements. A preoccupation with not making mistakes slowed progress and resulted in micromanagement and second guessing.

The Augustine-Mies panel and other groups offered their assessments of these issues and provided a number of specific recommendations to improve the situation. Those recommendations were directed at various organizations, including the Secretary of Energy, agencies within the Office of the President, and the Congress, but they most specifically went to NNSA itself.

NNSA’S RESPONSE TO THE AUGUSTINE-MIES REPORT

In the first years following the Augustine-Mies report in late 2014, which was issued when General Frank Klotz was Administrator, a number of actions were taken quickly. Among these were the creation of the Office of Cost Estimating and Program Evaluation (CEPE) in January 2015 to improve the management of major capital projects; initiation of a strategic planning process for the laboratories modeled after that of DOE’s Office of Science; and the establishment or revival of a number of boards, councils, and working groups to improve communication and coordination across the enterprise. New attention was paid to training and development for NNSA’s federal staff. The Director of NNSA’s Office of Policy took on a major leadership role, aligning the Augustine-Mies recommendations and those from other reports into “themes” and assigning responsibilities across various offices in NNSA to address them.

NNSA leadership began working to clarify roles, responsibilities, authorities, and accountability, issuing a new “NNSA Site Governance Directive” (SD 226.1B), which was published in summer 2016. The improvement in employee engagement for federal employees between 2015 and 2019 as documented in results from the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS) also is noteworthy (see Chapter 3).

In May 2019, NNSA released three strategic documents—Strategic Vision, Governance & Management Framework, and Strategic Integrated Roadmap (the latter updated in 2020)—that collectively lay out practical and valuable governance and management goals to guide the nuclear security enterprise. These documents specify shared values and expected behaviors, mission priorities, milestones, strategic management challenges, and governance and management expectations for the enterprise. They make the point that all components and levels of the enterprise have a responsibility to focus on the mission;

underscore the importance of efficient decision making; emphasize managing rather than avoiding risk; and call for clearly defined roles, responsibilities, authorities, and accountability to prevent redundancy and miscommunication. Release of these strategic documents was an important step in addressing many of the concerns identified in the Augustine-Mies report.

NNSA was responsible to Congress for developing a formal Implementation Plan for following up the recommendations of the Augustine-Mies report, which it submitted to Congress on December 30, 2016. That report documented numerous steps already taken or under way by NNSA to address specific issues identified in the Augustine-Mies report. The panel did not find this plan to be a useful tool for tracking and assessing NNSA’s progress toward its self-identified governance and management goals. In its third interim report, the panel explained why it reached that conclusion and offered suggestions for what is needed in a helpful implementation plan:

Rather than following a careful process of specifying goals and then articulating a plan to achieve them, NNSA has laid out actions it would take without linking them clearly to desired outcomes or explaining why the actions were selected. It does not consider how the various activities will interact to effect the needed changes nor does it convey how the activities will impact mission success. Of equal concern, it gives little indication of how change will be measured—there are no baselines—or how one would know that success has been attained. Furthermore, there is no plan for communicating and socializing the overall goals and progress throughout the enterprise. Such communication is necessary in order to promulgate changes, embed responsibilities for carrying out steps in the plan, and prepare for necessary adjustments to the culture across the enterprise.

An adequate plan to steer governance and management reform should include the following elements:

- A well-articulated statement of the intended concept of operations and goals (e.g., mission focus, simplicity, and clarity, as well as alignment of resources, organizations, and incentives) and what the intended result will be;

- A plan for how to achieve the goals and intended results;

- Active commitment to the goals and vision by senior-most leadership (at both NNSA and DOE);

- A plan for how to accomplish the change, including centralized leadership and decentralized implementation;

- Active involvement and engagement of personnel across the enterprise in planning and achieving the change;

- Regularly scheduled reviews of progress against predetermined measures of effectiveness—with a visible cadence and a sense of urgency—that are conveyed across the enterprise and course corrections to be made as needed to accomplish the preset goals; and

- A plan for communication and reinforcement of the desired attributes of the change through training, leadership activities, performance reviews, and ongoing continuous improvement programs.8

Hence, the panel has relied to a large extent on its own data collection and analysis in the course of this study.

___________________

8 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2019, Report 3 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., p. 32.

THE PANEL’S WORK LEADING TO THIS REPORT

Since 2016, the panel has studied NNSA’s governance and management intensively, and also examined aspects of management in other components of the nuclear security enterprise. The panel’s research and data collection methodology are described in Appendix B. The panel visited each of NNSA’s laboratories and most of its plants and sites, with multiple visits in some cases. It interviewed a large number of management personnel at different levels at the M&Os and NNSA, at both field offices and headquarters. Numerous nonmanagement employees of NNSA and its M&O partners at different levels have also been interviewed in discussion or focus groups.

In accordance with congressional direction, the panel developed written annual interim reports that were submitted to Congress and NNSA starting in early 2017, and it held midyear updates as well to apprise key congressional staff members of its data collection progress and findings throughout the study.

-

The first interim report of this panel was delivered in March 2017, a little over 2 years after the Augustine-Mies report was issued and approximately 1 year after the National Academies and NAPA were awarded their contracts for this study. One of the first themes the panel emphasized was that greater urgency should be demonstrated by NNSA in its implementation—both because of the lengthy time required for any culture change and to show staff across the enterprise that governance and management were receiving the priority they require.9

Another observation from that first report was that NNSA was not conducting the kind of analysis needed to properly rectify management inefficiencies. For example, the panel found that, although “burdensome” practices for management and oversight had been for years identified as a vexation and a sign of low levels of trust, neither NNSA nor its M&O partners had precisely characterized the term nor catalogued the problems.

-

The second interim report of this panel was released in February 2018, just as new leadership came to NNSA, with a new Administrator being confirmed by the Senate that month. Also, at about that same time, a new NPR was issued by the Administration that placed greater emphasis on the weapons modernization work of the enterprise and led to significant increases in workload, budget, and staffing. These developments brought renewed energy to the enterprise and likely contributed to a positive shift in morale and attitudes. While progress had been made in response to the Augustine-Mies concerns especially in improving NNSA’s relationships with DoD, the panel’s sense was that the response until that time had overall been limited and rather tactical.10

In light of those developments, the panel’s second report said, “NNSA is faced with an excellent opportunity—and challenge—to move from a tactical to a strategic approach for executing the critical mission of the enterprise. This report calls for NNSA to create two plans expeditiously: (1) an integrated strategic plan for the entire nuclear security enterprise, focused on mission execution, and (2) a more complete and better grounded plan to guide the ongoing

___________________

9 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2017, Report 1 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

10 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2018, Report 2 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

-

program of governance and management reform. The emphasis in both cases must be on creating a strategic vision that is clearly connected to mission.”11

New NNSA leadership and the new NPR brought increased commitment by senior leadership to culture change, increased transparency and trust, and clearer lines of authority. The new Administrator signaled her deep commitment to changing from a risk-averse, compliance-based culture by highlighting throughout the enterprise—in town halls, site visits, and other presentations—the themes of “One NNSA” (encouraging all to focus on their shared mission) and “Getting to Yes” (collaboratively solving problems so as to achieve mission progress).

-

The third interim report of this panel, issued in February 2019, remarked on many of those promising new actions. It noted, “The Administrator has taken a number of steps that appear to have placed NNSA on a promising path toward remedying the governance and management problems that have been flagged by so many reports. She has pushed energetically for partnership and mission focus throughout the enterprise, modeling healthy relationships between the government and its management and operating partners, which in turn may be reducing some transactional oversight. She has worked toward healthier relationships with the Department of Defense (DoD) and with the rest of the Department of Energy. In accordance with the panel’s 2018 recommendation for better strategic planning, she is working to improve practices in that area. It now appears that the building blocks for essential change are slowly coming together.”12

Even so, the panel still expressed concern about the lack of a documented strategic vision and accompanying strategic planning document, urgency, metrics, and institutionalization, noting that the progress to date was heavily dependent on the individuals involved. Because the governance and management reforms being pursued require a change in culture across the enterprise, which requires consistent, sustained leadership, the panel recommended that NNSA quickly appoint “a senior executive as the accountable change management leader for the next few years. The change leader should drive management and governance reform with urgency and a cadence focused on mission success.”13

-

The fourth interim report of this panel, released in February 2020, again emphasized the need for institutionalizing the promising changes in governance and management that had been promulgated. It reiterated the recommendation that “a career senior executive [be designated] as the accountable change management leader for the next several years,” and it suggested some important steps for that person to prioritize.14

In May 2019, NNSA released three strategic documents: a new Strategic Vision, Governance & Management Framework, and Strategic Integrated Roadmap for the whole enterprise. Subsequent discussions between the panel and many staff members and executives across the enterprise, from both government and M&O partners, showed widespread appreciation for the reforms spearheaded by the Administrator and for efforts at culture change.

To better understand matters affecting NNSA’s FFRDCs, during 2019 panel members also held free-ranging conversations at SNL (Albuquerque and Livermore), LANL, and LLNL,

___________________

11Report 2 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, p. 1.

12 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2019, Report 3 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 1–2.

13Report 3 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, p. 2.

14 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Academy of Public Administration, 2020, Report 4 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., p. 2.

meeting with more than 90 science and engineering (S&E) personnel to review the adequacy of the support those vital functions receive. Observations from these visits included that near-term demands and some administrative issues were stressing this work and these people, and that top leadership at the laboratories may not have been fully aware of these conditions.

During 2019, the panel observed multiple steps taken toward institutionalizing the desired governance and management changes. But at that time the panel felt that full operationalization—which requires “a multistep process of communication, codification (in some cases), and translation of general principles into guidance that is useful to the day-to-day actions of people at all levels throughout the enterprise”—was not being addressed systematically. The panel remained concerned “about the pace of progress and limited sense of urgency, the lack of metrics, and the remaining need for institutionalization. Progress is still heavily dependent on the top individuals who are pushing for change.”15

STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT

For this final report, the panel has followed the general structure of the Augustine-Mies report, beginning with a chapter on national leadership and relationships with other key governmental players, then following with chapters on NNSA’s management practices and relationships with the M&O partners, and concluding with a chapter looking to the future, on institutionalizing and monitoring change.

Appendix C presents a case study of NNSA’s plutonium pit production program, which is discussed in Chapter 3 of this report. The purpose of that case study was to examine how NNSA approaches the management of a high-priority program, given that the Augustine-Mies report had criticized some aspects of how NNSA managed projects and programs in 2014.

___________________

15Report 4 on Tracking and Assessing Governance and Management Reform in the Nuclear Security Enterprise, p. 2.